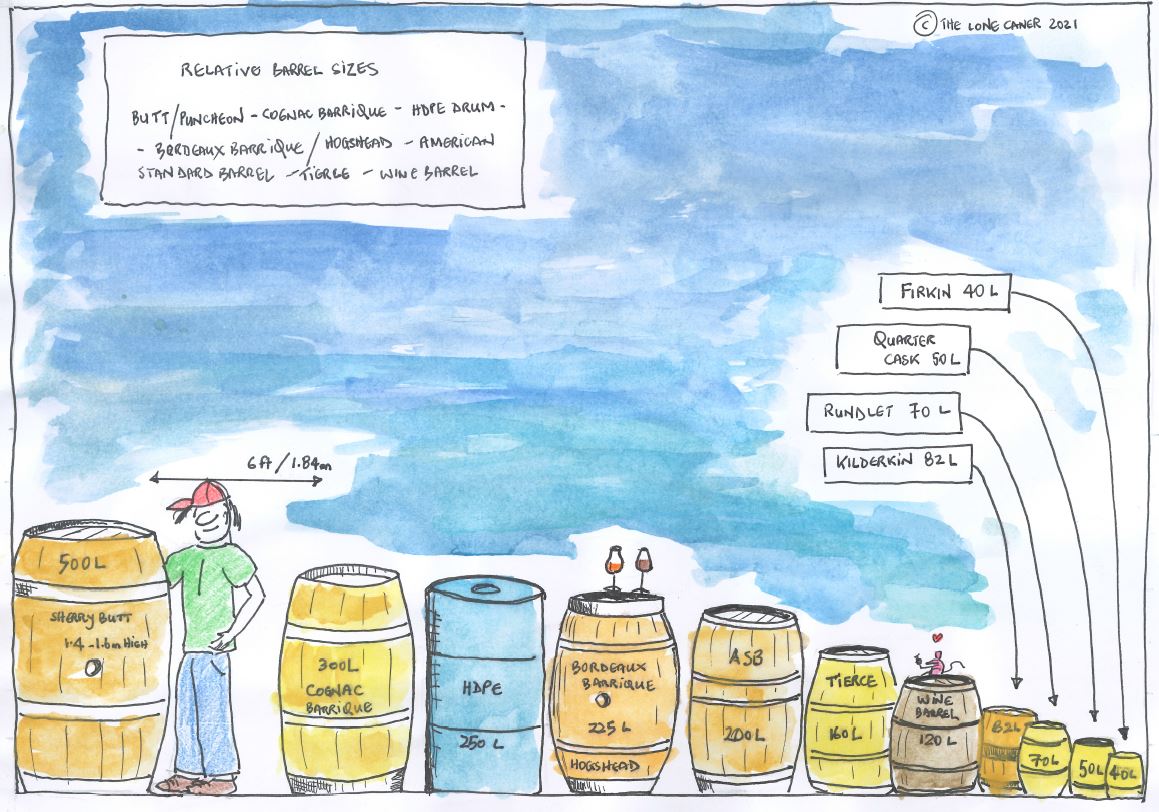

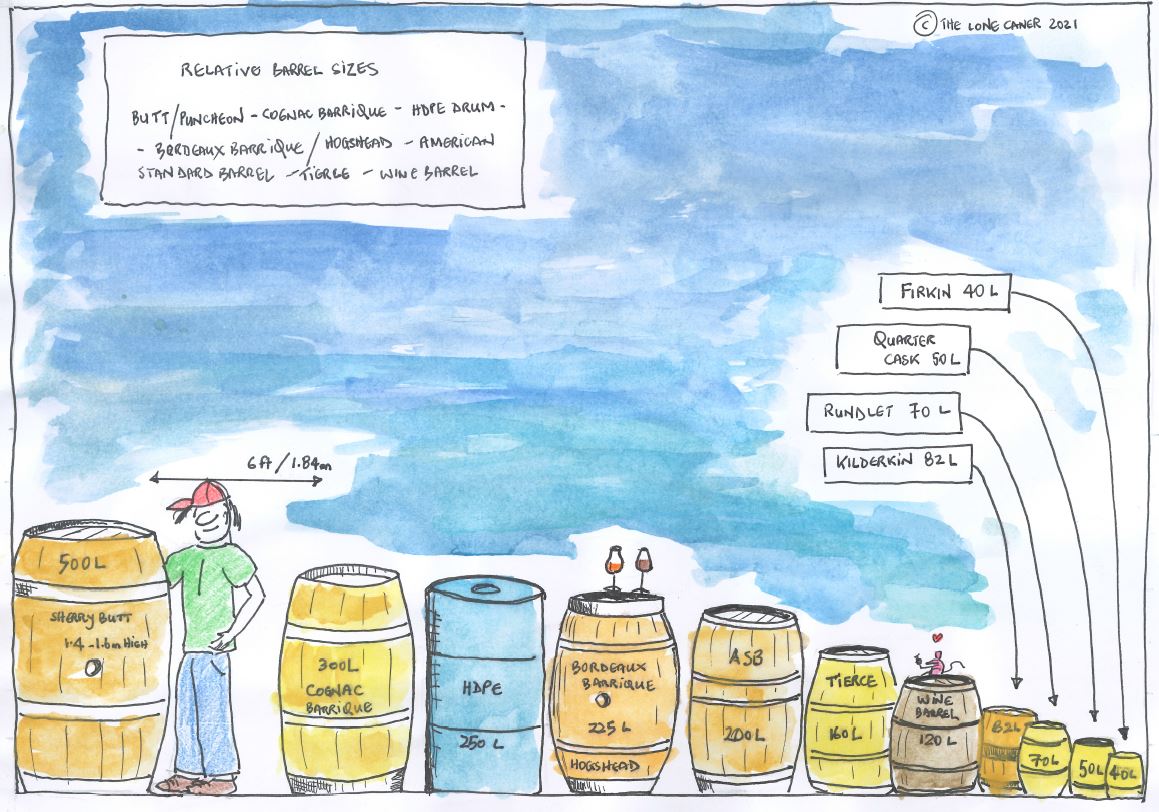

From the largest barrels (probably better called vats, at the left side)…..

Introduction

Although most of us are aware of the fact that rum, like many other spirits, is aged in barrels, it’s not always clear how large (or small) those barrels actually are, why they are called what they are, or what their original functions were. We just hear “barrels”, visualize a cylindrical container made of of wooden staves held in place by three bands, and think American oak, Limousin, French, amburana, or what have you, and move on. Occasionally we would read something like “refill barrel” or “hogshead” and if we have any more in depth queries, a trip to wikipedia or a specific site can usually clear that right up.

But I think I’m going to go a little deeper today, and examine each type of barrel in its turn, not restrict it to just rums and try and give you some more info. As with many subjects, what on the surface looks to be a fairly straightforward subject is actually rife with all the usual complexities and complications humans seem to love bringing to anything they create.

Note: barrels are used to hold and/or more than one spirit during their lifetimes, so it will not be strange to find barrels used by makers of whiskies, wines, oils or what have you in this list.

Roman transport of wine jars and barrels

General and historical

Ever since the first quantity of anything – whether solid or liquid – had to be carried or stored, mankind has invented a container for the purpose (and then a means to measure it). Primitive man used woven reeds, tree bark, then waterproof containers made of the skins or intestines of animals, then fired mud or clay.

In the early history of fermented spirits (wine), the clay amphora was the vessel used to store and transport them. Herodotus noted that ancient Mesopotamians used barrels made of palm wood for transport of wine – however, the difficulty of working with palm led to alternatives being explored, and eventually barrels constructed of staves and hoops not dissimilar to those in use today were made (since at least 2600 BC in Egypt – for measuring corn) and have been a feature of western culture for more than two millennia. Barrels made of oak came into widespread use during the time of the Roman Empire and have remained staples of the industry ever since, not just because of their convenience as storage media but because of their impact on the taste of the spirit it stored (which for centuries was wine).

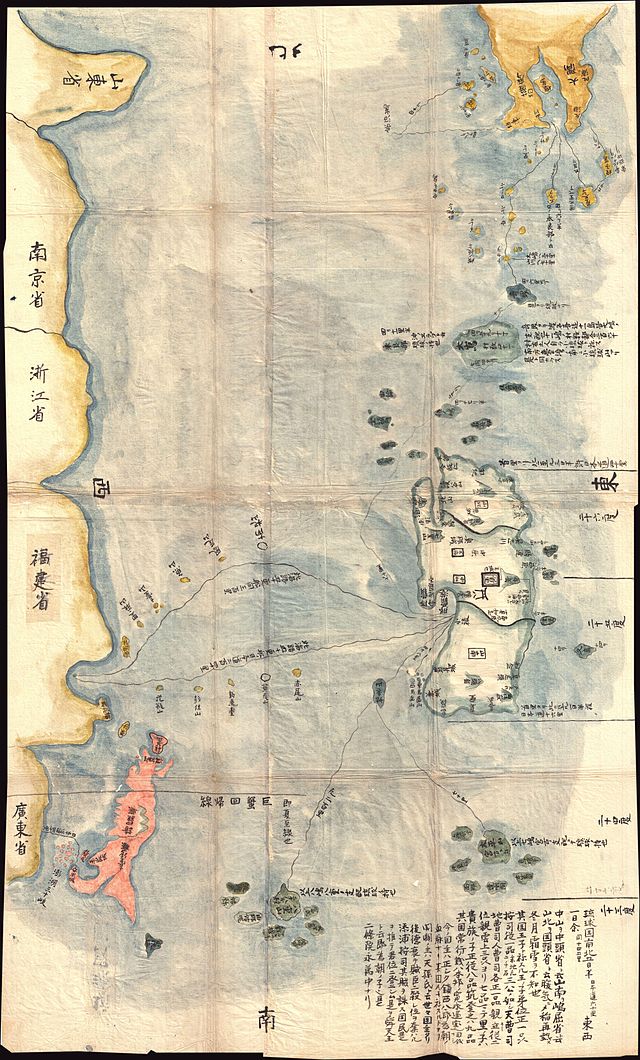

In China and the far east (including Indonesia), wines and other alcoholic spirits were often stored in earthenware or terracotta (clay) amphorae, but these were fragile and gradually replaced by wooden casks after the arrival of the European colonial powers – though not always of oak…teak was one wood widely used in Indonesia, for example.

Over the last seventy years the development of shipping containers, stainless steel vats and steel/plastic drums has rendered the wooden barrel or cask obsolete as a container for transport. However, the oak barrel’s use as an ageing medium for spirits remains completely unaffected.

The shape of a barrel is defined by two simple physical properties: the bulging middle allows them to be more easily rolled and turned whether full or empty; and the rounded construction transfers pressure well, allowing them to be stacked in a way square edged construction would not. Also, white oak is the preferred medium for spirits barrels, both because it is not as piney or resin-y as other woods (it is relatively neutral, not bitter), it is also more waterproof after treatment and transfers flavours like vanillin better, especially when charred. There’s loads more technical data around this subject – I’m just scratching the surface, really – but for now, this will suffice.

Units of measure | | |

Barrels are a very old form of container, and the further back we go, the more we diverge from the metric system: then we run into imperial and localized units of measure, differences between nations (e.g. US or UK), or the purpose of what the barrel is meant to contain, which impacts measurements down to modern times. Every culture had its measurements bases and units, often related to physical norms, such as measurements of the human body, the carrying or hauling capacity of man or animal, or the relationship of volume and weight. Unsurprisingly, standardization was a constant problem and volumetric containers like barrels were no exception.

Wine foudres

For example, a US dry barrel may be considered 115.6 liters, but also 7,056 cubic inches or 3.28 US bushels, or “exactly” 26.25 US dry-gallons (and we won’t even go into the interior and exterior measurements, lengths or thicknesses of staves, diameter of head, distance between heads, size of bulge and on and on). To add to the confusion, barrels of cornmeal, sugar, cement, flour, butter or salt are defined by weight (and different ones for each, mind you) not volume.

Fluid barrels are also different because they vary according to the particular liquid being measured…and where that’s happening (again, mostly US and UK). They can variously be measured in US gallons or imperial, be defined whether it’s containing beer, oil, or other liquids, or with reference to other supposedly “standard” sizes, like “half a hogshead” or a “euro-keg.”

For the sake of this essay I’m going to mostly stick with the western barrels and not all other containers of measure that have existed throughout history in other cultures and times. Also, I’ll refer to all measurements in liters (with notes on US/UK/other sizes), and reflect fluid barrels, not dry weight or other purposes. Lastly, barrels specific to goods like gunpowder, flour, pork or corn are excluded.

30,000-liter foudres at Saint James, Martinique (photo courtesy of Olivier Scars. from his visit and blog post),

Foudres, Muids and Tonels (1,000 liters to 30,000 liters)

The largest wooden containers which hold alcohol for ageing are foudres , which rum producers have happily co-opted from the wine makers of France. Sherry makers always thought they had the biggest and baddest barrels themselves – and although they have no standardized barrel as such, their tonel (the name can’t be a coincidence) is 800-2000 liters in capacity and therefore shares DNA with the huge foudres and muids of the wine industry, both of which also exceed 1000 liters. Some can go as high as 5000 liters, the Karukera distillery (see photo below) has one of 10,000 liters, and the Olympic champ for size must go to the 63 titanic foudres at Saint James in Martinique (left) each of which is a mind boggling 30,000 liters. And while outside the scope of discussion here, note also the use of the non-barrel-shaped Intermediate Bulk Container (IBC), which are modern, re-useable, multi-use container used for mass handling and shipping of liquids, semi-solids, and solids. These do not, however, have any application to the in situ slow, patient process of ageing which is what wooden containers are used for.

* The word foudre is, interestingly enough, not of French origin (in old French and heraldry it means “lightning” or “thunderbolt”), but from proto-Germanic and Old High German roots – it derives from “foeder” and “fuodar” which were terms used to denote a large barrel for ageing beer or wine. The word and its variations then spread throughout Europe in medieval times.

Tun (~ 950-1000 liters, Old English 252 wine gallons, two “pipes”)

Of all the wooden containers grouped under the blanket term of barrels and used in the spirits industry, the tun is one of the largest, being considered in modern times to be around one thousand liters, depending on what is being measured (though it should be observed that there are larger wooden vessels used in other spirits, noted below). It is also an extremely old word, dating back to the Old Norse and Middle Irish word tunna which denoted any cask or a barrel, and may have derived from the Old Irish tonn which meant skin, or wineskin. It was therefore a word with relationships to both volume and weight (though aspects of even older words with connotations of enclosing also exist). It was a measure of liquid volume.

The tun itself was a large vessel for storing and shipping primarily wine, honey and oil, and for measuring large volumes of beer or ale – I’m not entirely sure if it was discontinued for rum and whiskey industries, but nowadays it is considered an antiquated term for a large barrel and has faded from the common speech. It use survives in the names of containers known as the lauter tun and the mash tun, both used in the beer brewing industry

The volume-holding definition of a tun has never been strictly standardized. Nowadays, in the US customary system, the tun is defined as 252 US fluid gallons (about 954 litres), and in the imperial system, it is 210 imperial gallons (about 955 litres). The French have a similar Brobdingnagian cask called a Bordeaux tonneau, which holds 900 liters, or 1200 wine bottles, though its size can vary down to 500 liters (see picture above).

The fluid volume of a tun was somewhat settled on, when, during the early 1500s, efforts were made in England to standardize weights and measures and volumes which were often so localized as to be useless – in 1507 a tun was 240 gallons of oil or wine, but could also be 208, 240 or 256 gallons (the latter seems to have been the most common). Finally, during Henry VIII’s reign (1509-1547) a tun was fixed as the equivalent of 252 wine gallons (~954 liters), or two pipes, a number which facilitated easy division by smaller integers and which had a mass of approximately one long ton. Later, when wine gallons were redefined in 1707 as 231 cubic inches, and the imperial system was adopted in 1824, both this (210 imperial gallons) and the US system (252 US or “Queen Anne” gallons) still worked out to 954 liters. Note that in the beer industry the tun was sometimes said to have 1150 liters based on 252 imperial gallons and there are references elsewhere that say the thing holds 982 liters…so it’s not as if there is a final number to speak of here.

Gorda (700 liters, 185 US gallons, 154 Imperial gallons)

This huge barrel has fallen out of favour in the Scotch whisky industry, since its capacity is close to the maximum permitted barrel size of 700 liters. It is closely identified with American whiskey which continues to utilize it on a limited basis, usually for blending purposes.

Nowadays it is not common — being nearly three times the size of an American Standard Barrel, it’s simply too large (the name itself is Spanish for “fat”), and this creates problems for short term ageing (less surface area contact with the liquid). Also, it is difficult to char properly with existing equipment, problematic to move easily, and even more difficult rack in a warehouse given their weight when filled. That said, the large capacity makes it useful for producing blended, vatted whiskies.

Again, the sherry industry has a cask shorter and fatter than the 600 liter bota gorda (fat cask), called a bocoy. This is usually around 700 liters capacity, and is therefore similar to the 700-800 liter tonelete, a small tonel.

Leaguer (~680 liters / 150 imperial gallons (varies))

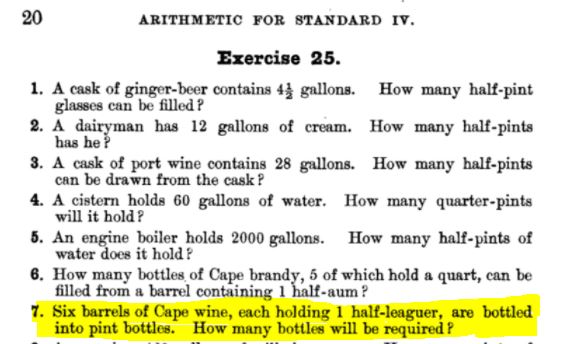

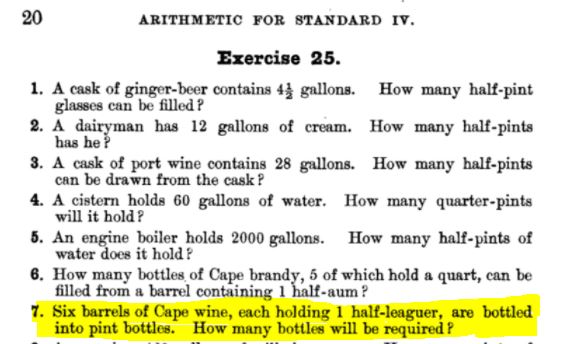

A leaguer is another large cask, but seems to have less connection to the British spirits industry and more of the storage of water on board sailing ships and Dutch measurement systems from the 1700s. An archaic word, it has faded from common usage and can only be found in a few nautical references, many of which contradict each other.

For example, wikipedia has no direct entry for it but mentions that a 33-foot launch from 1804 (a launch was the largest boat carried by a warship or merchantman in the age of sail) could carry 14 leaguers of 680 liters each; Nelson’s body was supposedly preserved in a leaguer (filled with brandy, not rum); the wordnik page calls it (erroneously, in my view) a tun, and states it as being 159 gallons without attribution, though this might come from the OED (shorter edition); the Society of Nautical Research has various sources in the conversation that define it as 250 gallons, 159 gallons or 190 wine gallons of water. Note that a leaguer was generally agreed by all modern sources to be outside of the subdivided tun-butt-puncheon-hogshead-tierce-barrel system.

That said, its origin is from the old Dutch word legger, part of the now-obsolete 17th century Dutch and South African measurement of capacity for wine and spirits which was finally abandoned in 1922. In this system, fluid measurements were related to the standard kanne (a can) of 11/32 Dutch gallons (1.329 liters), which was defined in Amsterdam. 388 kannes or 152 Dutch gallons were equal to 1 legger (~576 liters, roughly analogous to a butt, referred to below). Further subdivisions of a legger were as follows:

Legger → half legger → pipe → half-pipe → ahm (or aum) → half aum → anker → half anker → flask → kanne.

These varied sizes of barrels were used most often in Dutch shipping for their fluid or dry stores. However, given that no current barrel or system of volume uses the word, this section is included for completeness only; to avoid further confusion and for the sake of brevity, here’s the reference you can look up if you want more.

Pipe barrel – note the narrower profile [Photo (c) oak-barrel.com]

(650 liters / 171.7 US gallons / 143 Imperial gallons)

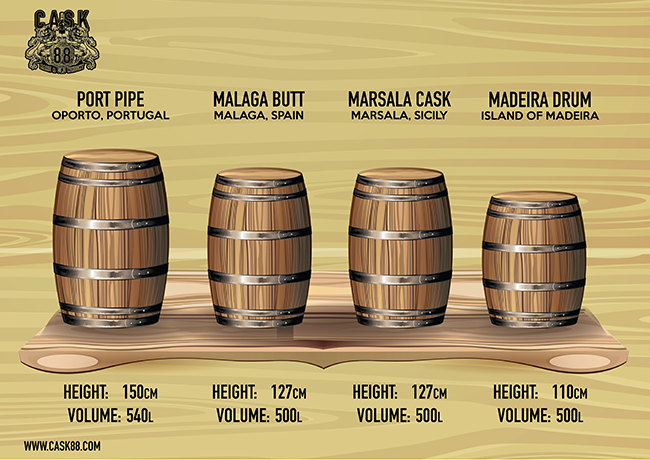

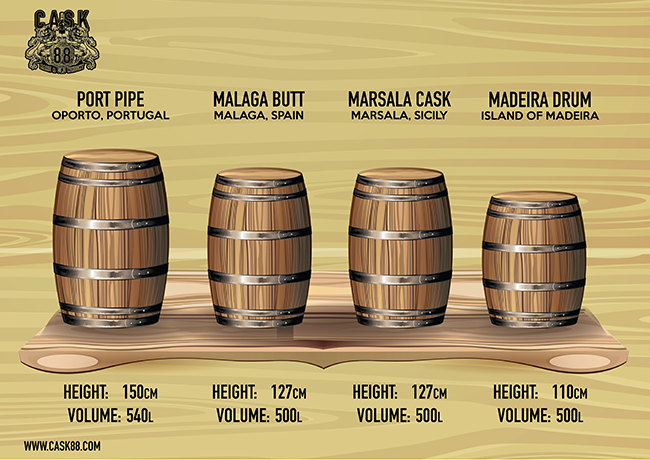

Compared to their chubby and squat Madeira cousins, Port Pipes more resemble giant American Standard Barrels (ASBs). The word pipe in this instance refers not the smoker’s implement but to the Portuguese word pipa, meaning “cask”, such as were once used to mature port; it’s something of a coincidence, perhaps, that the shape is slightly more cylindrical, longer (or taller) and narrower than a standard barrel. The size varies with some sources noting them as 540 liters capacity, while others mentioning 650 liters.

As the name implies, they are used to mature Port wines. They are then quite often sold on and utilized as “second use” barrels in whisky distilleries, and more recently, in an occasional rum making establishment. More recently, American craft distillers have taken a liking to them in helping expand American whiskey’s flavors, along side Madeira, Malaga and Marsala barrels (see below)

Madeira Drum (up to 650 liters / 171.7 Imperial gallons / 143 US gallons)

Squat Madeira casks, called drums, are made using very thick European / French oak staves and are shaped rather wider, and shorter than other barrels. In the whiskey industry they are most often used as a finishing cask, and less frequently for primary maturation. Note however that madeira casks (of any kind) are sometimes much less than the 650 liters noted in the title and can range from 225 liters to 300 liters, or even 500 liters according to another source.

Demi-Muid (600 liters / 132 Imperial gallons / 158.5 US gallons)

These large-capacity oak barrels are typically used in the Rhône Valley in France in the wine industry, but have no application or use in spirits as far as I am aware. Weighing in at 124 kg (264 lbs) they are about four feet (117cm) high, with eight metal hoops. Most wineries prefer to use the more manageable puncheons, but demi-muids are still made. The sherry equivalent is a bota gorda, also 600 liters.

The full size muid is a barrel-type with a volume of 1,300 liters, most common in the Châteauneuf-du-Pape area, while the smaller demi-muid (half size version) is common in Champagne and Languedoc-Roussillon. A muid is sometimes equated to a poinçon (puncheon) or is one of the possible types of barrique barrels (see below).

…to the smaller and more common variations. Heights are as close to scale as I could make them

Butts

In medieval French and Italian, the botte (Spanish had the word bota) was considered to be half of a tun, or 1,008 pints and referred to the same barrel as a pipe (above). They may have been equivalent at one time, but modern usage of the terms makes the distinction in between the larger capacity pipe and the slightly less voluminous butt, which is more or less standardized at 500 liters (though not consistently so)

Sherry Butt (500 liters / 132 gallons / 110 imperial gallons)

These tall casks are built with thicker staves, and are the most common type of cask in the sherry industry, and also the most common finishing cask in the whiskey industry. The demand for Sherry butts in the Scotch industry in particular is so great that a whole Sherry butt industry has grown up to support it, seasoning the casks with a Sherry style wine that is usually distilled into brandy rather than bottled as the real product. It is sometimes called a bota de extraccion / embarque which translates as “export butt.” Similar to the bota bodeguera with a capacity of 567 liters

Malaga Butt (500 liters)

The Malaga butt is from Spain as is clear from the name; with this barrel some noticeable lengthening similar to a Marsala cask starts to take place culminating in the port pipe (see above). It’s a relatively tall and narrow cask from Europe, utilizing thicker than normal ok staves. It is commonly used in the sherry industry in Spain and again, also within the whisky industry as a finishing barrel.

Illustration (c) Cask88.com

Marsala Cask (500 liters / 132 gallons / 110 imperial gallons)

As the name states this comes from the Marsala region of the island of Sicily where they are used to store and age dry or sweet fortified wine of that name. Fortified Marsala was, and is, made using a process called in perpetuum, similar to the solera system used to produce sherry and some rums. The Marsala casks can and are used for the whisky finishing process (not so much primary maturation) and due to the sweet dark type of wine, whiskies that mature in these casks are usually somewhat darker than normal. (Additional info on Sicilian wines is presented in this interesting article).

Puncheons

A puncheon rum was originally a high-proof, heavy-type rum said to have been first produced in Trinidad, at Caroni, in 1627, but that was probably only because of the barrel it was stored in: the term itself is far older, dating back to early medieval times (~13th century) when it denoted either an instrument to make a hole or a mark (like a punch in gold or silver jewelry) or to the old French ponchon or poinçon– a barrel of a certain volume and value, marked with a stamp. It was therefore occasionally referred to as a “punch barrel” to mean it had been calibrated by punching marks into it after an inspection.

UK/US puncheons

Historically the puncheon was a British unit for beer, wines and spirits, and an American one for the capacity of a barrel of that name holding wine. However, it has been subject to some variations. In the UK it has been at one time or another 318-546 liters (70-120 imperial gallons) while the Americans defined it as 318 liters (84 US gallons and 4/3 of a Hogshead (see below)). The RumLab’s infographic that notes it as 450 liters exactly, is therefore somewhat imprecise. Note that a puncheon was also referred to as a tertian or tercian (see below) because at one time it was in fact ⅓ of a tun, at around 330 liters. Nowadays they have a rather greater capacity than that, ranging from 500-700 liters depending on what it is used to mature – sherry puncheons are supposedly larger than those used for rums.

Machine Puncheon (500 liters / 132 US gallons / 110 Imperial gallons)

This is a short and fat cask made with thick staves of American oak and according to various sources is the one used most by the rum industry. It shares a similar capacity with the Sherry Shape Puncheon (also 500 liters), but that one has a different shape – thinner and longer staves are used here, making it more akin to a pipe.

A 500L tonneau and a 250L barrique

Barrique (Cognac) (300 liters / 79 US gallons / 66 Imperial gallons)

The word barrique is a very old one and although long in use in English, itself comes from even older words in Gaul (baril), vulgar latin (barrica) and old French / Occitan (barrica) all of which relate to wooden casks used for storage.

Barriques are relatively small casks used most often to age or store wines, cognac and grappa, and are often toasted to enhance flavour profiles. They come in two types, and this is the larger version, used mostly in the wine and cognac industry and then subsequently in the whisky world as second-hand casks for finishing purposes. It is slightly more elongated than a butt and close to a hogshead in capacity and in place of metal hoops binding the staves together, is distinguished by the traditional use of wooden ones. As far as I am aware, few rum makers use them given their access to alternatives.

Note also that a cognac cask, as this is sometimes referred to, can have a capacity of 350 liters. It depends on the cooperage, the size desired by the maison, and to some extent local tradition.

HDPE Drums (250 liters / 55 Imperial gallons / 65 US gallons)

Almost exclusively for transport and storage of bulk spirits and oils, the high density polyethylene containers are considered inert and food safe, and are therefore useful to ship large quantities of neutral spirit around the world for blenders or third party bottlers to turn into gins, vodkas or other (even cheaper) drinks. They have no place in the traditions of maturation which makes sense since they do not interact with the liquid inside.

Hogshead (225-250 liters / 59-66 US gallons / 49-54 Imperial gallons)

Surely there is no more evocative name for a barrel than this one, yet the etymology is uncertain. The words “hogge’s” and “hed” are demonstrably what they mean today, but the connection with the cask and a pig’s head remains unclear – some say it’s a resemblance thing. It dates back from the Germanic languages in the late medieval period (~14th century) and referred to a measure of capacity equivalent to 240 liters (63 wine gallons, 52½ imperial gallons, or specifically half a pipe, half a butt or a quarter of a tun) – it was standardized by an Act of Parliament in 1423, though it continued to vary geographically elsewhere, as well as depending on the liquid inside. Now a unit of liquid measurement, originally it could refer to any appropriately sized container holding tobacco, beer, wine, ale, cider, sugar, molasses, sardines, oil, herring, or even eels. Within the spirits industry the 225-liter hogshead made of white American oak is primarily used for maturing bourbon before being sent elsewhere to be used in the rum and scotch whisky industries.

It is the practice in the whisky industry to break down five ex-bourbon “standard” barrels (ASB, see below) into staves and to reassemble them with new ends to make four larger 250 liter casks called “hoggies” as the larger casks are more efficient to store volumes of spirits in warehouses.

Also, in the sherry industry, there is a 250 liter barrel called a media bota, which is half the size of the regular bota.

225L wine barrel, or barrique

Barrique (Bordeaux) (225 liters / 59 US gallons / 49 Imperial gallons)

A second type of barrique exists, used predominantly in the wine industry, specifically Bordeaux in France, where the measurement of 225 liters was fixed by law in 1866. Before that, the size varied according to the region and could be anything between 136 and 400 liters. It is slightly smaller than the 300-liter cognac version, but retains the traditional wooden hoops, and the secondary use as a whisky finishing barrel. There are also Burgundy barriques, which are closely sized at 228 liters.

The size and popularity of these Bordeaux-sized barrels supposedly derived from their ease of use: one man could roll a barrique around, and only two people were needed to load one. Note that the word barrique is simply French for “cask.” It is further subdivided into a feuillette of just about half this size (110 liters) and a quarteau half again as small and sometimes called a “quarter-barrique” (55 liters).

American Standard Barrel, 200L

American Standard Barrel (200 liters / 53 US gallons / 44 Imperial gallons / ⅕ tun )

No matter how many other sizes of barrel there are, the most common current barrel in use is the American one, whose size is denoted as the “American Standard Barrel” or “Bourbon barrel” and is sometimes noted as being just a smaller hogshead, without the cool name. The reason behind its ubiquity is the US law that requires most American whiskeys to be aged in new oak barrels – consequently, after a single use they are useless there, which creates a massive surplus. The barrels are exported – often by breaking them down into staves and then reassembling them into hogsheads elsewhere – for reuse in maturing other spirit types including rum, tequila, tabasco pepper sauce, and of course Scotch and Irish whiskies. This makes the ASB the most commonly used barrel in the world. Unsurprisingly, American distillers think these casks provide the optimum surface-area ratio for maturing spirits.

Note that its origin in America means it is not directly related or numerically tied to the imperial system of the English wine cask sizings of tun-pipe-puncheon-hogshead-tierce-barrel-rundlet. The origins of both are, however, undoubtedly the same and just adjusted for customary local usage. There are references to the capacity being 50-53 US gallons (180-200 liters) but most places I checked and people I spoke to maintain that 200 liters / 53 US gallons is the standard.

Tierce (158-160 liters / 35 Imperial gallons / 42 US gallons)

The word itself is of antique Roman (latin) and old French origin, and means “the third” or “a third”. The tierce was ½ of a puncheon, ⅓ of a butt or pipe, and ⅙ of a tun – when the now-archaic imperial system was instituted in the 15th century the tun was redefined to make it easily divisible by other integers and smaller barrel sizes. Its primary purpose was for wine transport, rum maturation and the storage of salted goods like fish or pork. It is almost exactly the same as a British Brewery Barrel (160 liters but also denoted as 288 pints or 43 gallons) or the Beer Barrel (140 liters, 35 imperial gallons, 42 US gallons) which in turn was used mostly in the storage of beer, ale or lager. This subsystem of liquid measurement had its own peculiarities of barrel sizes and names, like the kilderkin and the firkin (see below)

Most entries on the tierce refer to its relationship to the oil barrel. The oil boom in Pennsylvania in the 1860s created a shortage of containers (let alone standardized ones), so any barrel of whatever shape or size was used, including the 40 US gallon whiskey barrels and the 42 US gallon tierces, the former of which was far more common, and available. In 1866, to counter ever-increasing buyer distrust about measures, oil producers came together and settled on the whisky barrel as the standard barrel of measure and added an allowance of two extra gallons “in favour of the buyer”. This made a standard oil barrel 42 US gallons, the same capacity as the tierce from the time of Richard III of England.

Octave (unclear – 125 liters or 50 liters)

The Whisky Exchange’s blog made reference to an Octave barrel, naming it a quarter the size of a butt, or around 125 liters, which was considered small enough to allow for faster maturation but large enough to permit that maturation to be slower and take longer. Clearly the name refers to it being ⅛ of a tun. That said, the Whisky.com page on cask sizes states that the octave was ⅛ of a butt, or 50 liters but since the very same article also notes that a butt is 500 liters or so, then their math isn’t quite right since one eight of that amount is actually 62.5 liters. WhiskyIntelligence also mentions that it’s 50 liters, ⅛ of a “standard cask” except that there is no standard cask of 400 liters, so again, something of a puzzle. AD Rattray’s “Octave Project” also refers to it as 50 liters (no further qualifications). Let’s agree that it’s one eighth of something, whether a tun or a butt.

Wine Barrel (~120 liters / 26 Imperial gallons / 31.5 US gallons)

Not utilized in the spirits industry as far as I am aware, this barrel remains in use by wine makers and is the equivalent of ½ a wine hogshead or ⅛ of a tun. It therefore shares both the general size and the relative obscurity of an octave. This particular type of barrel is likely the same as the small French wine cask called a feuillette (110 liters). I have no doubt that the wine industry has similar subgradings and fractions of large containers being called other names as the barrel size decreases, but that is peculiar to wine and not the primary focus here, so I’ll simply note it, and pass on.

Kilderkin (81.83 liters / 18 Imperial gallons / 21.62 US gallons)

A kilderkin is half a british Brewery Barrel and conforms to British brewery measuring systems (not those of wine which then became those of distilled spirits). It is mentioned here for completeness, but is not in use for the spirits industry in any consistent or meaningful way. Note that over time there were several differing measurements for this medium sized barrel – initially it was 16 ale or beer gallons (73.94 liters) but was redefined in 1688 to 17 gallons, and again in 1803 to its current size of 18 imperial gallons of ale or beer.

The various ratios are: 1 Beer (or British Brewery) barrel = 2 kilderkins = 4 firkins. For the geek squad, note that the word is from the Middle English and this in turn from the Middle Dutch words kinderkin a variant of kindekijn (small cask), and a diminutive of kintal (i.e., “little kintal”) which is a corruption of the Latin word quintale. It has old French and even Arabic roots, stretching back through Byzantine Greek and into the Latin word centenarium (hard “c”) which referred to a hundred pounds, later a hundredweight. It is possible that a barrel of such capacity filled with wine, ale or beer weighed this much, but I was unable to prove that and so the reason why it was named a quintale remains unknown.

Photo (c) fanaticscountryattic.com

Rundlet (68-70 liters / 15 Imperial gallons / 18.1 US gallons)

Part of the wine measurement system also used by distilleries, a rundlet is 1/7 of a butt and 1/14 of a tun, which makes those parent barrels’ odd sizings and capacities – chosen for easy subdivision – make rather more sense. A rundlet is another one of those archaic barrel sizes once common in Britain, and was originally defined as about 18 wine gallons and then in 1824 (the date of adoption of the imperial system) settled on 15 imperial gallons

Traditionally for the transport of wine, the cask size has now fallen into disuse and has more interest from a historical perspective than anything else. The word comes from old Middle English and Anglo-Norman words “rondelet” and “rondel” (with connotations of a round shape, no doubt.)

The name has passed into the company of equally archaic and seldom-used colloquialism like “quent” and means any small barrel of no certain dimensions which may contain anywhere from 3 to 20 gallons.

Quarter Cask (50 liters / 11 Imperial gallons / 13 US gallons)

A quarter cask is exactly what its name says it is, a cask one quarter of the size of another one – in this case, the American Standard barrel – and made in exact proportion. Its attraction, of course, is in providing a much greater surface area to liquid ratio, thereby making the maturation process more rapid. However, it is mostly used by smaller brewers and distillers or even those practising from home. It’s sometimes confused with a firkin (see below) but the two barrels are quite distinct types and sizes – the quarter cask one has its origin in the US spirits business, while the firkin (and kilderkin) both come from European beer and ale brewing traditions. Both, however, are a quarter the size of their “parent” barrel.

Firkin (41 liters / 9 Imperial gallons / 11 US gallons)

As noted , the firkin has its origin in the brewing industry, though differing shapes of it were also used for dry goods storage (sugar, flour, peas, etc): it is ½ the size of a kilderkin, and a ¼ of British Brewery Barrel (sometimes called ale or beer barrels), and is occasionally but misleadingly referred to as a quarter cask because it is a quarter the size of the standard brewing barrel of 160 liters. Here I make a clear distinction between the firkin and the American quarter cask because of its different size and origin. The firkin’s use in spirits predates the micro-distillery and DIY brewing boom in the US, and has been used for a long time by Scottish distilleries to speed up cask-spirit interaction, as well as to sell more affordable quantities of spirits to private buyers (as was noted in the origin story of the SMWS, for example).

But as stated, its origin was with brewing and storage of ale and beer and to this day a firkin of 9 imperial gallons, or 72 pints is used to deliver cask conditioned beer to publicans (pubs), though the volume of consumable beer within it is usually less. It is not always shaped like a barrel, but sometimes like a bucket, which makes sense given its use for storage and transport by an individual.

But as stated, its origin was with brewing and storage of ale and beer and to this day a firkin of 9 imperial gallons, or 72 pints is used to deliver cask conditioned beer to publicans (pubs), though the volume of consumable beer within it is usually less. It is not always shaped like a barrel, but sometimes like a bucket, which makes sense given its use for storage and transport by an individual.

As to the origin of the word: it comes from the same source as the kilderkin, namely Middle Dutch vierdekijn, meaning “little Fourth.”

Blood Barrel / Blood Tub (40 liters / 9 Imperial gallons / 11 US gallons)

A small barrel used in beer making, but also for moving spirits on horses or mules. It therefore has no ageing usage, just for transport and small scale sales to private individuals, such as in private casks. They sport a somewhat more elongated oval shape to facilitate carriage and fastening. The exact reason it’s called a “blood” barrel is unknown – it may be because it was used to capture blood from slaughtered animals for use in sausages or some such (my surmise).

Pin (20 liters / 4.5 Imperial gallons / 5.4 US gallons)

Used by home brewers or by microbrewers, this small container is ½ of a firkin (see above). There is no point to ageing anything in a cask so small and reactive where it made of wood, so it’s mostly a storage medium, and plastic variations of this size – known as “polypins” are popular for homebrewing and small deliveries, as well as in beer festivals.

There are also minipins of around 10 liters which are used to serve ale in people’s homes in the UK. Half the size of a pin, they are usually filled by decanting from any larger container like a pin or a firkin.

Barracoon / barrack (4 liters / 0.9 Imperial gallons / 1 US gallon)

At the very bottom end of the scale is the barracoon, which is perhaps more decorative than functional and displays a peculiar insensitivity for word useage, since the word itself actually means a pen or cage used to keep slaves awaiting shipment during the slave trade. I can find no reference to this tiny cask in a dictionary, or in online encyclopedias. Diffords mentions it without any narrative whatsoever, and ASW Distillery out of Georgia in the US gives it a quick mention without context. Neither describe what it could be used for, though it seems clear that it could only be for some kind of personal use, since it is far too small for any kind of serious commercial application.

15.3 gallon Stainless Steel Keg

Kegs

Kegs are a kind of small barrel insofar as the shape is the same, and like barrels, have their own subculture and nomenclature. The term is not in common usage for the rum (or spirits) industry, but everyone is familiar with it from quaffing suds.

Traditionally, a keg made of wood was simply a small barrel of indeterminate size – it was used to transport solid goods like nails or gunpowder or corn, or liquids like oil and wine. Its use therefore tended more towards the private than the commercial. Nowadays a keg is often made of metal (stainless steel), very much associated with beer, and has a stated purpose of keeping a carbonated beverage under pressure to keep it from going flat.

That said, it remains curiously non-standardized: where the capacity might be the same, the linear measurements might differ, and vice versa. However, in the USA a full sized keg is seen as a half barrel, or 15.5 US gallons, a quarter-barrel of 7.75 gallons or some subdivision thereof. The key to this is that it doesn’t refer to any of the barrels I have listed above (like the ASB), but a US beer barrel, which is listed as 31 US gallons (about 117 liters).

Of course, beer kegs can come in any kind of size and the accepted convention that they are smaller than a barrel is about all that can be said for them. They can range from 5 liters (1.32 US gallons) for a mini-keg or “Bubba”, to 19 liters (5 US gallons) for a “Corny keg” or “Home Brew” then in ever increasing volumes to a half barrel, a pony keg, an import keg (also known as a “standard European” keg of 50 liters) and then finally the Full Keg of 15.5 US gallons as noted in the paragraph above. Of course there are other variations and sizes and names, but these are the common ones.

A subset of this is the so-called Euro-keg of a commonly accepted capacity of 50 liters. There are smaller subdivisions of this size in Germany (which with a complete Teutonic lack of imagination names them DIN 6647-1 and DIN 6647-2 for example) and the UK denominates its keg size as 11 imperial gallons, which happily works out to 50.007 liters. But in an interesting aside, in some places within Germany where a pour is half a liter, a keg’s capacity is measured in beers, not liters, so that’s pretty cool.

Vats

A vat is any large volume barrel, and is a general catch-all term, not one that is rigorously defined in any official system of weights and measures. It therefore is in the same league as the French foudre and muid, or a tub or a tank, also large-volume containers without clear volumetric definitions. Because of the size, such vessels are at the other end of the scale from kegs or pins.

It is also a very old word, dating back to the Proto-indo-European prefix “pod-” (or vessel) – a word itself at the root of pot. It developed into proto-Germanic “fata” (again, for a vessel or container) and a similar meaning in the Old English “fæt”, though I think it’s similarity to water and wasser suggests a water storage vessel as well. From there it moved into Medieval English and was gradually turned into “fat” meaning a vessel or tank and was used to describe large container used for tanning hides and wine making, with cognates all over the northern European world.

These days, due to its lack of definition and lots of other alternatives, the word is very general in nature. Its use in spirits is retained in calling tanks “vats” especially when producing “vatted whiskies” or naming blended rums like Vat 19.

Intermediate Bulk Containers (wikipedia)

Intermediate Bulk Containers (IBCs)(1040 or 1250 liters / 228 or 275 Imperial gallons / 275 or 330 US gallons)

Not used for ageing, they are akin to the HDPE drums mentioned briefly above. They are multi-purpose industrial-grade, intermediately-sized and mostly cube-shaped shipping containers, easy to stack or store; and used for the transport and storage of liquids, semi-solids and solids. Their popularity stems from a combination of storage efficiency (they fit into less space than equivalent volume barrels), utility and flexibility since they can be of many shapes and sizes, and of metal, plastic or a composite and are often manufactured to exacting (Government- or industry-mandated) standards permitting transport of hazardous materials.

IBCs come in two varieties, rigid and flexible. Rigid ones are made of plastic, composite, carbon steel or stainless steel, while flexible IBC can be made from fiberboard, wood, aluminium, plastic, and often are seen as heavy sacks. Oak does not fit into their makeup anywhere.

20′ ISO Bulk Shipping Container – 26,000 Liters

Unsurprisingly rum (and other spirits) are not normally stored in these containers, since they are inert and have no impact on the profile. They are not part of any systems of weights and measures outside the logistics industry. Nor do they have any tradition in the back-history of rum, the distilleries, plantations, or the shipping trade – they are, in point of fact, a modern innovation like the standardized shipping container and are used in modern transport mechanisms. So, for bulk transport and/or storage of alcohol, whether on site or in a vessel, they have their uses and I include them here for completeness.

ISO Bulk Shipping containers with a capacity of thousands of liters are also quite common for distilleries which ship spirits around the world. The 20′ Tank Shipping Container mentioned in this article, for example, has a capacity of 26,000 liters. As rum is now shipped globally in massive quantities by huge distillery operations, doing so via the space-inefficient means of wooden barrels clearly is a non starter.

Trivia

An article like this leads down many obscure rabbit holes that are at tangents to the main purpose. I collect them because I’m a trivia nut and because some of them are just so damned interesting.

- Someone who makes barrels is called a “barrel maker” or cooper. However, coopers make many different kinds of enclosed containers, including not just the familiar terms above (hogsheads, firkins, kegs, kilderkins, tierces, rundlets, puncheons, pipes, tuns, butts and pins) but buckets, vats, tubs, butter churns, troughs and breakers.

- The term barrel to refer to the shooting tube of a cannon (and later, a gun) is directly related to the barrels discussed above. Early metallurgical technology was not sufficiently advanced to contain the explosive force of gunpowder combustion without the tube down which the cannonball would go, warping or exploding. This tube, or pipe, which was sometimes made from staves of metal, needed to be periodically braced with hoops along its length for structural reinforcement – this produced an appearance somewhat reminiscent of storage barrels being stacked together, hence in English it adopted the term of barrel.

- I said above that a leaguer is an archaic term for a water barrel on board ship in the Age of Sail, though references to such barrels holding wine also exist. One of the most peculiar is a page from the 1907 “Clive’s South African Arithmetic for Standard IV” which had a question requiring the student to convert a half-leaguer to pints.

Other

I have excluded non standardized storage media like tanks, casks (oddly, this is not a defined unit or container of measure or storage, though of course everyone knows what one is), reservoirs, containers, pots, flasks, tubs, drums, or cans. There’s a fair bit of information about these things, but they have limited applicability to spirits generally and rum specifically.

Sources

- 1882, James Edwin Thorold Rogers, A History of Agriculture and Prices in England, p. 205: Again, by 28 Hen. VIII, cap. 14, it is re-enacted that the tun of wine should contain 252 gallons, a butt of Malmsey 126 gallons, a pipe 126 gallons, a tercian or puncheon 84 gallons, a hogshead 63 gallons, a tierce 41 gallons, a barrel 31.5 gallons, a rundlet 18.5 gallons.

- Handy Conversion webpage

- Other websites’s articles on barrels. I’m not the only one with a post dedicated to barrels. Most of the others are from the whisky boys, and here are a few that cover the same territory:

Neisson L’Esprit Blanc, Martinique – 70%

Neisson L’Esprit Blanc, Martinique – 70% Jack Iron Grenada Overproof, Grenada – 70%

Jack Iron Grenada Overproof, Grenada – 70% L’Esprit Diamond 2005 11 YO, Guyana/France – 71.4%

L’Esprit Diamond 2005 11 YO, Guyana/France – 71.4% Takamaka Bay White Overproof, Seychelles – 72%

Takamaka Bay White Overproof, Seychelles – 72% Plantation Original Dark Overproof 73 %.

Plantation Original Dark Overproof 73 %.

Longueteau Genesis, Guadeloupe – 73.51%

Longueteau Genesis, Guadeloupe – 73.51% SMWS R3.5 “Marmite XO”, Barbados/Scotland – 74.8%

SMWS R3.5 “Marmite XO”, Barbados/Scotland – 74.8% Forres Park Puncheon White Overproof, Trinidad – 75%

Forres Park Puncheon White Overproof, Trinidad – 75% SMWS R3.4 “Makes You Strong Like a Lion” Barbados/Scotland – 75.3%

SMWS R3.4 “Makes You Strong Like a Lion” Barbados/Scotland – 75.3%

Inner Circle Cask Strength 5 YO Rum (Australia) – 75.9%

Inner Circle Cask Strength 5 YO Rum (Australia) – 75.9%

SMWS R5.1 Long Pond 9 Year Old “Mint Humbugs”, Jamaica/Scotland – 81.3%

SMWS R5.1 Long Pond 9 Year Old “Mint Humbugs”, Jamaica/Scotland – 81.3% L’Esprit South Pacific Distillery 2018 Unaged White – 83%

L’Esprit South Pacific Distillery 2018 Unaged White – 83% Sunset Very Strong, St. Vincent – 84.5%

Sunset Very Strong, St. Vincent – 84.5% L’Esprit Diamond 2018 Unaged White – 85%

L’Esprit Diamond 2018 Unaged White – 85% Romdeluxe “Wild Tiger” 2018, Jamaica/Denmark – 85.2%

Romdeluxe “Wild Tiger” 2018, Jamaica/Denmark – 85.2% Marienburg 90, Suriname – 90%

Marienburg 90, Suriname – 90%

DOK – Trelawny Jamaica Rum – Aficionados x Fine Drams – 69% / 85.76%

DOK – Trelawny Jamaica Rum – Aficionados x Fine Drams – 69% / 85.76%

Plantation Extreme No. 4 Jamaica (Clarendon) 35 YO 74.8%

Plantation Extreme No. 4 Jamaica (Clarendon) 35 YO 74.8% Dillon Brut de Colonne Rhum Blanc Agricole 71.3%

Dillon Brut de Colonne Rhum Blanc Agricole 71.3% Velier Caroni 1982 Heavy 23 YO (1982 – 2005) 77.3% | Caroni 1985 Heavy 20 YO (1985 – 2005) 75.5% | Caroni 1996 Heavy 20 YO (1996-2016)(Cask R3721) Legend” 70.8% | Caroni 1996 Heavy 20 YO (1996-2016)(Cask R3718) Legend” 70.8% | Caroni 1996 “Trilogy” Heavy (1996 – 2016) 70.28%

Velier Caroni 1982 Heavy 23 YO (1982 – 2005) 77.3% | Caroni 1985 Heavy 20 YO (1985 – 2005) 75.5% | Caroni 1996 Heavy 20 YO (1996-2016)(Cask R3721) Legend” 70.8% | Caroni 1996 Heavy 20 YO (1996-2016)(Cask R3718) Legend” 70.8% | Caroni 1996 “Trilogy” Heavy (1996 – 2016) 70.28% Cadenhead Single Cask Black Rock WIRR 1986-1998 12 YO 73.4%

Cadenhead Single Cask Black Rock WIRR 1986-1998 12 YO 73.4%

Rom Deluxe Jamaicans (Hampden) – R.17 “Rhino” 5th Anniversary Edition 2019-2021 <2 YO 86.2% | R.20 “Springbok” (C<>H) 2020-2022 86% | R.23 “Pronghorn” (C<>H) 2020-2021 < 2YO 86% |

Rom Deluxe Jamaicans (Hampden) – R.17 “Rhino” 5th Anniversary Edition 2019-2021 <2 YO 86.2% | R.20 “Springbok” (C<>H) 2020-2022 86% | R.23 “Pronghorn” (C<>H) 2020-2021 < 2YO 86% |

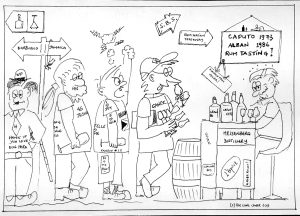

The “ancillary sessions” I refer to above are almost always seminars and masterclasses and if you’re wondering, a seminar is an informative get together for anyone who’s interested with maybe a tasting tacked on, while a masterclass is exactly what it describes. This is why when Richard Seale goes into the technical details of the endochronic properties of resublimated thiotimoline it’s a masterclass (and usually leads to a thundering stampede for the exits five minutes in), while a run-through of six agricole rhums by a distributor is closer to a seminar.

The “ancillary sessions” I refer to above are almost always seminars and masterclasses and if you’re wondering, a seminar is an informative get together for anyone who’s interested with maybe a tasting tacked on, while a masterclass is exactly what it describes. This is why when Richard Seale goes into the technical details of the endochronic properties of resublimated thiotimoline it’s a masterclass (and usually leads to a thundering stampede for the exits five minutes in), while a run-through of six agricole rhums by a distributor is closer to a seminar.

Thirdly, as noted above, unless you’re okay with simply wandering around, talking to people and randomly stopping wherever it suits you, it is a good idea to know which

Thirdly, as noted above, unless you’re okay with simply wandering around, talking to people and randomly stopping wherever it suits you, it is a good idea to know which

Once at the festival itself, one of the most important things to always keep in mind is that you will be there for a few hours at the very least (my personal record is seven) and be tasting a lot of rums, very quickly. Palate fatigue is a real thing, and so is intoxication, both of which derail the experience. Therefore, take it easy, take your time, and most of all, take small sips, and nose more than taste.

Once at the festival itself, one of the most important things to always keep in mind is that you will be there for a few hours at the very least (my personal record is seven) and be tasting a lot of rums, very quickly. Palate fatigue is a real thing, and so is intoxication, both of which derail the experience. Therefore, take it easy, take your time, and most of all, take small sips, and nose more than taste.

The Rum Barrel Blog

The Rum Barrel Blog The Rums of the Man With the Stroller

The Rums of the Man With the Stroller Who Rhum the World?

Who Rhum the World?

Rum Gallery

Rum Gallery

Atlas Du Rhum (Luca Gargano)

Atlas Du Rhum (Luca Gargano) The Silent Ones (Cyril Weglarz)

The Silent Ones (Cyril Weglarz) Rum Curious (Fred Minnick)

Rum Curious (Fred Minnick)

But as stated, its origin was with brewing and storage of ale and beer and to this day a firkin of 9 imperial gallons, or 72 pints is used to deliver cask conditioned beer to publicans (pubs), though the volume of consumable beer within it is usually less. It is not always shaped like a barrel, but sometimes like a bucket, which makes sense given its use for storage and transport by an individual.

But as stated, its origin was with brewing and storage of ale and beer and to this day a firkin of 9 imperial gallons, or 72 pints is used to deliver cask conditioned beer to publicans (pubs), though the volume of consumable beer within it is usually less. It is not always shaped like a barrel, but sometimes like a bucket, which makes sense given its use for storage and transport by an individual.

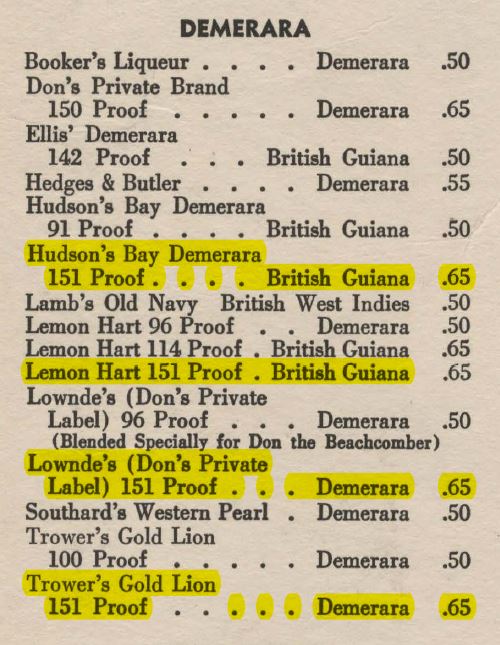

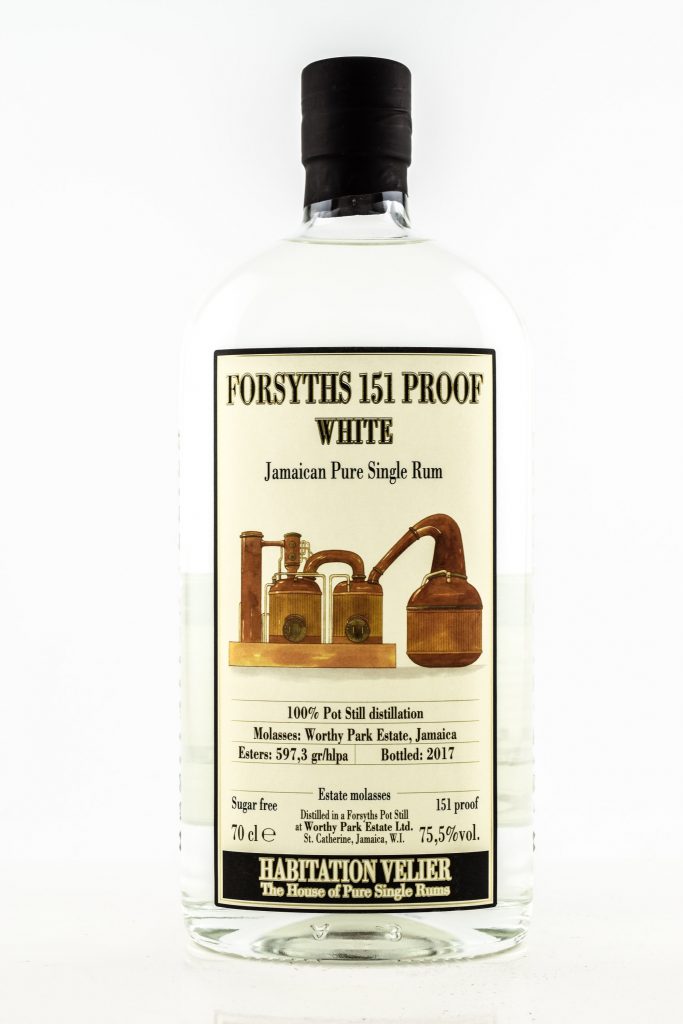

Others are less interesting, or less specific and may just exist, as many had before, to round out the portfolio – Don Q from Puerto Rico makes a 151 to this day, and

Others are less interesting, or less specific and may just exist, as many had before, to round out the portfolio – Don Q from Puerto Rico makes a 151 to this day, and

Martinique – Saint James pot still white rum (60%)

Martinique – Saint James pot still white rum (60%) Guyana – El Dorado 3 Year Old white rum (40%)

Guyana – El Dorado 3 Year Old white rum (40%) Guyana-Italy

Guyana-Italy Thailand – Issan (40%).

Thailand – Issan (40%). Guadeloupe – Longueteau Rhum Blanc Agricole 62°

Guadeloupe – Longueteau Rhum Blanc Agricole 62° Mexico – ParanubesWhite Rum (54%).

Mexico – ParanubesWhite Rum (54%). Madeira-Italy – Rum Nation Ilha da Madeira (50%)

Madeira-Italy – Rum Nation Ilha da Madeira (50%) Madeira-UK – Boutique-y Reizinho White Agricole (49.7%).

Madeira-UK – Boutique-y Reizinho White Agricole (49.7%). Martinique – HSE Rhum Blanc Agricole 2016 (Parecellaire #1)(55%)

Martinique – HSE Rhum Blanc Agricole 2016 (Parecellaire #1)(55%) Reunion-Italy – Habitation Velier HERR.

Reunion-Italy – Habitation Velier HERR. Cabo Verde – Vulcao Grogue White (45%)

Cabo Verde – Vulcao Grogue White (45%) Haiti-Italy – Clairin Le Rocher (2017)(46.5%)

Haiti-Italy – Clairin Le Rocher (2017)(46.5%) South Africa – Mhoba White Rum (58%)

South Africa – Mhoba White Rum (58%) Liberia – Sangar White (40%).

Liberia – Sangar White (40%). Cabo Verde – Musica e Grogue White (44%)

Cabo Verde – Musica e Grogue White (44%) Japan – Helios “Kiyomi” White Rum (40%)

Japan – Helios “Kiyomi” White Rum (40%) French Antilles – Rhum Island “Agricultural” (50%).

French Antilles – Rhum Island “Agricultural” (50%). Viet Nam – Sampan White Overproof (54%).

Viet Nam – Sampan White Overproof (54%). Laos – Laodi Sugar Cane White Rhum (56%).

Laos – Laodi Sugar Cane White Rhum (56%). Cabo Verde – Barbosa Grogue Pure Single Rum (45%).

Cabo Verde – Barbosa Grogue Pure Single Rum (45%).

When the Scandinavians started publishing their results, the roof blew off — it quite literally changed the rum landscape overnight. For the first time there was proof — clear, testable, incontrovertible

When the Scandinavians started publishing their results, the roof blew off — it quite literally changed the rum landscape overnight. For the first time there was proof — clear, testable, incontrovertible  The El Dorado 15 remains a staple of the rum drinking world to this day in spite of its now well-publicized dosage. It has received much opprobrium for the lack of disclosure (DDL never commented on the matter of dosage until an interview with Shaun Caleb in 2020, and for the record the practice is being phased out) and has slipped somewhat in people’s estimation to being a second tier aged product. Yet it remains enormously popular and is a perennial best seller, a rum many new entrants to the field refer to as a touchstone, even though DDL has moved to colonize the space Velier pioneered and begun issuing cask strength limited bottlings from the stills themselves in 2016 (the

The El Dorado 15 remains a staple of the rum drinking world to this day in spite of its now well-publicized dosage. It has received much opprobrium for the lack of disclosure (DDL never commented on the matter of dosage until an interview with Shaun Caleb in 2020, and for the record the practice is being phased out) and has slipped somewhat in people’s estimation to being a second tier aged product. Yet it remains enormously popular and is a perennial best seller, a rum many new entrants to the field refer to as a touchstone, even though DDL has moved to colonize the space Velier pioneered and begun issuing cask strength limited bottlings from the stills themselves in 2016 (the