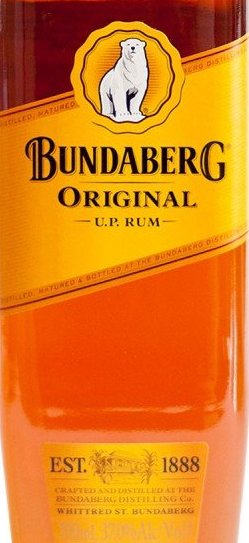

For years, Bundaberg was considered the Australian rum, synonymous with the country, emblematic of its distilling ethos, loved and hated in equal measure for its peculiar and offbeat profile (including by Australians). Yet in 2022 its star has lost some twinkle, it rarely comes up in conversation outside Queensland (where it sells like crazy), and another distillery has emerged to take the laurels of the international scene – Beenleigh.

Scouring through my previous notes about Beenleigh (see historical section below), it seems that even though VOK Beverages got a controlling interest in the enterprise back in 2003, they contented themselves with providing bulk rum to Europe (beginning with distillates from 2006 shipped in 2007) and servicing the local market. They were clearly paying some attention to market trends, however, because slowly their international recognition got bigger as indies began releasing Beenleigh rum under their own labels to pretty good reviews, and you could just imagine the glee of Wayne Stewart, Beenleigh’s acclaimed Master Blender (he’s been in that position since 1980, some 41 years, which is pretty much as long as Joy Spence over in Appleton), who knew how good his juice was and finally saw it get some well deserved recognition. Bringing in an engaging, technically astute, social-media savvy gent like Steve Magarry onboard as Distillery Production Manager didn’t hurt at all either.

And yet, as of this writing, almost the only rums from Beenleigh that are widely seen, are those from the independents like SBS, Rum Artesanal, TCRL, Velier, Valinch & Mallet, L’Esprit and others. Beenleigh itself is not well represented outside Australia yet, either in the EU or in North America (perhaps because they’re too focused on chasing down Bundaberg in the young-aged volume segment, who knows?) In that sense it’s a pity that the one Beenleigh rum in the 2021 Australian Advent calendar I managed to obtain, was one of their weakest — not the five or ten year old, not the barrel aged or port-barrel-infused, which are all at standard strength or a bit stronger…but the three year old white underproof bottled at 37.5%, which is part of the standard lineup.

The website provides a plethora of information about the product: molasses based, 3-4 days’ fermentation, pot-column still blend, matured in (variously) kauri (local pine) vats and brandy vats for the requisite three years before being undergoing carbon filtration. The product specs state 0% dosage, and I’ve been told it has some flavourant, just a bit, which is slated to be eliminated in years to come. Then it’s all diluted slowly down from ~78% ABV to 37.5% — which means you get a very smooth and light sipping rum that doesn’t hurt, or a relatively quiet cocktail ingredient that doesn’t overpower. It’s like an Australian version of the Plantation 3 Star, a similarly anonymous product that some people have an obscure love affair with and prefer for precisely those attributes.

The website provides a plethora of information about the product: molasses based, 3-4 days’ fermentation, pot-column still blend, matured in (variously) kauri (local pine) vats and brandy vats for the requisite three years before being undergoing carbon filtration. The product specs state 0% dosage, and I’ve been told it has some flavourant, just a bit, which is slated to be eliminated in years to come. Then it’s all diluted slowly down from ~78% ABV to 37.5% — which means you get a very smooth and light sipping rum that doesn’t hurt, or a relatively quiet cocktail ingredient that doesn’t overpower. It’s like an Australian version of the Plantation 3 Star, a similarly anonymous product that some people have an obscure love affair with and prefer for precisely those attributes.

This is a rum that is light enough that letting it stand for a few minutes to open in a covered glass is almost a requirement. A deep sniff reveals a very sugar cane forward scent, redolent of sweet and delicate flowers, vanilla, sugar water and a sort of mixture of tinned sweet corn and peas, a touch of lemon peel and more than a hint of nail polish, acetone and glue. Going back a half hour later and I can sense a raspberry or two, some bubble gum and a bare hint of caramel and molasses but beyond that, not anything I can point to as a measure of its distinctiveness. Even the alcohol is barely discernible.

It is thin, sweet and piquant to taste, smooth as expected (which in this context means very little alcohol bite), with initial notes of white guavas, unripe green pears, figs, green peas (!!), ginnips, and again, some lemon peel and vanilla. A bit of toffee, some molasses lurk in the background, but stay there throughout. It really doesn’t present much to the taster’s buds or even as a challenge, largely because of the low ABV. It is sweet though, and that does make it go down easy, with a short, light finish that presents some red grapefruit, grapes, unripe pears and a mint chocolate.

Overall, this is not a rum that I personally go for, since my own preference is for stronger rums with more clearly defined tastes; and as I’m not a cocktail expert or a regular mixer (for which this rum is explicitly made), the rum doesn’t do much for me in that department either…but it will for other people who like an easygoing hot weather sipper and dial into those coordinates more than I do. The rum succeeds, as far as that goes, quietly and in its own way, because it does have a touch of bite — an edge, if you will, perhaps imparted by those old, old heritage local kauri pine vats — that stops it from simply being some milquetoast yawn-through tossed off to populate the low end of the portfolio. It’s a drowsing tabby with a hint of claws, good for any piss up or barbie you care to attend…as long as you’re not asking anything too special.

(#877)(76/100) ⭐⭐½

Historical Notes

Beenleigh, located on the east coast of Australia just south of Brisbane, holds the arguable distinction of being the country’s oldest registered distillery (the implication of course being that a whole raft of well known but unregistered moonshineries existed way before that). The land was bought in 1865 by two Englishmen who wanted to grow cotton, since prices were high with the end of the US civil war and the abolition of slavery that powered the cotton growing southern states. Company legend has it that sugar proved to be more lucrative than cotton and so this was in fact what was planted. In 1883 the S.S. Walrus, a floating sugar mill (which had a distilling license, granted in 1869 and withdrawn in 1872) that plied the Logan and Albert rivers and processed the cane of local landowners, washed ashore at Beenleigh, empty except for the illicit pot still on board, which was purchased by Beenleigh – they obtained a distilling license the very next year.

Through various vicissitudes such as boom and bust in sugar prices, floods that washed away distillery and rum stock, technological advances and many changes in ownership, the distillery doggedly continued operating, with only occasional closures. It upgraded its equipment, installed large vats of local (“kauri”) pine and organized railway shipments to bring molasses from other areas. In 1936 the distillery was described as having its own wharf, power plant, a cooper’s shop and all necessary facilities to make it a self-contained producer of rum. Some have been replaced or let go over time but the original pot still, called “The Old Copper”, remains in a red structure affectionately named “The Big Red Shed”) and is a prized possession.

Beenleigh’s modern history can almost be seen as a constant fight to survive against the more professionally managed Bundaberg distillery up the road (they are 365km north of Brisbane). Bundie has had far fewer changes in ownership, is part of the international spirits conglomerate Diageo, has a much larger portfolio of products and its marketing is second to none (as its recognition factor). Much of that continuity of tradition and expertise by owners is missing in Beenleigh, as is a truly long term strategic outlook for where the rum market is heading – it can’t always and only be about low-cost, low-aged, low-priced rums that sell in high volumes with minimal margins. That provides cash flow, but stifles the innovation into the higher-proofed premium market segment which the indies colonize so well. Beenleigh could probably take a look at Foursquare to see how one distillery with some vision could have the best of all worlds – bulks sales, low cost volume drivers, and high-priced premium limited editions, all at the same time. It’ll be interesting to see where this all goes, in the years to come.

Other notes

- A very special shout out and tip of the trilby to Mr. And Mrs. Rum of Australia (by way of Mauritius). The Australian advent calendar they created in 2021 was unavailable for purchase outside of Oz, but when they heard of my interest, they sent me a complete set free of charge. After years of grumbling about how impossible it was to get to review any rums from Down Under, the reviews deriving from those samples will fill a huge gap on the site. Thanks again to you both.

Rumaniacs Review R-159 | #1036

Rumaniacs Review R-159 | #1036

As for the taste when sipped, “uninspiring” might be the kindest word to apply. It’s so light as to be nonexistent, and just seemed so…

As for the taste when sipped, “uninspiring” might be the kindest word to apply. It’s so light as to be nonexistent, and just seemed so…

Colour – Light Gold

Colour – Light Gold

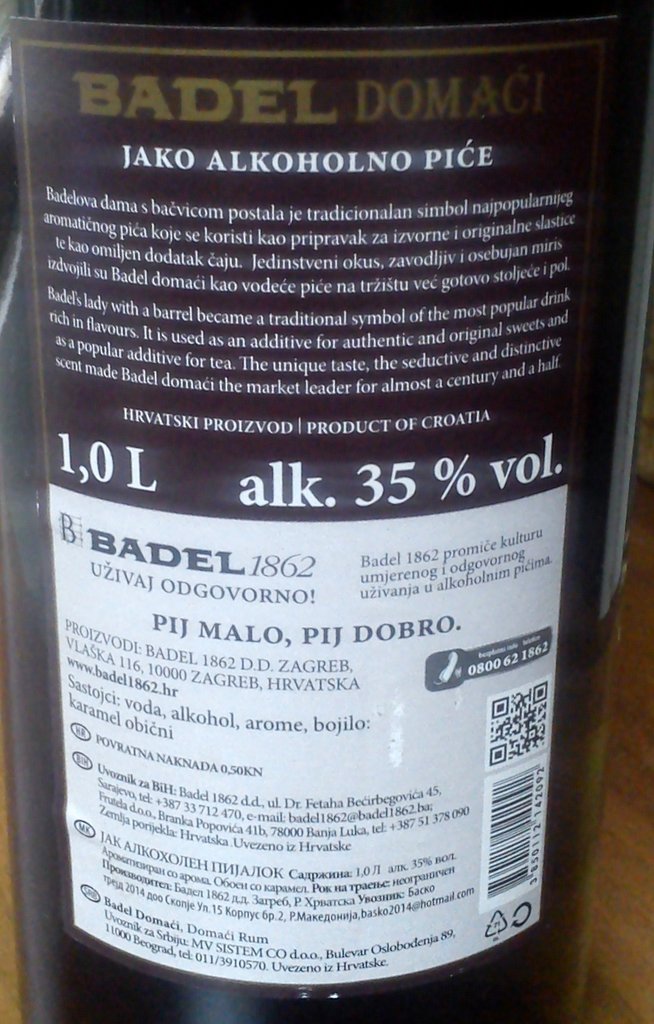

Unsurprisingly it’s mostly for sale in the Balkans — Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia, with outliers in Germany — and has made exactly zero impact on the greater rum drinking public in the West. Wes briefly touched on it with a review of

Unsurprisingly it’s mostly for sale in the Balkans — Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia, with outliers in Germany — and has made exactly zero impact on the greater rum drinking public in the West. Wes briefly touched on it with a review of