There are many Indian spirits combines on the subcontinent which make rum — Radico Khaitan, Mohan Meakin and United Spirits, are some examples — not all of which are well known by rum folks elsewhere because of their predilection for selling domestically, or only in Asia. Still others concentrate on beer, whisky or various other industrial manufacturing enterprises, and the rum component of their sales is so minor that it is not widely exported. And yet rum is one of the oldest distilled spirits made in India, and it is this which founded the fortunes of Amrut Distilleries way before they started finding global fame as purveyors of that obscure Scottish drink in the 2010s.

What became Amrut Distilleries – the name means “nectar of the gods” in Sanskrit1 – was established in 1939 in the south-central-Indian city of Bangalore as Associated Drugs Co. Ltd, and then in 1947 as Amrut Laboratories — the founder, JN Radhakrishna Rao Jagdale, was a chemist — with an investment of a few hundred thousand rupees. At the time its stated purpose was over the counter drugs and pharmaceuticals (particularly cough syrup) but with the gaining of independence, opportunities for local Indians expanded in concert with the relaxation of licensing laws. This allowed a distillery licence to become easier to acquire, so Mr. Jagdale promptly got one, and Amrut Distilleries was registered in 1948 (the pharmaceutical division was retained).

If one were to read the various online newspapers, magazines and hagiographies of Amrut, one could be forgiven for concluding that it jumped fully formed out of Zeus’s brow in the 1980s when they first began making malted whiskey, leading to the global successes and acclaim of their single malts in the 2010s. However, like most Indian producers of spirits, Amrut had a history before that, and it is frustrating in the extreme to find almost nothing written about the company that would give a more detailed picture of what it did between 1950 and 1982.

(c) Amrut Distilleries

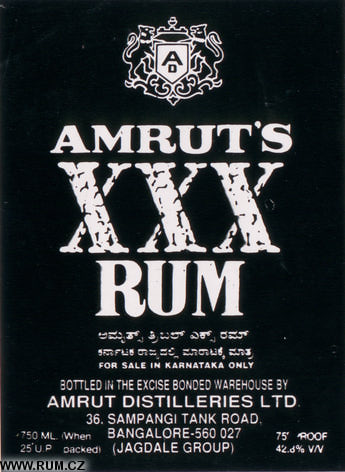

Be that as it may, Amrut by 1949 had already begun making a blended brandy called “Silver Cup” and debuted in the state of Karnataka (of which Bangalore is the capital and largest city) – vinyards were spreading around Bangalore at that time, so there was a ready supply of grapes (though there was, as was common at the time, a fair bit of adulteration going on…see next paragraph). This must have sold well enough to keep the business afloat, but strangely enough, even with the example of Dyer Meakin’s Solan No.1 whiskey, Amrut did not immediately branch out into whiskies, but for several years mostly sold brandies and rums. Some attention was obviously being paid, however, since by 1962 the company had a contract with the army, (probably following on the example set by Dyer Meakin’s very successful Old Monk rum from 1954) — and they supplied brandy, Amrut XXX rum and Prestige XXX whiskey to the armed forces’ 3000 or so canteens. To this day, sales to the armed forces remain a significant proportion of the companies’ revenues.

It should be pointed out that during these decades, local spirits – “Indian Made Indian Liquors” or IMIL, and locally manufactured foreign ones “Indian Made Foreign Liquor” or IMFL – catered primarily to the low-end mass-market of India. Brandies were from local grapes, rums from local molasses, and gins and whiskies were often from distillate that also came from molasses — in the latter case, with 10%-15% of malted whisky thrown in to make the taste more “genuine”. In many cases, neutral alcohol was mixed with some of the real spirit or additives to give the impression of genuine-ness, and then watered down to below the maximum allowable strength (45% or so).

It should be pointed out that during these decades, local spirits – “Indian Made Indian Liquors” or IMIL, and locally manufactured foreign ones “Indian Made Foreign Liquor” or IMFL – catered primarily to the low-end mass-market of India. Brandies were from local grapes, rums from local molasses, and gins and whiskies were often from distillate that also came from molasses — in the latter case, with 10%-15% of malted whisky thrown in to make the taste more “genuine”. In many cases, neutral alcohol was mixed with some of the real spirit or additives to give the impression of genuine-ness, and then watered down to below the maximum allowable strength (45% or so).

This was more than just rank pecuniary opportunism, mind (although there was plenty of that too): part of the reason for this procedure in whiskies was that in a country plagued by food shortages and even famines, it was problematic to use grain for the manufacture of alcohol. And alcohol itself was a touchy moral subject when considered with poverty and alcohol’s ambivalent reputation (some states do not allow alcohol to be sold on payday, as an interesting aside). The adulteration and dodgy manufacturing might have allowed costs to be kept miniscule and prices low for local consumers, but was the major reason no Indian whisky was permitted to call itself Scotch or Scots whisky in the EEC and EU for a very long time, in spite of their seeming pedigree and occasional names deriving from Scots culture.

With these facts in mind it would seem logical (in the absence of better information to the contrary) to assume that Amrut essentially played a long and slow game of gradual expansion. They started with brandy, moved into rum and then did a blended whisky which was based at least partly on molasses distillate, as all distillers were doing at the time. Much of the research available suggests that the Bangalore facility was and has remained the main operational centre and initially comprised of a liquor blending and bottling unit, with a distillery added at some later point in the 1950s.

By 1972 they were distilling their own brandy so clearly they had moved away from just blending, and gradually, if slowly, expanding beyond the borders of Karnataka. In that same year, the 19-year-old Neelakanta Rao Jagdale joined the company (the exact position he was given is unclear, though most sources agree he was helping his father “run” the company). This was fortuitous timing, as four years later in 1976, Radhakrishna Rao Jagdale, the founder of the company, died, and Neelakanta stepped up to become Chairman and Managing Director. The company forged on under Neelakanta’s leadership, however, and it could be argued that his achievements and the direction he gave Amrut in the 1980s made it a seminal decade in the company’s early history.

In 1984, a Government monopoly over spirits was instituted in the southwestern state of Kerala via the Kerala State Beverages Corporation, and Amrut was licensed to sell to them, thereby acquiring a large market share in that state; they similarly expanded into other states in this decade, and gained loyal customers in states like Pondicherry, Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh and Delhi in addition to its own state of Karnataka. This was accompanied in 1987 by an expansion and refurbishment of the Bangalore distillery, with additional distillation equipment brought in to increase capacity as restrictions on imports were eased.

In 1984, a Government monopoly over spirits was instituted in the southwestern state of Kerala via the Kerala State Beverages Corporation, and Amrut was licensed to sell to them, thereby acquiring a large market share in that state; they similarly expanded into other states in this decade, and gained loyal customers in states like Pondicherry, Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh and Delhi in addition to its own state of Karnataka. This was accompanied in 1987 by an expansion and refurbishment of the Bangalore distillery, with additional distillation equipment brought in to increase capacity as restrictions on imports were eased.

Amrut also broke new ground in taking aim at a more premium segment of the Indian spirits industry, when the deregulatory wave of Thatcherite and Reaganite economics started to sweep around the world. In 1982 they began to experiment with making whisky, not just as an inferior and cheaply made mix of real and neutral and molasses spirit, but from grains. This did not stop the MaQintosh whisky from being made as an initially cheap blend, though perhaps it was more notable for casually appropriating two evocative terms – the Mac computer and a Scottish name – than any intrinsic quality of its own. It was followed in 1986 by the Prestige Blended Malt Whisky, which was also blended with flavourings while at the same time reducing the quantity of molasses spirit and focusing much more on barley. Yet all the while the company was starting to work towards making a true Single Malt.

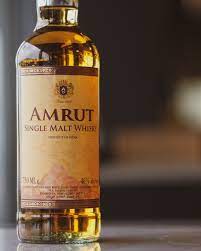

By the mid 1990s they had developed whisky that was all from Indian grain and aged to the standard required by international regulations, and Jagdale felt it was of a quality that matched Scottish 12 year old whiskies. The problem was, although they had burgeoning stocks, enough to sell, could they make enough of it to go on and scale up, and could they sell it outside of India? Other companies were also making malted whisky with malted barley imported from abroad (because of grain shortages in India), and this restricted Amrut’s plans…until the early 2000s.

(c) Amrut Distilleries

Several events intersected at that point. For one, India became self sufficient in grain for the first time and so more was available for alcohol manufacture. Secondly, industrial technology infrastructure got a boost with the ethanol plants built by Praj Industries in the late 1990s so grain alcohol became seen as an economically viable substitute for molasses-based rectified spirit, or extra neutral alcohol. As deregulation gathered steam and a new and more sophisticated (and affluent) urban middle class emerged in India, the moral taboos and restrictions on grain based spirits began to recede. And lastly, there was the impetus and competition given to local spirits companies and their IMFL by the entrance to the Indian market of foreign liquor multinationals who had the benefit of larger supplies and that air of long-established authenticity which Indian made liquors did not have.

The entry of global spirits conglomerates was crucial because it invaded the premium section of the market, the same one local companies like Amrut were aiming to colonise themselves. Amrut knew that they could either go the route of building strong, original, authentic brands that could compete in the top end — and globally — or be relegated to the mass market, where they would be tied to a multitude of (complex, bureaucratic and often corrupt) local state government agencies and razor thin margins. Vijay Mallya’s United Spirits group solved this issue by acquiring foreign alcohol businesses with well known brand portfolios, saving them the trouble of building their own, but Amrut went in the opposite direction: they would compete directly and build their own brands, reasoning that there would be a knock-on effect for all their other products.

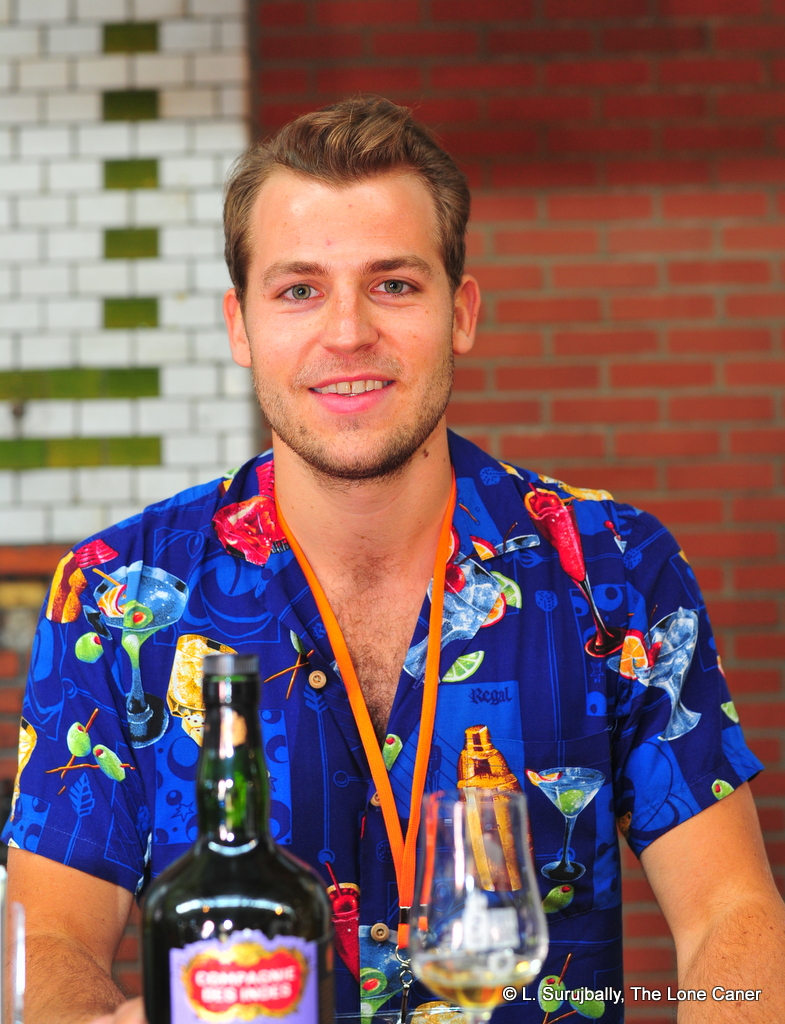

The story has been told so many times that it has been raised to the status of company myth. In 2002 Neelakanta’s son Rakshit was studying for an MBA in Newcastle-on-Tyne in northern England and his father gave him the task of exploring the potential of Amrut’s single malt whisky. Rakshit, with his fellow MBA classmate and friend Ashok Chokalingam, did a series of blind tastings in restaurants and bars, starting with a neighbourhood Indian establishment and eschewing jaded connoisseurs’ opinions in favour of the regular whisky drinkers who would consume the same preferred drink consistently. The results were mostly positive and so he expanded into Scotland and traditional pubs, where again there was approval. This in turn allowed Rakshit to build up a network of suppliers and distributors, and in 2004 — after two years of coming up to scratch on the EU’s packaging standards — the Amrut Single Malt whisky debuted in Britain (in the Cafe India in Glasgow, for trivia-enthusiasts), with expansion to Europe in 2005 (in an odd twist, Amrut’s single malts only became available in India in 2010).

The logic of introducing an Indian single malt in Britain and the EU was sound: Neelakanta knew that a foreign stamp of approval would raise awareness and sales in India in a way that sidestepped and shortcut the much longer process of winning over local customers, had the whisky first been released domestically (this is a cultural block that afflicts many home-grown spirits, not just whisky and not just in India). That said, initial sales, while decent, were modest, climbing from 2000 cases at first, to 5000 cases in 2008. The tipping point came in 2010 when Jim Murray named the Amrut Fusion released the previous year as the third best whisky in the world. After over a decade of experimentation, marketing, slogging and anonymous legwork, Amrut became an overnight success, if not an outright sensation and, as Neelakanta had predicted, local sales exploded. By 2019 global sales of malt whisky were close to 70,000 cases, in dozens of countries (and that number has surely increased).

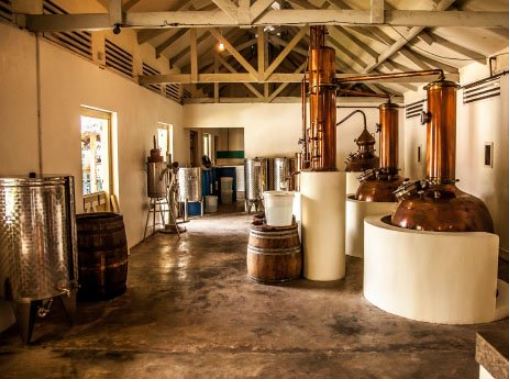

Amrut built on this success by releasing other whiskies in the years that followed, like the “Two Continents” which won India’s Whisky of the Year award in 2012. It also made the decision to polish up its semi-premium products, like the 2012 release of MaQintosh Silver Limited Edition blended malt whisky, which uses some of the same malt spirits that go into Amrut Fusion. At the same time, in a long overdue move, they upgraded their cheap rum in launching the Old Port Deluxe in 2009 (it was made from Indian molasses), and the Two Indies Rum several years later in 2013 (made from jaggery distillate and a blend of West Indian rums) – both are export-oriented, and aim to be more upscale products, though reactions and reviews in the rum world have been mostly middle of the road, primarily due to the lack of provided information on either, and the gradual fall from favour of blended and adulterated rums. To round out the decade, a new distillery was built at the same site as the existing distillery in Bengaluru, and commissioned in 2018, which increased capacity to a million litres annually.

Amrut built on this success by releasing other whiskies in the years that followed, like the “Two Continents” which won India’s Whisky of the Year award in 2012. It also made the decision to polish up its semi-premium products, like the 2012 release of MaQintosh Silver Limited Edition blended malt whisky, which uses some of the same malt spirits that go into Amrut Fusion. At the same time, in a long overdue move, they upgraded their cheap rum in launching the Old Port Deluxe in 2009 (it was made from Indian molasses), and the Two Indies Rum several years later in 2013 (made from jaggery distillate and a blend of West Indian rums) – both are export-oriented, and aim to be more upscale products, though reactions and reviews in the rum world have been mostly middle of the road, primarily due to the lack of provided information on either, and the gradual fall from favour of blended and adulterated rums. To round out the decade, a new distillery was built at the same site as the existing distillery in Bengaluru, and commissioned in 2018, which increased capacity to a million litres annually.

In 2019, to the shock and sorrow of many, Neelakanta Rao Jagdale passed away, two weeks before the company won the World Whisky Producer of the Year at the san Francisco Bartender’s Whisky Awards, going up against giants like Diageo and Pernod Ricard. In a move somewhat reminiscent of Google, the third generation — Rakshit Jagdale and his brother-in-law Vikram Nigam — took over, and shared Managing Director duties of Amrut Distilleries, a situation that persists to this day.

(c) Amrut Distilleries. Left to right: Vikram Nigam, Neelakanta Jagdale, and Rakshit Jagdale

There has been no large shakeups or news of note from Amrut since then, certainly not in the rumisphere, especially since COVID paused the world and it is only now getting back on its feet. Amrut Distilleries continues and for better or worse has tied their alcoholic future to three major prongs: local sales of semi-premium and cut-rate mass market products within India, reputation-making luxury whiskies globally, and the poor stepchild, rum, making up the remainder alongside other products like gins, brandies and vodkas (the Jagdale Group has many other commercial interests but I focus on the liquor segment here).

Old Monk rum might have been the bigger seller and the more famous name, and McDowell’s probably outsells it locally, but it was Amrut Distilleries which put Indian liquors on the world stage and gave them some respectability. It worked for whiskies, and perhaps now it is time for the rums as well, especially since the 2022 selection of their pot still jaggery rum for inclusion in the Habitation Velier range. There were plans to release a jaggery-based single-cask rum in August of 2022, Rakshit Jagdale said in a interview in June of that year…but I’ve seen nothing of that in the market so far, aside from a similar promise made in 2017, and the HV edition.

But the time may have come for Amrut to add to the success of the whisky segment and spend some time upgrading the rum portfolio: it should be expanded, premiumised, and allowed to take its place alongside the whiskies at last. Too long Indian rum has taken the low road and suffered for that by being ignored by serious enthusiasts in the larger drinking world, seen as less, and sold too often only to the diaspora. If old Neelakanta’s ambition, vision and risk-taking character have passed to the next generation, and they see the developments of the quality rum portfolios of so many new brands, then perhaps before too many years go by, we will see some seriously aged, unadded-to, unadulterated, pot-still, full-proof Indian rums of real quality come from Amrut. And it would be about damned time.

Rums

- Amrut Dark Rum

- Amrut XXX Classic Rum

- Amrut XXX Rum

- Old Port XXX Rum

- Old Port Deluxe Rum

- Old Port Deluxe Matured Rum

- Amrut Two Indies (Original)s

- Amrut Two Indies (Dark)

- Amrut Two Indies (White)

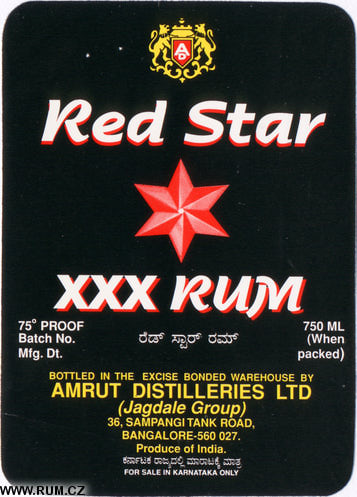

- Red Star XXX Rum

Main Timeline

- 1947 Establishment of Amrut Labs by a chemist, Radhakrishna Rao Jagdale

- 1948 Establishment of Amrut Distilleries

- 1949 Silver Cup Brandy introduced at state level in Karnataka

- 1962 Amrut XXX rum and Prestige XXX whisky sold to Indian Army

- 1972 Neelakanta Rao Jagdale (b.1953) joins his father in running Amrut

- 1976 JN Radhakrishna Rao Jagdale dies

- 1982 Malt whiskey begins to be made with grain; MaQintosh blended whiskey introduced

- 1986 Prestige Blended Malt Whisky begins to be sold to Canteen Stores Department

- 1987 New (and now primary) distillery built on a 4-hectare site in Kambipura, about 20 km from Bangalore

- 2002 Rakshit Jagdale begins testing customer appreciation in Newcastle-on-Tyne

- 2004 Amrut Indian Single Malt debuts in Cafe India in Glasgow

- 2005 Jim Murray gives Amrut Single Malt 82/100 points

- 2009 Fusion launches in UK; Old Port Deluxe rum is introduced

- 2010 Fusion launches in India

- 2010 Jim Murray rates Fusion as 3rd best in the world with 96.5 points.

- 2012 Amrut Two Continents rated Indian Whisky of the Year

- 2013 Fusion introduced in Mumbai; Amrut Two Indies Rum launches

- 2018 New distillery commissioned at Bangalore site: capacity increases to 1 million litres annually

- 2019 Neelakanta Rao Jagdale dies

- 2019 Amrut wins World Whisky Producer of the Year at Bartender’s Whisky Awards

- 2022 Amrut selected for Habitation Velier bottling

- 2023 Amrut Two Indies White introduced

General Sources

- Wikipedia – Amrut

- Whisky.Com database of distilleries

- Amrut home page

- JackSixWhisky (Polish) 2018 Biography of Amrut

Early years

Whisky

- The Hindu Metro Plus Bangalore March 2005 – “selling scotch to scots”

- Indian whisky overview with Amrut section, expanded here.

- Whisky scene in 1980s and 1990s and development of the single malt in Bangalore (good article on development of whisky). Also here in Business Today, 2019

- DNA India development of amrut

- Timeline and business outlook and development of whisky

- Business standard 2013 development of fusion

- Mint 2010 development of whisky and amrut

- For whiskey Lovers Amrut overview, undated

- Whisky.com good production article and brief history

- Economic times 2013 article on Desmondji “Pure Cane” rum and the section on 1980s development of whisky by Amrut and its problems (grain, ENS, regulation)

- Praj industries timeline

- 2021 Verve Magazine on the single malt revolution in India; good notes on social aspects

- Indian single malts Business Today India 2019 article

Current details

- Money Control 2022 interview with Rakshit Jagdale: future plans; Indian market; new distillery

- Money Control 2021 Other Indian rums plus Two Indies 2013

- SMB Story 2019 Third generation notes

- First Post 2019 Obit for Neelakanta Jagdale

- Rumporter 2018 Two Indies Rum

- LiveMint 2017 new distillery plans, planned jaggery-based rum

- FirstPost 2017 Good general company history

- First Post 2017 Amrut and single malt and John Paul, Radico Khaitan

- LiveMint 2013 Interview with Neelakanta Jagdale; plans, future releases, rums, whiskies

- Pete’s Rum Labels

Other Notes

Most newspaper and blog articles on the company focus on whisky, including technical details, sourcing of barley, the development of single malts and so on. While not downplaying this part of the company’s rich history, I have taken rum as my primary focus and so not lengthened the article needlessly with a deep dive into that aspect of Amrut’s operations. Interested readers can follow the sources of they wish to know more about it.

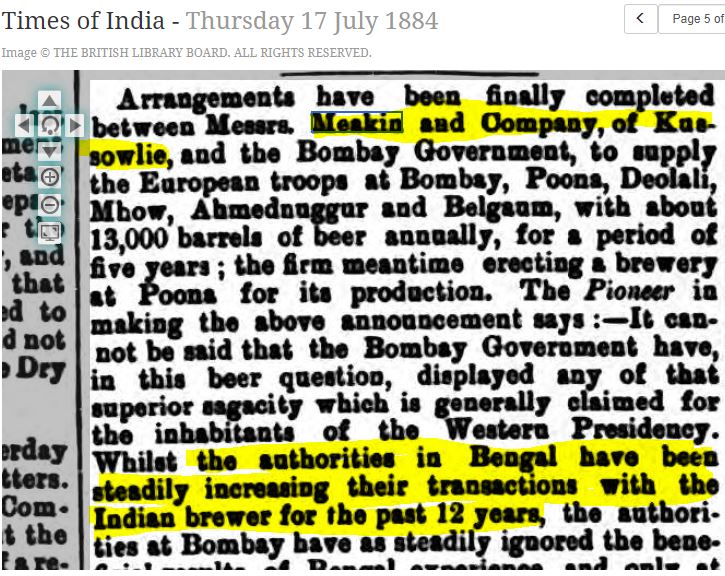

A consequence of this joint venture was that operations were restructured: brewing was suspended at Kasauli while upgraded, modernized and extended at Solan, and extensive malting continued at Kasauli. As the years moved on, modernization permitted increased production with the latest machinery and apparatus, and some of the unprofitable brewing centres were shuttered, with Solan, Kasauli and Lucknow being greatly expanded. Also, in April 1937, Burma became a separately administered colony of Great Britain, and operations there had to be separated from those of India for tax and administrative reasons. The Joint Venture at this point was retired and became a merged public company which was renamed with a complete lack of originality, to Dyer Meakin Breweries Ltd and this was listed on the London Stock Exchange.

A consequence of this joint venture was that operations were restructured: brewing was suspended at Kasauli while upgraded, modernized and extended at Solan, and extensive malting continued at Kasauli. As the years moved on, modernization permitted increased production with the latest machinery and apparatus, and some of the unprofitable brewing centres were shuttered, with Solan, Kasauli and Lucknow being greatly expanded. Also, in April 1937, Burma became a separately administered colony of Great Britain, and operations there had to be separated from those of India for tax and administrative reasons. The Joint Venture at this point was retired and became a merged public company which was renamed with a complete lack of originality, to Dyer Meakin Breweries Ltd and this was listed on the London Stock Exchange. It is likely for this reason, and perhaps also other subtle (and not so subtle) pressures brought to bear, that those family members of Meakins and Dyers remaining with the company, decided to dispose of their interest, and when a Brahmin ex-employee Narendra Nath Mohan raised appropriate funds and came to London in 1948, they made a deal to sell their shares (no further details available) and Mohan took ownership in 1949. The modern era of Mohan Meakin dates from this point, yet, interestingly, the name did not change and it remained Dyer Meakin Breweries for another seventeen years and the company did not diversify its alcoholic production into other areas for another five.

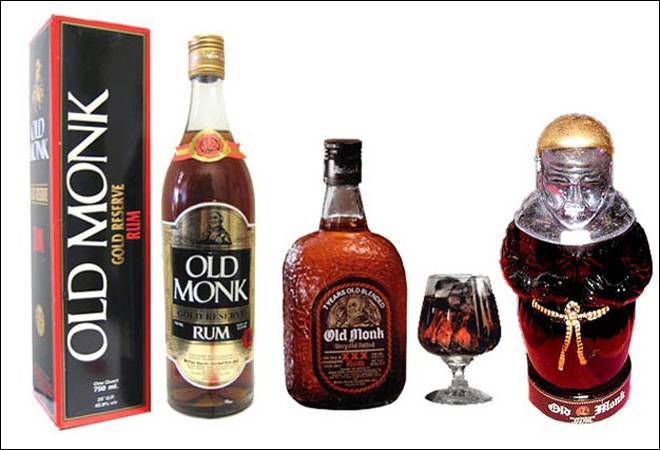

It is likely for this reason, and perhaps also other subtle (and not so subtle) pressures brought to bear, that those family members of Meakins and Dyers remaining with the company, decided to dispose of their interest, and when a Brahmin ex-employee Narendra Nath Mohan raised appropriate funds and came to London in 1948, they made a deal to sell their shares (no further details available) and Mohan took ownership in 1949. The modern era of Mohan Meakin dates from this point, yet, interestingly, the name did not change and it remained Dyer Meakin Breweries for another seventeen years and the company did not diversify its alcoholic production into other areas for another five. However, up to that point, the products made by the company remained what they always had been – whisky and beer. These were popular – Lion and Golden Eagle beers remained the most widely sold in India, with Solan No.1 doing the honours for whisky – but that was it. In the early 1950s, in an effort to diversify, NN and one of his three sons, Ved Ratan Mohan (“VR”), came up with what would become one of their signature, flagship brands, the Old Monk rum. VR, 26 at the time, wanted to channel inspiration he had taken from Benedictine monks in Europe, as well as to take on the Hercules rum sold exclusively to the armed forces (he retired a Colonel himself).

However, up to that point, the products made by the company remained what they always had been – whisky and beer. These were popular – Lion and Golden Eagle beers remained the most widely sold in India, with Solan No.1 doing the honours for whisky – but that was it. In the early 1950s, in an effort to diversify, NN and one of his three sons, Ved Ratan Mohan (“VR”), came up with what would become one of their signature, flagship brands, the Old Monk rum. VR, 26 at the time, wanted to channel inspiration he had taken from Benedictine monks in Europe, as well as to take on the Hercules rum sold exclusively to the armed forces (he retired a Colonel himself).

Old Monk was the market leader until about 2002 — not just in the rum field (which it comfortably dominated to that point) but the entire branded spirits market in the whole country, including whisky. And that included the other large spirit combine (United Spirits) whisky named Bagpiper. Even McDowell’s “Celebration” rum sold barely 50% of what Monk moved and in India the Monk was almost an icon of the local drinking scene, a rite of drunken passage for young college grads, the way Bacardi or the Kraken is in other places now.

Old Monk was the market leader until about 2002 — not just in the rum field (which it comfortably dominated to that point) but the entire branded spirits market in the whole country, including whisky. And that included the other large spirit combine (United Spirits) whisky named Bagpiper. Even McDowell’s “Celebration” rum sold barely 50% of what Monk moved and in India the Monk was almost an icon of the local drinking scene, a rite of drunken passage for young college grads, the way Bacardi or the Kraken is in other places now.

There are currently three distilleries of note on Réunion – Rivière du Mât,

There are currently three distilleries of note on Réunion – Rivière du Mât,

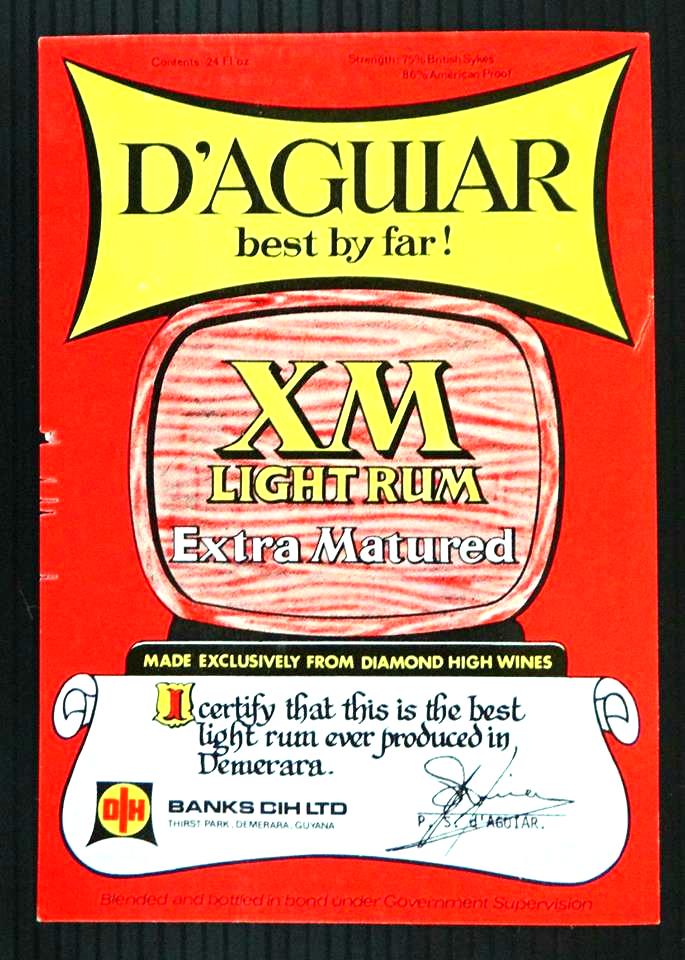

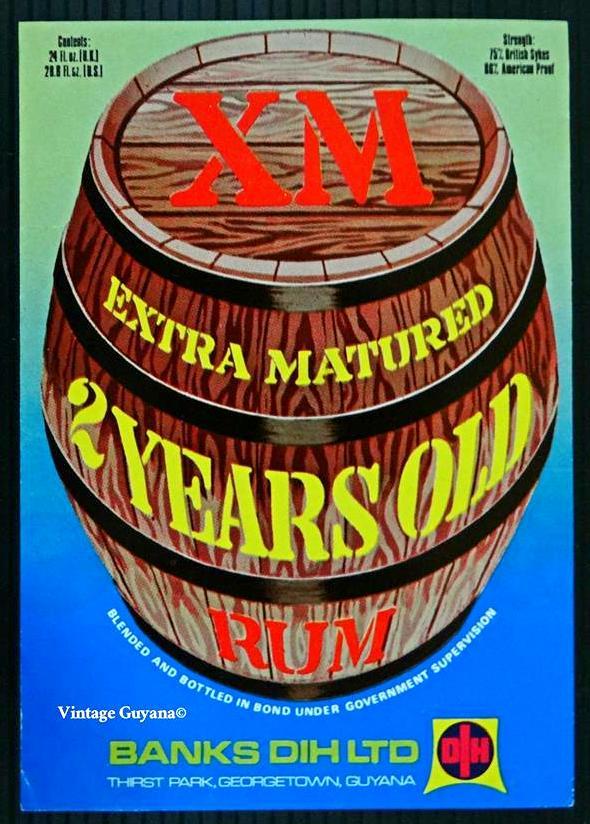

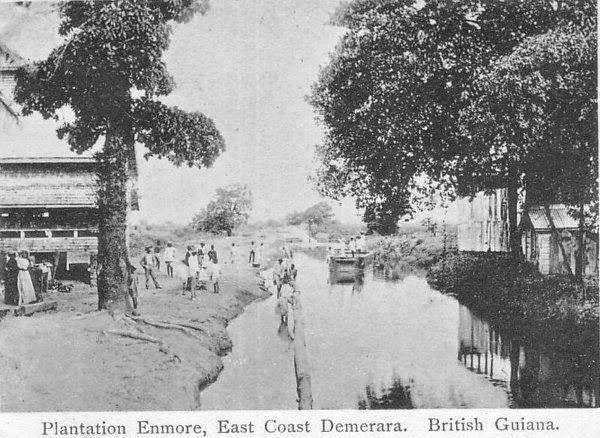

Banks certainly jumped on the bandwagon, and any Guyanese of my generation will remember the dark blue label of the XM five year old, and the lighter one of the ten year old. The ten in particular was, I believe, exported to the UK, USA and Canada (verification needed). The lower priced sub-ten year old rums like the Gold Medal, the Royal Gold or the Extra Matured rums were all noted as being Demerara rums, since (at that time) the concept of geographical appellations and protections with respect to rums had yet to gather any steam and was mostly relegated to the French islands.

Banks certainly jumped on the bandwagon, and any Guyanese of my generation will remember the dark blue label of the XM five year old, and the lighter one of the ten year old. The ten in particular was, I believe, exported to the UK, USA and Canada (verification needed). The lower priced sub-ten year old rums like the Gold Medal, the Royal Gold or the Extra Matured rums were all noted as being Demerara rums, since (at that time) the concept of geographical appellations and protections with respect to rums had yet to gather any steam and was mostly relegated to the French islands.

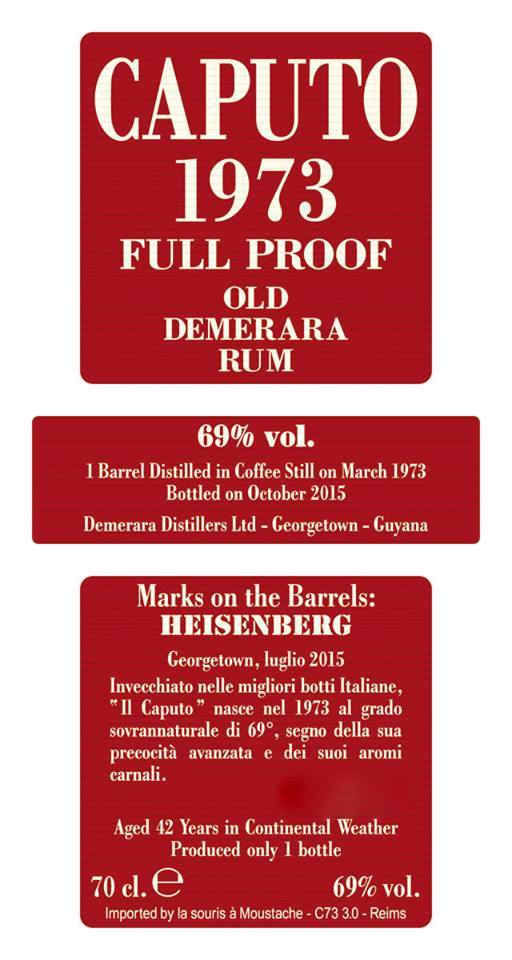

greater rum loving public – especially the aged Guyanese rums and the cask strength 60% Panamanian, which is surely quite an unusual product (I honestly can’t remember when was the last time I saw a full proof Panama rum). Henrik of RumCorner, as helpful as always, and who had spotted me the CDI Guadeloupe from there which I have to write about soon, informed me that “…those releases were done in collaboration with the Danish distributor. Denmark is one of the fastest growing markets for premium and ultra premium rums, so they asked CDI for some limited cask strength products and voila. In my opinion the Barbados FourSquare 60% rum [for example] really shows what is possible at high strength in comparison with the standard issue 40% horde.” Florent confirmed that, remarking “Once I started selling single cask to Denmark, my importer and his team told me that they’d like to know if I could bottle rums at cask strength. I told them that I could but due to duties, the prices in France would be too expensive and they wouldn’t sell so that they would have to buy the whole cask. [They did.] That’s why I decided to mention on the label that it was only bottled for Denmark…[Denmark] has quite an educated brown spirit clientele that are willing to pay a lot for pretty exclusive bottles. That’s mostly the story.

greater rum loving public – especially the aged Guyanese rums and the cask strength 60% Panamanian, which is surely quite an unusual product (I honestly can’t remember when was the last time I saw a full proof Panama rum). Henrik of RumCorner, as helpful as always, and who had spotted me the CDI Guadeloupe from there which I have to write about soon, informed me that “…those releases were done in collaboration with the Danish distributor. Denmark is one of the fastest growing markets for premium and ultra premium rums, so they asked CDI for some limited cask strength products and voila. In my opinion the Barbados FourSquare 60% rum [for example] really shows what is possible at high strength in comparison with the standard issue 40% horde.” Florent confirmed that, remarking “Once I started selling single cask to Denmark, my importer and his team told me that they’d like to know if I could bottle rums at cask strength. I told them that I could but due to duties, the prices in France would be too expensive and they wouldn’t sell so that they would have to buy the whole cask. [They did.] That’s why I decided to mention on the label that it was only bottled for Denmark…[Denmark] has quite an educated brown spirit clientele that are willing to pay a lot for pretty exclusive bottles. That’s mostly the story.