Like those tiny Caribbean islands you might occasionally fly over, the Maria Loca cocktail bar in Paris is so miniscule that if you were to sneeze and blink you’d go straight past it, which is what happens to us, twice. When Mrs. Caner and I finally locate it and go inside, it’s dark, it’s hectic, it’s noisy, the music is pounding and the place is going great guns. At the bar, along with two other guys, Guillaume Leblanc is making daiquiris with flair and fine style, greeting old customers and barflies and rumfest attendees, the shaker never still. Even though he doesn’t work there, he seems to know everyone by their first name, which to me makes him a top notch bartender even without the acrobatic or mixing skills.

In a dark corner off to the side are wedged Joshua Singh and Gregers Nielsen, a quartet of bottles in front of them. Part of the reason they’re here is to demonstrate the Single Barrel Selection of their Danish company (named “1423” after the number on that first barrel of rum the outfit ever bottled back in 2008) and how they fare in cocktails. Nicolai Wachmann and Mrs. Caner have been drafted to help out and I’m squished in there as well to do my review thing and take notes in the Little Black Book (since the Big Black Book didn’t fit into my pocket when I was heading out).

Three of these bottles are formal SBS releases by 1423, and there’s a Jamaican, a Trini and one from Mauritius. The fourth is a white-lightning tester from (get this!) Ghana, and I haven’t go a clue which one to start with. Nicolai has four glasses in front of him and somehow seems to be sipping from all four at once, no help there. Mrs. Caner, sampling the first of what will be many daiquiris this evening, and usually so fierce in her eye for quality rums, is raptly admiring Guillaume’s smooth drink-making technique while batting her eyes in his direction far too often for my peace of mind. Fortunately, I know he’s engaged to a very fetching young miss of his own, so I don’t worry too much.

“Any recommendations?” I ask the rotund Joshua who’s happily pouring shots for the curious and talking on background about the rums with the air of an avuncular off-season Santa Claus. How he can talk to me, pour so precisely, have an occasional sip of his own, discuss technical stuff and call out hellos to the people in the crowd all at the same time is a mystery, but maybe he’s just a better multi-tasker than I am.

“Try the Jamaican,” he advises, and disappears behind the bar.

“Not the Trinidadian?” I ask when he pops back up on this side, two new daiquiris in his hand. Mrs. Caner grabs one immediately, and, with the skill born of many vicious battles getting on-sale designer purses in the middle of frenzied mobs of other ladies, fends off Nicolai’s eager hands and shoves him into the wall in a way that would make a linebacker weep. He looks at me like this is my fault.

“It’s not a Caroni, so you might feel let down,” Josh opines, handing the second cocktail glass to another customer. “It’s Angostura, and you’re a rumdork, so…” He shrugs, and I wince.

Since I’m writing an on-again, off-again survey of rums from Africa (50 words and I’m done, ha ha), the Ghana white rum piques my interest, and I turn to Gregers, who is as tidy and in control as ever. I suspect he lined up his pens and papers with the edge of his desk in school. “The Ghana, you think?”

He considers for a moment, then shakes his head and pours me a delicate, neat shot of the Mauritius 2008. “Better start with this one. It’s a bit more…mellow. And anyway, you tried the Ghana last year in Berlin. If you need to, you can try it again later.”

He considers for a moment, then shakes his head and pours me a delicate, neat shot of the Mauritius 2008. “Better start with this one. It’s a bit more…mellow. And anyway, you tried the Ghana last year in Berlin. If you need to, you can try it again later.”

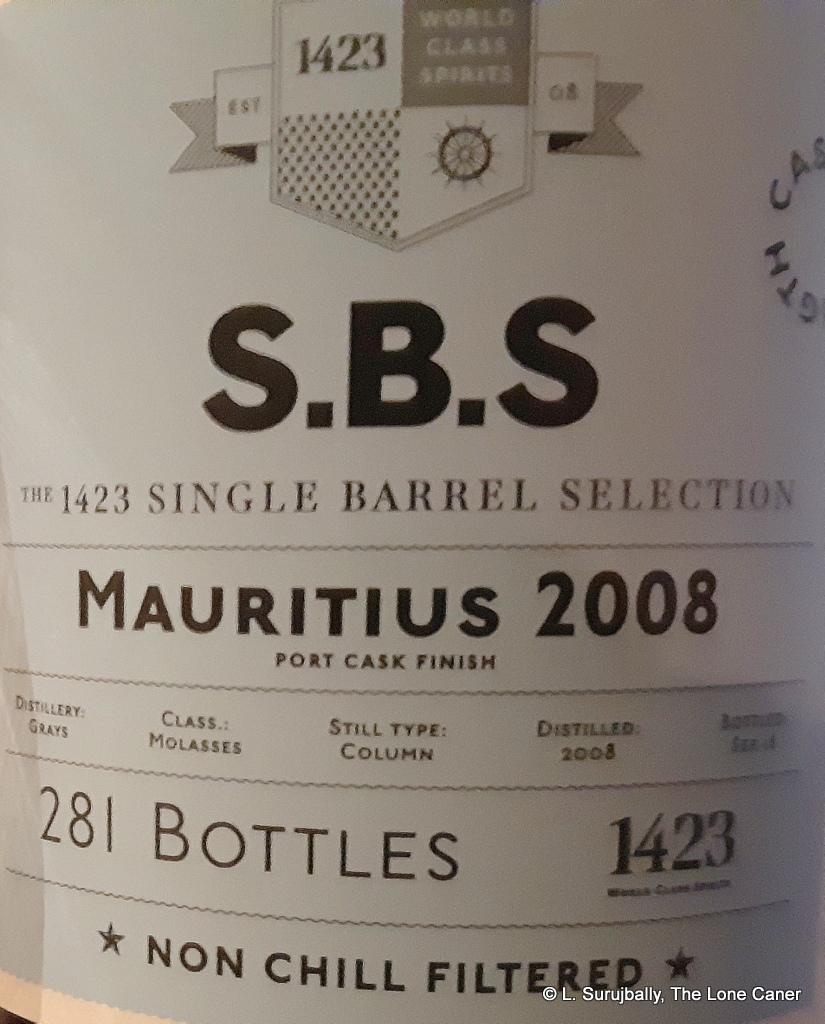

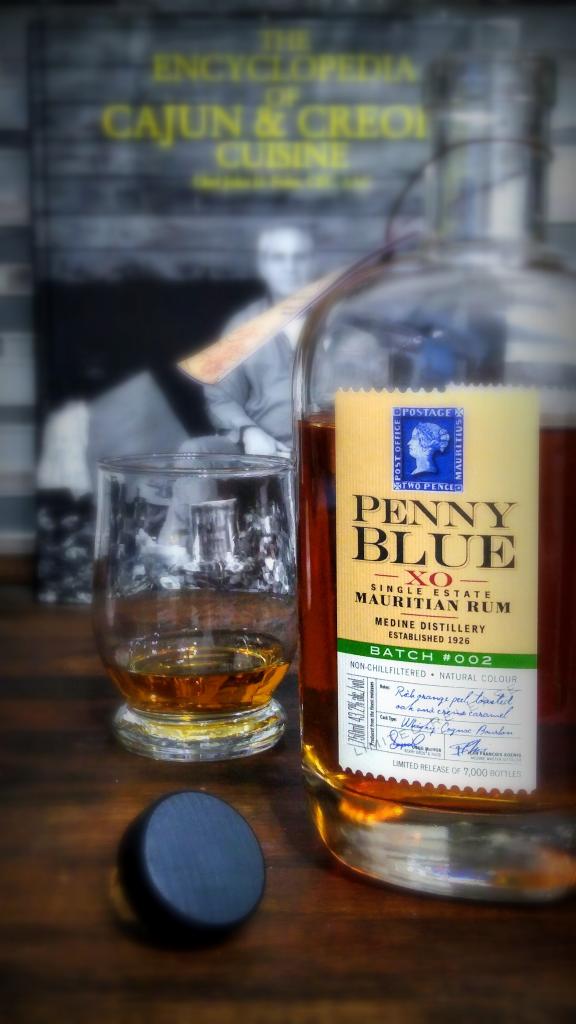

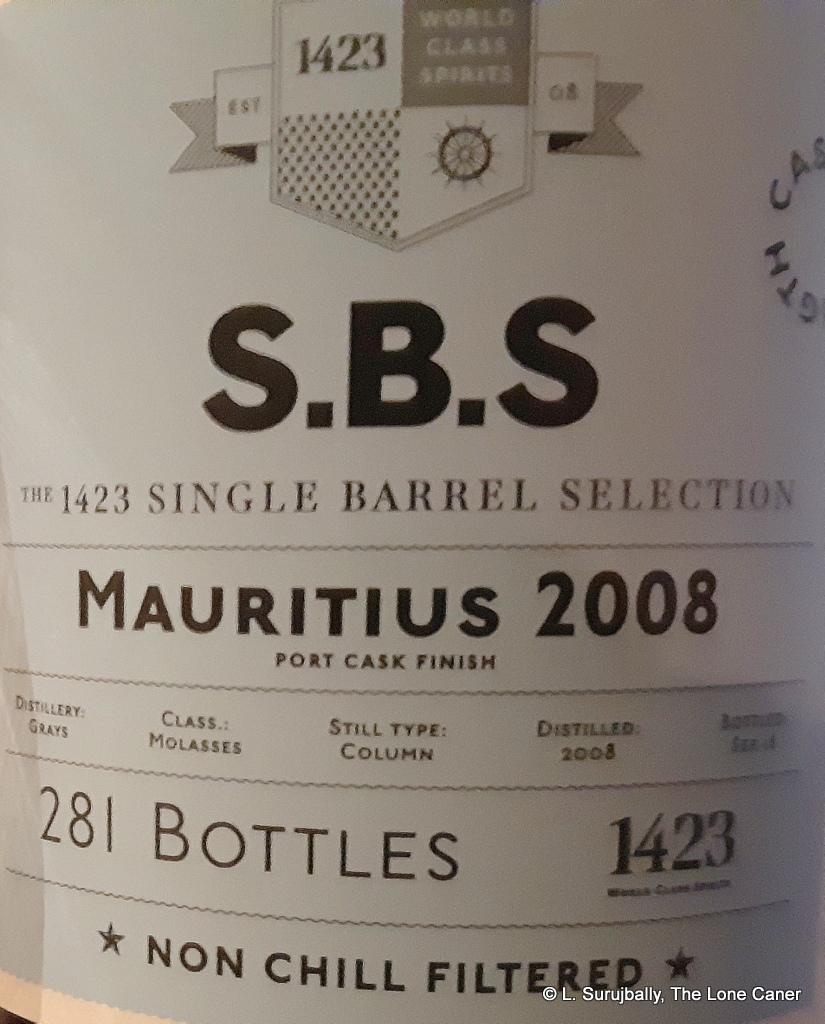

The rum winks invitingly at me. I take a quick moment to snap some pictures of the bottle, thinking again how far labels have come in the last decade. Velier started the trend, Compagnie des Indes provides great levels of detail, and others are following along, but what I’m seeing here is amazing. The label notes the distillery (Grays, which is a famed family name as well – they make the New Grove and Lazy Dodo line of rums but not the St. Aubins); the source, which in this case is molasses; the still type – column; distillation date – 2008; bottling date – 2018; and other throwaway details such as the non-chill-filtration, the port wine finish, the 281-bottle outturn, and the 55.7% ABV strength. I mean, you really couldn’t ask for much more than that.

I nose the amber spirit gently, and my eyes widen. Wow. This is good. It smells of toblerone, white chocolate, vanilla and almonds but there are also lighter and more chirpy notes swirling around that – gooseberries, ginger shavings, green grapes, and apples. And behind that are aromas of dark fruit like plums, prunes and dates, together with vague red-wine notes, in a very good balance. Musky, earthy smells mix with lighter and darker fruits in a really good amalgam – you’d never confuse this with a Jamaican or a Guyanese or a Caroni or a French island agricole. I glance over at Mrs. Caner to get a second opinion, but she’s ogling some glass-flipping thing Guillaume is doing and so I ask Nicolai what he thinks. He checks glass #2 on his table and agrees it is a highly impressive dram, just different enough from the others to be really interesting in its own way. He loves the way the finish adds to the overall effect.

As I’m scribbling notes into the LBB, I ask Gregers slyly, “Is there anything you’ve been told not to tell me about the rum?” He is like my brother, but business, blood and booze don’t always mix, trust is earned not freely given, and I’m curious how he’ll answer. Nicolai’s ears perk up and he pauses with his nose hanging over the third glass. Though he doesn’t talk much, his curiosity and rum knowledge are the equal of my own and he likes knowing these niggly little details too.

“Nope. Any question you have, we’ll answer.” Gregers and Joshua exchange amused looks. Truth to tell, there are two omissions which only a rum nerd would ask for or actively seek out. I wonder if they’re thinking the same thing I am. So:

“Additives? You don’t mention anything about them on the label.” And given how central such a declaration is these days to new companies who want to establish their “honesty” and street cred, an odd thing to have overlooked – at least in my opinion.

Joshua doesn’t miss a beat. He confirms the “no additives” ethos of the SBS line of rums, and it was not considered necessary to be on the label – plus, if some weird older gunk from Panama or Guyana, say, were to be bottled in the future and then found to be doctored by the original producer, maybe with caramel, then 1423 would not have egg over its face, which makes perfect sense. Then, before I ask, he and Gregers tell me that this rum is actually not from a single barrel but several casks blended together. Well…okay (there’s full detail in “other notes” below, for the deeply curious).

The bar is getting noisier, more crowded. Pete Holland of the Floating Rum Shack just turned up and is making the rounds, pressing the flesh, because he knows, like, everyone – alas, his pretty wife is nowhere in sight. Jazz and Indy Singh of Skylark are in-country but must have missed this event because no sign of their cheerful bearded forms. Yoshiharu Takeuchi of Nine Leaves is in center-court, telling a hilarious R-Rated story I cannot reprint here (much as I’d like to) of how he was mugged in Marseilles while taking a leak in an alleyway, and Florent Beuchet of the Compagnie is mingling – I shout a hello at him over the heads of several customers. He waves back. The cheerfully bearded and smiling Ingvar “Rum” Thomsen (journalist and elder statesman of the Danish rum scene) is hanging out next to his physically polar opposite, Johnny Drejer (tall, slim, clean-shaven); Johnny and I briefly discuss the new camera I helped him acquire, and some of his photographs and the state of the rumiverse in general. There are probably brand reps and other French rumistas in attendance, but I don’t recognize anyone else and the ones I do know are AWOL: Laurent is still on his round the world expedition with his family (but not the poussette), Cyril doesn’t attend these things and I don’t know Roger Caroni by sight. All I can see is that everyone is enjoying themselves thoroughly and the loud hum of intense and excited (and perhaps drunken) conversation is electric. The energy level of the bar is off the scale.

Guillaume has finished his cocktail twirling demo and lost my wife’s attention, I note happily. He’s mixing more drinks for another small group of people who just wandered in. Mrs. Caner is now deep in conversation with Nicolai about his marital status and that of her entire tribe of single female relatives. After landing me like a prize trout all those years ago, my pretty little wife has developed a raging desire to “help out” any single person of marriageable age — and she’s seen Hitch like forty-seven times, which doesn’t help. Anyway, they’re both ignoring the rums in front of them, so I roll my eyes at this blasphemy and continue on to the tasting.

And let me tell you, that Mauritius rum tastes as good as it smells, if perhaps a little sharper and drier on the tongue than the aromas might suggest. It really is something of a low-yield fruit bomb. Raspberries, strawberries, lemon peel, ginger and sherbet partied hard with the deeper flavours of prunes, molasses, vanilla, nuts, chocolate mousse, ice cream and caramel…and a touch of coca cola, tobacco and seaweed-like iodine. There’s even a sly hint of brine, thyme, and mint rounding things off, transferring well into a lovely smooth finish dominated by candied oranges, a sharp line of citrus peel, and a very nice red wine component that completes what was and remains, a really very good drink. It is like a curiously different Barbados rum, with aspects of Guyana and Jamaica thrown in for kick, but its quality is all its own, and hopefully allows the island to get more press in the years to come. For sure it is a rum to share around.

With some difficulty, I manage to catch Mrs. Caner’s eye and pass the glass over to her, because I think this is a rum she’d enjoy too. Somehow even after all the daiquiris she’s been getting, her eyes are clear, her speech is unslurred, her diction flawless, and I may be biased but I think she looks absolutely lovely. As she tries the SBS Mauritius, I can see she appreciates its construction as well and she compliments Joshua and Gregers on their selection. “This is great,” she remarks, then provides me with a whole raft of detailed tasting notes, which I have mysteriously lost and none of which somehow have made it into this essay.

Nicolai, over in his corner, is happy to cast some other comments on to the table regarding the SBS Mauritius, all positive. We all agree, and I tell Gregers, that this is one fine rum, and if I could, I’d buy one, except that I can’t. My wife, having delivered herself of her earth shaking opinion, immediately beelines over to the bar area where Guillaume’s fiancee and sister have just arrived, most likely because she’s had enough of all the testosterone in our corner and wants some real conversation with people who are specifically not certifiable about rum.

L-R – Nicolai, Gregers, Guillaume, Joshua and one of the bartenders from that evening whose name I did not get, sorry.

I want some fresh air so Joshua and I go outside the bar for a smoke (the irony does not escape us). The nighttime air of Paris is crisp and cool and I remember all the reasons I like coming here. We discuss 1423 and their philosophy, its humble beginnings more than ten years ago, though that remains outside the scope of this essay.

“So, the Mauritius was pretty good,” I remark, pleased to have started off this fest (and 2019) on a good rum, a tasty shot. He courteously does not ask for my score which for some obscure reason is all that some people want. “What do you think I should try next?”

He smiles, reminding me once again of Santa Claus in civilian clothes and taking a breather from gift giving, mingling with the common folk. “Oh the Jamaica, for sure. That’s a DOK, PX finished, pot still aged in 40-liter barrels…and let me tell you, there’s some really interesting stories behind that one -”

I stop him. My fingers are twitching. “Hang on. I gotta write that down. Let’s go inside, pour a shot, and you can tell me everything I need to know while I try it. I don’t want to miss a thing.”

And while it’s not exactly relevant to the Mauritius rum I’m supposed to be writing about here, that’s pretty much what we ended up doing, on a cool evening in the City of Lights, spent in the lively company of my beautiful wife, and assorted boisterous, rambunctious geeks, reps, writers, drinkers, bartenders and simply good friends. You just can’t do a rum tasting in better surroundings than that.

(#620)(87/100)

Other Notes

- In one of those curious coincidences, the Fat Rum Pirate penned his own four-out-of-five star review of the same rum just a few days ago. However, the first review isn’t either of ours, but the one from Kris von Stedingk, posted in December 2018 on the relatively new site Rum Symposium. He was also pretty happy with it

- Background on the rum itself:

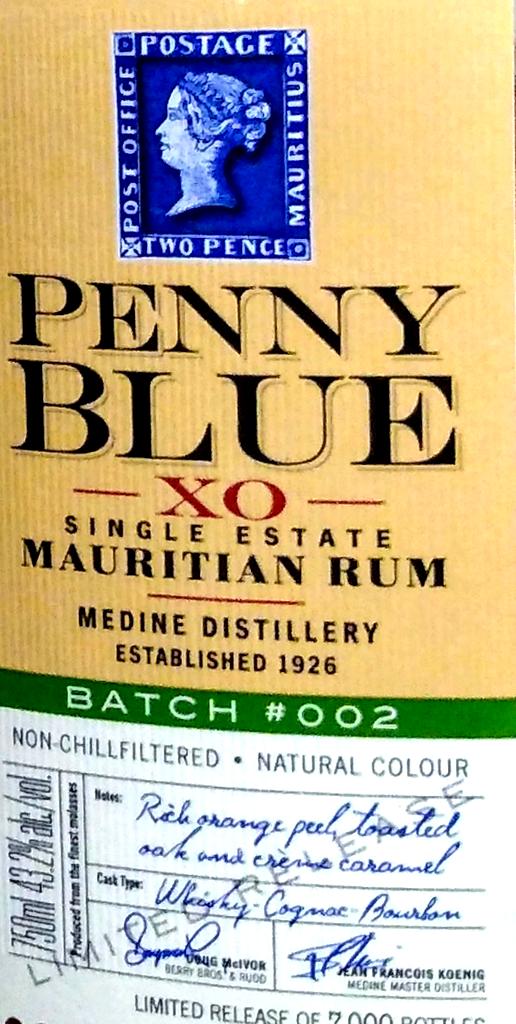

- Joshua met with a rep from Grays from Mauritius a few years ago at the Paris Rhumfest; he brought a number of different cask samples from the warehouse. 1423 ended up choosing two, which were about 9 years at this time

- The first was aged seven years in a 400-liter French Limousin oak, followed by two more in Chatagnier (Chestnut).

- The second was again aged seven years in a 400-liter French Limousin oak, followed by two years in Port.

- 1423 ordered both of them but ended up receiving 400 liters of the Chatagnier cask and 120 liters of the Port both now with another ageing year in their respective casks. All of this was blended together when delivered to Denmark and the 2018 release was basically the first 200 liters, all tropical aged. The remaining 320 liters are still in the Denmark warehouse waiting for a good idea and the right time to release.

What surprised me about the rhum (for so we shall term it since it can’t be called an agricole) was how much like a Cabo Verde grogue it was. The nose, for example, channelled some of that same almost easy, relaxed scents as, oh, the Barbosa. Nosing something like a dry white wine, it was redolent of freshly mown grass, green grapes and apples, sweet, light, and almost — but not quite — delicate. Cherries, raspberries and a touch of sour cider followed, as well as a sly hint of brininess after a few minutes. Overall, the aroma had a distinctly agricole vibe to it, which of course was unsurprising. I liked it a lot.

What surprised me about the rhum (for so we shall term it since it can’t be called an agricole) was how much like a Cabo Verde grogue it was. The nose, for example, channelled some of that same almost easy, relaxed scents as, oh, the Barbosa. Nosing something like a dry white wine, it was redolent of freshly mown grass, green grapes and apples, sweet, light, and almost — but not quite — delicate. Cherries, raspberries and a touch of sour cider followed, as well as a sly hint of brininess after a few minutes. Overall, the aroma had a distinctly agricole vibe to it, which of course was unsurprising. I liked it a lot. Now me, I like white rums. Not the over-filtered, clear, bland, anonymous and unaromatic cocktail fodder that clogs up far too many glasses, but clusterbombs of flavour like clairins or grogues, or the white lightning from Saint James, DDL, Depaz, Capovilla, Worthy Park, A1710, Issan, Savanna….well, the list is long, what can I say? Here’s another one to add to the list – it’s not fierce or feral, and doesn’t want to cause you pain. It is simply a compact and neat homunculus of a rumlet with oodles of flavour that dance and cavort across the senses, and one that I will remember with great fondness.

Now me, I like white rums. Not the over-filtered, clear, bland, anonymous and unaromatic cocktail fodder that clogs up far too many glasses, but clusterbombs of flavour like clairins or grogues, or the white lightning from Saint James, DDL, Depaz, Capovilla, Worthy Park, A1710, Issan, Savanna….well, the list is long, what can I say? Here’s another one to add to the list – it’s not fierce or feral, and doesn’t want to cause you pain. It is simply a compact and neat homunculus of a rumlet with oodles of flavour that dance and cavort across the senses, and one that I will remember with great fondness.

La Rhumerie de Chamarel, that Mauritius outfit we last saw when I reviewed their 44% pot-still white, doesn’t sit on its laurels with a self satisfied smirk and think it has achieved something. Not at all. In point of fact it has a couple more whites, both cane juice derived and distilled on their

La Rhumerie de Chamarel, that Mauritius outfit we last saw when I reviewed their 44% pot-still white, doesn’t sit on its laurels with a self satisfied smirk and think it has achieved something. Not at all. In point of fact it has a couple more whites, both cane juice derived and distilled on their

Personally I have a thing for pot still hooch – they tend to have more oomph, more get-up-and-go, more pizzazz, better tastes. There’s more character in them, and they cheerfully exude a kind of muscular, addled taste-set that is usually entertaining and often off the scale. The Jamaicans and Guyanese have shown what can be done when you take that to the extreme. But on the other side of the world there’s this little number coming off a small column, and I have to say, I liked it even more than its pot still sibling, which may be the extra proof or the still itself, who knows.

Personally I have a thing for pot still hooch – they tend to have more oomph, more get-up-and-go, more pizzazz, better tastes. There’s more character in them, and they cheerfully exude a kind of muscular, addled taste-set that is usually entertaining and often off the scale. The Jamaicans and Guyanese have shown what can be done when you take that to the extreme. But on the other side of the world there’s this little number coming off a small column, and I have to say, I liked it even more than its pot still sibling, which may be the extra proof or the still itself, who knows.

Although cold stats alone don’t tell the tale, I must confess to being intrigued, since a primary producer’s limited single-barrel expressions tend to be somewhat special, something they picked out for good reason. That felt like the case here – the initial smell was delicious, of burnt oranges and whipped cream (!!), a sort of liquid meringue pie if you will. It negotiated the twists and turns of tart and mellower aromas really well: honey, fruits, raisins, green apples, grapes,and ripe peaches. There was never too much of one or the other, and it was all quite civilized, soft and even warm

Although cold stats alone don’t tell the tale, I must confess to being intrigued, since a primary producer’s limited single-barrel expressions tend to be somewhat special, something they picked out for good reason. That felt like the case here – the initial smell was delicious, of burnt oranges and whipped cream (!!), a sort of liquid meringue pie if you will. It negotiated the twists and turns of tart and mellower aromas really well: honey, fruits, raisins, green apples, grapes,and ripe peaches. There was never too much of one or the other, and it was all quite civilized, soft and even warm Background history

Background history

Certainly the 2003 10 YO does its next-best relative the

Certainly the 2003 10 YO does its next-best relative the

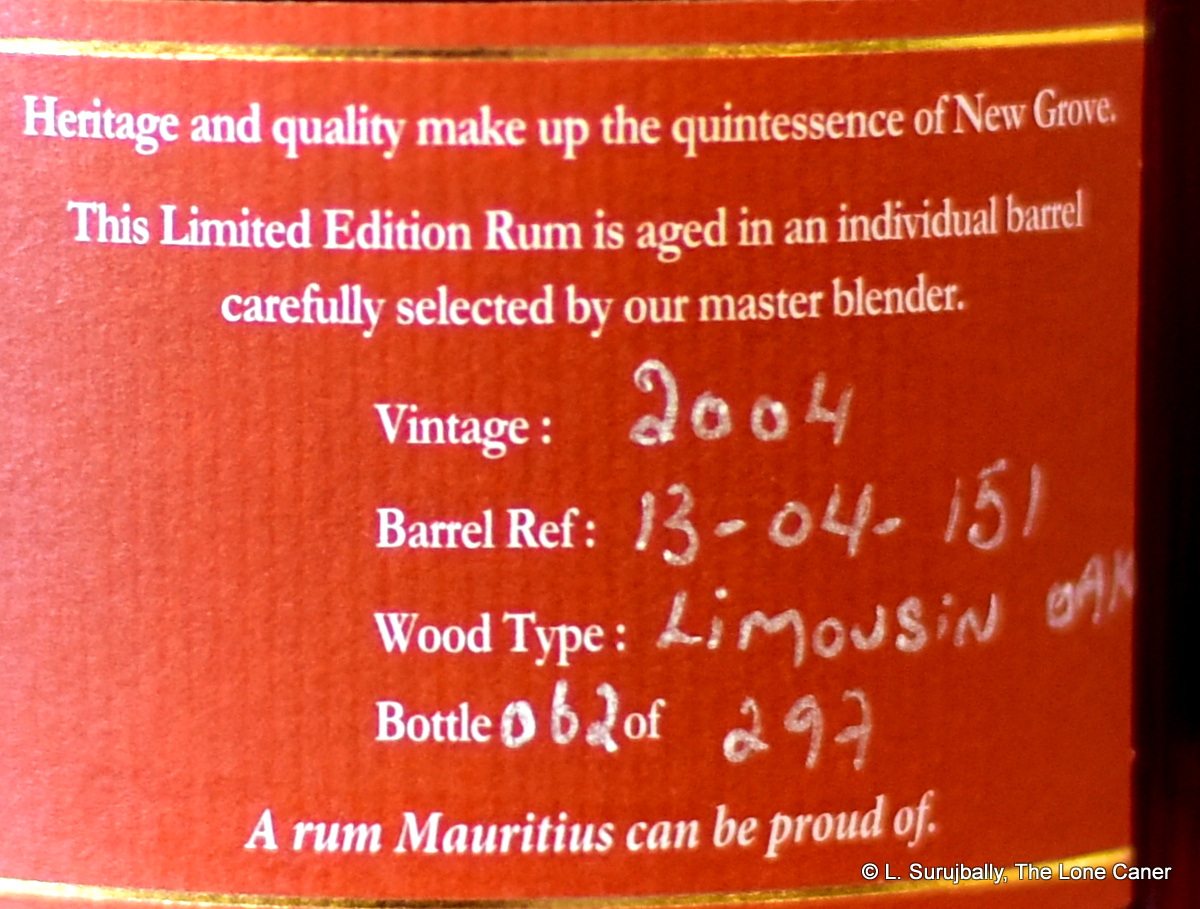

Brief stats: a 4 year old rum distilled in September 2014, aged in situ in French oak casks and bottled in February 2019 at a strength of 58% ABV. Love the labelling and it’s sure to be a fascinating experience not just because of the selection by Velier, or its location (we have tried few rums from there though those

Brief stats: a 4 year old rum distilled in September 2014, aged in situ in French oak casks and bottled in February 2019 at a strength of 58% ABV. Love the labelling and it’s sure to be a fascinating experience not just because of the selection by Velier, or its location (we have tried few rums from there though those

He considers for a moment, then shakes his head and pours me a delicate, neat shot of the Mauritius 2008. “Better start with this one. It’s a bit more…mellow. And anyway, you tried the Ghana last year in Berlin. If you need to, you can try it again later.”

He considers for a moment, then shakes his head and pours me a delicate, neat shot of the Mauritius 2008. “Better start with this one. It’s a bit more…mellow. And anyway, you tried the Ghana last year in Berlin. If you need to, you can try it again later.”

See, while furious aggression

See, while furious aggression

The nose told a tale that would be repeated right down the line, and what I smelled was pretty much what I tasted, with a few variations here and there. It was light and clean, yet displaying darker, muskier spicier notes as well: vanilla, coffee, licorice and some sharp tannins, with the musty long-disused-attic tastes remaining. Some fruits – peaches and cherries for the most part – stayed in the background. The core was anise and sawdust and unsweetened chocolate, and overall it presented as somewhat dry. Quite nice — if it fell down at all it was in the finish, which was more licorice and chocolate, thin tart fruits (gooseberries perhaps) and after a few hours, it took on a metallic tang of old ashes doused with water that I can’t say I entirely cared for.

The nose told a tale that would be repeated right down the line, and what I smelled was pretty much what I tasted, with a few variations here and there. It was light and clean, yet displaying darker, muskier spicier notes as well: vanilla, coffee, licorice and some sharp tannins, with the musty long-disused-attic tastes remaining. Some fruits – peaches and cherries for the most part – stayed in the background. The core was anise and sawdust and unsweetened chocolate, and overall it presented as somewhat dry. Quite nice — if it fell down at all it was in the finish, which was more licorice and chocolate, thin tart fruits (gooseberries perhaps) and after a few hours, it took on a metallic tang of old ashes doused with water that I can’t say I entirely cared for.

According to my email exchanges with the company, the rhum was produced from the harvest of 2005, and is a blend of two rhums – pot still (30%) aged ten years aged in ex-bourbon barrels, and column still (70%) stored in inert inox tanks; both distillates deriving from cane juice . As a further note, although sugar was explicitly communicated to me as

According to my email exchanges with the company, the rhum was produced from the harvest of 2005, and is a blend of two rhums – pot still (30%) aged ten years aged in ex-bourbon barrels, and column still (70%) stored in inert inox tanks; both distillates deriving from cane juice . As a further note, although sugar was explicitly communicated to me as