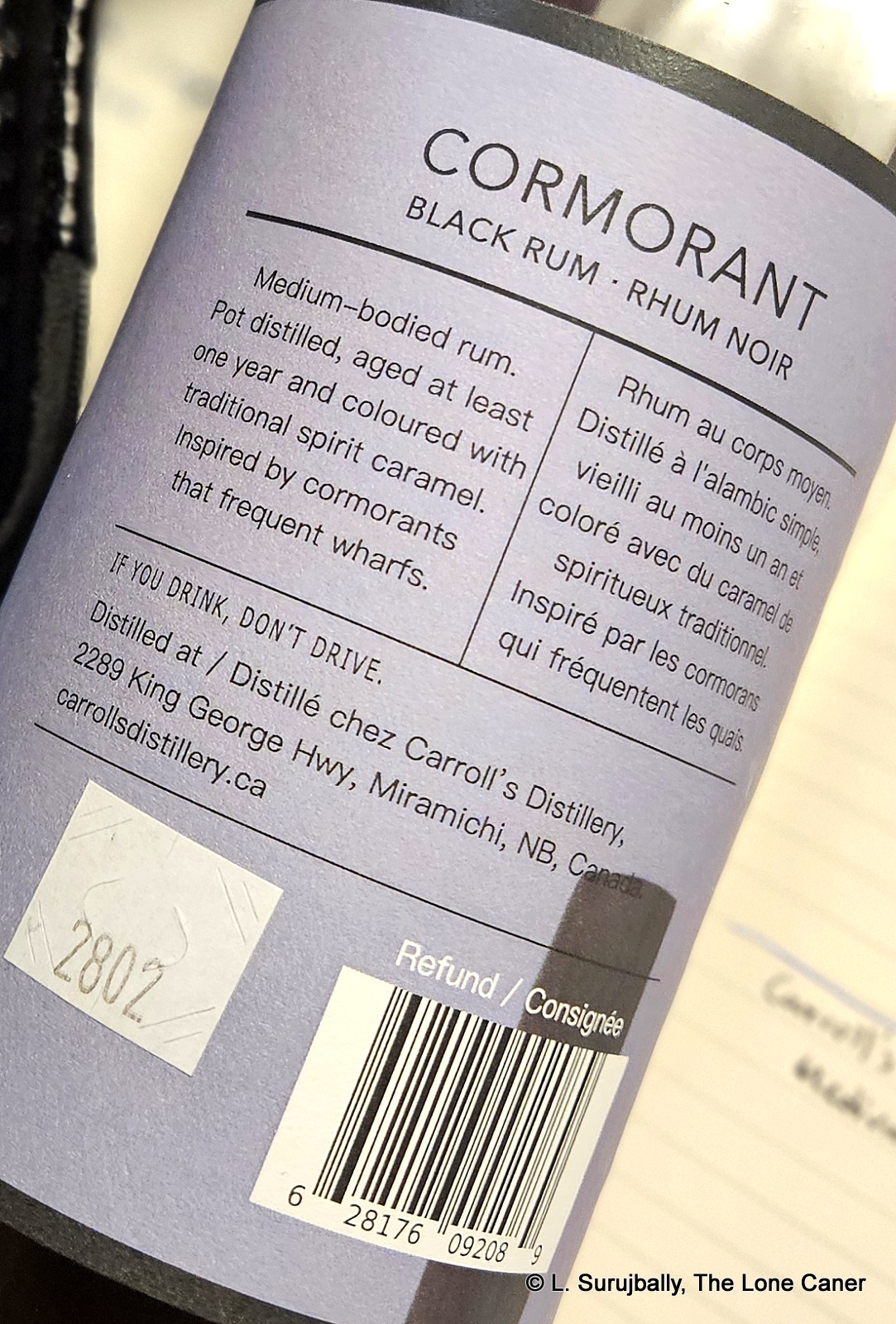

Today we conclude our quick run through of the rums made by Carroll’s Distillery in New Brunswick, by addressing the “Cormorant” “black” rum. For all that it implies, it’s a medium bodied rum, more dark brown than black, from a pot still, slightly more aged than those rums we have looked at so far, and costing a shade more (Can$36). And while it started out generating indifference, I did warm up to it over time.

As before, Carroll’s uses Crosby Fancy molasses, and a seven day fermentation, after which the wash is run twice through the the pot still, and the resulting distillate aged for a minimum of one year in 200L ex bourbon casks. Caramel colouring is added to darken the colour and add a little extra oomph to the profile. The blend can vary – a current batch in 2024, for example, was made up of half 2YO and half 20 month old rum stocks.

Dark (or as this one is called, “black”) rums are a mixing agent called for by many cocktail recipes, and because his distillery is a new one and this juice is consequently very young, Matthieu Carroll, the owner, doesn’t really have much choice: a cocktail ingredient is what he’s making with the stocks he’s managed to age. That the rum is as decent as it is, is a rebuke to all those Canadian distilleries out there who actively seek the milquetoast, tasteless low ground in an effort to chase the mass market.

Dark (or as this one is called, “black”) rums are a mixing agent called for by many cocktail recipes, and because his distillery is a new one and this juice is consequently very young, Matthieu Carroll, the owner, doesn’t really have much choice: a cocktail ingredient is what he’s making with the stocks he’s managed to age. That the rum is as decent as it is, is a rebuke to all those Canadian distilleries out there who actively seek the milquetoast, tasteless low ground in an effort to chase the mass market.

Because look at what he’s managed to accomplish here: now the nose starts kind of weak, true, with cola, citrus, and caramel, plus a few hints of vanilla and brown sugar thrown in. Easy to smell, very traditional stuff. It also presents a few heavy fleshy fruits, quite ripe, and a touch of baking spices, hard to make out, and if I was to summarize the nose it would be to say it smells like a rum and coke in a bottle, minus the citrus.

The palate is where there is initially unimpressive. It’s not that the mouthfeel is bad, or that it’s too indistinct, or too weak – although there’s some truth to that, because it starts out that way. When one starts sipping to check it out, there’s seems to be rather little to become enthusiastic about. It has some brine, faint bitter chocolate (very faint), some sweet, a few fruits – peaches, apricots, overripe red apples, red grapes – and it’s all gone almost immediately, poof, before one has time to come properly to grips with it.

Yet as it stands, it develops more legs than it started with, and to me that’s what makes it worth trying. The nose develops and becomes a bit richer, the cinnamon and cola meld better and the fruits become slightly more distinct; molasses, coffee and the bite of citrus also emerge a bit more assertively on the palate; and the finish, while staying the same, lasts a decent amount of time and is tasty as all get out. It reminds me of some of the younger Demerara rums DDL has, if not quite as pungent.

Admittedly, the rum is living room strength and there’s only so much you can squeeze out of such a product. And yep, I had the peace of a weekend and the time to be able to come to grips with it, which is very different from the busy, conversation-filled social situations in which many will try it (and most won’t care anyway – into the mix it goes, without any ceremony, as a rule, and to hell with the snooty reviewers’ tasting notes).

Admittedly, the rum is living room strength and there’s only so much you can squeeze out of such a product. And yep, I had the peace of a weekend and the time to be able to come to grips with it, which is very different from the busy, conversation-filled social situations in which many will try it (and most won’t care anyway – into the mix it goes, without any ceremony, as a rule, and to hell with the snooty reviewers’ tasting notes).

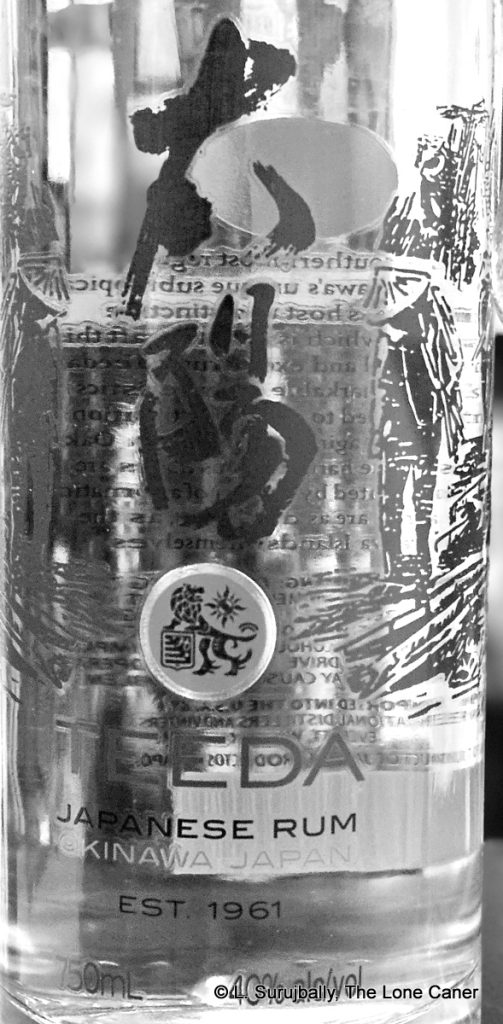

So in a way, it’s a pity that the distribution is so limited, and the output of this micro distillery is (in relative terms) so small – unless ordered in-country (as I did), most people will likely never buy it, or care enough to bother. Yet I maintain that this under-the-radar rum is worth a look — it’s a smidgen better than it seems, and deserves perhaps a few more minutes of one’s time to appreciate to the fullest. So many rums entice you to buy them on the basis of a cool label, a famed distillery, or by maxing the mojo: torqued up strength, puissant congener counts, geriatric ageing, that kind of thing. Here we have a label that has nothing to do with rum and is simply art, from an almost unknown distillery that sports no in-your-face big stats. At first blush the “Cormorant” doesn’t seem to be all that special, but I think that if left to its own devices and allowed to open up, it does give a pretty good account of itself.

(#1108)(84/100) ⭐⭐⭐½

Other notes

- Video Recap is here.

- The distillery does sell (and mail) rums on its website and for those who want to dip their toes in before going the whole hog, there are small 200ml bottles of each expression available for under ten bucks, which are godsends to penurious reviewers and which I wish more producers could issue.

- The artwork on the label was a lightly edited photograph, used with permission.

Company Bio

Company Bio