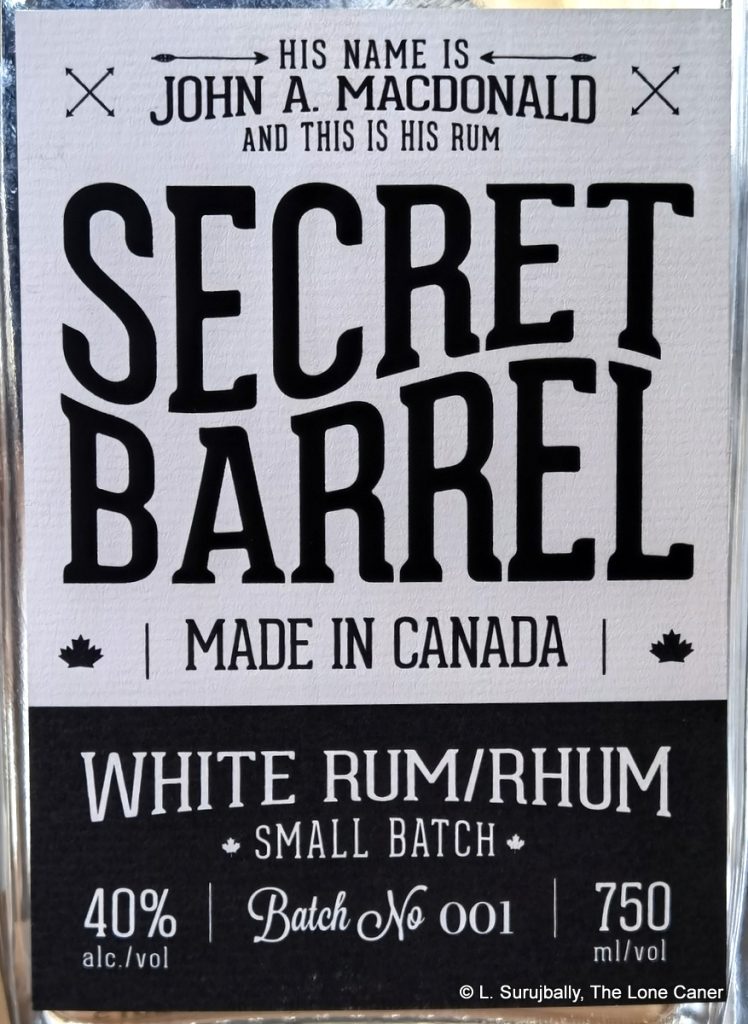

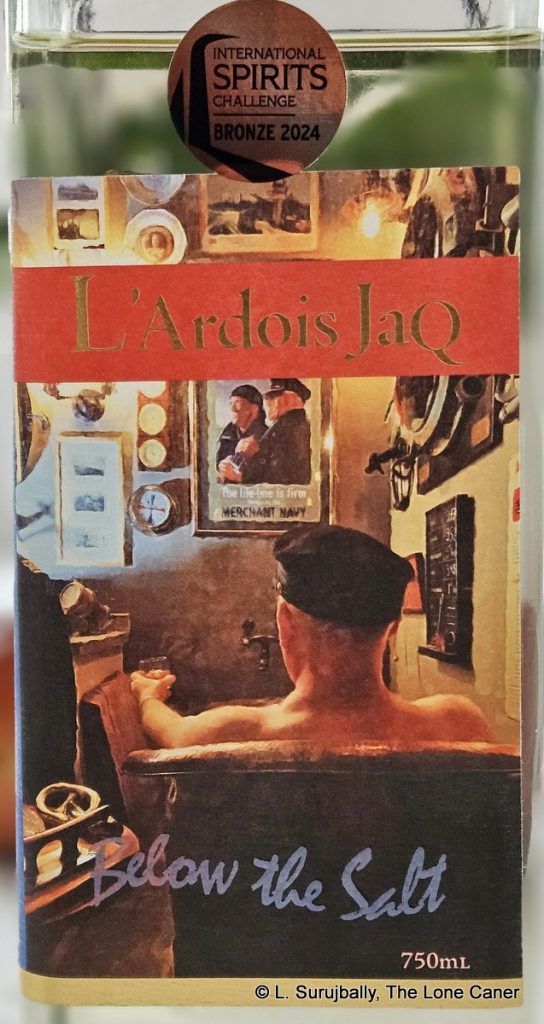

For those who trawl the Canadian rum scene and occasionally despair at ever finding a locally made hooch that would blow their hair back and wow their pants off, well, I have a new candidate for you: the very tasty, lightly (very lightly) aged, almost-white stinker of a rum called L’Ardois JaQ, made by a recently opened craft distillery in Nova Scotia run by (and I shit you not) a tug boat captain I met named Gregg Colp, whose business card very appropriately gives his position as “Chief Adept and Bottle Filler” and sort of gives you a flavour for the whole operation.

That preamble requires a lot of unpacking, so bear with me.

Captain Colp – you gotta love the name – is indeed a tug boat captain for the Arctic sealift. He has been involved in making one form of alcoholic beverage or other, legal or not, commercial or otherwise, since he was a pilchard brewing illicit beer in his backyard. Having studied chemistry at Uni, he then got his master’s ticket and spent the next decades travelling around the Caribbean and other parts of the distilling world, which included interning in Cognac for a venerable maison there (no, not the one you’re thining of) just because it sounded like fun and he wanted to know more about the entire process. The man, you can tell, loved rum.

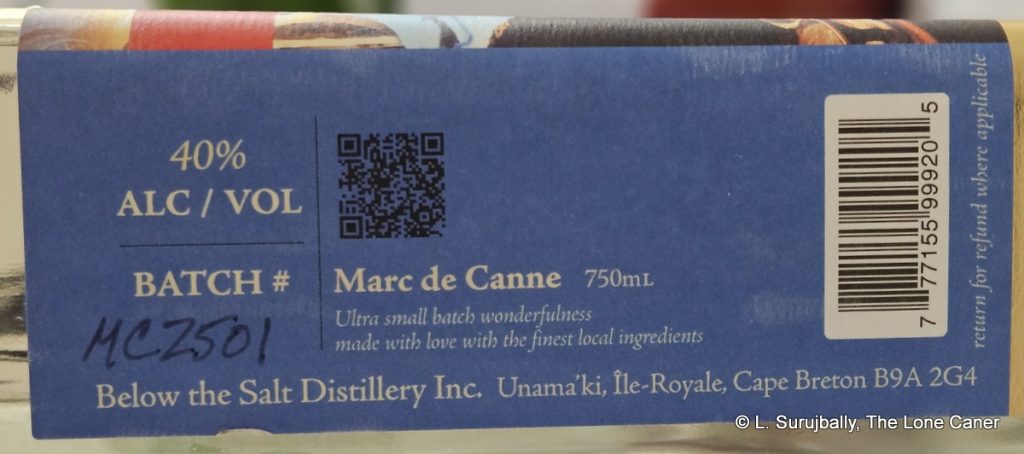

Anyway, some years ago, as cruel eld frosted his hair and bit at his bones (while simultaneously deflating parts he preferred to remain inflated) he decided he wanted a retirement plan, something to ward of the chill, make a few bucks and indulge his maritime proclivity for rum. After trawling around and consolidating his experience (to augment what he already had amassed in a lifetime of globetrotting, and that’s a lot) and sourcing a double retort pot still, he and his partner Vikki Piersig (her card reads “Chief Mate and gal who makes the distiller and most everything else look good” – people, I cannot make this stuff up!) set up shop as a small distillery in a landaway in Highway 4 in Nova Scotia (very close to the shore dividing it from Cape Breton where his office premises are). In point of fact, as a throwaway factoid, he was offered the opportunity to take over Vernon Walters blacksmith shop in the 1990’s (when he was sailing on the Bluenose itself), long before Ironworks came on the scene and took over the premises to launch Ironworks Distillery. Small world.

That irreverent sense of humour exemplified by the business cards is to some extent also represented by the name of the distillery – Below the Salt. While in today’s world salt is something of a commodity whose major use is a feedstock for industrial chemicals, for most of history it was a tradeable good much used for nutrition and preserving food; trade routes were opened to search for new supplies, and as late as 1860, wars could be fought over it. In medieval times it was a precious resource not often seen except on the tables of the rich, where small pots of the stuff were placed halfway down a noble’s long dining table. The lords, ladies and exalted ones (which is to say, not us) sat “above the salt” as a mark of their lofty station, while us peasants, rabble, assorted commoners and lowlifes sat “below the salt” – and it’s clear where the Chief Adept’s preferences and antecedents lie.

Since Calgary is known for its maritime waterways, it was just a matter of time before Captain Colp sailed into my area with a blatting tantaraa of trumpets, all flags waving, and a fistful of bottles in each hand. And so we met and had a most enjoyable afternoon running through his line of rums, getting progressively more hammered by the minute, until it was all we could do not to break into sea chanteys and do a hornpipe right there in the bar (well…I exaggerate a little for effect because I can’t let a good story pass…but only a little) — and because I really liked this one a lot, I’m going to start with it to give an introduction to the company, the man and the rum

Since Calgary is known for its maritime waterways, it was just a matter of time before Captain Colp sailed into my area with a blatting tantaraa of trumpets, all flags waving, and a fistful of bottles in each hand. And so we met and had a most enjoyable afternoon running through his line of rums, getting progressively more hammered by the minute, until it was all we could do not to break into sea chanteys and do a hornpipe right there in the bar (well…I exaggerate a little for effect because I can’t let a good story pass…but only a little) — and because I really liked this one a lot, I’m going to start with it to give an introduction to the company, the man and the rum

Rum Specs, Tasting Notes

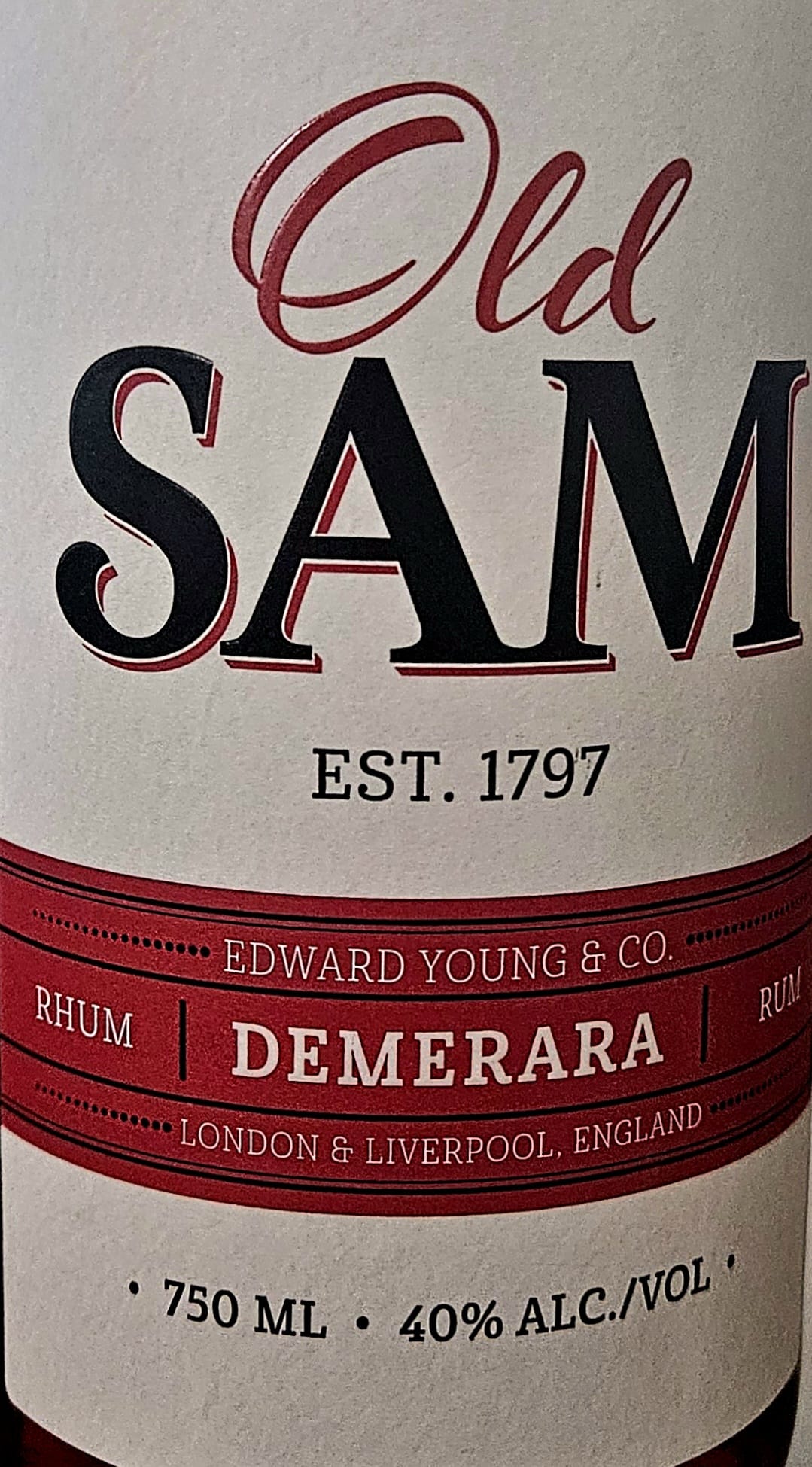

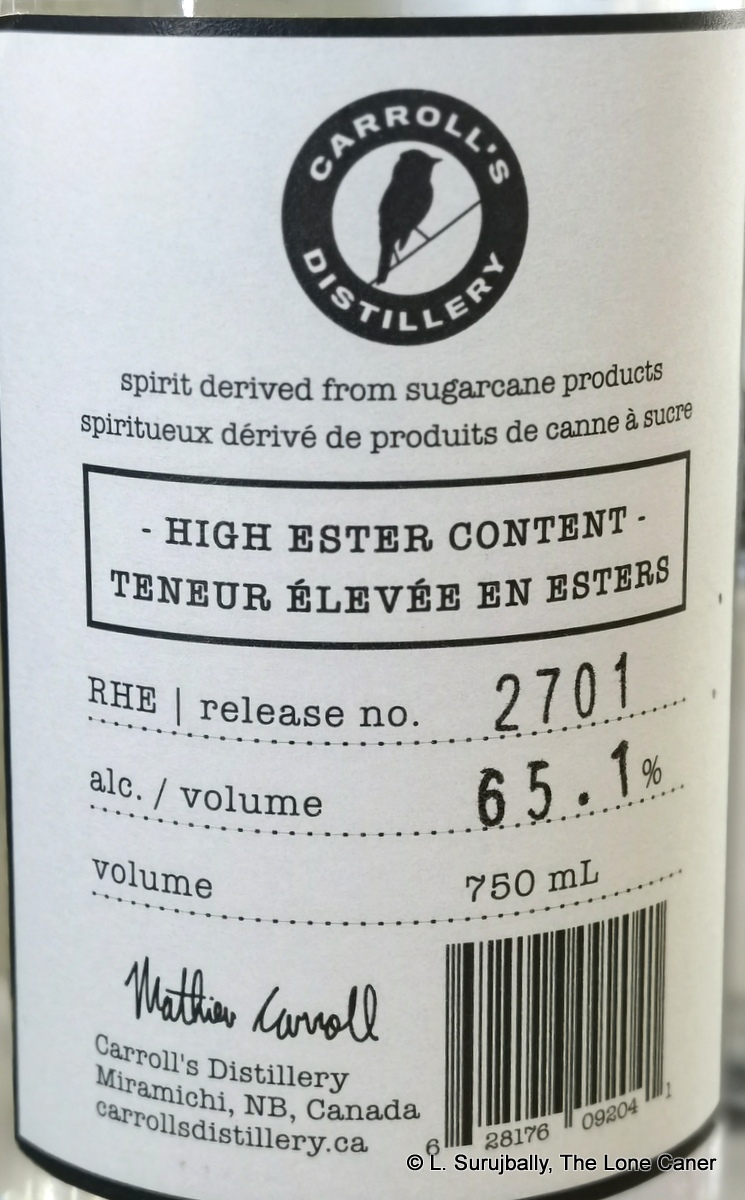

Basically this is a rum that is not quite an agricole-style, but close: cane honey in this case, or more specifically, unrefined Guatemalan and Demerara cane juice crystals (specifically not refined sugar) akin to jaggery or panela, re-liquefied, rendered down to honey, and then fermented for a few days. The distillate coming off the pot still is then aged – if the term could be used – in just about dead’r-than-a-doornail casks sourced in the Caribbean, with little to offer except maybe bad advice, for six to eight weeks: just long enough to impart a little colour, but not enough to appreciably alter the flavour profile that was (and is) desired.

Cap’n Colp is a huge proponent of letting natural flavours pop out, and some edge be retained, without too much oak influence gumming up the works. One aspect of the process that comes in for mention here is that Gregg re-distils the lees in each run, for added flavour and bite and pungency, and it is this step that I believe elevates the rum beyond the puling milquetoast vodka wannabes that populate far too much of the barren wasteland of the Canadian rum shop shelves into something really original.

“Wow!” I wrote in my initial evaluation when I smelled it – “This thing has real character!” And it does. The nose starts out with the aroma of forests and sun-dappled jungle glades steaming after a warm tropical rain: loam, wet earth, brine, mud, waterlogged bark — and believe me, this is far from unpleasant, more like a deep mossy herbal scent that channels cane rum in a fascinatingly different way. And that’s just the start – the fruits make their entrance after a while: ripe green grapes, apples, tart peaches, overripe mangoes, attended by light florals and and sweet sugar water, plus (and I know this will turn some off) ashes and dusty cardboard. I mean, the nose pretty much presses most of the buttons we would expect in an unaged or young agricole from the islands…except that this is made north of 49.

The palate is also really good, notwithstanding the living room strength with which it comes out: it tastes initially of fresh hay drying in the sunshine after a rain, as well as of honey, sugar water, sweet corn, green peas from the can… odd I’ll grant you, but far from unpleasant. Original is not a bad word to describe it, yet completely rum-like. Moreover, after a while we also get white fruits, watermelons, brine, a few Moroccan red olives, a touch of ashes and cardboard again, and just enough lemon zest to make a point without overwhelming everything. It all leads to a subtly powerful finish that sums up all of the above, without adding anything to the party – light fruits, some sour and tart notes, laban, yogurt, ashes, lemon zest and a nice filip of delicate florals.

Summing Up

Like I said, it’s a lot, and I think that as a sipping rum,it’s really nice, even if the company website suggests it’s something of a mixer’s ingredient (good for a “caipirinha, pisco sour, mojito, and even some traditionally tequila based drinks” says the website). It has that versatility of purpose that I think makes for a good rum that tyros can cut their teeth on, without alienating more experienced drinkers. It works, in short, on many levels at once.

Lest you believe this was the romanticized ravings of an over the hill reviewer who imbibed too much, and got far too high on his friend’s supply, I invite you, should you come across a bottle, to give it a try. It reminds me of some lof the experiments I tried from those new UK distilleries a year or two back – it shares much of the same sense of untamed wild madness, the desire to go where the process led and to hell with tradition. It’s a sort of analogue to writing, I think – you write what you yourself want to read and head in the direction where that leads you.

Here, Gregg Colp has experimented, added eye of newt and tail of toad into his cauldron, stirred, added some spider’s webs and his own personal brand of magic – and come up with a rum that he himself wanted to drink. And man, does it ever work, on many levels. I’m going to go right out there and buy pretty much everything else the guy makes, I’m that impressed with it. I hope you can try it yourself one day, and see if you agree.

(#1122)(86/100) ⭐⭐⭐⭐

Other notes

- Video recap link of the review

- Video recap of the distillery background

- There’s a non-rum-related story behind the photograph and the name of the rum, but the website covers enough of that and this review is already too long. It channels a typically Maritime sense of humour, tall tales of the Paul Bunyan and Pecos Bill stripe, plus a play on words that any punster would enjoy. I’ll leave you to check it out.

- The outturn is unknown. A few thousand bottles per batch, I think.

- The company is available on social media (FB, IG, YT) and their website is here.