For a country that boasts a huge population of rum-swilling West Indians and a not inconsequential number of Maritimers out east who inhale dark rums with their Jiggs Dinner, it’s odd that rums are not more appreciated and available than they are. To some extent the paucity of decent rums from abroad is alleviated by the emerging local craft distillery movement, with tasty products coming out of Ironworks, Romero, Mandakini and Potters (among several others); too, the Newfoundland Liquor Corporation makes some really interesting blends (Cabot 100 and Young’s Old Sam remain personally appreciated mixing favourites) and there’s even an Indie bottler out in BC called Bira!, run by a friend, Karl Mudzamba which fields a cask strength South Pacific and Mhoba release, with more to come.

Against all of that you have the also-rans that clutter up the store shelves in their multitudes, and which occasionally tax my objurgatory powers and genteel vocabulary to the limit: rums like Highwood’s Aged White Caribbean, Momento or the Merchant Shipping Co White, Minhas / Co-Op’s Caribbean White, all those cheap Lambs and Bacardis, and so on. There’s no shortage of low-cost fuel for the masses, yet an odd lack of serious attempts to go the Foursquare ECS route and produce a mid-level blended product of real class that can kickstart the premiumisation of Canadian rum. And yet, as the Mandakini ersatz Malabari rum proved, go even a little off the reservation, take even a bit of a chance, target the right audience…and you can sell out every release you make.

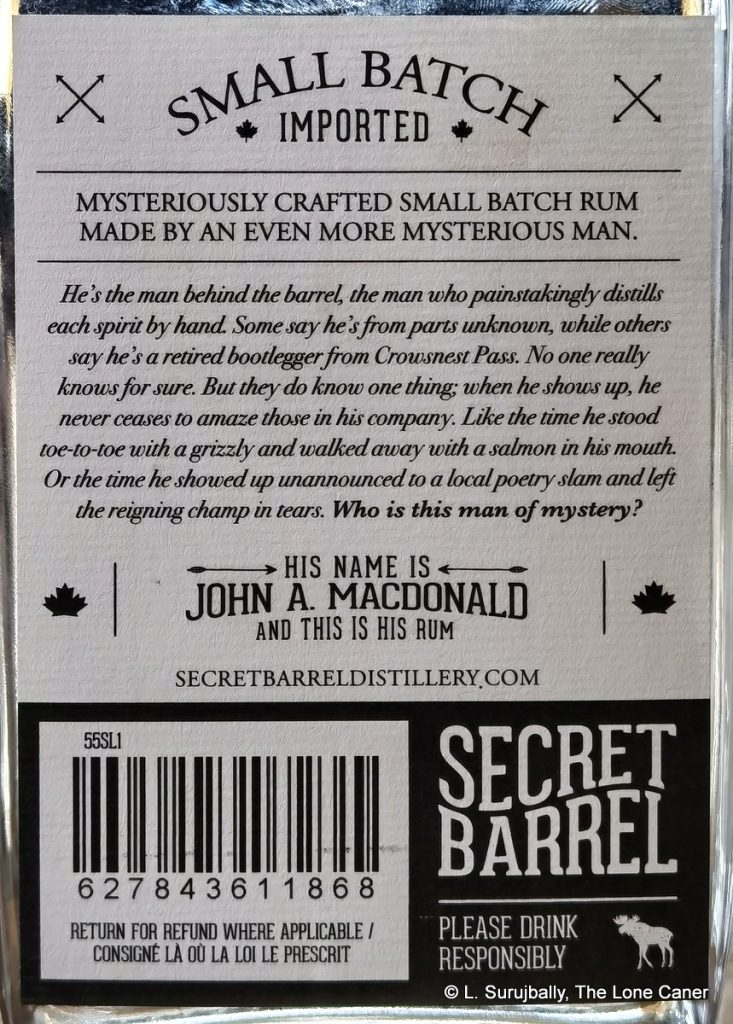

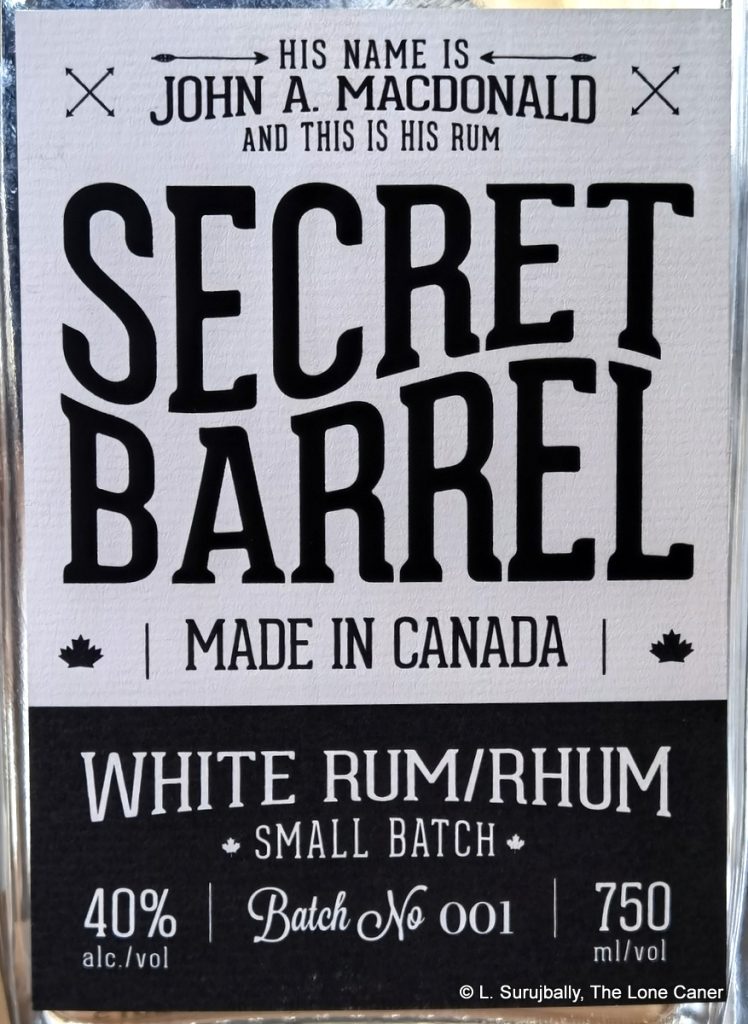

The question the overlong preamble above poses for us today, then, is whether the first release of Secret Barrel Small Batch White Rum is gold or gunk, something that gives Canadian rum brownie points…or drags it down. Now admittedly, the presentation is nifty: it channels the old square shape of turn-of-the-century whisky bottles, as does the design of the label and its font. And the narrative is amusing if nothing else: small batch, 40% and implying that maybe, possibly, it’s made in Canada (possibly in the south of Alberta, around Crowsnest Pass) by some mysterious old timer named John A. MacDonald. This is a gent who – so the back label helpfully informs us – is a cross between the Most Interesting Man in the World, and one who has exploits so off the wall that he’s obviously a relative of Chuck Norris, Pecos Bill and Paul Bunyan…all at once. On the other hand, we get nothing about a true country of origin, a true distillery, a still, source material, ageing, nothing.

The question the overlong preamble above poses for us today, then, is whether the first release of Secret Barrel Small Batch White Rum is gold or gunk, something that gives Canadian rum brownie points…or drags it down. Now admittedly, the presentation is nifty: it channels the old square shape of turn-of-the-century whisky bottles, as does the design of the label and its font. And the narrative is amusing if nothing else: small batch, 40% and implying that maybe, possibly, it’s made in Canada (possibly in the south of Alberta, around Crowsnest Pass) by some mysterious old timer named John A. MacDonald. This is a gent who – so the back label helpfully informs us – is a cross between the Most Interesting Man in the World, and one who has exploits so off the wall that he’s obviously a relative of Chuck Norris, Pecos Bill and Paul Bunyan…all at once. On the other hand, we get nothing about a true country of origin, a true distillery, a still, source material, ageing, nothing.

Well, tasting blind sharpens the senses, I tell myself, so knowing the rum is standard strength, I waste no time, pour a glass and move on to how it performs. Nose first: faint nail polish and the light fruitiness of pears, papaya and watermelon start things off. It’s easy smelling, and way too light and pretty much in the wheelhouse of every bartender’s filtered white mixing rum. I expect more, somehow because although it starts off well, it fades really fast and soon it becomes more like a vodka than a rum, or some kind of mildly sweetish cough syrup. Additionally there is vanilla, some sugar water, cucumbers in rice vinegar, a bit of tinned syrup minus the fruits, and there you have it.

That taste is somewhat of a let down, to be honest, because the nose suggested there would be something there to enthuse, a bit of tart fruitiness maybe, some sweetness and edge, maybe a lone ester or two. Alas, no. One senses some sugar water and vanilla, a bit of overripe apple, a touch of brine, cucumber slices in alcohol, not a whole lot else; and adding water doesn’t do anything, least of all tease out more. The finish is, at best, quick and lacklustre with vague hints of acetone, alcohol and sugar water, and so clearly it’s not a taster’s rum: and while two decades ago this might have been a great mixer, these days it fails when matched against the stronger and more distinct overproof cocktail rums many other distilleries are making.

So what’s the background? I mean, it’s surprising how little information there is about the thing and in this day and age no commercially made rum should deliberately chose to be so anonymous without having a serious quality behind it. The SMWS can get away with some of this mystery, but they’re in their own zone and do a decent job of it. Not so here.

However, I have managed to find out that the Secret Barrel is a Guyanese rum imported from down south (but not from where you think). It’s been aged a little, about a year or two, and imported as is, then bottled by Highwood Distillery in Alberta, though they themselves had no hand in the selection process – they did so on behalf of the owners of the Secret Distilling Company (see below for more details on company background).

The whole business about John A. MacDonald is fun to read…and a cute fabrication, perhaps based on one of the founders’ relative or ancestors. Perhaps it’s just as well it’s a fireside yarn. Because although I genuinely wanted to like this rum – surely someone who had a sense of humour and a gift for tall tales would make a rum that’s just a bit off and good for raised eyebrows and a laugh or two? – it doesn’t really come up to scratch. Even with my limited experience in the world, my life is far more interesting than Old Mr. MacDonald’s, I have better tall tales and beer stories than he does, and for sure have had acquired far better rums than the one his name is on.

(#1045)(68/100) ⭐⭐

Other Notes

- Video recap is here.

A few words on the company behind this little white rumlet. According to their slightly more informative website, Secret Distilling Company was started by a bunch of Calgarians in 2015 (I dug around and found out this was Adam MacDonald (the founder and man behind it all), and his friends Aaron Norris, Brendan O’Connor and Chase Craig, who all took over different aspects of the operation). They saw a market for rum opening in Western Canada, and rather than sinking serious money into a distillery and the concomitant years of development work, they went the blender’s route and looked around for stock. They found it in Guyana, and this is why their website speaks to them selling “Demerara” rums, as well as Banks XM rums.

Now this is where it gets interesting. First of all, they never stated on the label of those Demeraras which operation supplied the rum, and most of you reading this would instantly think DDL. But it’s not. In fact, it’s from the other rum producing company in Guyana which gets far less attention, Banks DIH, who make the well regarded XM series of rums (which of course also contradicts the “Made in Canada” on the label). Secondly, in the About page they claim the rum is from the “Banks Distillery of Guyana” except that Banks is not and never has been a distillery – they’re a brewery and a rum blender, not a distillery, and have no plans to change that. But ok: let’s chalk that up to beginner’s enthusiasm and cut them some slack.

And thirdly — and this is what got me going down the rabbit hole in earnest — on the aged Demerara rum label, they added the signature of Mr. Carlton Joao, as the Blender. This is two faux pas in one, because (a) they did so without his permission and (b) he’s not a blender at all, but a marketing executive. How do I know that? Because I know the guy personally — I went to school with him in Guyana, consulted with him on the Banks company bio — and so as soon as I saw this I picked up the phone and called him and asked what was going on. He said he knew nothing at all about it; Banks sold them stock between 2015 and 2018 and they distribute the XM rum line, but that was all. The commercial relationship was pretty much over years ago.

Where their rums subsequent to 2018 come from is not mentioned anywhere, but since the original founders sold out to White Pine Resources in 2017 (this was reorganised into SBD Capital, the current owner, the following year; they invest in mining and minerals properties and for a while had alcohol and liquor sales as its prime cash generation unit), it’s possible that the Guyana route was closed down and local sources may have taken over. Gradually sales dropped, the share price of SBD dropped from three bucks a share to pennies and when I spoke to Brian Stecyk, the CEO (who was more than helpful, if understandably cagey about the affairs of the company) I got the distinct impression he’s wrapping up the show and Secret Barrel is no longer a functioning entity. In a few years the rum is likely to be a Rumaniacs entry.