On the basis of the label, you could be forgiven for thinking this rum is something of a steal at under Can$25. Proof is rated at 44.9% – unusual for white rums in this country, so that’s good. “Product of Barbados” – nice, sure to excite interest. Clear white – intriguing. Is there hope for us here?

Nope.

This is where details and knowing what to look for, matter. What is the source of the distillate (juice or molasses – best not to assume)? Is it aged or unaged (not an unusual question even for whites), and if aged, how long, where, and in what? Which distillery on Barbados made it? On what kind of still? You see how this all adds up to even more questions, and no answers. We’re not actually given anything that matters, even on the company website, and for sure not on the bottle.

Let me save you some trouble: this information is not publicly available. And it’s entirely possible that it’s a matter of indifference, intentional oversight and/or wilful ignorance (“the masses will buy what we sell regardless”). Because the cynic in me can’t shake the belief that the production info is withheld so as not to draw attention to the fact that the rum is basically crap.

No, really. The mediocrity so proudly displayed here is breathtaking. Consider a three hour tasting, summarized:

I always start with the nose, of course, but there there is hardly one of mention. There’s some sweetness, lots of ethanol fumes, a fart of icing-sugar-dusted pastry, and more paint stripper and plastic than can possibly be healthy. And all of it is contained an mishmash of melded aromas that clash and bite at each other so incessantly that it defeats even a schnozz as agile as my own.

I always start with the nose, of course, but there there is hardly one of mention. There’s some sweetness, lots of ethanol fumes, a fart of icing-sugar-dusted pastry, and more paint stripper and plastic than can possibly be healthy. And all of it is contained an mishmash of melded aromas that clash and bite at each other so incessantly that it defeats even a schnozz as agile as my own.

Oh and it doesn’t stop there. Tasting it makes me wonder why they didn’t just bottle pure ethanol and dilute it down to the required strength, because there’s so little on display, that it involves doing nothing, feeling nothing, on the way to nowhere. If it tastes of anything, it’s of vanilla, water mixed with white sugar, alcohol and….well, that’s it. No spices, no fruits, no flowers, pastries, cardboard, wood, nothing. By the time I got to this point I would have been happy with the gangrenous meat profile of a badly made TECA mixed with a lethal dose of paint thinner, but…there was nada. Nichevo. Rien. Nichts.

And a finish? [Insert snort of derision] What finish? Oh you mean the one where some scrawny ethanol note coats the back of your throat like a swamp miasma and stays there pretending to be something? Yeah, there’s that, I suppose.

On the basis of my tasting and testing and some little bit of experience, I can say it’s probably from WIRD – Mount Gay distillate would be more expensive, St. Nicks is too small and doesn’t do bulk, and Richard Seale of Foursquare told me he refused to sell to Minhas because the price they offered was too low. My real fear is that it’s only part Barbados, and judiciously mixed in with some neutral spirit from the Wisconsin distillery Minhas owns. No way to know, really. Also, it’s probably a column still product, and aged very lightly, and then filtered like a boss, which I think is a reasonable conclusion given its blandness – everything resembling character has been stripped away. I can only shake my head.

Rums like this make me despair, for, what hope is there when products so bland can be made, and, worse, be bought? Hebrews 11:1 talks about faith being “the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen”. This travesty has neither the substance to excite faith (let alone hope), nor evidence of anything except the desire to make money. The Corsairs white rum belongs to that subclass of cheap tipple which, if you have the slightest interest in drinking decent liquor, should be left where it is, or, in a just world, be poured down the drain.

(#1110)(60/100) ⭐

Other notes

Opinion

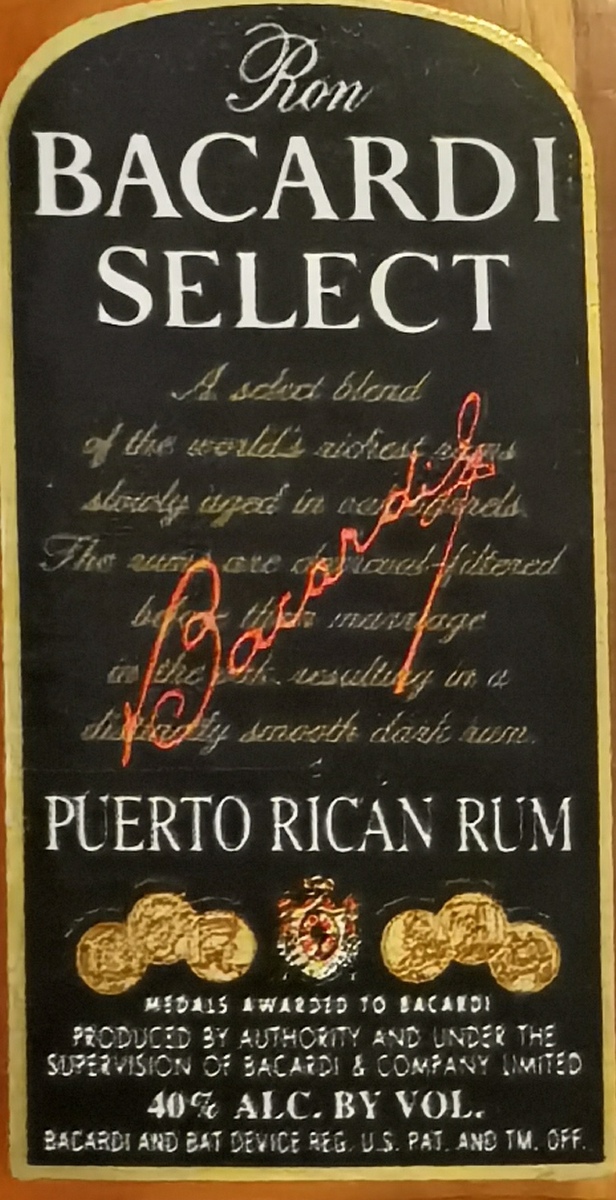

This rum is a poster child for why I regard many white rums that dot the rum landscape (and not just in Canada) with such disdain. Look no further than rums like Highwood’s Aged White Caribbean, their Momento Rum, Bayou’s white, the Merchant Shipping Co White, Minhas / Co-Op’s Caribbean White Rum, or, this one. They are all made with such indifference, such cynicism. They makes Bacardi Superior seem like a positively top-of-the-line white in comparison.

Now before you call me an elitist snob who drinks nothing but high end expensive rums, has no truck with the average rummie and who has no handle on the pulse of the budget-conscious working-class proles out there, let me explain. Such rums are, yes, dirt cheap; and they give you the alcohol shot which you can chuck into your mix and reliably get hammered – that’s part of their schtick and selling point. The argument is always made that “we make what sells” but think about it – if you sell only what you make, well, then, of course that’s what’s going to sell…the consumer has no real choice. Anyway, I argue that it’s a race to the bottom that serves no useful purpose even if all you want to do is get loaded on a slim or nonexistent budget (and on occasion, I do so myself, trust me, so yeah, I get it). If that’s all you’re after, why even bother? – getting an even cheaper vodka works just as well.

The problem with these anonymous, androgynous, monotonous and tedious taste-lacking cocktail fodders is that to all intents and purposes they are faux-vodkas — so what’s the point of sullying the reputation of a drink that has such incredible variety and taste profiles with something so indifferent? Especially when you have companies like Carroll’s or Romero out there, who are bending over backward to make decent and unique products, but remain all but unknown.

Moreover, if this is all we can afford – whether we are young and near destitute students or minimum wage worker bees struggling to make rent – well, then our entire conception of what rum is, is damaged and sullied by such stuff, and we turn away, shift to vodkas or spiced rums or whiskies, and never learn until much later that there is an amazing cornucopia of experiences out there which we have denied ourselves.

So, I’m just sayin’…. There’s better out there, white or brown. Go out there and look for it and leave this embarrassment on the shelf to gather dust and traumatize innocent itinerant reviewers, who have to try it so you don’t have to.

Company Bio (from R-0984)

Minhas is a medium-sized liquor conglomerate based on Calgary, and was founded in 1999 by Manjit Minhas and her brother Ravinder. She was 19 at the time, trained in the oil and gas industry as an engineer and had to sell her car to raise finance to buy the brewery, as they were turned down by traditional sources of capital (apparently their father, who since 1993 had run a chain of liquor stores across Alberta, would not or could not provide financing).

The initial purchase was the distillery and brewery in Wisconsin, and the company was first called Mountain Crest Liquors Inc. Its stated mission was to “create recipes and market high quality premium liquor and sell them at a discounted price in Alberta.” This enterprise proved so successful that a brewery in Calgary was bought in 2002 and currently the company consists of the Minhas Micro Brewery in Calgary (it now has distillation apparatus as well), and the brewery, distillery and winery in Wisconsin.

What is key about the company is that they are a full service provider. They have some ninety different brands of beers, spirits, liqueurs and wines, and the company produces brands such as Boxer’s beers, Punjabi rye whiskey, Polo Club Gin, and also does tequila, cider, hard lemonades. More importantly for this review, Minhas acts as a producer of private labels for Canadian and US chains as diverse as “Costco, Trader Joe’s, Walgreens, Aldi’s, Tesco/Fresh & Easy, Kum & Go, Superstore/Loblaws, Liquor Depot/Liquor Barn” (from their website). As a bespoke maker of liquors for third parties, Minhas caters to the middle and low end of the spirits market, and beer remains one of their top sellers, with sales across Canada, most of the USA, and around the world. So far, they have yet to break into the premium market for rums.

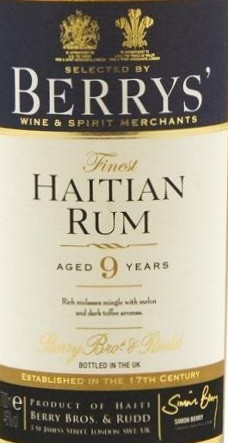

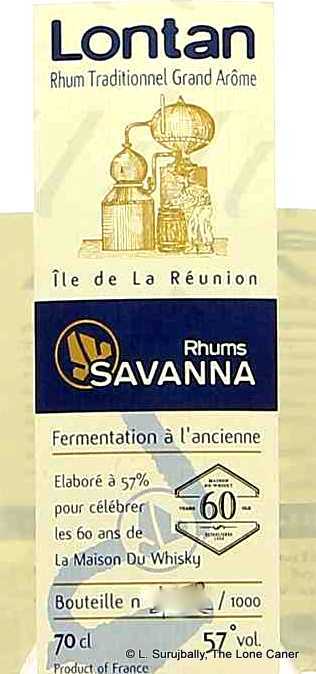

Still, this 57% ABV grand arôme, which was released in 2016 for La Maison Du Whisky’s 60th Anniversary (they went into partnership with Velier the following year and formed LM&V), seemed at pains to make the point yet again. In this case, it clearly wanted to channel a cachaca duking it out with a DOK, for it nosed pretty much like they were having a serious disagreement: vegetables and oversweet fruits decomposing on a hot day in a market someplace tropical; herbs, wet grass, sweet pickles, hot dog relish (I know what this sounds like!); sugar water; iodine, papaya, strawberries; wax, brine and cucumbers in a light pimento-soaked vinegar. I mean, seriously, does that remind you of any rum you’ve ever tried? I both liked it and wondered where the rum was hiding.

Still, this 57% ABV grand arôme, which was released in 2016 for La Maison Du Whisky’s 60th Anniversary (they went into partnership with Velier the following year and formed LM&V), seemed at pains to make the point yet again. In this case, it clearly wanted to channel a cachaca duking it out with a DOK, for it nosed pretty much like they were having a serious disagreement: vegetables and oversweet fruits decomposing on a hot day in a market someplace tropical; herbs, wet grass, sweet pickles, hot dog relish (I know what this sounds like!); sugar water; iodine, papaya, strawberries; wax, brine and cucumbers in a light pimento-soaked vinegar. I mean, seriously, does that remind you of any rum you’ve ever tried? I both liked it and wondered where the rum was hiding. This is not the first Demerara rum that the venerable Italian indie bottler Moon Import has aged in sherry barrels: the superb

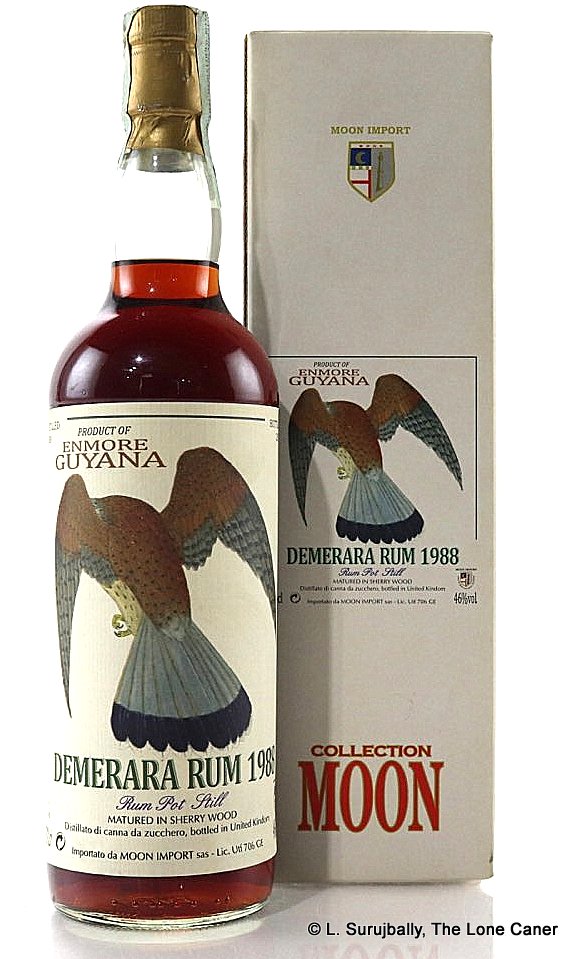

This is not the first Demerara rum that the venerable Italian indie bottler Moon Import has aged in sherry barrels: the superb

Opinion

Opinion

It gets no better when tasted. It’s very darkly sweet, liqueur-like, giving up flavours of prunes and stewed apples (again); dates; peaches in syrup, yes, more syrup, vanilla and a touch of cocoa. Honey, Cointreau, and both cloying and wispy at the same time, with a last gasp of caramel and toffee. The finish is thankfully short, sweet, thin, faint, nothing new except maybe some creme brulee. It’s a rum that, in spite of its big number and heroic Jose Marti visage screams neither quality or complexity. Mostly it yawns “boring!”

It gets no better when tasted. It’s very darkly sweet, liqueur-like, giving up flavours of prunes and stewed apples (again); dates; peaches in syrup, yes, more syrup, vanilla and a touch of cocoa. Honey, Cointreau, and both cloying and wispy at the same time, with a last gasp of caramel and toffee. The finish is thankfully short, sweet, thin, faint, nothing new except maybe some creme brulee. It’s a rum that, in spite of its big number and heroic Jose Marti visage screams neither quality or complexity. Mostly it yawns “boring!”