The other day I did a Rumaniacs retrospective on Edward Young & Co. Blue Mountain Old Liqueur Jamaican Rum dating back to the 1940s, made by an outfit founded in 1797. In doing the usual background research I found that one of my favourite low rent Canadian rums – the Youngs Old Sam – was originally made by the same company, and the current iteration’s label more references this connection more concretely than the original did.

The other day I did a Rumaniacs retrospective on Edward Young & Co. Blue Mountain Old Liqueur Jamaican Rum dating back to the 1940s, made by an outfit founded in 1797. In doing the usual background research I found that one of my favourite low rent Canadian rums – the Youngs Old Sam – was originally made by the same company, and the current iteration’s label more references this connection more concretely than the original did.

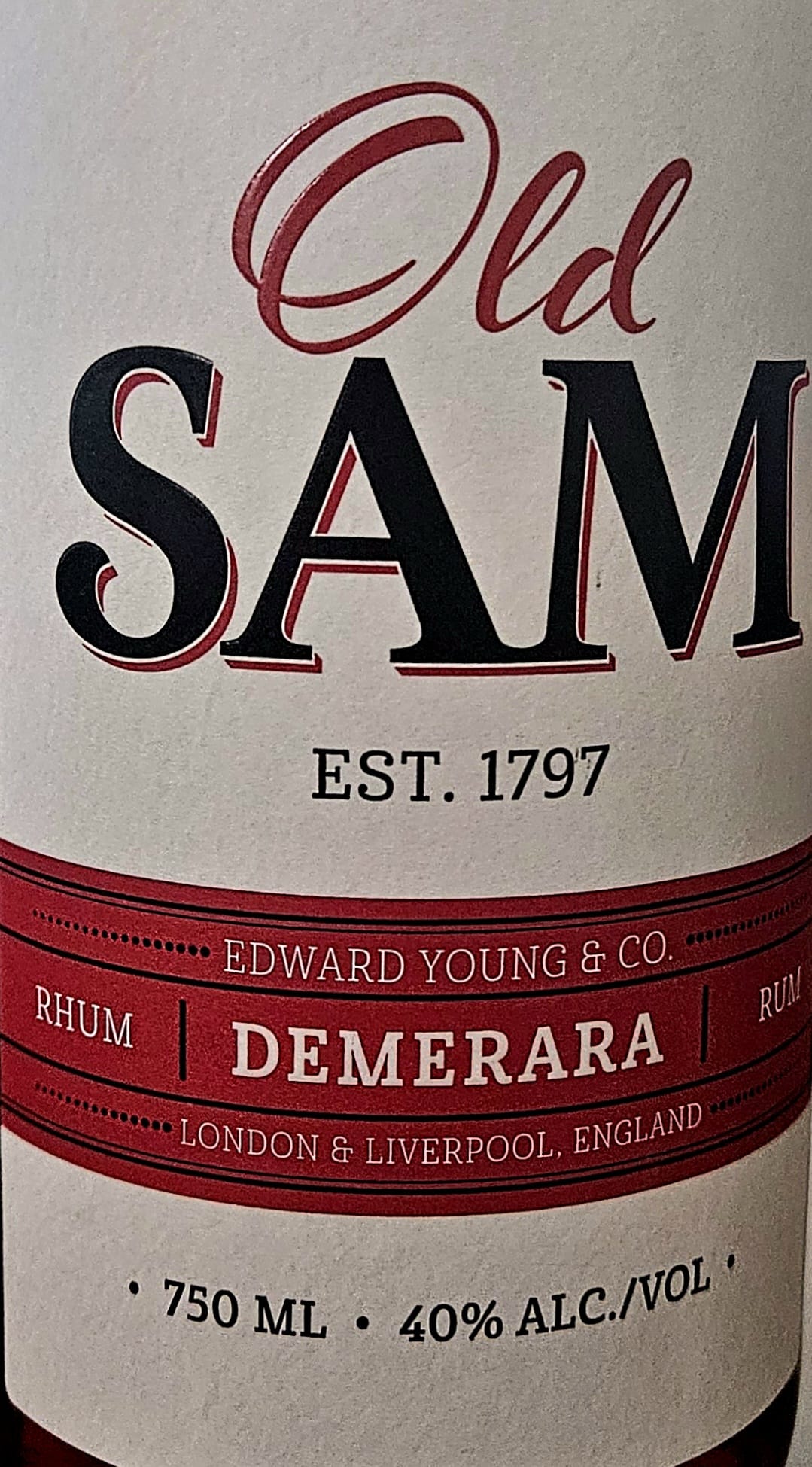

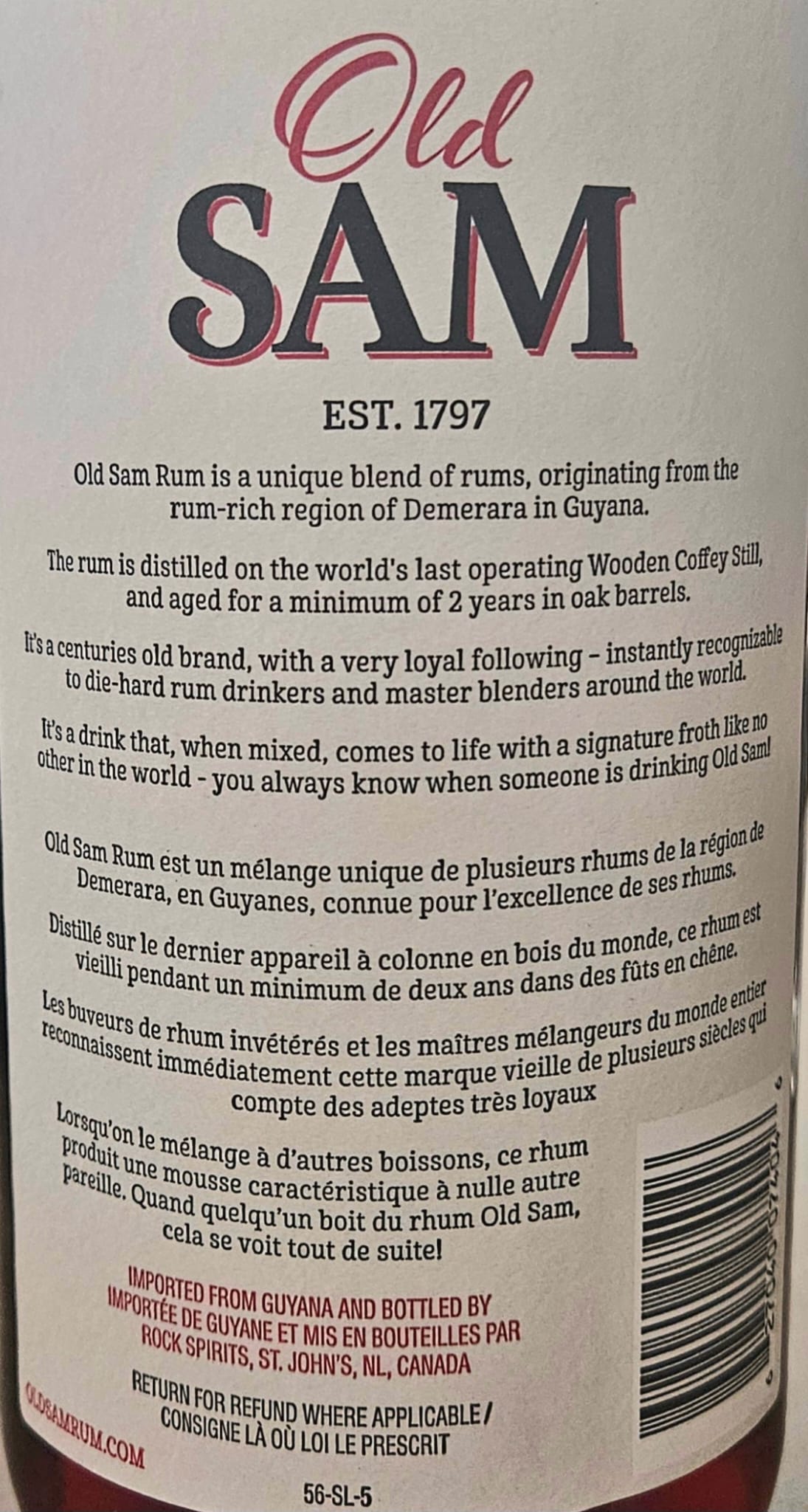

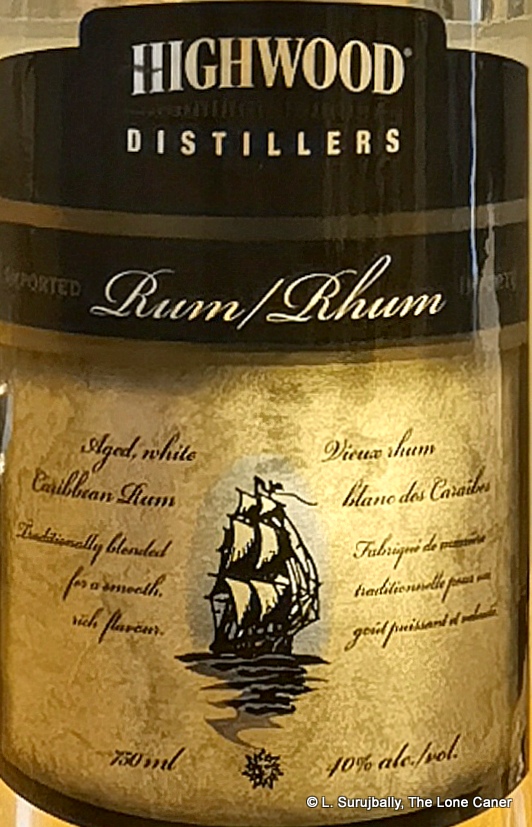

That said, the pickings remain oddly thin. According to those sources I checked, the Newfoundland & Labrador Liquor Corporation (NLLC) picked up the brand in 1999 and have marketed it it as Young’s Old Sam ever since – until, that is, in 2021, when — with increased social consciousness arising from the BLM movement — the stylized drawing of a man on the original yellow label came under fire for being racially insensitive, and was promptly removed…although why they bothered is a mystery, since the “Old Sam 5” has the same drawing on it to this day. Anyway, the current label of this bottle has no graphics of any kind, just text: it says it’s “Old Sam Demerara Rum” (they dropped the “Young” for some reason, and I wonder, do they have permission to use the term “Demerara Rum”?) with additional text stating “Edward Young & Co, London and Liverpool, England.”

But when all is said and done, it’s a blended Guyanese rum aged for 1-2 years, with distillate wholly or partly from the Enmore coffey still, and is bottled at 40%. For now I’ll accept it was aged in Guyana, if only because the NLLC website makes no mention of warehousing and ageing facilities of its own. The rum, by the way, is also quite dark, which means that it’s been coloured to conform to some non-knowledgeable dweeb’s perception that Demerara rums should be deep brown, or to pretend it’s aged more than it has been.

It noses very much like a Demerara rum, and has all the usual notes one would expect where some wooden still action is doing the tango. Initially the deep scents are of coffee grounds, plums, licorice, brown sugar, and cinnamon. Then, after letting it stand for a bit you can smell some bitter chocolate and well polished leather, and later still there are hints of burnt (yes, burnt) pastries, toffee, caramel, red wine and vinegar. But no real wooden still notes of the kind I would have expected from the Enmore still, not really. Certainly nothing along the line of pencil shavings, wet sawdust or freshly sawn timber.

It noses very much like a Demerara rum, and has all the usual notes one would expect where some wooden still action is doing the tango. Initially the deep scents are of coffee grounds, plums, licorice, brown sugar, and cinnamon. Then, after letting it stand for a bit you can smell some bitter chocolate and well polished leather, and later still there are hints of burnt (yes, burnt) pastries, toffee, caramel, red wine and vinegar. But no real wooden still notes of the kind I would have expected from the Enmore still, not really. Certainly nothing along the line of pencil shavings, wet sawdust or freshly sawn timber.

The palate is less in all ways. It’s rather thin, and scratches bitchily at the tongue as if wanting nothing better than to be gone (and it is). It’s a touch salty, has dark fruits, raisins, figs and sweet soya notes. Perhaps with some effort you can find the coffee grounds and unsweetened chocolate again, but overall, it’s just a bunch of scrawny but familiar flavours, held together with string, bailing wire and duct tape. It’s not a sipping rum by any means, as the hasty scramble for the exit demonstrated by the lacklustre finish amply demonstrates – it vanishes fast, with just the faint memory of dates, coffee, sweet soya and vanilla left behind (and that not for long).

All right, so perhaps that’s a bit snarky of me too. After all, it’s a low-priced young rum that is made to be put into a Cuba libre or whatever, and at that it does a decent job. And it does have some nice flavours for those who are (like me) somewhat enamoured of the Demerara style rum profiles. But I have to say that it seems a bit too confected to take at face value, and the taste doesn’t really live up to what the nose implies. The original unscored review I wrote was mildly positive about it (admittedly I was somewhat wet behind the ears at the time), but a decade and a half later I can’t really say that it should rate above 80 points, with the caveat that if you are more into cocktails, you might want to bump it up a notch. That’s about as fair as I can be about it.

(#1099)(78/100) ⭐⭐⭐

- Video Recap is here.

- The rum tests out at 38.8% ABV, which indicates something else (~8 g/L) is in there besides the rum. That might account for the thick smoothness the nose suggests.

- The back label says the rum is a “unique blend of rums…distilled on the world’s last operating Wooden Coffey Still…aged for a minimum of two years in oak barrels.” We need to unpack that brief declaration. For one, the company’s own website says that the blend includes “one of the marques […] produced…on the world’s last operating wooden coffee still” (sic) (while the label implies it’s all from that still); and specifically mentions that it’s aged for at least fifteen months, not two years, thought it adds that ageing is done in Guyana. Given that of late I have heard DDL is no longer exporting bulk rum from the heritage stills, one wonders if this situation can continue – though it is likely that for long term favoured clients, the rules may be bent.

Company Bio (summary)

Rock Spirits is the manufacturing arm of the NLLC which is a provincial crown corporation (effectively a government liquor monopoly, like the LCBO in Ontario) and is the only such corporation with its own manufacturing and bottling division. It was founded in 1954 and currently owns some fifteen brands sold across Canada, including rums like Screech, Cabot Tower, London Dock, George Street, Ragged Rock. Almost all of these are from Guyanese stocks, which implies a long standing relationship with DDL.

They also have partnership agreements with other brands, which is why Smuggler’s Cove Rum from Glenora Spirits in Nova Scotia is apparently made in Newfoundland (and this makes sense since they don’t list it, or any other rum, on their own website, as they rather embarrassedly did back in 2010 when I first looked in on them). While it’s not stated outright anywhere, it’s likely that they provide blending services and bottling runs for other companies as well.

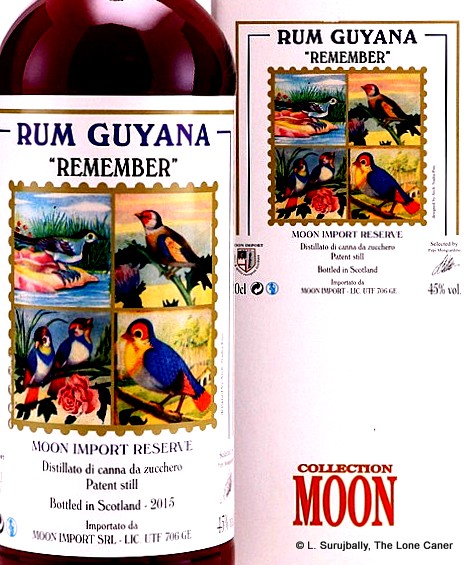

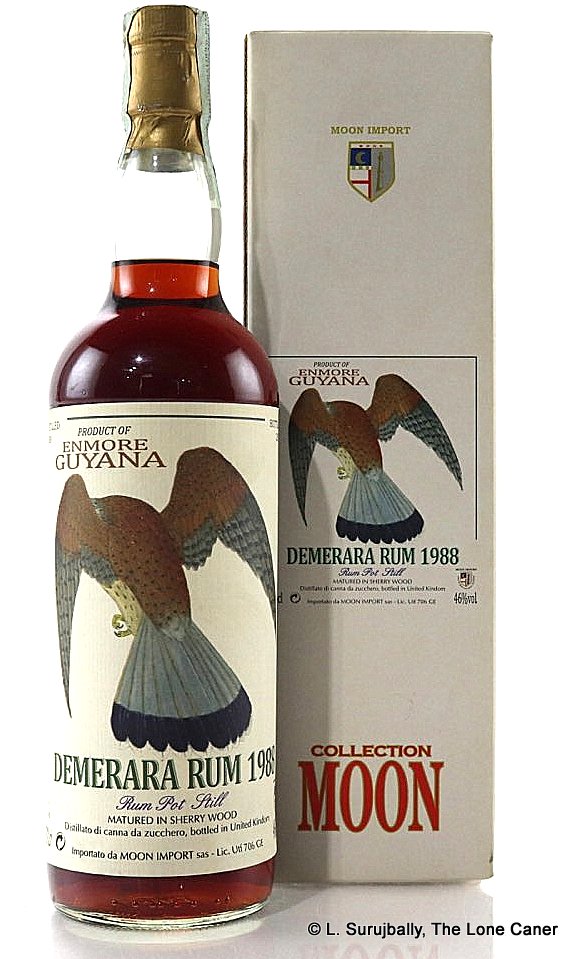

This is not the first Demerara rum that the venerable Italian indie bottler Moon Import has aged in sherry barrels: the superb

This is not the first Demerara rum that the venerable Italian indie bottler Moon Import has aged in sherry barrels: the superb

Opinion

Opinion

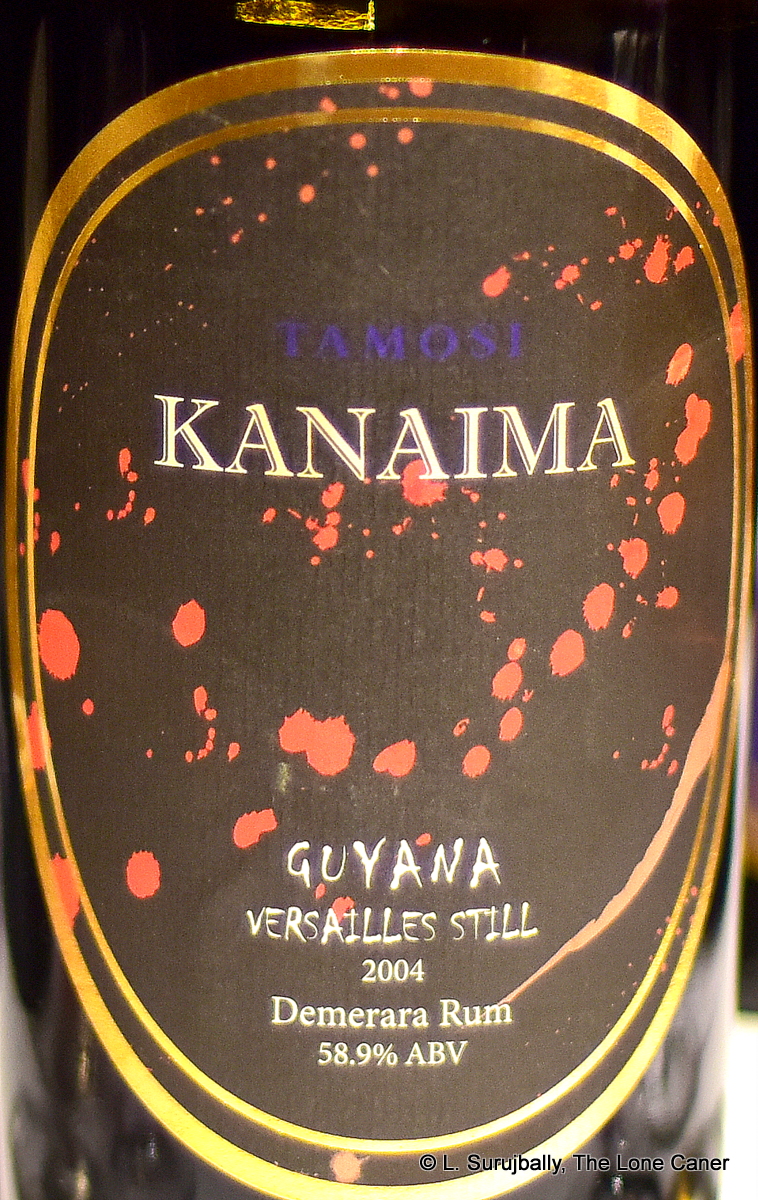

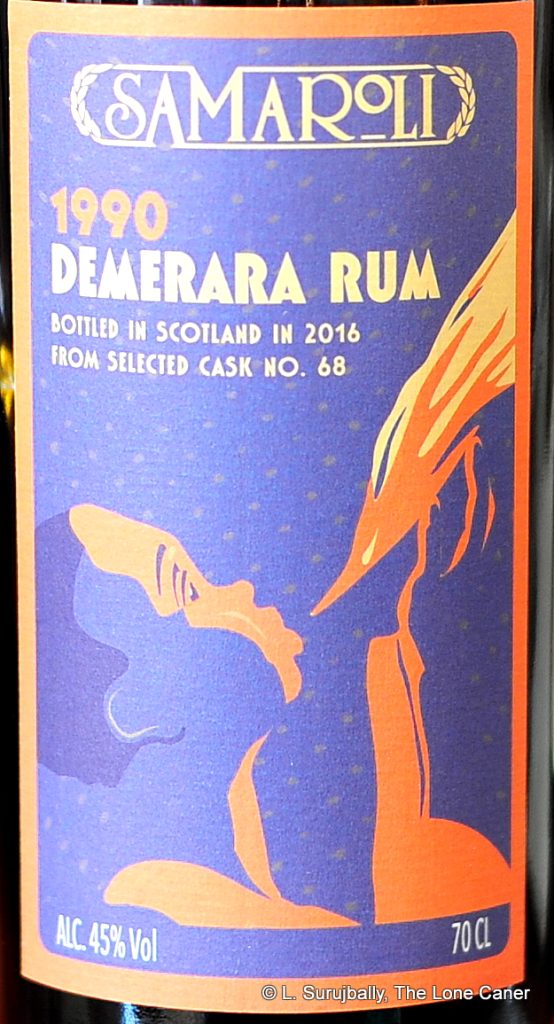

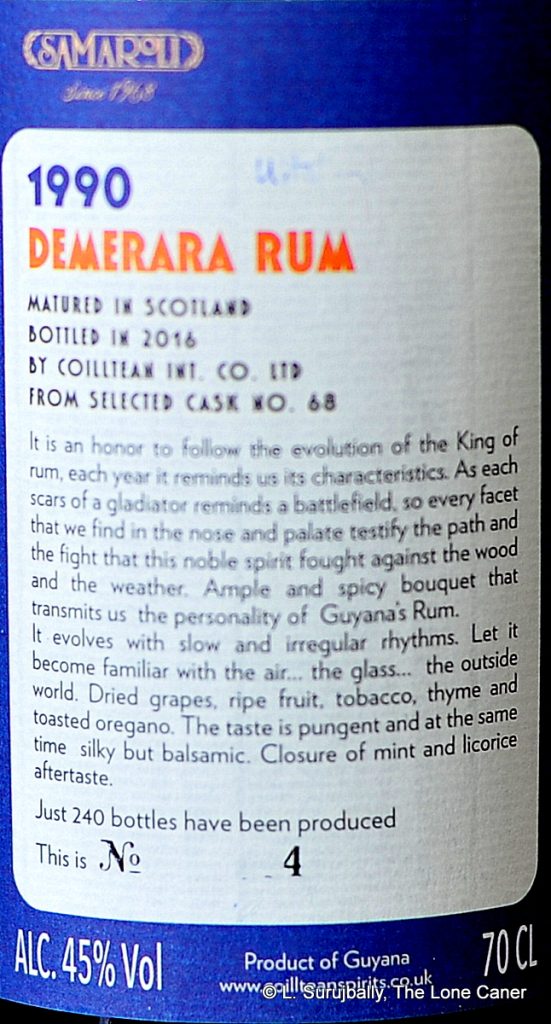

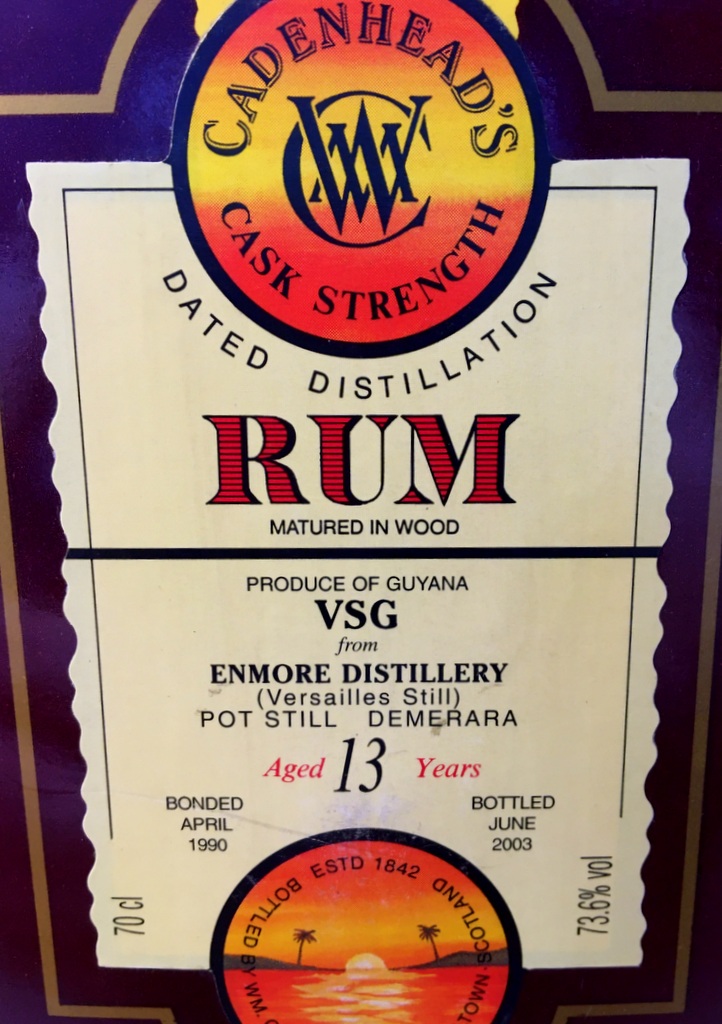

I do, on the other hand, like the taste. It’s warm and rich and the Enmore still profile – freshly sawn lumber, sawdust, pencil shavings – is clear. Also sour cream, eggnog, and bags of dried, dark fruits (raisins, prunes, dried plums) mix it up with a nice touch of sandalwood. It takes its own sweet time getting the the point and is a little discombobulated throughout, but I can’t argue with the stewed apples, dried orange peel, ripe red guavas and licorice – it’s nice. The finish is quite solid, if unexceptional: it lasts a fair bit, and you’re left with closing notes of licorice, oak chips, vanilla, dried fruit and black cake.

I do, on the other hand, like the taste. It’s warm and rich and the Enmore still profile – freshly sawn lumber, sawdust, pencil shavings – is clear. Also sour cream, eggnog, and bags of dried, dark fruits (raisins, prunes, dried plums) mix it up with a nice touch of sandalwood. It takes its own sweet time getting the the point and is a little discombobulated throughout, but I can’t argue with the stewed apples, dried orange peel, ripe red guavas and licorice – it’s nice. The finish is quite solid, if unexceptional: it lasts a fair bit, and you’re left with closing notes of licorice, oak chips, vanilla, dried fruit and black cake.

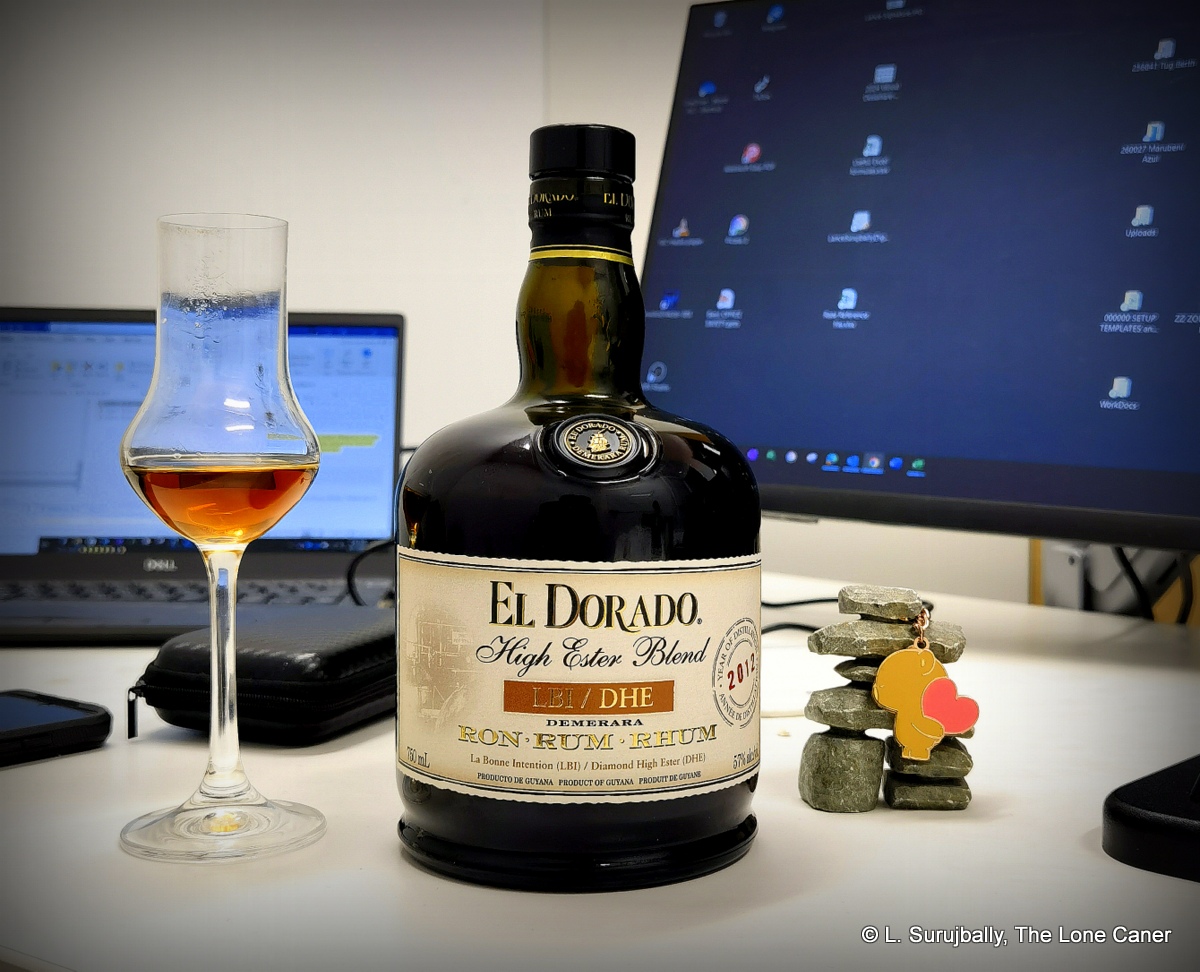

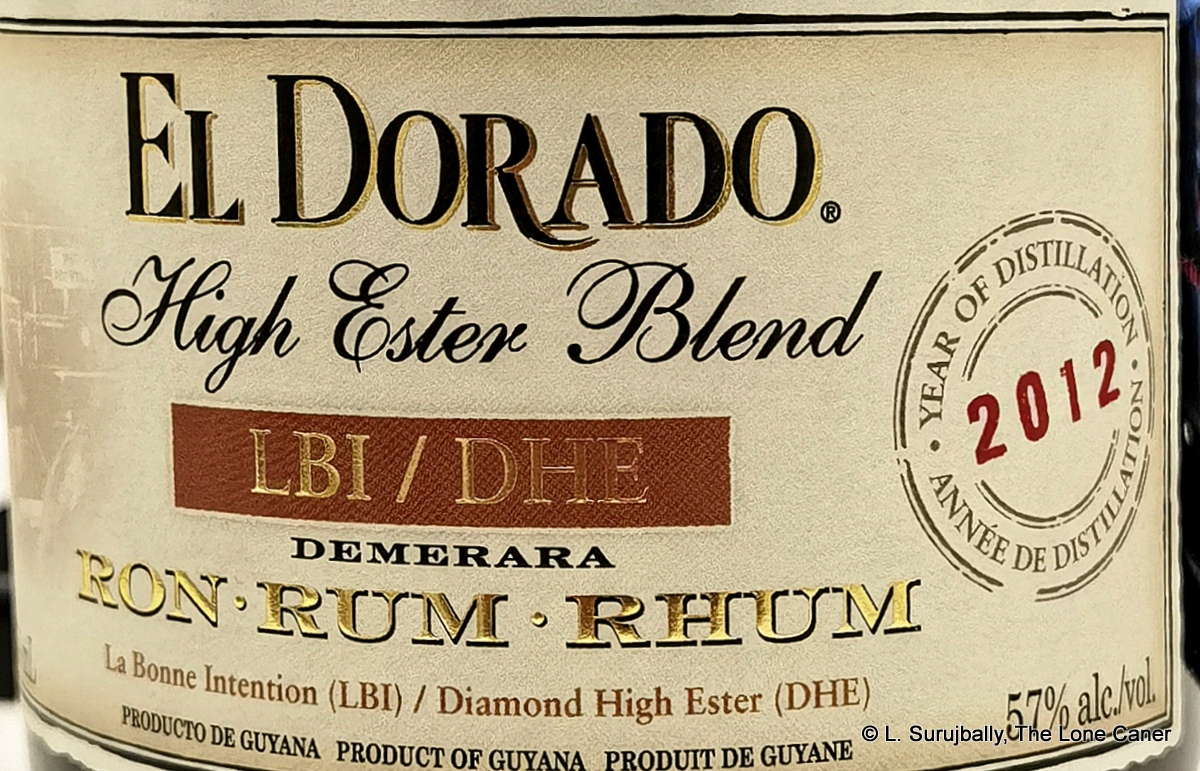

By the time this rum was released in 2014, things were already slowing down for Velier in its ability to select original, unusual and amazing rums from DDLs warehouses, and of course it’s common knowledge now that 2014 was in fact the last year they did so. The previous chairman, Yesu Persaud, had retired that year and the arrangement with Velier was discontinued as DDL’s new Rare Collection was issued (in early 2016) to supplant them.

By the time this rum was released in 2014, things were already slowing down for Velier in its ability to select original, unusual and amazing rums from DDLs warehouses, and of course it’s common knowledge now that 2014 was in fact the last year they did so. The previous chairman, Yesu Persaud, had retired that year and the arrangement with Velier was discontinued as DDL’s new Rare Collection was issued (in early 2016) to supplant them. The nose had been so stuffed with stuff (so to speak) that the palate had a hard time keeping up. The strength was excellent for what it was, powerful without sharpness, firm without bite. But the whole presented as somewhat more bitter than expected, with the taste of oak chips, of cinchona bark, or the antimalarial pills I had dosed on for my working years in the bush. Thankfully this receded, and gave ground to cumin, coffee, dark chocolate, coca cola, bags of licorice (of course), prunes and burnt sugar (and I

The nose had been so stuffed with stuff (so to speak) that the palate had a hard time keeping up. The strength was excellent for what it was, powerful without sharpness, firm without bite. But the whole presented as somewhat more bitter than expected, with the taste of oak chips, of cinchona bark, or the antimalarial pills I had dosed on for my working years in the bush. Thankfully this receded, and gave ground to cumin, coffee, dark chocolate, coca cola, bags of licorice (of course), prunes and burnt sugar (and I

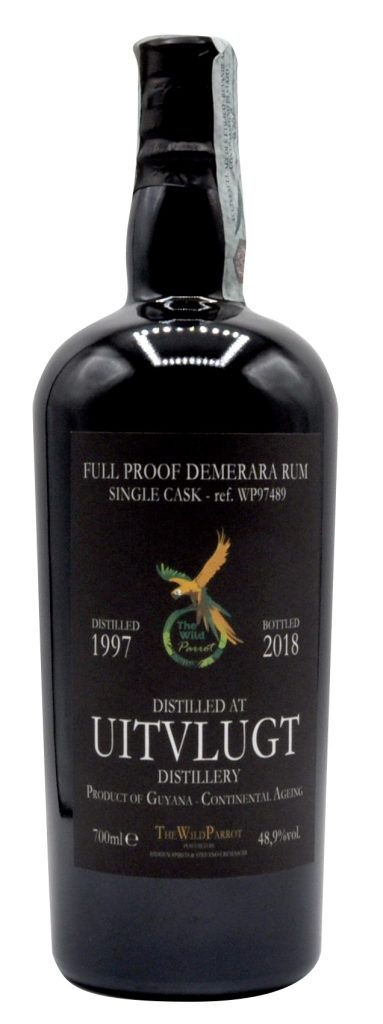

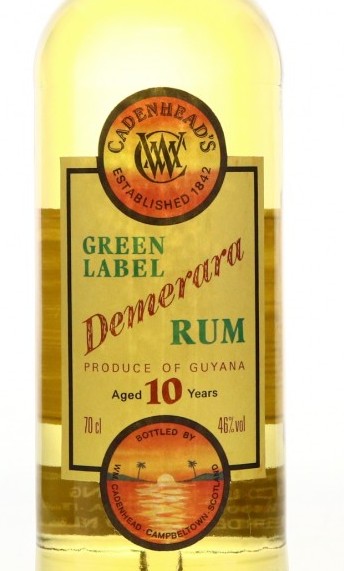

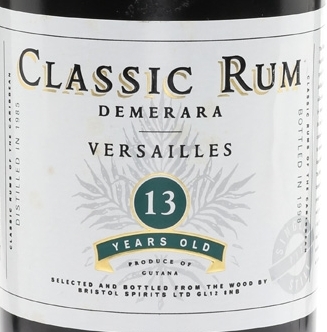

Bristol, I think, came pretty close with this relatively soft 46% Demerara. The easier strength may have been the right decision because it calmed down what would otherwise have been quite a seriously sharp and even bitter nose. That nose opened with rubber and plasticine and a hot glue gun smoking away on the freshly sanded wooden workbench. There were pencil shavings, a trace of oaky bitterness, caramel, toffee, vanilla and slowly a firm series of crisp fruity notes came to the fore: green apples, raisins, grapes, apples, pears, and then a surprisingly delicate herbal touch of thyme, mint, and basil.

Bristol, I think, came pretty close with this relatively soft 46% Demerara. The easier strength may have been the right decision because it calmed down what would otherwise have been quite a seriously sharp and even bitter nose. That nose opened with rubber and plasticine and a hot glue gun smoking away on the freshly sanded wooden workbench. There were pencil shavings, a trace of oaky bitterness, caramel, toffee, vanilla and slowly a firm series of crisp fruity notes came to the fore: green apples, raisins, grapes, apples, pears, and then a surprisingly delicate herbal touch of thyme, mint, and basil.

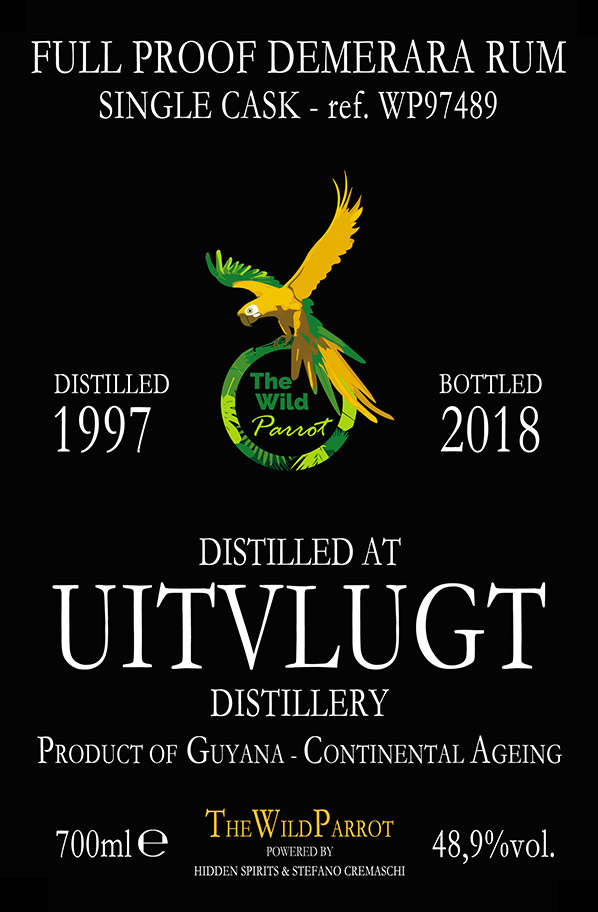

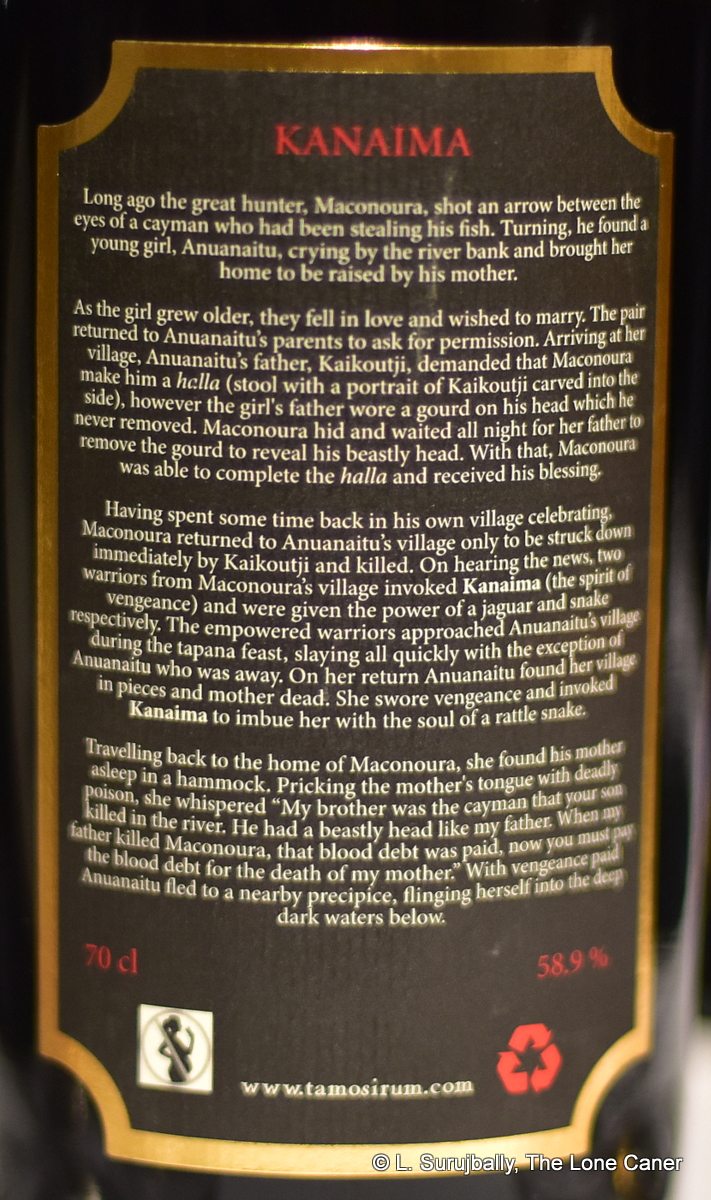

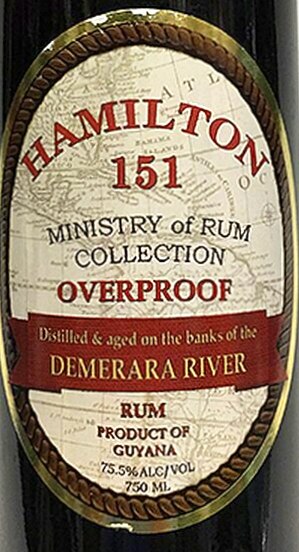

It is, in short, a powerful wooden fruit bomb, one which initially sits and broods in the glass, dark and menacing, and needs to sit and breathe for a while. Fumes of prunes, plums, blackcurrants and raspberries rise as if from a grumbling and stuttering half-dormant volcano, moderated by tarter, sharper flavours of damp, sweet, wine-infused tobacco, bitter chocolate, ginger and anise. The aromas are so deep it’s hard to believe it’s so young — the distillate is aged around five years or less in Guyana as far as I know, then shipped in bulk to the USA for bottling. But aromatic it is, to a fault.

It is, in short, a powerful wooden fruit bomb, one which initially sits and broods in the glass, dark and menacing, and needs to sit and breathe for a while. Fumes of prunes, plums, blackcurrants and raspberries rise as if from a grumbling and stuttering half-dormant volcano, moderated by tarter, sharper flavours of damp, sweet, wine-infused tobacco, bitter chocolate, ginger and anise. The aromas are so deep it’s hard to believe it’s so young — the distillate is aged around five years or less in Guyana as far as I know, then shipped in bulk to the USA for bottling. But aromatic it is, to a fault.