Recapping some background for William Hinton — it is a Madeira based distillery with antecedents as far back as 1845; at one point, in the 1920s, it was the largest sugar factory on the island if not in Europe – but in 1986 it ceased operations for two decades, 1, and was then restarted in 2006 under the name Engenho Novo da Madeira, still making branded rum under the Hinton banner. They make their own rums as well as exporting bulk elsewhere, which is how Fabio Rossi picked a few up for his Rare Rums collection back in 2017.

The company has three tiers of rum quality, with the lowest level being considered basic backbar “service” rums for mixing: there are three of these, from a 40% white we looked at in #829, a 9 months aged, and one that’s three years old. That 40% white was a flaccid agricole that could conceivably put a drinker to sleep out of simple boredom, but things get a lot more jazzed up and a whole lot more interesting with the premium or “Limited” level white (labelled as “Natural”). Neatly put, the two classes of rums generally and the two whites in particular, are night and day.

Some the stats of the two whites in the classes are the same – column still, cane juice origin…they are both agricoles. Fermented for 2-3 days with wild yeast (the other was 24 hours), and then run through that old refurbished column still that had been decommissioned (but kept) from the original estate at Funchal (Engenho do Torreão) when things shut down in 1986. And then, as if dissatisfied with this nod at tradition, they released the premium version without any ageing at all (unlike the “service” white which had been aged and then filtered back to transparency). It was also left at full strength, which is a serious attention grabbing 69%, enough to make the glass tremble, just a bit.

Some the stats of the two whites in the classes are the same – column still, cane juice origin…they are both agricoles. Fermented for 2-3 days with wild yeast (the other was 24 hours), and then run through that old refurbished column still that had been decommissioned (but kept) from the original estate at Funchal (Engenho do Torreão) when things shut down in 1986. And then, as if dissatisfied with this nod at tradition, they released the premium version without any ageing at all (unlike the “service” white which had been aged and then filtered back to transparency). It was also left at full strength, which is a serious attention grabbing 69%, enough to make the glass tremble, just a bit.

That combination of zero ageing and high strength made the Edição Limitada blanco very much like some of those savage white rums I’ve written about here and here. And that’s a good thing – too often, when a company releases two rums of the same production process but differing proofs, it’s like all they do is take the little guy, chuck it on the photocopier and pressed “enlarge”. Not here. Oh no. Here, it’s a different rum altogether.

The nose, for example, is best described as “serious” – an animal packing heat and loaded for bear: it starts with salt, brine, olives, wax, rubber, polish, and yet, the whole time it feels clear — fierce, yes, but clear nevertheless — and almost aromatic, not weighed down with too little frantically trying to do too much. A bit fruity, herbal to a fault, particularly mint, dill, sage and touch of thyme. There are some citrus notes and a warm kind of vegetal smell that suggests a spicy tom yum soup with quite a few mean-looking pimentos cruising around in it.

I particularly want to call attention to the palate, which is as good or better than that nose, because that thing happily does a tramping stomping goose step right across the tongue and delivers oodles of flavour: it’s like a sweeter version of the Paranubes, with rubber, salt, raisins and a cornucopia of almost ripe and fleshy fruits that remain hard and tart. The taste is herbal (thyme and dill again), and also sports olives, vanilla, unsweetened yoghurt, and a trace of almost apologetic mint to go with the fruity heat. The finish is excellent — long and salty, loads of spices and herbs, and a very peculiar back note of minerals and ashes. These don’t detract from it, but they are odd to notice at all and I guess they are there to remind you not to take it for granted.

I particularly want to call attention to the palate, which is as good or better than that nose, because that thing happily does a tramping stomping goose step right across the tongue and delivers oodles of flavour: it’s like a sweeter version of the Paranubes, with rubber, salt, raisins and a cornucopia of almost ripe and fleshy fruits that remain hard and tart. The taste is herbal (thyme and dill again), and also sports olives, vanilla, unsweetened yoghurt, and a trace of almost apologetic mint to go with the fruity heat. The finish is excellent — long and salty, loads of spices and herbs, and a very peculiar back note of minerals and ashes. These don’t detract from it, but they are odd to notice at all and I guess they are there to remind you not to take it for granted.

The rhum, in short, is amazing. It upends several notions of how good a white can be and for my money gives Wray & Nephew 63% White Overproof some real competition in that category and even exceeds the Rivers Royale 69% out of Grenada, though they are different in their construction and don’t taste the quite same. The flavours are hot and spicy and there’s lots of them, yet they never get in each other’s way and are well balanced, complex to a fault and good for any purpose you might wish to put it.

What this all leaves us with, then, is an agricole rhum that is powerful, herbal, floral and all round tasteful. It’s quality is in fact such a jump up from the “Service” white that I really must suggest you try the more premium rums, and this one, only after exploring the cheaper variants. Because if you do it the other way round you’ll really not want to have that much to do with the lesser parts of Hinton’s overall range. The Limitada excites that kind of admiration, and happily, it deserves every bit of it.

(#830)(86/100)

Other Notes

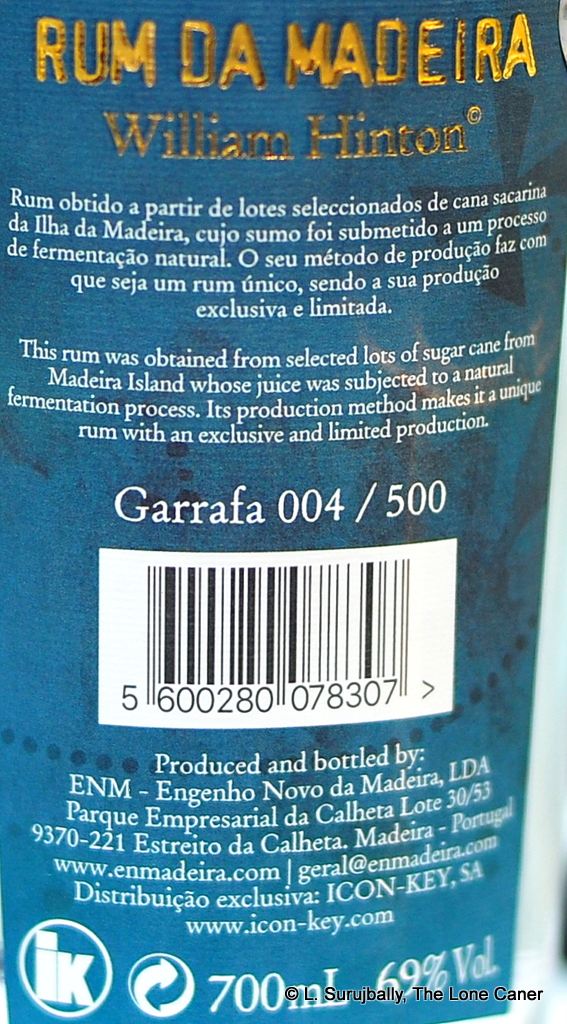

- The rum is issued in lots (or batches), by year, and all front labels tell you which one it is (here it’s Lot #1 of 2017), though not how many lots in that year. Each such batch is 500 bottles or so — hence the “Limitada” in the name — and both this and the bottle number is mentioned on the back label.