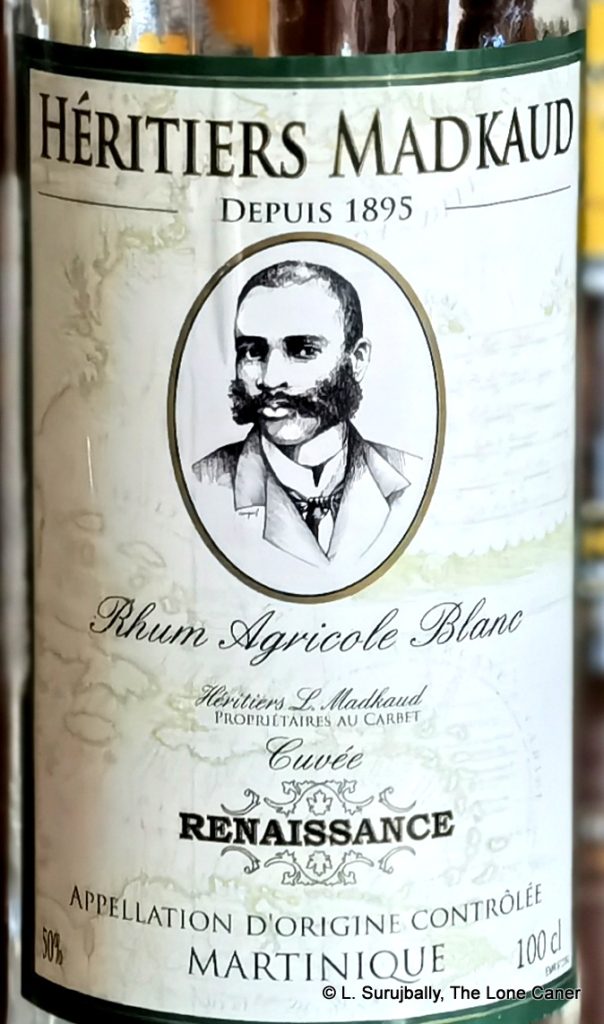

Even though it has been knocking around Europe for at least a decade, Héritiers Madkaud is not a name that will be instantly familiar to many rum aficionados…it’s probably best known to the French. They have occasionally been spotted on the festival circuit (and won a few awards), and remain easier to find in online stores than in brick and mortar shops. The rhums they release are from Martinique, are AOC certified cane juice rhums, and the blanc I tried was definitely right up there, so it’s kind of a downer that more people aren’t familiar with it

A few words about the brand, then. The basic story is that in 1893, Félicien Madkaud — the son of a freed slave from Lorraine in the north of Martinique — married the mulatto heiress of a Bordeaux merchant. Her funds gave him the capital that enabled him to buy the Fond Capot distillery in 1895 – this was part of the Duvallon estate in Carbet, then the Bellevue distillery, located near by the west-coast commune of Case Pilote. In 1906 Félicien helped his brother Augustin to open a distillery at La Dupuis in Lorrain, then he opened another for himself in Macedonia in 1920; and in 1924 he set up his nephew Louisy with La Digue distillery, which maintained production of Héritiers Madkaud rums until the mid-1970s before shuttering (the others had been closing since 1969 and La Digue was the only one left). In the early 2010s, Stéphane Madkaud, Félicien’s great-grandson, revived the brand, with distillation contracted out to Saint James in Sainte-Marie, based on – you guessed it – old family recipes.

A few words about the brand, then. The basic story is that in 1893, Félicien Madkaud — the son of a freed slave from Lorraine in the north of Martinique — married the mulatto heiress of a Bordeaux merchant. Her funds gave him the capital that enabled him to buy the Fond Capot distillery in 1895 – this was part of the Duvallon estate in Carbet, then the Bellevue distillery, located near by the west-coast commune of Case Pilote. In 1906 Félicien helped his brother Augustin to open a distillery at La Dupuis in Lorrain, then he opened another for himself in Macedonia in 1920; and in 1924 he set up his nephew Louisy with La Digue distillery, which maintained production of Héritiers Madkaud rums until the mid-1970s before shuttering (the others had been closing since 1969 and La Digue was the only one left). In the early 2010s, Stéphane Madkaud, Félicien’s great-grandson, revived the brand, with distillation contracted out to Saint James in Sainte-Marie, based on – you guessed it – old family recipes.

Currently the stable of the house has six rhums, three of which are unaged blancs: a standard white at 40% first released in 2007, a 50% edition called the Castlemore that came out in 20121; and the 50% ABV “Renaissance”, which was a 2017 special edition to commemorate 160 years of the birth of Félicien Madkaud, and for which the label changed – though I’m not sure anything else did.

Be that as it may, it is clear that the Cuvée Renaissance is staking out some new territory, because the nose starts out with such originality (this is not an unmixed blessing) that I had to look carefully at the label again to make sure I really was having an agricole. This rhum exudes a meaty, gamey, stinky aroma that induces PTSD flashbacks to the Long Pond TECA, or the Seven Seas Japanese rum…except that by some subtle alchemy it succeeds (sort of) whereas those just cheerfully traumatise. There are accompanying smells of really spoiled fruits and grapes that are flaccid and gone seriously off and yet I found myself somewhat enjoying the sheer chutzpah of the amalgam – maybe that’s because after a bit one can sense some lemon rind, lighter fruits (pears, papayas) and florals which take the bite off, balance things better, and tame the beast…although without ever entirely allowing a complete escape from the slightly rancid opening notes.

Much of this repeats when tasted. Here the 50% takes over and gives a fierceness to the profile that points up the youth and untamed nature of the rhum. Once again it starts with meat, rotting fruit and a sort of earthy taste that reminds me of an abandoned house with waterlogged drywall, an unwashed wet dog (!!) and even (get this), quinine. To its credit there are other late developing flavours that rescue it from disaster – citrus, fanta, tonic water, more light fruits and hot sweet pastries – and the finish is surprisingly well handled with musky fruity notes cut with sharper citrus and sauerkraut.

Much of this repeats when tasted. Here the 50% takes over and gives a fierceness to the profile that points up the youth and untamed nature of the rhum. Once again it starts with meat, rotting fruit and a sort of earthy taste that reminds me of an abandoned house with waterlogged drywall, an unwashed wet dog (!!) and even (get this), quinine. To its credit there are other late developing flavours that rescue it from disaster – citrus, fanta, tonic water, more light fruits and hot sweet pastries – and the finish is surprisingly well handled with musky fruity notes cut with sharper citrus and sauerkraut.

This is, admittedly, one of those rhums that will polarise opinion and even I have to concede that it does take some getting used to, and while I dislike using terms like “acquired taste,” it’s absolutely not a rhum I would recommend to neophytes. It’s a hard act to pin down because there so much weird sh*t going on at all times and after trying it four times over two days, my tasting notes are peppered with words like” amazed”, “impressed”, “fear-inducing”, “zoweee!”, “crazy” and “wtf?” You get the picture.

And yet, and yet…for all that, I believe the rhum is peculiarly excellent (I chose the term carefully), and resolutely walks its own path, with tastes that within their limits, work. If the test of any rhum you’ve not tried before is how it makes you remember it after just a single session, then something exciting the thoughts this one does is hardly a failure. That kind of originality is a rarity in this day and age of milquetoast conformity, and I agree that it’s not a rum that’s easy to love…but by God, it sure is one to respect.

(#1075)(85/100) ⭐⭐⭐½

Other notes

Whatever the case, I must advise you that if you like agricoles at all, those smaller names and lesser known establishments like Dillon should be on your radar. Not all of the rhums they make are double-digit aged, so those that are, even if farmed out to a third party, are even more worth looking at. Just smell this one, for example: it’s a fruitarian’s wet dream. In fact, the aroma almost strikes me like a very good Riesling mixing it up with a 7-up, if you could conceive of such an unlikely pairing. Lighter than the

Whatever the case, I must advise you that if you like agricoles at all, those smaller names and lesser known establishments like Dillon should be on your radar. Not all of the rhums they make are double-digit aged, so those that are, even if farmed out to a third party, are even more worth looking at. Just smell this one, for example: it’s a fruitarian’s wet dream. In fact, the aroma almost strikes me like a very good Riesling mixing it up with a 7-up, if you could conceive of such an unlikely pairing. Lighter than the

Depaz’s 45% rhum blanc agricole is not one of these uber-exclusive, limited-edition craft whites that uber-dorks are frothing over. But the quality and taste of even this standard white shows exactly how good the

Depaz’s 45% rhum blanc agricole is not one of these uber-exclusive, limited-edition craft whites that uber-dorks are frothing over. But the quality and taste of even this standard white shows exactly how good the

Tasting notes. The nose is nice. At under 50% not too much sharpness, just a good solid heat, redolent of soda, fanta, coca cola and strawberries. There’s a trace of coffee and rye bread, and also a nice fruity background of apples, green grapes, yellow mangoes and kiwi fruit. It develops well and no fault can found with the balance among these disparate elements.

Tasting notes. The nose is nice. At under 50% not too much sharpness, just a good solid heat, redolent of soda, fanta, coca cola and strawberries. There’s a trace of coffee and rye bread, and also a nice fruity background of apples, green grapes, yellow mangoes and kiwi fruit. It develops well and no fault can found with the balance among these disparate elements.

I was really and pleasantly surprised by how well it presented, to be honest. For a standard strength rhum, I expected less, but its complexity and changing character eventually won me over. Looking at others’ reviews of rhums in Reimonenq’s range I see similar flip flops of opinion running through them all. Some like one or two, some like that one more than that other one, there are those that are too dry, too sweet, too fruity (with a huge swing of opinion), and the little literature available is a mess of ups and downs.

I was really and pleasantly surprised by how well it presented, to be honest. For a standard strength rhum, I expected less, but its complexity and changing character eventually won me over. Looking at others’ reviews of rhums in Reimonenq’s range I see similar flip flops of opinion running through them all. Some like one or two, some like that one more than that other one, there are those that are too dry, too sweet, too fruity (with a huge swing of opinion), and the little literature available is a mess of ups and downs.