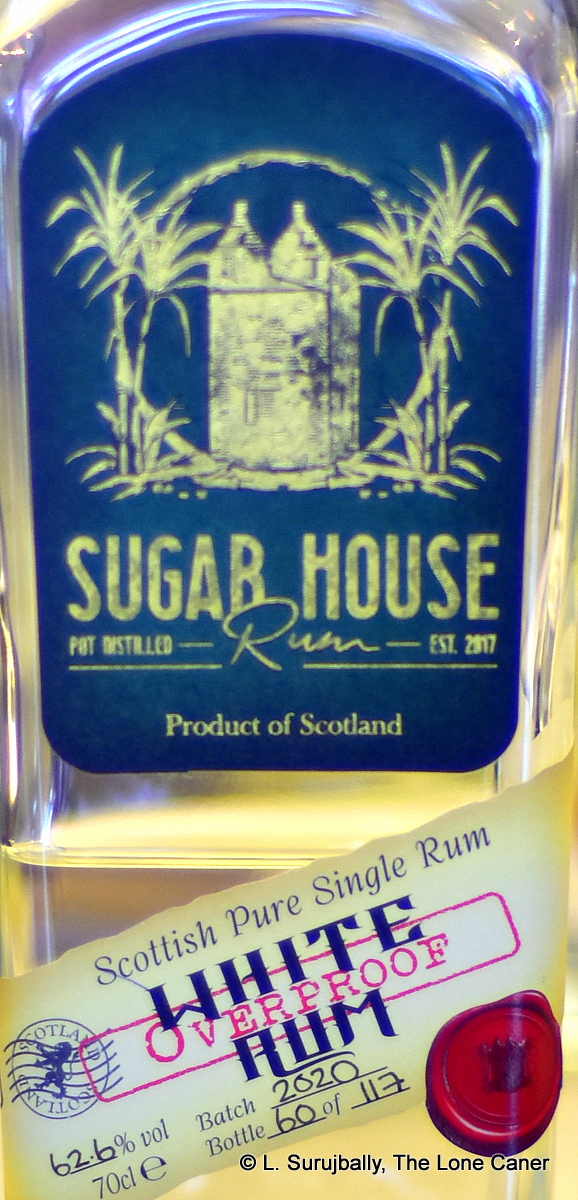

As soon as the review for the Sugar House unaged white went up, a flurry of comments resulted: “It’s not too shabby” admitted one FB denizen, “But I prefer the OP.” This was immediately seconded by another who said “Love the OP” and followed it up with a flaming icon; and right on the heels of those two remarks, another chipped in over at the NZ Rum Club, and said that yep, the OP was the sh*t there too.

I completely get that, because I have a thing for really strong rums. It’s a mixed bag, as any reader of this list can attest, but when not created with indifference to merely round out a portfolio, when made with understanding, with passion and skill, and yes, even with love (there, I said it), those snarling vulpine bastards will release your inner masochist to the point where you almost look forward to sharp pungency of their addled profiles skewering your palate.

And so when I read these quick comments, I had to hold my hands like Dr. Strangelove to stop the spoilers from coming, and from commenting that this review was already mostly written. Sugar House, one of the New Scottish distilleries (as I term them), has made three rums since they opened that excited a whole lot of attention, interest, commentary, appreciation and glass wobbling: the unaged white, the Blood Tub…and the 62.6% growler of the Overproof. No way it could be ignored.

Unleashed on the public in 2020 (that was batch #1 of 117 bottles), this was a rum deriving from wash that had fermented for four weeks (!!) using only wild yeast, was run through the pot still and pretty much left as it was. It was on display (carefully leashed, muzzled and caged for good measure) as late as 2022 when I rather thoughtlessly said “yes, sure” to Ross Bradley, the owner and distiller who was manning the innocuous Sugar House booth at the TWE Rumshow (neither of us knew who the other person was). He poured me a generous shot and stood back to, as Scotland Yard likes to say, “await developments.” (Although maybe he just wanted to be outside the spatter zone).

It’s probable that the strength was no accident, being just a hair off the Wray & Nephew White Overproof, which in turn WP is taking aim at with its own Rum Bar 63%. And when sniffed, well, it gave those legendary badasses some serious competition – it channelled such a crazed riot of rumstink that it was difficult to know where to start. Initially my increasingly illegible handwriting made mention of acetones, plastic, and a sort of sweet paint thinner (is there such a thing?). The nose was a wild smorgasbord of contrasting aromas that had no business being next to each other: salt and cardboard, rye bread liberally coated with sweet strawberry-pineapples jam…over which someone then sprinkled a liberal dose of black pepper. Fruits both spoiled and unripe, machine oil, drywall. There was a chemical, medicinal, varnish and turpentine aspect to the nose that may affront, but I stand here to tell you that it’s a terrific sets of aromas and if I had appreciated the original white rum I had started with, I really liked this one.

It’s probable that the strength was no accident, being just a hair off the Wray & Nephew White Overproof, which in turn WP is taking aim at with its own Rum Bar 63%. And when sniffed, well, it gave those legendary badasses some serious competition – it channelled such a crazed riot of rumstink that it was difficult to know where to start. Initially my increasingly illegible handwriting made mention of acetones, plastic, and a sort of sweet paint thinner (is there such a thing?). The nose was a wild smorgasbord of contrasting aromas that had no business being next to each other: salt and cardboard, rye bread liberally coated with sweet strawberry-pineapples jam…over which someone then sprinkled a liberal dose of black pepper. Fruits both spoiled and unripe, machine oil, drywall. There was a chemical, medicinal, varnish and turpentine aspect to the nose that may affront, but I stand here to tell you that it’s a terrific sets of aromas and if I had appreciated the original white rum I had started with, I really liked this one.

Did I say the smells were terrific? The palate was too, and indeed, strove mightily to surpass the nose. Here it seemed to be going in reverse gear, with the acetones, paint thinner, turps and furniture polish dialled back, and the fruits surged to the fore – big, bold, piquant, ripe, luscious, fresh stoned fruit of all kinds. And not just fruit – funk, vanilla ice cream, some oak action (odd since it’s unaged), and a deep exhalation of port infused cigarillos, damp tobacco, tanned leather and the sweat of particularly well-used three day old gym socks. Even the finish, medium long and vibrantly fresh, channelled something of this cornucopia, though you could see it was running out of steam and thankfully calmed down to show off some last apricots, yellow mangoes, pineapples and gooseberries – plus some cherry coke and ginger in the final stages.

That’s quite a lot, yes: and I’m not saying that this is the best and most perfumed rum you’ll ever drink and introduce to all your non-rummy friends as the “one you have to try”; but in its wild cacophony of tastes and smells that pelt everything including the kitchen sink at your senses, it’s almost unbelievable that something so memorable comes out the other end. I particularly liked how Sugar House harnessed, balanced and almost-but-not-quite tamed an intensity and pungency of flavour that in less careful hands would have devolved into an uncoordinated, discombobulated mess.

So is it good, bad, great, or terrible? The answer is yes. To paraphrase a certain film I love to hate, it’s, All-Go-No-Quit-Big-Nuts rum-making, for good or ill (which makes the lack of follow-up batches by Sugar House something of a disappointment). I think the Overproof is an amazing rum, with character and to spare. It sports big tastes, great aromas, and is one of the best and most original whites in recent memory, giving the Jamaicans a serious run for their money. It froths, it bubbles, it hisses, it spits, it takes no prisoners, it’s a joyous celebration of unaged rum, and if you don’t have an opinion on it when you’re done, any opinion at all, maybe you should check your insurance premium when you get home, because it might just have “deceased” stamped on it.

(#978)(90/100) ⭐⭐⭐⭐

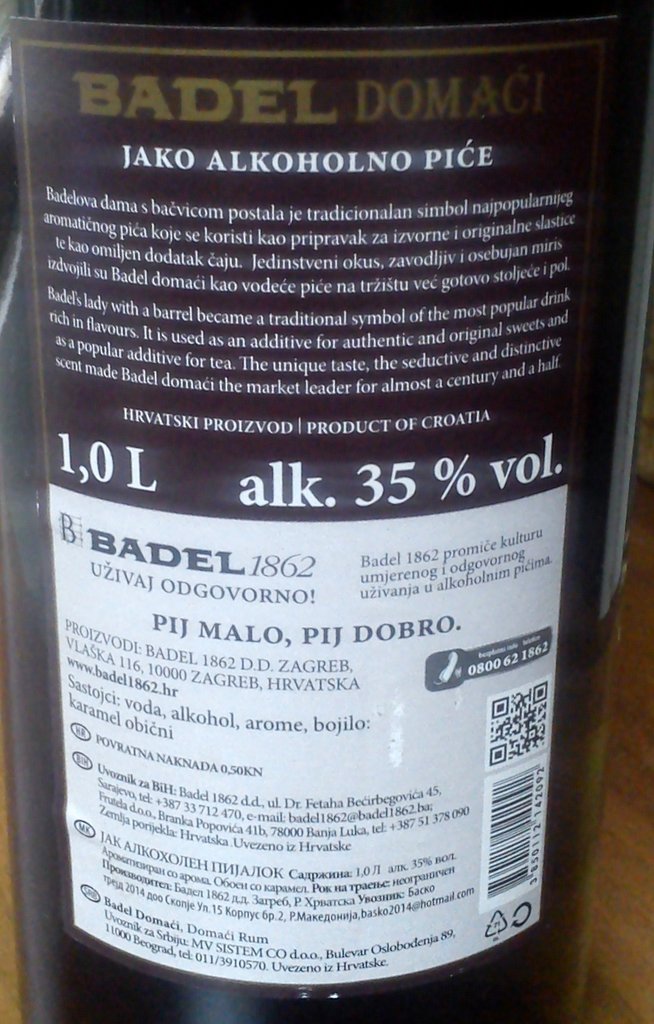

If we accept these data points, then of course the Casino is not, by all current definitions, a rum, and in point of fact, the entry might just as easily be listed in the Rumaniacs page since this version is no longer being made — the word “rum” was either replaced by “room” or dropped completely from the label when Hungary joined the EU in 2004, and that suggests a manufacture for the product I tasted of around 1988-2003 which actually makes it a heritage rum entry, but what the hell.

If we accept these data points, then of course the Casino is not, by all current definitions, a rum, and in point of fact, the entry might just as easily be listed in the Rumaniacs page since this version is no longer being made — the word “rum” was either replaced by “room” or dropped completely from the label when Hungary joined the EU in 2004, and that suggests a manufacture for the product I tasted of around 1988-2003 which actually makes it a heritage rum entry, but what the hell.

Unsurprisingly it’s mostly for sale in the Balkans — Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia, with outliers in Germany — and has made exactly zero impact on the greater rum drinking public in the West. Wes briefly touched on it with a review of

Unsurprisingly it’s mostly for sale in the Balkans — Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia, with outliers in Germany — and has made exactly zero impact on the greater rum drinking public in the West. Wes briefly touched on it with a review of