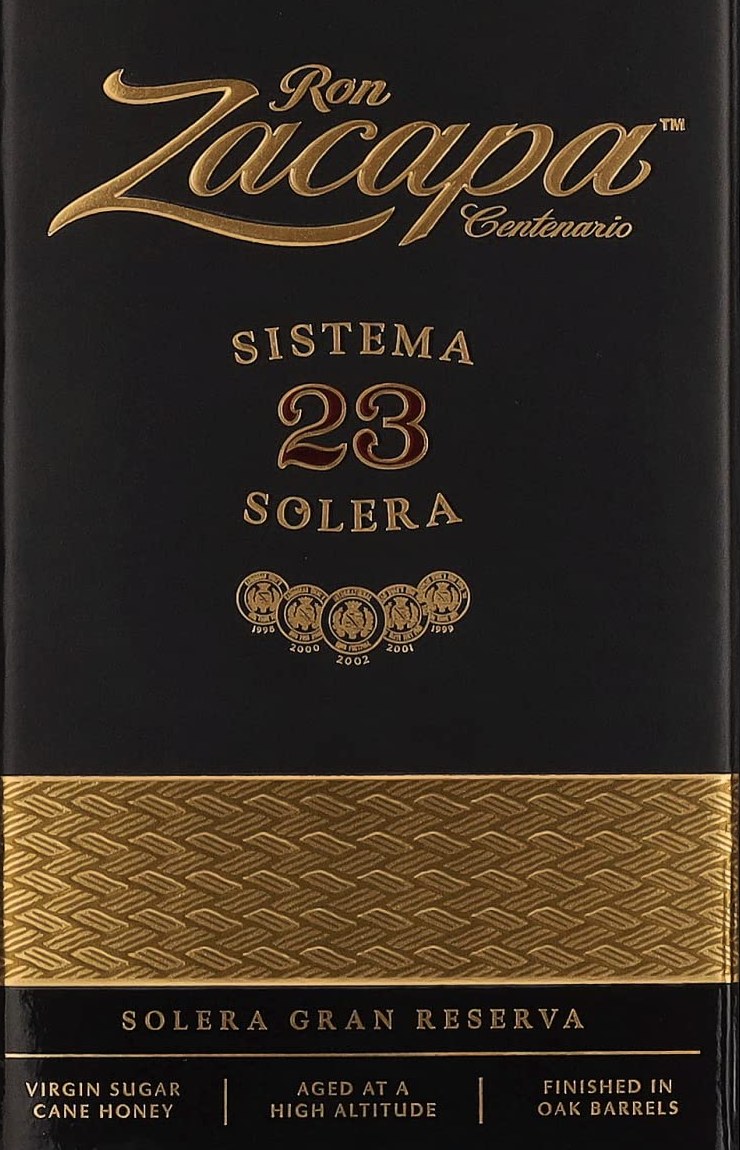

“The Zacapa is here to stay” Wes Burgin said rather glumly, in his recent Rumcast interview, reluctantly acknowledging that if ever there was an indictment of purported rum-based meritocracy where only the good stuff rises to the top, it’s the ubiquity, fame and unkillability of this one Guatemalan rum, long an example trotted out in the seething maelstrom of arguments about what a rum is or should be. There’s a lot wrong with it and a lot right with it and it has equal numbers of foes and friends, but whatever one’s opinion is, everyone has an opinion. Nobody is indifferent, not with this rum. Add to that that it is not entirely a bad drink — come on, let’s face it, there are worse ones out there — and remains one that is globally available, reasonably affordable and always approachable, and you have another controversial Key Rums in the series: the Ron Zacapa Centenario Sistema Solera 23 Gran Reserva.

“The Zacapa is here to stay” Wes Burgin said rather glumly, in his recent Rumcast interview, reluctantly acknowledging that if ever there was an indictment of purported rum-based meritocracy where only the good stuff rises to the top, it’s the ubiquity, fame and unkillability of this one Guatemalan rum, long an example trotted out in the seething maelstrom of arguments about what a rum is or should be. There’s a lot wrong with it and a lot right with it and it has equal numbers of foes and friends, but whatever one’s opinion is, everyone has an opinion. Nobody is indifferent, not with this rum. Add to that that it is not entirely a bad drink — come on, let’s face it, there are worse ones out there — and remains one that is globally available, reasonably affordable and always approachable, and you have another controversial Key Rums in the series: the Ron Zacapa Centenario Sistema Solera 23 Gran Reserva.

It is, like the A.H. Riise, Diplomaticos, Dictadors, Dead Man’s Fingers, Mocambo, Bumbu, Don Papa, Zaya, Kraken, El Dorado and Tanduay and so many others, one of the nexus points of the rumworld, a lightning rod almost inevitably leading to “discussions” and heated outpourings of equal parts love and hate any time someone puts up a post about it (as recently as August 2022, this was still going on, on reddit). And all for the same two reasons – it’s been added to with sugar or caramel or vanillins or more, and the ageing “statement” is deceptive given it’s a solera style rum (therefore the number on the label is at best a shuck-and-jive dance around the truth). It is therefore the hill that anyone who despises adulterated, faux-aged rums is prepared to die on and indeed, in the US there’s a lawsuit filed against Diageo about this very matter.

What the rum does is point out the sheer marketing power of the big conglomerates. No matter how many people hate on this thing or decry its failures, the Zacapa 23 sells like crazy, and there are very few parts of the world I’ve ambled through (and that’s a lot) that don’t sell it. Diageo has used its marketing power to place a rum that is considered substandard (by today’s standards) in everyone’s sightline, and showed that intrinsic quality is near-meaningless…a refutation of Randism if I ever heard it. You don’t think of Guatemala when you hear or see the Zacapa – you just think “23”, and thank God it isn’t “42”.

It wasn’t always this way. A decade ago it was a well-regarded rum with a good reputation that people really enjoyed, won boatloads of prizes, and aside from the ever-vigilant Sir Scrotimus (he kept us safe from nefarious commie rum agents making the world unsafe for democratic drinkers), not many negative comments were ever assigned to it. Moreover, even now you will find the Zacapa 23 in just about all shops, airports and mom-and-pop stores around the world … which is perhaps a sadder commentary on — or necessary correction to — writers’ purported influence.

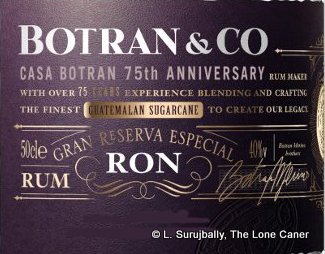

Two events created the backlash against Zacapa (and other sweetened rums) that persists to this day: one was the purchase of a 50% controlling interest of ILG, the parent company of Guatemala’s Zacapa/Botran, by Diageo in 2011, with all the negative connotations and dark suspicions people bring to any multinational buying out a local star boy. The other was the 2014 sugar analyses pioneered and published by Johnny Drejer, which lent full weight to the mistrust people had for Diageo and the changes they had supposedly made to Zacapa (though frankly, this is debatable – some evidence suggests they simply continued existing practises, and actually did us a solid by noting the solera method in the “age statement” on the label). This lack of trust and confidence is what has dogged Zacapa right down to the present, and the whole business about the large number “23” on the label is brought up any time fake age statements are discussed.

Nowadays, the Zacapa 23 is more than just a name for one rum, but the title of the whole brand line: a series of rums stretching from the original Gran Reserva to the new ‘Heavenly Cask’ series like La Doma and El Alma, all bearing the moniker Zacapa 23. Much like Bacardi premiumising the “Facundo” line with several expressions or St Lucia Distillers doing the same with the Chairman’s Reserve series, Zacapa 23 is now lo longer just one but several. It’s the original that still drives sales, though, and although its basic are well known by now, it’s worth repeating them here. The rum is distilled on column stills, from cane juice “honey” (or vesou) fermented with a yeast apparently deriving from pineapples and then aged in ex-bourbon and sherry barrels using what is called a solera, but is in reality probably a complex blend. The result is a blend of rums with ages of 6-23 years, with no proportions ever given.

Nowadays, the Zacapa 23 is more than just a name for one rum, but the title of the whole brand line: a series of rums stretching from the original Gran Reserva to the new ‘Heavenly Cask’ series like La Doma and El Alma, all bearing the moniker Zacapa 23. Much like Bacardi premiumising the “Facundo” line with several expressions or St Lucia Distillers doing the same with the Chairman’s Reserve series, Zacapa 23 is now lo longer just one but several. It’s the original that still drives sales, though, and although its basic are well known by now, it’s worth repeating them here. The rum is distilled on column stills, from cane juice “honey” (or vesou) fermented with a yeast apparently deriving from pineapples and then aged in ex-bourbon and sherry barrels using what is called a solera, but is in reality probably a complex blend. The result is a blend of rums with ages of 6-23 years, with no proportions ever given.

I’ve reviewed the rum twice now, most recently an older version from pre 2010s (2018, 75 points), and once a newer one, but longer ago (2012, unscored, but positive). To write this review I took a currently available version, and it really comes down to filling my glass again to revisit it — and try, with a 2022 sensibility, to come to grips with its peculiar longevity and staying power. Because, why does it still exist and persist? What makes it so popular? Is it always and only the sugar? Or is it just canny marketing aimed at sheeple who blindly take what’s on offer?

Taking a bottle out for a spin makes some of this clear, dispels some notions, confirms others. The nose, for example, is a real pleasant sniff, and even as a seasoned reviewer trying scores of rums at every opportunity, I can’t find much to fault: it starts off with butterscotch, vanilla, coffee, toffee, cocoa, and almonds in a perfectly balanced combination. It’s a sumptuous nose, and let’s not pretend otherwise – that’s what it is. A light sting of alcohol, nothing serious, won’t scare any new premium-rum samplers off. Some light florals and fruits – pears, cherries, apricots an a lighter still touch of pineapples. A sort of light sweetness pervades the entire aromatic profile and if it seems somewhat simple at times, focusing on just a few key elements, well, that’s because it is, and it does. That’s the key to both its durability and appeal.

The nose allows you to see what’s under the hood: or, rather, what you should in theory be tasting, when it comes to that stage. But this is where things turn south because much of what is sensed when smelling it gets tuned down, like an equaliser with too few high-frequency notes and the base ramped too high. The rum feels perfectly pleasant on the tongue: reasonably firm, with some solid salt caramel, vanilla and almond notes, brine, butter, cream cheese. There are sweet caramel bon bons, a bit of fleshy fruits, all held back. More of that toffee and cafe au lait, and enough sweet to be pleasant. If there is some edge it’s in the vague hint of leather and smoke, pleasant, and all too brief, which also describes the finish: this is short, wispy and not assertive enough to make a statement, leaving you mostly with memories of almonds, truffles, toffee and caramel ice cream.

The whole thing is not so much vague as dampened down and the subtler, crisper, more flavourful notes are restrained, as if a soft feather blanket had been placed over them – a characteristic of rums that have additives of any quantity. Since this hides the complexity of what would otherwise be a much dryer and more interesting rum, it presents as something simple and easy and very drinkable (which is both a good and a bad thing – good for newbies who are experimenting in this range, bad for more experienced fans who want more). As such, it’s easy to see why it is such a perennial best seller. Like a Windows computer versus a Mac back in the day, it’s good enough. It’s tasty, no effort really needed, a mite challenging but not enough to cause headaches, and overall, a completely serviceable rum.

So, realistically, the rum is not entirely a fail and within its limits is a tastier-than-expected little hot-weather drink. Even after all these years, it remains a rum most can afford, most can find when they want to buy a “premium”, and it’s easy as hell to get involved with. For a great many consumers it remains the key intro-premium rum, one that gets them past the dreck of Captain Morgan and Bumbu and Krakens they were raised on, and into slightly better rum that will one day lead to…well, even better ones, we can hope, though many simply stop there and go no further. It is a constant reference point for the commentariat and the literature, and many people cut their rum teeth on it. For those not looking to up their game and who like their softer Spanish-style rums and soleras, it’s also the stopping point, a rum they stick with them through thick and thin — many regard with eternal fondness and never quite abandon it for their whole drinking lives.

So, realistically, the rum is not entirely a fail and within its limits is a tastier-than-expected little hot-weather drink. Even after all these years, it remains a rum most can afford, most can find when they want to buy a “premium”, and it’s easy as hell to get involved with. For a great many consumers it remains the key intro-premium rum, one that gets them past the dreck of Captain Morgan and Bumbu and Krakens they were raised on, and into slightly better rum that will one day lead to…well, even better ones, we can hope, though many simply stop there and go no further. It is a constant reference point for the commentariat and the literature, and many people cut their rum teeth on it. For those not looking to up their game and who like their softer Spanish-style rums and soleras, it’s also the stopping point, a rum they stick with them through thick and thin — many regard with eternal fondness and never quite abandon it for their whole drinking lives.

That may not make it a Great Rum. But it trundles along very nicely as one which is key to understanding rums. Because if I were to say what makes the Zacapa something better than it is made to be, it’s that it shows the art of what’s possible for a low end premium. A cheap ten dollar hooch will rarely supersede its origins, and a top-end high-proof thirty-year-old will never get any better (or cheaper) – neither will exceed expectations. The Zacapa sits in the grey area between those two extremes: it excites curiosity, and makes people venture further out into the darker waters of deeper, stronger, wilder, more complex rums. And then, not often, not always, but sometimes, it leads, for some intrigued and interested folk, to all the great rums that lie beyond the borders of the map, where all one knows is that here there be tygers. Seen from that perspective, I contend that the Zacapa 23 should be seriously regarded, not only as a gateway rum, but as a true Key Rum as well.

(#942)(81/100) ⭐⭐⭐½

Other notes

- I am indebted to Dawn Davies of The Whisky Exchange in London who spotted me the bottle from which this review is drawn. I owe her a dinner next time I’m in town.

- Pre-acquisition by Diageo in 2011, the entire Zacapa 23 bottle was enclosed in a straw wrapping. Now only a belt of the material remains; Rum Nation was inspired by — and copied — the wrapping style for their own Millonario 15

- Because of the nature of the article (and its length), it will come as little surprise that I did a lot of reading around on this one. Below is a non-exhaustive list of the major ones.

Reviewers’ links

- Tatu Kaarlas’s 2008 review on Refined Vices, probably the first ever written.

- Rum Ratings of course had to be mentioned. It’s got over 2,000 ratings stretching back a decade, most of which are 7/10 or better, though most of the older ones are the better ones, while newer ones skew lower

- Flaviar has an undated marketing plug that shows what promotional material looks like. It is, of course, epically useless.

- In 2017 The Rum Howler rated it 91.5

- In an earlier review when he was just getting started, The Fat Rum Pirate scored it three stars in 2014.

- Jason’s Scotch Reviews gave a good but unscored review in 2020

- Reinhard Pohorec on the Bespokeunit lifestyle website which bills itself as a “Guide to a dapper life” gave a fulsome review of the rum in 2021.

- The UK rum blog Rumtastic, in an unscored 2016 essay, commented that it was “really too sweet” and noted its unchallenging nature

- Serge rather savagely dissed and dismissed it with a contemptuous 50 points in 2016 after having given 75 points to pretty much the same one in 2014

- MasterQuill 2015 a rather meh 80 points

- Henrik at Rum Corner liked it at the beginning of his journey, not so much by the end. His 2016 review remains the best ever written on that rum, and his observations are on point even today

- Dave Russell rated it 8.5 points in a 2017 review and in a head to head with the “Anos” version stated there was no discernible difference pre- and post- Diageo. That might sound fine until you realise that whatever the modern variation has, the older version must therefore have had too.

- Cyril of DuRhum gave it an indifferent unscored review himself, but it’s his 2015 sugar analysis that made it clear what was going on.

- Rum Robin on the solera method but not a review.

- Tony Sachs wrote the most recent review of the rum in 2022, and one of the better roundups of the issues surrounding it.

Magazine articles

The name of the rum (or ron, if you will) relates back to the Mayan motif that has been part of the brand from the inception:

The name of the rum (or ron, if you will) relates back to the Mayan motif that has been part of the brand from the inception:

That’s not to say that in this case the

That’s not to say that in this case the