Introduction

Brutta ma buoni is an Italian phrase meaning “ugly but good”, and as I wrote in the SMWS 3.5 “Marmite” review, describes the oversized codpieces of the “151” types of rums very nicely indeed. These glute-flexing ABV beefcakes have been identifiably knocking people into stupors for at least since the 1930s and possibly even before that — and while they were never entirely good, when it came to serving up a real fast drunk with a hot-snot shot of whup-ass, they really couldn’t be beat. Flavours were often secondary, proof-power everything.

Everyone involved with rums — whether bartender, barfly or boozehound — knows what a “151” is, and they lend themselves to adverbial flights of fancy, humorous metaphors and some funny reviews. They were and are often conflated with “overproof” rums – indeed, for a long time they were the only overproofs known to homo rummicus, the common rum drinker – and their claim to fame is not just a matter of their alcohol content of 75.5% ABV, but their inclusion in classic cocktails which have survived the test of time from when they were first invented.

But ask anyone to go tell you more about the 151s, and there’s a curious dearth of hard information about them, which such anecdotes and urban witticisms as I have mentioned only obscure. Why, for example, that strength? Which one was the first? Why were there so many? Why now so few? A few enterprising denizens of the subculture would mention various cocktail recipes and their origin in the 1930s and the rise of tiki in the post war years. But beyond that, there isn’t really very much, and what there is, is covered over with a fog suppositions and educated guesses.

Mythic Origins – 1800s to 1933

Most background material regarding high-proof rums such as the 151s positions their emergence in the USA during the Great Depression – cocktail recipes from that period called for certain 151 proof rums, and America became the spiritual home of the rum-type. What is often overlooked is that if a recipe at that time called for such a specific rum, by name, then it had to already exist — and so we have to look further back in time to trace its origins.

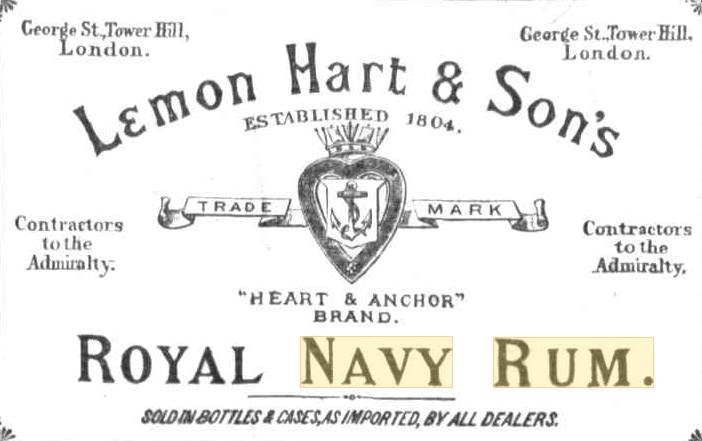

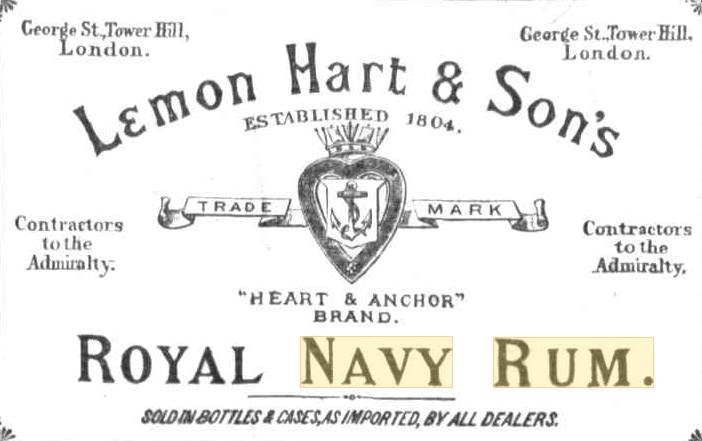

1873 Australian newspaper ad for Lemon Hart (Rum History FB page)

That line of thinking brings us to Lemon Hart, probably the key company behind the early and near-undocumented history of the 151s. It had to have been involved since, in spite of their flirting with bankruptcy (in 1875) and changes in ownership over the years, they were as far as I am aware, among the only ones producing anything like a widely-sold commercial overproof in the late 1800s and very early 1900s (quite separate from bulk suppliers like Scheer and ED&F Man who dealt less with branded bottles of their own, but supplied others in their turn). Given LH’s involvement with the rum industry, they had a hand in sourcing rums from the West Indies or from ED&F Man directly, and this made them a good fit for supplying other British companies. Their stronger rums and others’, so far as I can tell, tended to just be called overproofs (meaning greater than 57% for reasons tangential to this essay but related to how the word proof originated to begin with¹)…but not “151”.

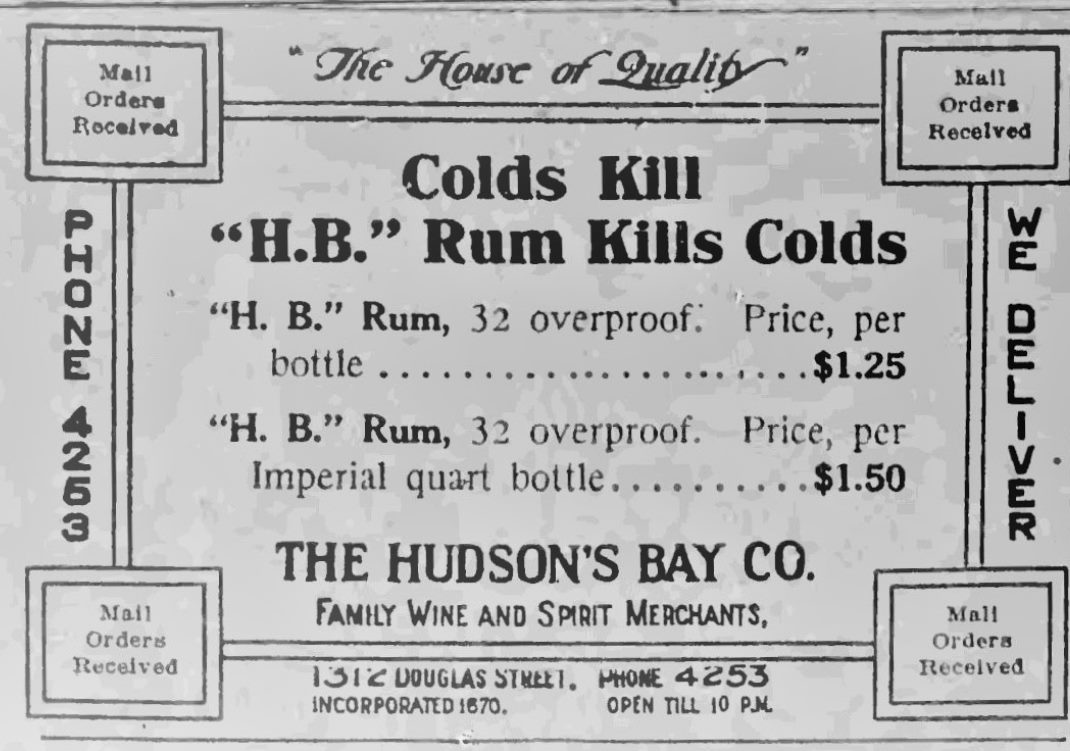

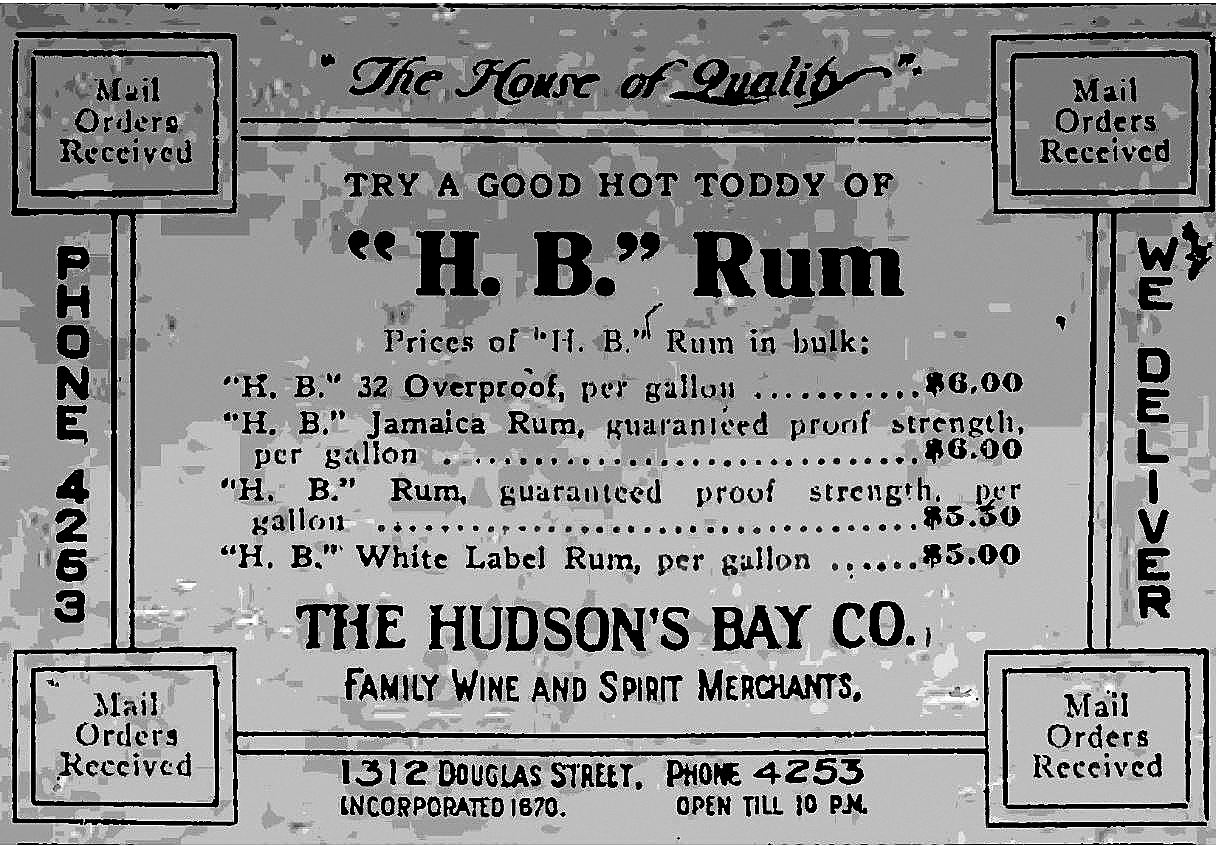

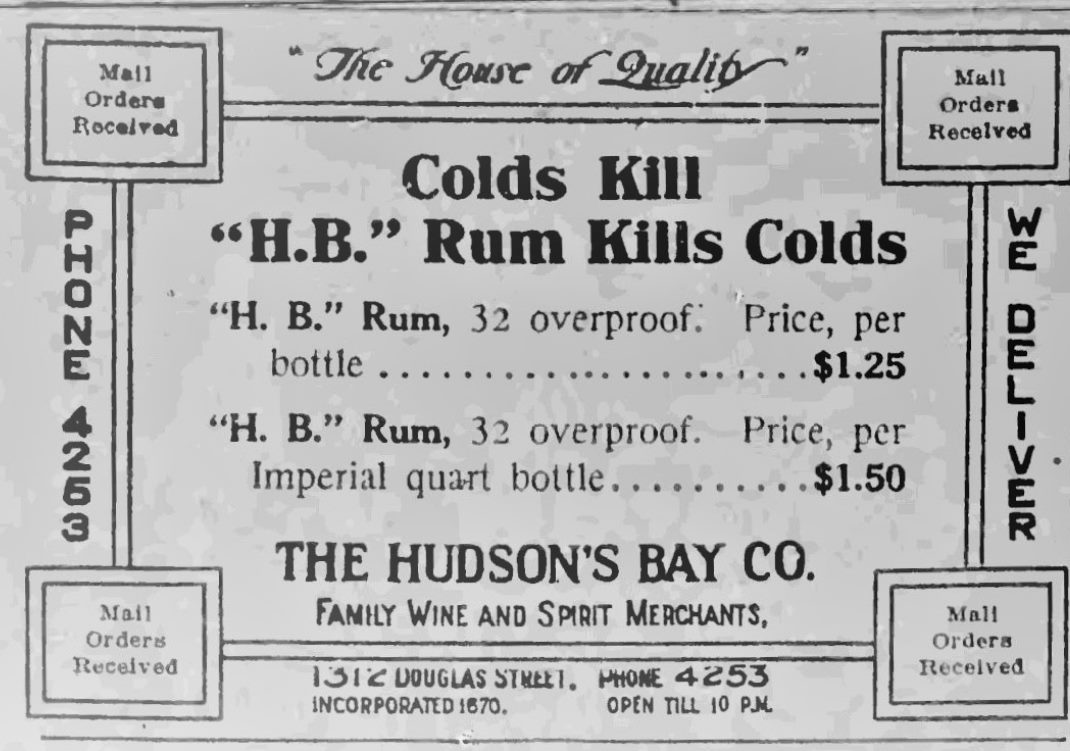

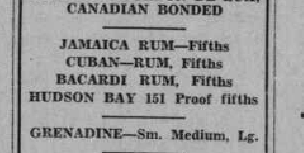

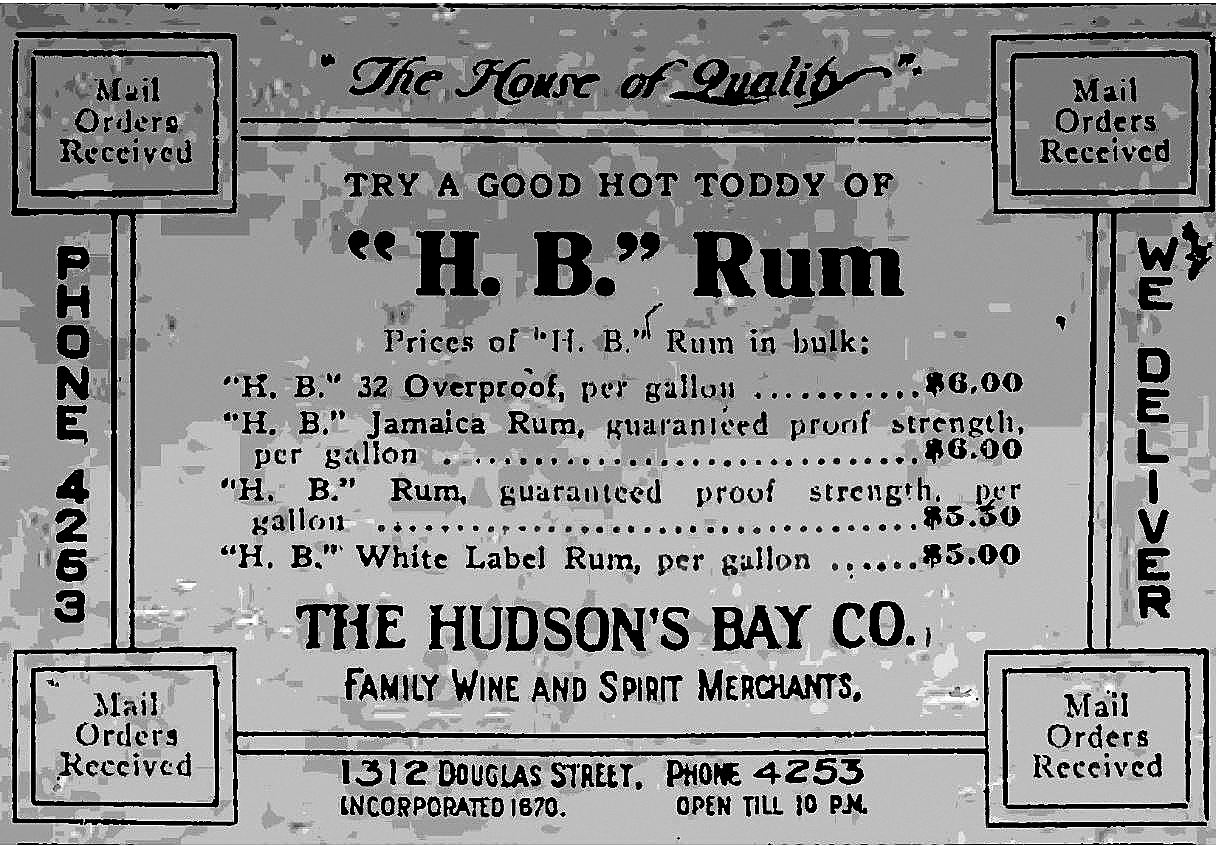

Victoria Daily British Colonist, March 11, 1914. Ad for a 32 Overproof rum, which is what 151s were once called

Navy rums were considered the beefcake proofed rums of their day, and certainly stronger ones did exist – the 69% Harewood House Barbados rum bottled in 1780 is an example – but those that did were very rarely commercially bottled, and probably just for estate or plantation consumption, which is why records are so scant. The real question about rums bottled north of 57% was why bother to make them at all? And what’s that story that keeps cropping up, about a British / Canadian mercantile concern having something to do with it?

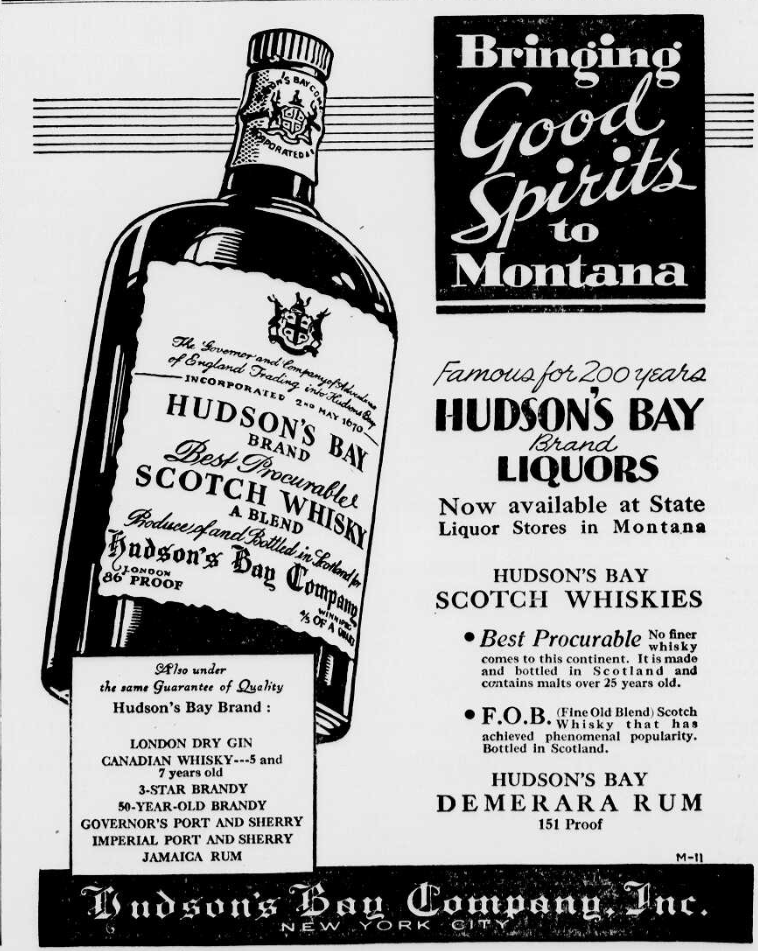

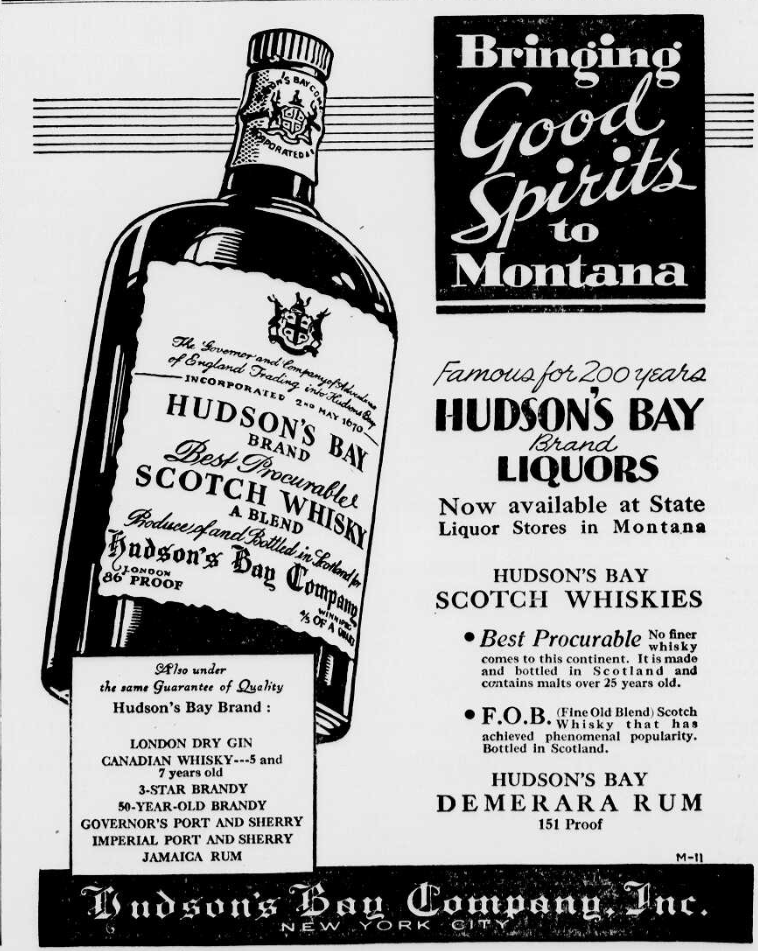

Earliest record of a 151 rum. the Canadian HBC – 1934, Montana, USA

Here’s the tale: the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) was incorporated by Royal Charter in 1670, and was not only the first great trading concern in North America – it had its origins in the fur trade and trading posts of the British-run northern part of the continent – but for some time was almost a quasi-Government of large parts of the vast territories that became Canada. Their chain of trading posts morphed into sales shops which also sold alcohol – but as Steve Remsberg remarked in relating this possibility, the story (without proof, ha ha) goes that rums with proof strengths or lower were insufficient for the business of the HBC in the 1800s: it froze in the deep cold above the Arctic Circle, and so something with more oomph was required (mind you, at that time they sold mostly brandy and gin, not rum so much, but I have no doubt that rum was also part of their overall alcoholic portfolio given their Canada’s long history with rum, and HBC’s identification with it later). This tale was supported in Charles H. Baker’s 1951 book “The South American Gentleman’s Companion” (p. 77 and 78) where he remarked “Ordinary proof rums, shipped up to the chill winter wastes round Hudson Bay in Canada, promptly froze and burst their bottles. 151 proof was finally hit upon as proper proof to weather that cruel wintering.” However, the source reference of the story itself is not cited or dated, and as Matt Pietrek noted, both Curtis and Remsburg might have used it as their source.

Lemon Hart had a strong presence in the colonies (it was big in Canada and huge in Australia through the late 1800s to early 1900s, for example), possessing connections to the main importer of rum and the Caribbean rum industry, and can reasonably be construed to have been involved in bootstrapping these efforts into an even stronger version of their regular rums to address HBC’s requirements, a theory I put forward because there really wasn’t any other company which was so firmly identified and tied to the rum-type in years to come, or so suitably positioned to do so for another major British mercantile concern². There is, unfortunately, no direct evidence here, I just advance it as a reasoned conjecture that fits tolerably well with such slim facts as are known. It is equally possible that HBC approached major rum suppliers like Man independently….but somehow I doubt it.

1935 Fairbanks Daily News (Alaska, USA) ad

Whatever the truth of the matter, by the early 1900s some kind of overproof “style” — no matter who made it — is very likely to have become established across North America, and known about, even if a consistent standard strength over 57% had not been settled on, and the term “151” might not have yet existed. Certainly by 1914 the strength had been used – it just wasn’t called “151,” but “32 Overproof”. (If we assume that proof was defined as 100º (57.14% ABV) then 32 Overproof worked out to 132º proof and the maths makes this 75.43%…close enough for Government work for sure). Unsurprisingly, this was also the Hudson’s Bay Company, which marketed such a 32 Overproof in British Columbia as far back as 1914 (see above).

The Daily Colonist, Victoria, Vancouver Island B.C, 01 May 1914

However, I suggest that such high-powered rums would have remained something of a niche spirit given their lack of branding and advertising, and they might have stayed in the shadows, were it not for the enactment of the Volstead Act in the USA and similar legislation in Canada after the restrictions of the First World War.

That drove the category underground…while simultaneously and paradoxically making it more popular. Certainly the strength of such a rum made it useful to have around…from a logistical standpoint at least. Because quite aside from its ability to get people drunker, faster (and even with its propensity to remain liquid at very low temperatures of the North), from a shipping perspective its attraction was simply that one could ship twice as much for the same cost and then dilute it elsewhere, and make a tidy profit.

Although direct evidence is lacking, I am suggesting that sometime between 1920 and 1933 (the dates of American Prohibition) a consistent strength was settled on and the title “151” was attached to rums bottled at 75.5%, and it was an established fact of drinking life, though maddeningly elusive to date with precision. Cocktail recipes now called for them by name, the public was aware, and the title has never disappeared.

The Strength

So why 151? Why that odd strength of 75.5%, and not a straight 70%, 75% or 80%? We can certainly build a reasonable chain of supposition regarding why overproofed spirits were made at all, why Lemon Hart and HBC made something seriously torqued-up and therefore why subsequent cocktails called for it…but nailing down that particular number is no longer, I believe, possible. It’s just been too long and the suppositions too varied, and records too lacking.

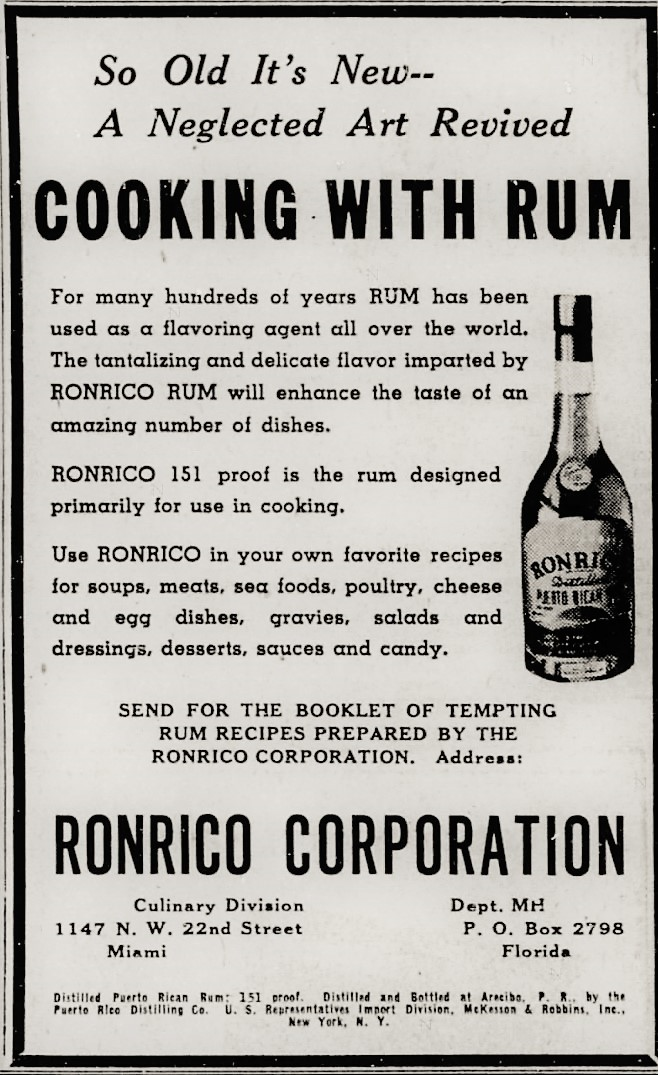

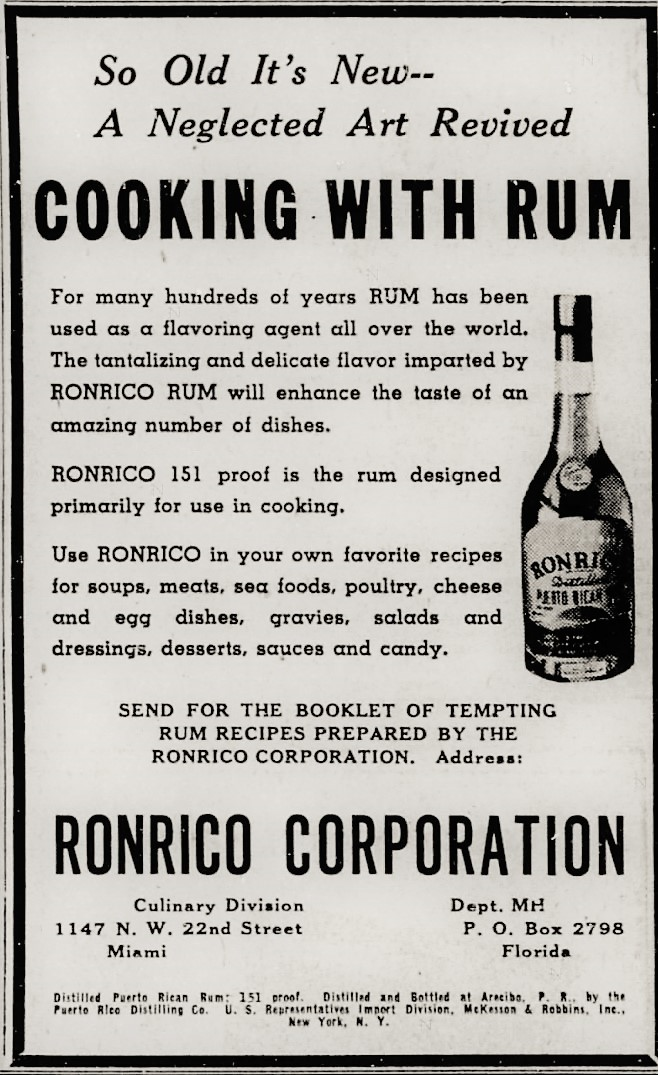

1938 Ron Rico advertisement

One theory goes that some US state laws (California and Florida specifically) required that proofage (or a degree higher) as the maximum strength at which a commercial consumable drink could be made — this strikes me as untenable given its obvious limitations, and in any case, it’s a factoid, not an explanation of why it was selected. Ed Hamilton of the Ministry of Rum suggested that the strength was roughly the output strength of a historic pot still – distillate would have come off after a second pass or a retort at about 75% abv — but since Puerto Rico was making rums at that strength without any pot stills quite early on (Ron Rico advertised them for being useful for cooking, which is an intriguing rabbit hole to investigate) this also is problematic. Alternatively, it might have been the least dangerous yet still cost-effective way of shipping bulk rum around prior to local dilution, as noted above. Or because of the flash point of a 75% ethanol / 25% water mix is about the ratio where you can set it on fire without an additional propellant or heating the liquid (also technically unlikely since there are a range of temperatures or concentrations where this can happen). And of course there’s Steve Remsburg’s unproven but really cool idea, which is that it was a strength gradually settled on as rums were developed for HBC that would not freeze in the Arctic regions.

All these notions have adherents and detractors, and none of them can really be proven (though I’d love to be shown up as wrong in this instance). The key point is that by 1934, the 151s existed, were named, released at 75.5%, and already considered a norm – and interestingly, they had become a class of drinks that were for the most part an American phenomenon, not one that grew serious legs in either Asia or Europe. How they surged in popularity and became a common part of every bar’s repertoire in the post-war years is what we’ll discuss next.

Tiki, the Beachcomber, Lemon Hart et al – 1934-1963

Tiki, the Beachcomber, Lemon Hart et al – 1934-1963

In spite of the 151s’ modern bad-boy reputations — as macho-street-cred testing grounds, beach party staples, a poor man’s hooch, where one got two shots for the price of one and a massive ethanol delivery system thrown in for free — that was a relatively recent Boomer and Gen X development. In point of fact, 151s were, for most of the last ninety years, utilized as cocktail ingredients, dating back to the dawn of the tiki era started in the 1930s and which exploded in the subsequent decades. And more than any other rum of its kind, the rep of being the first 151 belonged to the famed Lemon Hart 151, which was specifically referenced in the literature of the time and is the earliest identifiable 151 ancestor.

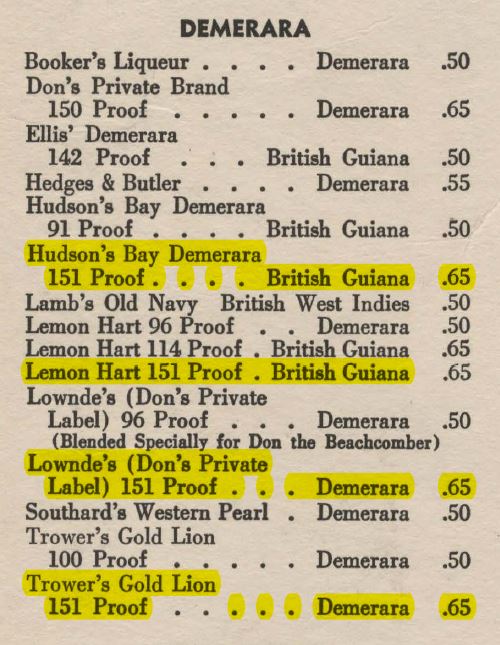

So if there was ever a clear starting point to the 151s’ rise to prominence, then it had to have been with the repeal of American Prohibition in 1933 (Canada’s Prohibition was more piecemeal in execution and timing of implementation varied widely among provinces, but in almost all cases lasted less than a decade, during the ‘teens and 1920s). Within a year of the US repeal, both Canada’s Hudson’s Bay Company liquor division and the UK rum supplier Lemon Hart had made 151-proof rums, explicitly naming them as such (and not as some generic “overproof”), and positioning them for sale in the advertisements of the time.

This came about because of the opening of Don’s Beachcomber, a Polynesian themed restaurant and bar in Hollywood, run by an enterprising young man named Ernest Raymond Beaumont-Gant, who subsequently changed his name to Donn Beach to jive with the renamed “Don the Beachcomber” establishment. His blend of Chinese cuisine, tropical-themed rum cocktails and punches and interior decor to channel Polynesian cultural motifs proved to be enormously influential and spawned a host of imitators, the most famous of whom was Victor Bergeron, who created a similar line of Tiki bars named Trader Vic’s in the post war years, to cater to renewed interest in Pacific islands’ culture.

The key takeaway from this rising interest in matters tropical and tiki, was the creation of ever more sophisticated cocktails using eight, nine, even ten ingredients or more. Previous 19th and early 20th century recipes stressed three or four ingredients, used lots of add-ins like vermouth and bitters and liqueurs, and at best referred to the required rums as “Jamaica” or “Barbados” or what have you. Then as now, there were no shortage of mixes – the 1932 Green Cocktail book lists 251 of them and a New York bartender’s guide from 1888 has nearly two hundred.

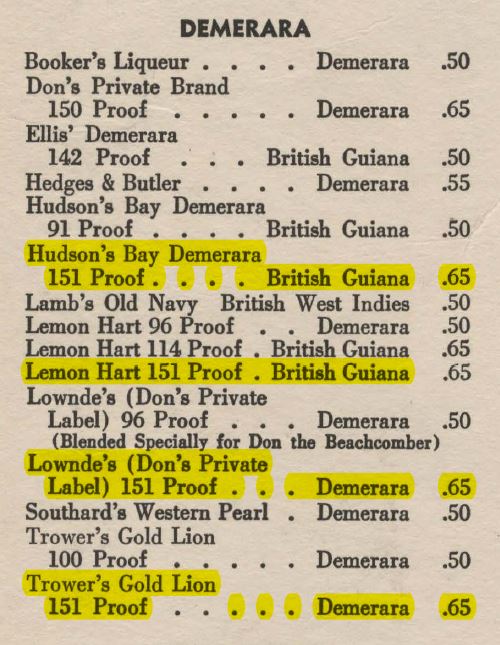

Extract from Don the Beachcomber 1941 drinks menu

What distinguished Beach and Bergeron and others who followed, was their innovative and consistent use of rums, which were identified in some cases by name (like the Lemon Hart 151 or the Wray & Nephew 17 year old), with several now-classic cocktails being invented during this period: the Zombie, the Mai Tai, the Three Dots and a Dash, the Blue Hawaii and the 151 Swizzle, among others. Not all these required high proof rums, but two – the Zombie and the Swizzle – absolutely did, and by 1941, the Beachcomber’s rum list had several 151 variants including branded ones like Lemon Hart, Lownde’s, and Trower’s….and yes, HBC.

Initially the Lemon Hart 151 was the big gun in the house and was explicitly referenced in the recipes of the time, like for the Zombie, which Beachbum Berry spent so much time tracking down. But if one were to peruse the periodicals of the day one would note that they were not the only ones advertising their strong rums: in the mid to late 1930s: the Canadian Hudson’s Bay Company liquor arm, and a Puerto Rican brand called Ron Rico (made just as the Serralles’ firm launched the Don Q brand with a newly acquired columnar still – they acquired Ron Rico in 1985) were also there, showing the fad was not just for one producer’s rum, and that a market existed for several variations.

The forties’ war years were quiet for 151s, but by the 1950s — with post-war boom times in the USA, and the rise of the middle class (and their spending power) — their popularity began to increase, paralleling the increase in awareness of rums as a whole. Tens of thousands of soldiers returned from duty in the Pacific, movies extolled the tropical lifestyle of Hawaii, and members of the jet set, singers and Hollywood stars all did their bit to fuel the Polynesian cultural explosion. And right alongside that, the drinks and cocktails were taking off, spearheaded by the light and easy Spanish style blends such as exemplified by Bacardi. This took time to get going, but by the early 1960s there was no shortage of 151 rums — from Puerto Rico in particular, but also from Jamaica and British Guiana — to rank alongside the old mainstays like Lemon Hart.

The Era of Bacardi – 1963-2000

The Era of Bacardi – 1963-2000

It may be overstating things to call these years an era of any kind: here, I simply use it as a general shorthand for a period in which 151s were no longer exotic but an established rum category in their own right, with all their attendant ills.

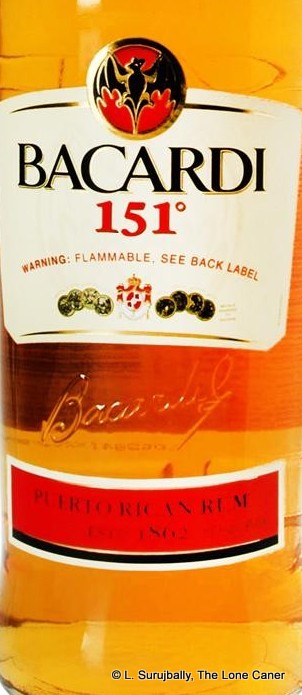

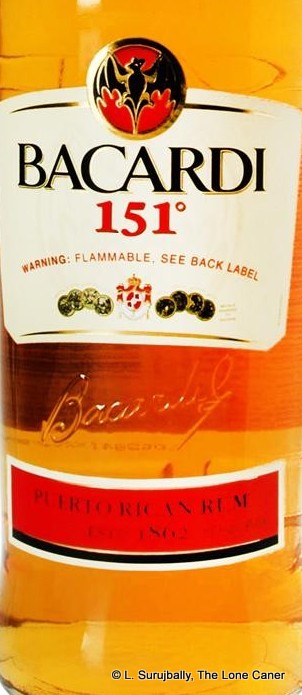

As with most ideas that make money, sooner or later big guns and small come calling to join the party. Bacardi had its problems by being ousted from Cuba in 1960, yet had had the foresight to diversify their company even before that, and operated in Brazil, Mexico, Puerto Rico and the USA. After the dust settled, they made their own 151 in the lighter Cuban style – at the time it was made in Brazil before production shifted to Puerto Rico, and its low and subsidized price made it a perennially popular rum popskull. It was widely available and affordable, and therefore soon became the bestselling rum of its type, overtaking and outselling all other 151 brands such as the Appleton 151 white, or the Don Q 151 made by the Serralles boys in Puerto Rico and those that had existed even earlier.

The official basis of the popularity of 151s remained the cocktails one could make with them. Without searching too hard, I found dozens of recipes, some calling for the use of Bacardi 151 alone, with names as evocative as “the Flatliner”, “Four Horsemen”, “Backfire on the Freeway”, “Superman’s Kryptonite” and “Orange F*cker”. Obviously there were many more, and if Bacardi seemed ubiquitous after a while, it was because it was low-cost and not entirely piss-poor (though many who tried it neat over the years might disagree).

One other demographic event which propelled 151s to some extent was the rise of the western post-war Baby Boomer generation and its successors like Gen-Xers who had known little privation or want or war in their lifetimes. These young people raised on Brando-esque machismo and moody Dean-style rebellion, had disposable income and faced the enormous impact of American popular culture — for them, 151s served another purpose altogether, that of getting hammered fast, and seeing if one could survive it…some sort of proof-of-manhood kind of thing. Stupidity, hormones, youth, party lifestyle, the filmic romance of California beaches, ignorance, take your pick. For years – decades, even – this was the brush that tarred 151s and changed their popular perceptions.

In all that happy-go-lucky frat-boy party reputation combined with the allure of easily-made, inexpensive home-made concoctions, lay the seeds of its destruction (to Bacardi, at any rate). People got hurt while under the highly intoxicating influence of killer mixes, got into accidents, did stupid and dangerous things. 151s were highly flammable, and property damage was not unheard of, either by careless handling or by inexpert utilization of the overproofs in flambees or floats. Unsurprisingly in a litigious culture like the USA, lawsuits were common. Bacardi tried to counter this by printing clear warnings and advisories on its labels, to no avail, and finally they decided to pull the plug in 2016 in order to focus on more premium rum brands that did less harm to their reputation.

In all that happy-go-lucky frat-boy party reputation combined with the allure of easily-made, inexpensive home-made concoctions, lay the seeds of its destruction (to Bacardi, at any rate). People got hurt while under the highly intoxicating influence of killer mixes, got into accidents, did stupid and dangerous things. 151s were highly flammable, and property damage was not unheard of, either by careless handling or by inexpert utilization of the overproofs in flambees or floats. Unsurprisingly in a litigious culture like the USA, lawsuits were common. Bacardi tried to counter this by printing clear warnings and advisories on its labels, to no avail, and finally they decided to pull the plug in 2016 in order to focus on more premium rum brands that did less harm to their reputation.

That singularly unspectacular happening (or non-happening) was accompanied in the subsequent months and years by retrospectives and newsbytes, and a peculiar outpouring of feelings by now-grown-up man-children who, from their home bars and man-caves, whimsically and poetically opined on its effect on their lives, and – more commonly – the tearful reminiscences of where they first got wasted on it, and the hijinks they got up to while plastered. It did not present the nobility of the human race in its best light, perhaps, but it did show the cultural impact that the 151s, especially Bacardi’s, had had.

151s in the New Century – a decline, but not a fall

The discontinuation of Bacardi’s big bad boy obscured a larger issue, which was that these rums had probably hit their high point in the 1980s or 1990s, when it seemed like there was a veritable treasure trove of now-vanished 151 brands to choose from: Carioca, Castillo, Palo Viejo, Ron Diaz, Don Lorenzo, Tortuga and Trader Vic’s (to name a few). It was entirely possible that this plethora of 151s was merely a matter of “me too” and “let’s round out the portfolio”. After all, at this time blends were still everything, light rum cocktails that competed with vodka were still the rage, neat drinking was not a thing and the sort of exacting, distillery-led, estate-specific rum making as now exists was practically unheard of (we had to wait until the Age of Velier’s Demeraras to understand how different the world was before and after that point).

But by the close of the 1990s and the dawn of the 2000s, blends — whether high proof or not — already showed a decline in popular consciousness. And in the 2010s as independents began to release more and better high-proofed single-barrel rums, they were followed by DDL, Foursquare, St. Lucia Distillers, Hampden, Worthy Park and other makers from countries of origin, who started to reclaim their place as rum makers of the first instance. Smaller niche brands of these 151s simply disappeared from the rumscape.

But by the close of the 1990s and the dawn of the 2000s, blends — whether high proof or not — already showed a decline in popular consciousness. And in the 2010s as independents began to release more and better high-proofed single-barrel rums, they were followed by DDL, Foursquare, St. Lucia Distillers, Hampden, Worthy Park and other makers from countries of origin, who started to reclaim their place as rum makers of the first instance. Smaller niche brands of these 151s simply disappeared from the rumscape.

The fact was, in the new century, 151s were and remained tricky to market and to promote. They exceeded the flight safety regulations for carrying on some airlines (many of whom cap this at 70% ABV, though there are variations) and the flammability and strength made many retailers unwilling to sell them to the general public. There was an ageing crop of people who grew up on these ferocious drinks and would buy them, sure, but the new generation of more rum-savvy drinkers was less enamoured of the style.

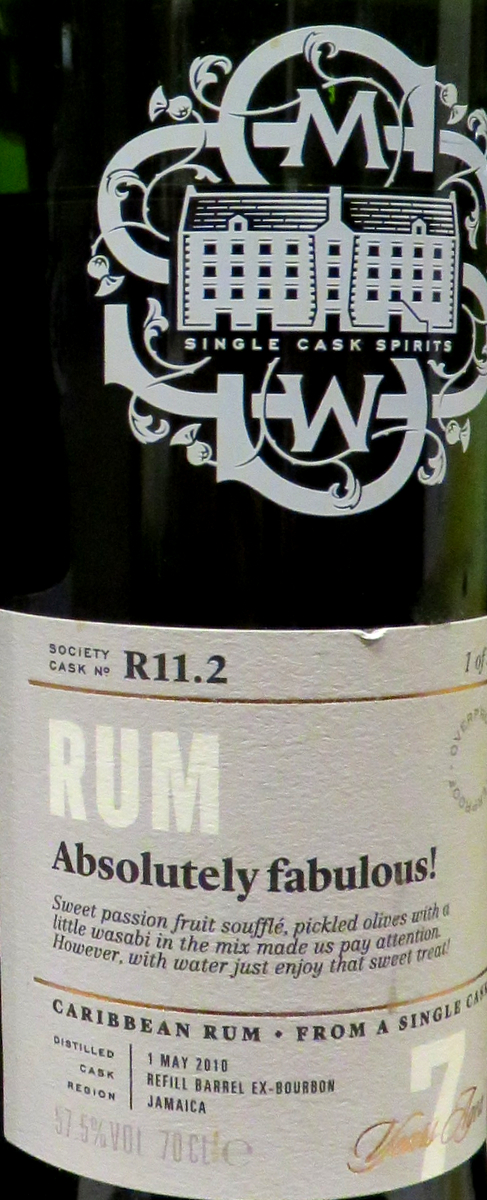

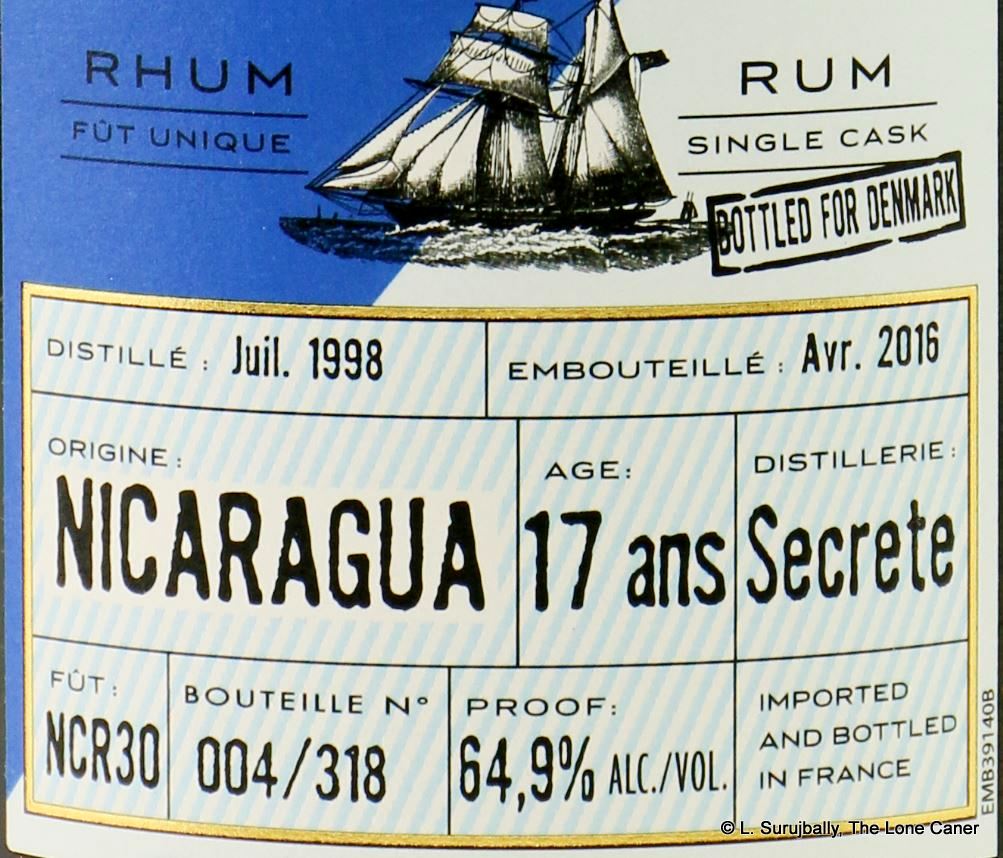

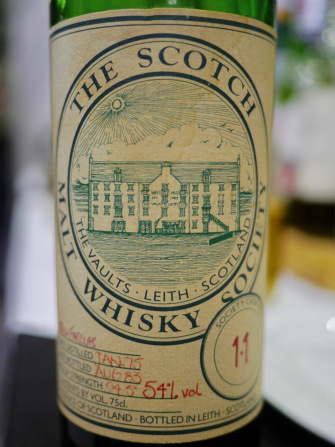

Which was not surprising, given the ever-increasing panoply of selections they had. The growing indifference of the larger drinking public to 151s as a whole was aided by the explosion of rums which were also overproofs, but not quite as strong, and – more importantly – which tasted absolutely great. These were initially IB single barrel offerings like those of the SMWS or L’Esprit or Velier, and also juice from the Seychelles (Takamaka Bay), Haiti (the clairins), Martinique (Neisson L’Esprit 70º), and the highly popular and well-received Smith & Cross, Rum Fire, Wray & Nephew 63% White, Plantation OFTD, and on and on. These served the same purpose of providing a delicious alcoholic jolt to a mix (or an easy drunk to the rest), and were also affordable – and often received reviews in the internet-enabled blogosphere that the original makers of the 151s could only have dreamed about.

Photo montage courtesy of and (c) Eric Witz from FB, Instagram @aphonik

Many such producers of 151s have proved unable or unwilling to meet this challenge, and so, gradually, they started to fade from producers’ concerns, supermarket shelves, consumers’ minds…and became less common. Even before the turn of the century, mention of the original 151s like Hudson’s Bay, Lownde’s and Trowers had vanished; Bacardi, as stated, discontinued theirs in 2016, Appleton possibly as late as 2018 (their Three Dagger 10YO 151 pictured above was gone by the 1960s), and many others whose names are long forgotten, fell by the roadside way before then. Nowadays, you hardly see them advertised much, any more. Producers who make them – and that isn’t many – are almost shamefacedly relegating them to obscure parts of their websites, same as retailers tucking them away in the back-end bottom shelf. Few trumpet them front and centre any longer. And on the consumer side, with drinkers and bartenders being spoiled for choice, you just don’t see anyone jumping up on social media crowing how they scored one…except perhaps to say they drank one .

But the story doesn’t end here, because some producers have indeed moved with the times and gone the taste-specific route, gambling on bartenders and cocktail books’ recommending their 151s from an ever-shrinking selection.

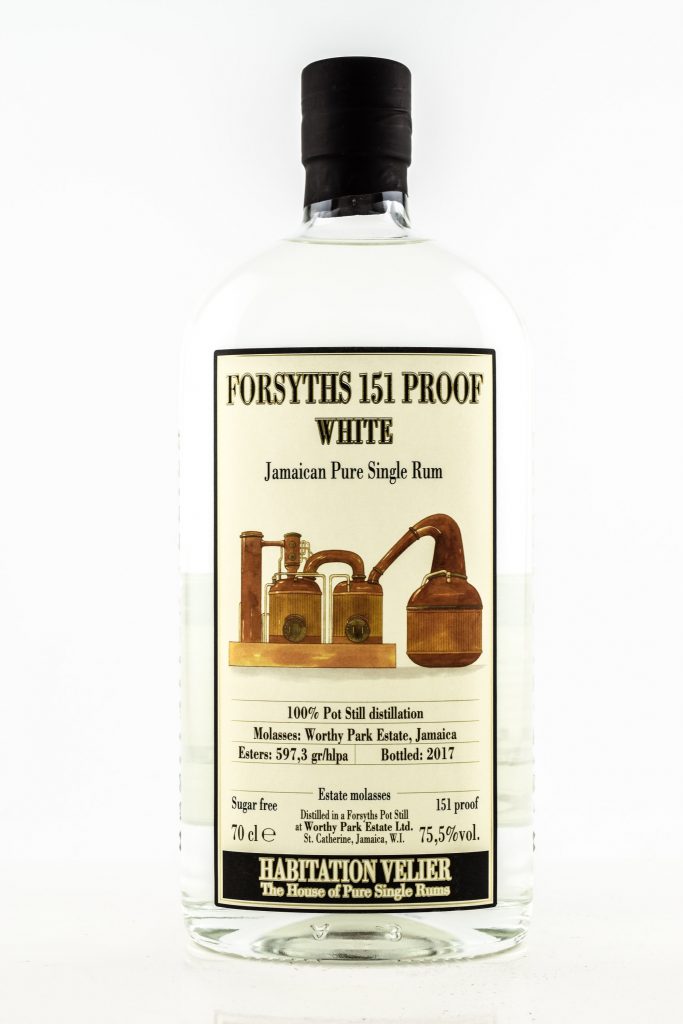

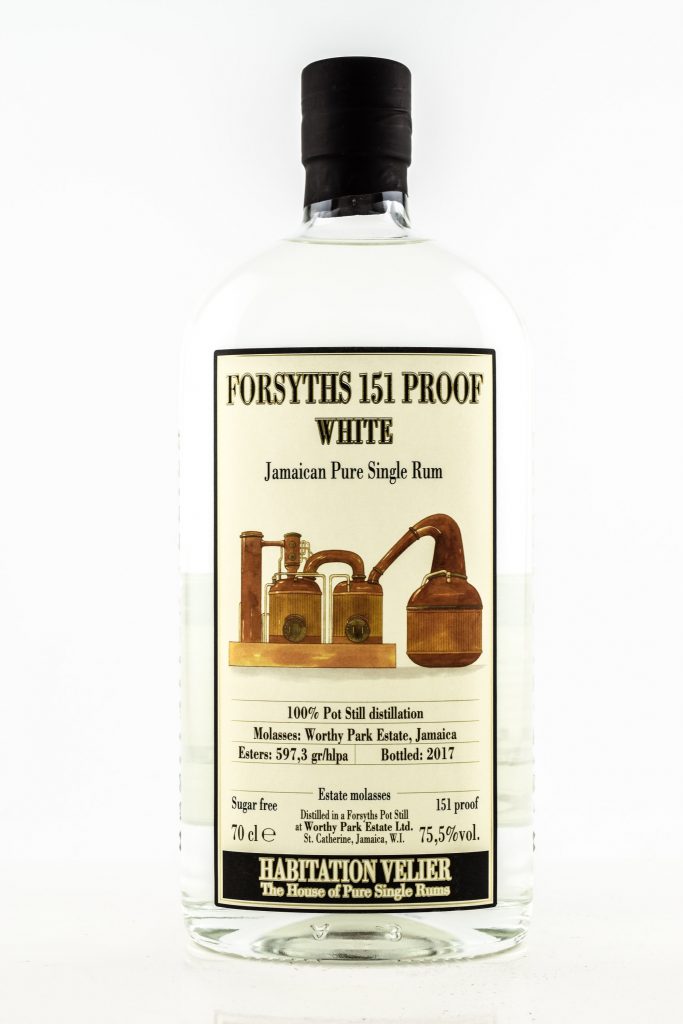

Lemon Hart was, of course, the poster child for this kind of taste-specific Hulkamaniac of taste – they consistently used Demerara rum, probably Port Mourant distillate, for their 151, and even had a Jamaican 73% rum that boasted some serious flavour chops. Internal problems caused them to falter and cease selling their 151 around 2014, and Ed Hamilton (founder of both the website and the Facebook page “the Ministry of Rum”) jumped into the breach with his own Hamilton 151, the first new one of its kind in years, which he released in 2015 to great popular acclaim. The reception was unsurprising, because this thing tasted great, was an all-Guyana product and was aimed at a more discriminating audience that was already more in tune to rums bottled between 50%-75%. And that was quite aside from the bartenders, who still needed 151s for their mixes (as an aside, a rebranded Lemon Hart 151 was released in 2012 or thereabouts with a wine red label and was again subsequently discontinued a few years later). Even Velier acknowledged the uses of a 151 when they released a Worthy Park 151 on their own as part of the Habitation Velier line of pot still rums (and it’s great, btw). And in an interesting if ultimately stalled move that hints a the peculiar longevity of 151s, Lost Spirits used their Reactor to produce their own take on a Cuban Inspired 151– so irrespective of other developments, the confluence of strength, flexibility of use and enormity of taste has allowed some 151s to get a real lease on life.

Lemon Hart was, of course, the poster child for this kind of taste-specific Hulkamaniac of taste – they consistently used Demerara rum, probably Port Mourant distillate, for their 151, and even had a Jamaican 73% rum that boasted some serious flavour chops. Internal problems caused them to falter and cease selling their 151 around 2014, and Ed Hamilton (founder of both the website and the Facebook page “the Ministry of Rum”) jumped into the breach with his own Hamilton 151, the first new one of its kind in years, which he released in 2015 to great popular acclaim. The reception was unsurprising, because this thing tasted great, was an all-Guyana product and was aimed at a more discriminating audience that was already more in tune to rums bottled between 50%-75%. And that was quite aside from the bartenders, who still needed 151s for their mixes (as an aside, a rebranded Lemon Hart 151 was released in 2012 or thereabouts with a wine red label and was again subsequently discontinued a few years later). Even Velier acknowledged the uses of a 151 when they released a Worthy Park 151 on their own as part of the Habitation Velier line of pot still rums (and it’s great, btw). And in an interesting if ultimately stalled move that hints a the peculiar longevity of 151s, Lost Spirits used their Reactor to produce their own take on a Cuban Inspired 151– so irrespective of other developments, the confluence of strength, flexibility of use and enormity of taste has allowed some 151s to get a real lease on life.

Others are less interesting, or less specific and may just exist, as many had before, to round out the portfolio – Don Q from Puerto Rico makes a 151 to this day, and Tilambic from Mauritius does as well; El Dorado is re-introducing a new one soon (the Diamond 151, I believe), and Cruzan (Virgin Islands), Cavalier (Antigua), Bermudez (Dominican Republic), and Ron Carlos (USA) have their 151s of varying quality. Even Mhoba from South Africa joined the party in late 2020 with its own high ester version. The point is, even at such indifferent levels of quality, they’re not going anywhere, and if their heyday has passed us by, we should not think they have disappeared completely and can only be found, now, in out of the way shops, auctions or estate sales.

Others are less interesting, or less specific and may just exist, as many had before, to round out the portfolio – Don Q from Puerto Rico makes a 151 to this day, and Tilambic from Mauritius does as well; El Dorado is re-introducing a new one soon (the Diamond 151, I believe), and Cruzan (Virgin Islands), Cavalier (Antigua), Bermudez (Dominican Republic), and Ron Carlos (USA) have their 151s of varying quality. Even Mhoba from South Africa joined the party in late 2020 with its own high ester version. The point is, even at such indifferent levels of quality, they’re not going anywhere, and if their heyday has passed us by, we should not think they have disappeared completely and can only be found, now, in out of the way shops, auctions or estate sales.

Because, somehow, they continue. They are still made. Young people with slim wallets continue to get wasted on this stuff, as they likely will until the Rapture. People post less and review 151s almost not at all, but they do post sometimes — almost always with wistful inquiries about where to get one, now that their last stock has run out and their favourite brand is no longer available. 151s might have run out of steam in the larger world of tiki, bartending and cocktails as new favourites emerge, but I don’t think they’ll ever be entirely extinct, and maybe that’s all that we can hope for, in a rum world as fast moving and fast changing as the one we have now.

Notes

- See my essay on proof

- Two other possibilities who could have developed a strong rum for HBC were Scheer and ED&F Man.

- Scheer was unlikely because they dealt in bulk, not their own brands, and mercantile shipping laws of the time would have made it difficult for them to ship rum to Britain or its colonies.

- ED&F Mann also did not consider itself a maker of branded rum, though it did hold the contract to supply the British Navy (Lemon Hart was their client, not a competitor). But by the mid to late 1800s and early 1900s, they already had diversified and became more of a major commodities supplier, so the likelihood of them bothering with developing a rum for HBC is minimal (assuming that line of thinking is correct

- I have a reference from the Parramatta Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate dated May 11, 1901 (Parramatta, NSW, Australia) that refers to a 33% Overproof Lowndes’ Rum, which, if using metric proofs, works out to 76% ABV exactly and also sheds light on how far back the Lownde’s brand name goes.

- I am indebted to the personal assistance of Martin Cate, Jeff “Beach Bum” Berry, Matt Pietrek, and the writings of Wayne Curtis, for some of the historical and conjectural detail of the early days of the 151s. Needless to say, any mistakes in this text or errors in the theories are mine, not theirs.

1970s Cruzan 151, used with kind permission of Jason Cammarata Sr.

The List

There is almost no rum company in existence which really cares much about its own release history and when its various rums were first issued, changed, reblended, remade, re-labelled, re-issued, nothing. Nor, since the demise of ReferenceRhum website, is there a centralized database of rums, to our detriment (though in 2022, Rum-X started to become a viable replacement). So one has to sniff around to find things, but at least google makes it easier.

There is a huge swathe of time between the 1930s and the 1990s, when rum was a seen as a commodity (referred to as merely “Jamaican” rum or “Barbados rum,” for example, in a generalized and dismissive context), and practically ignored as a quality product. Unsurprisingly records of the brands and rums were not often kept, so the list below is not as good as I’d like it to be. That said, here are those 151s I have managed to track down, and a few notes where applicable. I make no claim that it’s exhaustive, just the best I could do for now. I’d be grateful for any additions (with sources).

- Admiral’s Old J 151 Overproof Spiced Rum Tiki Fire

- Aristocrat 151

- AH Riise Old St Croix 151 (1960s; and from reddit page. A “St Croix Rum” was referred to in 1888 Bartender’s Guide without elaboration

- Appleton 151 (Jamaica)

- Ann’s Cove 151 Proof Barbados Rum (Discontinued, date unknown)

- Bacardi 151 Black (various production centres)

- Bacardi 151 (standard, discontinued 2016)

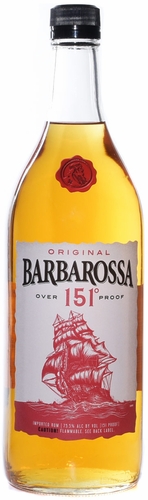

- Barbarossa 151 (USA)

- Bermudez 151 (Blanco and “standard”)(Dominican Republic)

- Barcelo 151 Proof (Dominican Republic)

- Bocoy 151 Superior Puerto Rican Rum

- Bounty 151 (St. Lucia)

- Black Beard’s Overproof 151

- Bocador 151

- Brugal 151 Blanco Overproof (Dominican Republic)

- Cane Rum 151 (Trinidad & Tobago)

- Carioca 151 (post Prohibition)

- Caribaya 151

- Castillo Ron Superior 151 Proof

- Cavalier 151 (Antigua)

- Cockspur 5-Star 151 Rum (Barbados, WIRD, Herschell Innis, made 1971-1974)

- Cohiba 151 (USA)

- Comandante 151 Proof Small Batch Overproof Rum (with orange peel)(Panama)

- Conch Republic Rum Co. 151 Proof (USA, Florida Distillers Co.)

- Coruba 151 (Jamaica)(74%)

- Cruzan 151 (2YO)(White and gold varieties) (US Virgin Islands)

- Cut to the Overproof (Spiced) Rum 75.5%

- Diamond Reserve Puncheon Demerara Rum 75.5% (Guyana)

- Diamond 151 (Guyana – 2020s)

- Don Q 151 (3YO blend)(at least since the 1960s)(Puerto Rico – Serralles)

- Don Cristobal 151 (Dominican Republic)

- Don Lorenzo 151 (Todhunter-Mitchell Distilleries, Bahamas, 1960s-1970s)

- El Dorado 151 (Guyana)(Re-issue 2020s)

- El Dorado Superior High Strength Rum (DDL USA Inc, 1980s)

- Explorer Fire Water Fine Island Rum 150 proof (St. Maarten, made by Caroni)

- Forres Park 151 Puncheon Overproof (Trinidad)

- Goslings Black Seal 151 (Bermuda)

- Hamilton 151 (Guyana/USA)(2014)

- Hamilton 151 “False Idol” (Guyana/USA)(2019)(85% Guyana 15% Jamaica pot still)

- Hana Bay Special 151 Proof Rum (Hawaii USA, post 1980s)

- Havana Club 151 (post Prohibition)

- Habitation Velier Forsythe 151 (Jamaica, WP)(2015 and 2017)

- Inner Circle Black Dot 33 Overproof Rum (Australia 1968-1986, pre-Beenleigh)

- James’s Harbor Caribbean Rum 151

- Lamb’s Navy Rum 151 (UK, blend of several islands)

- Largo Bay 151

- Lemon Hart 151 (possibly since late 1880s, early 1890s) (Guyana/UK)(several editions exist)

- Lost Spirits Cuban Inspired 151 (USA)(2010s)(Limited)

- Mhoba Strand 151º (South Africa)(High Ester, Glass-Cask blend)

- Monarch Rum 151 Proof (Monarch Import Co, OR, USA – Hood River Distillers)

- Mount Gay 151 (Barbados)

- Old Nassau 151 Rum (Bahamas)

- Old St. Croix 151 Rum (A.H. Riise)(long discontinued)..

- Palo Viejo 151 Ron de Puerto Rico (Barcelo Marques & Co, Puerto Rico – Serralles)

- Paramount “El Caribe” 151 Rum (US Virgins Islands )

- Paramount “West Indies Flaming Rum” 151 (US Virgin Islands)

- Portobelo 151º Superior Rum (Panama)

- Potter’s Superior West Indies Rum 151

- Puerto Martain Imported West Indies Rum (75.5%)(Montebello Brands, MD USA)

- Pusser’s 151 (British Virgin Islands)

- Ron Antigua Special 151 Proof (US Virgin Islands, LeVecke Corporation)

- Ron Diaz 151 (Puerto Rico / USA)

- Ron Carlos 151 (Puerto Rico / USA)(Aged min of 1 yr)

- Ron Corina 151 (USA, KY)

- Ron Cortez Dry Rum 151 (Panama)

- Ron Matusalem 151 Proof “Red Flame” (Bahamas, 1960s-1970s)

- Ron Rey 151 (post Prohibition)

- Ron Palmera 151 (Aruba)

- Ron Rico 151 (Puerto Rico)(post-1968 a Seagrams brand, marketed in 1970s in Canada; bought by Serralles in 1985)

- Ron Ricardo 151 (Bahamas) from before 2008

- Ron Roberto 151 Superior Premium Rum (Puerto Rico / USA)

- Three Dagger 10YO Jamaica Rum (J. Wray & Nephew), 151 proof (1950s)

- Tilambic 151 (Mauritius)

- Tortuga 151 Proof Cayman Rum (1980s-1990s)

- Trader Jim West Indies Rum 151

- Trader Vic’s 151 Proof Rum (World Spirits, USA)

Sources

Some rum list resources

Bacardi’s discontinuing the 151

Don the Beachcomber, recipes, the rise of Tiki and post-Prohibition times

Cocktails

Other bit and pieces

Colour – Very dark brown

Colour – Very dark brown It sounds strange to say it, but the

It sounds strange to say it, but the

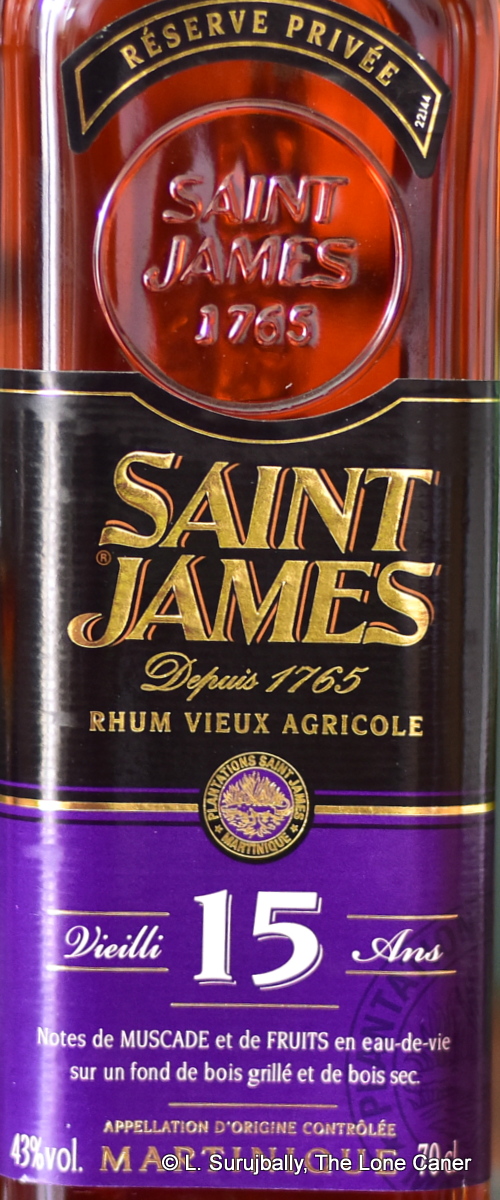

Because that 15 year old rhum is, to my mind, something of an underground, mass-produced steal. It has the most complex nose of the “regular” lineup, and also, paradoxically, the lightest overall profile — and also the one where the grassiness and herbals and the cane sap of a true agricole comes through the most clearly. It has the requisite crisp citrus and wet grass smells, sugar came sap and herbs, and combines that with honey, the delicacy of white roses, vanilla, light yellow fruits, green grapes and apples. You could just close your eyes and not need ruby slippers to be transported to the island, smelling this thing. It’s sweet, mellow and golden, a pleasure to hold in your glass and savour

Because that 15 year old rhum is, to my mind, something of an underground, mass-produced steal. It has the most complex nose of the “regular” lineup, and also, paradoxically, the lightest overall profile — and also the one where the grassiness and herbals and the cane sap of a true agricole comes through the most clearly. It has the requisite crisp citrus and wet grass smells, sugar came sap and herbs, and combines that with honey, the delicacy of white roses, vanilla, light yellow fruits, green grapes and apples. You could just close your eyes and not need ruby slippers to be transported to the island, smelling this thing. It’s sweet, mellow and golden, a pleasure to hold in your glass and savour

To some extent, it has a lighter nose than the luscious

To some extent, it has a lighter nose than the luscious

Others are less interesting, or less specific and may just exist, as many had before, to round out the portfolio – Don Q from Puerto Rico makes a 151 to this day, and

Others are less interesting, or less specific and may just exist, as many had before, to round out the portfolio – Don Q from Puerto Rico makes a 151 to this day, and

1423, the Danish indie, has taken this concept a step further with their 2019 release of a Brazil / Barbados carnival — it comprised of 8- and 3-year old Foursquare rums (exact proportions unknown, both column still) to which was added an unaged cachaca from Pirassununga (they make the very popular “51” just outside Sao Paolo), and the whole thing left to age for two years in Moscatel wine casks for two years, before being squeezed out into 323 bottles at 52% ABV.

1423, the Danish indie, has taken this concept a step further with their 2019 release of a Brazil / Barbados carnival — it comprised of 8- and 3-year old Foursquare rums (exact proportions unknown, both column still) to which was added an unaged cachaca from Pirassununga (they make the very popular “51” just outside Sao Paolo), and the whole thing left to age for two years in Moscatel wine casks for two years, before being squeezed out into 323 bottles at 52% ABV.

I should begin by warning you that this rum is sold on a very limited basis, pretty much always to favoured bars in the Philippines, and then not even by the barrel, but by the bottle from that barrel – sort of a way to say “Hey look, we can make some cool sh*t too! Wanna buy some of the other stuff we make?”. Export is clearly not on the cards…at least, not yet.

I should begin by warning you that this rum is sold on a very limited basis, pretty much always to favoured bars in the Philippines, and then not even by the barrel, but by the bottle from that barrel – sort of a way to say “Hey look, we can make some cool sh*t too! Wanna buy some of the other stuff we make?”. Export is clearly not on the cards…at least, not yet.

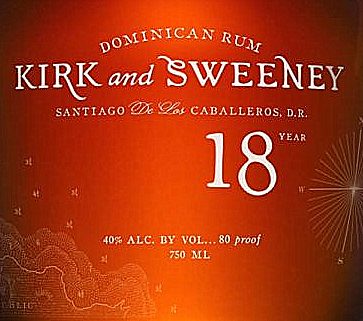

This is not to say that there isn’t some interesting stuff to be found. Take the nose, for example. It smells of salted caramel, vanilla ice cream, brown sugar, a bit of molasses, and is warm, quite light, with maybe a dash of mint and basil thrown in. But taken together, what it has is the smell of a milk shake, and there doesn’t seem to be much in the way of startling originality – not exactly what 18 years of ageing would give you, pleasant as it is. It’s soft and easy, that’s all. No thinking required.

This is not to say that there isn’t some interesting stuff to be found. Take the nose, for example. It smells of salted caramel, vanilla ice cream, brown sugar, a bit of molasses, and is warm, quite light, with maybe a dash of mint and basil thrown in. But taken together, what it has is the smell of a milk shake, and there doesn’t seem to be much in the way of startling originality – not exactly what 18 years of ageing would give you, pleasant as it is. It’s soft and easy, that’s all. No thinking required.

Colour – Amber

Colour – Amber

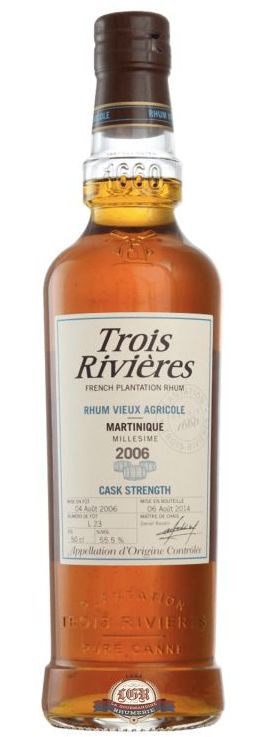

The Trois Rivières Brut de fût Millésime 2006 (which is its official name) is relatively unusual: it’s aged in new American oak barrels, not Limousin, and bottled at cask strength, not the more common 43-48%. And that gives it a solidity that elevates it somewhat over the standards we’ve become used to. Let’s start, as always, with the nose — it just becomes more assertive, and more clearly defined…although it seems somehow gentler (which is quite a neat trick when you think about it). It is redolent of caramel and vanilla first off, and then adds green apples, tart yoghurt, pears, white guavas, watermelon and papaya, and behind all that is a delectable series of herbs – rosemary, dill, even a hint of basil and aromatic pipe tobacco.

The Trois Rivières Brut de fût Millésime 2006 (which is its official name) is relatively unusual: it’s aged in new American oak barrels, not Limousin, and bottled at cask strength, not the more common 43-48%. And that gives it a solidity that elevates it somewhat over the standards we’ve become used to. Let’s start, as always, with the nose — it just becomes more assertive, and more clearly defined…although it seems somehow gentler (which is quite a neat trick when you think about it). It is redolent of caramel and vanilla first off, and then adds green apples, tart yoghurt, pears, white guavas, watermelon and papaya, and behind all that is a delectable series of herbs – rosemary, dill, even a hint of basil and aromatic pipe tobacco.

Okay so, on to palate. Straw yellow in the glass, it was softer and less intense, which, for a forty percenter, was both good and bad. Here the grassy and herbal notes took on more prominence, as did citrus, some tart unsweetened yoghurt, honey and cane juice. The youth was evident in the slight sharpness and lack of real roundness – the two years of ageing had

Okay so, on to palate. Straw yellow in the glass, it was softer and less intense, which, for a forty percenter, was both good and bad. Here the grassy and herbal notes took on more prominence, as did citrus, some tart unsweetened yoghurt, honey and cane juice. The youth was evident in the slight sharpness and lack of real roundness – the two years of ageing had  In 1923 La Mauny was sold to Théodore and Georges Bellonnie who enlarged and brought in new facilities such as a distillation column, new grinding mills and a steam engine. The distillery expanded hugely thanks to increased output and good marketing strategies and La Mauny rhums began to be exported around 1950. In 1970, after the Bellonnie brothers had both passed away, the Bordeaux traders and old-Martinique family of Bourdillon teamed up with Théodore Bellonnie’s widow and created the BBS Group. The company grew strongly, launching on the French market in 1977. Jean Pierre Bourdillon, who ran the new group, undertook to modernize La Mauny. He began by reorganizing the fields in order to make them accessible to mechanical harvesting and built a new distillery in 1984 (with a fourth mill, a three column still and a new boiler) a few hundred meters from the old one, increasing the cane crushing capacity and buying the equipment of the Saint James distillery in Acaiou, unused since 1958.

In 1923 La Mauny was sold to Théodore and Georges Bellonnie who enlarged and brought in new facilities such as a distillation column, new grinding mills and a steam engine. The distillery expanded hugely thanks to increased output and good marketing strategies and La Mauny rhums began to be exported around 1950. In 1970, after the Bellonnie brothers had both passed away, the Bordeaux traders and old-Martinique family of Bourdillon teamed up with Théodore Bellonnie’s widow and created the BBS Group. The company grew strongly, launching on the French market in 1977. Jean Pierre Bourdillon, who ran the new group, undertook to modernize La Mauny. He began by reorganizing the fields in order to make them accessible to mechanical harvesting and built a new distillery in 1984 (with a fourth mill, a three column still and a new boiler) a few hundred meters from the old one, increasing the cane crushing capacity and buying the equipment of the Saint James distillery in Acaiou, unused since 1958.