As the memories of the seminal and ground breaking Demeraras fade and the Caronis climb in price past the point of reason, and the smaller outturns of Velier’s limited editions vanish from our sight, it is good to remember the third major series of rums that Velier has initiated, which somehow does not get all the appreciation and publicity so attendant on the others, or climb in price so rapidly on secondary markets.

This is the Habitation Velier collection, which to my mind has real potential of joining the pantheon of Caronis and those near-legendary Guyanese rums which are so firmly anchored to the Genoese company of Velier’s reputation. And I advertise the importance of the series in this fashion because its uniqueness tends to fly under the radar – they’re seen as secondary efforts released by a major house, and take third or fourth place in most people’s estimation, behind other more famous “black bottle” series. Sometimes they’re even seen as repositories for leftover stuff that Velier has in stock that would not fit any of the other limited editions – Warren Khong, 70th Anniversary, Indian Ocean Stills, Villa Paradisetto, Hampdens, and so on. Mitch Wilson, introducing Luca in a May 2020 interview, didn’t even see fit to mention them as something special.

But they are. And I contend that ignoring them or relegating them to also-ran status would be denying their importance and does them a disservice – the Habitation line is really quite special on a number of fronts. For, consider these points:

The thirty releases of the collection (so far, as of 2020) remain a world class showcase for pot still expressions only, and no bottler – producer or independent, ever – has taken a chance on focusing so clearly and significantly on just this one specific segment of rums. And, unlike most independent bottlers who release distillate made on no-matter-what-still, let’s-just-take-a-good-barrel, this series eschews both the still/barrel point of view or the geographical specificity of the Demeraras and Caronis, and it takes as its subject matter pot rums from anywhere (Jamaica, Barbados, Guyana, Marie Galante, USA, South Africa, Seychelles), issuing both aged and unaged rums…often from major houses who have never released such rums themselves. Best of all, the damned things are just fine, the quality remains high, and in a time of ever increasing prices, they have stayed relatively affordable (though still pricey in comparison to a standard rum from any of the representative distilleries – in this they fail the Stewart Affordability Conjecture).

The question is, why did Velier bother? It’s not as if many of these rums or producers are unknown and indies have put out pot still rums for ages (alongside much other good hooch). Why create an entirely separate brand for this stuff, a new series of bottles, an entirely new design look?

Luca Gargano, the boss of Velier, speaks of a time as recently as 2013 (at the time he was just introducing his own system but it had not gained much traction yet) — when in the confusion of the rum world regarding classifications, too much rum was lumped into the class of agricoles, and a catchall category of “rum” that encompassed everything else. But in that huge collective bucket were many different kinds, including artisanal, small batch rums, “the equivalent of pure single malts.” He envisioned Habitation Velier as a separate branch of his company which would focus exclusively on this subset but made with less fuss and bother and priced more reasonably than the already escalating major bottlings he was getting known for.

My own feeling is also that he followed the same principle he had with his occasional off-hand one-offs like the Basseterres or the Courcelles, or the original Damoiseau 1980 – he was enthusiastic about them and wanted to show them off (as I have rather wryly observed before, sometimes that’s all it takes, with him). Plus, I’m convinced that he also had some unusual pot still distillate on hand — from Barbados, Guyana, Worthy Park and Marie Galante, etc — and perhaps felt that releasing them as individual black bottles wouldn’t cut it [see note 1]. The Haitian clairins and the Capovilla collaborations were established with their own distinct looks, and those lines served their own specific purposes, so it made sense to start from scratch and go with a completely new design for a set of rums which could be launched and expanded on in future years, that would concentrate on the uniqueness of pot stills, and include first run rum from new estate distilleries (he was already negotiating with Hampden [see note 2] for their distillate at the time).

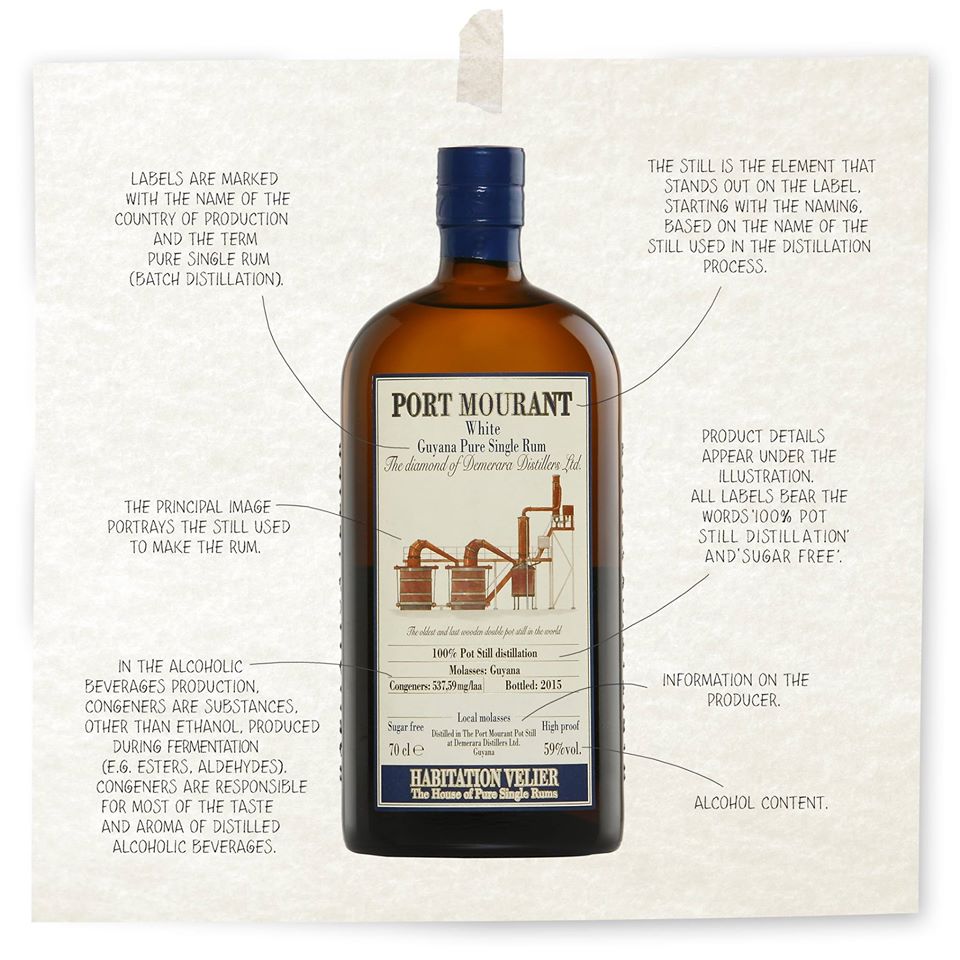

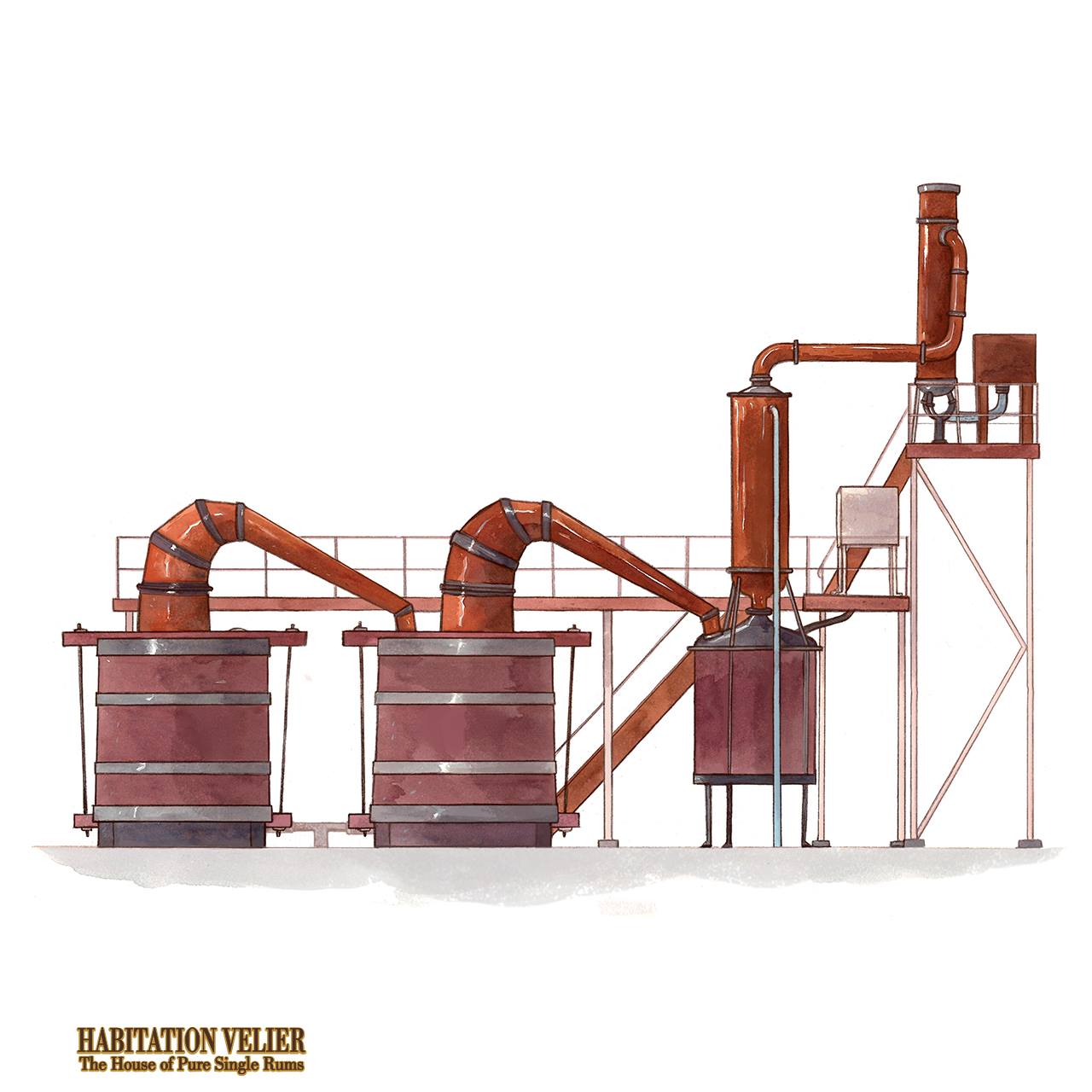

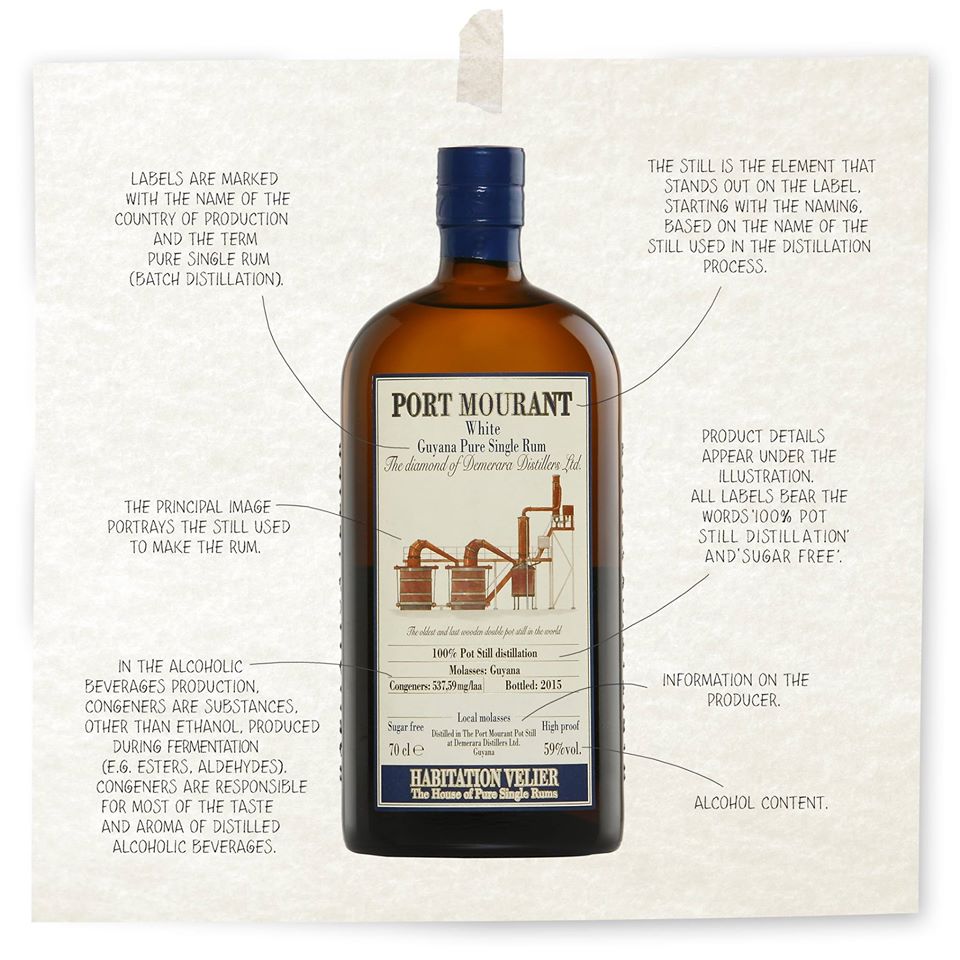

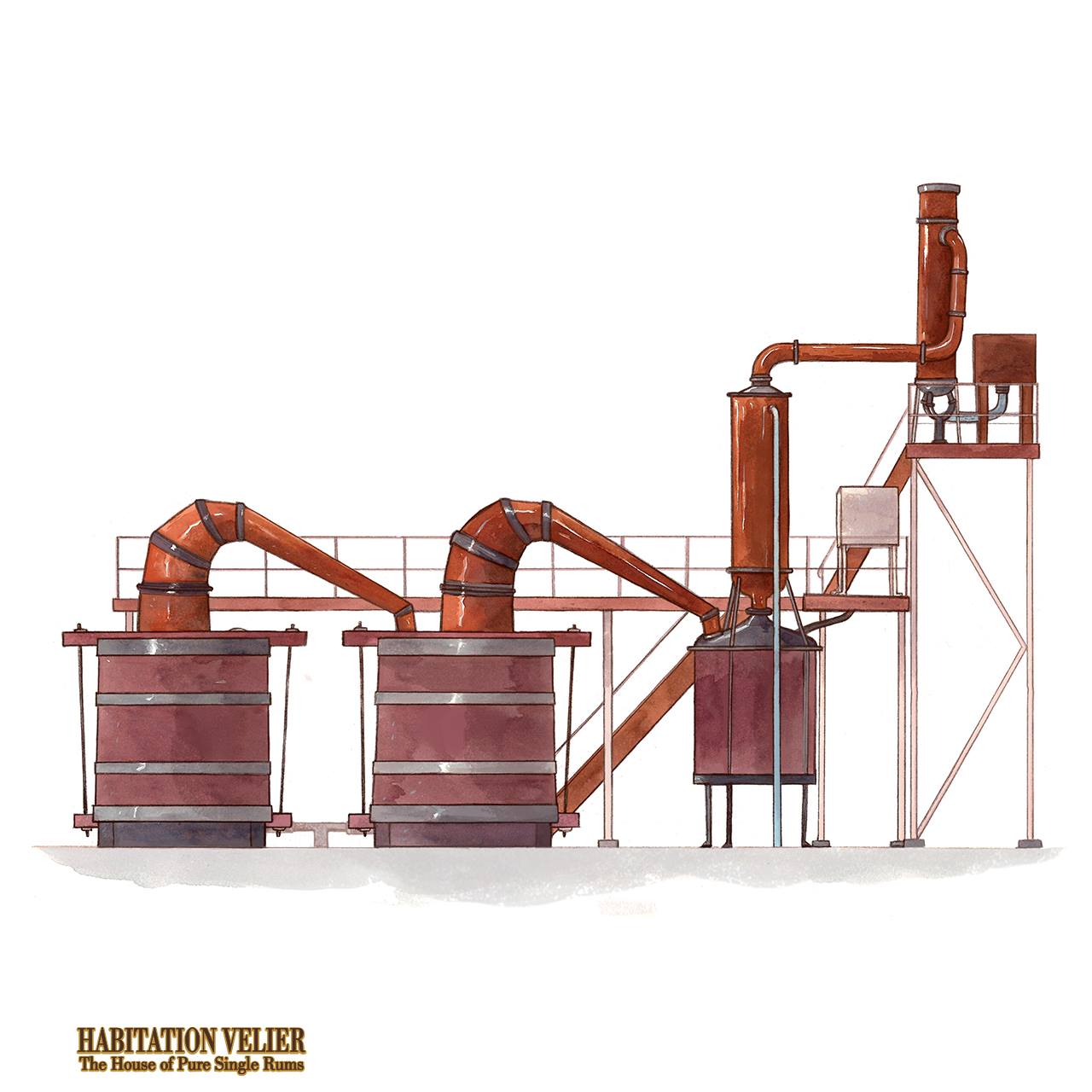

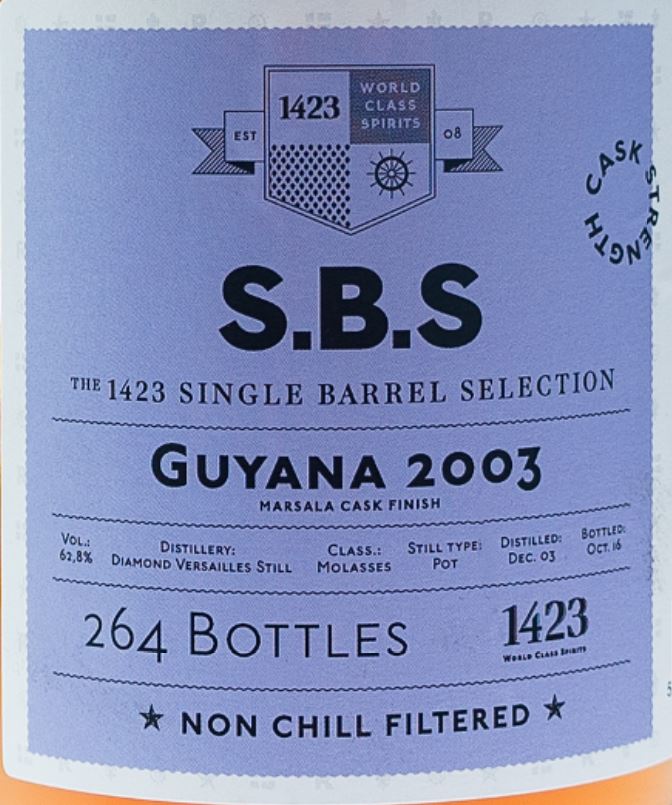

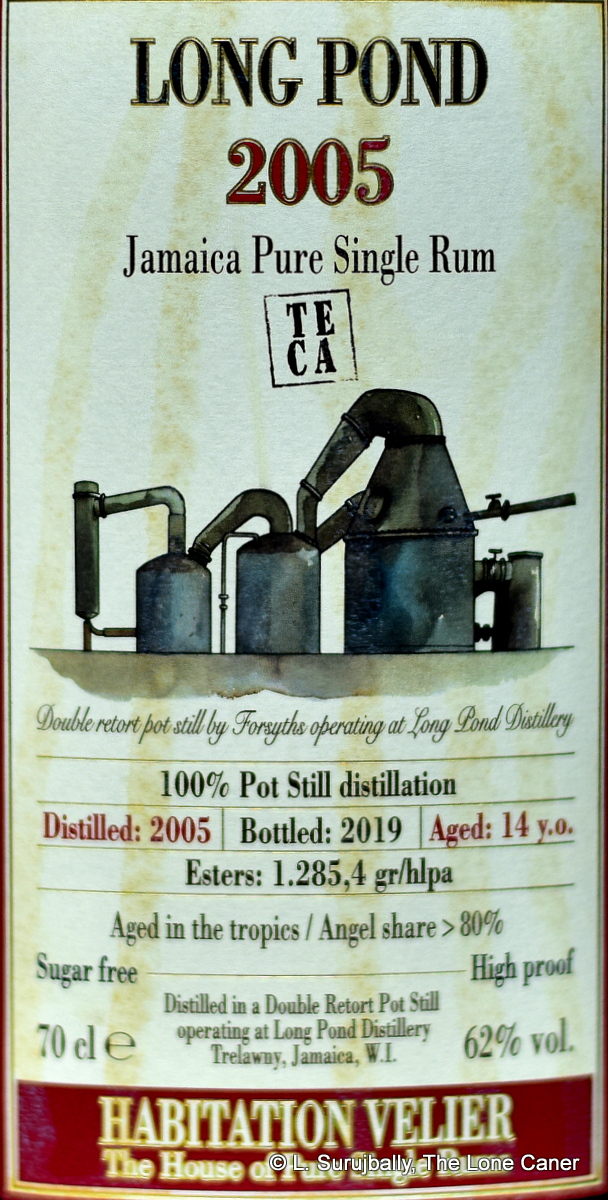

The result was a series as distinctive as any previously issued, which channelled much of the same individualistic design ethos as the classics. They were flat 70cl bottles, dark ones for aged rums, transparent for white unaged ones to start (not consistently, but often). They had that subtle hip flask vibe, where you almost felt you could put it in your back pocket like a flattie of old and nip at it for the rest of the day. The labelling was even better than the Demeraras of the Age (my opinion only) — those original ones almost redrew the labelling map with their near unprecedented level of detail (the name of the distillery, the dates of make, the still, the strength, the outturn) but the proposed Habitation Velier design would provide more, much more.

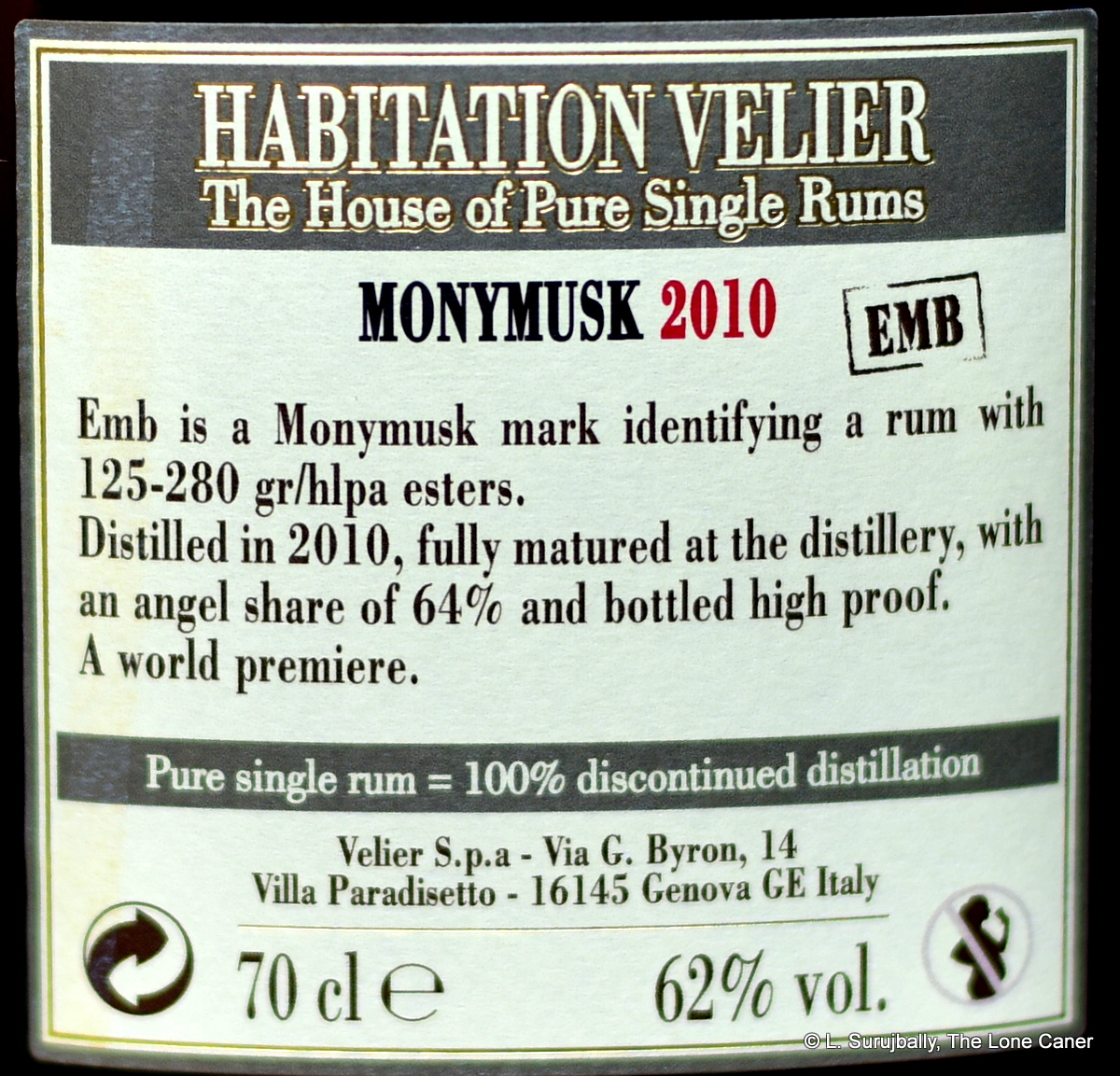

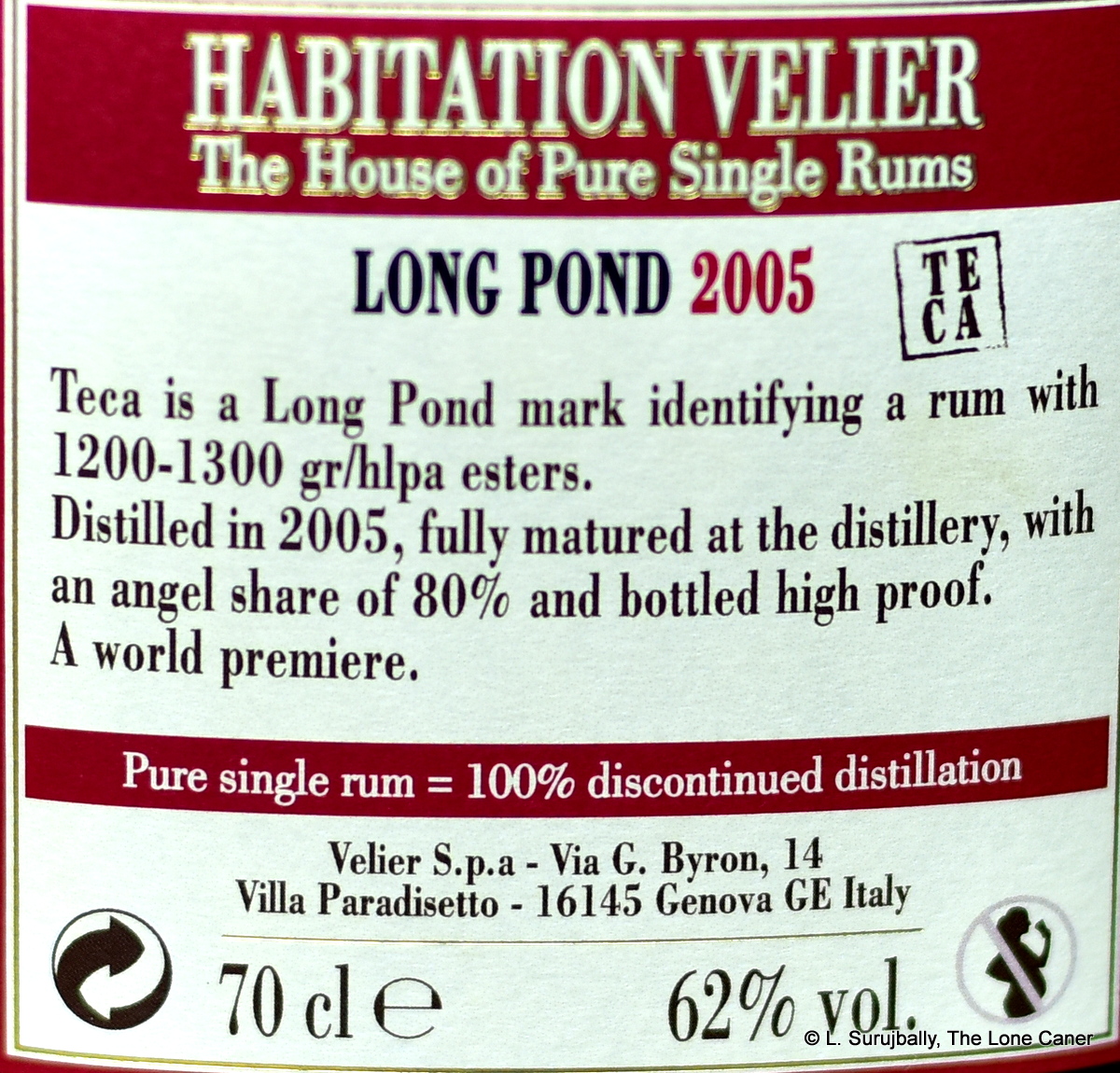

For example not only did you get all that, but you were told of the distillate source, the ester or congener level (a geek godsend, surely), its sugar free nature, and were treated to a beautifully rendered watercolour of the original pot still that made it, plus some words on that still, and as if that weren’t enough, where it was aged (tropics) and the angel’s share. In point of fact, the only thing missing here was the bottle outturn, which strikes me as an almighty curious omission given Luca’s mania for providing more rather than less. But when I touched base with him to ask that specific question, he said it had been a deliberate decision, so as to prevent the bottles becoming collector’s items and having the street price rise beyond all sanity in flippers’ and speculators’ hands on the secondary market(see note 3).

Luca Gargano has been a fixture on the rum world for so long that people don’t always remember that there was a time when he was a smallish importer, and “just” another newb indie bottler with odd, even controversial, ideas and his rums were considered obscure and too expensive. These days his name is known everywhere rums are drunk (and collected). But paradoxically, it’s gotten to the point where the generation of rum drinkers who have emerged in the last five years don’t remember the seminal nature of his earlier work, just see the currently available ones, and I was asked in mystification just the other week “What Demerara rums?” by a man whose memories begin with Caroni and move into the Hampdens and Habitations. To some extent the HV line allows them to participate in the uniqueness of some of Velier’s early work and ethos… but without paying four figures for the privilege.

Luca Gargano has been a fixture on the rum world for so long that people don’t always remember that there was a time when he was a smallish importer, and “just” another newb indie bottler with odd, even controversial, ideas and his rums were considered obscure and too expensive. These days his name is known everywhere rums are drunk (and collected). But paradoxically, it’s gotten to the point where the generation of rum drinkers who have emerged in the last five years don’t remember the seminal nature of his earlier work, just see the currently available ones, and I was asked in mystification just the other week “What Demerara rums?” by a man whose memories begin with Caroni and move into the Hampdens and Habitations. To some extent the HV line allows them to participate in the uniqueness of some of Velier’s early work and ethos… but without paying four figures for the privilege.

I have come to the conclusion that the impressive rums of the house, coupled with Luca’s uncompromising perception of what he terms a pure rum, often overshadows an aspect of his character not often discussed, and that’s the one of an educator. I know of no other rum maker in the world who so consistently releases rums that under normal circumstances have almost no possibility of being big sellers or future grail quests, but does so simply because they interest him and he wants to show off their qualities to interested rum chums, and maybe just because he damn’ well can. Daniele Biondi in an August 2020 round-table discussion, remarked on a similar point relating to Velier’s desire to always present something unique and different with the HV line, even from established distilleries whose work we know quite well.

Such rums were the Guyanese La Bonne Intention (LBI) rums from 1995 and 1998; the Indian Ocean stills’ rums; the Basseterre 1995 and 1997, the Courcelles 1972, the 2019 NRJ quartet with that growly beast of the TECA, or even the granddaddy of them all, the original fullproof Damoiseau 1980 which he released so nervously. And ask yourself, who on earth, which casual drinker, would ever buy the quartet of the Monymusk EMB and MMW Tropical vs Continental Ageing — which would certainly not appeal to anyone for their price — given what they were issued to achieve? Any one of these other rums could be seen as emblematic of Luca’s desire to showcase aspects of imperfectly demonstrated or understood rumlore. But what has in fact happened to them is that those one-offs appeal to the micro-segment of rumgeeks and deep divers, not the greater rum drinking population at large who are enamoured of great names like Port Mourant and Hampden and Foursquare…but not so much the smaller ones.

The HV series, then, are perhaps more aimed at that midrange bunch of relatively knowledgeable drinkers, influencers and anoraks, rather than for some high priced connoisseur’s market (where money but not knowledge is more often the real coin of the realm) or the deep-diving über-dorks (where exacting command of micro-detailed minutiae is). They are, in that sense, a useful bridge between more commonly appreciated rums, and those that require a bit more experience, perhaps, to fully appreciate — and can therefore be had and enjoyed and argued over by both long-time aficionados and new-to-the-club rumgeek wannabes.

The HV series, then, are perhaps more aimed at that midrange bunch of relatively knowledgeable drinkers, influencers and anoraks, rather than for some high priced connoisseur’s market (where money but not knowledge is more often the real coin of the realm) or the deep-diving über-dorks (where exacting command of micro-detailed minutiae is). They are, in that sense, a useful bridge between more commonly appreciated rums, and those that require a bit more experience, perhaps, to fully appreciate — and can therefore be had and enjoyed and argued over by both long-time aficionados and new-to-the-club rumgeek wannabes.

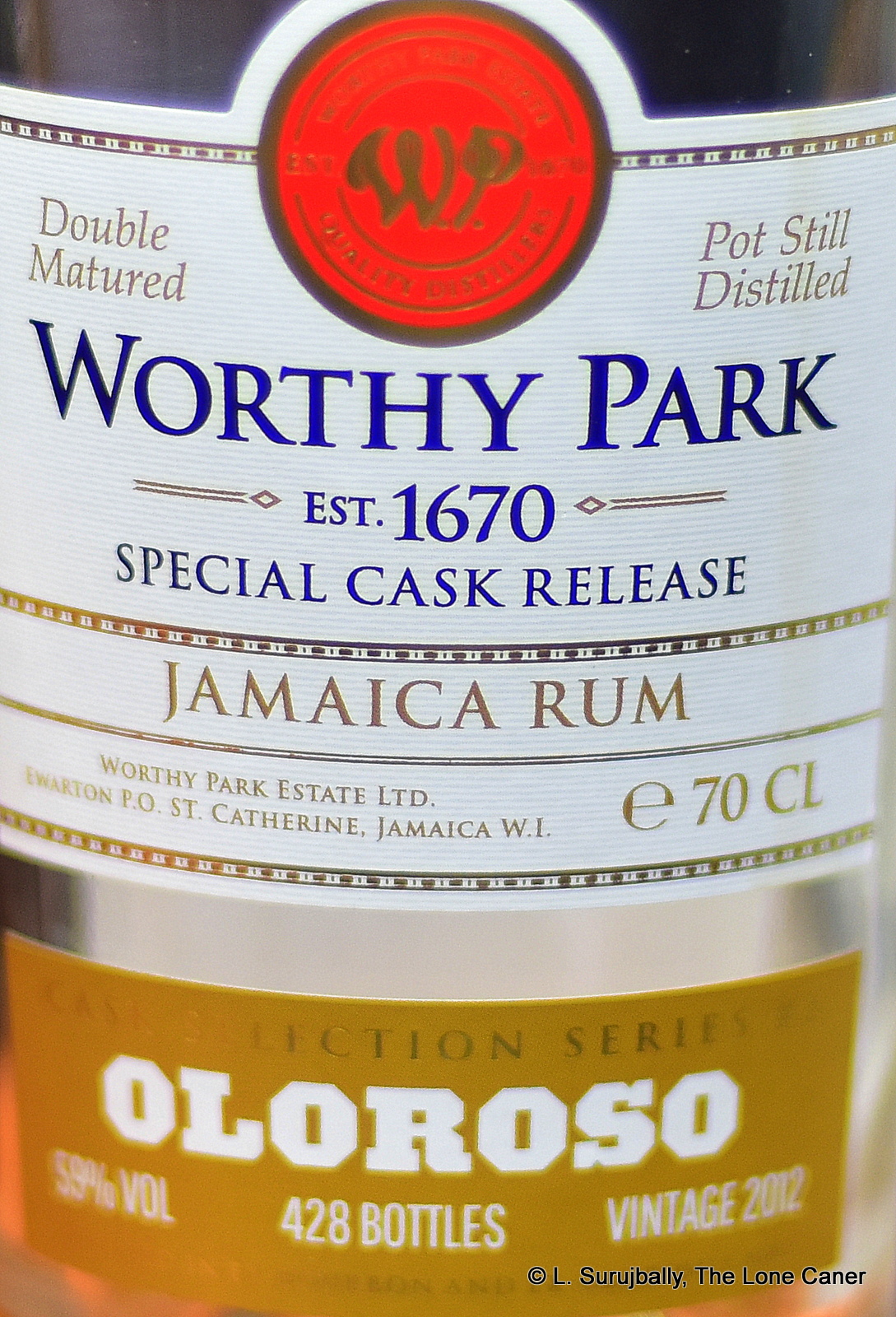

Lastly, there’s the impressive amount of “firsts” which the HV line has demonstrated: as noted, they were completely distillery-aged pot-still rums, many never seen or released before (like the Foursquare 2013); the first estate bottling from Worthy Park (2005) and the only WPM (2006) mark bottled to date; first Hampden marks like HLCF, OWH, LROK, HGML, LFCH, DOK; first vintage Mount Gay pot still (Last Ward); first PM unaged unfiltered white from Guyana…and so on. I mean, say what you will and disagree if you must, but that’s quite an accomplishment for any rum maker to produce in such quantity, so quickly.

Taking all this into account, the Habitation Velier range is, in my opinion, near unique – a major, wide-ranging series of paradoxically specific rums, to be seen as such. Aside from the common thread of their pot still origins, there’s little to tie them together. They span the gamut of all rums, all countries, all styles, all ages, all strengths and will only expand as the years pass. There’s hardly a weak one in the bunch, and some are simply stunning. One day I can even see them being reference rums, enabling people to get a grip on regional pot still profiles from around the world.

Of course, picking out any single one of them as a representative of all is an exercise in futility — everyone has a favourite, a preferred vintage, a personal pet love in the line, and this relates directly to the intersection of broad range, amazing variety and needs-a-little-effort approachability. Somehow this one line of rums, overlooked and sometimes even dismissed in favour of Veliers’ more famous limited editions, presses way more buttons than initially seems to be the case, and only grows in stature with time. I deem them not only Key Rums Of the World when considered as a class…but also among the most important series of rums ever made.

Other Notes

- In a promotional video interview posted in 2019 but surely made before that year, Luca spoke about the HV rums; originating philosophy, and the original Habitation Velier rums were on display in the now famous black bottles, with special multicoloured “classic” labels. These designs were never implemented, and were released as standalone black bottles, though still labelled as HV for some reason.

- When the Hampden rums started to come on the market in 2016-2017, the best part of the ageing crop was siphoned off to Velier’s “dark bottle range” (my term, not theirs), as a consequence of their perhaps being perceived as more premium. But this has not lessened the stature of those selected for the HV series and while their value has grown – the June 2020 RumAuctioneer auction had the Hampden HGML 2010-2019 9 YO finish up at £230 for example – quite an appreciation over the original price.

- Initially when I wrote the post, I had the outturn of quite a few releases of the range, and in line with Luca’s desire not to promote speculation, I elected not to publish them. However, since the webpage on Velier’s site now provides this information as of October 2021, I have added it to my listings.

- There are links to only seven rums whose reviews have been published here, to 2020. More exist and are planned for publication soon, enough to allow me to justify the whole line as an inclusion in the Key Rums series.

- Photos taken from and used courtesy of Velier and Habitation Velier facebook pages and official websites. I messaged Luca directly for some of the background details. Note that in October 2021, Velier’s website dedicated a page to all the releases so there’s a complete label reference there for the curious.

Habitation Velier Rums – By Country

Seychelles

- Takamaka Seychelles Pure Single Rum 3 YO (2018-2021) 60.8% (1150b)

- Takamaka Seychelles Pure Single Rum Blanc (2020 Unaged) 69% (1200b)

South Africa

- Mhoba South Africa Pure Single Rum 4 YO (2017-2021) 64.6% (1445b)

Reunion

- Savanna Reunion Pure Single Rum White HERR (2018) 62.5% (2784b)

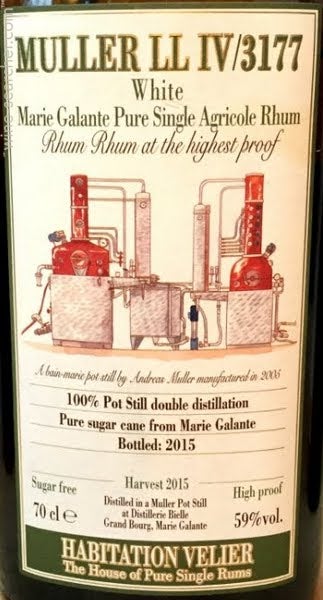

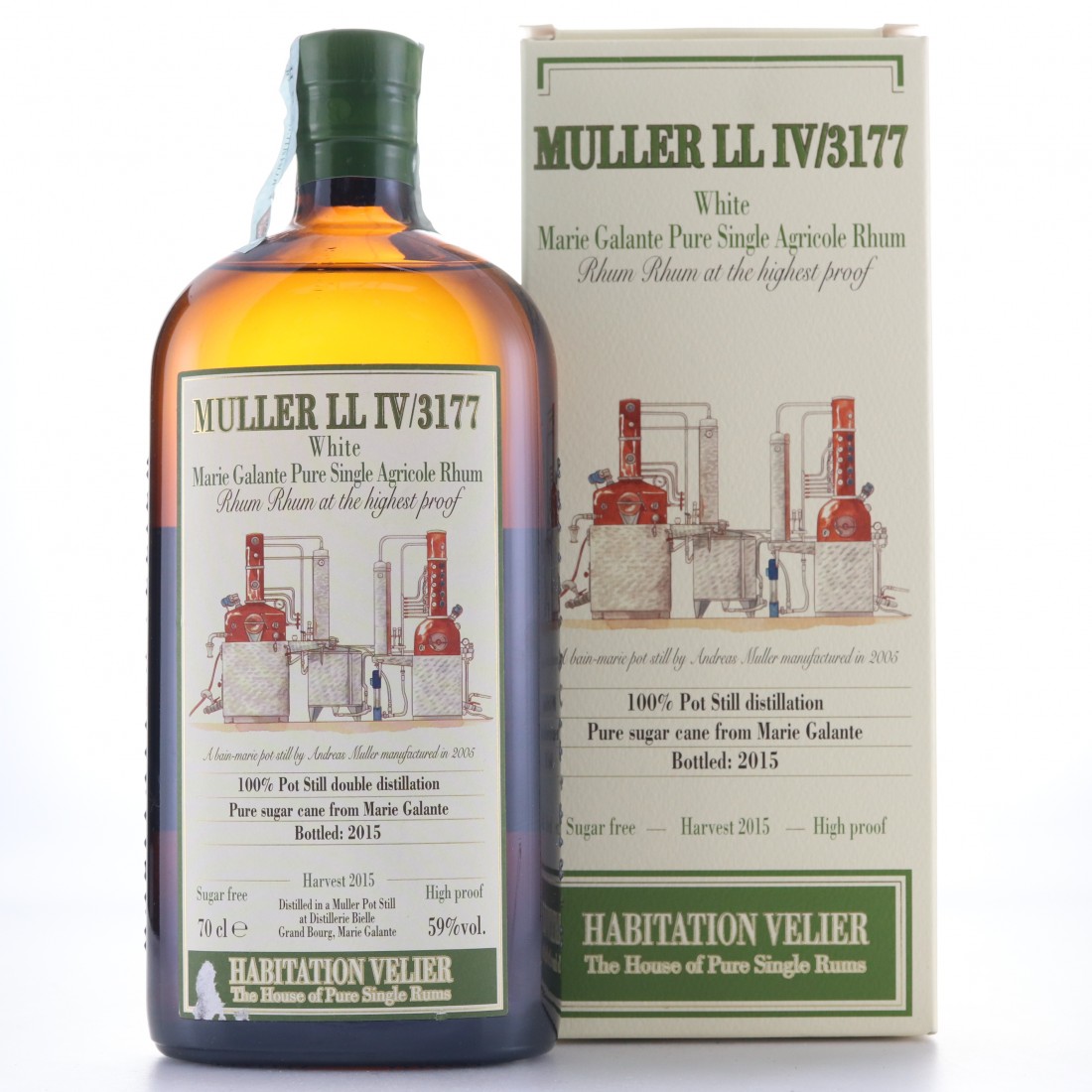

Marie Galante

India

Guyana

USA

Barbados

Jamaica

- Hampden Jamaica Pure Single Rum 6YO LROK (2010-2016) 67% (5292b)

- Hampden Jamaica Pure Single Rum 6YO HLCF (2010-2016) 68.5% (5364b)

- Hampden Jamaica Pure Single Rum 6YO LROK-HLCF (2010-2016) 60% (LMDW 60th Anniv)(243b)

- Hampden Jamaica Pure Single Rum <>H White (2018)(Whisky Live Paris) 66% (236b)

- Hampden Jamaica Pure Single Rum LROK White (2018) 62.5% (2148b)

- Hampden Jamaica Pure Single Rum 9 YO HGML (2010-2019) 62% (800b)

- Hampden Jamaica Pure Single Rum 7 YO LFCH (2011-2018) 60.5% (7056b)

- Hampden Jamaica Pure Single Rum 10 YO C<>H (2010-2020) 68.5% (1215b)

- Hampden Jamaica Pure Single Rum 10 YO LROK (2010-2020) 62%

- Hampden Jamaica Pure single Rum 5 YO OH (2016 – 2021) 62% (2536b)

- Hampden Jamaica Pure Single Rum 3 YO HES (2019-2022) 60.5% (620b)

- Hampden Jamaica Pure Single Rum 5 YO DOK (2017-2022) 60.5% (1800b)

- Hampden Jamaica Pure Single Rum 9 YO (2010-2019) LROK 63.2% (Salon du Rhum)(247b)

- Hampden Jamaica Pure Single Rum 9 YO (2010-2019) HLCF/DOK 61% (The One & Only)(251b)

- Hampden Jamaica Pure Single Rum 9 YO (2010-2019) <H> 69.2% (LMDW)(158b)

- Hampden Jamaica Pure Single Rum 8 YO (2011-2019) OWH 59.5% (Berlin Bar Convent)(274b)

- Hampden Jamaica Pure Single Rum 8 YO (2011-2018) LFCH 61.7% (Whisky Live Singapore 2019)(254b)

- Hampden Jamaica Pure Single Rum 7 YO (2012-2019) OWH 62.8% (Whisky Live Paris 2019)(263b)

- Monymusk EMB 2010-2019 9 YO (2019) 62% (2529b)

- Monymusk EMB 248 Jamaica Pure Single Rum White (2015), 59%

- Momymusk MMW Jamaica Pure Single Rum 7 YO (2015-2022) 59% (1500b)

- Monymusk Jamaica Single Rum 8 YO EMB ex-Bourbon No.1 (2014-2022) 60% (202b)

- Monymusk Jamaica Single Rum 8 YO EMB ex-Bourbon No.2 (2014-2022) 60% (233b)

- Monymusk Jamaica Single Rum 7 YO MMW ex-Bourbon No.818 (2015-2022) 59% (283b)

- Monymusk Jamaica Single Rum 7 YO MMW ex-Bourbon No.960 (2014-2022) 60% (281b)

Habitation Velier Rums – By Year of Bottling

2015

- Muller LL IV / 3177 Pure Single Agricole Rhum White (Marie Galante) (2015) 59%

- Port Mourant Still Guyana Pure Single White Rum (2015), 59.0%

- Foursquare Pot Still Barbados Pure Single Rum 2 YO (2013-2015), 64%

- Foursquare Pot Still Barbados Pure Single White Rum (2015) 59%

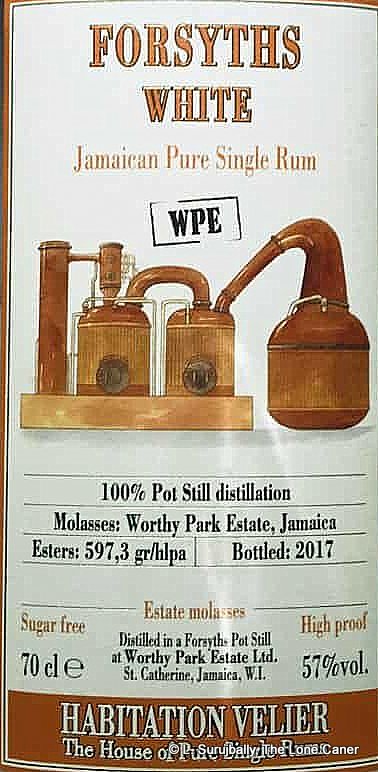

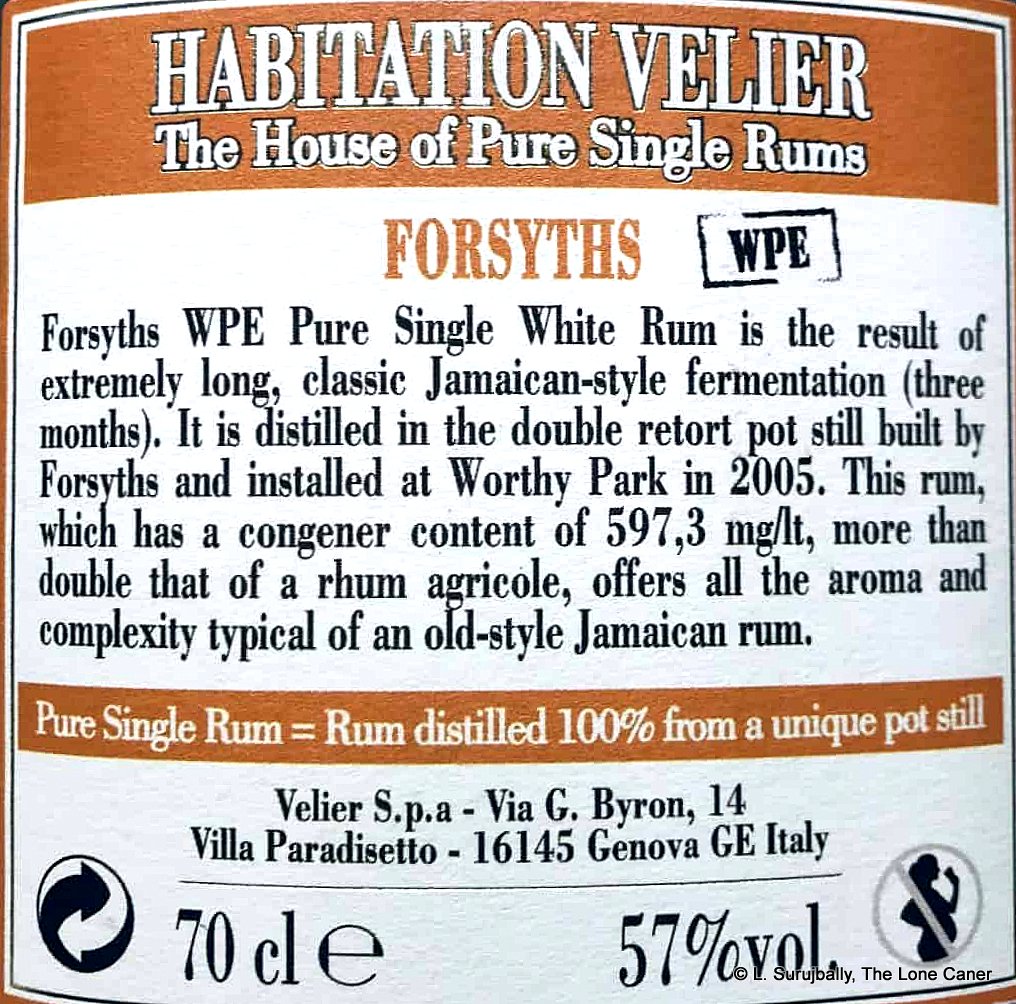

- WP Forsyths Pot Still Jamaica Pure Single Rum 10 YO (2005-2015), 57.8%

- WP Forsyths Pot Still 502 Jamaica Pure Single White Rum (2015), 57%

- WP Forsyths 151 Proof Jamaica Pure Single White Rum (2015), 75.5%

- Monymusk EMB 248 Jamaica Pure Single Rum White (2015), 59%

2016

- Hampden Jamaica Pure Single Rum 6YO LROK (2010-2016) 67%

- Hampden Jamaica Pure Single Rum 6YO HLCF (2010-2016) 68.5%

- Hampden Jamaica Pure Single Rum 6YO LROK-HLCF (2010-2016) 60% (LMDW 60th Anniv)

2017

- Last Ward (Mount Gay) Barbados Pure Single Rum 10 YO (2007-2017) 59%

- WP Forsyths Pot Still Jamaica Pure Single Rum (WPM) 11 YO (2006-2017), 57.5%

- WP Forsyths Pot Still Jamaica Pure Single Rum White (WPE) (2017), 57%

- WP Forsyths 151 Proof Jamaica Pure Single White Rum (2017), 75.5%

- WP Worthy Park Jamaica Pure Single Rum 10 YO (2007-2017) 59%

2018

- Savanna Reunion Pure Single Rum White HERR (2018) 62.5%

- Last Ward (Mount Gay) Barbados Pure Single Rum 9 YO (2009-2018) 59%

- Hampden Jamaica Pure Single Rum <>H White (2018)(Whisky Live Paris)

- Hampden Jamaica Pure Single Rum LROK White (2018) 62.5%

- Hampden Jamaica Pure Single Rum 7 YO LFCH (2011-2018) 60.5%

- Long Pond “STC♥E” White (2018) 62.5%

2019

- Hampden Jamaica Pure Single Rum 9 YO HGML (2010-2019) 62%

- Long Pond “TECA” 2005 14 YO (2005-2019) 62%

- Monymusk EMB 2010-2019 9 YO (2019) 62%

- Hampden Jamaica Pure Single Rum 9 YO (2010-2019) LROK 63.2% (Salon du Rhum)

- Hampden Jamaica Pure Single Rum 9 YO (2010-2019) HLCF/DOK 61% (The One & Only)

- Hampden Jamaica Pure Single Rum 9 YO (2010-2019) <H> 69.2% (LMDW)

- Hampden Jamaica Pure Single Rum 8 YO (2011-2019) OWH 59.5% (Berlin Bar Convent)

- Hampden Jamaica Pure Single Rum 8 YO (2011-2019) LFCH 61.7% (Whisky Live Singapore 2019)

- Hampden Jamaica Pure Single Rum 7 YO (2012-2019) OWH 62.8% (Whisky Live Paris 2019)

2020

- Privateer New England Pure Single Rum 3 YO (2017-2020) 55.6%

- Privateer New England Pure Single White Rum (2020) 62%

- Mount Gay Barbados Pure Single Rum 9 YO (2011-2020) 52.3%

- Hampden Jamaica Pure Single Rum 10 YO C<>H (2010-2020) 68.5%

- Hampden Jamaica Pure Single Rum 10 YO LROK (2010-2020) 62%

- WP Worthy Park Jamaica Pure Single Rum 11 YO WPL (2009-2020) 58.5%

60.4%

2021

- Mhoba South Africa Pure Single Rum 4 YO (2017-2021) 64.6%

- Takamaka Seychelles Pure Single Rum 3 YO (2018-2021) 60.8%

- Takamaka Seychelles Pure Single Rum Blanc (2020 Unaged) 69%

- Hampden Jamaica Pure Single Rum 5 YO OH (2016 – 2021) 62%

2022

- Momymusk Jamaica Pure Single Rum 7 YO MMW (2015-2022) 59% (1500b)

- Hampden Jamaica Pure Single Rum 3 YO HES (2019-2022) 60.5% (620b)

- Hampden Jamaica Pure Single Rum 5 YO DOK (2017-2022) 60.5% (1800b)

- Longpond Jamaica Pure Single Rum 3 YO STCE (2019-2022) 60% (1200b)

- Amrut Indian Pure Single Rum 7 YO (2015-2022) 62.8% (130b)

2023 (announced, ABV and qty may vary on final release)

- Monymusk Jamaica Single Rum 8 YO EMB ex-Bourbon No.1 (2014-2022) 60% (202b)

- Monymusk Jamaica Single Rum 8 YO EMB ex-Bourbon No.2 (2014-2022) 60% (233b)

- Monymusk Jamaica Single Rum 7 YO MMW ex-Bourbon No.818 (2015-2022) 59% (283b)

- Monymusk Jamaica Single Rum 7 YO MMW ex-Bourbon No.960 (2014-2022) 60% (281b)

The results of that bifurcated ageing regimen and the pot still origin speak for themselves, and personally, wholly on my own account, I can only say the rum is kind of a quiet stunner. The nose startled the hell out of me, I must admit – “…a smoky barbeque with sweetly musky HP sauce?” went the opening words of my handwritten notes — really! It was redolent of the ashes of a dying fire over which a well-marinated shashlik had been grilling and sizzling. Which did not stay long, admittedly: the real rumminess came after – caramel, burnt sugar, bags of fruit. For a while there it even nosed like a pot still white, with slight turpentine, brine, olives and varnishy notes. Red wine, grapes, plums, very ripe apples, bananas, coconut shavings, the smells kept billowing out and all I could think was somebody had somehow managed to stuff the olfactory equivalent of a grocery’s entire fresh produce section in here.

The results of that bifurcated ageing regimen and the pot still origin speak for themselves, and personally, wholly on my own account, I can only say the rum is kind of a quiet stunner. The nose startled the hell out of me, I must admit – “…a smoky barbeque with sweetly musky HP sauce?” went the opening words of my handwritten notes — really! It was redolent of the ashes of a dying fire over which a well-marinated shashlik had been grilling and sizzling. Which did not stay long, admittedly: the real rumminess came after – caramel, burnt sugar, bags of fruit. For a while there it even nosed like a pot still white, with slight turpentine, brine, olives and varnishy notes. Red wine, grapes, plums, very ripe apples, bananas, coconut shavings, the smells kept billowing out and all I could think was somebody had somehow managed to stuff the olfactory equivalent of a grocery’s entire fresh produce section in here.

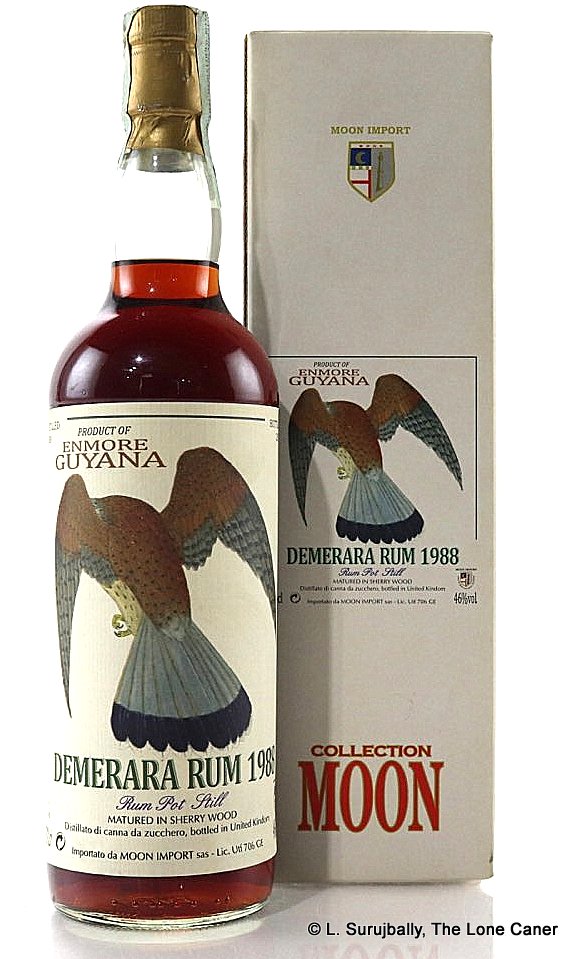

This is not the first Demerara rum that the venerable Italian indie bottler Moon Import has aged in sherry barrels: the superb

This is not the first Demerara rum that the venerable Italian indie bottler Moon Import has aged in sherry barrels: the superb

Opinion

Opinion

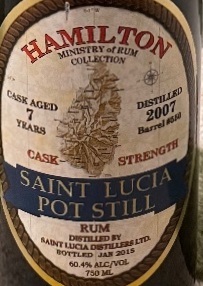

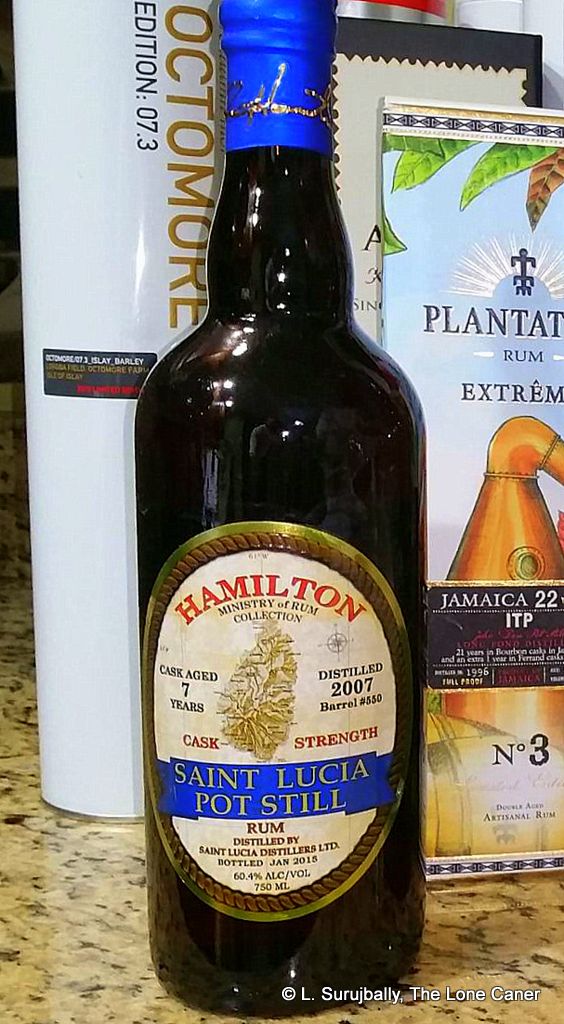

Today we’re looking at the Hamilton 2007 7 year old rum sent to me by my old schoolfriend Cecil Ramotar, which can be considered a companion review to the

Today we’re looking at the Hamilton 2007 7 year old rum sent to me by my old schoolfriend Cecil Ramotar, which can be considered a companion review to the  Clearing away the dishes, it’s a seriously solid rum. If I had to chose, I think the 2004 9 Year Old edges this one out by just a bit, but the difference is more a matter of personal taste than objective quality, as both were very tasty and complex rums that add to SLD’s and Ed Hamilton’s reputations. It’s a shame that the line wasn’t continued and added to — no other St. Lucia rums have been added to the Hamilton Collection since 2015 (at least not according to

Clearing away the dishes, it’s a seriously solid rum. If I had to chose, I think the 2004 9 Year Old edges this one out by just a bit, but the difference is more a matter of personal taste than objective quality, as both were very tasty and complex rums that add to SLD’s and Ed Hamilton’s reputations. It’s a shame that the line wasn’t continued and added to — no other St. Lucia rums have been added to the Hamilton Collection since 2015 (at least not according to  Hampden gets so many kudos these days from its relationship with

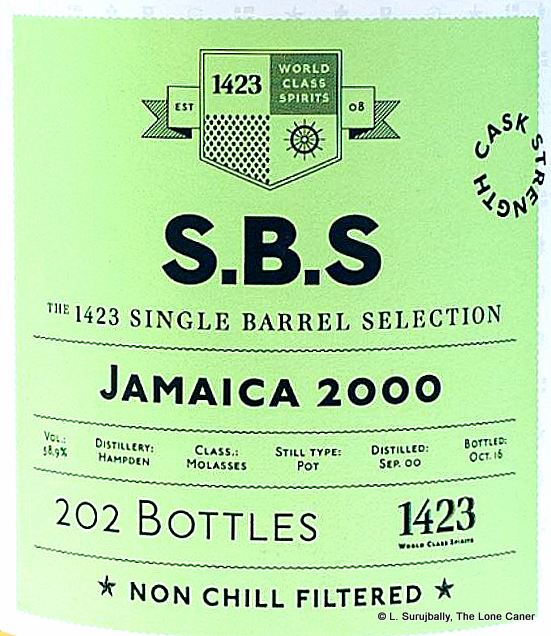

Hampden gets so many kudos these days from its relationship with  The rum displays all the attributes that made the estate’s name after 2016 when they started supplying their rums to others and began bottling their own. It’s a rum that’s astonishingly stuffed with tastes from all over the map, not always in harmony but in a sort of cheerful screaming chaos that shouldn’t work…except that it does. More sensory impressions are expended here than in any rum of recent memory (and I remember

The rum displays all the attributes that made the estate’s name after 2016 when they started supplying their rums to others and began bottling their own. It’s a rum that’s astonishingly stuffed with tastes from all over the map, not always in harmony but in a sort of cheerful screaming chaos that shouldn’t work…except that it does. More sensory impressions are expended here than in any rum of recent memory (and I remember

The nose begins with metallic, ashy notes right away, damp cardboard in a long-abandoned, leaky musty house. Thankfully this peculiar aroma doesn’t hang around, but morphs into a sort of soya-salt veggie soup vibe, which in turn gets muskier and sweeter over time; it releases notes of bananas and molasses and syrup, before gradually lightening and becoming – surprisingly enough – rather crisp. White fruits emerge – unripe pears and guavas, green apples, gooseberries, grapes. What’s really surprising is the way this all transforms over a period of ten minutes or so from one nasal profile to another. It’s not usual, but it is noteworthy.

The nose begins with metallic, ashy notes right away, damp cardboard in a long-abandoned, leaky musty house. Thankfully this peculiar aroma doesn’t hang around, but morphs into a sort of soya-salt veggie soup vibe, which in turn gets muskier and sweeter over time; it releases notes of bananas and molasses and syrup, before gradually lightening and becoming – surprisingly enough – rather crisp. White fruits emerge – unripe pears and guavas, green apples, gooseberries, grapes. What’s really surprising is the way this all transforms over a period of ten minutes or so from one nasal profile to another. It’s not usual, but it is noteworthy.

Bristol, I think, came pretty close with this relatively soft 46% Demerara. The easier strength may have been the right decision because it calmed down what would otherwise have been quite a seriously sharp and even bitter nose. That nose opened with rubber and plasticine and a hot glue gun smoking away on the freshly sanded wooden workbench. There were pencil shavings, a trace of oaky bitterness, caramel, toffee, vanilla and slowly a firm series of crisp fruity notes came to the fore: green apples, raisins, grapes, apples, pears, and then a surprisingly delicate herbal touch of thyme, mint, and basil.

Bristol, I think, came pretty close with this relatively soft 46% Demerara. The easier strength may have been the right decision because it calmed down what would otherwise have been quite a seriously sharp and even bitter nose. That nose opened with rubber and plasticine and a hot glue gun smoking away on the freshly sanded wooden workbench. There were pencil shavings, a trace of oaky bitterness, caramel, toffee, vanilla and slowly a firm series of crisp fruity notes came to the fore: green apples, raisins, grapes, apples, pears, and then a surprisingly delicate herbal touch of thyme, mint, and basil.

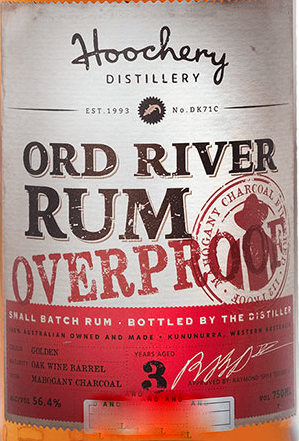

Rums made from scratch by some small new micro-distillery in a country other than the norm are often harbingers of future trends and can bring – alongside the founders’ enthusiasm – some interesting tastes to the table, even different spirits (<<cough>> ‘Murrica!!). But Skotlander, to their credit, didn’t mess around with ten different brandies, gins, vodkas, whiskies and what have you, and then pretended they were always into rum and we are now getting the ultimate pinnacle of their artsy voyage of discovery. Nah. These boys started with rum, bam! from eight o’clock, day one.

Rums made from scratch by some small new micro-distillery in a country other than the norm are often harbingers of future trends and can bring – alongside the founders’ enthusiasm – some interesting tastes to the table, even different spirits (<<cough>> ‘Murrica!!). But Skotlander, to their credit, didn’t mess around with ten different brandies, gins, vodkas, whiskies and what have you, and then pretended they were always into rum and we are now getting the ultimate pinnacle of their artsy voyage of discovery. Nah. These boys started with rum, bam! from eight o’clock, day one.

Luca Gargano has been a fixture on the rum world for so long that people don’t always remember that there was a time when he was a smallish importer, and “just” another newb indie bottler with odd, even controversial, ideas and his rums were considered obscure and too expensive. These days his name is known everywhere rums are drunk (and collected). But paradoxically, it’s gotten to the point where the generation of rum drinkers who have emerged in the last five years don’t remember the seminal nature of his earlier work, just see the currently available ones, and I was asked in mystification just the other week “What Demerara rums?” by a man whose memories begin with Caroni and move into the Hampdens and Habitations. To some extent the HV line allows them to participate in the uniqueness of some of Velier’s early work and ethos… but without paying four figures for the privilege.

Luca Gargano has been a fixture on the rum world for so long that people don’t always remember that there was a time when he was a smallish importer, and “just” another newb indie bottler with odd, even controversial, ideas and his rums were considered obscure and too expensive. These days his name is known everywhere rums are drunk (and collected). But paradoxically, it’s gotten to the point where the generation of rum drinkers who have emerged in the last five years don’t remember the seminal nature of his earlier work, just see the currently available ones, and I was asked in mystification just the other week “What Demerara rums?” by a man whose memories begin with Caroni and move into the Hampdens and Habitations. To some extent the HV line allows them to participate in the uniqueness of some of Velier’s early work and ethos… but without paying four figures for the privilege. The HV series, then, are perhaps more aimed at that midrange bunch of relatively knowledgeable drinkers, influencers and anoraks, rather than for some high priced connoisseur’s market (where money but not knowledge is more often the real coin of the realm) or the deep-diving über-dorks (where exacting command of micro-detailed minutiae is). They are, in that sense, a useful bridge between more commonly appreciated rums, and those that require a bit more experience, perhaps, to fully appreciate — and can therefore be had and enjoyed and argued over by both long-time aficionados and new-to-the-club rumgeek wannabes.

The HV series, then, are perhaps more aimed at that midrange bunch of relatively knowledgeable drinkers, influencers and anoraks, rather than for some high priced connoisseur’s market (where money but not knowledge is more often the real coin of the realm) or the deep-diving über-dorks (where exacting command of micro-detailed minutiae is). They are, in that sense, a useful bridge between more commonly appreciated rums, and those that require a bit more experience, perhaps, to fully appreciate — and can therefore be had and enjoyed and argued over by both long-time aficionados and new-to-the-club rumgeek wannabes.

Certainly the 2003 10 YO does its next-best relative the

Certainly the 2003 10 YO does its next-best relative the

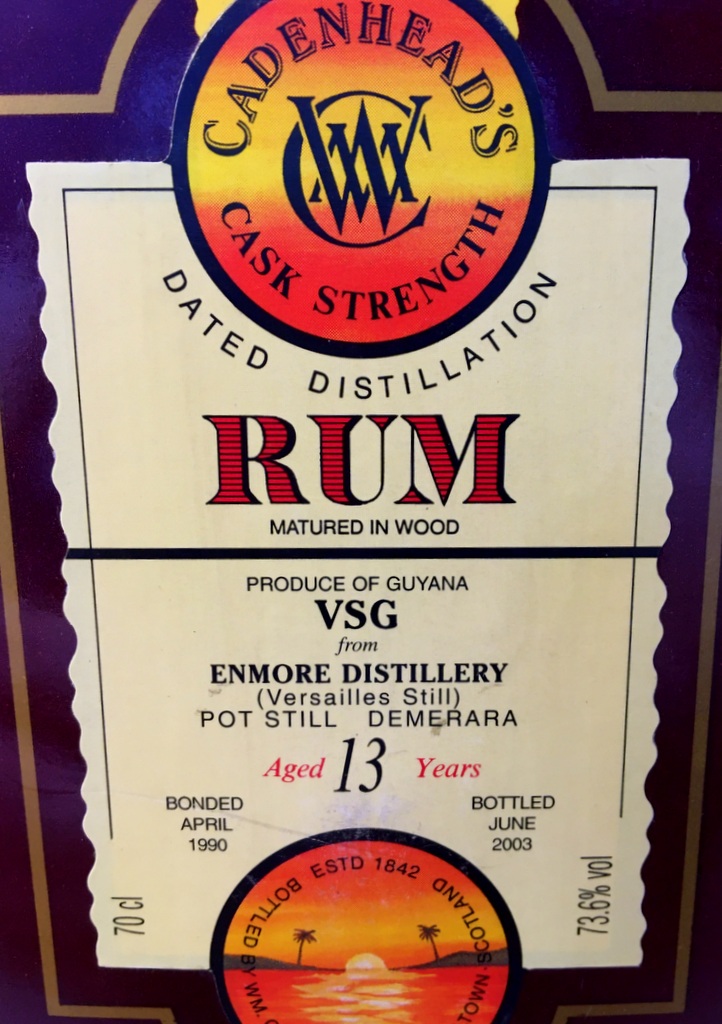

My own preference has always been for the stern elegance of the Port Mourant, and the Enmore coffey still produces rums that are complex, graceful and sophisticated when done right. But the Versailles still is something of an ugly stepchild – you’ll go far and look long to find an unqualified positive review of any rum it spits out. I’ve always felt that it takes rare skill to bring the rough and raw VSG pot still profile to its full potential…none of the familiar indies has had more than occasional success with it, and even Velier never really bothered to produce much Versailles rum at the height of

My own preference has always been for the stern elegance of the Port Mourant, and the Enmore coffey still produces rums that are complex, graceful and sophisticated when done right. But the Versailles still is something of an ugly stepchild – you’ll go far and look long to find an unqualified positive review of any rum it spits out. I’ve always felt that it takes rare skill to bring the rough and raw VSG pot still profile to its full potential…none of the familiar indies has had more than occasional success with it, and even Velier never really bothered to produce much Versailles rum at the height of  There has been occasional confusion among the stills in the past: e.g. the

There has been occasional confusion among the stills in the past: e.g. the

So let’s spare some time to look at this rather unique white rum released by Habitation Velier, one whose brown bottle is bolted to a near-dyslexia-inducing name only a rum geek or still-maker could possibly love. And let me tell you, unaged or not, it really is a monster truck of tastes and flavours and issued at precisely the right strength for what it attempts to do.

So let’s spare some time to look at this rather unique white rum released by Habitation Velier, one whose brown bottle is bolted to a near-dyslexia-inducing name only a rum geek or still-maker could possibly love. And let me tell you, unaged or not, it really is a monster truck of tastes and flavours and issued at precisely the right strength for what it attempts to do. Evaluating a rum like this requires some thinking, because there are both familiar and odd elements to the entire experience. It reminds me of

Evaluating a rum like this requires some thinking, because there are both familiar and odd elements to the entire experience. It reminds me of

As for the finish, well, in rum terms it was longer than the current Guyanese election and seemed to feel that it was required that it run through the entire tasting experience a second time, as well as adding some light touches of acetone and rubber, citrus, brine, plus everything else we had already experienced the palate. I sighed when it was over…and poured myself another shot.

As for the finish, well, in rum terms it was longer than the current Guyanese election and seemed to feel that it was required that it run through the entire tasting experience a second time, as well as adding some light touches of acetone and rubber, citrus, brine, plus everything else we had already experienced the palate. I sighed when it was over…and poured myself another shot.

Let’s see if we can’t redress that somewhat. This is a Jamaican rum from Longpond, double pot still made, 62% ABV, 14 years old, and released as one of the pot still rums the Habitation Velier line is there to showcase. I will take it as a given it’s been completely tropically aged. Note of course, the ester figure of 1289.5 gr/hlpa, which is very close to the maximum (1600) allowed by Jamaican law. What we could expect from such a high number, then, is a rum sporting taste-chops of uncommon intensity and flavour, as rounded off by nearly a decade and a half of ageing – now, those statistics made the TECA 2018 detonate in your face and it’s arguable whether that’s a success, but here? … it worked. Swimmingly.

Let’s see if we can’t redress that somewhat. This is a Jamaican rum from Longpond, double pot still made, 62% ABV, 14 years old, and released as one of the pot still rums the Habitation Velier line is there to showcase. I will take it as a given it’s been completely tropically aged. Note of course, the ester figure of 1289.5 gr/hlpa, which is very close to the maximum (1600) allowed by Jamaican law. What we could expect from such a high number, then, is a rum sporting taste-chops of uncommon intensity and flavour, as rounded off by nearly a decade and a half of ageing – now, those statistics made the TECA 2018 detonate in your face and it’s arguable whether that’s a success, but here? … it worked. Swimmingly. So – good or bad? Let’s see if we can sum this up. In short, I believe the 2005 TECA was a furious and outstanding rum on nearly every level. But that comes with caveats. “Fasten your seatbelt” remarked Serge Valentin

So – good or bad? Let’s see if we can sum this up. In short, I believe the 2005 TECA was a furious and outstanding rum on nearly every level. But that comes with caveats. “Fasten your seatbelt” remarked Serge Valentin  Anyone from my generation who grew up in the West Indies knows of the scalpel-sharp satirical play “Smile Orange,” written by that great Jamaican playwright, Trevor Rhone, and made into an equally funny film of the same name in 1976. It is quite literally one of the most hilarious theatre experiences of my life, though perhaps an islander might take more away from it than an expat. Why do I mention this irrelevancy? Because I was watching the YouTube video of the film that day in Berlin when I was sampling the Worthy Park series R 11.3, and though the film has not aged as well as the play, the conjoined experience brought to mind all the belly-jiggling reasons I so loved it, and Worthy Park’s rums.

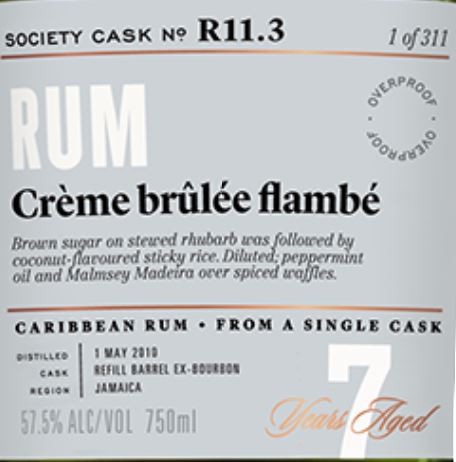

Anyone from my generation who grew up in the West Indies knows of the scalpel-sharp satirical play “Smile Orange,” written by that great Jamaican playwright, Trevor Rhone, and made into an equally funny film of the same name in 1976. It is quite literally one of the most hilarious theatre experiences of my life, though perhaps an islander might take more away from it than an expat. Why do I mention this irrelevancy? Because I was watching the YouTube video of the film that day in Berlin when I was sampling the Worthy Park series R 11.3, and though the film has not aged as well as the play, the conjoined experience brought to mind all the belly-jiggling reasons I so loved it, and Worthy Park’s rums. The distillation run from 2010 must have been a good year for Worthy Park, because the SMWS bought no fewer than seven separate casks from then to flesh out its R11 series of rums (R11.1 through R11.6 were distilled May 1st of that year, with R11.7 in September, and all were released in 2017). After that, I guess the Society felt its job was done for a while and pulled in its horns, releasing nothing in 2018 from WP, and only one more — R11.8 — the following year; they called it “Big and Bountiful” though it’s unclear whether this refers to Jamaican feminine pulchritude or Jamaican rums.

The distillation run from 2010 must have been a good year for Worthy Park, because the SMWS bought no fewer than seven separate casks from then to flesh out its R11 series of rums (R11.1 through R11.6 were distilled May 1st of that year, with R11.7 in September, and all were released in 2017). After that, I guess the Society felt its job was done for a while and pulled in its horns, releasing nothing in 2018 from WP, and only one more — R11.8 — the following year; they called it “Big and Bountiful” though it’s unclear whether this refers to Jamaican feminine pulchritude or Jamaican rums.