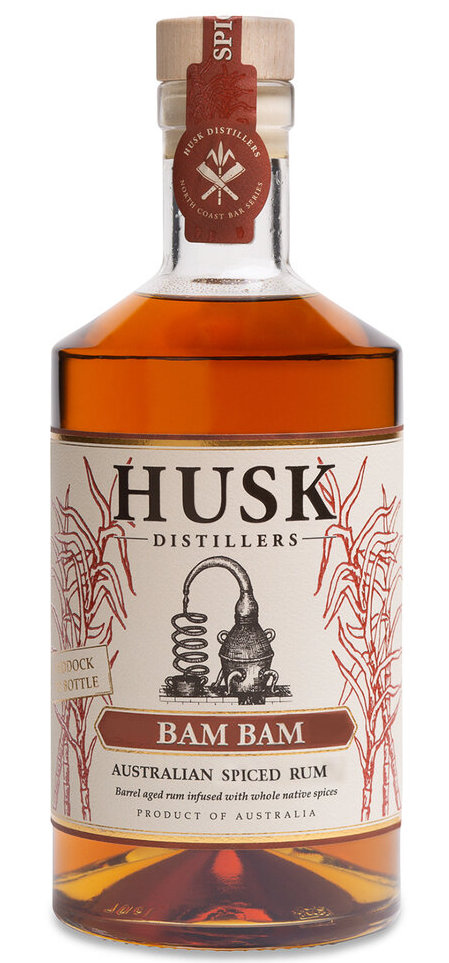

Of the New Australian distilleries that have emerged in the last ten years, Husk may be one of the older ones. Its inspiration dates back to 2009 when the founder, Paul Messenger, was vacationing in the Caribbean; while on Martinique, he was blown away by agricole rhums and spent the next few years establishing a small distillery in northern New South Wales (about 120km SE of Brisbane) which was named “Husk” when it opened in 2012. Its uniqueness was and remains that it uses its own estate-grown sugar cane to make rum from juice, not molasses, and is a field-to-bottle integrated producer unbeholden to any external processing outfit for supplies of cane, syrup, juice or molasses. Initially they used a pot still but as their popularity grew it was replaced with a hybrid pot-column still (the old still remains at the entrance to the distillery).

As is standard practice in Australia, while rums wait two years to age before being called “rum”, other spirits are made to fill the gap and provide cash flow – in this case there was a gin called “Ink”, and a set of “Cane Spirits” products which were initially a pair of unaged agricole-style rums at two strengths, plus a botanical and a spiced. These continue to be made and pay the bills but there were and are others: in 2015 a “virgin cane rum,” came out, limited to 300 bottles; in 2016 a 3YO aged rum was released (the “1866 Tumbulgum”); in 2018 a 5 YO (“Triple Oak”) – all were cane juice rums and these days both are hard to find any longer. In 2021 they issued “The Lost Blend” virgin cane aged rum with “subtropical ageing” (coming soon to the review site near you) and in the spiced category, they have periodic releases of the spiced rum we are looking at today, which they call “Bam Bam” (for obscure reasons of their own that may or may not be related to a children’s cartoon, but then, they do say they make better rums than jokes).

The rum clocks in at standard strength (40%) and is, as far as I am aware, a pot still cane juice product, aged for 3 years in oak (not sure what kind or from where it came) and added spices of wattleseed, ginger, orange, cinnamon, golden berry, vanilla and sea salt. I should point out here that all of this was unknown to me when I tasted the sample — the labels on the advent calendar didn’t mention it at all.

So…the nose. Initially redolent of ripe, fleshy fruits — apricots, peaches, bananas, overripe mangoes and dark cherries — into which are mixed crushed walnuts, pistachios and sweet Danish cookies plus a drop or two of vanilla. It’s soft and decidedly sweet with a creamy aroma resembling a lemon meringue pie topped with whipped cream, then dusted with cinnamon…and a twist of ginger off a sushi plate.

So…the nose. Initially redolent of ripe, fleshy fruits — apricots, peaches, bananas, overripe mangoes and dark cherries — into which are mixed crushed walnuts, pistachios and sweet Danish cookies plus a drop or two of vanilla. It’s soft and decidedly sweet with a creamy aroma resembling a lemon meringue pie topped with whipped cream, then dusted with cinnamon…and a twist of ginger off a sushi plate.

The taste maintains that gentle sweetness which so recalled a well done sweet pastry. There was cream cheese, butter, cookies and white chocolate, plus some breakfast-cereal notes and mild chocolate. A few fruits drift in and out the of the profile from time to time, a touch of lime, an apricot, raisins, a ripe apple or two. And with some patience, baking spices like cinnamon and nutmeg are noticeable, but it’s all rather faint and very light, leading to a short and quickly concluded finish with orange peel, vanilla, brown sugar, and that tantalising hint of cake batter that evokes a strong nostalgic memories of fighting with my brother for the privilege of finger-licking the bowl of cake mix after Ma Caner was done with it.

Overall, it’s a peculiar rum because there’s little about it that shouts “rum” at all (on their marketing material they claim the opposite, so your own mileage may vary). My own take is that it’s alcohol, it has some interesting non-rum flavours, it will get you drunk if you take enough of it and it has lovely creamy and cereal-y notes that I like. But overall it’s too thin (a function of the 40%) too easy, the spices kind of overwhelm after a while and it seems like a light rum with little greater purpose in life than to jazz up a mixed drink someplace. That’s not enough to sink it, or refuse it when offered, just not enough for me to run out and get one immediately.

(#893)(80/100) ⭐⭐⭐

Other Notes

- As with all the Australian rums reviewed as part of the 2021 Aussie Advent Calendar, a very special shout out and a chuck of the chullo to Mr. And Mrs. Rum, who sent me a complete set free of charge. Thanks, as always, to you both.

- Husk refers to its rums as “agricoles” (see promo poster above) but incorrectly in my view, as this is a term that by convention, common usage and EU regulation refers to cane juice rhums made in specific countries (Madeira, Reunion, Guadeloupe and Martinique). A re-labelling or rebranding might have to be done at some point if the EU market is to be accessed. Personally, I think they should do so anyway. Nothing wrong with “agricole-style” or “cane juice rhum” or some other such variation, and that keeps things neat and tidy (my personal opinion only).

- Long time readers will know I am not a great fan of spiced or infused rums and this preference (or lack thereof) of mine must be factored into the review. The tastes are as they are, but my interpretation of how they work will be different from that of anther person who likes such products more than I do. Mrs. Caner, by the way, really enjoyed it.