The Scarlet Ibis rum is not as well known as it was a decade ago, but that it continues to be in production at all is a testament to its overall utility and perceived worth in the bar scene. That said, it remains something of an unknown quantity to the mass of rum drinkers, sharing negative mindspace with, oh, say, Sea Wynde or Edwin Charley, which had their moment in the Age of Blends but have now fallen from common knowledge. In a few more years they’ll join all those other rums that recede into vague memory if a greater push isn’t made to elevate customer awareness and sales.

Where does one start? First of all, it is a rum made to order, commissioned by the New York bar Death & Co. The exact year it arrived is unknown, but since D&Co was established in January 2007 (it opened on New Year’s Eve) and since the first note I can find about the rum itself related to a 2010 MoR festival (so the rum had to have been available before that), then it’s been around since 2008-2009 or so, with short observations and reviews popping up intermittently at best ever since. 1. Eric Seed, the NY importing rep for the European distributor Haus Alpenz (which also helped source the Smith & Cross, you’ll remember) seems to have been instrumental in being point man for its creation and subsequently bringing into the US.

Production is intermittent at best, paralleling the equally inconsistent geographical availability. Facebook is littered with the detritus of occasional comments like “Where can I find it?” “Is it still being made?” “Like the new one?” or “When did it become available again?” Most who have tried it and have commented on the rum think it’s very nice, and the extra proof is appreciated. In earlier posts some suggested that the original blend had some Caroni, but Alpenz denied that, and also noted that there was an error in the press materials and it was and always has been a completely column-still product, a blend of 3-5 year old stocks, bottled at 49%.

So, a youngish rum blend, made to order. That makes it an interesting rum, quite different from most others from the twin island republic which are either overpriced Caronis (on the secondary market) or Angostura’s own decently unexceptional blends. It’s light and sharp (what some refer to as “peppery”) on the initial nose, kind of sweet and cheeky, like the playful towel-snap your older brother used to like flicking in your direction. It had notes of ripe red cherries, soft mangoes and a touch of lemon juice, honey, butterscotch and brine, which went well with some aromatic tobacco and a very faint hint of a rubber tyre.

Even at 49%, I’m afraid that it didn’t live up to the suggested quality the nose implied. Initial tastes were honey, unsweetened molasses, Guinness stout, olives and pimentos (!!), with some slowly developing fruits – dark grapes, raisins, gooseberries – plus red wine, chocolate and coffee grounds. The finish was short, not very emphatic, quite warm: mostly tobacco, light fruits, olives, toffee and a last hint of citrus. It doesn’t last long, and just sort of sidles out of the way without any fuss or bother.

Overall, it’s good, but also something of a let down. Even at 49% it seems too mild for what it seems it could present (and this from a relatively young series of blend components, so the potential is definitely there). There’s more in the trousers there someplace, the rum has a lot more it feels like it could say, but it is hampered by a lack of focus: leaving aside the proof point, it’s as if the makers weren’t sure they wanted to go in the direction of something darker (like a Caroni), or a lighter blend similar to (but different from) Angostura’s own portfolio. In a better designed rum it could have navigated a surer path between those two profiles, but as it is, the execution only shows us what could have been, without coming through with something more memorable.

(#865)(78/100)

Other Notes

- As always, hat tip and appreciation to my old QC Rum Chum, Cecil, who passed the sample on to me.

- The first remarks on the rum came from Sir Scrotimus in 2011. There’s a positive bartender’s blog review in 2012, the Fat Rum Pirate picked up a bottle in the UK and wrote quite positively about it in 2015, and Rum Revelations did an indifferent pass-through in 2020. Redditors have done reviews about it here, here and here. Overall, the consensus is a good one. The rum definitely has more potential than its makers seem to grasp.

- The Scarlet Ibis is the national bird of Trinidad & Tobago and is featured on the coat of arms

- The new edition of the rum which came out around 2019-2020 has a pair of ibises on the label. These are far more prominent than the grayed out bird on older editions such as the one I am reviewing here.

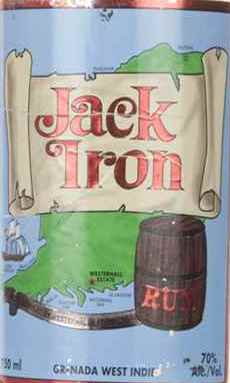

The Jack Iron rum from Westerhall is a booming overproof issued both in a slightly aged and a white version, and both are a whopping 70% ABV. While you can get it abroad — this bottle was tried in Italy, for example — my take is that it’s primarily a rum for local consumption (though which island can lay claim to it is a matter of idle conjecture), issued to paralyze brave-but-foolhardy tourists who want to show off their Chewbacca chests by drinking it neat, or to comfort the locals who don’t have time to waste getting hammered and just want to do it quick time. Add to that the West Indian slang for manly parts occasionally being iron and you can sense a sort of cheerful and salty islander sense of humour at work (see “other notes” below for an alternative backstory).

The Jack Iron rum from Westerhall is a booming overproof issued both in a slightly aged and a white version, and both are a whopping 70% ABV. While you can get it abroad — this bottle was tried in Italy, for example — my take is that it’s primarily a rum for local consumption (though which island can lay claim to it is a matter of idle conjecture), issued to paralyze brave-but-foolhardy tourists who want to show off their Chewbacca chests by drinking it neat, or to comfort the locals who don’t have time to waste getting hammered and just want to do it quick time. Add to that the West Indian slang for manly parts occasionally being iron and you can sense a sort of cheerful and salty islander sense of humour at work (see “other notes” below for an alternative backstory).

First posted 19th January 2010 on Liquorature.

First posted 19th January 2010 on Liquorature.