Rumaniacs Review #116 | 0732

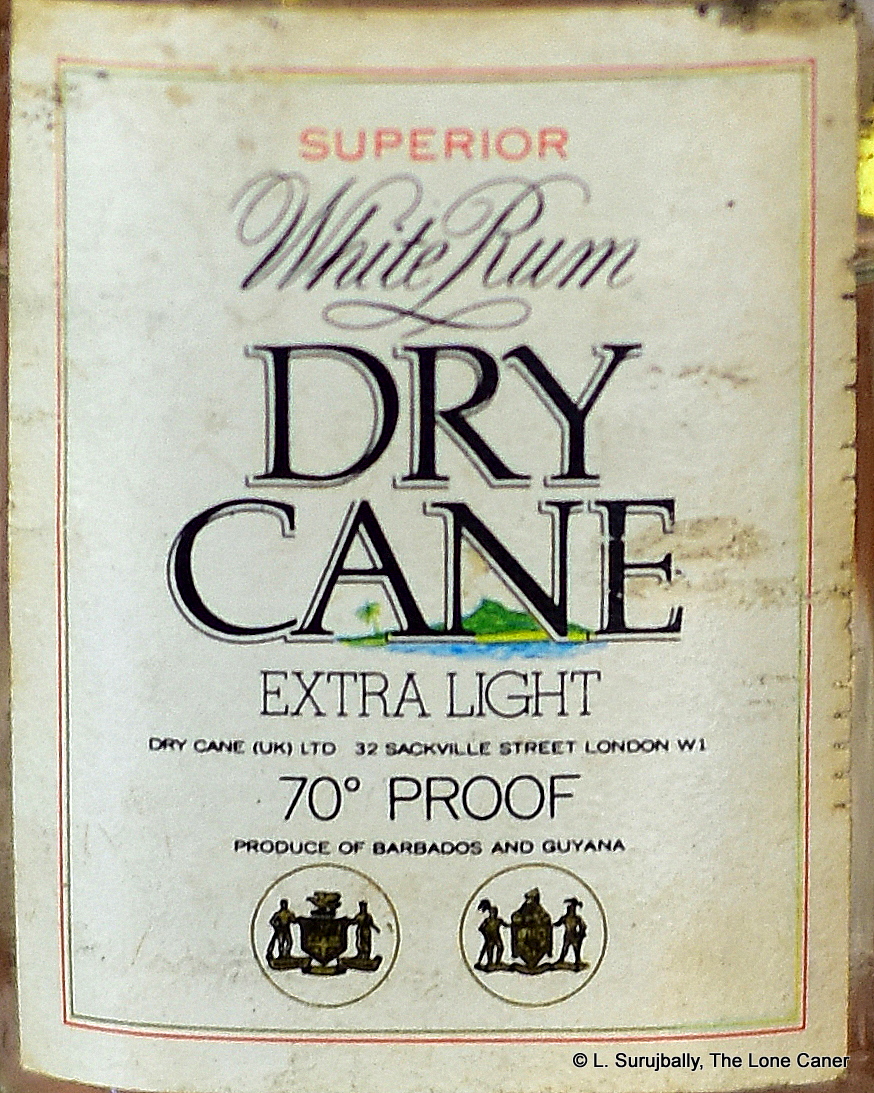

Dry Cane UK had several light white rums in its portfolio – some were 37.5% ABV, some were Barbados only, some were 40%, some Barbados and Guyanese blends. All were issued in the 1970s and maybe even as late as the 1980s, after which the trail goes cold and the rums dry up, so to speak. This bottle however, based on photos on auction sites, comes from the 1970s in the pre-metric era when the strength of 40% ABV was still referred to as 70º in the UK. It probably catered to the tourist, minibar, and hotel trade, as “inoffensive” and “unaggressive” seem to be the perfect words to describe it, and II don’t think it has ever made a splash of any kind.

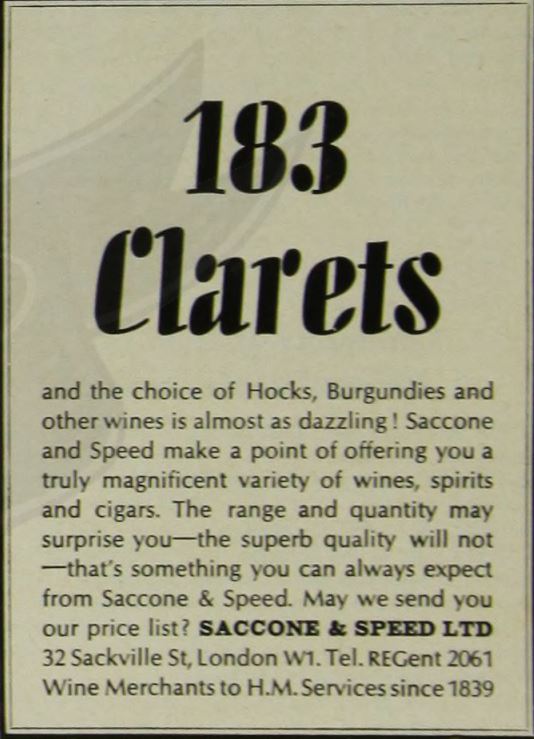

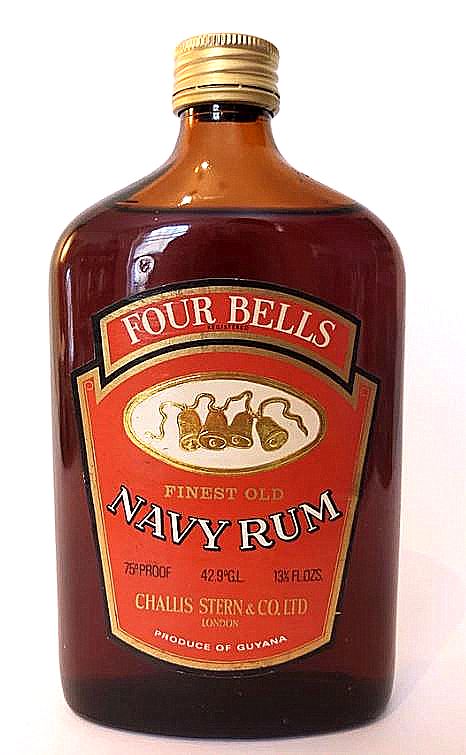

As to who exactly Dry Cane (UK) Ltd were, let me save you the trouble of searching – they can’t be found. The key to their existence is the address of 32 Sackville Street noted on the label, which details a house just off Piccadilly dating back to the 1730s. Nowadays it’s an office, but in the 1970s and before, a wine, spirits and cigar merchant called Saccone & Speed (established in 1839) had premises there, and had been since 1932 when they bought Hankey Bannister, a whisky maker, in that year. HB had been in business since 1757, moved to Sackville Street in 1915 and S&S just took over the premises. Anyway, Courage Breweries took over S&S in 1963 and handed over the spirits section of the UK trade to another subsidiary, Charles Kinloch – who were responsible for that excellent tipple, the Navy Neaters 95.5º we have looked at before (and really enjoyed).

My inference is therefore that Dry Cane was a financing vehicle or shell company or wholly owned subsidiary set up for a short time to limit the exposure of the parent company (or Kinloch), as it dabbled in being an independent bottler — and just as quickly retreated, for no further products were ever made so far as I can tell. But since S&S also acquired a Gibraltar drinks franchise in 1968 and gained the concession to operate a duty free shop at Gibraltar airport in 1973, I suspect this was the rationale behind creating the rums in the first place, through the reason for its cessation is unknown. Certainly by the time S&S moved out of Sackville Street in the 1980s and to Gibraltar (where they remain to this day as part of a large conglomerate), the rum was no longer on sale.

My inference is therefore that Dry Cane was a financing vehicle or shell company or wholly owned subsidiary set up for a short time to limit the exposure of the parent company (or Kinloch), as it dabbled in being an independent bottler — and just as quickly retreated, for no further products were ever made so far as I can tell. But since S&S also acquired a Gibraltar drinks franchise in 1968 and gained the concession to operate a duty free shop at Gibraltar airport in 1973, I suspect this was the rationale behind creating the rums in the first place, through the reason for its cessation is unknown. Certainly by the time S&S moved out of Sackville Street in the 1980s and to Gibraltar (where they remain to this day as part of a large conglomerate), the rum was no longer on sale.

Colour – White

Strength – 40% ABV

Nose – Light and sweet; toblerone, almonds, a touch of pears. Its watery and weak, that’s the problem with it, but interestingly, aside from all the stuff we’re expecting (and which we get) I can smell lipstick and nail polish, which I’m sure you’ll admit is unusual. It’s not like we find this rum in salons of any kind.

Palate – Light and inoffensive, completely bland. Pears, sugar water, some mint. You can taste a smidgen of alcohol behind all that, it’s just that there’s nothing really serious backing it up or going on.

Palate – Light and inoffensive, completely bland. Pears, sugar water, some mint. You can taste a smidgen of alcohol behind all that, it’s just that there’s nothing really serious backing it up or going on.

Finish – Short, dreary, light, simple. Some sugar again and something of a vanilla cake, but even that’s reaching a bit.

Thoughts – Well, one should not be surprised. It does tell you it’s “extra light”, right there on the label; and at this time in rum history, light blends were all the rage. It is not, I should note, possible to separate out the Barbadian from the Guyanese portions. I think the simple and uncomplex profile lends credence to my theory that it was something for the hospitality industry (duty free shops, hotel minibars, inflight or onboard boozing) and served best as a light mixing staple in bars that didn’t care much for top notch hooch, or didn’t know of any.

(74/100)

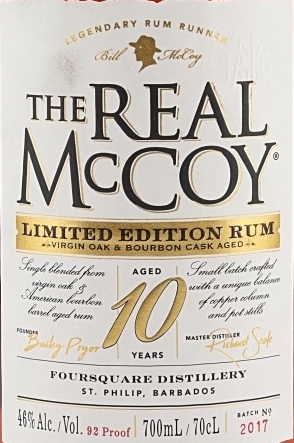

On the palate, the slightly higher strength worked, up to a point. It’s a lot better than 40%, and allowed a certain heft and firmness to brush across the tongue. This then enhanced a melded mishmash of fruits – watermelon, bananas, papaya – plus cocoa butter, coconut shavings in a Bounty chocolate bar, honey and a pinch of salt and vanilla, all of which got shouldered aside by the tannic woodiness. I suspect the virgin oak is responsible for that surfeit, and it made the rum sharper and crisper than those McCoy and Foursquare rums we’re used to, not entirely to the rum’s advantage. The finish summed of most of this – it was dry, rather rough, sharp, and pretty much gave caramel, vanilla, light fruits, and some last tannins which were by now starting to fade. (Subsequent sips and a re-checks over the next few days don’t appreciably change these notes).

On the palate, the slightly higher strength worked, up to a point. It’s a lot better than 40%, and allowed a certain heft and firmness to brush across the tongue. This then enhanced a melded mishmash of fruits – watermelon, bananas, papaya – plus cocoa butter, coconut shavings in a Bounty chocolate bar, honey and a pinch of salt and vanilla, all of which got shouldered aside by the tannic woodiness. I suspect the virgin oak is responsible for that surfeit, and it made the rum sharper and crisper than those McCoy and Foursquare rums we’re used to, not entirely to the rum’s advantage. The finish summed of most of this – it was dry, rather rough, sharp, and pretty much gave caramel, vanilla, light fruits, and some last tannins which were by now starting to fade. (Subsequent sips and a re-checks over the next few days don’t appreciably change these notes).

Colour – Very dark brown

Colour – Very dark brown

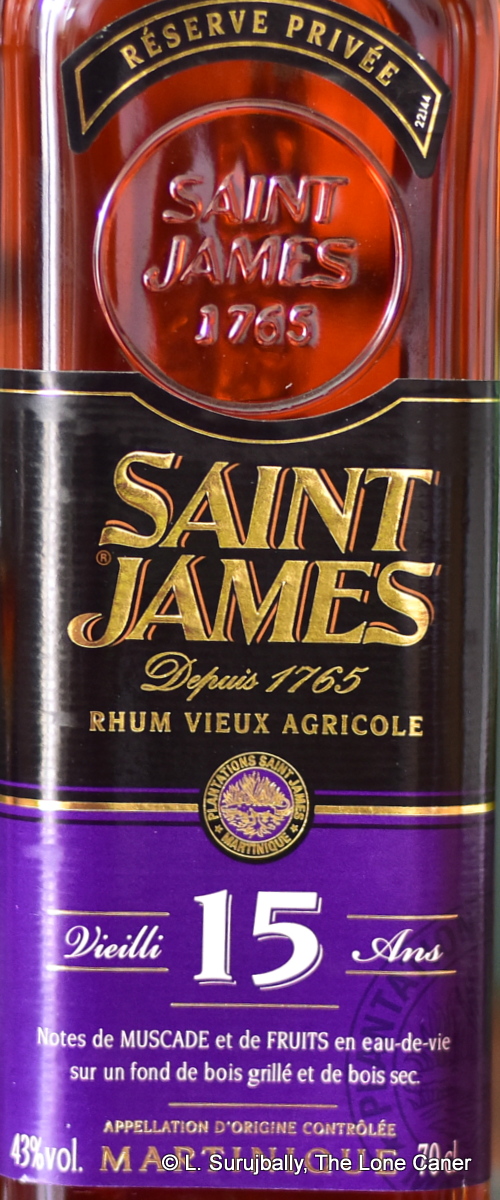

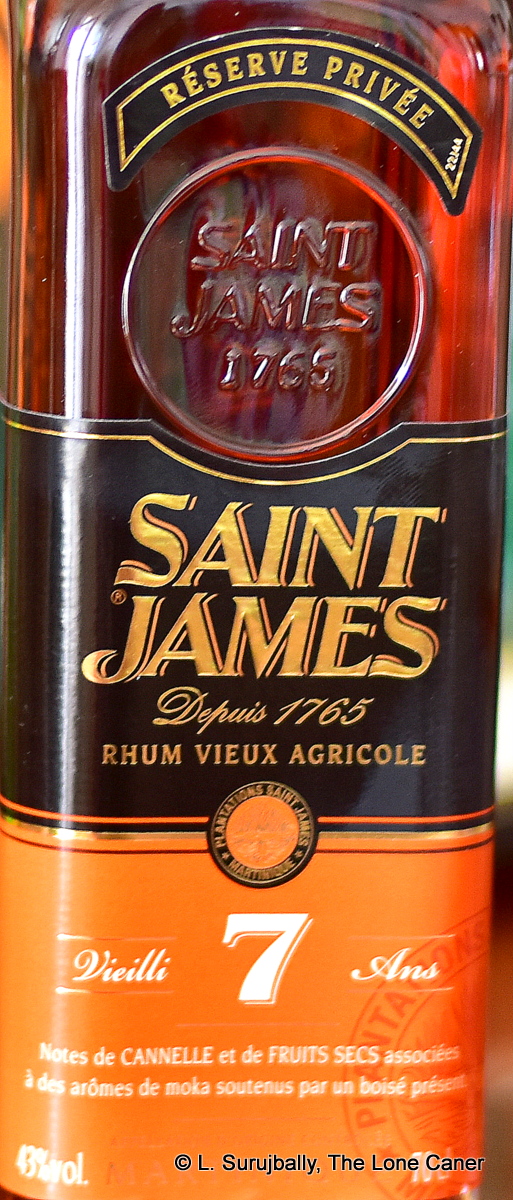

Because that 15 year old rhum is, to my mind, something of an underground, mass-produced steal. It has the most complex nose of the “regular” lineup, and also, paradoxically, the lightest overall profile — and also the one where the grassiness and herbals and the cane sap of a true agricole comes through the most clearly. It has the requisite crisp citrus and wet grass smells, sugar came sap and herbs, and combines that with honey, the delicacy of white roses, vanilla, light yellow fruits, green grapes and apples. You could just close your eyes and not need ruby slippers to be transported to the island, smelling this thing. It’s sweet, mellow and golden, a pleasure to hold in your glass and savour

Because that 15 year old rhum is, to my mind, something of an underground, mass-produced steal. It has the most complex nose of the “regular” lineup, and also, paradoxically, the lightest overall profile — and also the one where the grassiness and herbals and the cane sap of a true agricole comes through the most clearly. It has the requisite crisp citrus and wet grass smells, sugar came sap and herbs, and combines that with honey, the delicacy of white roses, vanilla, light yellow fruits, green grapes and apples. You could just close your eyes and not need ruby slippers to be transported to the island, smelling this thing. It’s sweet, mellow and golden, a pleasure to hold in your glass and savour

1423, the Danish indie, has taken this concept a step further with their 2019 release of a Brazil / Barbados carnival — it comprised of 8- and 3-year old Foursquare rums (exact proportions unknown, both column still) to which was added an unaged cachaca from Pirassununga (they make the very popular “51” just outside Sao Paolo), and the whole thing left to age for two years in Moscatel wine casks for two years, before being squeezed out into 323 bottles at 52% ABV.

1423, the Danish indie, has taken this concept a step further with their 2019 release of a Brazil / Barbados carnival — it comprised of 8- and 3-year old Foursquare rums (exact proportions unknown, both column still) to which was added an unaged cachaca from Pirassununga (they make the very popular “51” just outside Sao Paolo), and the whole thing left to age for two years in Moscatel wine casks for two years, before being squeezed out into 323 bottles at 52% ABV.

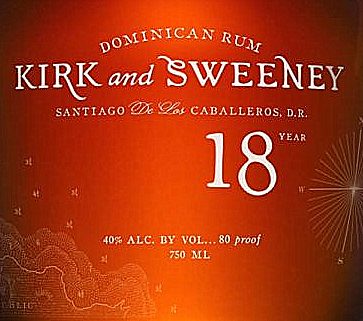

This is not to say that there isn’t some interesting stuff to be found. Take the nose, for example. It smells of salted caramel, vanilla ice cream, brown sugar, a bit of molasses, and is warm, quite light, with maybe a dash of mint and basil thrown in. But taken together, what it has is the smell of a milk shake, and there doesn’t seem to be much in the way of startling originality – not exactly what 18 years of ageing would give you, pleasant as it is. It’s soft and easy, that’s all. No thinking required.

This is not to say that there isn’t some interesting stuff to be found. Take the nose, for example. It smells of salted caramel, vanilla ice cream, brown sugar, a bit of molasses, and is warm, quite light, with maybe a dash of mint and basil thrown in. But taken together, what it has is the smell of a milk shake, and there doesn’t seem to be much in the way of startling originality – not exactly what 18 years of ageing would give you, pleasant as it is. It’s soft and easy, that’s all. No thinking required.

Here’s what we know – made from rendered sugar cane juice (“honey”), fermented for 72 hours using wild yeast, column distilled, then aged in all kinds of barrels – American oak (ex-bourbon), cognac, Pedro Ximenez and also Marcuya “fruit of passion” wood from Paraguay. Once that’s done, the resultant rons are blended to form the final product. The age is currently unknown — I’ll update this paragraph if I get feedback from their marketing folks — but I’ll hazard a guess it’s medium…about 3-6 years. Little of this, by the way, is noted on the label, which only says it is a Paraguayan rum, commemorates the 1869 battle, is aged in oak vats and 40%. Wonderful. Clearly the word “disclosure” gets more lip service than real purchase over there.

Here’s what we know – made from rendered sugar cane juice (“honey”), fermented for 72 hours using wild yeast, column distilled, then aged in all kinds of barrels – American oak (ex-bourbon), cognac, Pedro Ximenez and also Marcuya “fruit of passion” wood from Paraguay. Once that’s done, the resultant rons are blended to form the final product. The age is currently unknown — I’ll update this paragraph if I get feedback from their marketing folks — but I’ll hazard a guess it’s medium…about 3-6 years. Little of this, by the way, is noted on the label, which only says it is a Paraguayan rum, commemorates the 1869 battle, is aged in oak vats and 40%. Wonderful. Clearly the word “disclosure” gets more lip service than real purchase over there.

Ah but when sipped, all that changes, and the clodhoppers go away and it dons a pair of ballet slippers. It’s stunningly fragrant, not quite delicate – that ballerina does have an extra pound or two – very firm and robust in flavour profile. Just on the first sip you can taste flowers, pears, papaya, honey, vanilla, raisins, grapes, all pulled together with a delectable light and salty note. There are nice citrus hints, a tease from the oak, ginger and cinnamon, and overall, it sips as nicely as it mixes. The finish is well handled, though content to play it safe – things are beginning to quieten down here, and it fades quietly without stomping on you – and certainly nothing new or original comes into being; the rhum is content to follow where the nose and palate led – fruits, pineapple, spices, ginger, vanilla – without breaking any new ground.

Ah but when sipped, all that changes, and the clodhoppers go away and it dons a pair of ballet slippers. It’s stunningly fragrant, not quite delicate – that ballerina does have an extra pound or two – very firm and robust in flavour profile. Just on the first sip you can taste flowers, pears, papaya, honey, vanilla, raisins, grapes, all pulled together with a delectable light and salty note. There are nice citrus hints, a tease from the oak, ginger and cinnamon, and overall, it sips as nicely as it mixes. The finish is well handled, though content to play it safe – things are beginning to quieten down here, and it fades quietly without stomping on you – and certainly nothing new or original comes into being; the rhum is content to follow where the nose and palate led – fruits, pineapple, spices, ginger, vanilla – without breaking any new ground. The strangely named Doctor Bird rum is another company’s response to

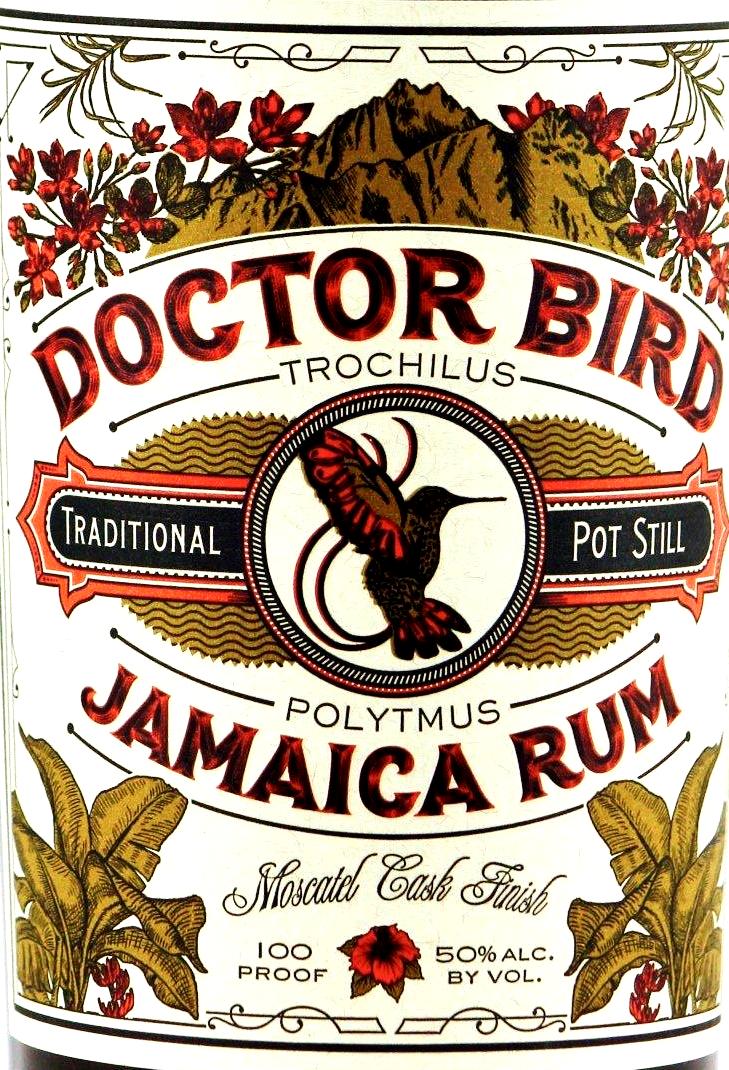

The strangely named Doctor Bird rum is another company’s response to

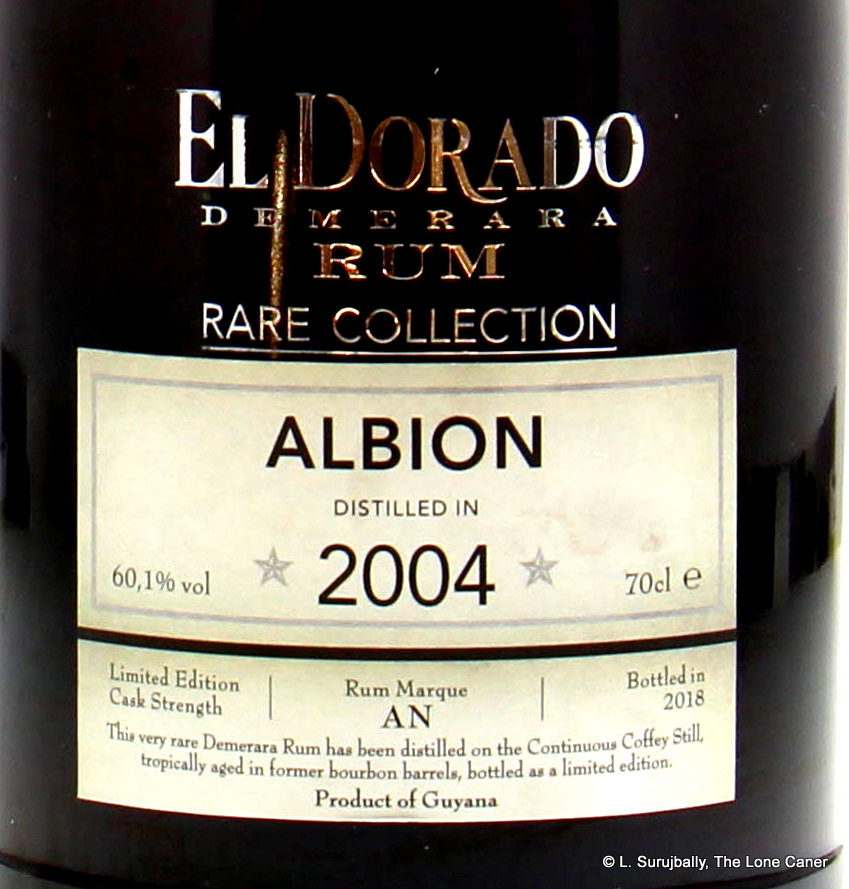

Palate – Even if they didn’t say so on the label, I’d say this is almost completely Guyanese just because of the way all the standard wooden-still tastes are so forcefully put on show – if there

Palate – Even if they didn’t say so on the label, I’d say this is almost completely Guyanese just because of the way all the standard wooden-still tastes are so forcefully put on show – if there

Nose – Quite a bit different from the strongly focussed Demerara profile of the Navy 70º we looked at before – had the label not been clear what was in it, I would have not guessed there was any Jamaican in here. The wooden stills profile of Guyana is tamed, and the aromas are prunes, licorice, black grapes and a light brininess. After a while some salt caramel ice cream, nougat, toffee and anise become more evident. Sharp fruits are held way back and given the absence of any kind of tarriness, I’d hazard that Angostura provided the Trinidadian component.

Nose – Quite a bit different from the strongly focussed Demerara profile of the Navy 70º we looked at before – had the label not been clear what was in it, I would have not guessed there was any Jamaican in here. The wooden stills profile of Guyana is tamed, and the aromas are prunes, licorice, black grapes and a light brininess. After a while some salt caramel ice cream, nougat, toffee and anise become more evident. Sharp fruits are held way back and given the absence of any kind of tarriness, I’d hazard that Angostura provided the Trinidadian component.

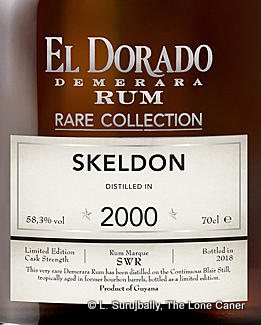

Its standout aspect was how smooth it came across when tasted. As with the Albion we looked at before, the rum didn’t profile like anywhere near its true strength, was warm and firm and tasty, trending a bit towards being over-oaked and ever-so-slightly too tannic. But those powerful notes of unsweetened cooking chocolate, creme brulee, caramel, dulce de leche, molasses and cumin mitigated the wooden bite and provided a solid counterpoint into which subtler marzipan and mint-chocolate hints could be occasionally noticed, flitting quietly in and out. The finish continued these aspects while gradually fading out, and with some patience and concentration, port-flavoured tobacco, brown sugar and cumin could be discerned.

Its standout aspect was how smooth it came across when tasted. As with the Albion we looked at before, the rum didn’t profile like anywhere near its true strength, was warm and firm and tasty, trending a bit towards being over-oaked and ever-so-slightly too tannic. But those powerful notes of unsweetened cooking chocolate, creme brulee, caramel, dulce de leche, molasses and cumin mitigated the wooden bite and provided a solid counterpoint into which subtler marzipan and mint-chocolate hints could be occasionally noticed, flitting quietly in and out. The finish continued these aspects while gradually fading out, and with some patience and concentration, port-flavoured tobacco, brown sugar and cumin could be discerned.

Rumaniacs Review #107 | R-0688

Rumaniacs Review #107 | R-0688 Palate – Waiting for this to open up is definitely the way to go, because with some patience, the bags of funk, soda pop, nail polish, red and yellow overripe fruits, grapes and raisins just become a taste avalanche across the tongue. It’s a very solid series of tastes, firm but not sharp unless you gulp it (not recommended) and once you get used to it, it settles down well to just providing every smidgen of taste of which it is capable.

Palate – Waiting for this to open up is definitely the way to go, because with some patience, the bags of funk, soda pop, nail polish, red and yellow overripe fruits, grapes and raisins just become a taste avalanche across the tongue. It’s a very solid series of tastes, firm but not sharp unless you gulp it (not recommended) and once you get used to it, it settles down well to just providing every smidgen of taste of which it is capable.