There was a lot of rum floating around Italy in the post-WW2 years, but not all of it was “real” rum; much was doctored miscellaneous plonk based on neutral alcohol. I tried some a few times, but a brief foursome with a trio of Italian Rum Fantasias from the 1950s, carelessly indulged in back when I was young and irresponsible, left me, as all such things do, with little beyond guilt, a headache and a desperate need for water. Even way back then — when I knew less but thought I knew more — I was less than impressed with what those alcoholic drinks had to offer. I’m unsure whether this rum qualifies as one such, but it conforms to the type enough that mention at least has to be made.

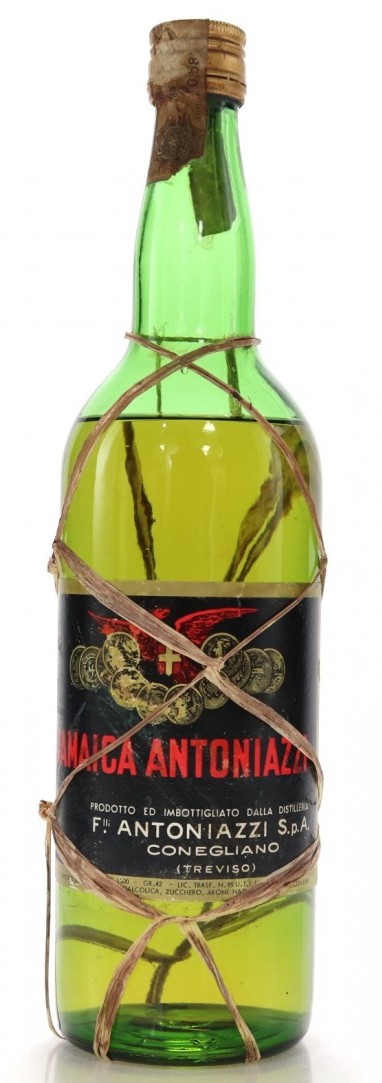

The company of the Antoniazzi Brothers operated out of the small northeast-Italian town of Conegliano, in the county of Treviso. Initially my researches showed they were in existence in the 1950s, which suggests they were formed in the post war years as spirits merchants. But it became clear that not only had they been active in 1926 as grappa makers – the region is famous for the product, so that makes sense – but a document from 1950 shows on the letterhead that they had been founded in 1881. Who the founder was, who the sons were and the detailed history of the company will have to wait for a more persevering sleuth.

Still, here’s what we can surmise: they probably started as minor spirits dealers, specialising in grappa and expanded into brandies and cognacs. In the 1950s onwards, as Italy recovered from the second World War, they experimented with Fantasias and liqueurs and other flavoured spirits, and by the 1970s their stable had grown quite substantially: under their own house label, they released rum, amaretto, brandy, sambuca, liqueurs, gin, scotch, whiskey, grappa, anise and who knows what else. By the turn of the century, the company had all but vanished and nowadays the name “Antoniazzi” leads to legal firms, financial services houses, and various other dead ends…but no spirits broker, merchant, wine dealer or distiller. From what others told me, the spirits company folded by the 1980s.

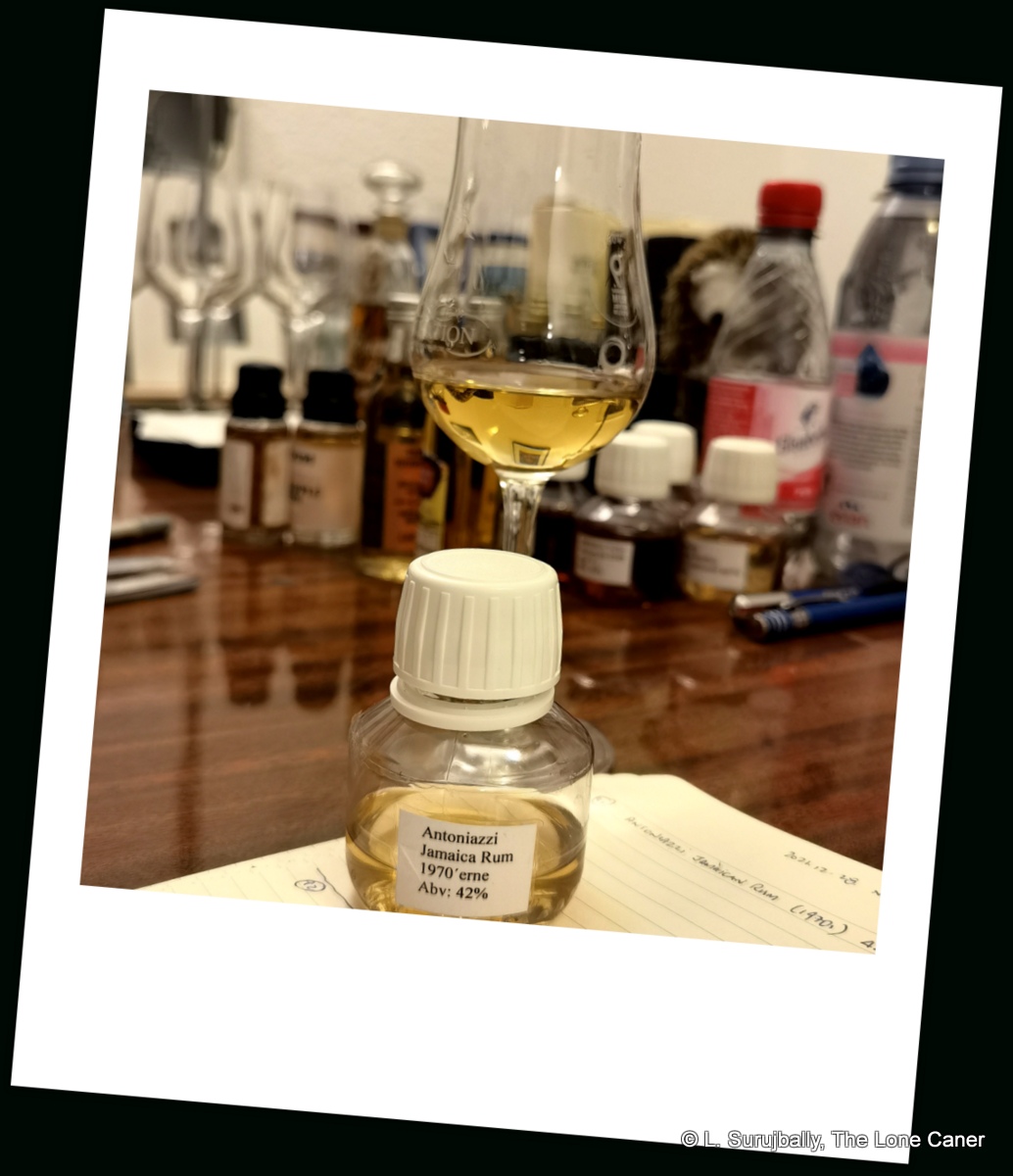

Strength – 42%

Nose – Very light and floral, with bags of easy-going ripe white fruits; not tart precisely, or overly acidic; more creamy and noses like an amalgam of unsweetened yoghurt, almonds, valla essence and white chocolate. There’s also icing sugar and a cheesecake with some lemon peel, with a fair bit of vanilla becoming more overpowering the longer the rum stays open.

Palate – Floral and herbal notes predominate, and the rum turns oddly dry when tasted, accompanied by a quick sharp twitch of heat. Tastes mostly of old oranges and bananas beginning to go, plus vanilla, lemon flavoured cheesecake, yoghurt, Philly cheese and the vague heavy bitterness of salt butter on over-toasted black bread.

Finish – Nice, flavourful and surprisingly extended, just not much there aside from some faint hints of key lime pie, guavas, green tea and flambeed bananas. And, of course, more vanilla.

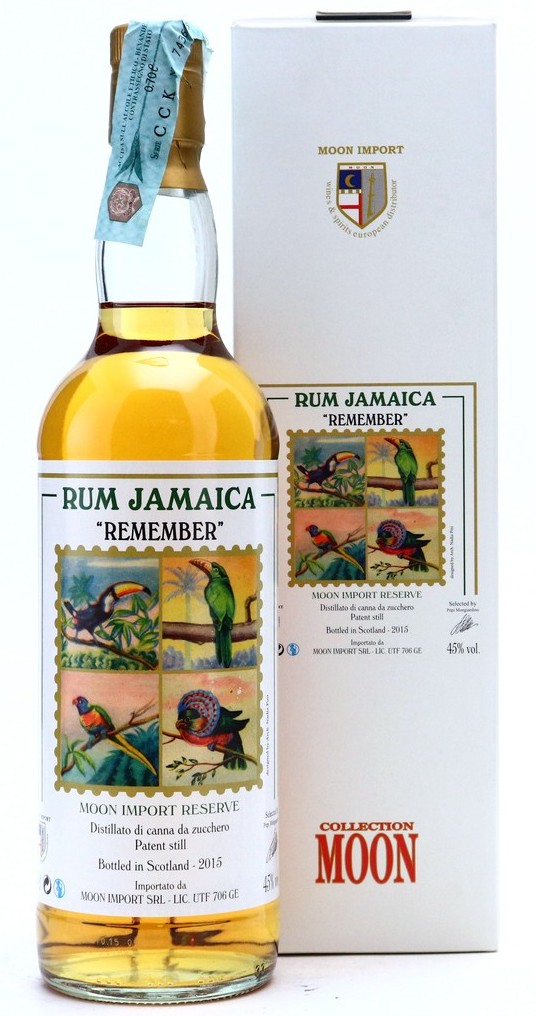

Thoughts – It starts well, but overall there’s not much to the experience after a few minutes. Whatever Jamaican-ness was in here has long since gone leaving only memories, because funk is mostly absent and it actually has the light and crisp flowery aromatic notes that resemble an agricole. The New Jamaicans were far in the future when this thing was made, yet even so, this golden oldie isn’t entirely a write off like so many others from the era.

(82/100) ⭐⭐⭐½

Other Notes

- 2024 Video Recap here.

- Hat tip to Luca Gargano and Fabio Rossi, and a huge thank you to Pietro Caputo – these gentlemen were invaluable in providing information about the Antoniazzi history.

- Hydrometer gauged this as 40.1% ABV which equates to about 7-8g/L of adulteration. Not much, but something is there.

- Source estate unknown, still unknown, ageing unknown

“Fantasias”

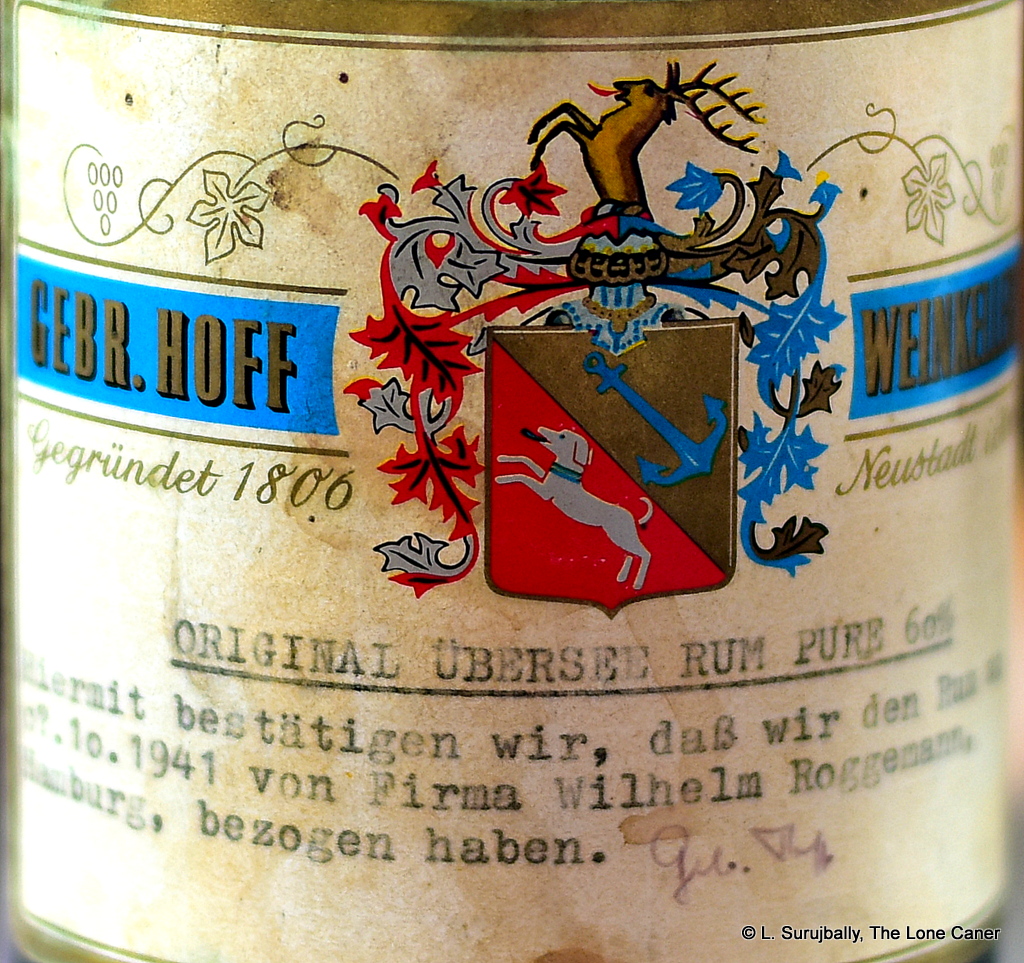

Rhum Fantasias were to be found in the 1950s through the 1970s as the Italian versions of Vershnitt or Inlander (domestic) rums such as had been popular in Germany in the 1800s and early 1900s (they may have existed earlier, but I never found any). This class of spirits remains a brisk seller in eastern Europe: Tuzemak, Casino 50º and Badel Domaci, as well as today’s flavoured spirits, are the style’s modern inheritors. They were mostly neutral alcohol – vodka, to some – to which some level of infusion, flavouring or spices were added to give it a pleasant taste. To the modern drinker they would be considered weak, insipid, over-flavoured, over-sugared, and lacking any kind of rum character altogether. Fifty years ago when most people didn’t even know about the French islands’ rums, Jamaica and Barbados were the epitome of ‘exotic’ and Bacardi ruled with a light-rum-mailed first, they were much more popular.

So let’s try it and see. Nose is, let me state right out, great. Sure, it’s rather rough and ready, spurring and booting around, but nicely rich and deep with initial aromas of butterscotch, caramel, brine, molasses. A nice dry and dusty old cardboard smell is exuded, and then a whiff of rotten fruits – and, as the Jamaicans have taught us, this is not necessarily a bad thing – to which is gradually added a fruity tinned cherry syrup, coconut shavings and vanilla. A few prunes and ripe peaches. Hints of glue, brine, humus and olive oil. It smells both musky and sweet, with anise popping in and out like a jack in the box. Glue, brine, humus and olive oil. So all in all, a lot going on in there, all nicely handled.

So let’s try it and see. Nose is, let me state right out, great. Sure, it’s rather rough and ready, spurring and booting around, but nicely rich and deep with initial aromas of butterscotch, caramel, brine, molasses. A nice dry and dusty old cardboard smell is exuded, and then a whiff of rotten fruits – and, as the Jamaicans have taught us, this is not necessarily a bad thing – to which is gradually added a fruity tinned cherry syrup, coconut shavings and vanilla. A few prunes and ripe peaches. Hints of glue, brine, humus and olive oil. It smells both musky and sweet, with anise popping in and out like a jack in the box. Glue, brine, humus and olive oil. So all in all, a lot going on in there, all nicely handled. Rumaniacs Review #123 | #800

Rumaniacs Review #123 | #800

But a gent called

But a gent called

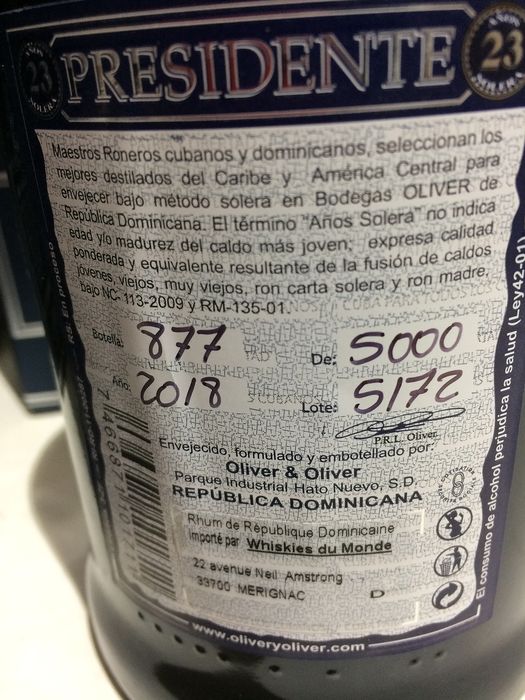

It gets no better when tasted. It’s very darkly sweet, liqueur-like, giving up flavours of prunes and stewed apples (again); dates; peaches in syrup, yes, more syrup, vanilla and a touch of cocoa. Honey, Cointreau, and both cloying and wispy at the same time, with a last gasp of caramel and toffee. The finish is thankfully short, sweet, thin, faint, nothing new except maybe some creme brulee. It’s a rum that, in spite of its big number and heroic Jose Marti visage screams neither quality or complexity. Mostly it yawns “boring!”

It gets no better when tasted. It’s very darkly sweet, liqueur-like, giving up flavours of prunes and stewed apples (again); dates; peaches in syrup, yes, more syrup, vanilla and a touch of cocoa. Honey, Cointreau, and both cloying and wispy at the same time, with a last gasp of caramel and toffee. The finish is thankfully short, sweet, thin, faint, nothing new except maybe some creme brulee. It’s a rum that, in spite of its big number and heroic Jose Marti visage screams neither quality or complexity. Mostly it yawns “boring!”

Or so the story-teller in me supposes. Because all jokes and anecdotes aside, what this is, is a rum made to order.

Or so the story-teller in me supposes. Because all jokes and anecdotes aside, what this is, is a rum made to order.

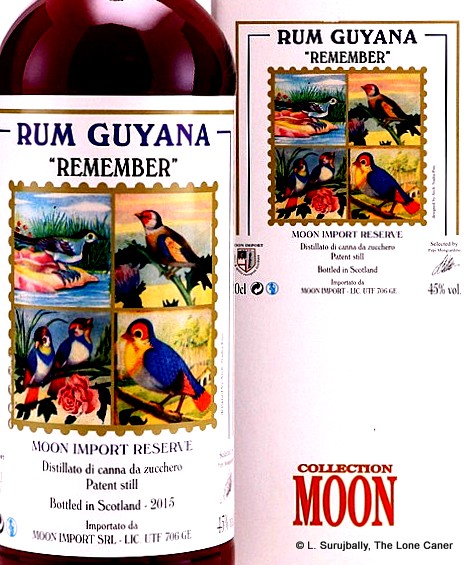

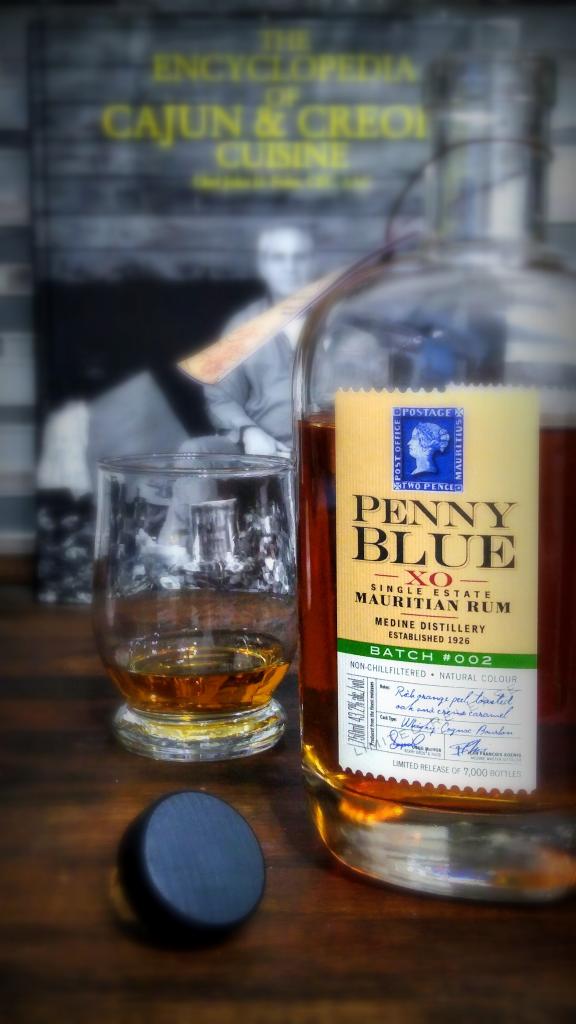

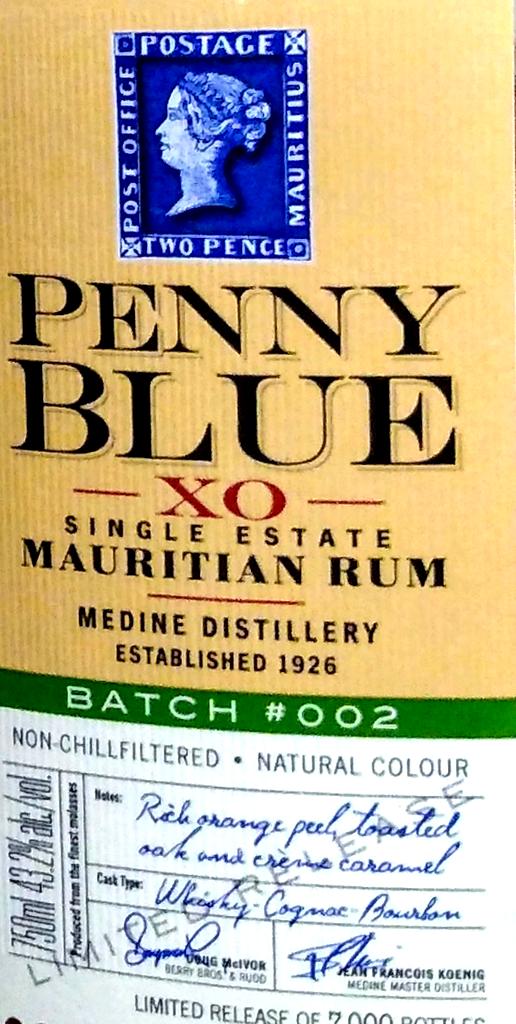

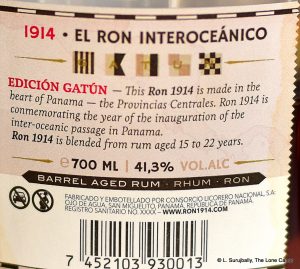

This process provides a tasting profile that reminds me of nothing so much than a slightly addled wooden still-rum from El Dorado: it’s sweet, feels the slightest bit sticky, and has strong notes of dark fruits, red licorice, plums, raisins and an almond chocolate bar gone soft in the heat. There’s other stuff in there as well – some caramel, vanilla, pepper again, light orange peel, but overall the whole thing is not particularly complex, and it ambles easily towards a short and gentle finish of no particular distinction that pretty much displays some dark fruit, caramel, anise and molasses, and that’s about it.

This process provides a tasting profile that reminds me of nothing so much than a slightly addled wooden still-rum from El Dorado: it’s sweet, feels the slightest bit sticky, and has strong notes of dark fruits, red licorice, plums, raisins and an almond chocolate bar gone soft in the heat. There’s other stuff in there as well – some caramel, vanilla, pepper again, light orange peel, but overall the whole thing is not particularly complex, and it ambles easily towards a short and gentle finish of no particular distinction that pretty much displays some dark fruit, caramel, anise and molasses, and that’s about it. So, until we know more, focus on the rum itself. It’s quiet and gentle and some cask strength lovers might say – not without justification – that it’s insipid. It has some good tastes, simple but okay, and hews to a profile with which we’re not entirely unfamiliar. It has a few off notes and a peculiar substrate of something different, which is a good thing. So in the end,

So, until we know more, focus on the rum itself. It’s quiet and gentle and some cask strength lovers might say – not without justification – that it’s insipid. It has some good tastes, simple but okay, and hews to a profile with which we’re not entirely unfamiliar. It has a few off notes and a peculiar substrate of something different, which is a good thing. So in the end,

Colour – Gold brown

Colour – Gold brown

It is, in short, a powerful wooden fruit bomb, one which initially sits and broods in the glass, dark and menacing, and needs to sit and breathe for a while. Fumes of prunes, plums, blackcurrants and raspberries rise as if from a grumbling and stuttering half-dormant volcano, moderated by tarter, sharper flavours of damp, sweet, wine-infused tobacco, bitter chocolate, ginger and anise. The aromas are so deep it’s hard to believe it’s so young — the distillate is aged around five years or less in Guyana as far as I know, then shipped in bulk to the USA for bottling. But aromatic it is, to a fault.

It is, in short, a powerful wooden fruit bomb, one which initially sits and broods in the glass, dark and menacing, and needs to sit and breathe for a while. Fumes of prunes, plums, blackcurrants and raspberries rise as if from a grumbling and stuttering half-dormant volcano, moderated by tarter, sharper flavours of damp, sweet, wine-infused tobacco, bitter chocolate, ginger and anise. The aromas are so deep it’s hard to believe it’s so young — the distillate is aged around five years or less in Guyana as far as I know, then shipped in bulk to the USA for bottling. But aromatic it is, to a fault.

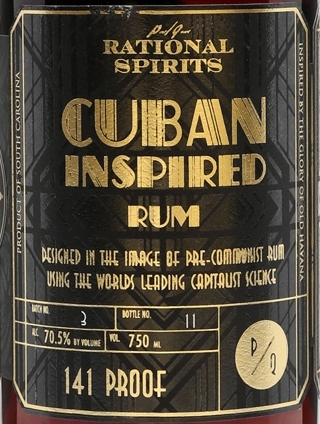

Normally, such a rum wouldn’t interest me much, but with the massive reputations the New Jamaicans have been building for themselves, it made me curious so I grudgingly parted with some coin to get a sample. That was the right decision, because this thing turned out to be less an undiscovered steal than a low-rent Jamaican wannabe for those who don’t care about and can’t tell one Jamaican rum from another, know Appleton and stop there. The rum takes great care not to go beyond such vanilla illusions, since originality is not its forte and it takes inoffensive pleasing-the-sipper as its highest goal.

Normally, such a rum wouldn’t interest me much, but with the massive reputations the New Jamaicans have been building for themselves, it made me curious so I grudgingly parted with some coin to get a sample. That was the right decision, because this thing turned out to be less an undiscovered steal than a low-rent Jamaican wannabe for those who don’t care about and can’t tell one Jamaican rum from another, know Appleton and stop there. The rum takes great care not to go beyond such vanilla illusions, since originality is not its forte and it takes inoffensive pleasing-the-sipper as its highest goal.

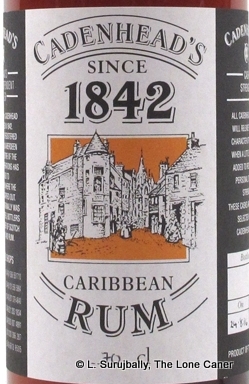

Watson’s Trawler rum, bottled at 40% is another sprig off that branch of British Caribbean blends, budding off the enormous tree of rums the empire produced. The company, according to Anne Watson (granddaughter of the founder), was formed in the late 1940s in Aberdeen, sold at some point to the Chivas Group, and since 1996 the brand is owned by Ian McLeod distillers (home of Sheep Dip and Glengoyne whiskies). It remains a simple, easy to drink and affordable nip, a casual drink, and should be approached in precisely that spirit, not as something with pretensions of grandeur.

Watson’s Trawler rum, bottled at 40% is another sprig off that branch of British Caribbean blends, budding off the enormous tree of rums the empire produced. The company, according to Anne Watson (granddaughter of the founder), was formed in the late 1940s in Aberdeen, sold at some point to the Chivas Group, and since 1996 the brand is owned by Ian McLeod distillers (home of Sheep Dip and Glengoyne whiskies). It remains a simple, easy to drink and affordable nip, a casual drink, and should be approached in precisely that spirit, not as something with pretensions of grandeur. It’s in that simplicity, I argue, lies much of Watson’s strength and enduring appeal — “an honest and loyal rum” opined

It’s in that simplicity, I argue, lies much of Watson’s strength and enduring appeal — “an honest and loyal rum” opined  Rumaniacs Review #119 | 0756

Rumaniacs Review #119 | 0756 Colour – Dark gold

Colour – Dark gold Rumaniacs Review #118 | 0755

Rumaniacs Review #118 | 0755 Colour – Mahogany

Colour – Mahogany