This is a completely theoretical “what-if?” about the implications for the rum world if the technological process of superfast ageing were ever to be perfected.

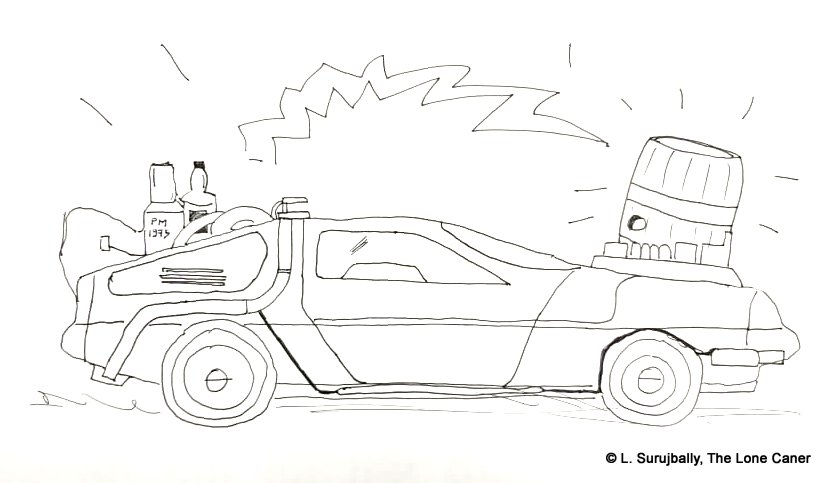

Ever since ageing of spirits became a thing, people have been trying to make it faster in a sort of half-assed time-travel wish-fulfilment. They’ve tried the adding of wood chips, smaller barrels, keeping the barrels in motion, dosage, temperature control, music, ultrasound, etc etc – all in an effort to have the taste of a 20 year old rum stuffed inside a spirit made the day before yesterday.

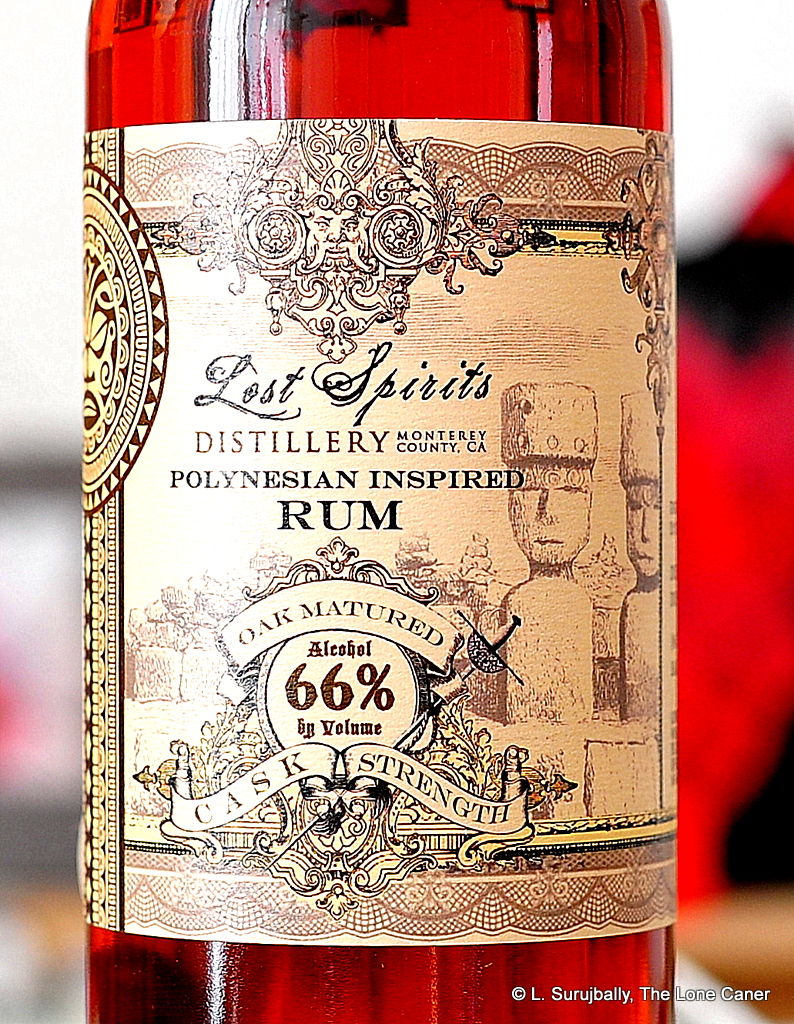

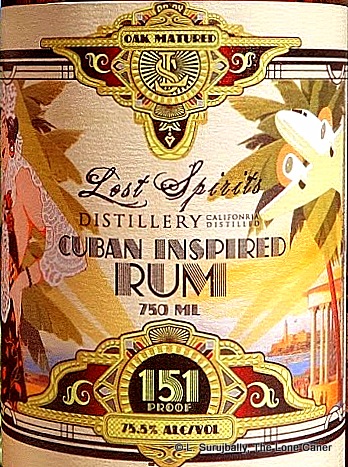

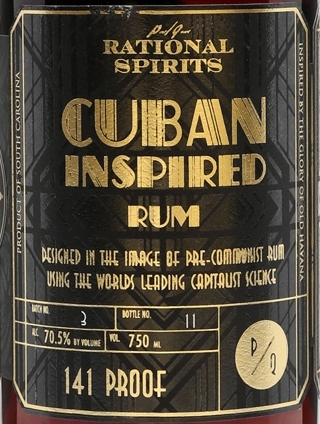

Take Rational Spirits’ Cuban Inspired rum I wrote about recently, and the NYT article on research into the field. That rum was itself based on technology Bryan Davis of Lost Spirits had developed years earlier (he is mentioned in the NYT piece) where he was trying to do exactly that…accelerate the change in taste profile of selected spirits, to mimic that created by many years of ageing.

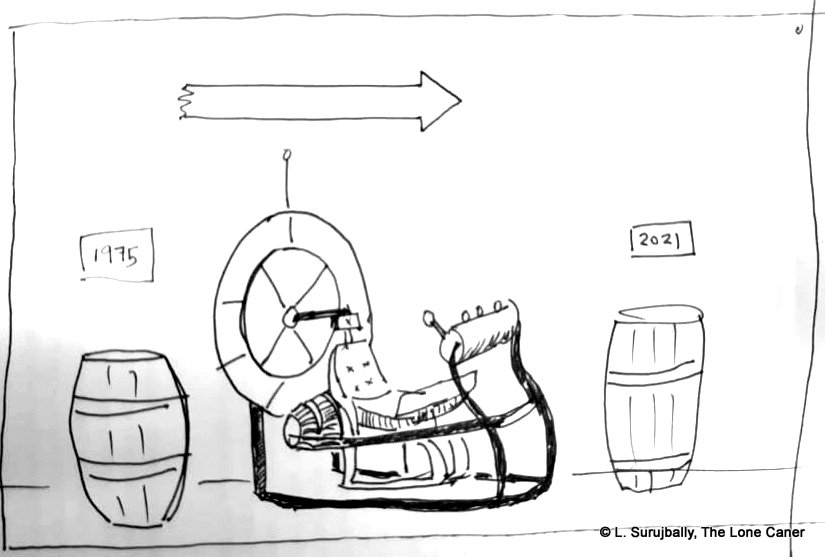

I’ve never stopped thinking about what such a technology might actually imply – particularly the outcomes. Because I think that the state of modern chemical and physical technology is such that even with all the thousands or millions – or billions – of disparate variables that interact in such complex ways to create the taste of a seriously aged rum, it may possible, just possible — not now, but someday — to get close to a 1975 Port Mourant…and do it in a few days. And what that implies for the industry should be considered.

Here, I won’t go into the methods and processes various companies have developed: what interests me is what the success of such a process might mean, the impacts it would have…if it were a reality. For the purpose of this what-if article, I am taking “the process” to mean not just being able to produce an ersatz aged product in a very short time…but any profile at will (it is part of the same idea, after all, so one inevitably follows the other).

And thinking of that leads down some interesting paths.

Obviously, first and foremost is money. All input costs gathered post-distillation get reduced with a process that can do “ageing on demand” – most especially the warehousing charges of storing barrels for years or decades. Moreover, if one can produce an aged profile in days, oak barrels would be an unnecessary expense since storage could be in larger, inert vats made of steel or even (heaven forbid) plastic – the profile is already “set” so why bother going further with real barrels? Warehousing overheads would be reduced both for the physical infrastructure and its utilities, and the staffing.

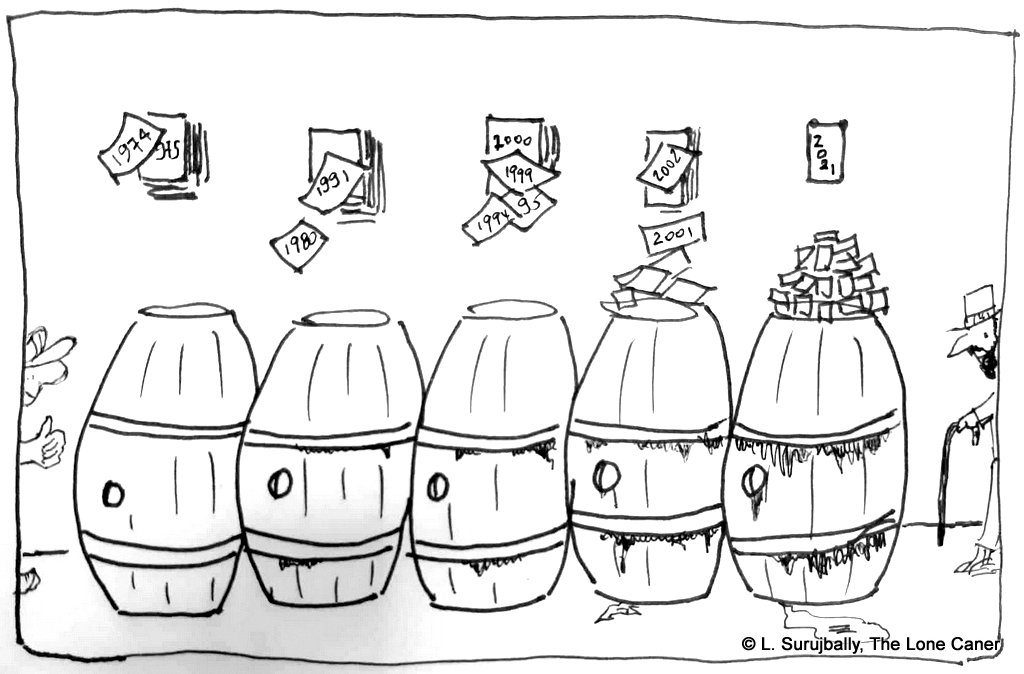

Too, if any superfast ageing process can happen, then clearly the angel’s share would shrink to nothing, which would leave more available to be sold. Inevitably, this would have a knock-on negative effect on prices. One of the reasons legends like the the Skeldon 1973 is so expensive is because it was issued at an incredible age which probably left less than 5% of the initial volume available for bottling – can you imagine five thousand bottles of this stuff being available instead of five hundred, and not having to wait 32 years to get it? The four figure prices it commands now would take a nose-dive.

In point of fact, such a process, since it could theoretically be done just about anywhere and replicate any rum’s profile, would instantly render the distinction between tropical and continental ageing nearly irrelevant. The ripple effects of what “pure” rum would mean under such circumstances are huge even beyond that – because if you could not tell the difference between an aged Foursquare produced in situ and a fake that someone else can produce by just dialling in some coordinates on a reactor, the entire business model of premiumization premised on GIs, terroire and island specific profiles is going to be disembowelled. Why pay a hundred bucks for a Hampden Great House when you can get the same thing (or an indistinguishable thing) made down the street for ten?

Tony Sachs, who touched on this topic back in 2015, suggested that it would primarily affect the smaller producers, who would be able to produce a better rum for less money, instead of having capital tied up in ageing inventory and having to sell sub-par young juice to make cash flow. But he also remarked that larger producers could make better “bottom-shelf” booze as well, and experimentation, being made simpler and faster with this tech, would allow profiles to be tested and produced on a much faster cycle than now. Nobody would be immune from this if they wanted to stay in the running. A lot of the same points were made in two FB conversations around the same time, in the Global Rum Club and La Confrerie du Rhum – and to this date, none of these issues have gone away (or been discussed beyond the superficialities).

Unsurprisingly, the industry commentators so far remain sanguine, relying on brand awareness, their names, the reputation built over decades, even centuries, the skill of their master distillers, blenders and cellar masters. “Old fashioned craft rum,” said one producer when commenting on superfast ageing several years ago, “Will always be there.” He’s probably right but at what level of production, I wonder, when faced with such a disruptor? The impacts I’ve described (or others I haven’t thought of) may not come to pass, but have not really been considered, largely because nobody takes this technology seriously: and with good reason, since so far it has not been shown to work. Nor, in spite of its application to some rums like Lost Spirits,’ has it succeeded in producing a rum the hype leads us to expect. In other words, the process is not making rums to upend the industry.

A successful technology would, however, force traditional mid-sized rum producers to adapt to a major change in their pricing models and sales strategies. Faced with a technology that would provide real price competition and render their carefully blended aged products less desirable (because a similar product could now be had for less), they would have to up their game by making new and different and (hopefully) even better rums, and to make them in such a way as to hobble any attempts at mimicry by such a process. This would cost them money.

It’s clear why labelling redesign and better disclosure are going to be required….

They would have to advertise differently, focus on their own premium-ness, the genuine nature of their products as opposed to the ersatz lab rats that are coming on the market. You can see this happening with mid sized “country-level” producers now, as they combat cheap US, Indian or Asian rums on the world market, or mass produced rums made by huge multi-column operations like Florida Distillers or those in Panama and elsewhere.

Distinctions between a “manufactured” rum made by a process of this kind, and a traditionally made one, would take on much greater importance, and that would logically lead to the courts. It is very likely that laws – or at least regulations by industry bodies – would be passed regarding advertising and restricting the labelling of such manufactured rums; they would not be able to pass themselves off as the genuine article. GIs would be amended to exclude fake-aged, or processed rums. Social media personages and little online armies would be mobilized by at-risk producers to wage a war of opinion and words against such upstarts (we have seen this already in other areas of the rum world).

The word “ageing” itself would have to be more rigorously defined and enshrined in legislation. If I set up my equipment in Bridgetown, buy unaged bulk rum from any of the distilleries and then run it through the process at half the cost, you’d better believe I can call it a NAS Barbados rum under the current rules, and that means post-distillation processes have to be re-specified and redrafted to stop me from undercutting their prices for what they make and taking away their market share. Moreover, some way of trademarking or patenting the taste profile of a rum from one specific still, distillery or country is going to have to be found and distinguished, because the technology would instantly make counterfeiting and copying known brands a huge issue.

Multinational spirits conglomerates are likely to jump on board with this as well. Since they go after bulk sales of cheap one-for-everyone commercial products whose margins are thinner, anything that reduces costs, or increases quality for the same price, will be looked at and developed. They might even buy the technology from some small tech startup like Mr. Davis and scale it up to industrial proportions, at which point market dominance is a very real possibility and small producers would hit the wall.

Of course, the high end connoisseurship and chatterati would absolutely continue prefer and promote the true-made rum as opposed to any ersatz lab concoction (we see that already with dosed rums). But the painful truth is that such buyers, influencers, self-styled ambassadors and social media pundits, for all their noise, don’t actually account for much in the way of sales (otherwise Plantation and Flor de Cana would have gone belly-up years ago). The mid range and bottom shelf is where the vast majority of sales to the public lie – there is no significant, high-end premium market in existence (as there is, for example, in mechanical Swiss watches), just a marginal one.

What this means is that it won’t matter if famed famed distilleries and notables of the industry throw their weight behind artisanal rums – if the cost is low and the quality is good enough, the majority of rum drinkers (who know little and care less about the rum wars others fight on their behalf) will continue to not just go for Bacardi but a low end ersatz Bacardi copy at an even lower price. We won’t even go into the inevitable scourge of counterfeiting that is sure to start if any profile can be replicated at will.

This leads, then, to the possibility that the industry might for the first time require a global controlling body to set proper standards for production and labelling, national and international enforcement with teeth, and to find room for such a manufactured product that can separate it out and classify it in a way that makes its nature pellucidly clear. The dog eat dog nature of spirits production, so tied up in national pride and economics, has so far resisted this kind of move, but I submit that under the pressure of a potentially mould-breaking force, it may become inevitable.

Admittedly, I paint a blue-sky picture of massive disruption here, based on a technology that is far from proven and does not currently exist in the form I posit. So far, none of it has happened, and the earth keeps on spinning as it always has. And as others have pointed out, should such a process or the technology be perfected, it would make the bottom shelf better and the top end cheaper.

In any case, as has been constantly and comfortingly stated, people also do love the genuine article. I have heard no end of statements that people will always prefer the depth and rounded flavour and complexity of a natural, true-aged rum. And that’s completely true…for rums they can get, and afford. But what happens to rums that are out of production but desperately sought after? Rums made in limited quantities? That are too expensive? The Saint James 1885 comes to mind, and we won’t even talk about the Harewood House rum from 1780.

The technology’s research and the articles written about it, is currently and mostly aimed at two aspects of the spirits world: one, to provide an aged profile without actually ageing anything (for costs reduction), and two, to recreate old marks that can be sold for high prices (for revenue enhancement).

Rational Spirits with its Cuban Inspired rum, and Lost Spirits before them with their Navy, Polynesian and Colonial rums, went the route of re-creation. But that created a third additional issue not often articulated, which most commentators (who only focus on the first thing, ageing) never address. And that’s who to sell the recreated dead marks to.

It’s a reasonable question because consider: so few such “dead” rums remain and so few people exist who could actually describe the taste accurately (let alone write about it or have the nostalgia to get one), that you could just as easily do any old thing and say it was a faithful replica, call it “inspired” and who would gainsay you? At best such a duplicated re-creation owes its sales to marketing, curiosity or nostalgia. It’s not really geared or guaranteed to provide a long term market or massive sales. A duplicate does not become a sought-after classic. No aged replica could ever have serious street cred – buyers would be unable to say it was genuine and pricing would be a problem. This thing such companies have, that they want to recreate halo-marks of yesteryear, lost or dead, therefore, strikes me as no more than a marketing game and ultimately a dead end.

***

What this all in some way leads up to, then is my belief that the real potential of such a process is not in the duplication of past profiles, or even the faux-ageing that nobody will ever take seriously, can’t be proven and can’t be labelled as such. Today’s drinking class don’t give a good goddamn about some Farrell’s Montserrat rum from the 1950s, Trader Vic’s Appleton 17 YO, or even a Caputo 1973 recreation.

What buyers want is the new Chairman’s Reserve at cask strength for five dollars. They’re after a Velier-Hampden Great House or HV Port Mourant White for ten bucks, and even more, would like to buy entire Foursquare ECS range available for only a Benjamin. That’s the third, ignored side of what such as-yet unproven technology would really entail, and all these companies doing research on different ways to flash age, re-create, re-do or re-invent are promoting the wrong aspect of their work. They keep trying to recreate something that doesn’t actually exist any more and bottle their results as an “Inspired” version.

The true, unspoken, unseen, undiscussed killer-app of any process of spirits alteration is in the recreation of what’s popular now. The proof of the pudding is whether they can recreate current marks which people can buy in the store and know really well, and do it so well that almost no-one — consumer, taster or expert — can tell the difference…and accepts the made product as indistinguishable from the real one. If the companies hustling to develop such techniques were ever to succeed at that, then they’d have my (and everyone else’s) serious attention…and upend the industry overnight.

However, so far that has not seemed to compute, so it’s replication and fast ageing that gets all the attention — and the real market disruptions I once thought Lost Spirits and all the other companies might herald, remain unrealized. For now, anyway.

And, as an old fashioned kind of rum guy who prefers the genuine article myself, I kind of hope it stays that way.

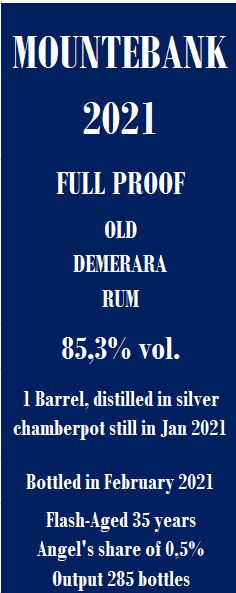

So let’s try it and see. Nose is, let me state right out, great. Sure, it’s rather rough and ready, spurring and booting around, but nicely rich and deep with initial aromas of butterscotch, caramel, brine, molasses. A nice dry and dusty old cardboard smell is exuded, and then a whiff of rotten fruits – and, as the Jamaicans have taught us, this is not necessarily a bad thing – to which is gradually added a fruity tinned cherry syrup, coconut shavings and vanilla. A few prunes and ripe peaches. Hints of glue, brine, humus and olive oil. It smells both musky and sweet, with anise popping in and out like a jack in the box. Glue, brine, humus and olive oil. So all in all, a lot going on in there, all nicely handled.

So let’s try it and see. Nose is, let me state right out, great. Sure, it’s rather rough and ready, spurring and booting around, but nicely rich and deep with initial aromas of butterscotch, caramel, brine, molasses. A nice dry and dusty old cardboard smell is exuded, and then a whiff of rotten fruits – and, as the Jamaicans have taught us, this is not necessarily a bad thing – to which is gradually added a fruity tinned cherry syrup, coconut shavings and vanilla. A few prunes and ripe peaches. Hints of glue, brine, humus and olive oil. It smells both musky and sweet, with anise popping in and out like a jack in the box. Glue, brine, humus and olive oil. So all in all, a lot going on in there, all nicely handled.