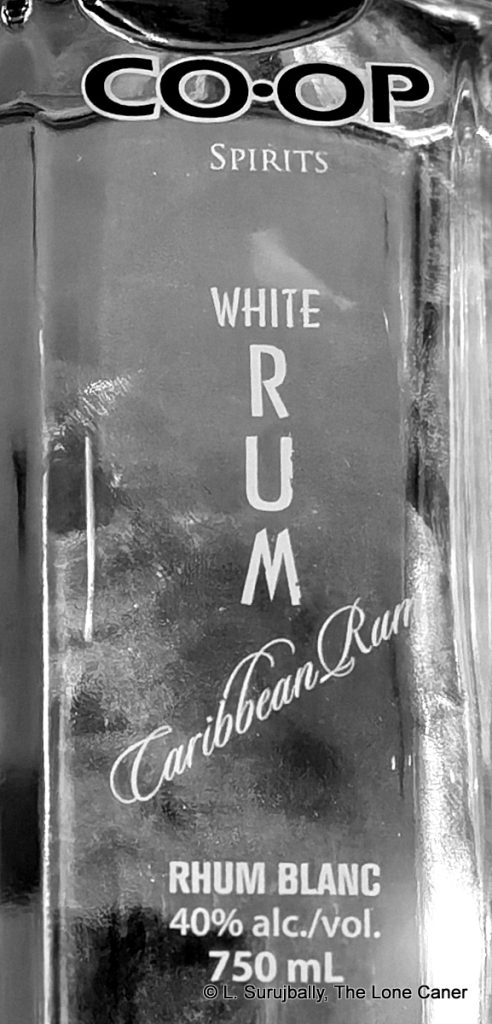

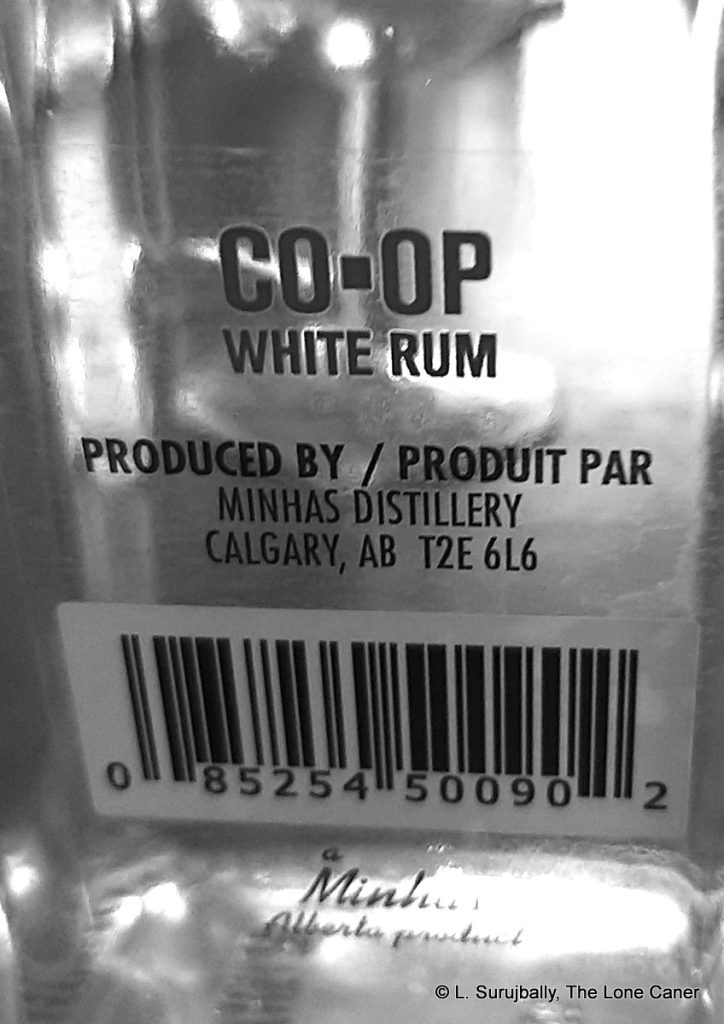

What we are trying today is the Co-Op Caribbean White Rum, which at around C$30 or less is comfortably within the reach of anyone’s purse if perhaps not their purpose. The rum is supplied to the Co-Op supermarket chain by a very interesting Calgary-based company called Minhas Distillery, which until recently didn’t have a distillery in the city, just a brewery, and whatever spirits they produced came from a distillery down in Wisconsin…which is all less than helpful in tracing the product since rum is really not in their portfolio.

What Co-op sells is a white rum in a sleek glass bottle, 40%, without any statement of origin beyond the “Minhas Distillery”. It is supposedly a Caribbean rum, yet no origin distillery is mentioned (let alone a country), and there’s no age, no still, no source material…in this day and age of full disclosure you almost have to admire the courage it takes to foist something so meaningless on the public and pretend it’s worth their coin. Admittedly though, none of this is necessarily a disqualification, because it could be a beast in disguise, a Hampden in hiding — for all we know, a few barrels could have been sourced under the table, or there could be a mad geeky rum nerd distiller lurking in the bowels of Minhas wielding dunder and lightning, ready to bring out the next Caribbean rum killing Canadian hooch.

Alas, sampling it dispels any such romantic notions in labba time. This so-called Caribbean rum is just shy of a one-note wonder. It is not fierce, given its living room strength, and does actually smell of something (which immediately marks it as better than the Merchant Shipping Co. White) – vanilla essence, and mothballs, coconut shavings, and lemon meringue pie. It smells rather sweet, there are some nice light floral hints here and there; and it has some crushed almond nuts smells floating around, yet there’s also a sort of odd papery dusty aroma surrounding it, almost but not quite like old clothes on a rack at a charity sale, and which reminds me of Johnson’s Baby Powder more than anything else (no, I’m not kidding).

Alas, sampling it dispels any such romantic notions in labba time. This so-called Caribbean rum is just shy of a one-note wonder. It is not fierce, given its living room strength, and does actually smell of something (which immediately marks it as better than the Merchant Shipping Co. White) – vanilla essence, and mothballs, coconut shavings, and lemon meringue pie. It smells rather sweet, there are some nice light floral hints here and there; and it has some crushed almond nuts smells floating around, yet there’s also a sort of odd papery dusty aroma surrounding it, almost but not quite like old clothes on a rack at a charity sale, and which reminds me of Johnson’s Baby Powder more than anything else (no, I’m not kidding).

The palate is where the ultimate falsity of all that preceded it snaps more clearly into focus. Flowers, lemon, even mothballs, all gone. The baby powder and old clothes have vanished. Like a siren luring you overboard and then showing its true face, the rum turns thin, harsh and medicinal when tasted, rough and sandpapery, mere alcohol is loosed upon the world and all you get is a faint taste of vanilla to make it all go down. Off and on for over an hour I kept coming back, but nothing further ever emerged, and the short, dusty, dry and sweet vanilla finish was the only other experience worthy of note here.

So. As a sipping rum, then it’s best left on the shelf. No real surprise here. As a mixer, I’m less sure, because it’s not a complete fail, but I do honestly wonder what it could be used for since there is so much better out there – even the Bacardi Superior, because at least that one has been made for so long that all the rough edges have been sanded off and it has a little bit of character that’s so sadly lacking and so sorely needed here.

There’s more than enough blame to go around with respect to this white rum, from Minhas on down to those bright shining lights in Co-Op’s purchasing and marketing departments (or, heaven help us, those directing the corporate strategy of what anonymous spirits to rebrand as company products), none of whom apparently have much of a clue what they’re doing when it comes to rum. It’s not enough that they don’t know what they’re making (or are too ashamed to actually tell us), but they haven’t even gone halfway to making something of even reasonable quality. It’s a cynical push of a substandard product to the masses – the idea of making a true premium product is apparently not part of the program.

In a way then, it’s probably best we don’t know what country or island or distillery or still this comes from: and I sure hope it’s some nameless, faceless corporate-run industrial multi-column factory complex somewhere. Because if Co-Op’s Caribbean white rum descends from stock sourced from any the great distilleries of the French islands, Barbados, Trinidad, St. Lucia, Guyana, Venezuela, Jamaica or Cuba (et al), and has been turned into this – whether through ignorance, inaction or intent– then all hope is lost, the battle is over, and we should all pack our bags and move to Europe.

(#984)(74/100) ⭐⭐½

Minhas is a medium-sized liquor conglomerate based on Calgary, and was founded in 1999 by Manjit Minhas and her brother Ravinder. She was 19 at the time, trained in the oil and gas industry as an engineer and had to sell her car to raise finance to buy the brewery, as they were turned down by traditional sources of capital (apparently their father, who since 1993 had run a chain of liquor stores across Alberta, would not or could not provide financing).

The initial purchase was the distillery and brewery in Wisconsin, and the company was first called Mountain Crest Liquors Inc. Its stated mission was to “create recipes and market high quality premium liquor and sell them at a discounted price in Alberta.” This enterprise proved so successful that a brewery in Calgary was bought in 2002 and currently the company consists of the Minhas Micro Brewery in the city (it now has distillation apparatus as well), and the brewery, distillery and winery in Wisconsin.

What is key about the company is that they are a full service provider. They have some ninety different brands of beers, spirits, liqueurs and wines, and the company produces brands such as Boxer’s beers, Punjabi rye whiskey, Polo Club Gin, and also does tequila, cider, hard lemonades. More importantly for this review, Minhas acts as a producer of private labels for Canadian and US chains as diverse as “Costco, Trader Joe’s, Walgreens, Aldi’s, Tesco/Fresh & Easy, Kum & Go, Superstore/Loblaws, Liquor Depot/Liquor Barn” (from their website). As a bespoke maker of liquors for third parties, Minhas caters to the middle and low end of the spirits market, and beer remains one of their top sellers, with sales across Canada, most of the USA, and around the world. So far, they have yet to break into the premium market for rums.

Other Notes

- I did contact them directly via social media and their site, and was directed via messenger to an email address that never responded to my queries on sourcing. However, after this post went up, Richard Seale of Foursquare got on to me via FB and left a comment that the distillate possibly came from WIRD (he himself had refused as the price they wanted was too low). The general claim on Minhas’s website is that their products are made with Alberta ingredients.

- It’s my supposition that there is some light ageing (a year or two), that it’s molasses based and column still distilled. It remains educated guesswork, however, not verified facts.

- Ms. Minhas’s father, having sold the liquor shops many years ago, has recently opened a large distillery in Saskatchewan with the same business model, but that is outside the scope of this article and so I have elected not to go into detail, and only include it here for completeness.

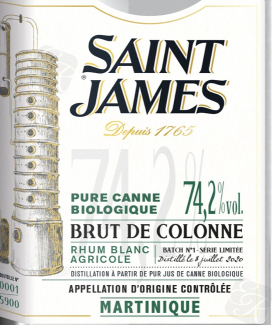

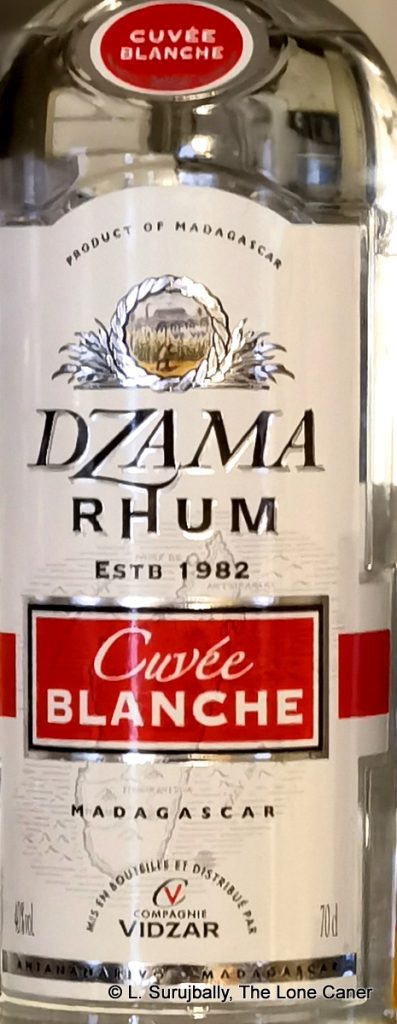

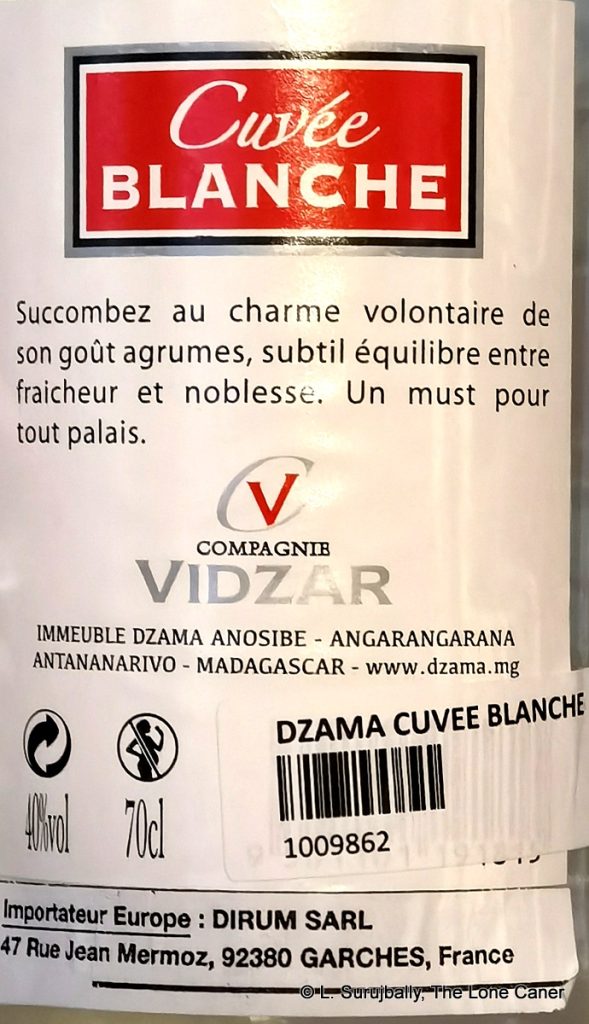

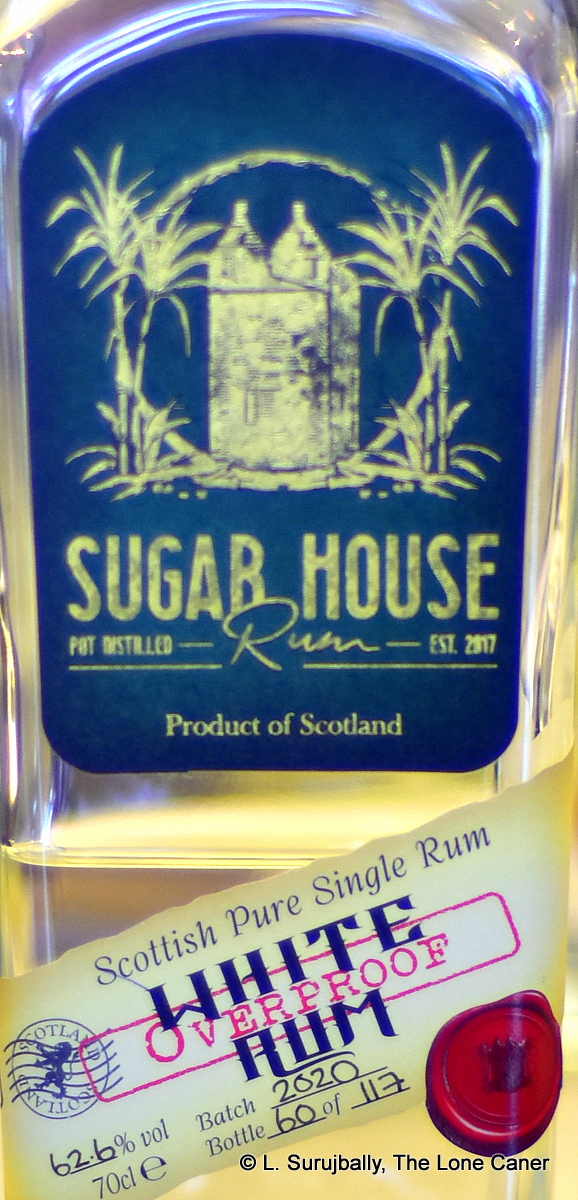

Now you would think that the producers of an overproof Wray-slaying-wannabe, which of course this aspires to be, would make every effort to ensure its product is packed with flavours of a fruit and candy shop and if it felt like being bellicose, pack itself with a nose the envy of a rutting troglodyte’s mouldy jockstrap. I stand here in front of you saying, with some surprise, that this just isn’t the case. The nose starts off okay, quite spicy, with notes of white chocolate, almonds, soy milk, creamy unsweetened yoghurt. Then it adds a bit of grass and cumin, a shaving of zest from a lime or two. A pear, maybe two, some papaya. But that’s about it. The rum is so peculiarly faint it’s like it would need to stand twice in the same place to make a shadow. This is an overproof? It’s more like slightly flavoured alcoholic water, and I say that with genuine regret.

Now you would think that the producers of an overproof Wray-slaying-wannabe, which of course this aspires to be, would make every effort to ensure its product is packed with flavours of a fruit and candy shop and if it felt like being bellicose, pack itself with a nose the envy of a rutting troglodyte’s mouldy jockstrap. I stand here in front of you saying, with some surprise, that this just isn’t the case. The nose starts off okay, quite spicy, with notes of white chocolate, almonds, soy milk, creamy unsweetened yoghurt. Then it adds a bit of grass and cumin, a shaving of zest from a lime or two. A pear, maybe two, some papaya. But that’s about it. The rum is so peculiarly faint it’s like it would need to stand twice in the same place to make a shadow. This is an overproof? It’s more like slightly flavoured alcoholic water, and I say that with genuine regret.