The “M&G” in the rhum’s title is not, as you might expect, the initials of the two founders of this small operation in Cabo Verde. In a lyrical twist, the letters actually stand for Musica e Grogue: Music and Grog. Which is original, if nothing else, because artistic touches are not all that common in our world, and such touches are often dismissed as mere frippery meant to distract from a substandard product.

In this case, however Jean-Pierre Engelbach, who founded the company with local Cabo Verde grogue producer and music-lover Simão Évora, has an interesting background in the dramatic and musical arts, and was a singer, comedian and director on the French scene for decades…one can only wonder what drove him to amend his career at this late stage by taking a sharp U turn and heading into the undiscovered country of grogues, but for my money, we should not quibble, but be grateful that another fascinating branch of the Great Rum Tree has come to our attention. For what it’s worth, he told me he fell in love with Cabo Verde music a long time ago, leading to visits and a growing appreciation and love for the local rhums and eventually the two men chose to entwine their passions in the name of the company.

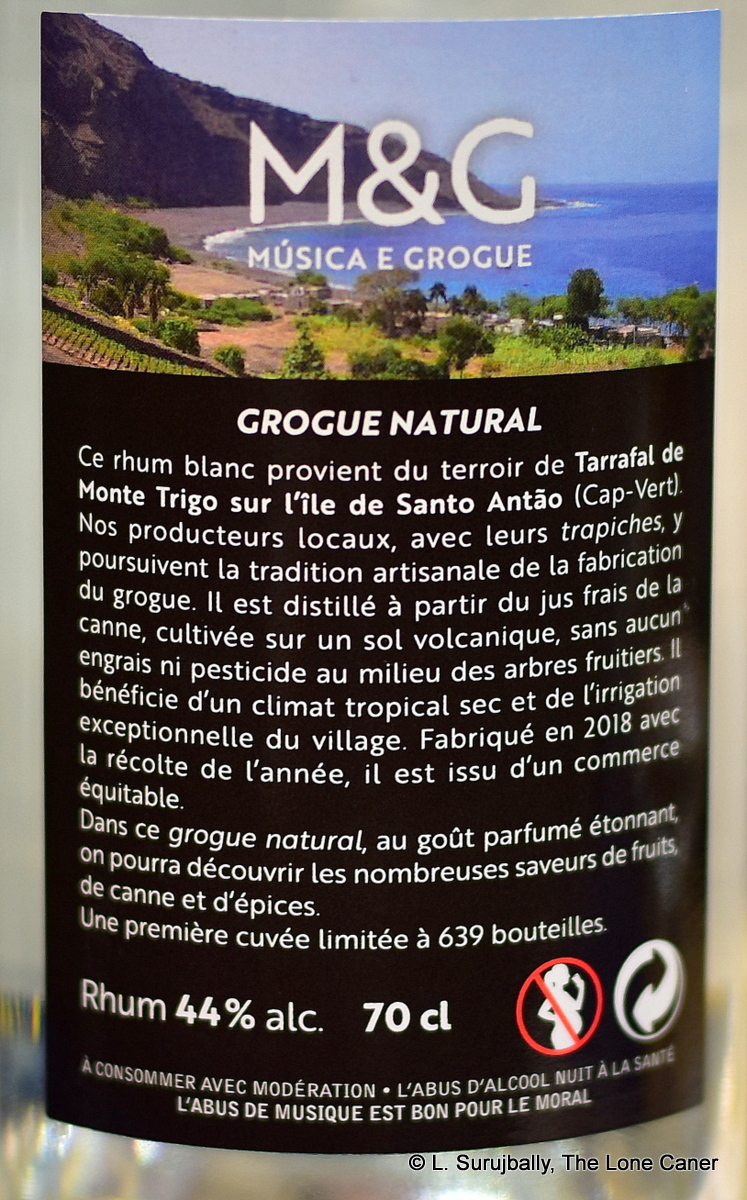

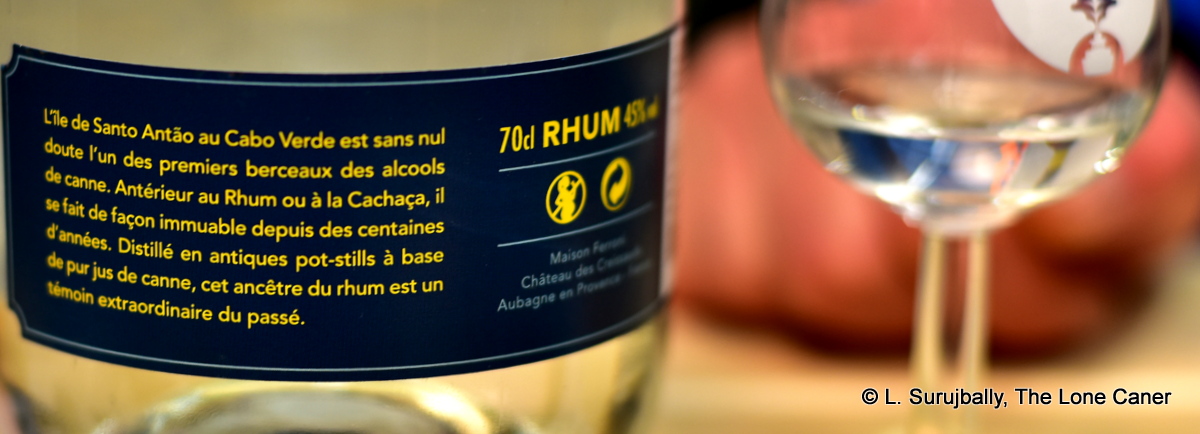

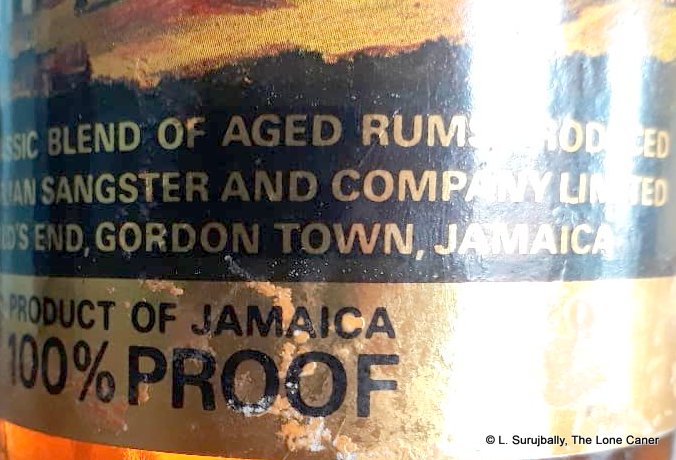

Anyway, this particular product is an unaged white, a grogue by the islands’ definitions (the only one that counts), derived from sugar cane in the Tarrafal village just south of Monte Trigo on the island of Santo Antão, the most north-westerly of the series of islands making up Cabo Verde..

Fire-fed pot still in Tarrafal. Photo (c) Musica e Grogue FB page

This one small village has five small artisanal distilleries (!!) that produce grogue in small quantities — about 20,000 liters annually — and M&G’s founders believe that the cane varietals there, combined with the climate and soil, produce a juice of exceptional quality. However, they only use a single preferred grogue-distiller for their juice, unlike Vulcão, also from here, which is a blend of three.

The production methods are straightforward: the cane, grown pesticide- and fertilizer-free, is crushed within 48 hours of harvesting, and fermentation is open air with natural from wild yeast for 10-15 days. The wash is then run through a fire-heated pot still, taken off at around 45% and is left to rest for a few weeks in 20 liter demi-johns known as a “Lady Jeanne” (also referred to as a Mama Juana or Dame Jeanne in Spanish and French speaking countries respectively). The peculiarity of this rest is that the large squat bottle in question is also stoppered with banana leaves, which “[…] allows the air to pass during the rest period of the grogue, necessary after the distillation,” said Jean-Pierre Engelbach, when I asked him.

Banana-leaf-stoppered demi-johns in which the grogue rests after distillation for 3-4 weeks. Photo (c) Musica e Grogue FB Page

That out of the way, what we had here, then, was a rhum made to many of the same general specifications as a French island agricole, while preserving its own unique production methodology and, hopefully, drinking profile. Did it succeed?

Oh yes. On smelling it for the first time, my initial notes read “subtly different” and within its strictures, it was. It initially seemed like a crisp-yet-gentle agricole, smelling cleanly of sweet sugar cane sap, vanilla, dill, green grapes and freshly mown grass, with a teasing note of brine and olives and a whiff of watered down vegetable soup fed to a jailbird in solitary. It was delicate and clear and different enough to hold the attention of anyone, nasal newbie or jaded rumdork, and the nice thing is, after five minutes it still was purring out aromas: flowers, cherries and pears, with a firm citrus line holding things together

While stronger and more individualistic drinks might be my personal preference these days, there was no denying that the Grogue Natural was a very pleasant drink, and I have a feeling I’ll be getting more of these things, as they provide a lovely counterpoint to agricoles in general. It tasted light, grassy, herbal, sweetish (without actually being sweet, if you catch my drift), with hints of watery sap, cane juice, cucumbers, an olive or two, and lots of light fruits – guavas, pears, soursop, ginnip, that kind of thing, and again, that lemon zest providing a clothesline on which to hang the lot. Finish was long and silky, surprising for something bottled at a modest 44%, but you don’t hear me complaining – it was just fine.

It’s become a sort of personal hobby for me to try unaged white rums of late, because while I love the uber-aged stuff, they do take flavours from the barrel and lose something of their original character, becoming delicious but changed spirits. On the other hand, unaged blancs or blancos — white rums — when not filtered to nothingness for the clueless, are about as close to pure and authentic rums as anyone’s going to get these days, and Cabo Verde’s stuff is among the most authentic of the lot.

It’s become a sort of personal hobby for me to try unaged white rums of late, because while I love the uber-aged stuff, they do take flavours from the barrel and lose something of their original character, becoming delicious but changed spirits. On the other hand, unaged blancs or blancos — white rums — when not filtered to nothingness for the clueless, are about as close to pure and authentic rums as anyone’s going to get these days, and Cabo Verde’s stuff is among the most authentic of the lot.

The Cap-Vert Grogue Natural that M. Jean-Pierre and Sr. Simão are making is one of these that need to be tried for that reason alone, quite aside from its overall drinkability. Sure it lacks the meticulous clarity of the French agricoles, and you’d never mistake it for a cachaca or a clairin or a Paranubes, but the relative isolation and old-style production methods of these music-loving Cabo Verde producers have assured us of a really interesting juice here, which deserves to become much more well known than it yet is. And drunk, of course. Yes. Preferably after a hard day’s work, as the sun goes down, while relaxing to the sounds of some really good island music.

(#634)(83/100)

Additional background

The company was formed in 2017 by the two gentlemen named above, who were drawn together by their mutual love of music and local rhum. But it was not until 2018 that they received the formal licenses permitting them to export grogues and started shipping some to Europe. This delay may have to do with the fact that hundreds of small moonshineries and primitive stills – nearly four hundred by one estimate – are scattered across Cabo Verde islands, with wildly varying quality of output. Indeed, according to one news report by the Expresso das Ilhas (Island Express), some 10 million liters of spirit calling it self “grogue” was marketed in 2017, but less than half of that could legitimately term itself so, since it was not made from sugar cane, and there were issues of hygiene and quality control to consider.

Be that as it may, M&G were able to navigate the new bureaucratic, quality and legal hurdles, obtain the requisite licenses and permits, and produced two grogues for the export market: the lightly-aged Velha we’ll be looking at soon, and the Natural.

Other Notes

- M&G and Vulcão are among the frist brands to export grogue from Cabo Verde

- M&G also makes some flavoured punches at a lower 18% strength

- Maison Ferroni, which is the brand owner for the Vulcão, is the distributor for M&G

- This bottle is part of the first release, and is something of a pilot project for the company’s export plans….hence the limited edition of 639 bottles. It’s not special per se, just part of a batch of the first four hundred liters or so which they exported.

- Back label translation:

This white rum comes from the Tarrafal terroir of Monte Trigo on the island of Santa Antao (Cape Verde). Our local producers, with their trapiches, continue the artisanal tradition of making grogue. It is distilled from fresh cane juice, cultivated on volcanic soil in the middle of fruit trees, without any fertilizer or pesticide. It benefits from a dry tropical climate and the exceptional irrigation of the village. Made in 2018 with the harvest of the year, it is a fair trade product.

In this natural grogue, with its amazing flavor, we can discover the many flavors of cane fruits and spices.

A first release limited to 639 bottles

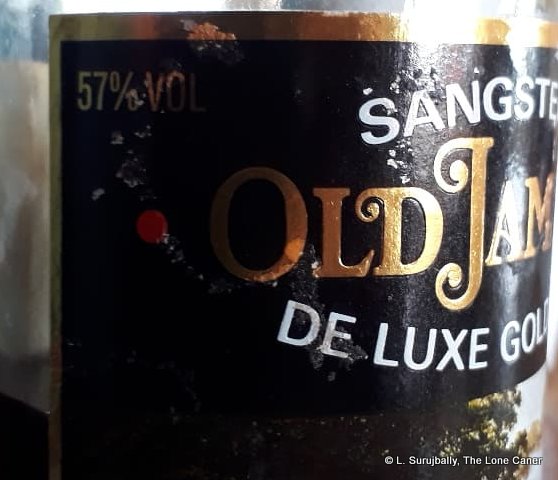

It is unknown from where he sourced his base stock. Given that this DeLuxe Gold rum was noted as comprising pot still distillate and being a blend, it could possibly be Hampden, Worthy Park or maybe even Appleton themselves or, from the profile, Longpond – or some combination, who knows? I think that it was likely between 2-5 years old, but that’s just a guess. References are slim at best, historical background almost nonexistent. The usual problem with these old rums. Note that after Dr. Sangster relocated to the Great Distillery in the Sky, his brand was acquired post-2001 by J. Wray & Nephew who do not use the name for anything except the rum liqueurs. The various blends have been discontinued.

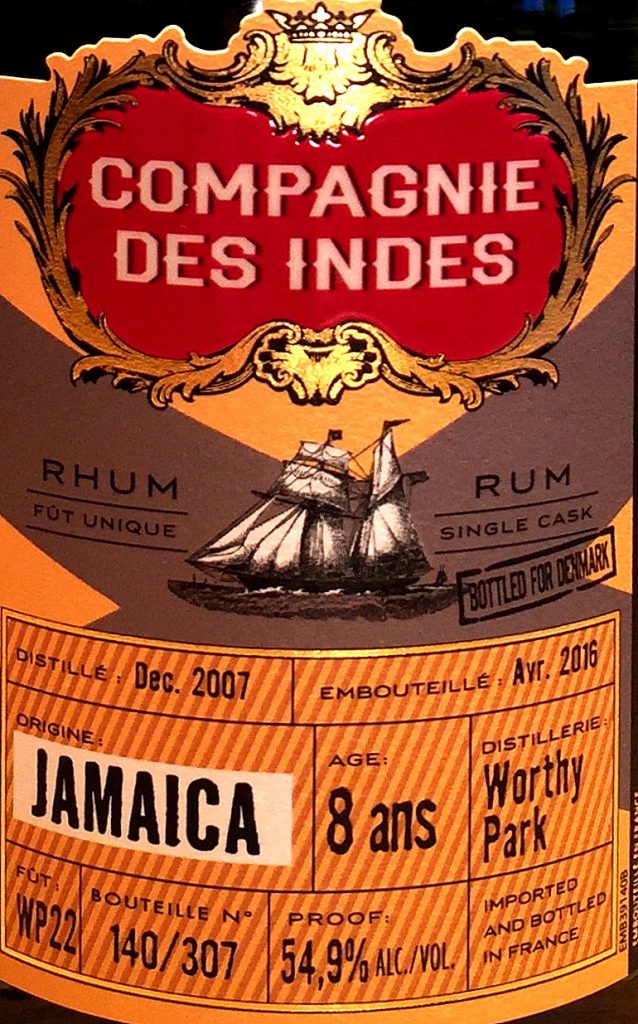

It is unknown from where he sourced his base stock. Given that this DeLuxe Gold rum was noted as comprising pot still distillate and being a blend, it could possibly be Hampden, Worthy Park or maybe even Appleton themselves or, from the profile, Longpond – or some combination, who knows? I think that it was likely between 2-5 years old, but that’s just a guess. References are slim at best, historical background almost nonexistent. The usual problem with these old rums. Note that after Dr. Sangster relocated to the Great Distillery in the Sky, his brand was acquired post-2001 by J. Wray & Nephew who do not use the name for anything except the rum liqueurs. The various blends have been discontinued. Nose – Opens with the scents of a midden heap and rotting bananas (which is not as bad as it sounds, believe me). Bad watermelons, the over-cloying reek of genteel corruption, like an unwashed rum strumpet covering it over with expensive perfume. Acetones, paint thinner, nail polish remover. That is definitely some pot still action. Apples, grapefruits, pineapples, very sharp and crisp. Overripe peaches in tinned syrup, yellow soft squishy mangoes. The amalgam of aromas doesn’t entirely work, and it’s not completely to my taste…but intriguing nevertheless It has a curious indeterminate nature to it, that makes it difficult to say whether it’s WP or Hampden or New Yarmouth or what have you.

Nose – Opens with the scents of a midden heap and rotting bananas (which is not as bad as it sounds, believe me). Bad watermelons, the over-cloying reek of genteel corruption, like an unwashed rum strumpet covering it over with expensive perfume. Acetones, paint thinner, nail polish remover. That is definitely some pot still action. Apples, grapefruits, pineapples, very sharp and crisp. Overripe peaches in tinned syrup, yellow soft squishy mangoes. The amalgam of aromas doesn’t entirely work, and it’s not completely to my taste…but intriguing nevertheless It has a curious indeterminate nature to it, that makes it difficult to say whether it’s WP or Hampden or New Yarmouth or what have you.  Finish – Shortish, dark off-fruits, vaguely sweet, briny, a few spices and musky earth tones.

Finish – Shortish, dark off-fruits, vaguely sweet, briny, a few spices and musky earth tones.

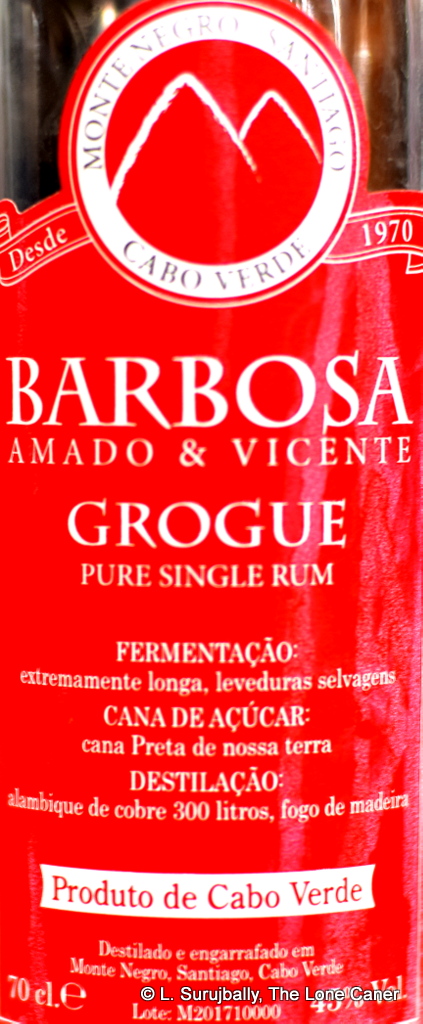

This was also the case when tasted. The bright and clean fruity-ester notes were more in evidence here than on the nose — green apples, sultanas, hard yellow mangoes, thyme, more pineapples, a bag of white guavas and watery pears. There was a hint of danger in the hint of cucumbers in white vinegar with a pimento or two floating around, but this never seriously came forward, a hint was all you got; and at best, with some concentration, there were some additional herbs (dill, cilantro), grass, sugar water and maybe a few more olives. I particularly liked the mild finish, by the way – clear and fruity and minty, with thyme, wet grass, and some almonds and white chocolate, sweet and unassuming, just right for what had come before.

This was also the case when tasted. The bright and clean fruity-ester notes were more in evidence here than on the nose — green apples, sultanas, hard yellow mangoes, thyme, more pineapples, a bag of white guavas and watery pears. There was a hint of danger in the hint of cucumbers in white vinegar with a pimento or two floating around, but this never seriously came forward, a hint was all you got; and at best, with some concentration, there were some additional herbs (dill, cilantro), grass, sugar water and maybe a few more olives. I particularly liked the mild finish, by the way – clear and fruity and minty, with thyme, wet grass, and some almonds and white chocolate, sweet and unassuming, just right for what had come before. Rumaniacs Review # 096 | 0617

Rumaniacs Review # 096 | 0617

So the search for more info begins. Now, if you’re looking on

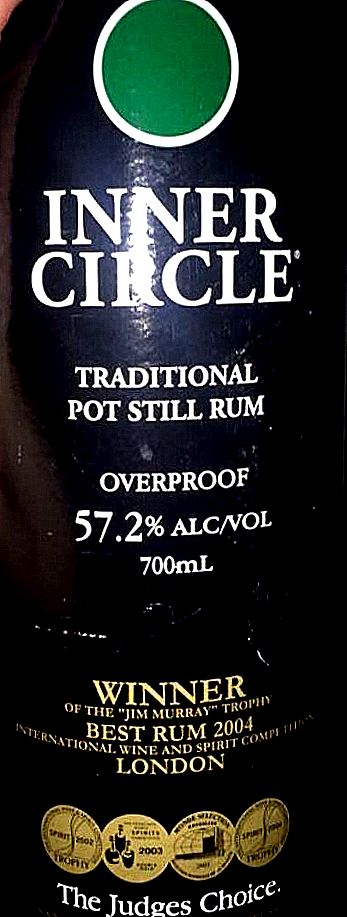

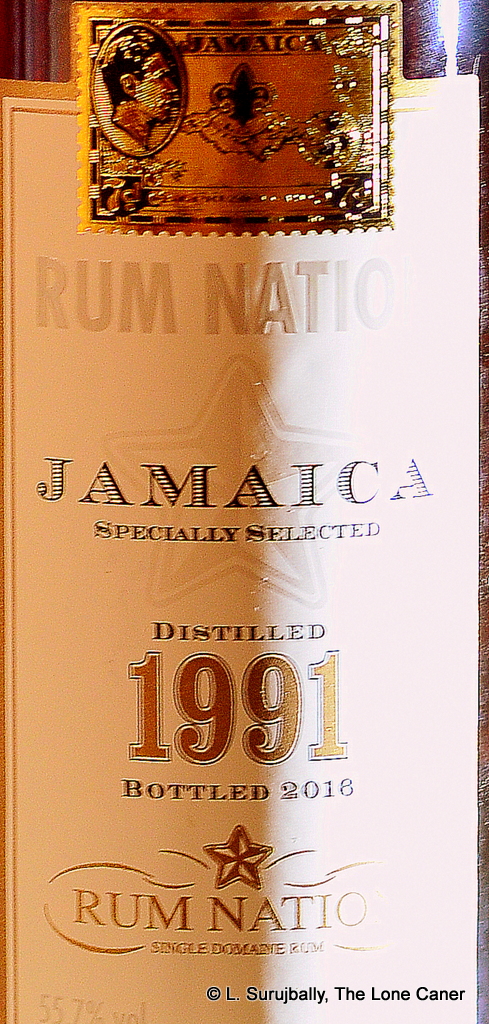

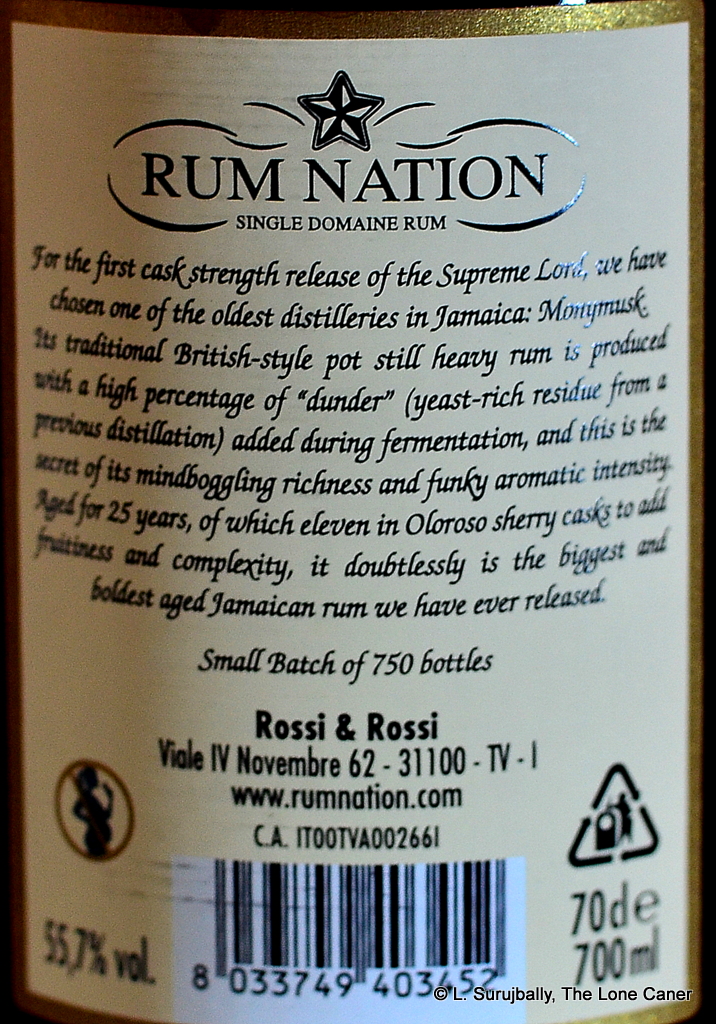

So the search for more info begins. Now, if you’re looking on  With respect to the palate, at 46%, much as I wish it were stronger, the rum is simply luscious, perhaps too much so – had it been sweeter (and it isn’t) it might have edged dangerously close to a cloying mishmash, but as it is, the cat’s-tongue-rough-and-smooth profile was excellent. It melded leather and the creaminess of salt butter and brie with licorice, brown sugar, molasses and butter cookies (as a hat tip to them barking-mad northern vikings, I’ll say were Danish). Other tastes emerge: prunes and dark fruit – lots of dark fruit. Blackberries, plums, dates. Very dense, layer upon layer of tastes that combined really really well, and providing a relatively gentle but tasteful summary on the finish. Sometimes things fall apart (or disappear entirely) at this stage, but here it’s like a never ending segue that reminds us of cedar, sawdust, sugar raisins, plums, prunes, and chocolate oranges.

With respect to the palate, at 46%, much as I wish it were stronger, the rum is simply luscious, perhaps too much so – had it been sweeter (and it isn’t) it might have edged dangerously close to a cloying mishmash, but as it is, the cat’s-tongue-rough-and-smooth profile was excellent. It melded leather and the creaminess of salt butter and brie with licorice, brown sugar, molasses and butter cookies (as a hat tip to them barking-mad northern vikings, I’ll say were Danish). Other tastes emerge: prunes and dark fruit – lots of dark fruit. Blackberries, plums, dates. Very dense, layer upon layer of tastes that combined really really well, and providing a relatively gentle but tasteful summary on the finish. Sometimes things fall apart (or disappear entirely) at this stage, but here it’s like a never ending segue that reminds us of cedar, sawdust, sugar raisins, plums, prunes, and chocolate oranges.

Until

Until

And for anyone who enjoys sipping rich Jamaicans that don’t stray too far into insanity (the

And for anyone who enjoys sipping rich Jamaicans that don’t stray too far into insanity (the  The rum continues along the path set by all the seven Supreme Lords that came before it, and since I’ve not tried them all, I can’t say whether others are better, or if this one eclipses the lot. What I do know is that they are among the best series of Jamaican rums released by any independent, among the oldest, and a key component of my own evolving rum education.

The rum continues along the path set by all the seven Supreme Lords that came before it, and since I’ve not tried them all, I can’t say whether others are better, or if this one eclipses the lot. What I do know is that they are among the best series of Jamaican rums released by any independent, among the oldest, and a key component of my own evolving rum education.

This brings us to the

This brings us to the  Just as we don’t see Americans making too many full proof rums, it’s also hard to see them making true agricoles, especially since the term is so tightly bound up with the spirits of the French islands.

Just as we don’t see Americans making too many full proof rums, it’s also hard to see them making true agricoles, especially since the term is so tightly bound up with the spirits of the French islands.

We don’t much associate the USA with cask strength rums, though of course they do exist, and the country has a long history with the spirit. These days, even allowing for a swelling wave of rum appreciation here and there, the US rum market seems to be primarily made up of low-end mass-market hooch from massive conglomerates at one end, and micro-distilleries of wildly varying output quality at the other. It’s the micros which interest me, because the US doesn’t do “independent bottlers” as such – they do this, and that makes things interesting, since one never knows what new and amazing juice may be lurking just around the corner, made with whatever bathtub-and-shower-nozzle-held-together-with-duct-tape distillery apparatus they’ve slapped together.

We don’t much associate the USA with cask strength rums, though of course they do exist, and the country has a long history with the spirit. These days, even allowing for a swelling wave of rum appreciation here and there, the US rum market seems to be primarily made up of low-end mass-market hooch from massive conglomerates at one end, and micro-distilleries of wildly varying output quality at the other. It’s the micros which interest me, because the US doesn’t do “independent bottlers” as such – they do this, and that makes things interesting, since one never knows what new and amazing juice may be lurking just around the corner, made with whatever bathtub-and-shower-nozzle-held-together-with-duct-tape distillery apparatus they’ve slapped together.