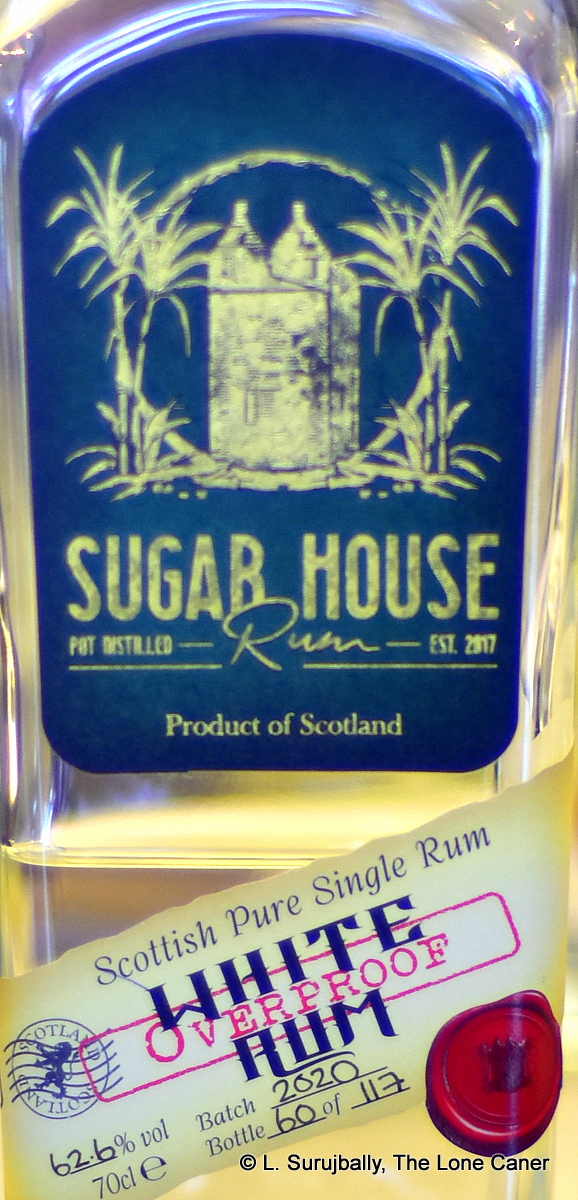

The last two reviews were of products from a Scottish rum maker called Sugar House, who bootstrapped a hybrid pot still, a batsh*t crazy production ethos and somehow came out with two unaged rums that should not have succeeded as well as they did…but did; and blew my socks off. This is what happens when a producer, no matter how small or how new, takes their rum seriously, really loves the subject, and isn’t averse to tinkering around a bit, dispenses with the training wheels, and simply blasts off. Juice like this is the high point of the reviewing game, where you see something original, something good, not terribly well known outside its place of origin, and aren’t afraid to champion it.

The last two reviews were of products from a Scottish rum maker called Sugar House, who bootstrapped a hybrid pot still, a batsh*t crazy production ethos and somehow came out with two unaged rums that should not have succeeded as well as they did…but did; and blew my socks off. This is what happens when a producer, no matter how small or how new, takes their rum seriously, really loves the subject, and isn’t averse to tinkering around a bit, dispenses with the training wheels, and simply blasts off. Juice like this is the high point of the reviewing game, where you see something original, something good, not terribly well known outside its place of origin, and aren’t afraid to champion it.

Consider then the polar opposite, the yin to Sugar House’s yang, a contrasting product which sports a faux-nautical title (we can be grateful that it omits any mentions or pictures of pirates), a strength of 40% and not a whole lot else. Merchant Shipping Co.’s branded product is in fact, a third party rum — “imported Caribbean white rum” — put together by Highwood Distillery in Alberta (in Canada), which is probably better known for the surprisingly robust Potter’s (gained when they bought out that lonely distillery from BC in 2005) and the eminently forgettable Momento, which may be the single most unread post on this entire site. Here they didn’t make the rum, but imported it, (the AGLC website suggests it’s probably from Guyana, which Highwood deals in for its own stable), and made it on contract for exclusive sale in Liquor Depot and Wine & Beyond stores in western Canada.

Let me spare you some reading: it’s barely worth sticking into a cocktail, and I wouldn’t stir it with the ferrule of my umbrella. Merchant Shipping white rum is a colourless spirit tucked into a cheap plastic bottle, sold for twenty five bucks, and somehow has the effrontery (please God, let it not be pride) to label itself as rum. I don’t really blame Highwood for this – it’s a contract rum after all – but I’m truly amazed that a liquor store as large and well stocked as Wine & Beyond could put their name behind abominable bottom feeder stuff like this.

Because it’s just so pointless. So completely unnecessary. It smells on first opening and resting and nosing, like mothballs left too long in an overstuffed and rarely-opened clothes closet, where everything is old, long-disused, and shedding. It smells like rubbing alcohol and faint gasoline, and my disbelieving notes right out of the gate ask “Wtf is this?? My grandmother’s arthritis cream?” It is a 40% spirit, but I swear to you there’s not much in here that says rum to anyone – it’s seems like denatured, filtered, diluted neutral spirit…that’s then dumbed down just in case somebody might mistake it for a real drink.

Because it’s just so pointless. So completely unnecessary. It smells on first opening and resting and nosing, like mothballs left too long in an overstuffed and rarely-opened clothes closet, where everything is old, long-disused, and shedding. It smells like rubbing alcohol and faint gasoline, and my disbelieving notes right out of the gate ask “Wtf is this?? My grandmother’s arthritis cream?” It is a 40% spirit, but I swear to you there’s not much in here that says rum to anyone – it’s seems like denatured, filtered, diluted neutral spirit…that’s then dumbed down just in case somebody might mistake it for a real drink.

The palate continues this disappointment (although I’m an optimist, and had hopes); it tastes thin and harsh, oily, medicinal, all of it faint and barely there – even for living room strength there’s little to write home about: a lingering unpleasant back-taste of sardines and olive oil, offset by a single overripe pear garnished with a sodden slice of watery melon and a squished banana, and if there is more I’d have to imagine it. Finish is gone so fast you’d think it was the road runner’s fumes, minus the comedy.

I can’t begin to tell you how this tasteless, useless, graceless, hopeless, classless, legless rum annoys me. Everything that could have given the spirit real character has been stripped away and left for dead. I said it was unnecessary and meant it: because you could pour the whole bottle down the drain and go to sleep knowing you’d never missed a thing — yet it’s made, it’s on shelves, it sells, and a whole generation of young Canadians who can afford nothing else will go to their graves thinking this is what rum is and avoid it forever after. That’s what the implication of this thing is, and that’s the one thing it’s good at.

(#979)(65/100) ⭐½

Opinion

It gives me no pleasure to write reviews that slam a homegrown product — because homegrown products are what give a country or an island or a territory or an acreage its unique selling point, its mental and physical terroire. That’s what’s wrong with this faux, ersatz “Caribbean” rum, because there’s absolutely nothing that says Canada here at all (let alone rum, and certainly not the Caribbean) and as noted above, it’s an import (a near neutral spirit import at that, apparently).

Yet, as I’ve tried to make clear, one of those areas where there is serious potential for putting one’s country on the map lies in rums that don’t go for the least common denominator, don’t go for the mass-market miscellaneous dronish supermarket shelves, and certainly don’t go for the profit-maximizing-at-all-costs uber-capitalist ethos of the provincial liquor monopolies who could give a damn about terroire or real taste chops. It’s the blinkered mentality of them and the stores who follow it that allows rum like this to be made, as if the French rhum makers, global cane juice distillers, and the UK New Wave haven’t shown us, time and again, that better could be done, has been done…and indeed, should be done.

Other notes

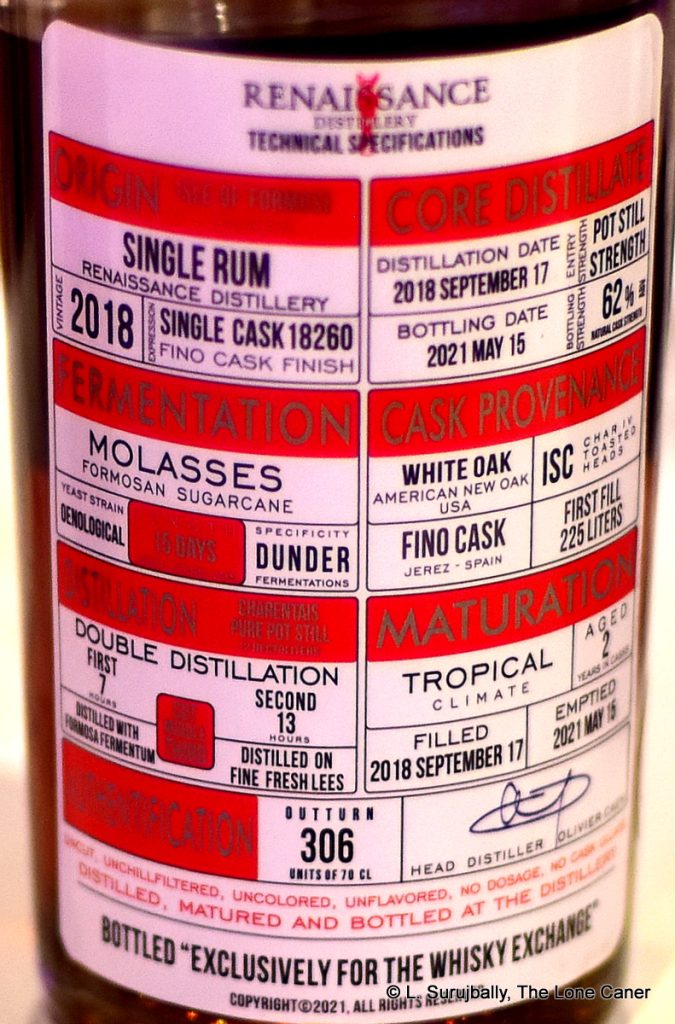

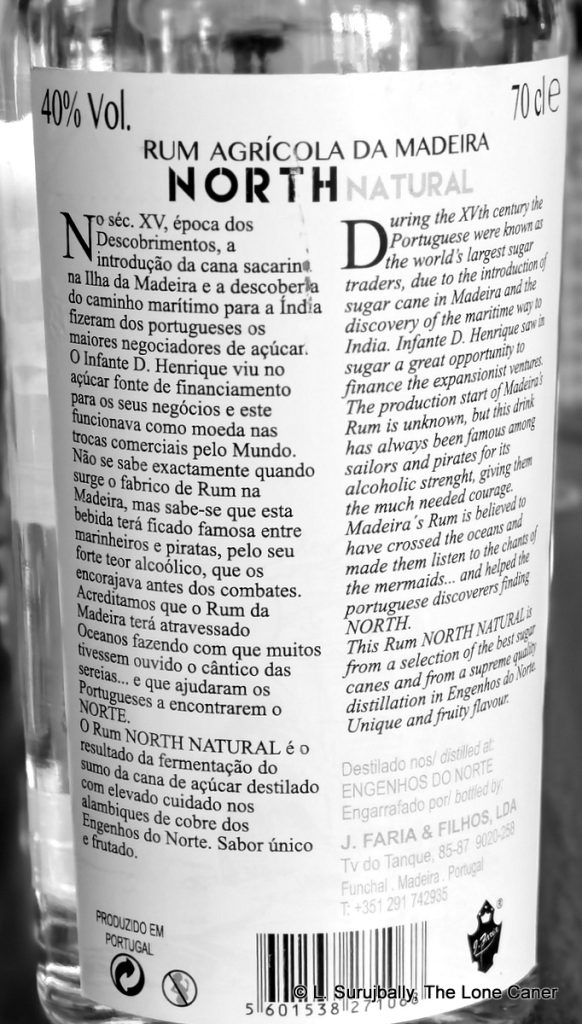

- There’s no tech sheet to go with the rum and nothing on the label, but I think it’s fair to say no self-respecting pot still ever made a rum like this, so, column still. Also, molassess based. It is probably aged a bit and then filtered, and my guess is less than a year.

- Five minute video summary is here