Recently I was observed to be writing more reviews of obscure rums nobody ever hears about (or can get) than the commonly favoured tipple and new releases favoured by the commenterati. That’s a completely fair thing to say, because I do. Not because I want to be behind the times — I’m gutted I couldn’t try the three new pot-still Appletons from Velier so many people are waxing rhapsodical about, for example — it’s more a factor of my current location, and inability to travel and the cancellation of the entire 2020 rumfest season.

It’s also as a somewhat deliberate choice. After all, there are loads of people rendering opinions on what’s out there that’s and new and interesting, so what more could one blogger really add? And so I take advantage of these admittedly peculiar circumstances to write about rums that are less well known, a bit off the beaten track, but no less fascinating. Because there will always be, one day, years from now, questions about such bottles — even if only by a single individual finding a dust-covered specimen on some back shelf someplace, written off by the store or owner, ignored by everyone else.

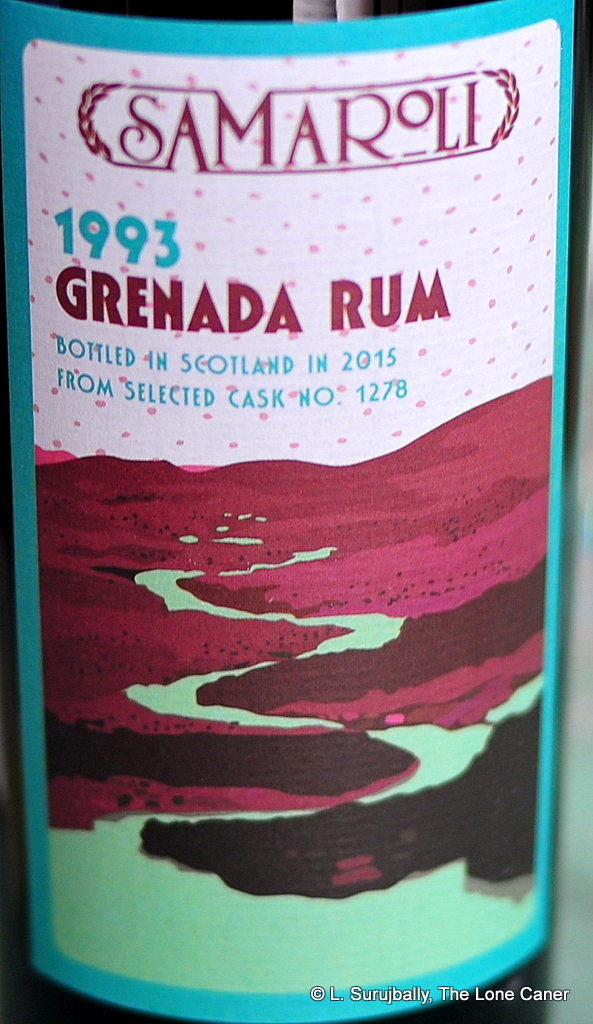

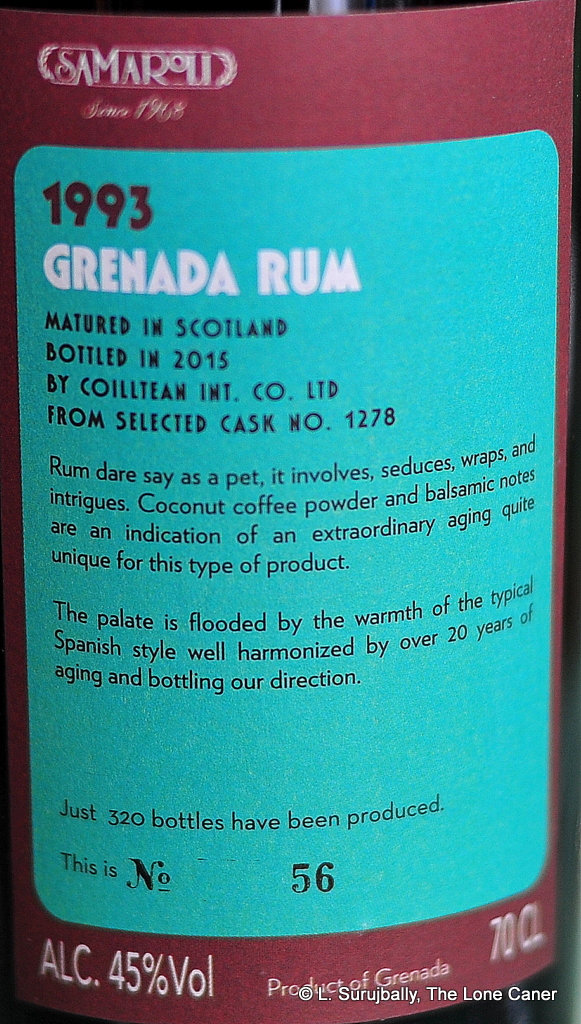

One such is this Samaroli rum sporting an impressive 22 years of continental ageing, hailing from Grenada – alas, not Rivers Antoine, but you can’t have everything (the rum very likely came from Westerhall – they ceased distilling in 1996 but were the only ones exporting bulk rum before that). You’ll look long and hard before you find any kind of write up about it, or anyone who owns it – not surprising when you consider the €340 price tag it fetches in stores and at auction. This is the second Grenada rum selected under the management of Antonio Bleve who took over operations at Samaroli in the mid 2000s and earned himself a similar reputation as Sylvio Samaroli (RIP), that of having the knack of picking right.

One such is this Samaroli rum sporting an impressive 22 years of continental ageing, hailing from Grenada – alas, not Rivers Antoine, but you can’t have everything (the rum very likely came from Westerhall – they ceased distilling in 1996 but were the only ones exporting bulk rum before that). You’ll look long and hard before you find any kind of write up about it, or anyone who owns it – not surprising when you consider the €340 price tag it fetches in stores and at auction. This is the second Grenada rum selected under the management of Antonio Bleve who took over operations at Samaroli in the mid 2000s and earned himself a similar reputation as Sylvio Samaroli (RIP), that of having the knack of picking right.

I would not suggest, however, that this is entirely the case here. The rum noses decently enough (it clocks in at 45% ABV) and smells pungently sweet, akin to a smoked-out beehive dripping honey into the ashes. There’s caramel toffee, bon bons, cinnamon, white chocolate and a kind of duskiness to the aroma that isn’t bad. After some time additional smells of vanilla and salted caramel ice cream can be detected, but on the whole it’s not very heavy in the fruits department. Some plums and dark berries, and a bare minimum of the tart notes of sharper fruit to balance them off.

The palate is, frankly, something of a disappointment after a nose that was already not all that exciting to begin with. Many of the notes that are present when I smell it return for a subtler encore when sampled: salted caramel ice cream, a dulce de leche coffee, more white chocolate with some nuttiness, honey, caramel, cinnamon, and very few crisp fruits that would have livened up the experience some. Raisins, dates, dried plums is more or less it and I really have no idea what the back label is on about when it refers to “typical Spanish style.” The finish is similarly middle of the road, as if fearing to offend, and gives up a few final notes of cinnamon, chocolate, raisins, plums and toffee, dusted with a bit of vanilla, and that’s about all you’re getting.

So what to make of this expensive two-decades-old Grenada rum released by an old and proud Italian house? Overall it’s really quite pleasant, avoids disaster and is tasty enough, just nothing special. I was expecting more. You’d be hard pressed to identify its provenance if tried blind. Like an SUV taking the highway, it stays firmly on the road without going anywhere rocky or offroad, perhaps fearing to nick the paint or muddy the tyres.

So what to make of this expensive two-decades-old Grenada rum released by an old and proud Italian house? Overall it’s really quite pleasant, avoids disaster and is tasty enough, just nothing special. I was expecting more. You’d be hard pressed to identify its provenance if tried blind. Like an SUV taking the highway, it stays firmly on the road without going anywhere rocky or offroad, perhaps fearing to nick the paint or muddy the tyres.

The problem with that kind of undistinguished anonymity which takes no chances, is that it provides the drinker with no new discoveries, no new challenges, nothing to write home in shock and awe about. To some extent, I’d suggest the rum is a product of its time – in 2005, IBs were still much more cautious about releasing cask-strength, hairy-chested beefcakes that reordered the rumiverse, and were careful not too stray too far from the easy blends which was what sold big time back then. That’s all well and good, but it also shows that those who don’t dare, don’t win … and that’s why this rum is all but forgotten and unacknowledged now (unlike, of course, the Veliers from the same era). In short, it lacks distinctiveness and character, and remains merely a good way to drop two hundred quid without getting much of anything in return.

(#778)(80/100)

Other Notes

- 320 bottles of the 0.7 liter edition appeared….and another 120 bottles of a 0.5 liter edition

- The first Grenada rum selected by Bleve was the 1993-2011 45% with a blue label.

All that comes together in a rhum of uncommonly original aroma and taste. It opens with smells that confirm its provenance as an agricole, and it displays most of the hallmarks of a rhum from the blanc side (herbs, grassiness, crisp citrus and tart fruits)…but that out of the way, evidently feels it is perfectly within its rights to take a screeching ninety degree left turn into the woods. Woody and even meaty notes creep out, which seem completely out of place, yet somehow work. This all combines with salt, rancio, brine, and olives to mix it up some more, but the overall effect is not unpleasant – rather it provides a symphony of undulating aromas that move in and out, no single one ever dominating for long before being elbowed out of the way by another.

All that comes together in a rhum of uncommonly original aroma and taste. It opens with smells that confirm its provenance as an agricole, and it displays most of the hallmarks of a rhum from the blanc side (herbs, grassiness, crisp citrus and tart fruits)…but that out of the way, evidently feels it is perfectly within its rights to take a screeching ninety degree left turn into the woods. Woody and even meaty notes creep out, which seem completely out of place, yet somehow work. This all combines with salt, rancio, brine, and olives to mix it up some more, but the overall effect is not unpleasant – rather it provides a symphony of undulating aromas that move in and out, no single one ever dominating for long before being elbowed out of the way by another.

So let’s try it and see what the fuss is all about. Nose first. Well, it’s powerul sharp, let me tell you (63.8% ABV!), both crisper and more precise than the

So let’s try it and see what the fuss is all about. Nose first. Well, it’s powerul sharp, let me tell you (63.8% ABV!), both crisper and more precise than the

I was really and pleasantly surprised by how well it presented, to be honest. For a standard strength rhum, I expected less, but its complexity and changing character eventually won me over. Looking at others’ reviews of rhums in Reimonenq’s range I see similar flip flops of opinion running through them all. Some like one or two, some like that one more than that other one, there are those that are too dry, too sweet, too fruity (with a huge swing of opinion), and the little literature available is a mess of ups and downs.

I was really and pleasantly surprised by how well it presented, to be honest. For a standard strength rhum, I expected less, but its complexity and changing character eventually won me over. Looking at others’ reviews of rhums in Reimonenq’s range I see similar flip flops of opinion running through them all. Some like one or two, some like that one more than that other one, there are those that are too dry, too sweet, too fruity (with a huge swing of opinion), and the little literature available is a mess of ups and downs.

Rum Nation’s own

Rum Nation’s own

Colour – Gold brown

Colour – Gold brown

Savanna’s 2005 Cuvée Maison Blanche 10 Year Old rum, in production since 2008 is a companion to the 2005 10 YO Traditionnel and a somewhat lesser version of the superb

Savanna’s 2005 Cuvée Maison Blanche 10 Year Old rum, in production since 2008 is a companion to the 2005 10 YO Traditionnel and a somewhat lesser version of the superb

The word “Lontan” is difficult to pin down – in Haitian Creole, it means “long” and “long ago” while in old French it was “lointain” and meant “distant” and “far off”, and neither explains why Savanna picked it (though many establishments around the island use it in their names as well, so perhaps it’s an analogue to the english “Ye Olde…”). Anyway, aside from the traditional, creol, Intense and Metis ranges of rums (to which have now been added several others) there is this Lontan series – these are all variations of Grand Arôme rums, finished or not, aged or not, full-proof or not, which are distinguished by a longer fermentation period and a higher ester count than usual, making them enormously flavourful.

The word “Lontan” is difficult to pin down – in Haitian Creole, it means “long” and “long ago” while in old French it was “lointain” and meant “distant” and “far off”, and neither explains why Savanna picked it (though many establishments around the island use it in their names as well, so perhaps it’s an analogue to the english “Ye Olde…”). Anyway, aside from the traditional, creol, Intense and Metis ranges of rums (to which have now been added several others) there is this Lontan series – these are all variations of Grand Arôme rums, finished or not, aged or not, full-proof or not, which are distinguished by a longer fermentation period and a higher ester count than usual, making them enormously flavourful.

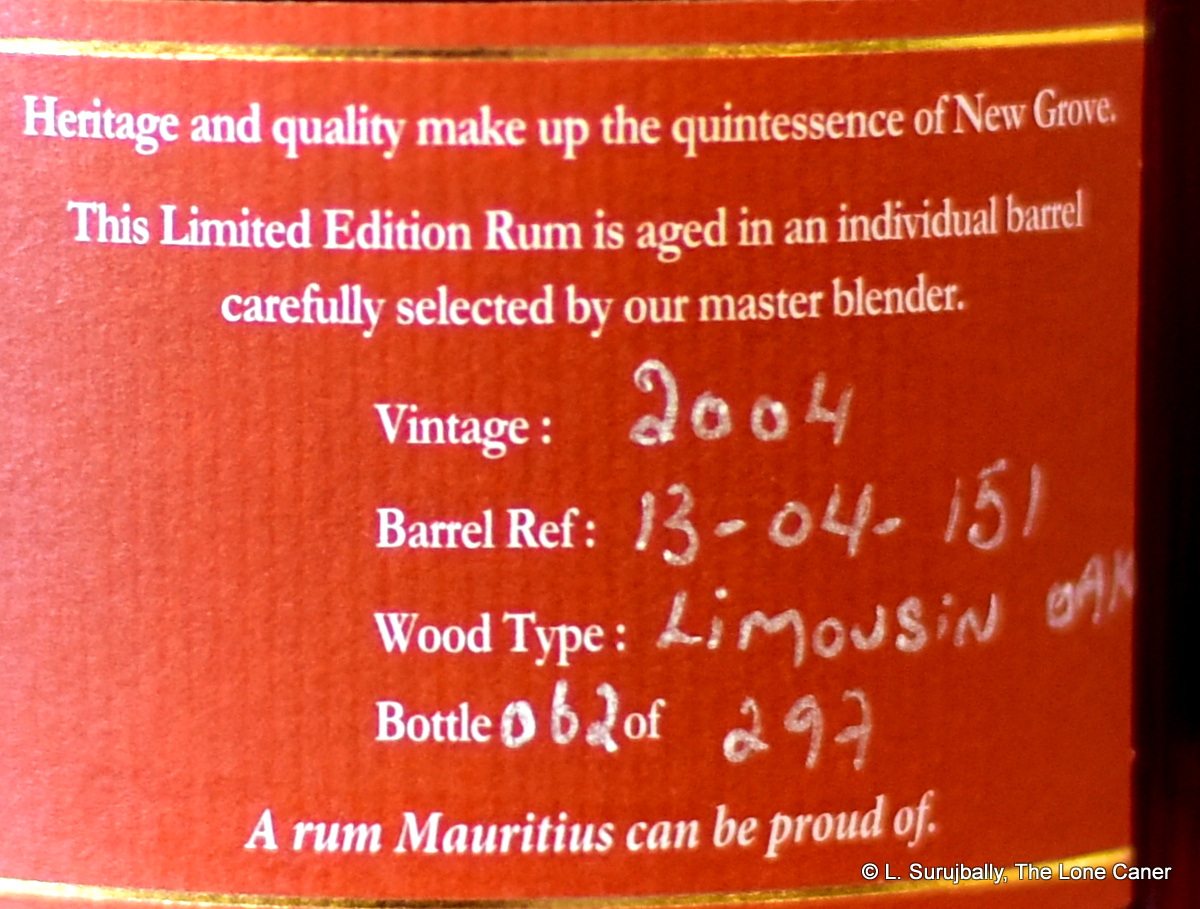

Although cold stats alone don’t tell the tale, I must confess to being intrigued, since a primary producer’s limited single-barrel expressions tend to be somewhat special, something they picked out for good reason. That felt like the case here – the initial smell was delicious, of burnt oranges and whipped cream (!!), a sort of liquid meringue pie if you will. It negotiated the twists and turns of tart and mellower aromas really well: honey, fruits, raisins, green apples, grapes,and ripe peaches. There was never too much of one or the other, and it was all quite civilized, soft and even warm

Although cold stats alone don’t tell the tale, I must confess to being intrigued, since a primary producer’s limited single-barrel expressions tend to be somewhat special, something they picked out for good reason. That felt like the case here – the initial smell was delicious, of burnt oranges and whipped cream (!!), a sort of liquid meringue pie if you will. It negotiated the twists and turns of tart and mellower aromas really well: honey, fruits, raisins, green apples, grapes,and ripe peaches. There was never too much of one or the other, and it was all quite civilized, soft and even warm Background history

Background history

As for the taste when sipped, “uninspiring” might be the kindest word to apply. It’s so light as to be nonexistent, and just seemed so…

As for the taste when sipped, “uninspiring” might be the kindest word to apply. It’s so light as to be nonexistent, and just seemed so…

This makes it a spiced or flavoured rum, and it’s at pains to demonstrate that: the extras added to the rum make themselves felt right from the beginning. The thin and vapid nose stinks of vanilla, so much so that the bit of mint, sugar water and light florals and fruits (the only things that can be picked out from underneath that nasal blanket), easily gets batted aside (and that’s saying something for a rum bottled at 40%). It’s a delicate, weak little sniff, without much going on. Except of course for vanilla.

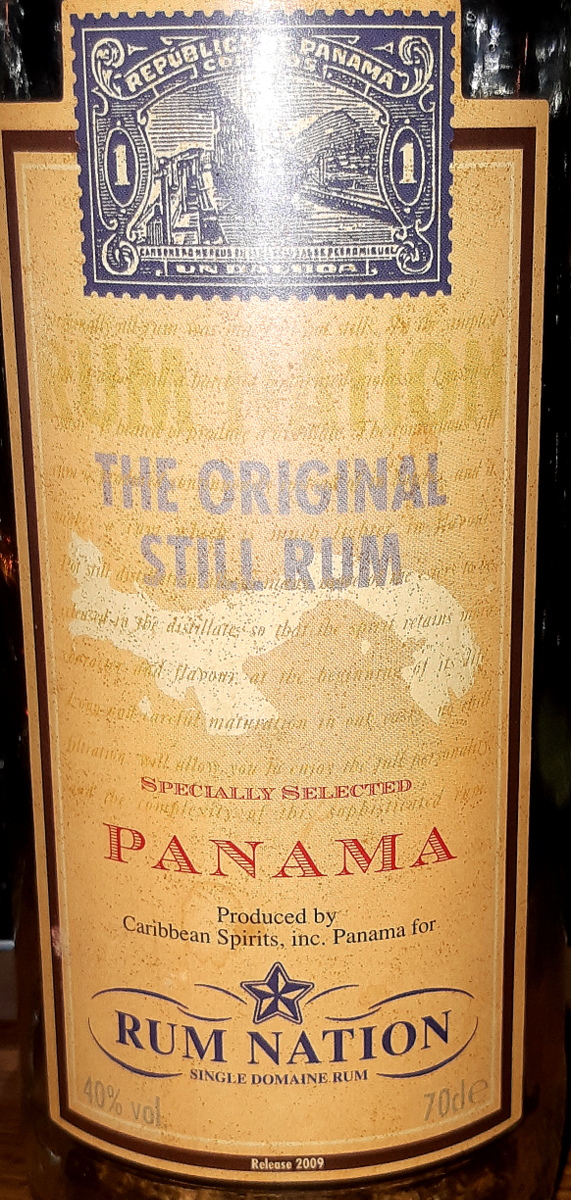

This makes it a spiced or flavoured rum, and it’s at pains to demonstrate that: the extras added to the rum make themselves felt right from the beginning. The thin and vapid nose stinks of vanilla, so much so that the bit of mint, sugar water and light florals and fruits (the only things that can be picked out from underneath that nasal blanket), easily gets batted aside (and that’s saying something for a rum bottled at 40%). It’s a delicate, weak little sniff, without much going on. Except of course for vanilla. The Rum Nation Panama 2009 edition exists in a peculiar place of my mind, since it’s the unavailable, long-gone predecessor of the

The Rum Nation Panama 2009 edition exists in a peculiar place of my mind, since it’s the unavailable, long-gone predecessor of the  That was the smell, but what did it taste like? Eighteen years in a barrel must, after all, show its traces. To some extent, yes: again,

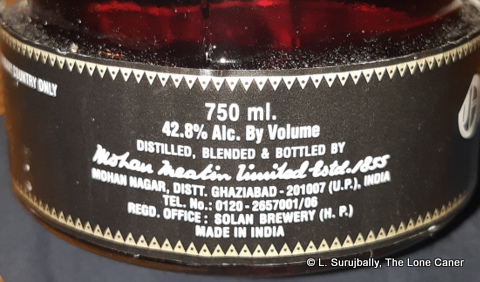

That was the smell, but what did it taste like? Eighteen years in a barrel must, after all, show its traces. To some extent, yes: again,  The Old Monk series of rums, perhaps among the best known to the Western world of those hailing from India, excites a raft of passionate posts whenever it comes up for mention, ranging from enthusiastic fanboy positivity, to disdain spread equally between its lack of disclosure about provenance and make, and the rather unique taste. Neither really holds water, but it is emblematic of both the unstinting praise of adherents who “just like rum” without thinking further, and those who take no cognizance of cultures other than their own and the different tastes that attend to them.

The Old Monk series of rums, perhaps among the best known to the Western world of those hailing from India, excites a raft of passionate posts whenever it comes up for mention, ranging from enthusiastic fanboy positivity, to disdain spread equally between its lack of disclosure about provenance and make, and the rather unique taste. Neither really holds water, but it is emblematic of both the unstinting praise of adherents who “just like rum” without thinking further, and those who take no cognizance of cultures other than their own and the different tastes that attend to them.

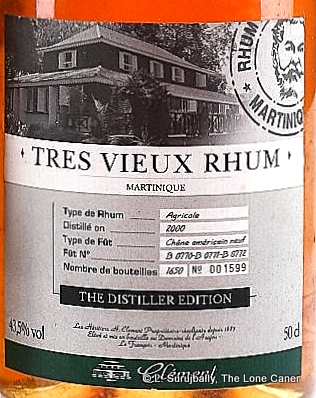

Nose – Doesn’t lend itself to quick identification at all. It’s of course pre-AOC so who knows what made it up, and the blend is not disclosed, alas. So, it’s thick, fruity and has that taste of a dry dark-red wine. Some fruits – raisins and prunes and blackberries – brown sugar, molasses, caramel, and a sort of sly, subtle reek of gaminess winds its way around the back end. Which is intriguing but not entirely supportive of the other aspects of the smell.

Nose – Doesn’t lend itself to quick identification at all. It’s of course pre-AOC so who knows what made it up, and the blend is not disclosed, alas. So, it’s thick, fruity and has that taste of a dry dark-red wine. Some fruits – raisins and prunes and blackberries – brown sugar, molasses, caramel, and a sort of sly, subtle reek of gaminess winds its way around the back end. Which is intriguing but not entirely supportive of the other aspects of the smell.

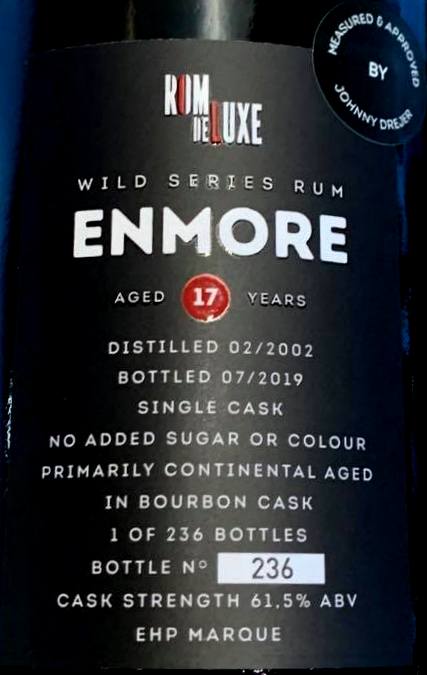

Things calmed down when Johnny Drejer approached, though, because in his fist he carried a bottle a lot of us hadn’t seen yet – the second in Romdeluxe’s “Wild Series” of rums, the Guyanese Enmore, with a black and white photo of a Jaguar glaring fiercely out. This was a 61.5% rum, 17 years old (2002 vintage, I believe), from one of the wooden stills (guess which?) — it had not formally gone on sale yet, and he had been presented with it for his 65th birthday a few days before (yeah, he looks awesome for his age). Since we already knew of the elephantine proportions of the

Things calmed down when Johnny Drejer approached, though, because in his fist he carried a bottle a lot of us hadn’t seen yet – the second in Romdeluxe’s “Wild Series” of rums, the Guyanese Enmore, with a black and white photo of a Jaguar glaring fiercely out. This was a 61.5% rum, 17 years old (2002 vintage, I believe), from one of the wooden stills (guess which?) — it had not formally gone on sale yet, and he had been presented with it for his 65th birthday a few days before (yeah, he looks awesome for his age). Since we already knew of the elephantine proportions of the  So far there is a tiger (R1 Hampden, Jamaica), jaguar (R2 Enmore, Guyana), puma (R3 Panama), black panther (R4 Belize), lion (R5, Bellevue, Guadeloupe) and leopard (R6 Caroni, Trinidad). I don’t know whether the photos are commissioned or from a stock library – what I do know is they are very striking, and you won’t be passing these on a shelf any time you see one. The stats on some of these rums are also quite impressive – take, for example, the strength of the Wild Tiger (85.2% ABV), or the age of the Wild Lion (25 years). These guys clearly aren’t messing around and understand you have to stand out from an ever more crowd gathering of indies these days, if you want to make a sale.

So far there is a tiger (R1 Hampden, Jamaica), jaguar (R2 Enmore, Guyana), puma (R3 Panama), black panther (R4 Belize), lion (R5, Bellevue, Guadeloupe) and leopard (R6 Caroni, Trinidad). I don’t know whether the photos are commissioned or from a stock library – what I do know is they are very striking, and you won’t be passing these on a shelf any time you see one. The stats on some of these rums are also quite impressive – take, for example, the strength of the Wild Tiger (85.2% ABV), or the age of the Wild Lion (25 years). These guys clearly aren’t messing around and understand you have to stand out from an ever more crowd gathering of indies these days, if you want to make a sale.

The palate was about par for the course for a rum bottled at this strength. Initially it felt like it was weak and not enough was going on (as if the profile should have emerged on some kind of schedule), but it was just a slow starter: it gets going with citrus, vanilla, flowers, a lemon meringue pie, plums and blackberry jam. This faded out and is replaced by sugar cane sap, swank and the grassy vegetal notes mixed up with ashes (!!) and burnt sugar. Out of curiosity I added some water , and was rewarded with citrus, lemon-ginger tea, the tartness of ripe gooseberries, pimentos and spanish olives. It took concentration and time to tease them out, but they were, once discerned, quite precise and clear. Still, strong they weren’t (“forceful” would not be an adjective used to describe it) and as expected the finish was easygoing, a bit crisp, with light fruit, fleshy and sweet and juicy, quite ripe, not so much citrus this time. The grassy and herbal notes are very much absent by this stage, replaced by a woody and spicy backnote, medium long and warm

The palate was about par for the course for a rum bottled at this strength. Initially it felt like it was weak and not enough was going on (as if the profile should have emerged on some kind of schedule), but it was just a slow starter: it gets going with citrus, vanilla, flowers, a lemon meringue pie, plums and blackberry jam. This faded out and is replaced by sugar cane sap, swank and the grassy vegetal notes mixed up with ashes (!!) and burnt sugar. Out of curiosity I added some water , and was rewarded with citrus, lemon-ginger tea, the tartness of ripe gooseberries, pimentos and spanish olives. It took concentration and time to tease them out, but they were, once discerned, quite precise and clear. Still, strong they weren’t (“forceful” would not be an adjective used to describe it) and as expected the finish was easygoing, a bit crisp, with light fruit, fleshy and sweet and juicy, quite ripe, not so much citrus this time. The grassy and herbal notes are very much absent by this stage, replaced by a woody and spicy backnote, medium long and warm

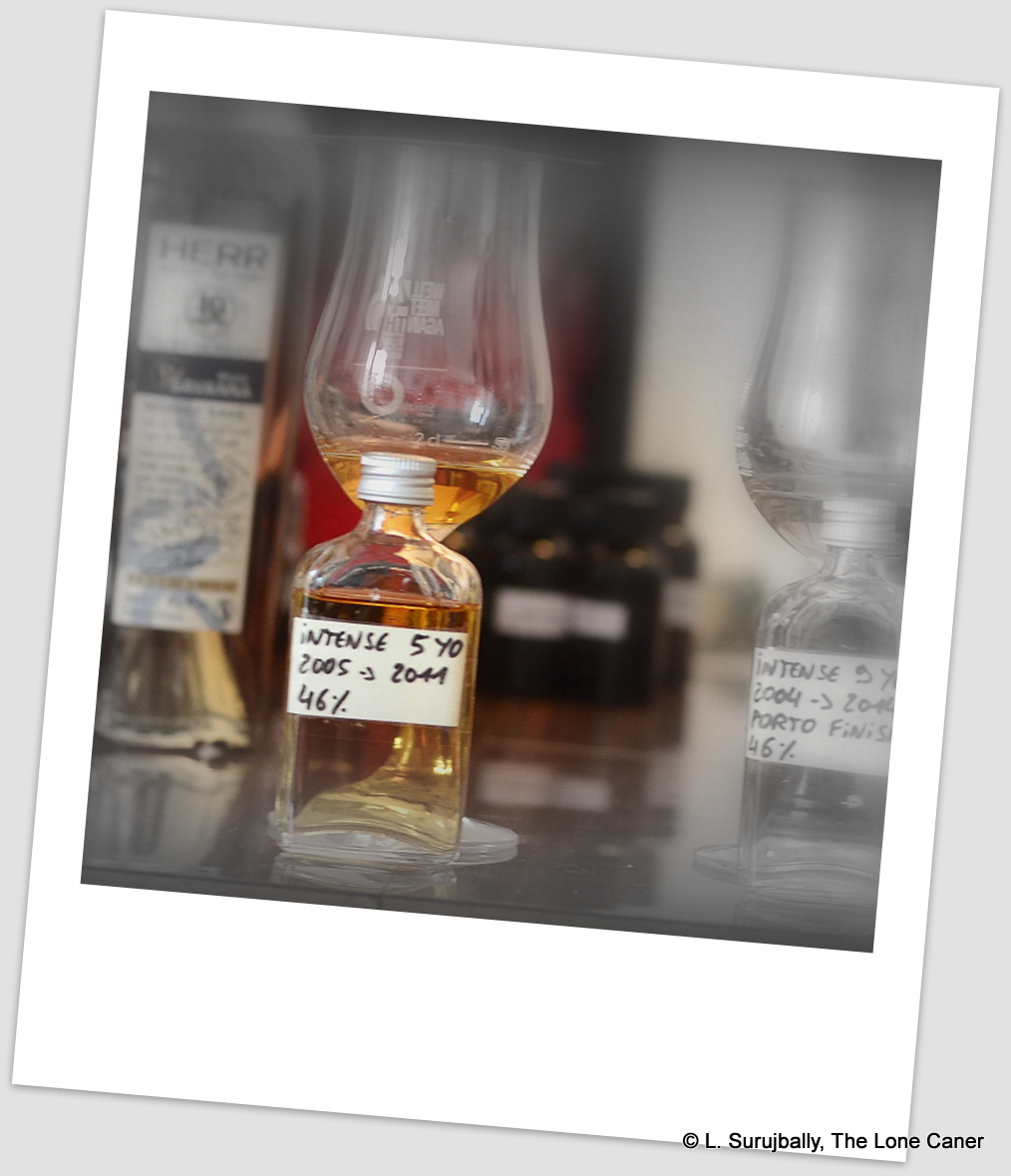

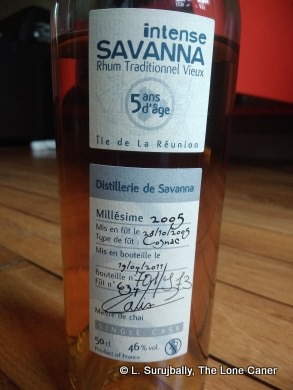

The youth is sensed upon sipping, and it’s an interesting if delicate amalgam. It presents as sharp to begin with, yet the bite climbs back down to gentle very quickly. Some bitter tannins, dampened down before they get a chance to descend into obnoxiousness. Citrus, oranges, nuts, plums, very tart, a bit thin overall to taste…not spotting too much cognac here. Strawberries and pineapples, weak. Nose was better, if not strictly comparable but then, I wasn’t drinking it through my schnozz either. Anyway, good tastes, a little thin, leading to a brisk finish, on the weak side of firm, gone quickly. Tart gooseberries, turmeric, strawberries, some citrus, and a last touch of that honey I enjoyed…it was a nice closing touch.

The youth is sensed upon sipping, and it’s an interesting if delicate amalgam. It presents as sharp to begin with, yet the bite climbs back down to gentle very quickly. Some bitter tannins, dampened down before they get a chance to descend into obnoxiousness. Citrus, oranges, nuts, plums, very tart, a bit thin overall to taste…not spotting too much cognac here. Strawberries and pineapples, weak. Nose was better, if not strictly comparable but then, I wasn’t drinking it through my schnozz either. Anyway, good tastes, a little thin, leading to a brisk finish, on the weak side of firm, gone quickly. Tart gooseberries, turmeric, strawberries, some citrus, and a last touch of that honey I enjoyed…it was a nice closing touch.