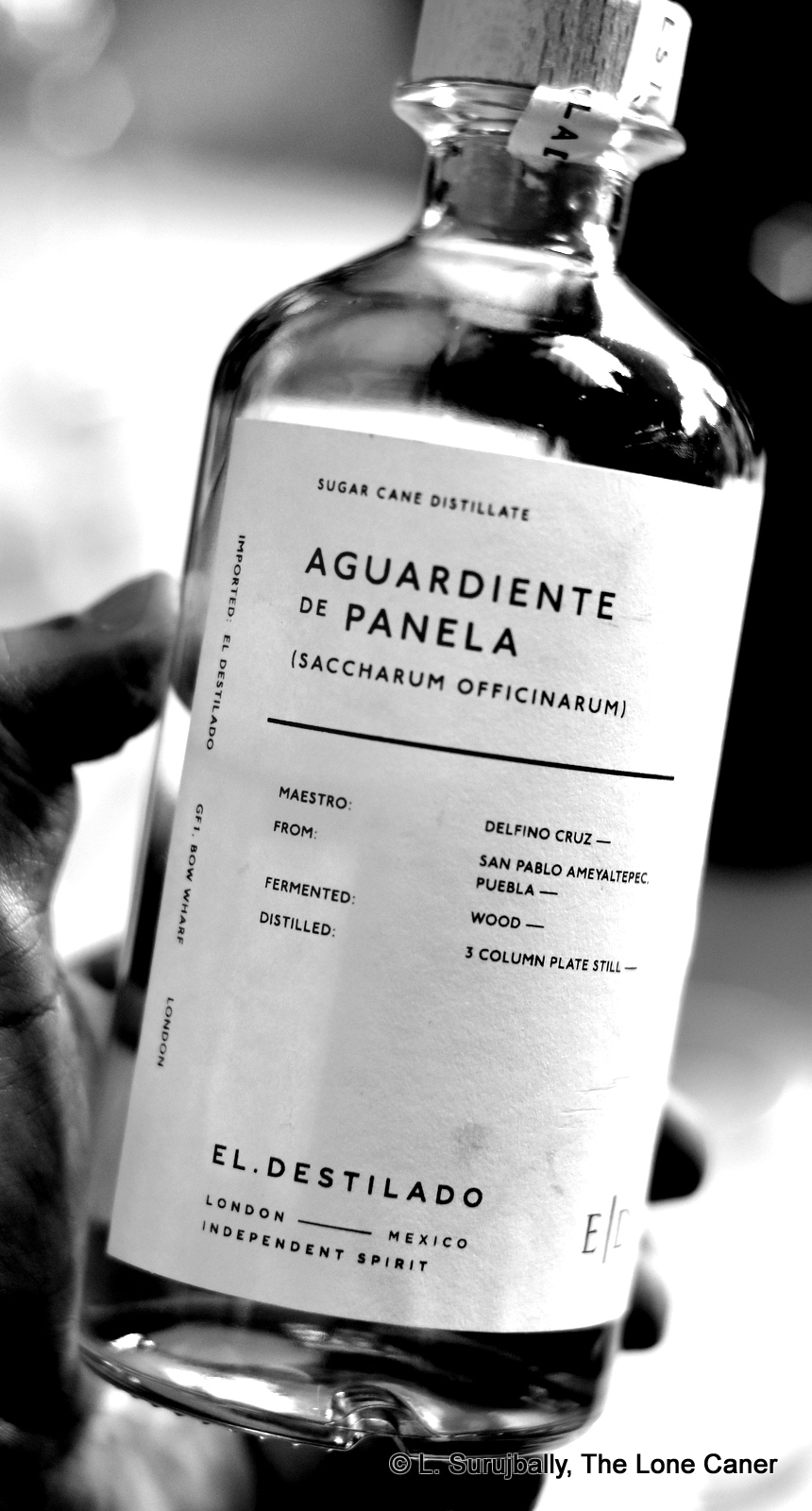

It was probably a good thing that I first tried this innocent looking white rum released by the UK independent bottler El Destilado (not to be confused with the restaurant of the same name in Oaxaca) without knowing much about it. It came in a smallish bottle, sporting a starkly simple label I didn’t initially peruse too closely, and since I was at a rumfest, and it had been handed to me by a rum chum, well, what else could it be, right?

It might have been a rum, but even at the supposedly standard strength of 43.15% ABV, the juice burst with flavours that instantly recalled indigenous unaged cane juice like clairin, or a supercharged grogue fresh of the still and sporting serious attitude. It smelled, first of all, woody — resinous, musty, oily, lemony; it reeked of brine and olives, almonds, pine-sol air freshener and only at the back end, after taking some time to recover, were there a few shy hints of flowers and some rich, almost-gone fleshy fruits. That’s not much when you think about it, but I assure you, it made up in intensity what it lacked in complexity.

Okay, so this was different, I thought and tasted it. It was solid and serious, completely dense with all sorts of interesting flavours: first off, very pine-y and smokey. More pine sol — did someone mix this with household disinfectant or something? This was followed by fresh damp sawdust of sawn lumber made into furniture right way and then polished with too much varnish, right in the sawmill (!!). Vegetable soup heavy on the salt, with generous doses of black pepper and garlic and cilantro…and more pine. Barbeque sauce and smoky sweet spices, like hickory I guess. Darkly sweet but not precisely fruity – though there are some of those – more like the heavy pungency of rotting oranges on a midden heap somewhere hot and tropical, closed off by a long and smoky finish redolent of lemon pine scent, and spoiling fruits, and more olives.

Okay, so this was different, I thought and tasted it. It was solid and serious, completely dense with all sorts of interesting flavours: first off, very pine-y and smokey. More pine sol — did someone mix this with household disinfectant or something? This was followed by fresh damp sawdust of sawn lumber made into furniture right way and then polished with too much varnish, right in the sawmill (!!). Vegetable soup heavy on the salt, with generous doses of black pepper and garlic and cilantro…and more pine. Barbeque sauce and smoky sweet spices, like hickory I guess. Darkly sweet but not precisely fruity – though there are some of those – more like the heavy pungency of rotting oranges on a midden heap somewhere hot and tropical, closed off by a long and smoky finish redolent of lemon pine scent, and spoiling fruits, and more olives.

This was intense. Too raw and uncultured to be a serious top ender, white or otherwise — and I like white rums, as you know — but defiantly original and really quite unique. I thought the pine notes were overbearing and spoiled the experience somewhat…other than that, a completely solid rum that was probably cane juice, and probably unaged, and a cousin to the French island agricoles. Somewhere out there a bartender was loving this thing and blowing it kisses.

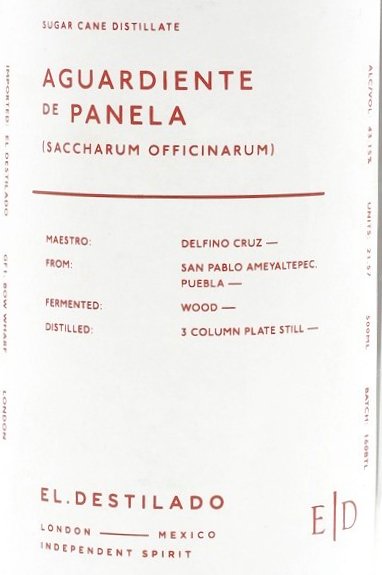

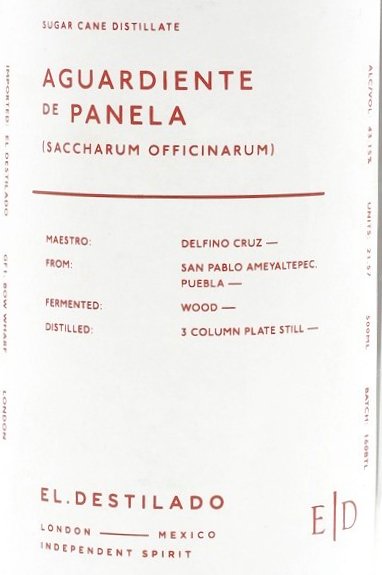

Which was correct, as confirmed by a more detailed look at that label. It was an unaged cane juice spirit called Aguardiente de Panela, came from Mexico, was akin to the Paranubes from Oaxaca and many others like it. I cautiously liked it – “appreciated” might be a better term; it was tasty, quite original, and felt like it took rum in whole new directions, though it took care not to call itself that. I can say with some assurance that you would be unlikely to have tried anything like it before and therein might lie both its attraction and downfall. But I suggest that if you can, try it. It might be problematic finding any, given the limited outturn of 160 bottles (and indeed, it was something of a one-off, see my notes below this review).

Labelling the thing as an aguardiente (again, see further down) gives it a pretty broad umbrella, though clearly it is a cane juice derivative. It might have been better to use “cane spirit” to make the sale since aguardientes are a very loose category and present a moving target depending on where one is. Be that as it may, it is has all the hallmarks of a local back-country moonshine (decently made in this instance, to be sure), sporting the sort of artisanal handmade small-batch quality that makes rum geeks salivate as they search the world for the next clairin or grogue.

Labelling the thing as an aguardiente (again, see further down) gives it a pretty broad umbrella, though clearly it is a cane juice derivative. It might have been better to use “cane spirit” to make the sale since aguardientes are a very loose category and present a moving target depending on where one is. Be that as it may, it is has all the hallmarks of a local back-country moonshine (decently made in this instance, to be sure), sporting the sort of artisanal handmade small-batch quality that makes rum geeks salivate as they search the world for the next clairin or grogue.

When such micro-still quality is found, the production ethos behind it that makes it so attractive creates issues for their producers. The output tends to be small and not easily scaled up (assuming they even want to); there somewhat inconsistent quality from batch to batch, and some simply don’t hold up over time. Moreover, such aguardientes or charandas or agricoles or unaged spirits are usually not made for a discerning international rum audience, but for local and regional consumption, by and for people who don’t know (and don’t care) that there are certain markers of consistency and quality asked for by foreign audiences. It isn’t for such tourists that it’s made (a point Luca also thought long and hard about, before promoting the Haitian clairins back in 2014).

This aguardiente perfectly encapsulates that issue. It is a unique and unusual, very distinctive small batch agricole-style cane juice rum in all the ways that matter. It satisfies its local audience just fine. That it doesn’t fly as well past its own terroire may not be its problem, but ours. That said, you certainly won’t find me complaining about what it’s like, because I want me some more. And stronger, if I can get it.

(#843)(81/100)

Other Notes:

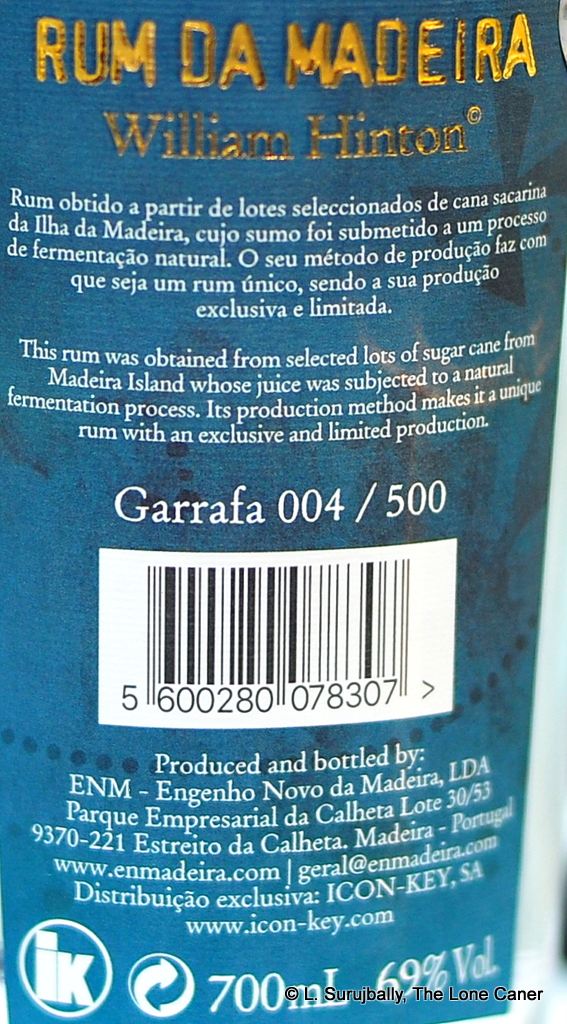

- The origin of the cane juice spirit / aguardiente is one of those near-unknown family stills that dot the Mexican back country (the Paranubes was like that also), and made, as stated above, more for village consumption than export. Here, it came from a three-column still tended by Sr. Delfino Cruz, which — if one can go by the label — is in the small village of San Pablo Ameyaltepec where he produces mostly mezcal. This tiny community of less than two hundred is in the state of Puebla, with the more famous state of Oaxaca on its southeast border: the El Destilado boys were sourcing mezcal from him.

- Charlie McKay, one of the founders, told me: “We actually only got one batch of the Aguardiente de Panela and then weren’t able to get it again. The Aguardiente was sourced while Michael and Jason were tasting some of Delfino’s mezcal and they noticed a bunch of liquid in drums, asked about it and he sheepishly allowed them to taste it. It’s sort of a side product he was making but more for locals rather than as his pride and joy. Anyway the liquid was super tasty and the guys bought a bunch of it on the spot. I believe, but I’d have to double check, that it was distilled in the same still that he makes his mezcal in. The panela aspect is the sugar he uses. Our current rum which is an Aguardiente de Caña is make from raw sugar cane juice, extracted straight from the plant and fermented. The panela is a preserved form of sugar that comes as set blocks […] usually from sort of conical shaped molds. It almost looks like a darker version of palm sugar that you’d get from an Asian grocer. Anyway this is rehydrated and fermented, then distilled which gives it a slightly different flavour profile to the more green Caña version. […] It was basically something Delfino wasn’t trying to sell us, but they boys saw it and had to taste it, then we got it, sold it all and now it’s gone.”

- The “Panela” in the title is named after panela, an unrefined sugar which is made by boiling and evaporating cane juice – it’s therefore something like India’s jaggery which we have come across before. Panela is commonly made around South America (especially Colombia) and it’s not a stretch to say aguardiente can be made from it, hence the name.

- The rum was distilled in a three column still and apparently fermented in tanks made of local pine wood – which is where the pine notes must have carried over from. It is likely that wild yeast was used for the fermentation.

- El Destilado, whose name is on the label, is a UK based indie bottler based on London, run by a trio of spirits enthusiasts — Michael Sager, Alex Wolpert and Charlie McKay; their tastes seem run more into agave spirits than rum per se since this was one of only two cane spirits they have released so far amidst a plethora of mezcals from Oaxaca. As a separate note, I like their minimalist design philosophy a lot.

- Another rum released by El Destilado is an equally obscure “Overproof” Oaxacan Rum at 52.3% which Alex over at The Rum Barrel took a look at a few months back.

A Brief Backgrounder on Mexican cane spirits and Agardientes

Having a large band of tropical climate and a vibrant sugar industry, it would be odd in the extreme if Mexico did not have rums in its alcoholic portfolio. The truth is that their artisanal, indigenous rums are actually not well known: not just because of the overwhelming popularity and market footprint of mezcal and tequila, but because rum brands like Bacardi, Mocambo, Prohibido, Tarasco and other popular low-cost “decent-enough” sellers have the limelight. They tend to stick with the tried and true model of standard-proof light blends of middling age to saturate (primarily) their own and the American market. So the backcountry small-batch rums of long-standing production — which in these days of full proof and indigenous tradition are sometimes overlooked — tend to have a hard time of it.

Leaving aside big brands and other alcoholic categories, however, there have always been many local cane distillates in Mexico, less exalted, less well known, often sniffed at. Some are as specific as charanda, others as wide ranging as aguardiente. The subject of today’s review is one of the latter, and if for purists it does not fall into our definitions of rum, I argue that if it’s a sugar cane distillate, it should be counted in “our” category, it needs a home and I’m perfectly happy to give it one.

Aguardientes – the word is a very broad catchall, akin to the generic English word “spirits,” translating loosely as fiery/burning water – are strong distilled alcoholic beverages, made from a variety of sources depending on the country or local tradition: macerated fruits (oranges, grapes, bananas, etc), grains (millet, barley, rice, beets, cassava, potatoes, tubers), or the classic sugar cane versions. They can be regulated under that name, and several have protected designations of origin.

Aguardiente as made in Mexico has a very supple definition, depending on where one is in that country and what the source material is. In some places it is a distilled cane spirit, in others it can be made from agave. It can be proofed down to 35%, or be stronger. It can be added to with spices, additives, you name it…or not. It’s either a poor man’s drink or a connoisseur’s delight, an indigenous low-quality moonshine or the next wave of craft spirit-making to enthuse young hipsters looking for The Next Big Thing.

Globally, for the purpose of those who primary spirit is rum, aguardientes are and should be limited to those which derive from cane juice only, and indeed many such spirits are properly labelled as aguardiente de cana, or some such titular linguistic variation (in Mexico this is particularly important because of the move to call agave spirts like mezcal aguardiente de agave and create a separation within the term). Unsurprisingly in a category this broad, clairins, grogues, guaros, puntas, charandas, even cachaças, are lumped into it, sometimes incorrectly – it’s a term which requires qualifying words to nail down precisely. But for the moment and this review, consider it a cane-juice-based, small-batch, local (even traditional) alcoholic beverage, and judge it on that basis.

Sources:

I have drawn on general background reading, personal experiences, wikipedia and the Rumcast interview with Francisco Terraza (timestamp 00:30:01) for some of the information on aguardientes generally and Mexico specifically

Addendum

After posting the link to this review on Reddit’s /r/rumserious (full disclosure – I am the moderator of that sub), City Barman made a comment that same evening which I felt was both enlightening and well written, and he kindly gave me permission to quote it here as an adjunct to the main review:

“Back in 2003, we went with a friend to visit his family in Oaxaca. We enjoyed an almost three week bacchanal, sampling as many of the local spirits as we could get our hands on. Tequila, mezcal and aguardiente de caña ran through our blood. The only real value of 90% of what we drank was its ability to get one drunk, on the way cheap. A far majority of it was tolerable to OK, from a taste standpoint, at least to my arrogant Western palate. 10%, however, was special, unique, sometimes divine, and as I found out later, often fleeting.

It’s a very different way of life, a very different culture that allows these incredibly small producers to exist. There is a very fine line separating them between “back-wood moonshiners” and “small batch artisans”. From month to month, a single distiller may find itself on different sides of said line. When one depends on naturally grown, fresh greens and wild, airborne yeast for the process, Mother Nature often overrides human intention. Replacing these things with more standardized, industrial methods would change the end product.

The process, by its very definition, is unpredictable and inefficient. It’s what makes the spirits cheap and “easy” to produce and also affordable to the masses. It’s also what typically creates the magic, when it happens, often entirely by accident. Unpredictable and inefficient are two qualities that ensure the likes of Diageo and Rémy Cointreau will go nowhere near the “category”, hence destroying it. The likes of Signor Gargano may find an audience for these unpredictable, small batches of joy. There may also be other producers, besides Señor Carrera, whose processes create a more consistent, predictable product.

Perhaps it’s perfectly fine and right that these spirits stay with their terroir. They represent the art in spirit making. Art that is intended for consumption, like live music and theater, is ephemeral and not entirely replicable. They also tend to be the ones that come closest to transporting their imbibers to Nirvana. Perhaps it’s good impetus to get us to escape our back yards, travel, and learn something about other human beings; their culture; their fears, hopes and dreams; their favorite drink.”

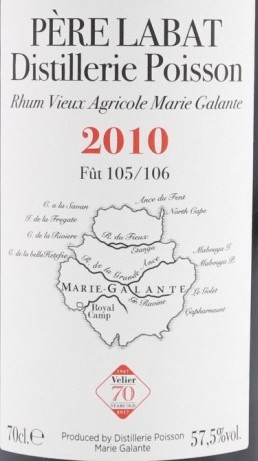

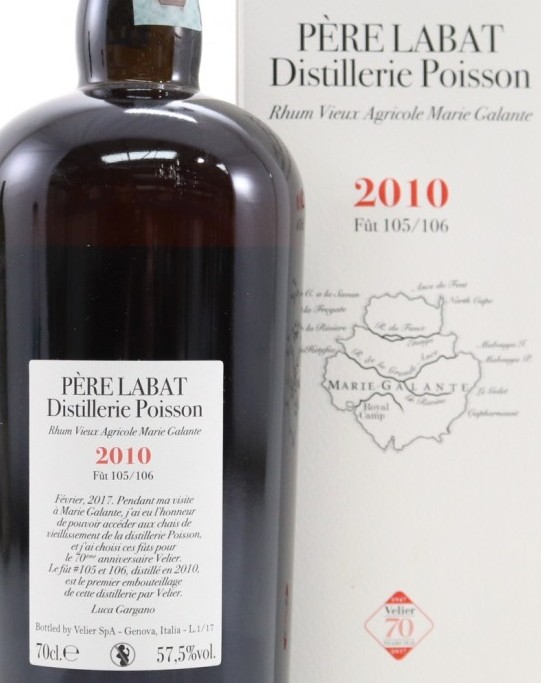

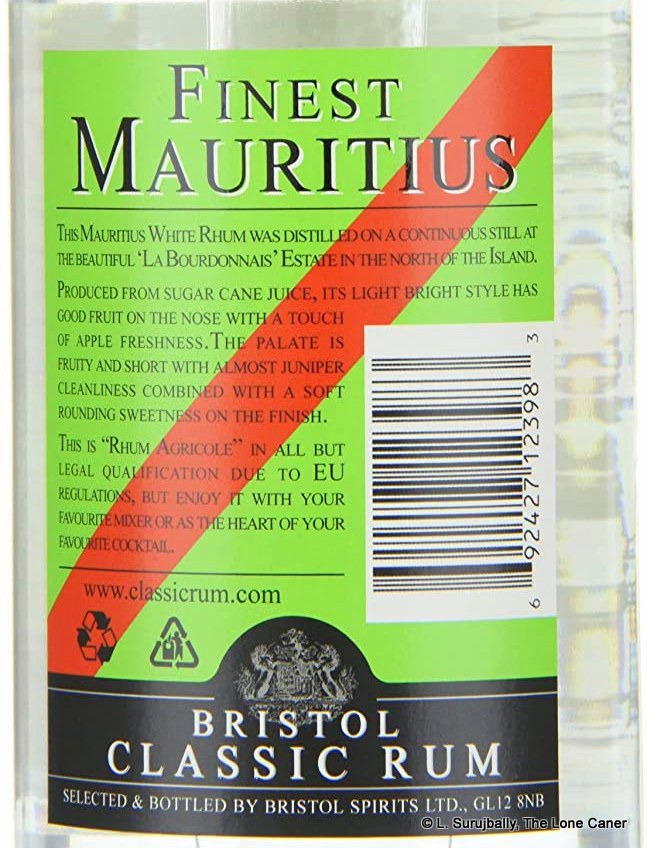

You would not necessarily believe that when you smell it, though. In fact, it smells decidedly odd on first examination: dusky, briny, with gherkins, olives, some pencil shavings, and lemon peel. This is followed up by herbs like dill and cardamom before doing a ninety degree hard right into laundry detergent, iodine, medicinals, the watery, slightly antiseptic scent of a swimming pool (and yes, I know how that sounds). Fruits are vague at best, and as a purported cane juice rum, this doesn’t much adhere to the profile of such a product.

You would not necessarily believe that when you smell it, though. In fact, it smells decidedly odd on first examination: dusky, briny, with gherkins, olives, some pencil shavings, and lemon peel. This is followed up by herbs like dill and cardamom before doing a ninety degree hard right into laundry detergent, iodine, medicinals, the watery, slightly antiseptic scent of a swimming pool (and yes, I know how that sounds). Fruits are vague at best, and as a purported cane juice rum, this doesn’t much adhere to the profile of such a product.

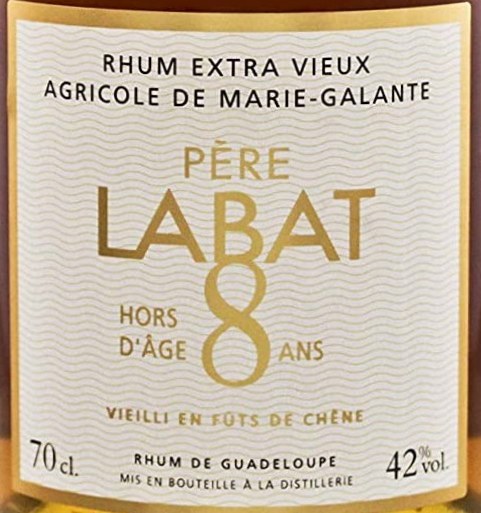

Whatever the case, I must advise you that if you like agricoles at all, those smaller names and lesser known establishments like Dillon should be on your radar. Not all of the rhums they make are double-digit aged, so those that are, even if farmed out to a third party, are even more worth looking at. Just smell this one, for example: it’s a fruitarian’s wet dream. In fact, the aroma almost strikes me like a very good Riesling mixing it up with a 7-up, if you could conceive of such an unlikely pairing. Lighter than the

Whatever the case, I must advise you that if you like agricoles at all, those smaller names and lesser known establishments like Dillon should be on your radar. Not all of the rhums they make are double-digit aged, so those that are, even if farmed out to a third party, are even more worth looking at. Just smell this one, for example: it’s a fruitarian’s wet dream. In fact, the aroma almost strikes me like a very good Riesling mixing it up with a 7-up, if you could conceive of such an unlikely pairing. Lighter than the

Depaz’s 45% rhum blanc agricole is not one of these uber-exclusive, limited-edition craft whites that uber-dorks are frothing over. But the quality and taste of even this standard white shows exactly how good the

Depaz’s 45% rhum blanc agricole is not one of these uber-exclusive, limited-edition craft whites that uber-dorks are frothing over. But the quality and taste of even this standard white shows exactly how good the

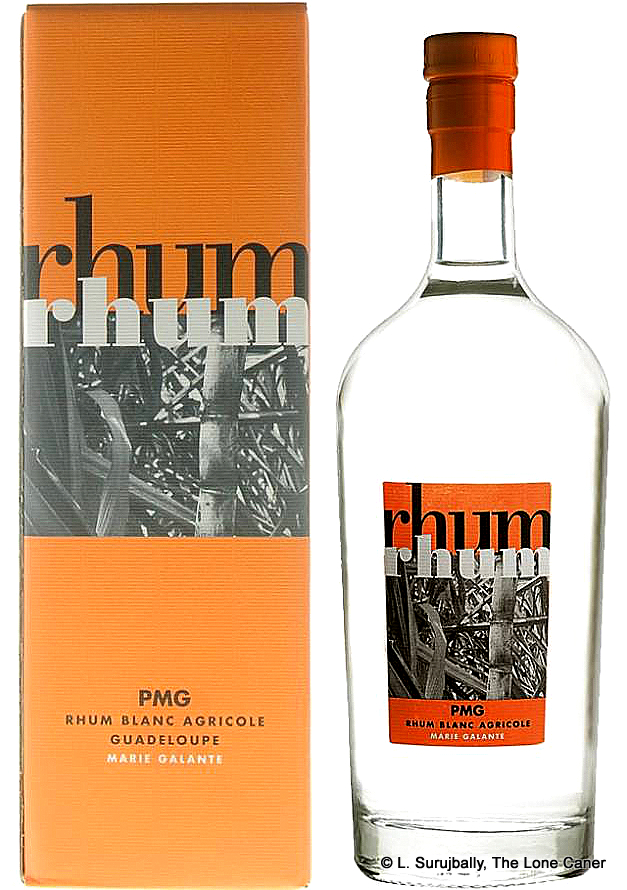

Although the plan was always to sell white (unaged) rhum, some was also laid away to age and the aged portion turned into the “Liberation” series in later years. The white was a constant, however, and remains on sale to this day – this orange-labelled edition was 56% ABV and I believe it is always released together with a green-labelled version at 41% ABV for gentler souls. It doesn’t seem to have been marked off by year in any way, and as far as I am aware production methodology remains consistent year in and year out.

Although the plan was always to sell white (unaged) rhum, some was also laid away to age and the aged portion turned into the “Liberation” series in later years. The white was a constant, however, and remains on sale to this day – this orange-labelled edition was 56% ABV and I believe it is always released together with a green-labelled version at 41% ABV for gentler souls. It doesn’t seem to have been marked off by year in any way, and as far as I am aware production methodology remains consistent year in and year out. From the description I’m giving, it’s clear that I like this rhum, a lot. I think it mixes up the raw animal ferocity of a more primitive cane juice rhum with the crisp and clear precision of a Martinique blanc, while just barely holding the damn thing on a leash, and yeah, I enjoyed it immensely. I do however, wonder about its accessibility and acceptance given the price, which is around $90 in the US. It varies around the world and on Rum Auctioneer it averaged out around £70 (crazy, since

From the description I’m giving, it’s clear that I like this rhum, a lot. I think it mixes up the raw animal ferocity of a more primitive cane juice rhum with the crisp and clear precision of a Martinique blanc, while just barely holding the damn thing on a leash, and yeah, I enjoyed it immensely. I do however, wonder about its accessibility and acceptance given the price, which is around $90 in the US. It varies around the world and on Rum Auctioneer it averaged out around £70 (crazy, since  In an ever more competitive market – and that includes French island agricoles – every chance is used to create a niche that can be exploited with first-mover advantages. Some of the agricole makers, I’ve been told, chafe under the strict limitations of the AOC which they privately complain limits their innovation, but I chose to doubt this: not only there some amazing rhums coming out the French West Indies within the appellation, but they are completely free to move outside it (as

In an ever more competitive market – and that includes French island agricoles – every chance is used to create a niche that can be exploited with first-mover advantages. Some of the agricole makers, I’ve been told, chafe under the strict limitations of the AOC which they privately complain limits their innovation, but I chose to doubt this: not only there some amazing rhums coming out the French West Indies within the appellation, but they are completely free to move outside it (as