Ten years ago, overproof rums (which I mentally designate as anything 70% ABV and above even though I’m well aware there are other definitions) were limited to the famed 151s – juice at 75.5%, often lightly aged, and designed as mixing agents of no particular distinction or sophistication. “Something tossed off in between more serious efforts,” I wrote once, not without a certain newbie disdain. They were fun to write about, but hardly “serious.”

But then over the years a strange thing happened – some producers, independents in particular, began releasing rums at serious cask strength and many were powerful and tasty enough to make the shortcomings of the 151s evident, and interest started to go in a different direction – stronger, not tied to a number, and either unaged or straight from the cask after some years. I don’t know if there was a sort of unspoken race to the top for some of these kinds of rums – but I can say that power and seriously good taste were and are not always mutually exclusive, and man, they just keep on getting better. They became, in short, very serious rums indeed.

Clearly the interest in knowing about, owning or just trying such record-setting rums is there. That said, clickbait listmakers don’t respond to the challenge with much in the way of knowledge. If you search “strongest rums in the world” then at the top comes this epically useless 2017 list from SpoonUniversity.com which was out of date even before it went to press. Then, there was a recent re-post of the not-really-very-good 2018 Unsobered “Definitive” list of the strongest rums in the world, which certainly wasn’t definitive in any sense but which got some attention, and an amazing amount of traction and commentary was showered on Steve Leukanech’s FB Ministry of Rum comment thread of the Sunset Very Strong the same week, and there’s always a bunch of good humoured and ribald commentary whenever someone puts up a picture of the latest monster of proof they found in some backwater bar, and tried.

And so, seeing that, I thought I would recap my experience with a (hopefully better) list of those explosive rums that really are among the strongest you can find. I won’t call mine “definitive” – I’m sure there’s stuff lurking around waiting to pounce on my glottis and mug my palate someplace – but it’s a good place to start, and better yet, I keep updating the list and have tried most, so there’s a brief blurb for each of those. I began at 70% and worked my way up in increasing proof points, not quality or preference (this created issues later as more and more rums blasted past that arbitrary marker, but to take a higher starting point would have meant excluding the 151s which was not something that sat well with me: and so, the list keeps getting longer. My bad).

Hope you like, hope you can find one or two, and whatever the case, have fun…but be careful when you do. Some of these rums are liquid gelignite with a short fuse, and should be handled with hat respectfully doffed and head reverently bowed.

Neisson L’Esprit Blanc, Martinique – 70%

Neisson L’Esprit Blanc, Martinique – 70%

Just because I only have one or two agricoles in this list doesn’t mean there aren’t others, just that I haven’t found, bought or tried them yet. There are some at varying levels of proof in the sixties, but so far one of the best and most powerful of this kind is this fruity, grassy and delicious 70% white rhino from one of the best of the Martinique estates, Neisson. Clear, crisp, a salty sweet clairin on steroids mixed with the softness of a good agricole style rum.

Jack Iron Grenada Overproof, Grenada – 70%

Jack Iron Grenada Overproof, Grenada – 70%

Westerhall, which is not a distillery, assembles this 140-proof beefcake in Grenada from Angostura stock from Trinidad, and it’s possibly named (with salty islander humour) after various manly parts. It’s not really that impressive a rum – an industrial column-still filtered white rarely is – with few exceptional tastes, made mostly for locals or to paralyze visiting tourists. I think if they ever bothered to age it or stop with the filtration, they might actually have something interesting here. Thus far, over and beyond local bragging rights, not really. Note that there was an earlier version at 75% ABV as well, made on Carriacou and now discontinued, but when it stopped being made is unclear.

L’Esprit Diamond 2005 11 YO, Guyana/France – 71.4%

L’Esprit Diamond 2005 11 YO, Guyana/France – 71.4%

L’Esprit out of Brittany may be one of the most unappreciated under-the-radar indies around and demonstrates that with this 11 year old rum from the Diamond column still, which I assumed to be the French Savalle, just because the flavours in this thing are so massive. Initially you might think that (a) there can’t be much flavour in something so strong and (b) it’s a wooden still — you’d be wrong on both counts. I gave this thing 89 points and it remains the best of the 70%-or-greater rums I’ve yet tried.

Takamaka Bay White Overproof, Seychelles – 72%

Takamaka Bay White Overproof, Seychelles – 72%

This Indian Ocean rum is no longer being made – it was discontinued in the early 2000s and replaced with a 69% blanc; still, I think it’s worth a try if you can find it. It’s a column still distillate with a pinch of pot still high-ester juice thrown in for kicks, and is quite a tasty dram, perhaps because it’s unaged and unfiltered. I think the 69% version is made the same way with perhaps some tweaking of the column and pot elements and proportions. Yummy.

Plantation Original Dark Overproof 73 %.

Plantation Original Dark Overproof 73 %.

Also discontinued and now replaced with the OFTD, the Original Dark was the steroid-enhanced version of the eminently forgettable 40% rum with the same name (minus “overproof”). Sourced from Trinidad (Angostura), a blend of young rums with some 8 YO to add some depth, and briefly aged in heavily charred ex-bourbon casks with a final turn in Cognac casks. Based on observed colour and tasting notes written by others, I think caramel was added to darken it, but thus far I’ve never tried it myself, since at the time when it was available I didn’t have it, or funds, available. I’ll pick one up one of these days, since I heard it’s quite good.

Lemon Hart Golden Jamaican Rum (1970s) – 73%

Lemon Hart Golden Jamaican Rum (1970s) – 73%

Since this rum – whose antecedents stretch back to the 1950s – is no longer in production either, it’s debatable whether to include it here, but it and others like it have been turning up at the new online auction sites with some regularity, and so I’ll include it because I’ve tried it and so have several of my friends. Blended, as was standard practice back then, and I don’t know whether aged or not…probably for a year or two. The taste, though – wow. Nuts, whole sacks of fruits, plus sawdust and the scent of mouldy long-abandoned libraries and decomposing chesterfields.

Longueteau Genesis, Guadeloupe – 73.51%

Longueteau Genesis, Guadeloupe – 73.51%

Not a rhum I’ve had the privilege of trying, but Henrik of the slumbering site RumCorner has, and he was batted and smacked flat by the enormous proof of the thing: “…overpowers you and pins you to the ground…and that’s from a foot away,” he wrote, before waxing eloquent on its heat and puissance, licorice, salt, grass and agricole-like character. In fact, he compared to a dialled-down Sajous, even though it was actually weaker than the Genesis, which says much for the control that Longueteau displayed in making this unaged blanc brawler. As soon as I was reminded about it, I instantly went to his dealer and traded for a sample, which, with my logistics and luck, should get in six months.

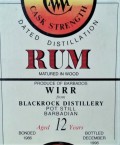

SMWS R3.5 “Marmite XO”, Barbados/Scotland – 74.8%

SMWS R3.5 “Marmite XO”, Barbados/Scotland – 74.8%

Richard Seale once fiercely denied that Foursquare had anything to do with either this or the R3.4, and he was correct – the rum came from WIRD. But there’s no dishonour attached to that location, because this was one strongly-made, strongly-tasting, well-assembled piece of work at a high proof, which any maker would have been proud to release. I liked it so much that I spent an inordinate amount of time lovingly polishing my language to give it proper respect, and both review and rum remain among my favourites to this day.

Forres Park Puncheon White Overproof, Trinidad – 75%

Forres Park Puncheon White Overproof, Trinidad – 75%

Meh. Cocktail fodder. Not really that impressive once you accept its growly strength. It used to be made by Fernandes Distillery before it sold out to Angostura and maybe it was better back then. The slick, cool, almost vodka-style presentation of the bottle hides the fact that the column still rum which was triple filtered (what, once wasn’t enough?) only tasted glancingly of sweet and salt and light fruits, but lacked any kind of individual character that distinguishes several other rums on this list (above and below it).

SMWS R3.4 “Makes You Strong Like a Lion” Barbados/Scotland – 75.3%

SMWS R3.4 “Makes You Strong Like a Lion” Barbados/Scotland – 75.3%

The L’Esprit 2005 got 89 points, but this one came roaring right behind it with extra five points of proof and lagged by one point of score (88). What an amazing rum this was, with a rich and sensuously creamy palate, bags of competing flavours and a terrific finish; and while hot and sharp and damned spicy, also eminently drinkable. Not sure who would mix this given the price or sip it given the proof. It’s a ball-busting sheep-shagger of a rum, and if it can still be found, completely worth a try or a buy, whatever is easier.

All the various “151” rums (no need to list just one) – 75.5%

All the various “151” rums (no need to list just one) – 75.5%

It may be unfair of me to lump all the various 151s together into one basket. They are as different as chalk and cheese among themselves – just see how wildly, widely variant the following are: Habitation Velier’s Forsythe 151 (Jamaica), Brugal (blanc), Tilambic (Mauritius), Lost Spirits “Cuban Inspired” (USA), Bacardi (Cuba), Lemon Hart (Canada by way of Guyana), Cavalier (Antigua), Appleton (Jamaica), and so on and so on. What unites them is their intent – they were all made to be barroom mixers, quality a secondary concern, strength and bragging rights being the key (the Forsythe 151 may be an exception, being more an educational tool, IMHO). Well, maybe. If I had a choice, I’d still say the Lemon Hart is a long standing favourite. But they all have something about them that makes them fun drinks to chuck into a killer cocktail or chug straight down the glottis. (Note: the link in the title of this entry takes you to a history of the 151s with a list of all the ones I’ve identified at the bottom).

There is also a 2022 cane juice release from Guadeloupe’s Bologne distillery that is bottled at 75.5% called ‘Brut de Colonne’ or “Still Strength”, which is rested, not aged, for 18 months. It is separate from the 151s and does not pretend to be one. This is not a rhum I’ve tried and do not consider as part of the 151 canon. As always, it looks interesting, though and one redditor gave it a 7.5/10 endorsement.

There is also a 2022 cane juice release from Guadeloupe’s Bologne distillery that is bottled at 75.5% called ‘Brut de Colonne’ or “Still Strength”, which is rested, not aged, for 18 months. It is separate from the 151s and does not pretend to be one. This is not a rhum I’ve tried and do not consider as part of the 151 canon. As always, it looks interesting, though and one redditor gave it a 7.5/10 endorsement.

Inner Circle Cask Strength 5 YO Rum (Australia) – 75.9%

Inner Circle Cask Strength 5 YO Rum (Australia) – 75.9%

This is a rum with a long history, dating back to the 1950s when the “Inner Circle” brand was first released in Australia. It was bottled in three strengths, which in turn were identified by coloured dots – Underproof (38-40%, the red dot), Overproof (57% or so, green dot) and 33 Overproof (73-75%, black dot).This last has now been resurrected and is for sale in Oz — I’ve not so far managed to acquire one. I’ve heard it’s a beast, though — so the search continues, since I’m as vain as anyone else who boasts about sampling these uber-mensches of rum, and don’t want the Aussies to have all the fun.

Plantation Jamaica (Long Pond) 1993 27 YO – 76.8%

Plantation Jamaica (Long Pond) 1993 27 YO – 76.8%

This is part of the Extreme Series, which are mostly (but not always) high proofed single cask rums; as always, there’s that last finishing in a <insert other cask type here>, the MF trademark despised villified by some but accepted by those with less of an axe to grind. This is a version I haven’t tried (too expensive) but I must admit that the strength and age have me intrigued. Picture taken from FB post on Rum Kingdom Group)

Velier Caroni 1982 23 YO Full Proof Rum – 77.3%

Velier Caroni 1982 23 YO Full Proof Rum – 77.3%

One of the classic canon of the Caronis released by Velier and now an object of cult worship, a unicorn rum for many. “A shattering experience” I wrote with trembling hands in 2017 and I meant it. Steroidal fortitude and a cheerful lack of caution for one’s health is needed to drink this rum; and it’s not the best Caroni out there…for sure it is one of the better ones, though. I don’t always agree with these multiple micro-bottlings from the same year that characterize the vast Velier Caroni output over the years, yet I also think that to dilute this thing down to a more manageable proof point would have been our loss. Now at least we can say we’ve had it. And take a week-long nap.

L’Esprit Beenleigh 2013 5YO Australian Rum – 78.1% and 2014 6 YO 78.%

L’Esprit Beenleigh 2013 5YO Australian Rum – 78.1% and 2014 6 YO 78.%

Australia adds another to the list with this European bottling of rum from the land of Oz, and another released a year later. The first is a sharp knife to the glottis, a Conrad-like moment of stormy weather. The second, with an additional year of ageing, is much tamer, much better, though still seriously strong. What surprises, after one recovers, is how traditional both seem (aside from the power) – you walk in expecting a Bundie, say, but emerge with a jacked-up Caribbean-type rum. That doesn’t make either one bad in any sense, just two very interesting overproofs from a country whose rums we don’t know enough about.

Stroh 80, Austria – 80%

Stroh 80, Austria – 80%

Apparently Stroh does indeed now use Caribbean distillate for their various proofed expressions, and it’s marginally more drinkable these days as a consequence. The initial review I did was the old version, and hearkens back to rum verschnitt that was so popular in Germany in the 19th and early 20th century. Not my cup of tea, really. A spiced rum, and we have enough real ones out there for me not to worry too much about it. It’s strong and ethanol-y as hell, and should only be used as a flavouring agent for pastries, or an Austrian jägertee.

Denros Strong Rum, St Lucia – 80%

Denros Strong Rum, St Lucia – 80%

A filtered white column still rum from St. Lucia Distillers, it’s not made for export and remains most common on the island. It is supposedly the base ingredient for most of the various “spice” rums made in rumshops around the island, but of course, locals would drink it neat or with coconut water just as fast. So far I’ve not managed to track a bottle down for myself — perhaps it’s time to see if it’s as good as rumour suggests it is.

SMWS R5.1 Long Pond 9 Year Old “Mint Humbugs”, Jamaica/Scotland – 81.3%

SMWS R5.1 Long Pond 9 Year Old “Mint Humbugs”, Jamaica/Scotland – 81.3%

This is a rum that knocked me straight into next week, and I’ve used it to smack any amount of rum newbs in Canada down the stairs. Too bad I can’t ship it to Europe to bludgeon some of my Danish friends, because for sure, few have ever had anything like it and it was the strongest and most badass Jamaican I’ve ever found before the Wild Tiger roared onto the scene and dethroned it. And I still think it’s one of Jamaica’s best overproofs.

L’Esprit South Pacific Distillery 2018 Unaged White – 83%

L’Esprit South Pacific Distillery 2018 Unaged White – 83%

Strong, amazing flavour profile, pot still, unaged, and a mass of flavour. I’m no bartender or cocktail guru, but even so I would not mix this into any of the usual simple concoctions I make for myself….it’s too original for that. It’s one of a pair of white and unaged rums L’esprit made, both almost off the charts. Who would ever have thought there was a market for a clear unaged white lightning like this?

Sunset Very Strong, St. Vincent – 84.5%

Sunset Very Strong, St. Vincent – 84.5%

The rum that was, for the longest while, the Big Bad Wolf, spoken of in hushed whispers in the darkened corners of seedy bars with equal parts fear and awe. It took me ages to get one, and when I did I wasn’t disappointed – there’s a sweet, light-flavoured berry-like aspect to it that somehow doesn’t get stomped flat by that titanic proof. I don’t know many who have sampled it who didn’t immediately run over to post the experience on social media, and who can blame them? It’s a snarling, barking-mad street brawler, a monster with more culture than might have been expected, and a riot to try neat.

L’Esprit Diamond 2018 Unaged White – 85%

L’Esprit Diamond 2018 Unaged White – 85%

Just about the most bruisingly shattering overproof ever released by an independent bottler, and it’s a miracle that it doesn’t fall over its strength and onto its face (like, oh the Forres Park, above). It does the Habitation Velier PM one better in strength though not being quite as good in flavour. Do I care? Not a bit, they’re brothers in arms, these two, being Port Mourant unaged distillates and leaves off the same branch of the same tree. It shows how good the PM wooden still profile can be when carefully selected, at any strength, at any age.

Romdeluxe “Wild Tiger” 2018, Jamaica/Denmark – 85.2%

Romdeluxe “Wild Tiger” 2018, Jamaica/Denmark – 85.2%

Wild Tiger is one of many “wildlife” series of rums released thus far (2019) by Romdeluxe out of Denmark, their first. It gained instant notoriety in early 2019 not just by it handsome design or its near-unaged nature (it had been rested in inert tanks for ten years, which is rather unusual, then chucked into ex-Madeira casks for three months) but its high price, the massive DOK-level ester count, and that screaming proof of 85.2%. It was and is not for the faint of heart or the lean of purse, that much is certain. I cross myself and the street whenever I see one. Since then Rom Deluxe has released several strong rums in the 80% or greater range.

Marienburg 90, Suriname – 90%

Marienburg 90, Suriname – 90%

Somewhere out there there’s a rum more powerful than this, but you have to ask what sane purpose it could possibly serve when you might as well just get some ethanol and add a drop of water and get the Marienburg (which also makes an 81% version for export – the 90% is for local consumption). There is something in the Surinamese paint stripper, a smidgen of clear, bright smell and taste, but this is the bleeding edge of strength, a rum one demerit away from being charged with assault with intent to drunk — and at this stage and beyond it, it’s all sound and fury signifying little. I kinda-sorta appreciate that it’s not a complete and utter mess of heat and fire, and respect Marienburg for grabbing the brass ring. But over and beyond that, there’s not much point to it, really, unless you understand that this is the rum Chuck Norris uses to dilute his whisky.

Rivers Antoine 180 Proof White Grenadian Rum – 90%

Rivers Antoine 180 Proof White Grenadian Rum – 90%

I’ve heard different stories about Rivers’ rums, of which thus far I’ve only tried and written about the relatively “tame” 69% – and that’s that the proof varies wildly from batch to batch and is never entirely the strength you think you’re getting. It’s artisanal to a fault, pot stilled, and I know the 69% is a flavour bomb so epic that even with its limited distribution I named it a Key Rum. I can only imagine what a 90% ABV version would be like, assuming it exists and is not just an urban legend (it is included here for completeness). If it’s formally released to the market, then I’ve never seen a legitimizing post, or heard anyone speak of it as a fact, ever. Maybe anyone who knows for sure remained at Rivers after a sip and has yet to wake up.

Rom Deluxe “Destillation Strength” Dominican Republic 474 Esters Unaged Rum – 93% ABV

Rom Deluxe “Destillation Strength” Dominican Republic 474 Esters Unaged Rum – 93% ABV

In March 2022, the Marienburg lost the crown after reigning just about undisputed since, oh, whenever it was issued. I have no idea what possessed Rom Deluxe out of Denmark to release this MechaRumzilla, but my God, I have to get me a bottle. Because the issue behind all the metaphors and flowery language a review would inevitably entail, is this: can a rum maintain a taste profile worth drinking in any way, even when stuffed with esters, at that strength? Can’t wait to shred my tonsils and find out.

Additions and honourable mentions, added after the original list Was published in 2019

Unsurprisingly, people were tripping over themselves to send me candidates that should make the list, and there were some that barely missed the cut – in both cases, I obviously hadn’t known of or tried them, hence their inadvertent omission. Here are the ones that were added after the initial post came out, and you’ll have to make your own assessment of their quality, or let me know of your experience.

Old Brothers Hampden 86.3% LROK White Rum

Old Brothers Hampden 86.3% LROK White Rum

360 bottles of this incredibly ferocious high ester rum were released by a small indie called Old Brothers around 2019 , and the juice was stuffed into small flasks of surpassing simplicity and aesthetic beauty. Even though I haven’t tasted it (a post about it on FB alerted me to its existence). I can’t help but desire a bottle, just because of its ice-cold blonde-femme-fatale looks, straight out of some Hitchcock movie where the dame offs the innocent rum reviewer right after love everlasting is fervently declared.

Maggie’s Farm Airline Proof – 70%

Maggie’s Farm Airline Proof – 70%

Maggie’s Farm is an American Distillery I’ve heard a fair bit about but whose products I’ve not so far managed to try. Their cheekily named Airline Proof clocks in at the bottom end of my arbitrary scale, is a white rum, and I expect it was so titled so as to let people understand that yes, you could in fact take it on an airplane in the US and not get arrested for transporting dangerous materials and making the world unsafe for democracy.

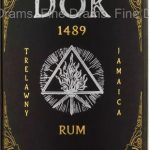

DOK – Trelawny Jamaica Rum – Aficionados x Fine Drams – 69% / 85.76%

DOK – Trelawny Jamaica Rum – Aficionados x Fine Drams – 69% / 85.76%

Here’s a fan-released DOK for sale on Fine Drams, and while originally it oozed off the still at 85.76% and close to the bleeding max of esterland (~1489 g/hLPA), whoever bottled it decided to take the cautious approach and dialled it down to the for-sale level of 69%. Even at that strength, I was told it sold out in fifteen minutes, which means that whatever some people dismissively say about the purpose of a DOK rum, there’s a market for ’em. Note that RomDelux did in fact release 149 bottles at full 85.76% still strength, as noted by a guy in reddit here, and another one here.

(Click photo to expand)

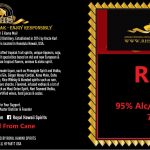

Royal Hawaiian Spirits 95% Rum

In May 2020 the RHS Distillery on Maui (Hawaii), which rather amusingly calls itself the “Willie Wonka of alcohol” applied for TTB label approval for a 95% rum which immediately drew online sniffs of disapproval for being nothing more than a vodka at best, grain neutral spirit at worst – because at that strength just about all the flavour-providing congeners have been stripped out. Nevertheless, though the company seems to operate an industrial facility making a wide range of distilled spirits for all comers (very much like Florida Distillers who make Ron Carlos, you will recall), if their claim that this product is made from cane is true then it is still a rum (barely) and must be mentioned. I must say, however, I would approach tasting it with a certain caution…and maybe even dread. For sure this product will hold the crown for the strongest rum ever made, for the foreseeable future, whatever its quality, or lack thereof.

Plantation Extreme No. 4 Jamaica (Clarendon) 35 YO 74.8%

Plantation Extreme No. 4 Jamaica (Clarendon) 35 YO 74.8%

Plantation should not be written off from consumers tastes simply because it gets so much hate for its stance on Barbados and Jamaican GIs. It must be judged on the rums it makes as well, and the Extreme series of rums, which take provision of information to a whole new level and are bottled at muscular cask strengths, every time (plus, I think they dispensed with the dosage). This one, a seriously bulked up Jamaican, is one of the beefier ones and I look forward to trying it not just for the strength, but that amazing (continental) age.

Dillon Brut de Colonne Rhum Blanc Agricole 71.3%

Dillon Brut de Colonne Rhum Blanc Agricole 71.3%

An unaged white rhum from Martinique’s Dillon distillery, about which we don’t know enough and from which we don’t try enough. This still-strength beefcake is likely the strongest they have ever made or will ever make…until the next one, and Pete Holland of the Floating Rum Shack twigged me on to it (that’s his picture, so thanks Pete!) remarking “Once you try high proof, is it ever possible to go back?” A good question. I probably need to find this thing just to see, and for sure, if it comes up to scratch, it’ll make my third list of great white rums when the time comes.

Velier Caroni 1982 Heavy 23 YO (1982 – 2005) 77.3% | Caroni 1985 Heavy 20 YO (1985 – 2005) 75.5% | Caroni 1996 Heavy 20 YO (1996-2016)(Cask R3721) Legend” 70.8% | Caroni 1996 Heavy 20 YO (1996-2016)(Cask R3718) Legend” 70.8% | Caroni 1996 “Trilogy” Heavy (1996 – 2016) 70.28%

Velier Caroni 1982 Heavy 23 YO (1982 – 2005) 77.3% | Caroni 1985 Heavy 20 YO (1985 – 2005) 75.5% | Caroni 1996 Heavy 20 YO (1996-2016)(Cask R3721) Legend” 70.8% | Caroni 1996 Heavy 20 YO (1996-2016)(Cask R3718) Legend” 70.8% | Caroni 1996 “Trilogy” Heavy (1996 – 2016) 70.28%

Five of Velier’s legendary Caronis make this list, all clocking in at 70% ABV or greater. They are, unsurprisingly, hard to get at reasonable prices nowadays, and to some extent there’s a real similarity among them all, since they are varied branches off the same tree. Once hardly known, their reputation and their cost has exploded over the last five years and any one of them would be a worthy purchase – and with its mix of fusel oil, dark fruits, tar, wood chips and no shortage of amazing flavours, I’d say the 77.3% gets my vote for now. Serge thought so too, back in the day….but beware of the price tag, which recently topped £2600 just a few months ago at auction.

Cadenhead Single Cask Black Rock WIRR 1986-1998 12 YO 73.4%

Cadenhead Single Cask Black Rock WIRR 1986-1998 12 YO 73.4%

Another rum I have not gotten to try, one of the varied editions of the famed but nonexistent 1986 Rockley pot still from WIRD (Rockely is best described as a style, since no such still actually exists). At a stunning 73.4% this is a surprisingly hefty rum to have come out of the 1990s, when rum was just making its first baby steps to becoming more than a light Cuban blend wannabe. Few have managed to try it, fewer still to write about it. Marius of Single Cask (from whom I pilfered the picture) is one of them, and he, even though not entirely won over by it, still gave the rum a solid 87 points.

Saint James Brut de Colonne Rhum Agricole Blanc BIO 74.2%

Saint James Brut de Colonne Rhum Agricole Blanc BIO 74.2%

After having tried Saint James’s titanically flavoured pot still juice, it’s a no-brainer that this 100% organic unaged white rum powered by 74.2% of mad horsepower is something which I and any lover of white column still juice has to get a hold of. Stuff like this makes the soft light white mixers of the 60s scurry home to hide in their mama’s skirts, and will cheerfuly blow up any unprepared glottis that doesn’t pay it the requisite respect. I can’t wait to try it myself.

Pere Labat 70.7 Rhum Blanc Agricole (Brut de Colonne) 70.7%

Pere Labat 70.7 Rhum Blanc Agricole (Brut de Colonne) 70.7%

Indies and the agricole makers are sure raising the bar for overproofs. Here’s a lovely still-strength white agricole that just squeaks by the arbitrary bar I set to cut off the wannabes. I don’t know how good it is but Facebook chatter suggests it’s intense, smoky, salty and comes with optional extra-length claws to add to the fangs it already has. I want one of these for myself.

Rom Deluxe Jamaicans (Hampden) – R.17 “Rhino” 5th Anniversary Edition 2019-2021 <2 YO 86.2% | R.20 “Springbok” (C<>H) 2020-2022 86% | R.23 “Pronghorn” (C<>H) 2020-2021 < 2YO 86% | R.32 “Wolf” (HGML) 2020-2022 <2YO 86%

Rom Deluxe Jamaicans (Hampden) – R.17 “Rhino” 5th Anniversary Edition 2019-2021 <2 YO 86.2% | R.20 “Springbok” (C<>H) 2020-2022 86% | R.23 “Pronghorn” (C<>H) 2020-2021 < 2YO 86% | R.32 “Wolf” (HGML) 2020-2022 <2YO 86%

I have to get myself some of these. These are all weapons grade rums, the sort of thing tinpot banana-republic dictators only wish they had in their arsenals to dissuade unwashed insurrectionists who insist on weird things like, you know, their rights. By now Rom Deluxe has morphed into a full blown Indie, and I wonder if they deliberately seek out rums like this to blow our minds. It’s a full blown Hampden pot still rum from Jamaica, and yes, it’s a high-ester DOK funk bomb as well. Go wild.

Barikken (France) Montebello Distillery 81.6º Brut de Colonne (Unaged)

Barikken (France) Montebello Distillery 81.6º Brut de Colonne (Unaged)

Unaged, white, clean, agricole. Gradually the agricole makers are coming up to the level of the Latin/Cuban and English style monsters of proof, though one could reasonably ask why they bother. The taste profile of this one is almost, but not quite taken over by the power of its strength, and is a fitting answer why at least they wanted to try…and should try for even more in the years to come. It’s really quite something.

Montebello Edition Oge Cheapfret Brut de Colonne 77% ABV (Unaged)

Montebello Edition Oge Cheapfret Brut de Colonne 77% ABV (Unaged)

Not to be outdone, Montebello released an unaged column still white of their own, though not quite as powerful; I think this came out in 2021 or 2022. So far I have yet to taste it and can’t provide much commentary.

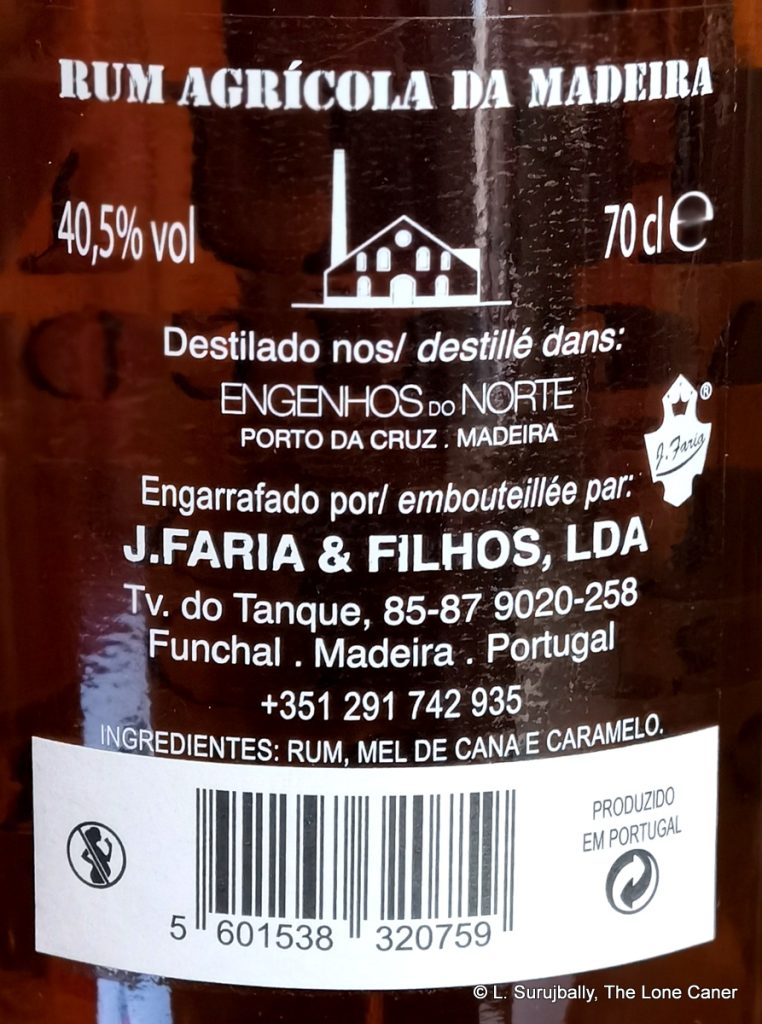

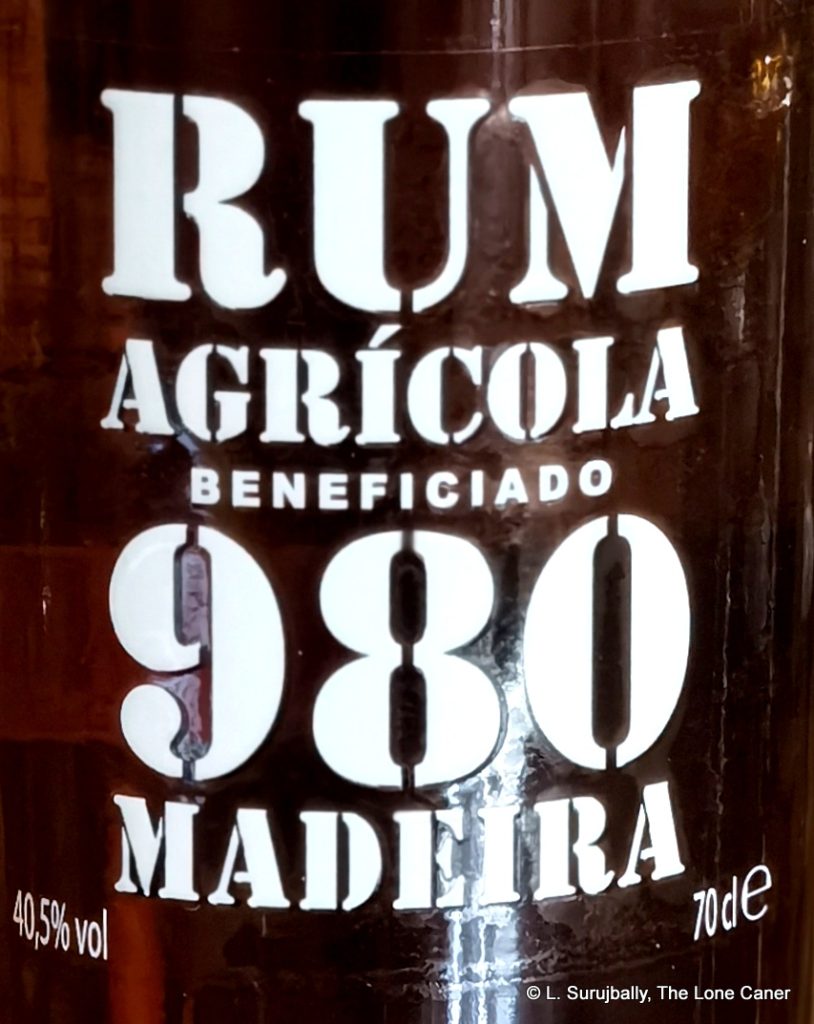

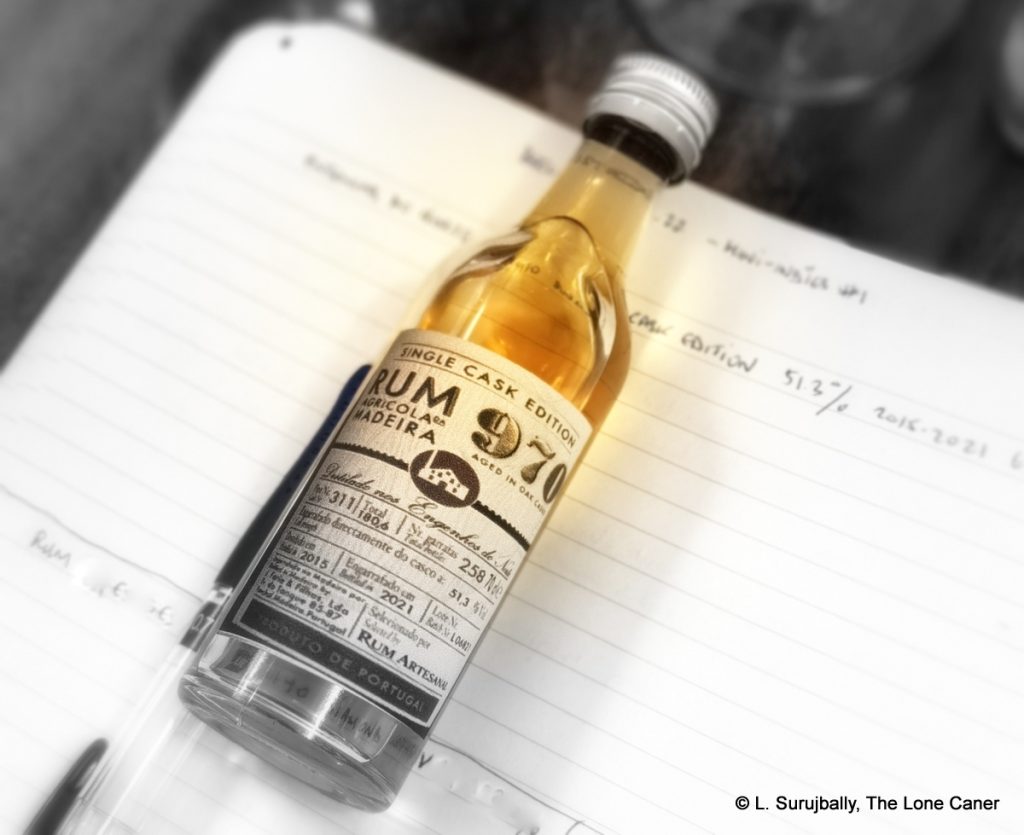

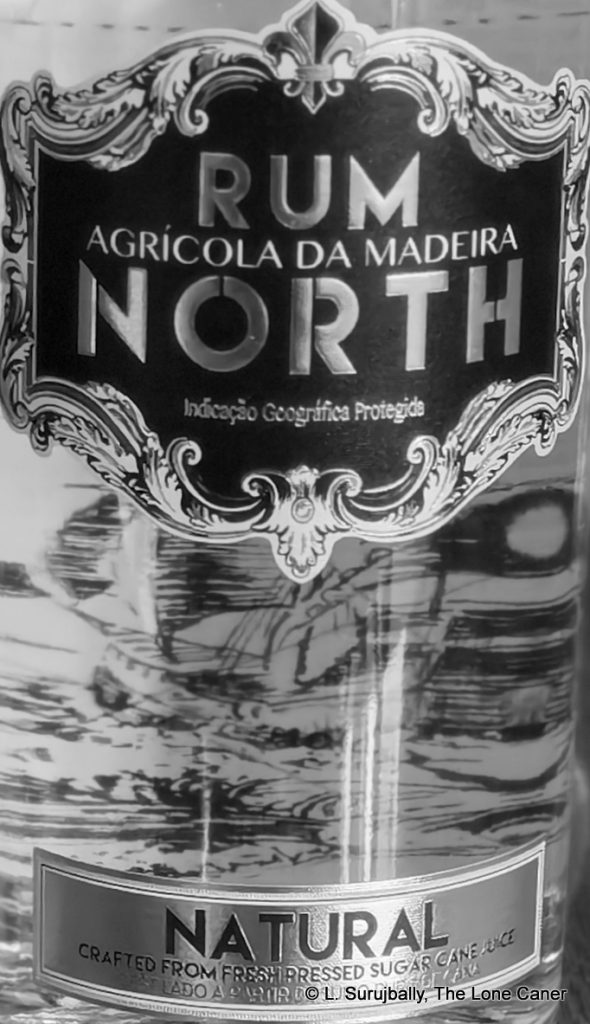

Engenho do Norte Branca 78% ABV and Branca Brut de Colonne 79.4%

Engenho do Norte Branca 78% ABV and Branca Brut de Colonne 79.4%

Engenho do Norte is a distillery located on the north coast of Madeira and they have several lines of rums: Rum North, Zarco, 980, 970, Lido, and the cane-juice agricoles of the “Branca” or “White” series. These come in several varieties, from a sedate 40%, up to the previous Big Gun, the 60% “Fire”. In April 2022 a new version without a name was promoted, setting a new proof point record for the company of 78% ABV – but so far I have not seen any reviews or comments, and it has still not made it to the company website, probably because they’re afraid it might spontaneously combust. It was followed in late 2022 by another Brut de Colonne at 79.4%. Wow….

Distillerie de Taha’a, Pari Pari, French Polynesia – “T” Double Distillation 74º

Distillerie de Taha’a, Pari Pari, French Polynesia – “T” Double Distillation 74º

I’m fairly sure nobody outside the region has heard much about this small distillery in French Polynesia. Yet they seem to have made a quiet reputation for themselves over the last four or five years. Their products are cane juice rhums for the most part (Rum-X lists a dozen or so), at various strengths and with occasional ageing, and finishes. This double distilled agricole-style rhum is definitely one I want to try: for its strength, its terroire, its origin and yes, damn it, for sheer curiosity. (NB: I can’t remember where I picked the photo from — it languished in my to-do basket for a while — so I apologize to the owner for the lack of attribution – will correct if notified).

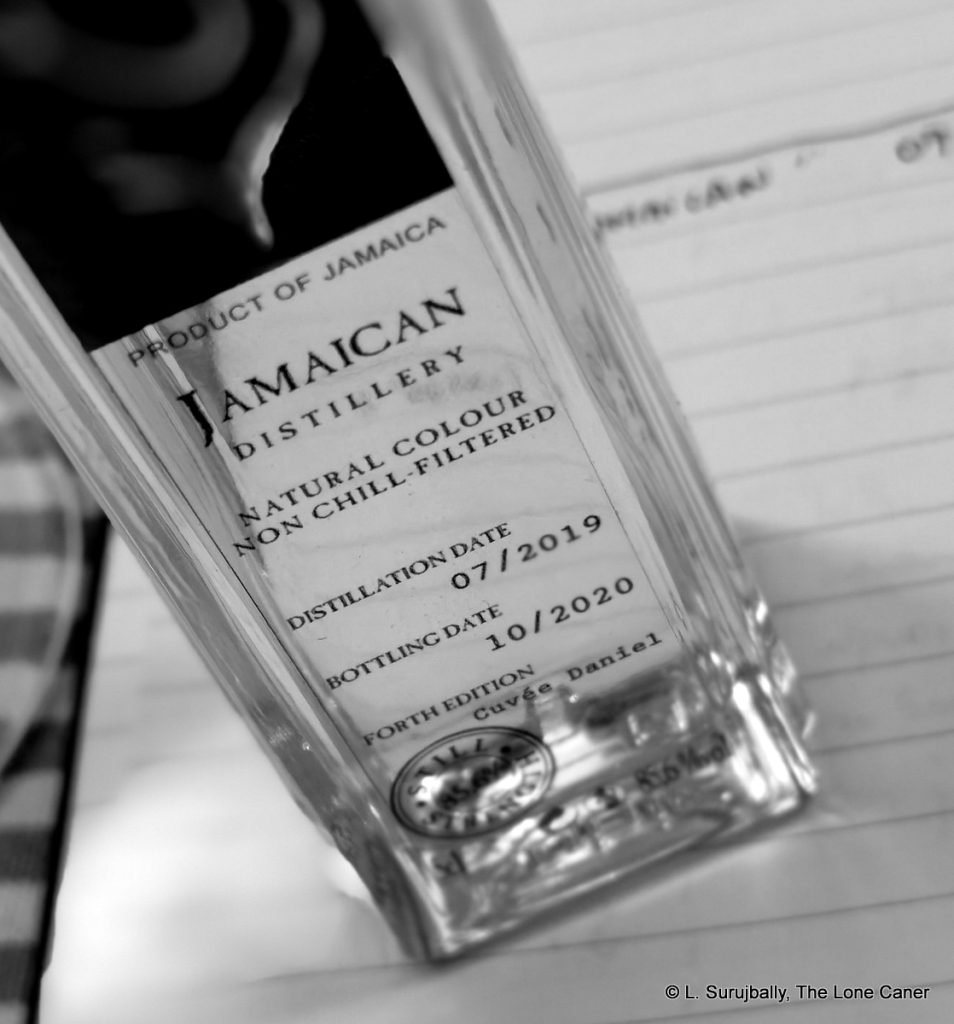

L’Esprit Still Strength “A Jamaican Distillery” 2019 Unaged White Rum – 85.6%

L’Esprit Still Strength “A Jamaican Distillery” 2019 Unaged White Rum – 85.6%

I’m not sure if L’Esprit has gone off on a tangent with these massive overproofs. I thought the Fiji and Diamond were pretty much the standard badasses the company put out; not so – in 2020 Tristan clearly wanted to outdo his previous efforts and issued 279 copies of this Jamaican monster. I have a sample dissolving a bottle somewhere in a lead lined box suspended in superconducting coils channelling a magnetic field to keep it from doing some weird scientific sh*t…like maybe creating a singularity. But I can’t wait to try this one (Update…and I finally did, in November 2022).

Mhoba (South Africa) High Ester Pot Still Rums – Mar 2019 74.5% and Jul 2019 78.2%

Mhoba (South Africa) High Ester Pot Still Rums – Mar 2019 74.5% and Jul 2019 78.2%

Mhoba has been making big waves since it debuted a few years ago, mostly because of its high quality aged and unaged pot still juice. They have branched out some into flavoured rums, high ester rums and strong badasses starting north of 65%, and the two mentioned here are just some of what’s going to become available in years to come. I don’t know if there’s a race to go past 90% these days – sometimes it sure seems so, what with the stronger and stronger rums that keep getting issued.

Hampden 2023/2025 ‘HLCF’ Jamaican Rum (83.4%, The Colours of Rum)

Hampden 2023/2025 ‘HLCF’ Jamaican Rum (83.4%, The Colours of Rum)

This is another one of those rums that has such a minimal outturn (60 bottles) that to find it is an exercise in futility, unless one has conta cts at Hampden or Velier, otr regularly attends all the European festivals. Still, it’s Hampden and HLCF, so I don’t doubt it is a good rujm… if one can get past that cardiac ibducing strength. As of 2025 it sure seems that single barrel rums at stuill strength or barrel strength are becoming more prevalent, thogh one wonders who drinks these things, or for what purpose they buy them.

If I had to chose the best of the lot I’d have to say the Neisson, the SMWSs and the L’Esprits vie for the top spots, with the Wild Tiger coming in sharp right behind them, and I’d give a fond hat-tip to both the old and new Lemon Harts. The French island agricoles as a whole tend to be very very good. This is completely subjective of course, and frankly it might be better to start with which is worst and move up from there, rather than try and go via levels of force, as I have done.

Clearly though, just because some massively-ripped and generously-torqued overproof rum is aged for years, doesn’t means it is as good or better than some unaged white at a lower strength (or a higher one). Depending on your tastes, both can be amazing…for sure they’re all a riotous frisson of hot-snot excitement to try. On the flip side, the Marienburg suggests there is an upper limit to this game, and I think when we hit around 90% or thereabouts, even though there’s stronger, we ram into a wall — beyond which lies sh*t-and-go-blind madness and the simple lunacy of wanting to just say “I made the strongest” or “I drank it.” without rhyme or reason. I know there’s a 96% beefcake out there, but so far I’ve not found it to sample myself, and while it is a cardinal error to opine in advance of personal experience in these matters, I can’t say that I believe it’ll be some earth shaking world beater. By the time you hit that strength you’re drinking neutral alcohol and unless there’s an ageing regiment in place to add some flavour chops, why exactly are you bothering to drink it?

But never mind. Overproofs might originally have been made to be titanic mixers and were even, as I once surmised, throwaway efforts released in between more serious rums. But rums made by the SMWS, Romdeluxe, L’Esprit and others have shown that cask strength juice with minimal ageing, if carefully selected and judiciously issued, can boast some serious taste chops too, and they don’t need to be aiming for the “Most Powerful Rum in the World” to be just damned fine rums. If you want the street cred of actually being able to say you’ve had something stronger than any of your rum chums, this list is for you. Me, I’d also think of it as another milestone in my education of the diversity of rum.

And okay, yeah, maybe after drinking one of these, I would quietly admire and thump my biscuit chest in the mirror once or twice when Mrs. Caner isn’t looking (and snickering) and chirp my boast to the wall, that “I did this.” I could never entirely deny that.

Other notes

- In my researches I found a lot of references to the Charley’s JB Overproof Rum at 80% ABV; however, every photo available online is a low-res copy of the 63% version which I wrote about already, so I could not include it as an entry without better, umm, proof.

- Thanks to Matt, Gregers and Henrik who added suggestions.

Consider first the nose: it is instantly pungent, rather thick and redolent of ripe dark fruits – prunes, plums, raisins, peaches in syrup, and has that slight tart sourness of ripe Kenyan mangoes. It smells much firmer and more solidly constructed than Engenhos’s standard agricolas from the North brand line. It remains, for most of the duration one smells it, somewhat thickly sweet mixed with light citrus and crisper fruit, and thankfully never cloying. Whispers of Danish pastries, caramel, vanilla, guavas and a faint touch of orange zest and a whiff of rubber round things out nicely

Consider first the nose: it is instantly pungent, rather thick and redolent of ripe dark fruits – prunes, plums, raisins, peaches in syrup, and has that slight tart sourness of ripe Kenyan mangoes. It smells much firmer and more solidly constructed than Engenhos’s standard agricolas from the North brand line. It remains, for most of the duration one smells it, somewhat thickly sweet mixed with light citrus and crisper fruit, and thankfully never cloying. Whispers of Danish pastries, caramel, vanilla, guavas and a faint touch of orange zest and a whiff of rubber round things out nicely

Neisson L’Esprit Blanc, Martinique – 70%

Neisson L’Esprit Blanc, Martinique – 70% Jack Iron Grenada Overproof, Grenada – 70%

Jack Iron Grenada Overproof, Grenada – 70% L’Esprit Diamond 2005 11 YO, Guyana/France – 71.4%

L’Esprit Diamond 2005 11 YO, Guyana/France – 71.4% Takamaka Bay White Overproof, Seychelles – 72%

Takamaka Bay White Overproof, Seychelles – 72% Plantation Original Dark Overproof 73 %.

Plantation Original Dark Overproof 73 %.

Longueteau Genesis, Guadeloupe – 73.51%

Longueteau Genesis, Guadeloupe – 73.51% SMWS R3.5 “Marmite XO”, Barbados/Scotland – 74.8%

SMWS R3.5 “Marmite XO”, Barbados/Scotland – 74.8% Forres Park Puncheon White Overproof, Trinidad – 75%

Forres Park Puncheon White Overproof, Trinidad – 75% SMWS R3.4 “Makes You Strong Like a Lion” Barbados/Scotland – 75.3%

SMWS R3.4 “Makes You Strong Like a Lion” Barbados/Scotland – 75.3%

Inner Circle Cask Strength 5 YO Rum (Australia) – 75.9%

Inner Circle Cask Strength 5 YO Rum (Australia) – 75.9%

SMWS R5.1 Long Pond 9 Year Old “Mint Humbugs”, Jamaica/Scotland – 81.3%

SMWS R5.1 Long Pond 9 Year Old “Mint Humbugs”, Jamaica/Scotland – 81.3% L’Esprit South Pacific Distillery 2018 Unaged White – 83%

L’Esprit South Pacific Distillery 2018 Unaged White – 83% Sunset Very Strong, St. Vincent – 84.5%

Sunset Very Strong, St. Vincent – 84.5% L’Esprit Diamond 2018 Unaged White – 85%

L’Esprit Diamond 2018 Unaged White – 85% Romdeluxe “Wild Tiger” 2018, Jamaica/Denmark – 85.2%

Romdeluxe “Wild Tiger” 2018, Jamaica/Denmark – 85.2% Marienburg 90, Suriname – 90%

Marienburg 90, Suriname – 90%

DOK – Trelawny Jamaica Rum – Aficionados x Fine Drams – 69% / 85.76%

DOK – Trelawny Jamaica Rum – Aficionados x Fine Drams – 69% / 85.76%

Plantation Extreme No. 4 Jamaica (Clarendon) 35 YO 74.8%

Plantation Extreme No. 4 Jamaica (Clarendon) 35 YO 74.8% Dillon Brut de Colonne Rhum Blanc Agricole 71.3%

Dillon Brut de Colonne Rhum Blanc Agricole 71.3% Velier Caroni 1982 Heavy 23 YO (1982 – 2005) 77.3% | Caroni 1985 Heavy 20 YO (1985 – 2005) 75.5% | Caroni 1996 Heavy 20 YO (1996-2016)(Cask R3721) Legend” 70.8% | Caroni 1996 Heavy 20 YO (1996-2016)(Cask R3718) Legend” 70.8% | Caroni 1996 “Trilogy” Heavy (1996 – 2016) 70.28%

Velier Caroni 1982 Heavy 23 YO (1982 – 2005) 77.3% | Caroni 1985 Heavy 20 YO (1985 – 2005) 75.5% | Caroni 1996 Heavy 20 YO (1996-2016)(Cask R3721) Legend” 70.8% | Caroni 1996 Heavy 20 YO (1996-2016)(Cask R3718) Legend” 70.8% | Caroni 1996 “Trilogy” Heavy (1996 – 2016) 70.28% Cadenhead Single Cask Black Rock WIRR 1986-1998 12 YO 73.4%

Cadenhead Single Cask Black Rock WIRR 1986-1998 12 YO 73.4%

Rom Deluxe Jamaicans (Hampden) – R.17 “Rhino” 5th Anniversary Edition 2019-2021 <2 YO 86.2% | R.20 “Springbok” (C<>H) 2020-2022 86% | R.23 “Pronghorn” (C<>H) 2020-2021 < 2YO 86% |

Rom Deluxe Jamaicans (Hampden) – R.17 “Rhino” 5th Anniversary Edition 2019-2021 <2 YO 86.2% | R.20 “Springbok” (C<>H) 2020-2022 86% | R.23 “Pronghorn” (C<>H) 2020-2021 < 2YO 86% |