Nothing demonstrates the fast-moving development of the rumworld more clearly than the emergence of, and appreciation for, white rums, whether called aguardientes, blancs, whites, silvers, platinos, clairins, grogues, charandas, cane spirits or blancos. So no, I am not referring to the anonymous 40% lightly aged and filtered whites of the American cocktail circuit, where the objective is to hide the rum in the mix (Lamb’s, Bacardi and various forgettable blancos are examples of the type) as if embarrassed to even mention its presence. No, I refer to high proofed, often unaged belters that have enormous taste chops and can wake up a dead stick.

There are several reasons for the emergence of these rums as a major branch of the Great Rum Tree in their own right. For one they speak to the desire of younger audiences for an authentic experience with the terroire of the spirit. It’s not always possible to tell from an aged rum where it hails from unless it’s Jamaica, Guyana or somewhere else with a clearly recognizable profile — by contrast, one is rarely in doubt about the difference between an agricole rhum, a grogue, a clairin, a kokuto shochu or a charanda.

But more than that, white rums are being seen as among the best value for money rums available, because not only are they true purveyors of terroire – they have, after all, not been touched by either barrels’ influence or additives of any kind — but years of ageing are not part of the cost structure. We have been conditioned for years to believe that “older is better” and pay huge sums of money for rums aged three decades or more (or less) – and the entire time, these flavourful rums so representative of their source, which have now gotten to the stage of being good enough to sip or mix, have been quietly developing. They are cheaper, they provide new up and coming distilleries with useful initial cash flow, and are an absolute riot to have for the first time. If there’s a theme at all in this third list of white rums, it’s the emergence of small non-tropical distilleries’ small batch, pot still, unaged whites at ever increasing proof points, demonstrating uniqueness and distinctiveness and inventiveness.

Hold on to your hats, then, because while it’s sure to be a bumpy ride, it’s equally certain we won’t be bored or unhappy, and that’s something we need more of in these troubled times.

Renegade’s Pre-Cask releases (Grenada)

Renegade’s Pre-Cask releases (Grenada)

Years ago I wrote the company profile of Renegade, when they were an early, unappreciated indie bottler ahead of their time. They folded their tents in 2012 but Mark Reynier kept the name, and went on to found a new distillery on Grenada. Not content to wait until his rums aged properly he released five unaged white varietals to showcase what terroire meant. They are all lovely rums, and they prove that terroire and parcellaire really have solid meanings, because each of these rums is completely distinct from every other.

Killik Handcrafted Silver Overproof White (Australia)

Killik Handcrafted Silver Overproof White (Australia)

Killik is one of the New Australian rum companies about which we know far too little and get not enough. It’s hard to say whether their rums will make it to the European or American audiences any time soon: if any single one of them ever does, I hope it’ll be this one. Killik messes around with a hogo-centric approach to their rums and the results are to be seen in all their glory in this almost unknown unaged white rum. (NB Honourable mention should also be made of Winding Road Distillery’s white “Virgin Cane” rum, which was also very good)

Clairin Sonson (Haiti)

Clairin Sonson (Haiti)

Nothing much need be said about this rum, because it’s released by Velier and given all the attention attendant upon that house. For those who don’t know (and want to), it’s made from syrup, not pure cane juice; derives from a non-hybridized varietal of sugar cane called Madam Meuze, juice from which is also part of the clairin Benevolence blend; wild yeast fermentation, run through a pot still, bottled without ageing at 53.2%. What you get from all that is a low key rhum, quite tasty and one to add to the shelf of its four siblings.

Barikenn Montebello 81.6º (France-Guadeloupe)

Barikenn Montebello 81.6º (France-Guadeloupe)

Barikenn is a small French independent out of Brittany that is of relatively recent vintage, having been founded “only” in 2019 by Nicholas Marx, who followed the route taken by another Breton bottler, L’Esprit: slow and easy, small outturns, just a few, and high quality every time. A WP and a Foursquare were first, followed by this massive codpiece of a rum from Guadeloupe at a whopping 81.6%. How it maintains a flavour profile at that strength – and it does, a very good one – is one of life’s enduring mysteries.

Saint James Brut de Colonne “Bio” 74.2% (Martinique)

Saint James Brut de Colonne “Bio” 74.2% (Martinique)

The high water mark for Saint James’s blancs will always, for me, be the Coeur de Chauffe pot still unaged white. Yet for me to dismiss the Brut de Colonne would be foolish because it’s a parcellaire rhum, issued with serious proofage, and best of all, it’s wonderful either by itself, or in a mix. Distinctive, unique, flavourful and useful, it’s a tough act for this old house to beat.

Pere Labat Brut de Colonne 70.7º (Guadeloupe)

Pere Labat Brut de Colonne 70.7º (Guadeloupe)

There is nothing particularly special about this unaged blanc from Marie Galante: it’s not a bio, a parcellaire or some fancy experimental, and in fact, the 40º, 50º and 59º blancs also deliver similar profiles…with somewhat less power, to be sure. Yet the sheer intensity of what is provided here makes this, the strongest rum in the company’s arsenal, impossible to ignore completely and to be honest, I liked it quite a bit.

Engenhos do Norte Branca Rum Fire 60º Agricola (Madeira)

Engenhos do Norte Branca Rum Fire 60º Agricola (Madeira)

Slowly but surely Madeiran rums are becoming De Next Big Ting within the rum world and maybe it’s just poor word of mouth that’s keeping them from being more appreciated. The “Branca” at 60% may be Engenhos do Norte’s strongest commercial offering (the word means “The White One”) and it is their own bottling, not something they passed on to either That Boutique-y Rum Co. or Rum Nation. It’s distilled on a column barbet still as far as I know, and it’s quite a tasty treat.

N4021

El Destilado Wild Fermented Oaxaca Rum (Mexico/UK)

El Destilado is a small UK bottler whose signature limited edition rums are all from Mexico (mostly from Oaxaca) and are really charandas in all but name (thought unless from Michoacan and covered by the Designation of Origin, they’re not). This rum is from 100% cane juice, natural five-day fermentation, 8-plate column still distillation and trapped with zero ageing. The terroire shines through this thing, and while some flavours will appear strange, wild and near-untamed, well, I made similar comments on the clairin Sajous back in 2014, and look how well that turned out. I buy every rum this company makes on principle, because I think when the dust settles, we’ll never see their like again.

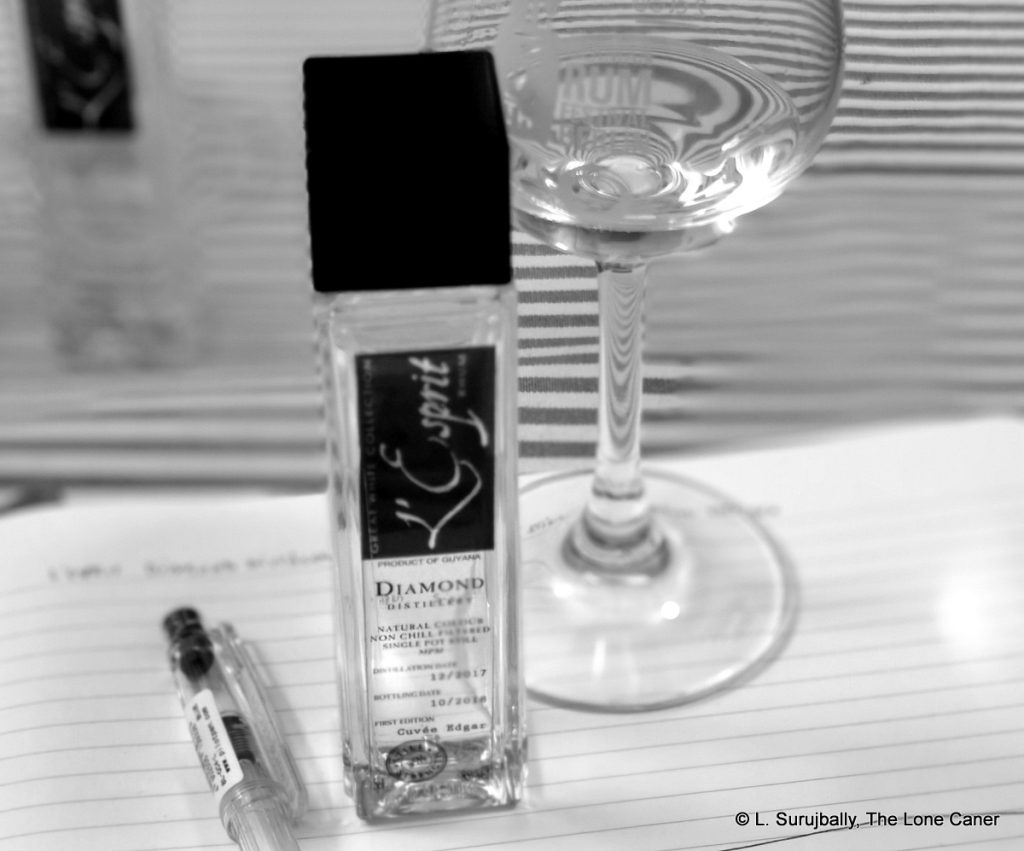

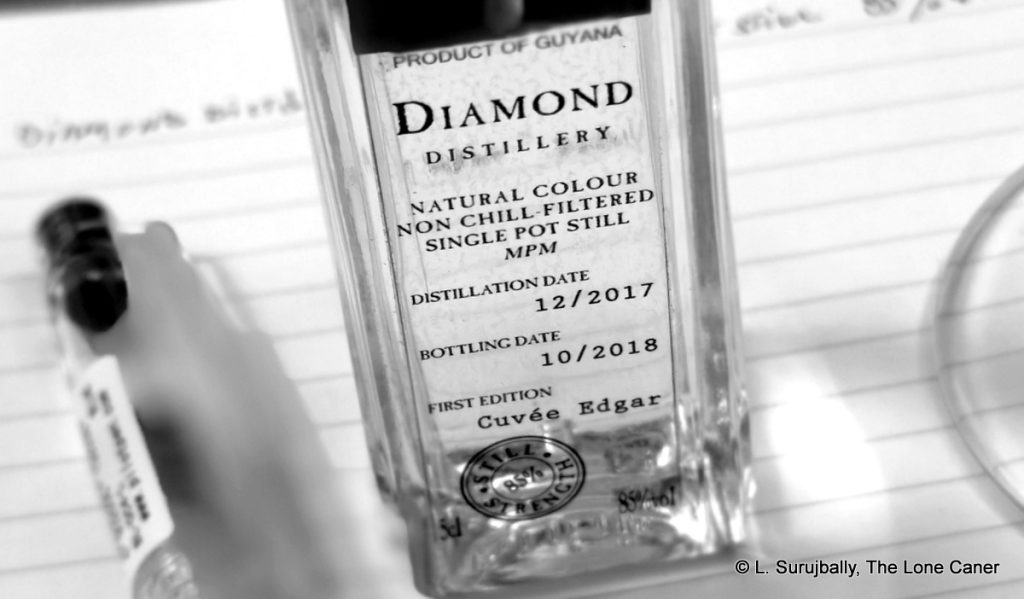

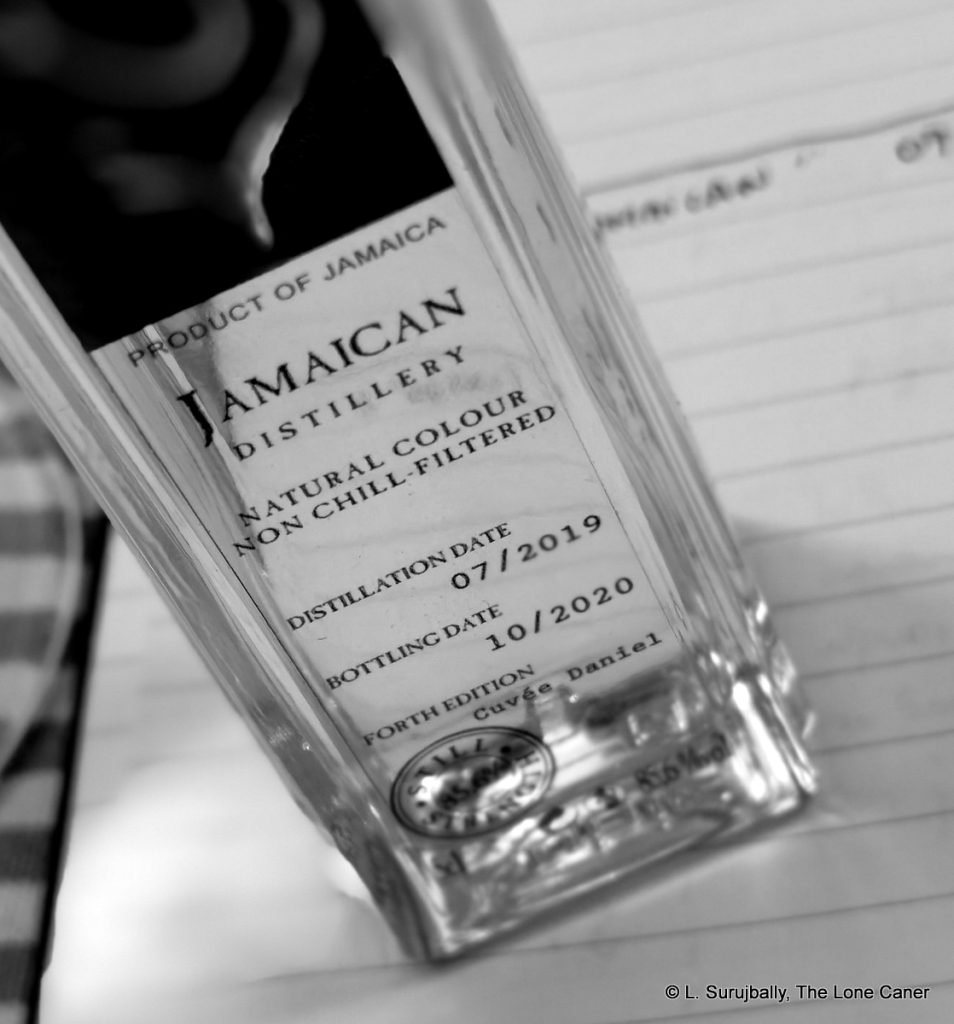

L’Esprit Jamaican “Still Strength” White Rum (France-Jamaica)

L’Esprit Jamaican “Still Strength” White Rum (France-Jamaica)

L’Esprit is one of a handful of unappreciated European indies whose reputation should be greater. They still make extraordinary barrel selections of aged rums, yet the occasional unaged whites they produce may be even more amazing. On my last list I mentioned their “still strength” 85% Port Mourant white, and of the next batch, the 85.6% Jamaican white released in 2020 is equally worthy of acclaim. If you want to see a white that channels shock and awe in equal measure, you may have found it here.

St. Nicholas Abbey Overproof White (Barbados)

St. Nicholas Abbey Overproof White (Barbados)

Who would have thought that the conservative Barbadian Little Distillery That Could could escape its traditions? For most of their releases it’s been ever increasing ages and all at living room strength, and then somebody decided to cast caution to the winds, step on the gas and dropped this 60% beater of an unaged white on us. Holy Full Proof, Batman. It’s fiery, it’s spicy and tasty and aromatic, all at the same time

Foursquare LFT White (Barbados)

Foursquare LFT White (Barbados)

Few rums are or have been more eagerly anticipated than Foursquare’s various ECS rums or the Collaborations with Velier. Yet those were and are variations on a theme: well known and much loved to be sure, but not completely original either. This one, now – this one is cut from wholly new cloth for the distillery, has the potential to take the company in a whole new direction, and the best part is, it’s really kind of fantastic: a high-ester long-fermentation style rum from juice that may just cause a few puckered…er…brows, over in the French islands. And, maybe, South Africa. As all the 2022 UK and Paris rum fests are now over, look for reviews of this thing to come soon from all the usual suspects. Me, I think it’s great.

William Hinton 69% White Agricole (Madeira)

William Hinton 69% White Agricole (Madeira)

A year or so back, I wrote about a white Madeiran rum from William Hinton (Engenho Novo) at the usual inoffensive 40% and gave it a dismissive “it’s a rum” rating of 75 points. It didn’t impress me much. Side by side with that was another review: of the overproof white at 69%. Both were column still cane juice agricoles, but the difference was night and day – the stronger version is completely impressive on all levels and while it’s made for mixing, I’d enjoy it fine exactly as it is. (The difference is probably because the 69% edition is not aged and has a 2-3 days’ fermentation time, unlike the 40%’s 24 hrs and a couple of years’ ageing and subsequent filtration).

Montanya Platino (USA)

Montanya Platino (USA)

Aside from maybe a double handful of serious distilleries, American rums rarely get much appreciation or respect, and with good reason — they keep trying to make whisky and see rums as a “filler” spirit (if even that), and the results often reflect that indifference. Not so Montanya, Karen Hoskins’ little outfit in Colorado. There’s all sorts of promising stuff going on there and this white rum is one of them – it’s one of the few white rums out of the USA that does not try to copy Bacardi, take cheap shortcuts, or, at end, disappoint.

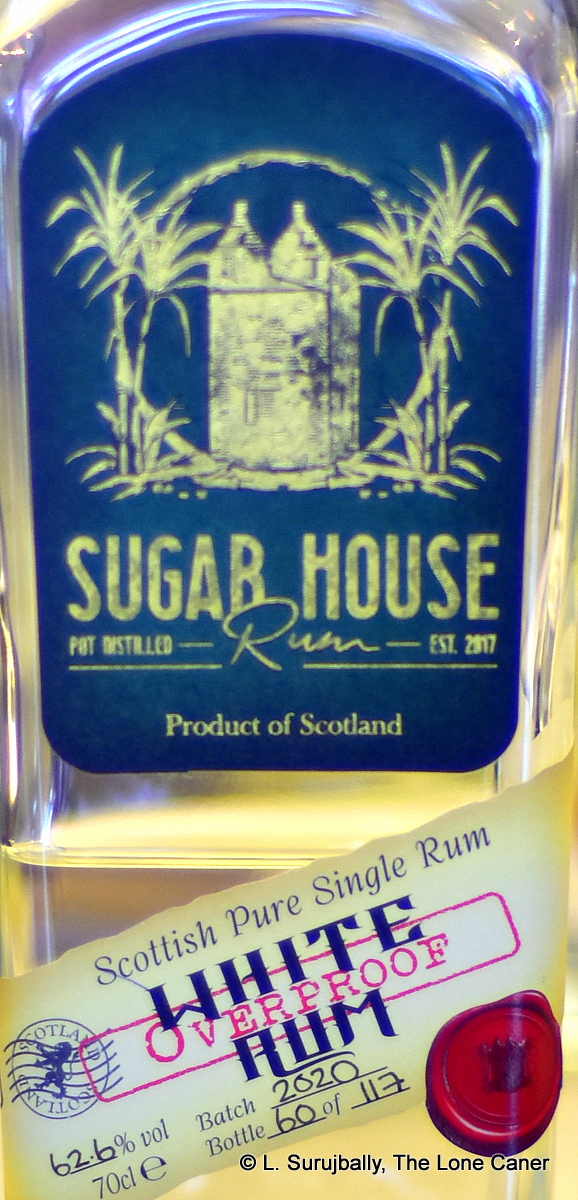

Sugar House White Overproof Rum (UK)

Sugar House White Overproof Rum (UK)

The New Scots are coming, and they aren’t messing around. Sugar House demonstrates that it’s not necessary to have a ginormous industrial still, age your rum up to yinyang in barrels blessed by the Pope, be in the tropics or have a cool pirate theme to be completely, totally awesome. I have little interest in their spiced rums, “scotch bonnet” rums or the coffee infused varietals, and even the standard white they make is not in this one’s league. The overproof though….in a word, fantastic. It has so many flavour notes I’m in danger of running out of words.

Islay Rum Co. “Geal” Pure Single Rum (UK)

Islay Rum Co. “Geal” Pure Single Rum (UK)

The British Invasion is getting serious when an island renowned for its whisky distilleries can allow a rum distillery to be constructed (in Port Ellen, forsooth!). I was able to try the 2022 Inaugural Release of a 45% pot still unaged white rum, which is made with a 5-7 day fermentation period and uses dunder. The results, while not spectacular, channel Jamaica so well that it cannot be ignored, and I wouldn’t want to. Are we sure this is made in Scotland?

J. Gow “Culverin” Unaged White Rum (UK)

J. Gow “Culverin” Unaged White Rum (UK)

J. (for “John”) Gow Distillery is located on what is likely the smallest rum producing island in the world, up in the Orkneys in northern Scotland, on a 0.15 square mile island called Lamb Holm, where it is rumoured, cane does not grow well. Armed with a 2000-litre pot still they produce a series of lightly aged rums with evocative names, all at around standard strength. The “Culverin” unaged white I tried at TWE Rum Show in 2022 really was a quiet little stunner. Bottled at 50% it channelled dusty, woody, briny, molasses and kimchi notes that reminded me of unaged Port Mourant rums. Note: to be honest the limited (171-bottle and sold-out) edition of the 1st Wild Yeast white rum they did back in March 2022 was even better, but I’d prefer to have this list represent rums you can actually get.

Papa Rouyo Rhum Agricole de Terroire (Guadeloupe)

Papa Rouyo Rhum Agricole de Terroire (Guadeloupe)

Papa Rouyo has been quietly available in France for about a year, and perhaps it’s 2022 that was their coming out party. A new microdistillery in Le Moule on Guadeloupe — which puts them right by Damoiseau — they operate a couple of charentais pot stills to make cane juice rhums. Some are aged, some are single cask, some are taken by indies like Velier for the HV line. But it’s the pair of lightly aged (120 days and 450 days) almost-whites that I include here, because their double distillation and R579 Red Cane varietal makes for two stunning rhums. The aromas and tastes almost explode in the nose and mouth, and while adhering to the general agricole profile, go off in joyous directions of their own at the same time.

La Favorite “La Digue” and “Riviere Bel’Air” (Martinique) Rhum Agricole Blanc (Martinique)

La Favorite “La Digue” and “Riviere Bel’Air” (Martinique) Rhum Agricole Blanc (Martinique)

Another pair that are tough to separate: 52% and 53% respectively, parcellaire rhums, limited outturns, AOC specs, 2018 harvest, monovarietal canes, unaged…few rhums pack such a series of plot points to their production details. What comes out at the other end is delicious: sweet, herbal, spicy, citrus, vegetal, fruity, tart….I could go on, but the bottom line is that this pair of rhums, either or both, shows why parcellaires deserve attention.

Another pair that are tough to separate: 52% and 53% respectively, parcellaire rhums, limited outturns, AOC specs, 2018 harvest, monovarietal canes, unaged…few rhums pack such a series of plot points to their production details. What comes out at the other end is delicious: sweet, herbal, spicy, citrus, vegetal, fruity, tart….I could go on, but the bottom line is that this pair of rhums, either or both, shows why parcellaires deserve attention.

Chalong Bay High Proof White Rum (Thailand)

Chalong Bay High Proof White Rum (Thailand)

The Thai cane juice rum from Chalong Bay should didn’t make the cut for either of my two initial lists…probably because I had only tried the original 40% white and that was decent, just not terrific. Things got dialled up quite a bit with the high proof rum, though. The 57% rhum nosed well, tasted well and was an all round winner for me. While I liked it, it’s hard to tell whether such a product would sell in its home country where softer and sweeter profiles are more common, so the jury is out on whether it continues to be made, and if for export only or not.

J. Bally Unaged White Rhum 55% (Martinique)

J. Bally Unaged White Rhum 55% (Martinique)

Bally has been on the list before with their more mainstream 50% rhum blanc, yet the 55% unaged white is so good, it even eclipses the untrammelled quality of the regular offering (which was surely no slouch either). I can’t say what makes the extra five points of proof so intrinsically delicious, only that somehow it exceeds its origins. I really loved it and went back to the bottle several times to filch some more.

Habitation Velier Distillerie De Port Au Prince Double Distilled White Rhum (Haiti)

Habitation Velier Distillerie De Port Au Prince Double Distilled White Rhum (Haiti)

Given it was distilled in 2021 (twice) but not seen in public until 2022 (and even then the label seemed incomplete), I’m unsure whether it’s been aged or rested. From the taste, my money is on the latter. Initial distillation in the Providence Distillery located in Port-au-Prince, the capital, with crystalline cane syrup coming from Saint-Michel-de-l’Attalaye (also home of Benevolence, Sajous and Le Rocher). It channels all the agricole hits — brine, fresh fruit, cane, honey and a smorgasbord of a lot else; I found it rather more elegant than the punch of, say, the Sajous.. It’s a great entry into the HV series and just keeps getting better as you taste it.

Summing Up

Looking at this list, it’s clear that the epicentre of such rhums remains for the most part in the Caribbean (and I’ve excluded a few other really good rhums from there to keep the list from ballooning too far and showcase other regions). There are still many interesting rums to be had from other countries and continents, of course, and I think that the areas to keep an eye on are Asia and Africa (South Africa. Ghana, Senegal and Cameroon specifically, for now).

Another interesting trend these whites suggest, is the emergence of micro-distilleries in locations like the UK, which are outside the usual tropical haunts of enthusiast-driven operations. Since GIs, terroire and cane juice are not the main focus, they can buy molasses from wherever, and just go from there – so what’s surprising is how good so many of them are.

Lastly, it’s good to see the 40% limitation is being dispensed with across the board. Whites are being issued at any strength suitable to their character, and although sometimes I think distilleries take it to extremes with the “still strength” releases (Rom Deluxe’s DR 93.6% white rum is the poster boy for this in action), it’s way better than the anonymous blah I grew up with and which still dominates too many bars I’ve been cordially escorted (= “thrown out”) of.

So that’s it for now. Until List #4 comes out, try these and enjoy the ride.

Note: Previous lists of great white rums are here (#1) and here (#2).

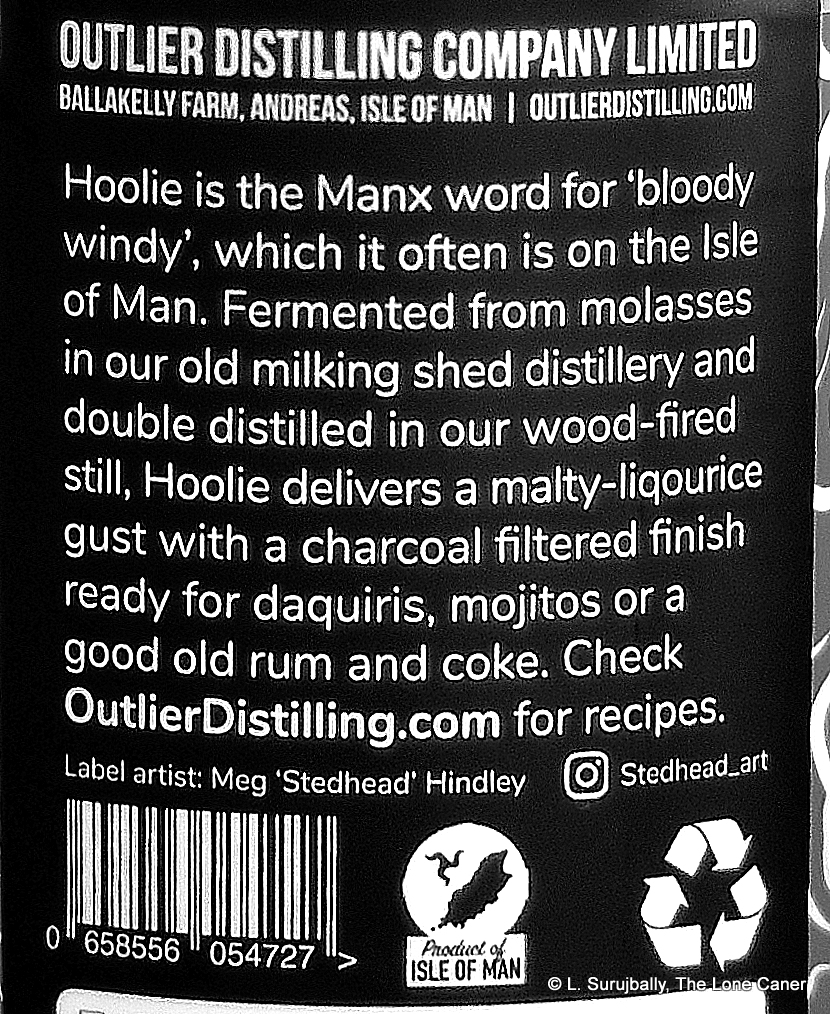

The Coastal Cane is a molasses based spirit, from molasses fermented for ten days and then run twice through “Rocky” the double retort. No ageing, no additions, no filtering, just reduction down to standard strength of 40% ABV.

The Coastal Cane is a molasses based spirit, from molasses fermented for ten days and then run twice through “Rocky” the double retort. No ageing, no additions, no filtering, just reduction down to standard strength of 40% ABV.