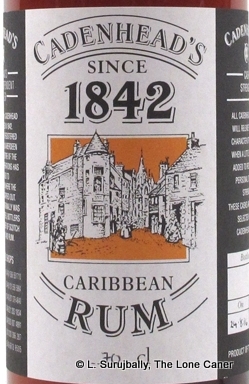

Photo used courtesy of /u/Franholio from his Reddit post

Every now and then a reviewer has to bite the bullet and admit that he’s got a rum to write about which is so peculiar and so rare and so unknown (though not necessarily so good) that few will have ever heard of it, fewer will ever get it, and it’s likely that nobody will ever care since the tasting notes are pointless. Cadenhead’s 2016 release of the Caribbean Rum blend (unofficially named “Living Cask” or “1842” because of the number on the label) is one of these.

Why is it so unknown? Well, because it’s rare, for one — of this edition, only 28 bottles were released back in 2016, and how this could happen with what is supposedly a mix of many barrels? For comparison, the Velier Albion 1989 had 108 bottles, and it wasn’t a blend. Only the Spirits of Old Man Uitvlugt had this small an outturn, if you discount the Caputo 1973 which had a single bottle. It’s been seen the sum total of one time at auction, also in 2016 and sold for £85 (in that same auction a Cadenhead from the cask series, the TMAH, sold for £116, as a comparator).

But a gent called Franholio on Reddit, supplemented by WildOscar66, and then a 2015 review by the FRP on another variant explained it: this is a sort of Scottish solera, or an infinity cask. It is a blend of assorted rums, in this case supposedly mostly Demeraras in the 8-10 YO range, though these are never defined and could as easily be anything else. These are dunked into any one of several quarter-casks (about 50 liters) which are kept in Cadenhead shops in Edinburgh and London, constantly drawn off to bottle and then when it hits halfway down, is refilled from a bit left over from whatever IB cask they’re bottling. What this means is that it is not only a “living cask” but that the chances of your bottle being the same as mine is small – I’ve picked up references to several of these, and they all have different bottling years, strengths, sizes and tasting notes.

But a gent called Franholio on Reddit, supplemented by WildOscar66, and then a 2015 review by the FRP on another variant explained it: this is a sort of Scottish solera, or an infinity cask. It is a blend of assorted rums, in this case supposedly mostly Demeraras in the 8-10 YO range, though these are never defined and could as easily be anything else. These are dunked into any one of several quarter-casks (about 50 liters) which are kept in Cadenhead shops in Edinburgh and London, constantly drawn off to bottle and then when it hits halfway down, is refilled from a bit left over from whatever IB cask they’re bottling. What this means is that it is not only a “living cask” but that the chances of your bottle being the same as mine is small – I’ve picked up references to several of these, and they all have different bottling years, strengths, sizes and tasting notes.

That doesn’t invalidate the skill that’s used to add components to the casks, however – the rum is not a mess or a completely mish-mashed blend of batsh*t crazy by any means. Consider first the nose: even if I hadn’t known there was some Demerara in there I would have suspected it. It smelled of well polished leather, dark dried fruits, smoke and cardamom, remarkably approachable and well tamed for the strength of 60.6%. It melded florals, fruitiness and brine well, yet always maintained a musty and hay-like background to the aromas. Only after opening up were more traditional notes discerned: molasses, caramel, burnt sugar, toffee, toblerone, a little coffee and a trace of licorice, not too strong.

I would not go so far as to say this was a clearly evident heritage (wooden) still rum, or even that there was plenty of such a beast inside, because taste-wise, I felt the rum faltering under the weight of so many bits and pieces trying to make nice with each other. Salty caramel, molasses, prunes and licorice were there, though faintly, which spoke to the dilution with other less identifiable rums; some dark and sweet fruits, vanilla, a hint of oaken bitterness, more smoke, more leather. The coffee and chocolate returned after a while. Overall, it wasn’t really that interesting here, and while the finish was long and languorous, it was mostly a rehash of what came before – a rich black cake with loads of chopped fruits, drizzled with caramel syrup, to which has been added a hint of cinnamon and cardamom and some vanilla flavoured whipped cream.

This Cadenhead is a completely fine rum, and I’m impressed as all get out that a quarter-cask solera-style rum – one of several in shops that have better things to do than micromanage small infinity barrels – is as good as it is. What I’m not getting is distinctiveness or something particularly unique, unlike those “lettered” single barrel releases for which Cadenhead is perhaps more renowned. I might have scored it more enthusiastically had that been the case.

I believe that the process of developing any blend is to smoothen out widely variant valleys and peaks of taste into something that is both tasty and unique in its own way, without losing the interest of the drinker by making something overly blah. Here, I think that the rum’s strength carries it further than the profile alone could had it been weaker: and that although that profile is reasonably complex and has a nice texture, sold at a price that many have commented on as being pretty good…it is ultimately not really as rewarding an experience as it might have been with more focus, on fewer elements.

(#797)(84/100)

Other notes

- While the review ends on a down note, I did actually enjoy it, and that’s why I endorse going to any of Cadenhead’s shops that have one of these casks, and tasting a few.

- Nicolai Wachmann, one of my rum tooth fairies out of Denmark, kindly passed along the sample.

In an ever more competitive market – and that includes French island agricoles – every chance is used to create a niche that can be exploited with first-mover advantages. Some of the agricole makers, I’ve been told, chafe under the strict limitations of the AOC which they privately complain limits their innovation, but I chose to doubt this: not only there some amazing rhums coming out the French West Indies within the appellation, but they are completely free to move outside it (as

In an ever more competitive market – and that includes French island agricoles – every chance is used to create a niche that can be exploited with first-mover advantages. Some of the agricole makers, I’ve been told, chafe under the strict limitations of the AOC which they privately complain limits their innovation, but I chose to doubt this: not only there some amazing rhums coming out the French West Indies within the appellation, but they are completely free to move outside it (as

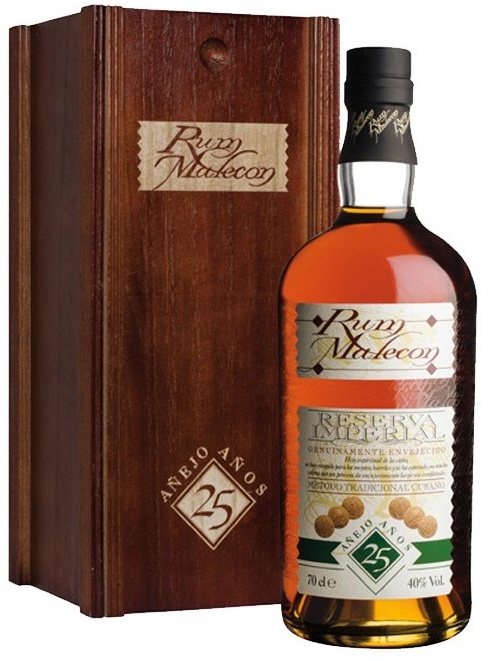

We’ve been here before. We’ve tried a rum with this name, researched its background, been baffled by its opaqueness, made our displeasure known, then yawned and shook our heads and moved on. And still the issues that that one raised, remain. The Malecon Reserva Imperial 25 year old suffers from many of the same defects of its

We’ve been here before. We’ve tried a rum with this name, researched its background, been baffled by its opaqueness, made our displeasure known, then yawned and shook our heads and moved on. And still the issues that that one raised, remain. The Malecon Reserva Imperial 25 year old suffers from many of the same defects of its  The palate is similarly soft and similarly straightforward. It’s got more chocolate milk and and perhaps a touch of coffee grounds. A smidgen, barely a smidgen of oak and citrus, a sly taste of tangerines; it’s not very sweet (which is a plus) and sports some brine and Turkish olives and a touch of slight bitterness, which I’m going be generous and say is an oak influence that saves it from being just blah. Finish is okay I guess. Gone too quickly of course, no surprise at 40% ABV and leaving at best the sense of some black tea with too much condensed milk in it, that doesn’t entirely hide the fact that it’s too bitter.

The palate is similarly soft and similarly straightforward. It’s got more chocolate milk and and perhaps a touch of coffee grounds. A smidgen, barely a smidgen of oak and citrus, a sly taste of tangerines; it’s not very sweet (which is a plus) and sports some brine and Turkish olives and a touch of slight bitterness, which I’m going be generous and say is an oak influence that saves it from being just blah. Finish is okay I guess. Gone too quickly of course, no surprise at 40% ABV and leaving at best the sense of some black tea with too much condensed milk in it, that doesn’t entirely hide the fact that it’s too bitter.

It gets no better when tasted. It’s very darkly sweet, liqueur-like, giving up flavours of prunes and stewed apples (again); dates; peaches in syrup, yes, more syrup, vanilla and a touch of cocoa. Honey, Cointreau, and both cloying and wispy at the same time, with a last gasp of caramel and toffee. The finish is thankfully short, sweet, thin, faint, nothing new except maybe some creme brulee. It’s a rum that, in spite of its big number and heroic Jose Marti visage screams neither quality or complexity. Mostly it yawns “boring!”

It gets no better when tasted. It’s very darkly sweet, liqueur-like, giving up flavours of prunes and stewed apples (again); dates; peaches in syrup, yes, more syrup, vanilla and a touch of cocoa. Honey, Cointreau, and both cloying and wispy at the same time, with a last gasp of caramel and toffee. The finish is thankfully short, sweet, thin, faint, nothing new except maybe some creme brulee. It’s a rum that, in spite of its big number and heroic Jose Marti visage screams neither quality or complexity. Mostly it yawns “boring!”

The palate was thick, rich and sweet, even in comparison the the 3YO which showed no modesty with such aspects itself but while stronger, had also been paradoxically easier. Here we were regaled with bananas, cherries in syrup, brown sugar, and a sort of smorgasbord of fruitiness – some tart, some just soft and mushy – and creaminess of greek yogurt sprinkled with cinnamon and cloves. Disappointingly, the finish did nothing much except lock the door and walk off, throwing a few notes of cloves, sugar, cherries, peaches and syrup behind. Not a stellar finish after the intriguing beginning.

The palate was thick, rich and sweet, even in comparison the the 3YO which showed no modesty with such aspects itself but while stronger, had also been paradoxically easier. Here we were regaled with bananas, cherries in syrup, brown sugar, and a sort of smorgasbord of fruitiness – some tart, some just soft and mushy – and creaminess of greek yogurt sprinkled with cinnamon and cloves. Disappointingly, the finish did nothing much except lock the door and walk off, throwing a few notes of cloves, sugar, cherries, peaches and syrup behind. Not a stellar finish after the intriguing beginning. Hampden gets so many kudos these days from its relationship with

Hampden gets so many kudos these days from its relationship with  The rum displays all the attributes that made the estate’s name after 2016 when they started supplying their rums to others and began bottling their own. It’s a rum that’s astonishingly stuffed with tastes from all over the map, not always in harmony but in a sort of cheerful screaming chaos that shouldn’t work…except that it does. More sensory impressions are expended here than in any rum of recent memory (and I remember

The rum displays all the attributes that made the estate’s name after 2016 when they started supplying their rums to others and began bottling their own. It’s a rum that’s astonishingly stuffed with tastes from all over the map, not always in harmony but in a sort of cheerful screaming chaos that shouldn’t work…except that it does. More sensory impressions are expended here than in any rum of recent memory (and I remember

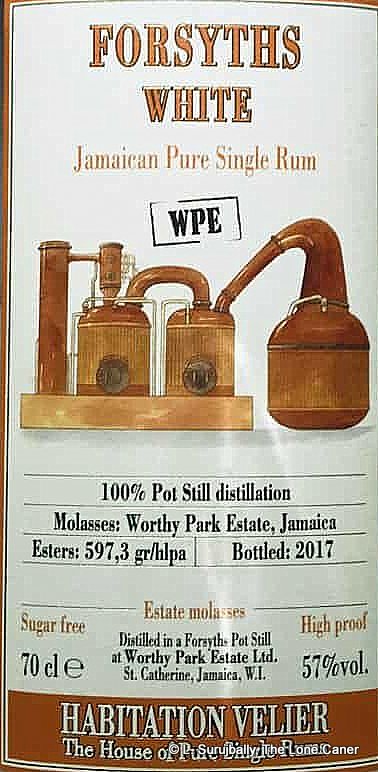

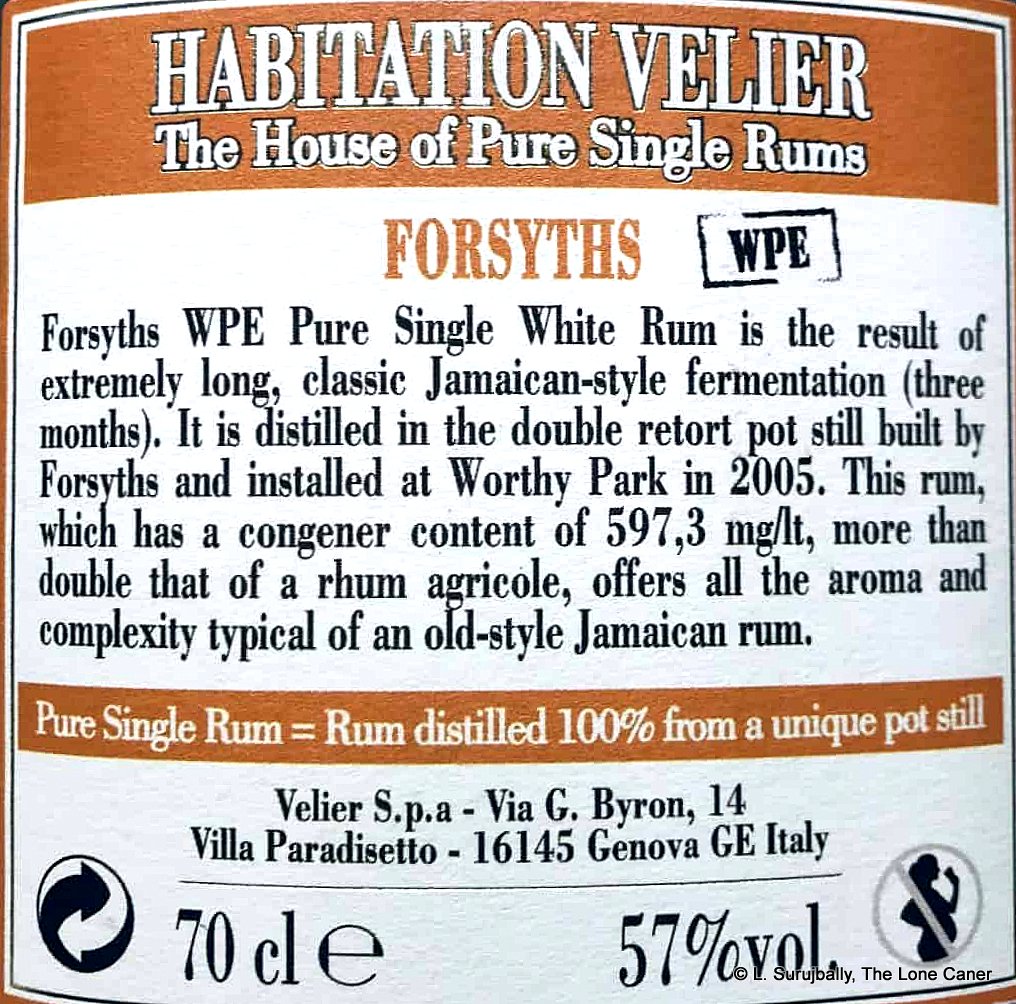

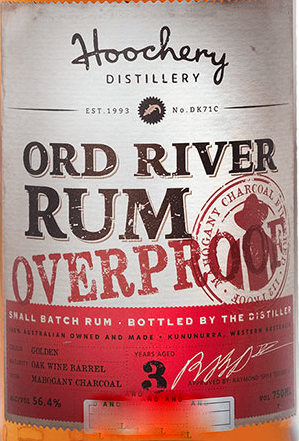

In spite of the high ABV, which lends a fair amount of initial sharpness and heat to the tongue until it burns away and settles down, it’s actually not that fierce. It becomes almost delicate, and there’s a nice vein of fruity sweetness running through, which enhances the flavours of apples, cider, green grapes, citrus, coconut, vanilla, and candied oranges. There’s also some of that polish and acetone remaining, neatly dampened by caramel and brown sugar, all balancing off well against each other. It retains that delicacy to the finish line and stays well behaved: a touch sweet throughout, with caramel (a bit much), vanilla, fruits, grapes, raisins, citrus, blancmange…not bad at all.

In spite of the high ABV, which lends a fair amount of initial sharpness and heat to the tongue until it burns away and settles down, it’s actually not that fierce. It becomes almost delicate, and there’s a nice vein of fruity sweetness running through, which enhances the flavours of apples, cider, green grapes, citrus, coconut, vanilla, and candied oranges. There’s also some of that polish and acetone remaining, neatly dampened by caramel and brown sugar, all balancing off well against each other. It retains that delicacy to the finish line and stays well behaved: a touch sweet throughout, with caramel (a bit much), vanilla, fruits, grapes, raisins, citrus, blancmange…not bad at all.

Or so the story-teller in me supposes. Because all jokes and anecdotes aside, what this is, is a rum made to order.

Or so the story-teller in me supposes. Because all jokes and anecdotes aside, what this is, is a rum made to order.

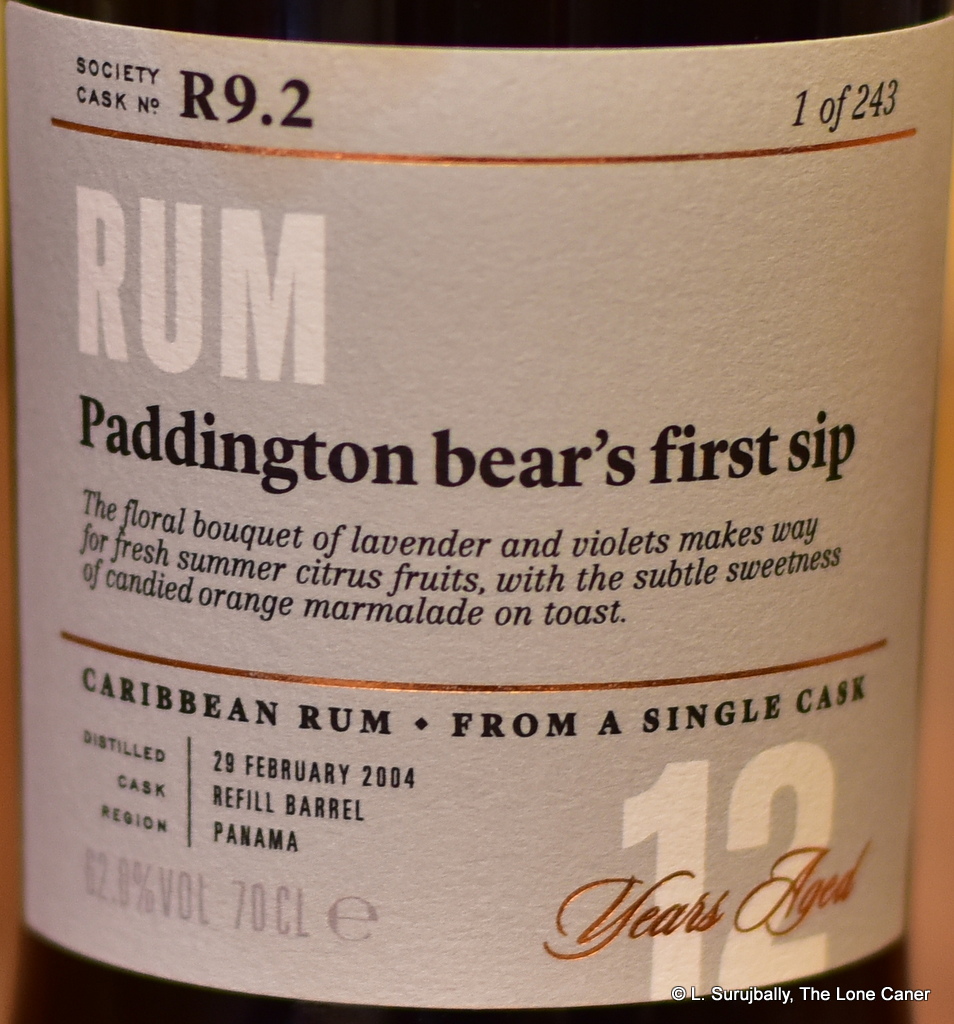

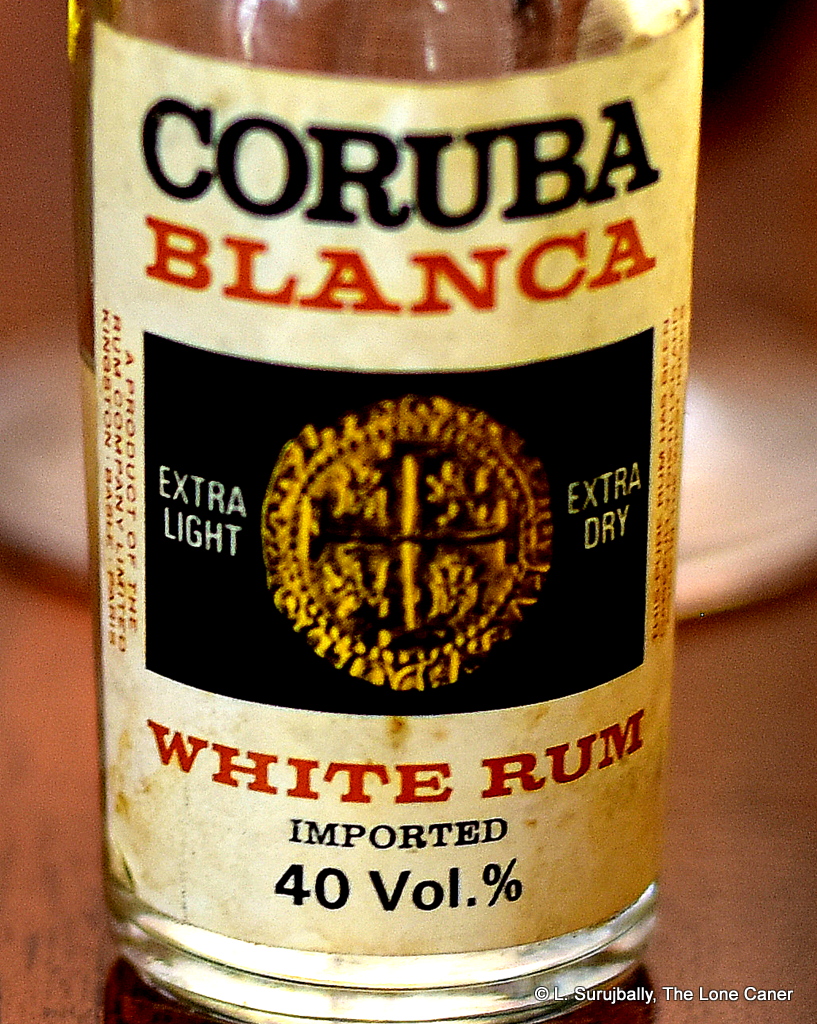

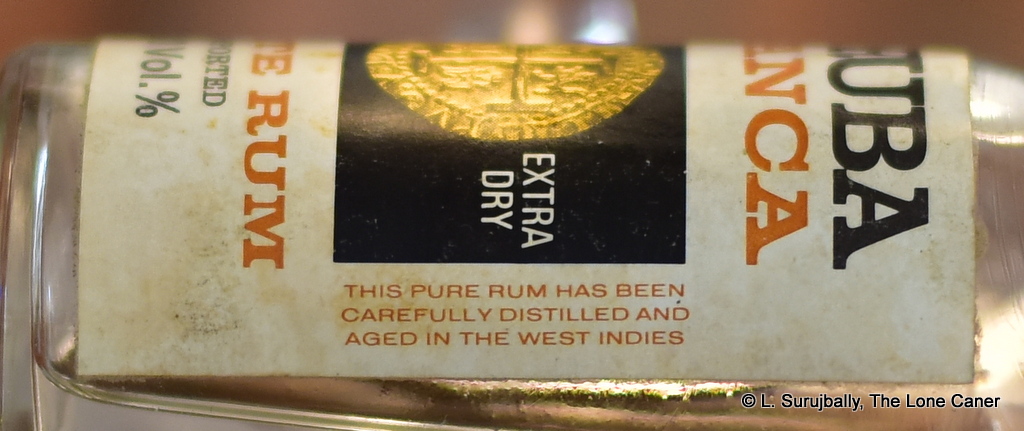

The nose begins with metallic, ashy notes right away, damp cardboard in a long-abandoned, leaky musty house. Thankfully this peculiar aroma doesn’t hang around, but morphs into a sort of soya-salt veggie soup vibe, which in turn gets muskier and sweeter over time; it releases notes of bananas and molasses and syrup, before gradually lightening and becoming – surprisingly enough – rather crisp. White fruits emerge – unripe pears and guavas, green apples, gooseberries, grapes. What’s really surprising is the way this all transforms over a period of ten minutes or so from one nasal profile to another. It’s not usual, but it is noteworthy.

The nose begins with metallic, ashy notes right away, damp cardboard in a long-abandoned, leaky musty house. Thankfully this peculiar aroma doesn’t hang around, but morphs into a sort of soya-salt veggie soup vibe, which in turn gets muskier and sweeter over time; it releases notes of bananas and molasses and syrup, before gradually lightening and becoming – surprisingly enough – rather crisp. White fruits emerge – unripe pears and guavas, green apples, gooseberries, grapes. What’s really surprising is the way this all transforms over a period of ten minutes or so from one nasal profile to another. It’s not usual, but it is noteworthy. Rumaniacs Review #122 | 0785

Rumaniacs Review #122 | 0785

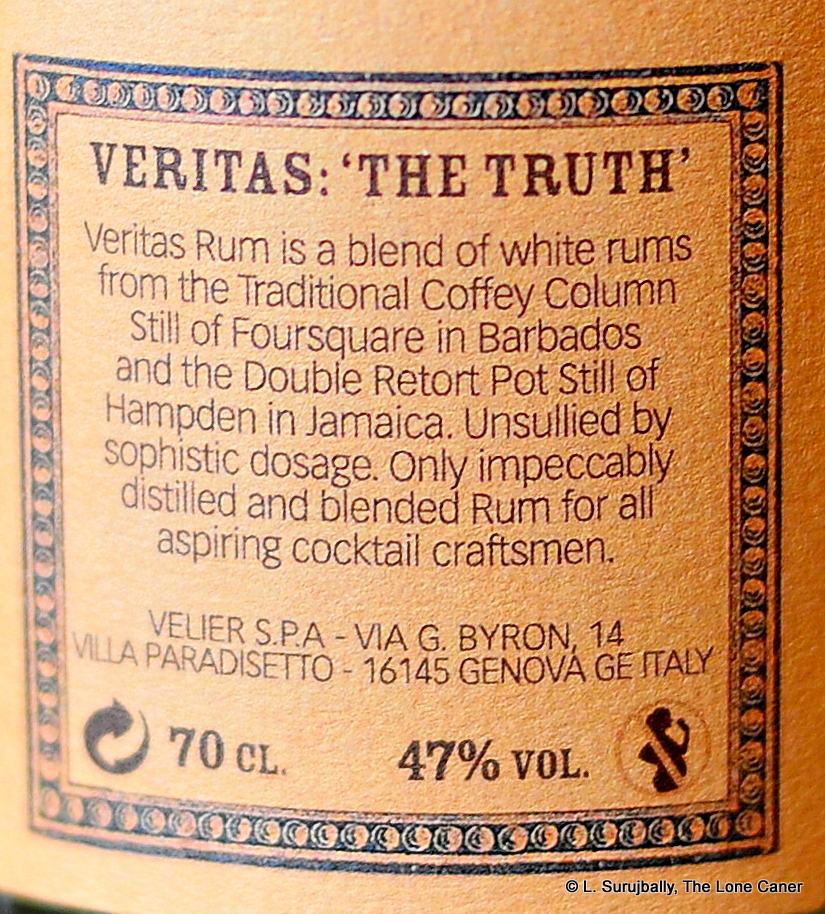

When it really comes down to it, the only thing I didn’t care for is the name. It’s not that I wanted to see “Jamados” or “Bamaica” on a label (one shudders at the mere idea) but I thought “Veritas” was just being a little too hamfisted with respect to taking a jab at Plantation in the ongoing feud with Maison Ferrand (the statement of “unsullied by sophistic dosage” pointed there). As it turned out, my opinion was not entirely justified, as Richard Seale noted in a comment to to me that… “It was intended to reflect the simple nature of the rum – free of (added) colour, sugar or anything else including at that time even addition from wood. The original idea was for it to be 100% unaged. In the end, when I swapped in aged pot for unaged, it was just markedly better and just ‘worked’ for me in the way the 100% unaged did not.” So for sure there was more than I thought at the back of this title.

When it really comes down to it, the only thing I didn’t care for is the name. It’s not that I wanted to see “Jamados” or “Bamaica” on a label (one shudders at the mere idea) but I thought “Veritas” was just being a little too hamfisted with respect to taking a jab at Plantation in the ongoing feud with Maison Ferrand (the statement of “unsullied by sophistic dosage” pointed there). As it turned out, my opinion was not entirely justified, as Richard Seale noted in a comment to to me that… “It was intended to reflect the simple nature of the rum – free of (added) colour, sugar or anything else including at that time even addition from wood. The original idea was for it to be 100% unaged. In the end, when I swapped in aged pot for unaged, it was just markedly better and just ‘worked’ for me in the way the 100% unaged did not.” So for sure there was more than I thought at the back of this title.

This process provides a tasting profile that reminds me of nothing so much than a slightly addled wooden still-rum from El Dorado: it’s sweet, feels the slightest bit sticky, and has strong notes of dark fruits, red licorice, plums, raisins and an almond chocolate bar gone soft in the heat. There’s other stuff in there as well – some caramel, vanilla, pepper again, light orange peel, but overall the whole thing is not particularly complex, and it ambles easily towards a short and gentle finish of no particular distinction that pretty much displays some dark fruit, caramel, anise and molasses, and that’s about it.

This process provides a tasting profile that reminds me of nothing so much than a slightly addled wooden still-rum from El Dorado: it’s sweet, feels the slightest bit sticky, and has strong notes of dark fruits, red licorice, plums, raisins and an almond chocolate bar gone soft in the heat. There’s other stuff in there as well – some caramel, vanilla, pepper again, light orange peel, but overall the whole thing is not particularly complex, and it ambles easily towards a short and gentle finish of no particular distinction that pretty much displays some dark fruit, caramel, anise and molasses, and that’s about it. So, until we know more, focus on the rum itself. It’s quiet and gentle and some cask strength lovers might say – not without justification – that it’s insipid. It has some good tastes, simple but okay, and hews to a profile with which we’re not entirely unfamiliar. It has a few off notes and a peculiar substrate of something different, which is a good thing. So in the end,

So, until we know more, focus on the rum itself. It’s quiet and gentle and some cask strength lovers might say – not without justification – that it’s insipid. It has some good tastes, simple but okay, and hews to a profile with which we’re not entirely unfamiliar. It has a few off notes and a peculiar substrate of something different, which is a good thing. So in the end,

By the time this rum was released in 2014, things were already slowing down for Velier in its ability to select original, unusual and amazing rums from DDLs warehouses, and of course it’s common knowledge now that 2014 was in fact the last year they did so. The previous chairman, Yesu Persaud, had retired that year and the arrangement with Velier was discontinued as DDL’s new Rare Collection was issued (in early 2016) to supplant them.

By the time this rum was released in 2014, things were already slowing down for Velier in its ability to select original, unusual and amazing rums from DDLs warehouses, and of course it’s common knowledge now that 2014 was in fact the last year they did so. The previous chairman, Yesu Persaud, had retired that year and the arrangement with Velier was discontinued as DDL’s new Rare Collection was issued (in early 2016) to supplant them. The nose had been so stuffed with stuff (so to speak) that the palate had a hard time keeping up. The strength was excellent for what it was, powerful without sharpness, firm without bite. But the whole presented as somewhat more bitter than expected, with the taste of oak chips, of cinchona bark, or the antimalarial pills I had dosed on for my working years in the bush. Thankfully this receded, and gave ground to cumin, coffee, dark chocolate, coca cola, bags of licorice (of course), prunes and burnt sugar (and I

The nose had been so stuffed with stuff (so to speak) that the palate had a hard time keeping up. The strength was excellent for what it was, powerful without sharpness, firm without bite. But the whole presented as somewhat more bitter than expected, with the taste of oak chips, of cinchona bark, or the antimalarial pills I had dosed on for my working years in the bush. Thankfully this receded, and gave ground to cumin, coffee, dark chocolate, coca cola, bags of licorice (of course), prunes and burnt sugar (and I

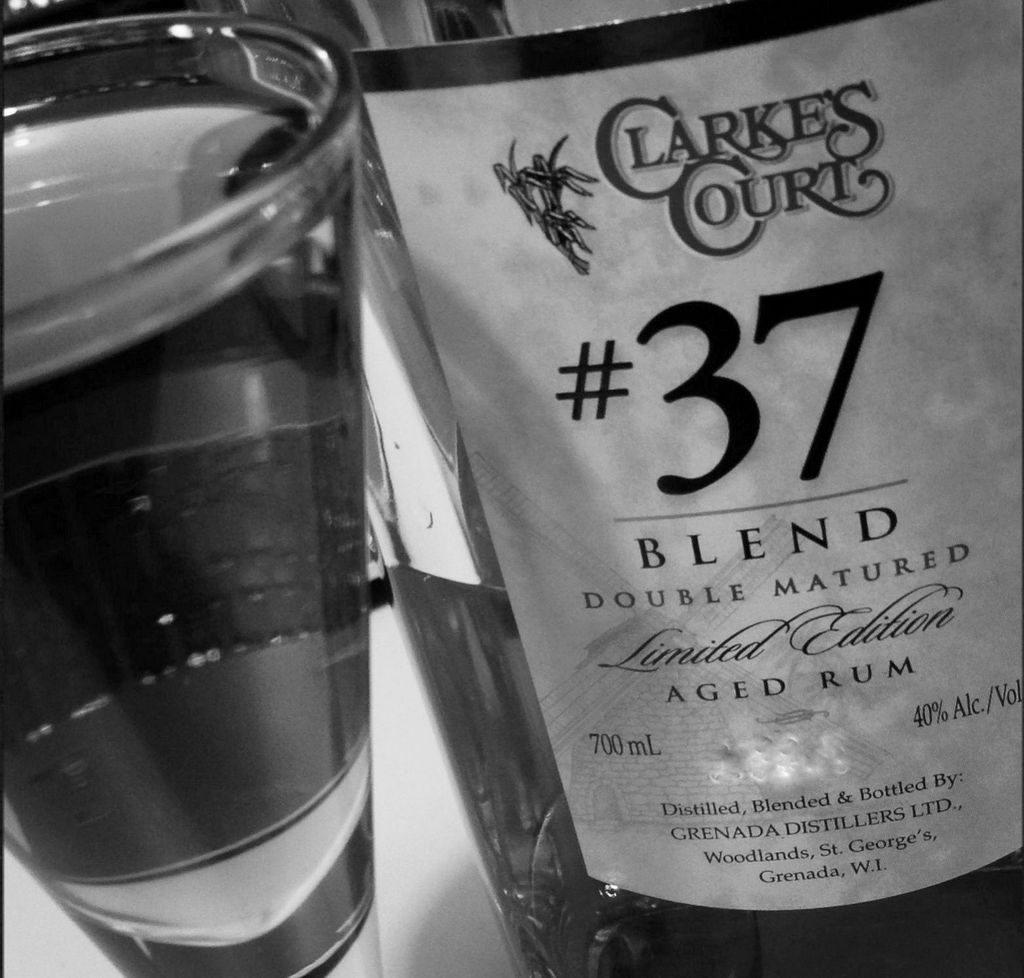

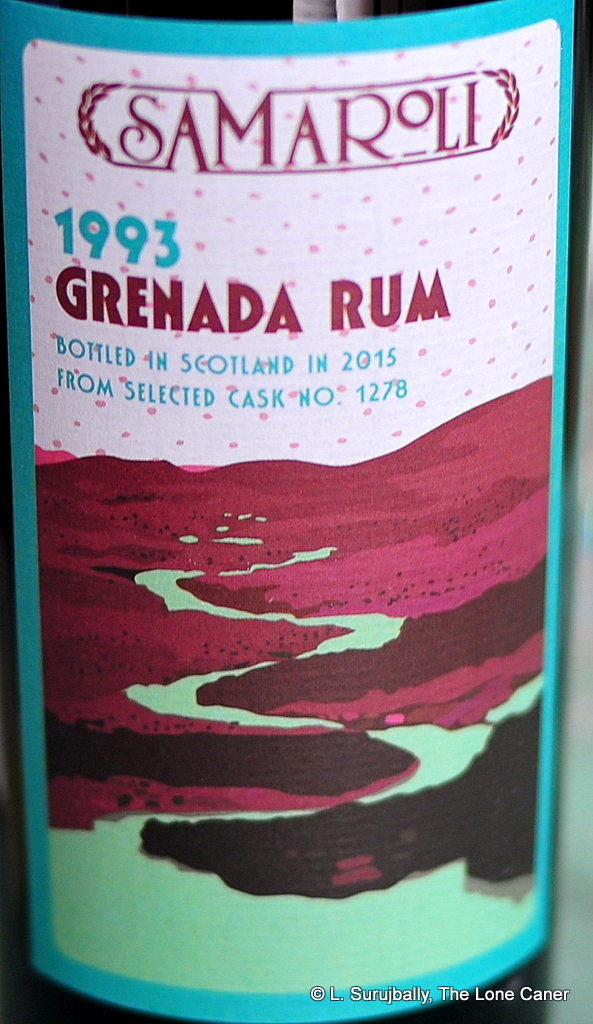

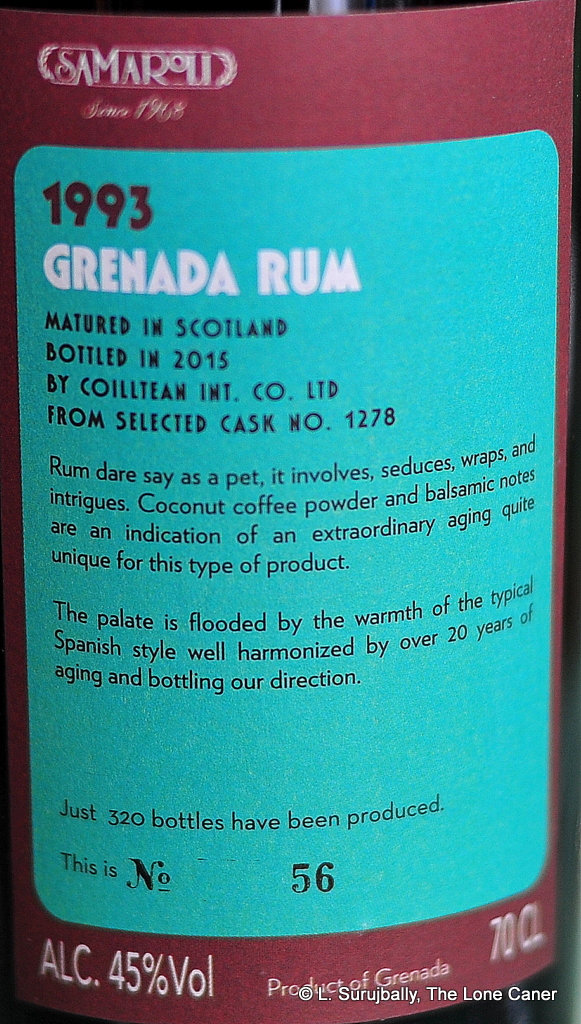

One such is this Samaroli rum sporting an impressive 22 years of continental ageing, hailing from Grenada – alas, not Rivers Antoine, but you can’t have everything (the rum very likely came from Westerhall – they ceased distilling in 1996 but were the only ones exporting bulk rum before that). You’ll look long and hard before you find any kind of write up about it, or anyone who owns it – not surprising when you consider the €340 price tag it fetches in stores and at auction. This is the second Grenada rum selected under the management of Antonio Bleve who took over operations at Samaroli in the mid 2000s and earned himself a similar reputation as Sylvio Samaroli (RIP), that of having the knack of picking right.

One such is this Samaroli rum sporting an impressive 22 years of continental ageing, hailing from Grenada – alas, not Rivers Antoine, but you can’t have everything (the rum very likely came from Westerhall – they ceased distilling in 1996 but were the only ones exporting bulk rum before that). You’ll look long and hard before you find any kind of write up about it, or anyone who owns it – not surprising when you consider the €340 price tag it fetches in stores and at auction. This is the second Grenada rum selected under the management of Antonio Bleve who took over operations at Samaroli in the mid 2000s and earned himself a similar reputation as Sylvio Samaroli (RIP), that of having the knack of picking right.  So what to make of this expensive two-decades-old Grenada rum released by an old and proud Italian house? Overall it’s really quite pleasant, avoids disaster and is tasty enough, just nothing special. I was expecting more. You’d be hard pressed to identify its provenance if tried blind. Like an SUV taking the highway, it stays firmly on the road without going anywhere rocky or offroad, perhaps fearing to nick the paint or muddy the tyres.

So what to make of this expensive two-decades-old Grenada rum released by an old and proud Italian house? Overall it’s really quite pleasant, avoids disaster and is tasty enough, just nothing special. I was expecting more. You’d be hard pressed to identify its provenance if tried blind. Like an SUV taking the highway, it stays firmly on the road without going anywhere rocky or offroad, perhaps fearing to nick the paint or muddy the tyres.