When we think of Haiti two names in rum immediately spring to mind: clairins and Barbancourt. This pair of diametrically opposite rum making styles dominate the conversation to such an extent that it is often overlooked that there are other distilleries on the island, like Barik / Moscoso, Agriterra / Himbert, Distillerie de la Rue (Nazon), Distillerie Lacrete, La Distillerie 1716, Beauvoir Leriche and Janel Mendard (among others). Granted most of these don’t do much branded work, stay within their regional market, or they sell bulk rum only (often clairins or their lookalikes that punch up lesser rums made by even cheaper brands), but they do exist and it’s a shame we don’t know more about them or their rums.

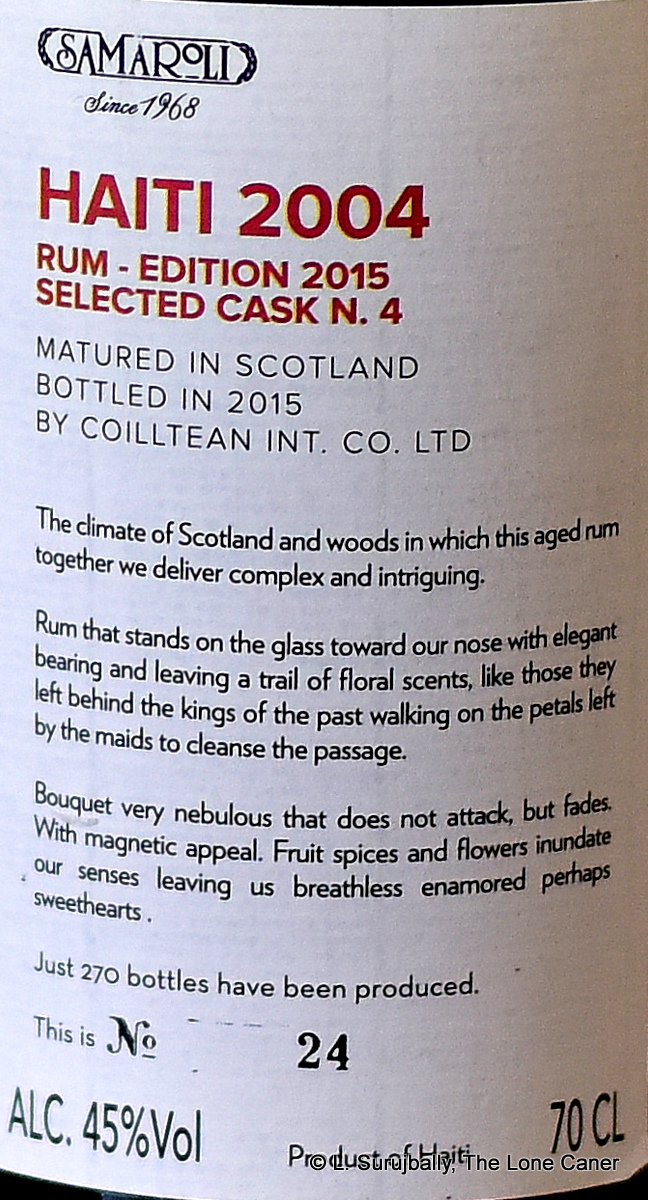

I make this point because the Samaroli 11 year old Haitian rum from 2004 which we are looking at today, doesn’t actually say which distillery in Haiti made it. Admittedly, this is a pedantic issue, since we can surmise with near-total assurance that it’s a Barbancourt distillate: they supply the majority of European brokers with bulk rum from Haiti while the others mentioned here tend to do local sales or over-the-border business in the Dominican Republic. But we don’t know for sure and all the ebay sites and auction listings for this rum and other Haitians that Samaroli bottled, do not disclose the source, so we’ll take it as an educated and probably correct guess for now.

I make this point because the Samaroli 11 year old Haitian rum from 2004 which we are looking at today, doesn’t actually say which distillery in Haiti made it. Admittedly, this is a pedantic issue, since we can surmise with near-total assurance that it’s a Barbancourt distillate: they supply the majority of European brokers with bulk rum from Haiti while the others mentioned here tend to do local sales or over-the-border business in the Dominican Republic. But we don’t know for sure and all the ebay sites and auction listings for this rum and other Haitians that Samaroli bottled, do not disclose the source, so we’ll take it as an educated and probably correct guess for now.

What else? Distilled in 2004 and released in 2015 at 45% ABV, the rum hews closely to the mantra Silvio Samaroli developed all those years ago, which said that at the intersection of medium age and medium strength is a nexus of the best of all possible aromas, textures and tastes, where neither the rawness of youth or the excessive oakiness of age can spoil the bottled distillate, and the price remains reasonable. Well, maybe, though what’s going on these days price-wise might give anyone pause to wonder whether that still holds true.

The rum does nose nicely, mind you: it starts off with a loud blurt of glue paint and nail polish, warm but not sharp and settles down into an almost elegant and very precise profile. Soft notes of sugar water, pear syrup, cherries, vanilla and coconut shavings cavort around the nose, offset by a delicate lining of citrus and florals and a subtle hint of deeper fruits, and herbs.

Overall the slightly briny palate is warm, but not obnoxious. Mostly, it’s relaxed and sweet, with pears, papayas, cucumbers plus maybe a single pimento for a sly kick at the back end. It’s not too complex – honestly, it’s actually rather shy, which may be another way of saying there’s not much going on here. But it still beats out a bunch of standard strength Spanish-heritage rons I had on the go that same day. What distinguishes the taste is its delicate mouthfeel, floral hints and the traces of citrus infused sugar cane sap, all quite nice. It’s all capped by a short and floral finish, delicate and spicy-sweet, which retains that slight brininess and darker fruits that are hinted at, without any effort to overwhelm.

Overall the slightly briny palate is warm, but not obnoxious. Mostly, it’s relaxed and sweet, with pears, papayas, cucumbers plus maybe a single pimento for a sly kick at the back end. It’s not too complex – honestly, it’s actually rather shy, which may be another way of saying there’s not much going on here. But it still beats out a bunch of standard strength Spanish-heritage rons I had on the go that same day. What distinguishes the taste is its delicate mouthfeel, floral hints and the traces of citrus infused sugar cane sap, all quite nice. It’s all capped by a short and floral finish, delicate and spicy-sweet, which retains that slight brininess and darker fruits that are hinted at, without any effort to overwhelm.

Formed in 1968 by the eponymous Italian gentleman, the firm made its bones in the 1970s in whiskies, branched into rums, and has a unicorn rum or two in its portfolio (like that near legendary 1948 blend); it is the distinguished inspiration for, and conceptual ancestor of, many Italian indies who came after…but by 2022 and even perhaps before that, Samaroli slipped in the younger generation’s estimation, lagging behind new and hungry independents like 1423, Rom Deluxe or Nobilis. These brash insurgents issued cask strength monsters crammed with 80+ points of proof that were aged to three decades, or boosted to unheard ester levels…and the more elegant, easier, civilized rums Samaroli was once known for, no longer command the same cachet.

Now, this quiet Haiti rum is not an undiscovered steal from yesteryear, or a small masterpiece of the indie bottler’s art – I’d be lying if I said that. It’s simply a nice little better-than-entry level sipper, quiet and relaxed and with just enough purring under the hood to not make it boring. But to me it also shows that Samaroli can continue to do their continental ageing thing and come out with something that — while not a brutal slug to the nuts like a clairin, or the sweet elegance of a well-aged Barbancourt or a crank-everything-up-to-”12” rum from an aggressive new indie — still manages to present decently and show off a profile that does the half-island no dishonour. In a time of ever larger bottle-stats (and attendant prices), too often done just for shock value and headlines, perhaps it is worth taking a look at a rum like this once in a while, if only to remind ourselves that there are always alternatives.

(#874)(82/100)

Other Notes

- It is assumed to be a column-still rhum; the source, whether molasses or sugar cane, is unstated and unknown.

- 270-bottle outturn

The nose doesn’t help narrow down the origin (though I have my suspicions), and the palate doesn’t either – but it

The nose doesn’t help narrow down the origin (though I have my suspicions), and the palate doesn’t either – but it

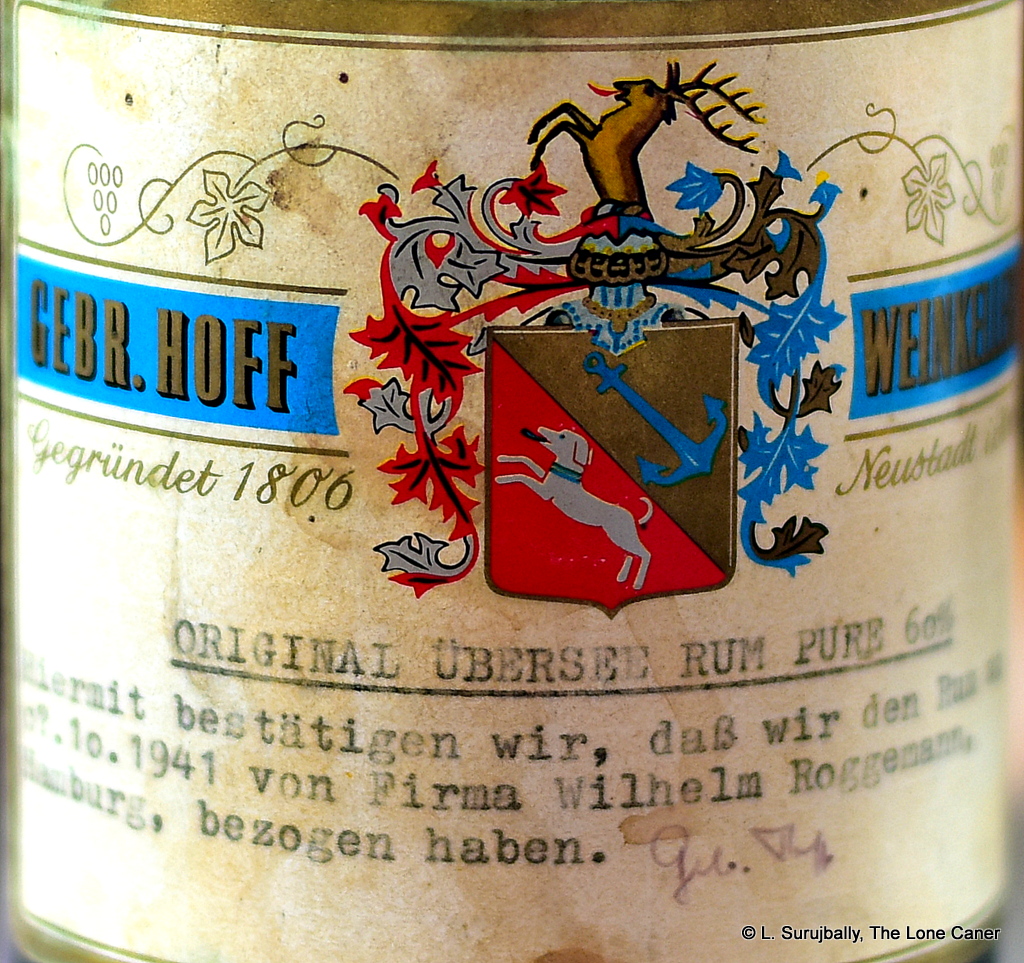

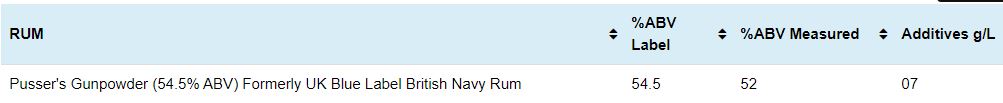

So let’s try it and see. Nose is, let me state right out, great. Sure, it’s rather rough and ready, spurring and booting around, but nicely rich and deep with initial aromas of butterscotch, caramel, brine, molasses. A nice dry and dusty old cardboard smell is exuded, and then a whiff of rotten fruits – and, as the Jamaicans have taught us, this is not necessarily a bad thing – to which is gradually added a fruity tinned cherry syrup, coconut shavings and vanilla. A few prunes and ripe peaches. Hints of glue, brine, humus and olive oil. It smells both musky and sweet, with anise popping in and out like a jack in the box. Glue, brine, humus and olive oil. So all in all, a lot going on in there, all nicely handled.

So let’s try it and see. Nose is, let me state right out, great. Sure, it’s rather rough and ready, spurring and booting around, but nicely rich and deep with initial aromas of butterscotch, caramel, brine, molasses. A nice dry and dusty old cardboard smell is exuded, and then a whiff of rotten fruits – and, as the Jamaicans have taught us, this is not necessarily a bad thing – to which is gradually added a fruity tinned cherry syrup, coconut shavings and vanilla. A few prunes and ripe peaches. Hints of glue, brine, humus and olive oil. It smells both musky and sweet, with anise popping in and out like a jack in the box. Glue, brine, humus and olive oil. So all in all, a lot going on in there, all nicely handled. Rumaniacs Review #123 | #800

Rumaniacs Review #123 | #800

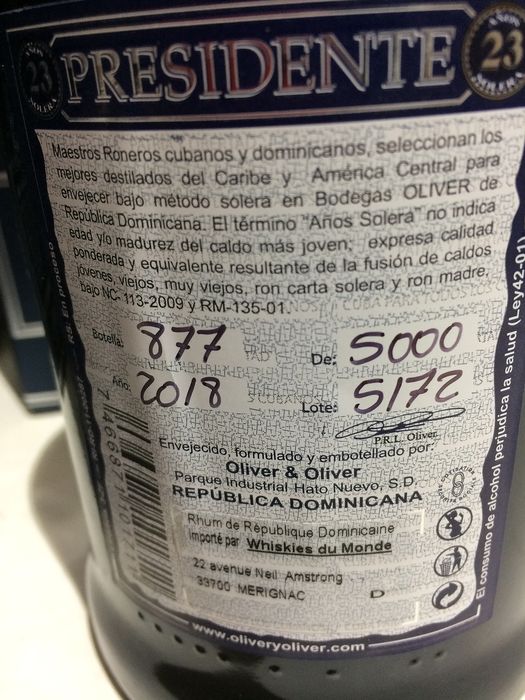

It gets no better when tasted. It’s very darkly sweet, liqueur-like, giving up flavours of prunes and stewed apples (again); dates; peaches in syrup, yes, more syrup, vanilla and a touch of cocoa. Honey, Cointreau, and both cloying and wispy at the same time, with a last gasp of caramel and toffee. The finish is thankfully short, sweet, thin, faint, nothing new except maybe some creme brulee. It’s a rum that, in spite of its big number and heroic Jose Marti visage screams neither quality or complexity. Mostly it yawns “boring!”

It gets no better when tasted. It’s very darkly sweet, liqueur-like, giving up flavours of prunes and stewed apples (again); dates; peaches in syrup, yes, more syrup, vanilla and a touch of cocoa. Honey, Cointreau, and both cloying and wispy at the same time, with a last gasp of caramel and toffee. The finish is thankfully short, sweet, thin, faint, nothing new except maybe some creme brulee. It’s a rum that, in spite of its big number and heroic Jose Marti visage screams neither quality or complexity. Mostly it yawns “boring!”

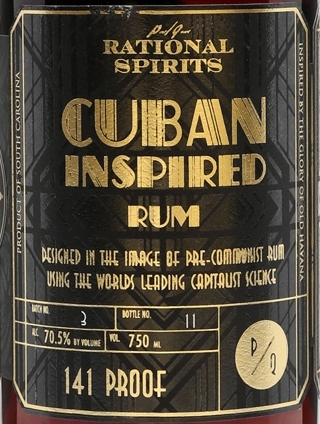

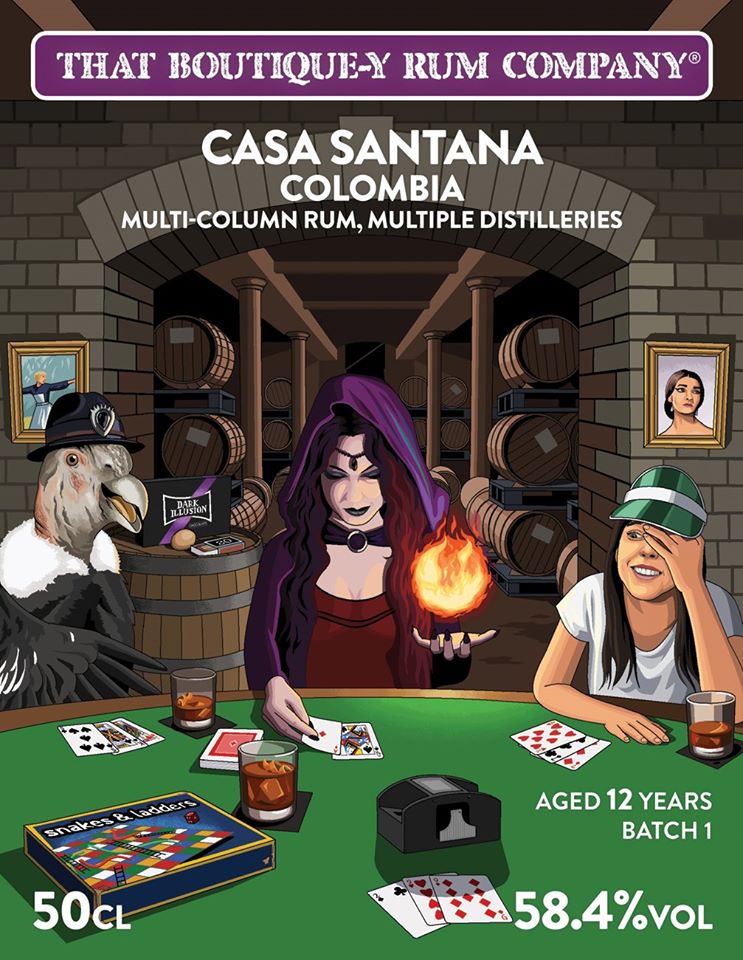

In spite of the high ABV, which lends a fair amount of initial sharpness and heat to the tongue until it burns away and settles down, it’s actually not that fierce. It becomes almost delicate, and there’s a nice vein of fruity sweetness running through, which enhances the flavours of apples, cider, green grapes, citrus, coconut, vanilla, and candied oranges. There’s also some of that polish and acetone remaining, neatly dampened by caramel and brown sugar, all balancing off well against each other. It retains that delicacy to the finish line and stays well behaved: a touch sweet throughout, with caramel (a bit much), vanilla, fruits, grapes, raisins, citrus, blancmange…not bad at all.

In spite of the high ABV, which lends a fair amount of initial sharpness and heat to the tongue until it burns away and settles down, it’s actually not that fierce. It becomes almost delicate, and there’s a nice vein of fruity sweetness running through, which enhances the flavours of apples, cider, green grapes, citrus, coconut, vanilla, and candied oranges. There’s also some of that polish and acetone remaining, neatly dampened by caramel and brown sugar, all balancing off well against each other. It retains that delicacy to the finish line and stays well behaved: a touch sweet throughout, with caramel (a bit much), vanilla, fruits, grapes, raisins, citrus, blancmange…not bad at all.

This process provides a tasting profile that reminds me of nothing so much than a slightly addled wooden still-rum from El Dorado: it’s sweet, feels the slightest bit sticky, and has strong notes of dark fruits, red licorice, plums, raisins and an almond chocolate bar gone soft in the heat. There’s other stuff in there as well – some caramel, vanilla, pepper again, light orange peel, but overall the whole thing is not particularly complex, and it ambles easily towards a short and gentle finish of no particular distinction that pretty much displays some dark fruit, caramel, anise and molasses, and that’s about it.

This process provides a tasting profile that reminds me of nothing so much than a slightly addled wooden still-rum from El Dorado: it’s sweet, feels the slightest bit sticky, and has strong notes of dark fruits, red licorice, plums, raisins and an almond chocolate bar gone soft in the heat. There’s other stuff in there as well – some caramel, vanilla, pepper again, light orange peel, but overall the whole thing is not particularly complex, and it ambles easily towards a short and gentle finish of no particular distinction that pretty much displays some dark fruit, caramel, anise and molasses, and that’s about it. So, until we know more, focus on the rum itself. It’s quiet and gentle and some cask strength lovers might say – not without justification – that it’s insipid. It has some good tastes, simple but okay, and hews to a profile with which we’re not entirely unfamiliar. It has a few off notes and a peculiar substrate of something different, which is a good thing. So in the end,

So, until we know more, focus on the rum itself. It’s quiet and gentle and some cask strength lovers might say – not without justification – that it’s insipid. It has some good tastes, simple but okay, and hews to a profile with which we’re not entirely unfamiliar. It has a few off notes and a peculiar substrate of something different, which is a good thing. So in the end,

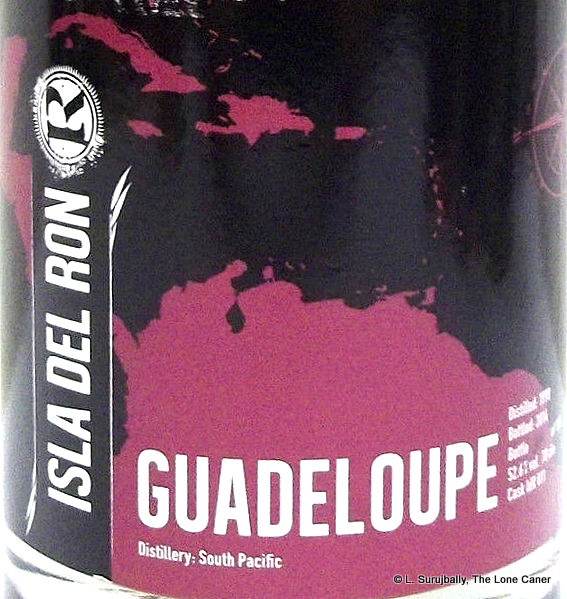

All that comes together in a rhum of uncommonly original aroma and taste. It opens with smells that confirm its provenance as an agricole, and it displays most of the hallmarks of a rhum from the blanc side (herbs, grassiness, crisp citrus and tart fruits)…but that out of the way, evidently feels it is perfectly within its rights to take a screeching ninety degree left turn into the woods. Woody and even meaty notes creep out, which seem completely out of place, yet somehow work. This all combines with salt, rancio, brine, and olives to mix it up some more, but the overall effect is not unpleasant – rather it provides a symphony of undulating aromas that move in and out, no single one ever dominating for long before being elbowed out of the way by another.

All that comes together in a rhum of uncommonly original aroma and taste. It opens with smells that confirm its provenance as an agricole, and it displays most of the hallmarks of a rhum from the blanc side (herbs, grassiness, crisp citrus and tart fruits)…but that out of the way, evidently feels it is perfectly within its rights to take a screeching ninety degree left turn into the woods. Woody and even meaty notes creep out, which seem completely out of place, yet somehow work. This all combines with salt, rancio, brine, and olives to mix it up some more, but the overall effect is not unpleasant – rather it provides a symphony of undulating aromas that move in and out, no single one ever dominating for long before being elbowed out of the way by another.

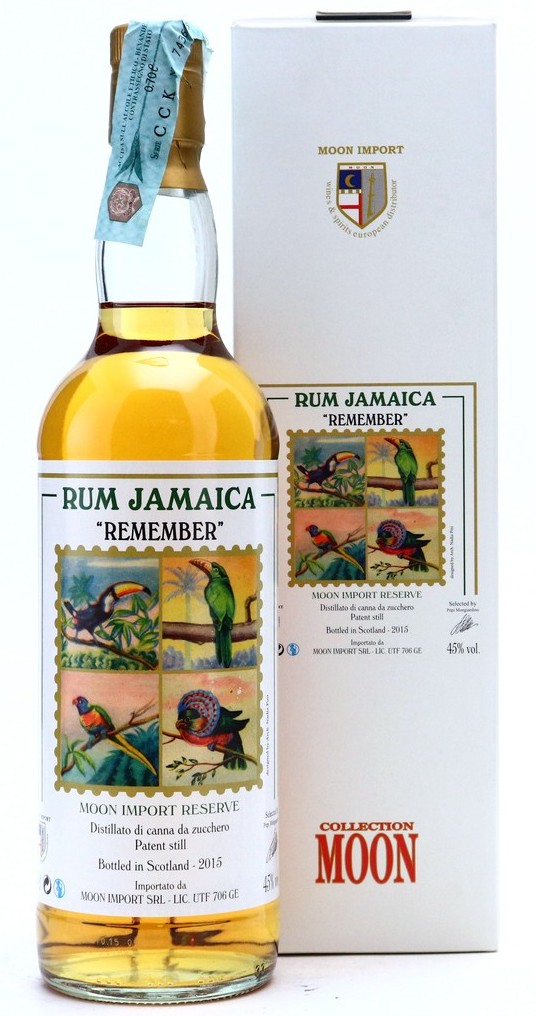

Normally, such a rum wouldn’t interest me much, but with the massive reputations the New Jamaicans have been building for themselves, it made me curious so I grudgingly parted with some coin to get a sample. That was the right decision, because this thing turned out to be less an undiscovered steal than a low-rent Jamaican wannabe for those who don’t care about and can’t tell one Jamaican rum from another, know Appleton and stop there. The rum takes great care not to go beyond such vanilla illusions, since originality is not its forte and it takes inoffensive pleasing-the-sipper as its highest goal.

Normally, such a rum wouldn’t interest me much, but with the massive reputations the New Jamaicans have been building for themselves, it made me curious so I grudgingly parted with some coin to get a sample. That was the right decision, because this thing turned out to be less an undiscovered steal than a low-rent Jamaican wannabe for those who don’t care about and can’t tell one Jamaican rum from another, know Appleton and stop there. The rum takes great care not to go beyond such vanilla illusions, since originality is not its forte and it takes inoffensive pleasing-the-sipper as its highest goal.

That provided, let’s get right into it then, nose forward. It’s warm but indistinct, which is to say, it’s a blended melange of several things — molasses, coffee (like

That provided, let’s get right into it then, nose forward. It’s warm but indistinct, which is to say, it’s a blended melange of several things — molasses, coffee (like

Opinion / Company background

Opinion / Company background

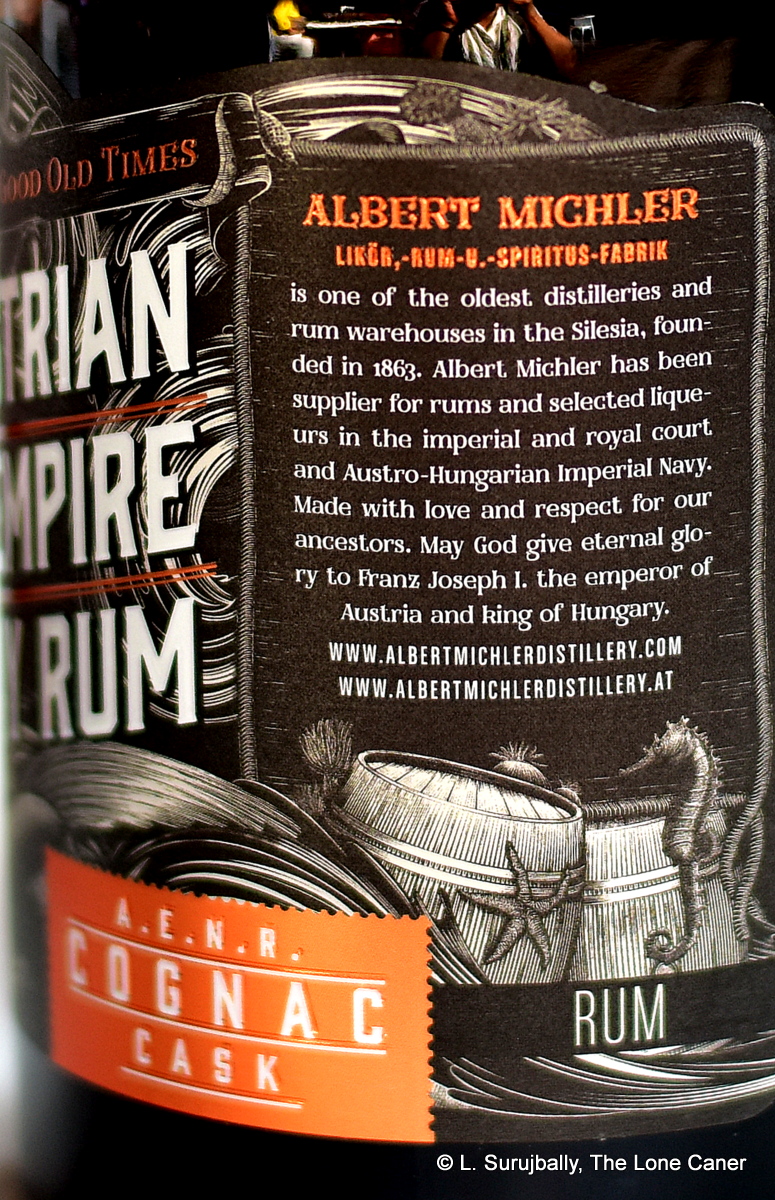

There are no records on whether the Austrian or Austro-Hungarian Navy ever used it or was supplied by the Michler distillery. Somehow I doubt it – it was far more likely it followed in the tradition of rum

There are no records on whether the Austrian or Austro-Hungarian Navy ever used it or was supplied by the Michler distillery. Somehow I doubt it – it was far more likely it followed in the tradition of rum

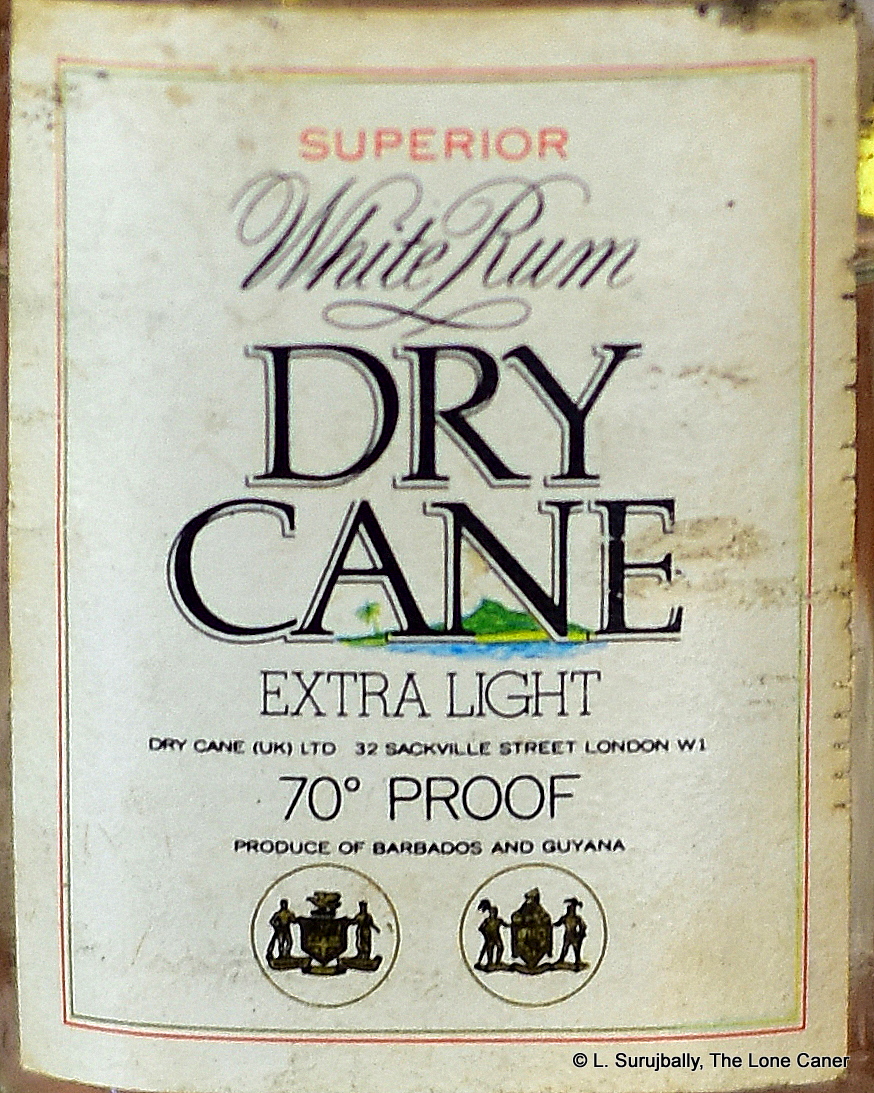

My inference is therefore that Dry Cane was a financing vehicle or shell company or wholly owned subsidiary set up for a short time to limit the exposure of the parent company (or Kinloch), as it dabbled in being an independent bottler — and just as quickly retreated, for no further products were ever made so far as I can tell. But since S&S also acquired a Gibraltar drinks franchise in 1968 and gained the concession to operate a duty free shop at Gibraltar airport in 1973, I suspect this was the rationale behind creating the rums in the first place, through the reason for its cessation is unknown. Certainly by the time S&S moved out of Sackville Street in the 1980s and to Gibraltar (where they remain to this day as part of a large conglomerate), the rum was no longer on sale.

My inference is therefore that Dry Cane was a financing vehicle or shell company or wholly owned subsidiary set up for a short time to limit the exposure of the parent company (or Kinloch), as it dabbled in being an independent bottler — and just as quickly retreated, for no further products were ever made so far as I can tell. But since S&S also acquired a Gibraltar drinks franchise in 1968 and gained the concession to operate a duty free shop at Gibraltar airport in 1973, I suspect this was the rationale behind creating the rums in the first place, through the reason for its cessation is unknown. Certainly by the time S&S moved out of Sackville Street in the 1980s and to Gibraltar (where they remain to this day as part of a large conglomerate), the rum was no longer on sale. Palate – Light and inoffensive, completely bland. Pears, sugar water, some mint. You can taste a smidgen of alcohol behind all that, it’s just that there’s nothing really serious backing it up or going on.

Palate – Light and inoffensive, completely bland. Pears, sugar water, some mint. You can taste a smidgen of alcohol behind all that, it’s just that there’s nothing really serious backing it up or going on.

Colour – Very dark brown

Colour – Very dark brown