Rumaniacs Review R-113 | 0717

My apologies to anyone who has bought and enjoyed the Superb Tortuga Light Rum on some Caribbean cruise that docked in the Cayman Islands for the last three decades or more….but it really isn’t much of anything. It continues to sell though, even if nowadays its star has long faded and you’d be hard pressed to find anyone of the current crop of writers or commentators who has ever tried it.

The white rum, a blend of unidentified, unspecified Jamaican and Barbadian distillates bottled at 40%, is not really superb and not from the island of Tortuga north of Haiti (but from the Cayman Islands 500 miles to the west of there); it’s filtered and bleached to within an inch of its life, is colourless, lifeless and near out tasteless. It incites not gasps of envy and jealous looks, but headshakes and groans of despair at yet another downmarket rum marketed with ruthless efficiency to the holiday crowd, and which for some reason, manages to score an unbelievable “Best Buy” rating of 85-89 points from someone at Wine Enthusiast who should definitely never be given a white Habitation Velier to try lest it diminish our personal stocks of rums that really are superb.

Think I’m harsh? Perchance I suffer from enforced isolation and cabin fever? Bad hair day? Feel free to contradict what I’m smelling: a light, sharp, acetone-like nose that at best provides a note of cucumbers, sugar water and sweet cane sap with perhaps a pear or two thrown in. If you strain, real hard, you might detect an overripe pineapple, a squirt of lemon rind and a banana just beginning to go. Observe the use of the singular here.

Still not convinced? Please taste. No, rather, please swill, gulp and gargle. Won’t make a difference. There’s so little here to work with, and what’s frustrating about it, is that had it been a little less filtered, a little less wussied-down, then those flavours that could – barely – be discerned, might have shone instead of feeling dull and anaemic. I thought I noted something sweet and watery, a little pineapple juice, that pear again, a smidgen of vanilla, maybe a pinch of salt and that, friends and neighbors is me reaching and straining (and if the image you have is of me on the ivory throne trying to pass a gallstone, well…). Finish is short and unexceptional: some vanilla, some sugar water and a last gasp of cloves and white fruits, then it all hisses away like steam, poof.

At end, what we’re underwhelmed with is a sort of boring, insistent mediocrity. Its core constituents are themselves made well enough that even with all the dilution and filtration the rum doesn’t fall flat on its face, just produced too indifferently to elicit anything but apathy, and maybe a motion to the waiter to freshen the rum punch. And so while it’s certainly a rum of its own time, the 1980s, it’s surely – and thankfully – not one for these.

(72/100)

Other notes

- The Tortuga rum is not named after the island, but to commemorate the original name of the Cayman Islands, “Las Tortugas,” meaning “The Turtles.”

- The “Light” described here is supposedly a blend of rums aged 1-3 years.

- The company was established in 1984 by two Cayman Airways employees, Robert and Carlene Hamaty, and their first products were two blended rums, Gold and Light. Blending and bottling took place in Barbados according to the label, but this information may be dated as my sample came from a late-1980s bottle. Since its founding, the company has expanded both via massive sales of duty free rums to visitors coming in via both air and sea. The range is now expanded beyond the two original rum types to flavoured and spiced rums, and even some aged ones, which I have never seen for sale. Maybe one has to go there to get one. In 2011 the Jamaican conglomerate JP Group acquired a majority stake in Tortuga’s parent company, which, aside from making rums, had by this time also created a thriving business in rum cakes and flavoured specialty foods.

I should begin by warning you that this rum is sold on a very limited basis, pretty much always to favoured bars in the Philippines, and then not even by the barrel, but by the bottle from that barrel – sort of a way to say “Hey look, we can make some cool sh*t too! Wanna buy some of the other stuff we make?”. Export is clearly not on the cards…at least, not yet.

I should begin by warning you that this rum is sold on a very limited basis, pretty much always to favoured bars in the Philippines, and then not even by the barrel, but by the bottle from that barrel – sort of a way to say “Hey look, we can make some cool sh*t too! Wanna buy some of the other stuff we make?”. Export is clearly not on the cards…at least, not yet.

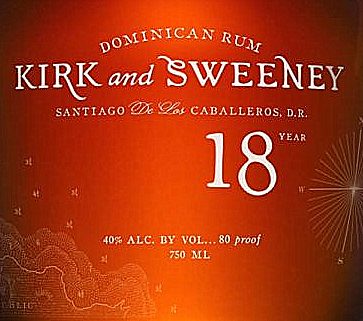

This is not to say that there isn’t some interesting stuff to be found. Take the nose, for example. It smells of salted caramel, vanilla ice cream, brown sugar, a bit of molasses, and is warm, quite light, with maybe a dash of mint and basil thrown in. But taken together, what it has is the smell of a milk shake, and there doesn’t seem to be much in the way of startling originality – not exactly what 18 years of ageing would give you, pleasant as it is. It’s soft and easy, that’s all. No thinking required.

This is not to say that there isn’t some interesting stuff to be found. Take the nose, for example. It smells of salted caramel, vanilla ice cream, brown sugar, a bit of molasses, and is warm, quite light, with maybe a dash of mint and basil thrown in. But taken together, what it has is the smell of a milk shake, and there doesn’t seem to be much in the way of startling originality – not exactly what 18 years of ageing would give you, pleasant as it is. It’s soft and easy, that’s all. No thinking required.

Colour – Amber

Colour – Amber

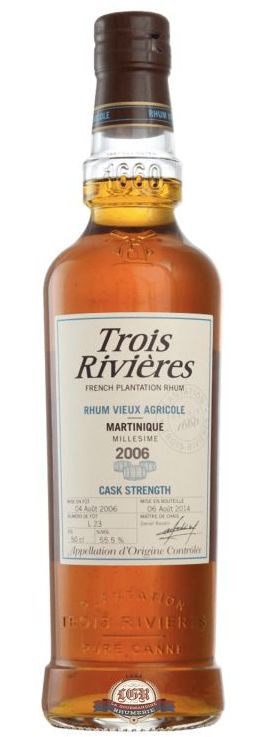

The Trois Rivières Brut de fût Millésime 2006 (which is its official name) is relatively unusual: it’s aged in new American oak barrels, not Limousin, and bottled at cask strength, not the more common 43-48%. And that gives it a solidity that elevates it somewhat over the standards we’ve become used to. Let’s start, as always, with the nose — it just becomes more assertive, and more clearly defined…although it seems somehow gentler (which is quite a neat trick when you think about it). It is redolent of caramel and vanilla first off, and then adds green apples, tart yoghurt, pears, white guavas, watermelon and papaya, and behind all that is a delectable series of herbs – rosemary, dill, even a hint of basil and aromatic pipe tobacco.

The Trois Rivières Brut de fût Millésime 2006 (which is its official name) is relatively unusual: it’s aged in new American oak barrels, not Limousin, and bottled at cask strength, not the more common 43-48%. And that gives it a solidity that elevates it somewhat over the standards we’ve become used to. Let’s start, as always, with the nose — it just becomes more assertive, and more clearly defined…although it seems somehow gentler (which is quite a neat trick when you think about it). It is redolent of caramel and vanilla first off, and then adds green apples, tart yoghurt, pears, white guavas, watermelon and papaya, and behind all that is a delectable series of herbs – rosemary, dill, even a hint of basil and aromatic pipe tobacco.

Okay so, on to palate. Straw yellow in the glass, it was softer and less intense, which, for a forty percenter, was both good and bad. Here the grassy and herbal notes took on more prominence, as did citrus, some tart unsweetened yoghurt, honey and cane juice. The youth was evident in the slight sharpness and lack of real roundness – the two years of ageing had

Okay so, on to palate. Straw yellow in the glass, it was softer and less intense, which, for a forty percenter, was both good and bad. Here the grassy and herbal notes took on more prominence, as did citrus, some tart unsweetened yoghurt, honey and cane juice. The youth was evident in the slight sharpness and lack of real roundness – the two years of ageing had  In 1923 La Mauny was sold to Théodore and Georges Bellonnie who enlarged and brought in new facilities such as a distillation column, new grinding mills and a steam engine. The distillery expanded hugely thanks to increased output and good marketing strategies and La Mauny rhums began to be exported around 1950. In 1970, after the Bellonnie brothers had both passed away, the Bordeaux traders and old-Martinique family of Bourdillon teamed up with Théodore Bellonnie’s widow and created the BBS Group. The company grew strongly, launching on the French market in 1977. Jean Pierre Bourdillon, who ran the new group, undertook to modernize La Mauny. He began by reorganizing the fields in order to make them accessible to mechanical harvesting and built a new distillery in 1984 (with a fourth mill, a three column still and a new boiler) a few hundred meters from the old one, increasing the cane crushing capacity and buying the equipment of the Saint James distillery in Acaiou, unused since 1958.

In 1923 La Mauny was sold to Théodore and Georges Bellonnie who enlarged and brought in new facilities such as a distillation column, new grinding mills and a steam engine. The distillery expanded hugely thanks to increased output and good marketing strategies and La Mauny rhums began to be exported around 1950. In 1970, after the Bellonnie brothers had both passed away, the Bordeaux traders and old-Martinique family of Bourdillon teamed up with Théodore Bellonnie’s widow and created the BBS Group. The company grew strongly, launching on the French market in 1977. Jean Pierre Bourdillon, who ran the new group, undertook to modernize La Mauny. He began by reorganizing the fields in order to make them accessible to mechanical harvesting and built a new distillery in 1984 (with a fourth mill, a three column still and a new boiler) a few hundred meters from the old one, increasing the cane crushing capacity and buying the equipment of the Saint James distillery in Acaiou, unused since 1958.

The Cor Cor “Green”, cousin to the

The Cor Cor “Green”, cousin to the

The full and rather unwieldy title of the rum today is the Chantal Comte Rhum Agricole 1975 Extra Vieux de la Plantation de la Montagne Pelée, but let that not dissuade you. Consider it a column-still, cane-juice rhum aged around eight years, sourced from Depaz when it was still André Depaz’s property and the man was – astoundingly enough in today’s market – having real difficulty selling his aged stock. Ms. Comte, who was born in Morocco but had strong Martinique familial connections, had interned in the wine world, and was also mentored by Depaz and Paul Hayot (of Clement) in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when Martinique was suffering from overstock and poor sales.. And having access at low cost to such ignored and unknown stocks allowed her to really pick some amazing rums, of this is one.

The full and rather unwieldy title of the rum today is the Chantal Comte Rhum Agricole 1975 Extra Vieux de la Plantation de la Montagne Pelée, but let that not dissuade you. Consider it a column-still, cane-juice rhum aged around eight years, sourced from Depaz when it was still André Depaz’s property and the man was – astoundingly enough in today’s market – having real difficulty selling his aged stock. Ms. Comte, who was born in Morocco but had strong Martinique familial connections, had interned in the wine world, and was also mentored by Depaz and Paul Hayot (of Clement) in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when Martinique was suffering from overstock and poor sales.. And having access at low cost to such ignored and unknown stocks allowed her to really pick some amazing rums, of this is one. Given Japan has several rums which have made these pages (

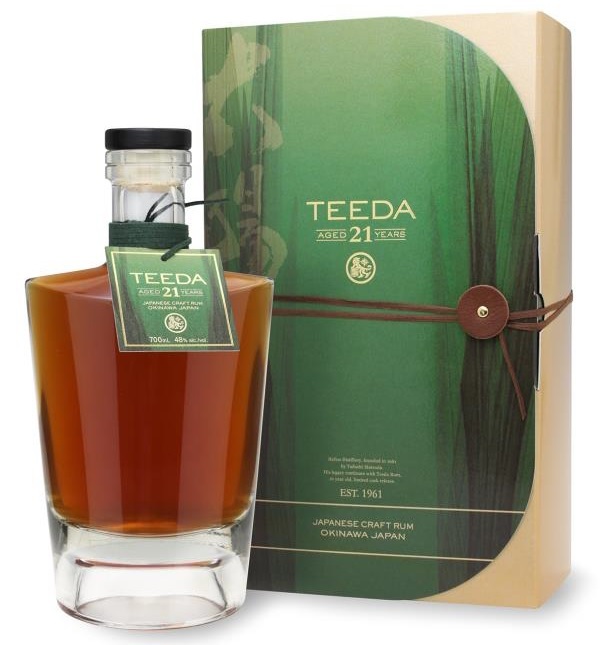

Given Japan has several rums which have made these pages ( The Cor Cor Red was more generous on the palate than the nose, and as with many Japanese rums I’ve tried, it’s quite distinctive. The tastes were somewhat offbase when smelled, yet came together nicely when tasted. Most of what we might deem “traditional notes” — like nougat, or toffee, caramel, molasses, wine, dark fruits, that kind of thing — were absent; and while their (now closed) website rather honestly remarked back in 2017 that it was not for everyone, I would merely suggest that this real enjoyment is probably more for someone (a) interested in Asian rums (b) looking for something new and (c) who is cognizant of local cuisine and spirits profiles, which infuse the makers’ designs here. One of the reasons the rum tastes as it does, is because the master blender used to work for one of the awamori makers on Okinawa (it is a spirit akin to Shochu), and wanted to apply the methods of make to rum as well. No doubt some of the taste profile he preferred bled over into the final product as well.

The Cor Cor Red was more generous on the palate than the nose, and as with many Japanese rums I’ve tried, it’s quite distinctive. The tastes were somewhat offbase when smelled, yet came together nicely when tasted. Most of what we might deem “traditional notes” — like nougat, or toffee, caramel, molasses, wine, dark fruits, that kind of thing — were absent; and while their (now closed) website rather honestly remarked back in 2017 that it was not for everyone, I would merely suggest that this real enjoyment is probably more for someone (a) interested in Asian rums (b) looking for something new and (c) who is cognizant of local cuisine and spirits profiles, which infuse the makers’ designs here. One of the reasons the rum tastes as it does, is because the master blender used to work for one of the awamori makers on Okinawa (it is a spirit akin to Shochu), and wanted to apply the methods of make to rum as well. No doubt some of the taste profile he preferred bled over into the final product as well.

Colour – Light Gold

Colour – Light Gold

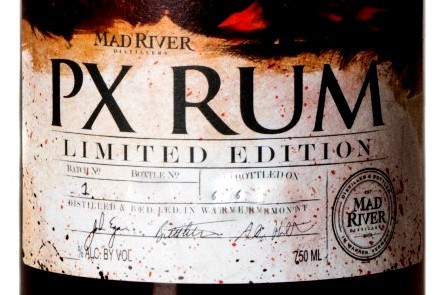

Here’s what we know – made from rendered sugar cane juice (“honey”), fermented for 72 hours using wild yeast, column distilled, then aged in all kinds of barrels – American oak (ex-bourbon), cognac, Pedro Ximenez and also Marcuya “fruit of passion” wood from Paraguay. Once that’s done, the resultant rons are blended to form the final product. The age is currently unknown — I’ll update this paragraph if I get feedback from their marketing folks — but I’ll hazard a guess it’s medium…about 3-6 years. Little of this, by the way, is noted on the label, which only says it is a Paraguayan rum, commemorates the 1869 battle, is aged in oak vats and 40%. Wonderful. Clearly the word “disclosure” gets more lip service than real purchase over there.

Here’s what we know – made from rendered sugar cane juice (“honey”), fermented for 72 hours using wild yeast, column distilled, then aged in all kinds of barrels – American oak (ex-bourbon), cognac, Pedro Ximenez and also Marcuya “fruit of passion” wood from Paraguay. Once that’s done, the resultant rons are blended to form the final product. The age is currently unknown — I’ll update this paragraph if I get feedback from their marketing folks — but I’ll hazard a guess it’s medium…about 3-6 years. Little of this, by the way, is noted on the label, which only says it is a Paraguayan rum, commemorates the 1869 battle, is aged in oak vats and 40%. Wonderful. Clearly the word “disclosure” gets more lip service than real purchase over there.

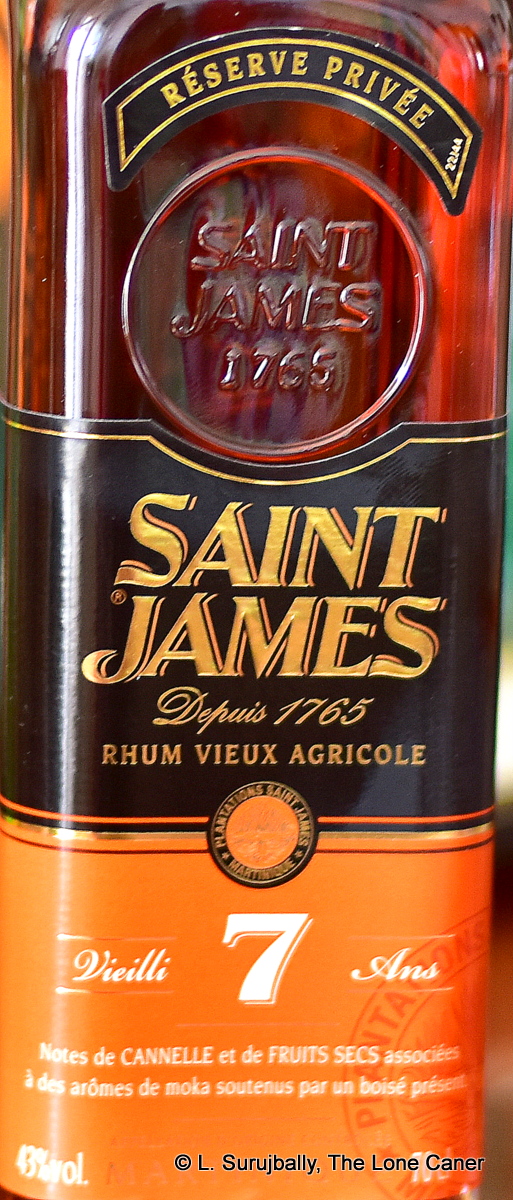

Ah but when sipped, all that changes, and the clodhoppers go away and it dons a pair of ballet slippers. It’s stunningly fragrant, not quite delicate – that ballerina does have an extra pound or two – very firm and robust in flavour profile. Just on the first sip you can taste flowers, pears, papaya, honey, vanilla, raisins, grapes, all pulled together with a delectable light and salty note. There are nice citrus hints, a tease from the oak, ginger and cinnamon, and overall, it sips as nicely as it mixes. The finish is well handled, though content to play it safe – things are beginning to quieten down here, and it fades quietly without stomping on you – and certainly nothing new or original comes into being; the rhum is content to follow where the nose and palate led – fruits, pineapple, spices, ginger, vanilla – without breaking any new ground.

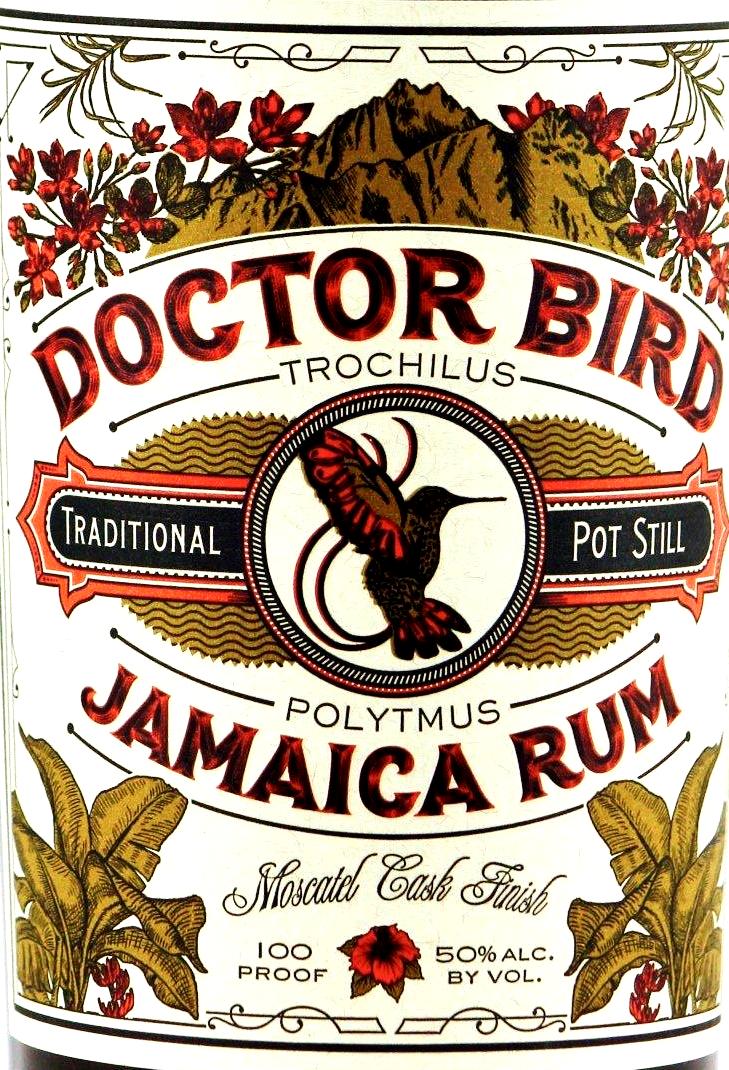

Ah but when sipped, all that changes, and the clodhoppers go away and it dons a pair of ballet slippers. It’s stunningly fragrant, not quite delicate – that ballerina does have an extra pound or two – very firm and robust in flavour profile. Just on the first sip you can taste flowers, pears, papaya, honey, vanilla, raisins, grapes, all pulled together with a delectable light and salty note. There are nice citrus hints, a tease from the oak, ginger and cinnamon, and overall, it sips as nicely as it mixes. The finish is well handled, though content to play it safe – things are beginning to quieten down here, and it fades quietly without stomping on you – and certainly nothing new or original comes into being; the rhum is content to follow where the nose and palate led – fruits, pineapple, spices, ginger, vanilla – without breaking any new ground. The strangely named Doctor Bird rum is another company’s response to

The strangely named Doctor Bird rum is another company’s response to

Anyway, this was a 12 year old, continentally-aged Guyanese rum (no still is mentioned, alas), of unknown outturn, aged 12 years in Laphroaig whisky casks and released at the 46% strength that was once a near standard for rums brought out by

Anyway, this was a 12 year old, continentally-aged Guyanese rum (no still is mentioned, alas), of unknown outturn, aged 12 years in Laphroaig whisky casks and released at the 46% strength that was once a near standard for rums brought out by

Palate – Even if they didn’t say so on the label, I’d say this is almost completely Guyanese just because of the way all the standard wooden-still tastes are so forcefully put on show – if there

Palate – Even if they didn’t say so on the label, I’d say this is almost completely Guyanese just because of the way all the standard wooden-still tastes are so forcefully put on show – if there