Just as we don’t see Americans making too many full proof rums, it’s also hard to see them making true agricoles, especially since the term is so tightly bound up with the spirits of the French islands.

Just as we don’t see Americans making too many full proof rums, it’s also hard to see them making true agricoles, especially since the term is so tightly bound up with the spirits of the French islands.

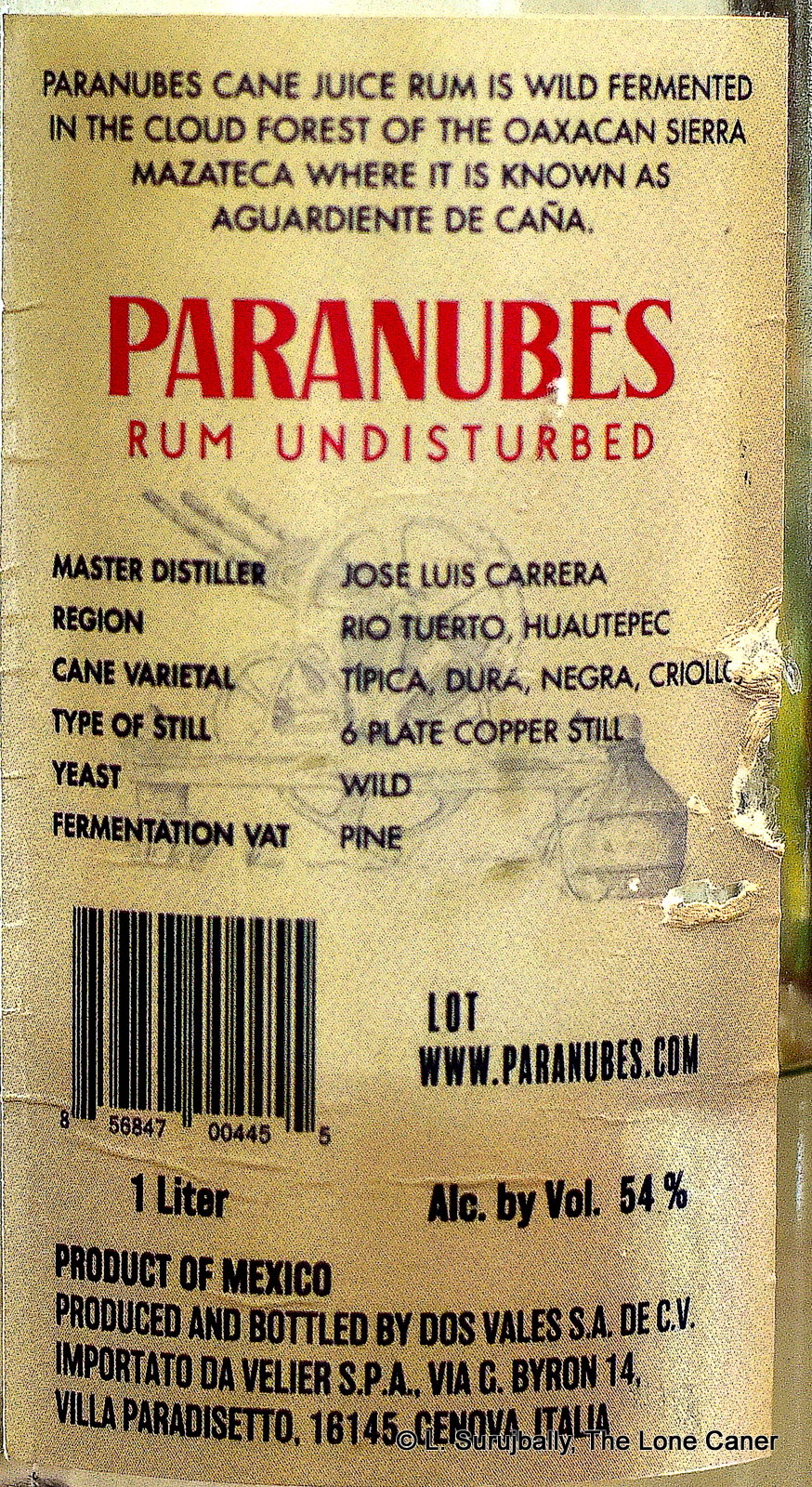

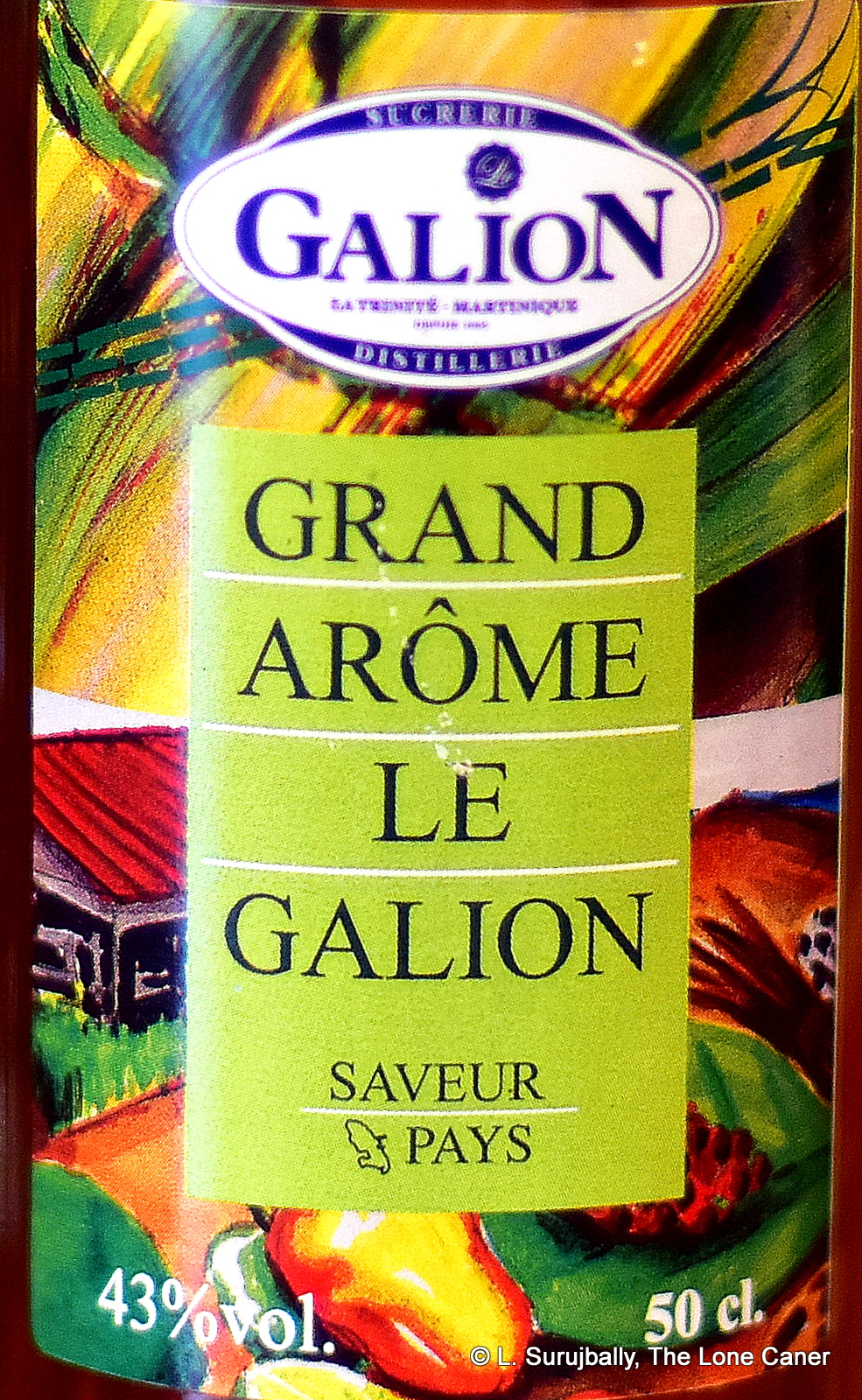

Agricole, let it be remembered, is the French term for agricultural rums made from pure sugar cane juice, and called such to distinguish them (not without a little Gallic disdain, to be sure) from traditionnels, or traditional rums, which are made from molasses, a by product of the sugar making process. For the most part, having much to do with the finances, molasses rums are much preferred by producers, because the issues of storage and spoilage which afflicts cane juice (it can go bad in just a few days) – that’s one reason why agricoles are closely associated with actual sugar estates with a distillery nearby – not always easy in a country the size of the USA where there is much greater separation between the two. (Note also: by EU law (but not that of the US) the term “agricole” can only be used by French Overseas Departments (Martinique, Guadeloupe, Reunion and French Guiana) and Madeira…nobody else. A lot of distilleries the world over ignore this in practice, until time comes to sell their product in the EU)

St. George’s, a 1982-established California distillery much better known for its gins, absinthes, vodkas and whiskies, get their fresh cut cane from Imperial Valley just to the east of San Diego along the Mexican border, and when a load comes in, they crush it immediately, add the yeast and ferment (duration unknown) before running it through a pot still (Josh Miller spoke of a hybrid pot/column still when he visited them in 2013 but St. George’s wrote to me and said “pot” for sure). The resultant spirit is rested for a short while in stainless steel tanks, with some being drawn off to age for a few years in oak, the rest being bottled at 43%. My version was based on the 2014 harvest according to the sample info, and was therefore issued in that year.

On the nose…oy! What was this? Vegetable soup, or (take your pick) meatballs, dumplings, dim sum or spring rolls…that kind of thing. Also vinegar, soy, pickles and fish sauce, a pot of brine and what felt like three bags of olives. Behind all that is a sharp edge, like a red wine gone off somehow, and whatever fruits there were took a reluctant step back – so much so that the first thoughts that ran through my mind as I smelled the rum was it was a low rent clairin that tried for the brass ring but ran out of steam. Still – nice. Adventurous. Different. I like that in a white rum.

Alas, the palate, after that jarringly original overture that so piqued my interest, seemed to go to sleep, a function of the 43% ABV maybe, and a reminder that pungent rums like unaged whites don’t always succeed when dialled down to a somnolent standard strength. Still, it did wake up after I ignored it for a bit, and gave a twitch of sugar water and watermelons, fresh-cut pears, vanilla and citrus, very light and very pleasant. Yes there was a sort of creaminess and black bread, behind which lurked the brine and olives (lots of both), but the rum seemed to have problems deciding whether it wanted to be a crowd pleaser or something truly original such as the nose had promised, and the finish – long, dry, salty, lightly fruity, sweetly watery – just followed the palate into a docile conclusion.

Truth is, the whole experience was schizophrenic – it started off with fire and smoke and major f**ken attitude, then just lost its mojo and sagged against the wall. For all the unbalanced helping of crazy with which it opened, I liked that off-kilter nose a lot better than everything that followed because it showed all the potential that failed to be realized later on. An unaged pot-still white should be a little off-base – anything else and you have a mere cocktail ingredient and there are already enough of those around.

That said, it’s not that I actively disliked the rum…just that I felt there was nothing serious here: nothing badass that dared to offend…or inspire (say what you will about the TECC and TECA rums from NRJ and their barking-mad taste profiles, they had real balles). So, at end, it’s a light alcohol with great promise (how it smelled) and too little follow-through (palate and finish). Cyril of DuRhum reviewed this same edition, scored it at 77 and provided some great details on the company, and it was tasty enough to make Josh Miller wax rhapsodic in 2013 when he visited the place, tried some and recommended it highly both by itself and in a Ti-punch (you need to read his 10/10 scored review as a serious counterpoint to mine and Cyril’s) – but here I have to be somewhat less enthusiastic based on my own tasting five years down the road.

(#583)(76/100)

Other notes

- Neither this rum or its lightly aged brother is listed on the St. George’s website. When I touched base with them, they sadly informed me that because of the difficulty of acquiring fresh cane, they have ceased rum production for “a number of years,” though they remain on the lookout for new and stable sources. For the moment, they’re not making any.

- An irrelevant aside to this review is that I inadvertently tried it twice: once in 2017 based on a sample sent to me (totally blind) by John Go; and the second time in 2018, this time one I bought on a whim. In both cases my tasting notes were practically identical, and so was my score. I think this is an innovative, intriguing rum from the US which can and should be tried if possible.

We don’t much associate the USA with cask strength rums, though of course they do exist, and the country has a long history with the spirit. These days, even allowing for a swelling wave of rum appreciation here and there, the US rum market seems to be primarily made up of low-end mass-market hooch from massive conglomerates at one end, and micro-distilleries of wildly varying output quality at the other. It’s the micros which interest me, because the US doesn’t do “independent bottlers” as such – they do this, and that makes things interesting, since one never knows what new and amazing juice may be lurking just around the corner, made with whatever bathtub-and-shower-nozzle-held-together-with-duct-tape distillery apparatus they’ve slapped together.

We don’t much associate the USA with cask strength rums, though of course they do exist, and the country has a long history with the spirit. These days, even allowing for a swelling wave of rum appreciation here and there, the US rum market seems to be primarily made up of low-end mass-market hooch from massive conglomerates at one end, and micro-distilleries of wildly varying output quality at the other. It’s the micros which interest me, because the US doesn’t do “independent bottlers” as such – they do this, and that makes things interesting, since one never knows what new and amazing juice may be lurking just around the corner, made with whatever bathtub-and-shower-nozzle-held-together-with-duct-tape distillery apparatus they’ve slapped together.

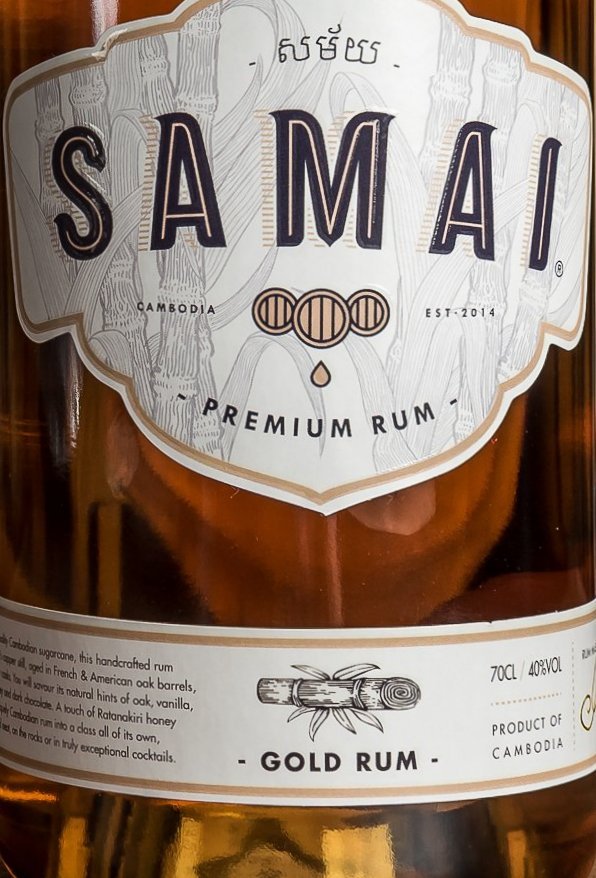

Now here’s an interesting standard-proofed gold rum I knew too little about from a country known mostly for the spectacular temples of Angor Wat and the 1970s genocide. But how many of us are aware that Cambodia was once a part of the Khmer Empire, one of the largest in South East Asia, covering much of the modern-day territories of Thailand, Vietnam, Laos and Viet Nam, or that it was once a protectorate of France, or that it is known in the east as Kampuchea?

Now here’s an interesting standard-proofed gold rum I knew too little about from a country known mostly for the spectacular temples of Angor Wat and the 1970s genocide. But how many of us are aware that Cambodia was once a part of the Khmer Empire, one of the largest in South East Asia, covering much of the modern-day territories of Thailand, Vietnam, Laos and Viet Nam, or that it was once a protectorate of France, or that it is known in the east as Kampuchea? Thailand doesn’t loom very large in the eyes of the mostly west-facing rum writers’ brigade, but just because they make it for the Asian palate and not the Euro-American cask-loving rum chums, doesn’t mean what they make can be ignored; similar in some respects to the light rums from Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic, Panama and Latin America, they may not be rums

Thailand doesn’t loom very large in the eyes of the mostly west-facing rum writers’ brigade, but just because they make it for the Asian palate and not the Euro-American cask-loving rum chums, doesn’t mean what they make can be ignored; similar in some respects to the light rums from Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic, Panama and Latin America, they may not be rums

The pattern repeated itself as I tasted it, starting off sharp, uncouth, jagged, raw…and underneath all that was some real quality. There were caramel, salty cashews, marshmallows, brown sugar (

The pattern repeated itself as I tasted it, starting off sharp, uncouth, jagged, raw…and underneath all that was some real quality. There were caramel, salty cashews, marshmallows, brown sugar (

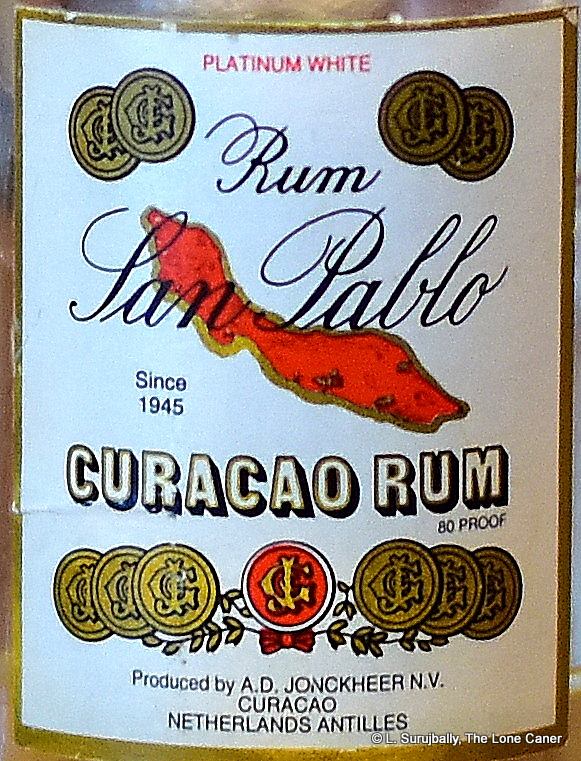

And that creates a rum of uncommon docility. In fact, it’s close to being the cheshire cat of rums, so vaguely does it present itself. The soft silky nose was a watery insignificant blend of faint nothingness. Sugar water – faint; cucumbers – faint; cane juice – faint; citrus zest – faint (in fact here I suspect the lemon was merely waved rather gravely over the barrels before being thrown away); some cumin, and it’s possible that some molasses zipped past my nose, too fast to be appreciated.

And that creates a rum of uncommon docility. In fact, it’s close to being the cheshire cat of rums, so vaguely does it present itself. The soft silky nose was a watery insignificant blend of faint nothingness. Sugar water – faint; cucumbers – faint; cane juice – faint; citrus zest – faint (in fact here I suspect the lemon was merely waved rather gravely over the barrels before being thrown away); some cumin, and it’s possible that some molasses zipped past my nose, too fast to be appreciated.

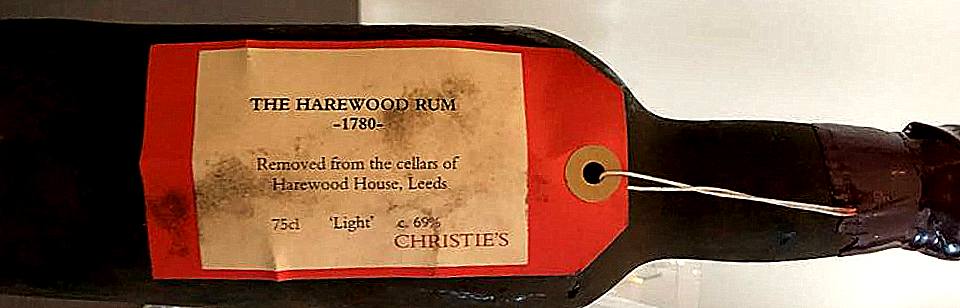

Rumaniacs Review #080 | 0516

Rumaniacs Review #080 | 0516

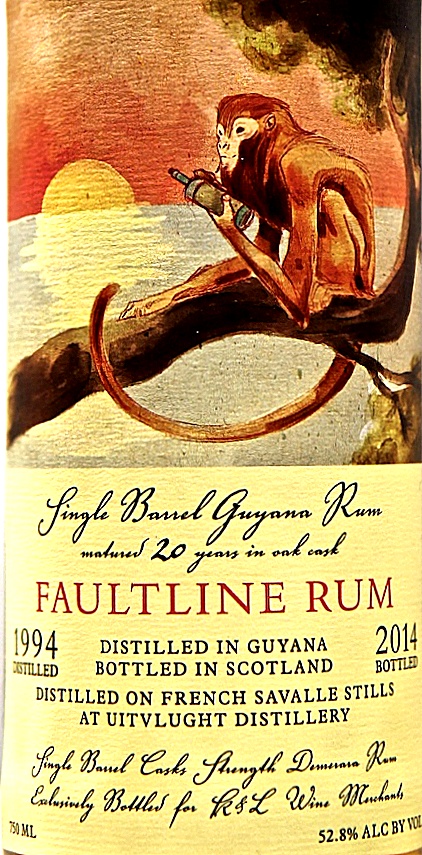

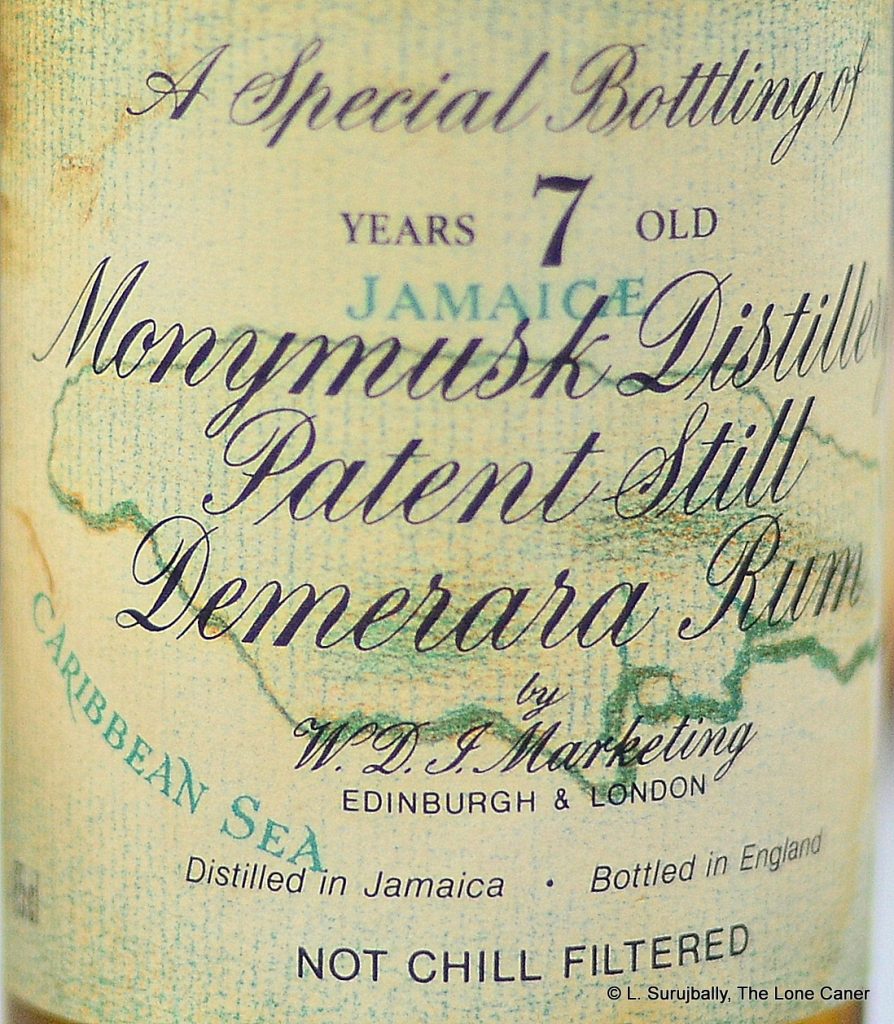

Nose – Yeah, no way this is from Mudland. The funk is all-encompassing. Overripe fruit, citrus, rotten oranges, some faint rubber, bananas that are blackened with age and ready to be thrown out. That’s what seven years gets you. Still, it’s not bad. Leave it and come back, and you’ll find additional scents of berries, pistachio ice cream and a faint hint of flowers.

Nose – Yeah, no way this is from Mudland. The funk is all-encompassing. Overripe fruit, citrus, rotten oranges, some faint rubber, bananas that are blackened with age and ready to be thrown out. That’s what seven years gets you. Still, it’s not bad. Leave it and come back, and you’ll find additional scents of berries, pistachio ice cream and a faint hint of flowers.

Say what you will about tropical ageing, there’s nothing wrong with a good long continental slumber when we get stuff like this out the other end. Again it presented as remarkably soft for the strength, allowing tastes of fruits, light licorice, vanilla, cherries, plums, and peaches to segue firmly across the tongue. Some sea salt, caramel, dates, plums, smoke and leather and a light dusting of cinnamon and florals provided additional complexity, and over all, it was really quite a good rum, closing the circle with a lovely long finish redolent of a fruit basket, port-infused cigarillos, flowers and a few extra spices.

Say what you will about tropical ageing, there’s nothing wrong with a good long continental slumber when we get stuff like this out the other end. Again it presented as remarkably soft for the strength, allowing tastes of fruits, light licorice, vanilla, cherries, plums, and peaches to segue firmly across the tongue. Some sea salt, caramel, dates, plums, smoke and leather and a light dusting of cinnamon and florals provided additional complexity, and over all, it was really quite a good rum, closing the circle with a lovely long finish redolent of a fruit basket, port-infused cigarillos, flowers and a few extra spices.

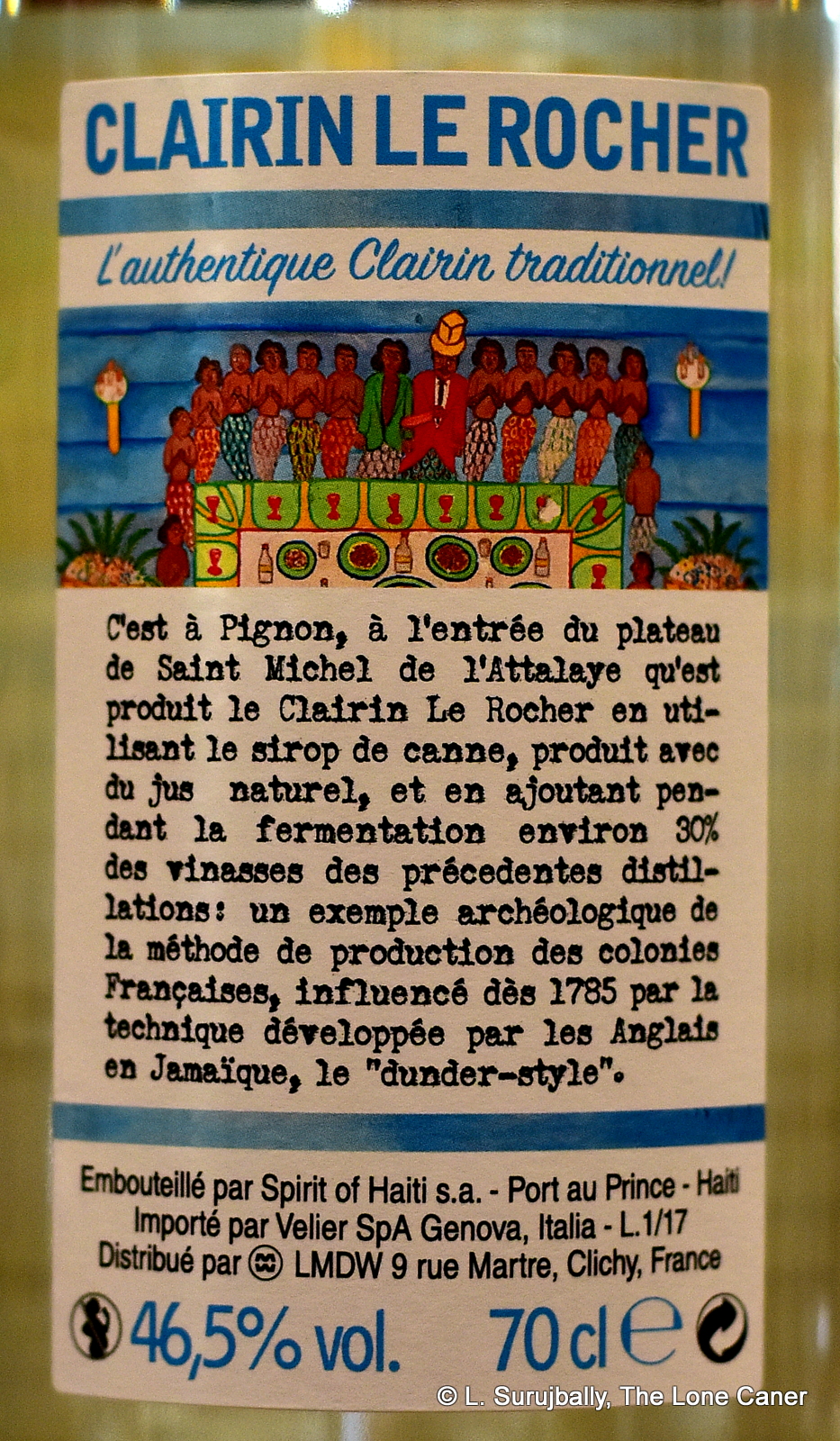

Sometimes a rum gives you a really great snooting experience, and then it falls on its behind when you taste it – the aromas are not translated well to the flavour on the palate. Not here. In the tasting, much of the richness of the nose remains, but is transformed into something just as interesting, perhaps even more complex. It’s warm, not hot or bitchy (46.5% will do that for you), remarkably easy to sip, and yes, the plasticine, glue, salt, olives, mezcal, soup and soya are there. If you wait a while, all this gives way to a lighter, finer, crisper series of flavours – unsweetened chocolate, swank, carrots(!!), pears, white guavas, light florals, and a light touch of herbs (lemon grass, dill, that kind of thing). It starts to falter after being left to stand by itself, the briny portion of the profile disappears and it gets a little bubble-gum sweet, and the finish is a little short – though still extraordinarily rich for that strength – but as it exits you’re getting a summary of all that went before…herbs, sugars, olives, veggies and a vague mineral tang. Overall, it’s quite an experience, truly, and quite tamed – the lower strength works for it, I think.

Sometimes a rum gives you a really great snooting experience, and then it falls on its behind when you taste it – the aromas are not translated well to the flavour on the palate. Not here. In the tasting, much of the richness of the nose remains, but is transformed into something just as interesting, perhaps even more complex. It’s warm, not hot or bitchy (46.5% will do that for you), remarkably easy to sip, and yes, the plasticine, glue, salt, olives, mezcal, soup and soya are there. If you wait a while, all this gives way to a lighter, finer, crisper series of flavours – unsweetened chocolate, swank, carrots(!!), pears, white guavas, light florals, and a light touch of herbs (lemon grass, dill, that kind of thing). It starts to falter after being left to stand by itself, the briny portion of the profile disappears and it gets a little bubble-gum sweet, and the finish is a little short – though still extraordinarily rich for that strength – but as it exits you’re getting a summary of all that went before…herbs, sugars, olives, veggies and a vague mineral tang. Overall, it’s quite an experience, truly, and quite tamed – the lower strength works for it, I think.