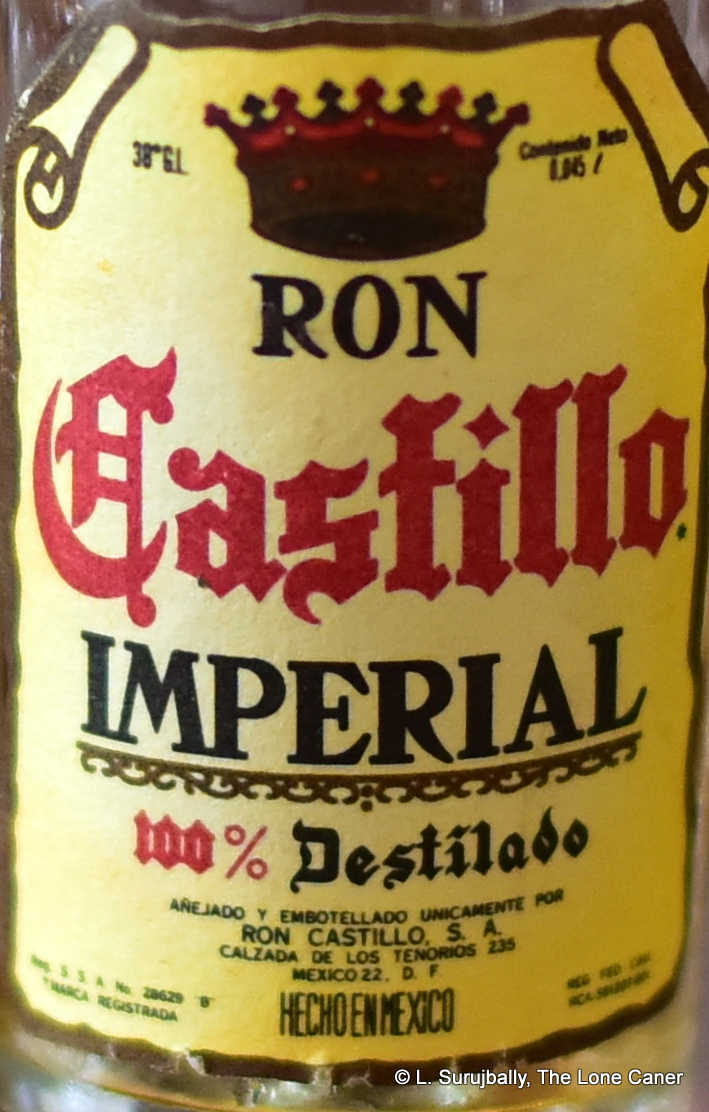

Although the unrealized flashes of interest and originality defining the Mexican Ron Caribe Silver still make it worth a buy, overall I remain at best only mildly impressed with it. Still, given the opportunity, it’s a no-brainer to try the next step up the chain, the 40% ABV standard-strength five year old Añejo Superior. After all, young aged rums tend to be introductions to the higher-end offerings of the company and be the workhorses of the establishment – solid mixing ingredients, occasionally interesting neat pours, and almost always a ladder to the premium segment (the El Dorado 5 and 8 year old rums are good examples of this).

Casa D’Aristi, about which not much can be found outside some marketing materials that can hardly be taken at face value, introduced three rums to the US market in 2017, all unlisted on its website: the silver, the 5YO and 8YO. The five year old is supposedly aged in ex bourbon barrels, and both DrunkenTiki and a helpful comment from Euros Jones-Evans on FB state that vanilla is used in its assembly (a fact unknown to me when I initially wrote my tasting notes).

This makes it a spiced or flavoured rum, and it’s at pains to demonstrate that: the extras added to the rum make themselves felt right from the beginning. The thin and vapid nose stinks of vanilla, so much so that the bit of mint, sugar water and light florals and fruits (the only things that can be picked out from underneath that nasal blanket), easily gets batted aside (and that’s saying something for a rum bottled at 40%). It’s a delicate, weak little sniff, without much going on. Except of course for vanilla.

This makes it a spiced or flavoured rum, and it’s at pains to demonstrate that: the extras added to the rum make themselves felt right from the beginning. The thin and vapid nose stinks of vanilla, so much so that the bit of mint, sugar water and light florals and fruits (the only things that can be picked out from underneath that nasal blanket), easily gets batted aside (and that’s saying something for a rum bottled at 40%). It’s a delicate, weak little sniff, without much going on. Except of course for vanilla.

This sense of the makers not trusting themselves to actually try for a decent five year old and just chucking something to jazz it up into their vats, continues when tasted. Unsurprisingly, it starts with a trumpet blast of vanilla bolted on to a thin, soft, unaggressive alcoholic water. You can, with some effort (though who would bother remains an unanswered question) detect nutmeg, watermelon, sugar water, lemon zest and a mint-chocolate, perhaps a dusting of cinnamon. And of course, more vanilla, leading to a finish that’s more of the same, whose best feature is its completely predictable and happily-quick exit.

It’s reasonably okay and a competent drink, but feels completely contrived and would be best, as Euros remarked in his note to me, for mixes and daquiris. Yes, but if that’s the case, I wish they had said what they had done and what it was made for, right there on the bottle, so I wouldn’t waste my time with such an uninspiring and insipid fake drink. What ended up happening was that I spent a whole long time while chatting with Robin Wynne (of Miss Things in Toronto) while puzzledly keeping the glass going and asking myself with every additional sip, where on earth did all the years of ageing disappear to, and why was the whole experience so much like a spiced rum? (Well yeah, I know now).

So, on balance, unhappy, unimpressed. The rum is in every way an inferior product even next to the white. I dislike it for the same reason I didn’t care for El Dorado’s 33 YO 50th Anniversary – not for its inherent lack of quality (because one meets all kinds in this world and it can be grudgingly accepted), but for the laziness with which it is made and presented, and the subterranean potential you sense that is never allowed to emerge. It’s a cop-out, and perhaps the most baffling thing about it was why they even bothered to age it for five years. They need not have wasted any time with barrels or blending or waiting, but just filtered it to within an inch of its life, stuffed it with vanilla and gotten…well, this. And I’m still not convinced they didn’t.

(#748)(72/100)

Other Notes

Since there is almost nothing on the background of the company I didn’t already mention in the review of the Silver, I won’t rehash any of it here.

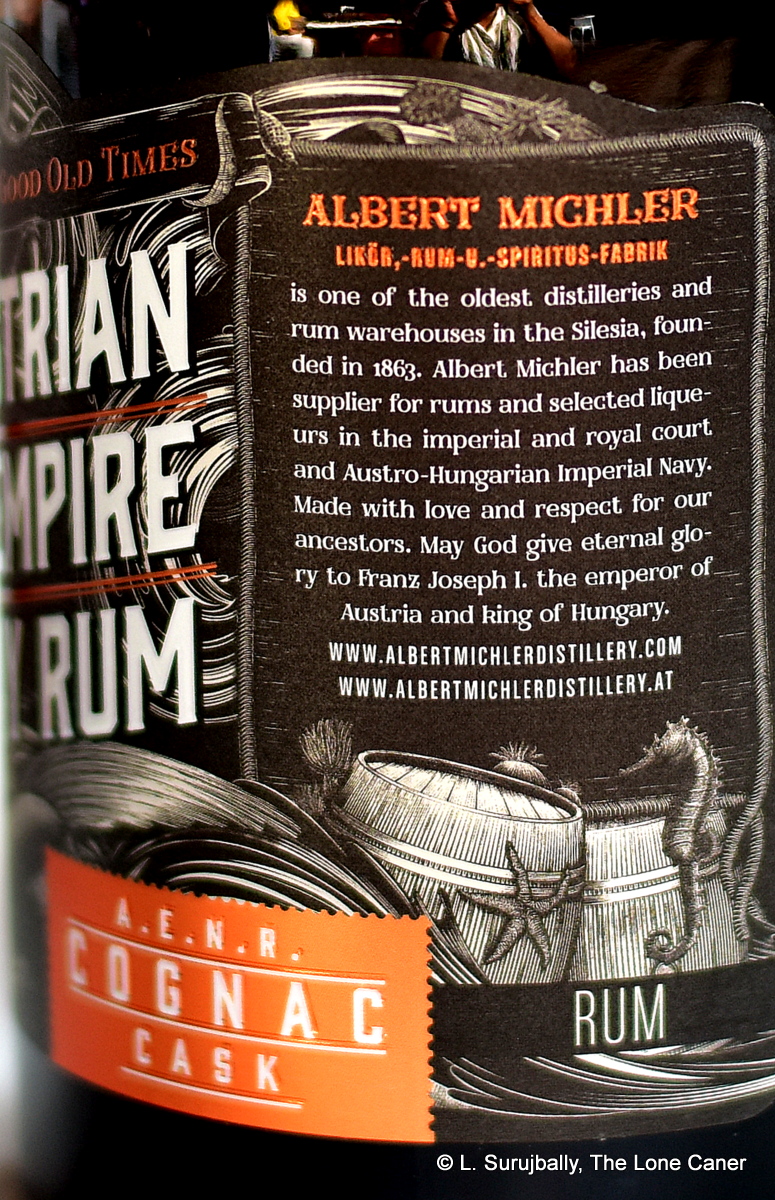

There are no records on whether the Austrian or Austro-Hungarian Navy ever used it or was supplied by the Michler distillery. Somehow I doubt it – it was far more likely it followed in the tradition of rum

There are no records on whether the Austrian or Austro-Hungarian Navy ever used it or was supplied by the Michler distillery. Somehow I doubt it – it was far more likely it followed in the tradition of rum

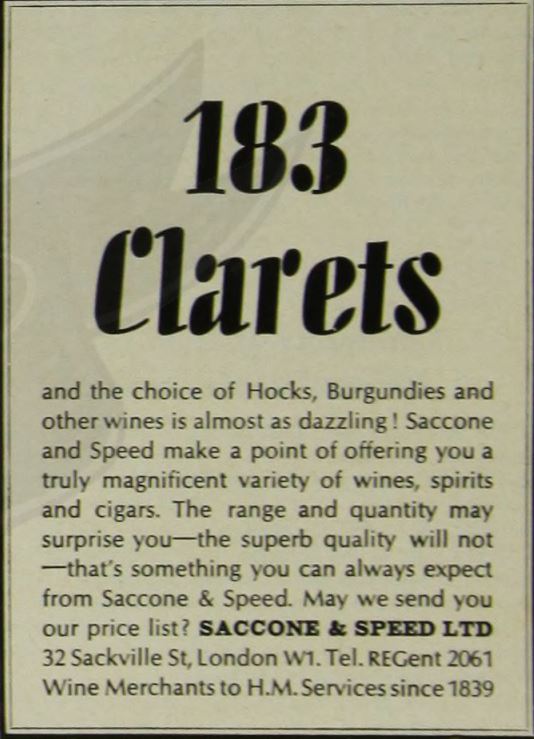

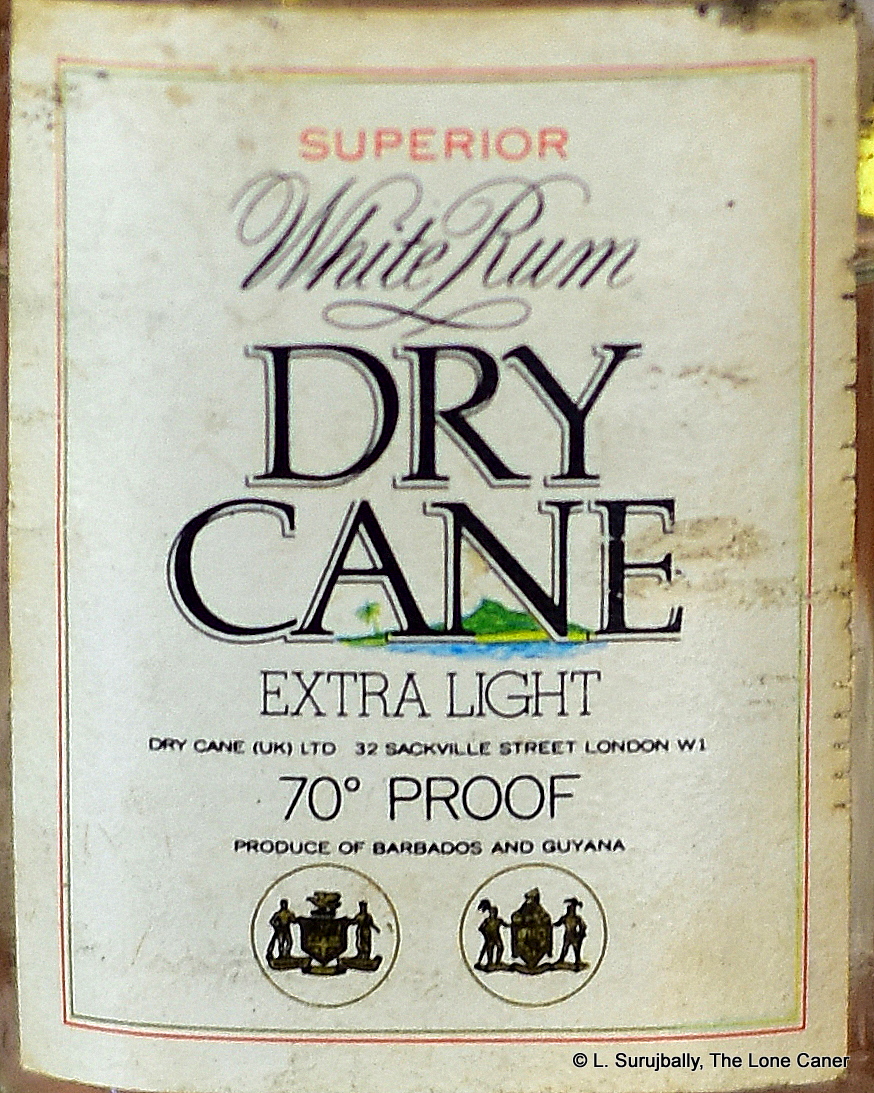

My inference is therefore that Dry Cane was a financing vehicle or shell company or wholly owned subsidiary set up for a short time to limit the exposure of the parent company (or Kinloch), as it dabbled in being an independent bottler — and just as quickly retreated, for no further products were ever made so far as I can tell. But since S&S also acquired a Gibraltar drinks franchise in 1968 and gained the concession to operate a duty free shop at Gibraltar airport in 1973, I suspect this was the rationale behind creating the rums in the first place, through the reason for its cessation is unknown. Certainly by the time S&S moved out of Sackville Street in the 1980s and to Gibraltar (where they remain to this day as part of a large conglomerate), the rum was no longer on sale.

My inference is therefore that Dry Cane was a financing vehicle or shell company or wholly owned subsidiary set up for a short time to limit the exposure of the parent company (or Kinloch), as it dabbled in being an independent bottler — and just as quickly retreated, for no further products were ever made so far as I can tell. But since S&S also acquired a Gibraltar drinks franchise in 1968 and gained the concession to operate a duty free shop at Gibraltar airport in 1973, I suspect this was the rationale behind creating the rums in the first place, through the reason for its cessation is unknown. Certainly by the time S&S moved out of Sackville Street in the 1980s and to Gibraltar (where they remain to this day as part of a large conglomerate), the rum was no longer on sale. Palate – Light and inoffensive, completely bland. Pears, sugar water, some mint. You can taste a smidgen of alcohol behind all that, it’s just that there’s nothing really serious backing it up or going on.

Palate – Light and inoffensive, completely bland. Pears, sugar water, some mint. You can taste a smidgen of alcohol behind all that, it’s just that there’s nothing really serious backing it up or going on.

Colour – Amber

Colour – Amber The Cor Cor “Green”, cousin to the

The Cor Cor “Green”, cousin to the

Given Japan has several rums which have made these pages (

Given Japan has several rums which have made these pages ( The Cor Cor Red was more generous on the palate than the nose, and as with many Japanese rums I’ve tried, it’s quite distinctive. The tastes were somewhat offbase when smelled, yet came together nicely when tasted. Most of what we might deem “traditional notes” — like nougat, or toffee, caramel, molasses, wine, dark fruits, that kind of thing — were absent; and while their (now closed) website rather honestly remarked back in 2017 that it was not for everyone, I would merely suggest that this real enjoyment is probably more for someone (a) interested in Asian rums (b) looking for something new and (c) who is cognizant of local cuisine and spirits profiles, which infuse the makers’ designs here. One of the reasons the rum tastes as it does, is because the master blender used to work for one of the awamori makers on Okinawa (it is a spirit akin to Shochu), and wanted to apply the methods of make to rum as well. No doubt some of the taste profile he preferred bled over into the final product as well.

The Cor Cor Red was more generous on the palate than the nose, and as with many Japanese rums I’ve tried, it’s quite distinctive. The tastes were somewhat offbase when smelled, yet came together nicely when tasted. Most of what we might deem “traditional notes” — like nougat, or toffee, caramel, molasses, wine, dark fruits, that kind of thing — were absent; and while their (now closed) website rather honestly remarked back in 2017 that it was not for everyone, I would merely suggest that this real enjoyment is probably more for someone (a) interested in Asian rums (b) looking for something new and (c) who is cognizant of local cuisine and spirits profiles, which infuse the makers’ designs here. One of the reasons the rum tastes as it does, is because the master blender used to work for one of the awamori makers on Okinawa (it is a spirit akin to Shochu), and wanted to apply the methods of make to rum as well. No doubt some of the taste profile he preferred bled over into the final product as well.

Colour – Light Gold

Colour – Light Gold

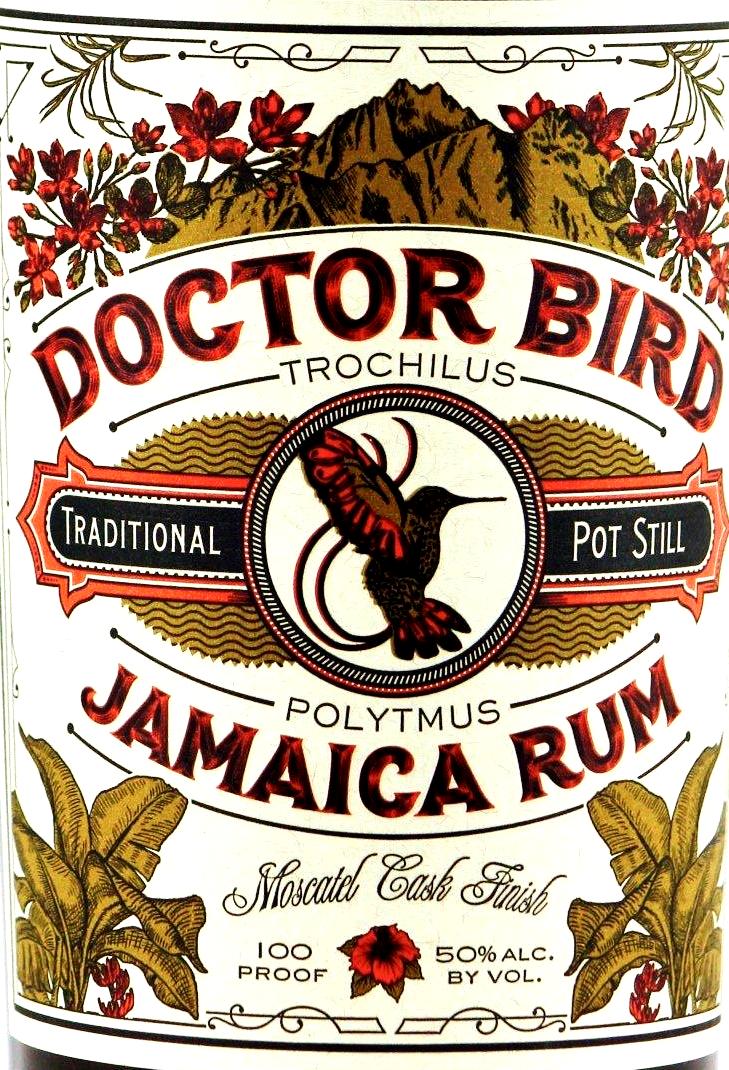

The strangely named Doctor Bird rum is another company’s response to

The strangely named Doctor Bird rum is another company’s response to

Light amber in colour and bottled at 43%, it certainly did not nose like your favoured Caribbean rum. It smelled initially of congealed honey and beeswax left to rest in an old unaired cupboard for six months – that same dusty, semi-sweet waxy and plastic odour was the most evident thing about it. Letting it rest produced additional aromas of brine, olives and ripe mangoes in a pepper sauce. Faint vanilla and caramel – was this perhaps made from jaggery, or added to after the fact? Salty cashew nuts, fruit loops cereal and that was most or less it – a fairly heavy, dusky scent, darkly sweet.

Light amber in colour and bottled at 43%, it certainly did not nose like your favoured Caribbean rum. It smelled initially of congealed honey and beeswax left to rest in an old unaired cupboard for six months – that same dusty, semi-sweet waxy and plastic odour was the most evident thing about it. Letting it rest produced additional aromas of brine, olives and ripe mangoes in a pepper sauce. Faint vanilla and caramel – was this perhaps made from jaggery, or added to after the fact? Salty cashew nuts, fruit loops cereal and that was most or less it – a fairly heavy, dusky scent, darkly sweet.

If we accept these data points, then of course the Casino is not, by all current definitions, a rum, and in point of fact, the entry might just as easily be listed in the Rumaniacs page since this version is no longer being made — the word “rum” was either replaced by “room” or dropped completely from the label when Hungary joined the EU in 2004, and that suggests a manufacture for the product I tasted of around 1988-2003 which actually makes it a heritage rum entry, but what the hell.

If we accept these data points, then of course the Casino is not, by all current definitions, a rum, and in point of fact, the entry might just as easily be listed in the Rumaniacs page since this version is no longer being made — the word “rum” was either replaced by “room” or dropped completely from the label when Hungary joined the EU in 2004, and that suggests a manufacture for the product I tasted of around 1988-2003 which actually makes it a heritage rum entry, but what the hell.

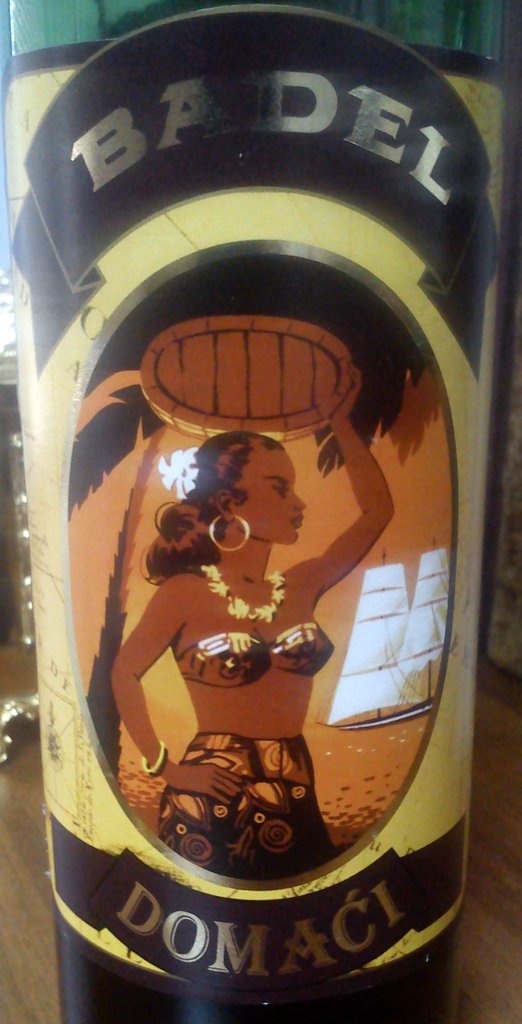

Unsurprisingly it’s mostly for sale in the Balkans — Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia, with outliers in Germany — and has made exactly zero impact on the greater rum drinking public in the West. Wes briefly touched on it with a review of

Unsurprisingly it’s mostly for sale in the Balkans — Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia, with outliers in Germany — and has made exactly zero impact on the greater rum drinking public in the West. Wes briefly touched on it with a review of

The rum was standard strength (40%), so it came as little surprise that the palate was very light, verging on airy – one burp and it was gone forever. Faintly sweet, smooth, warm, vaguely fruity, and again those minerally metallic notes could be sensed, reminding me of an empty tin can that once held peaches in syrup and had been left to dry. Further notes of vanilla, a single cherry and that was that, closing up shop with a finish that breathed once and died on the floor. No, really, that was it.

The rum was standard strength (40%), so it came as little surprise that the palate was very light, verging on airy – one burp and it was gone forever. Faintly sweet, smooth, warm, vaguely fruity, and again those minerally metallic notes could be sensed, reminding me of an empty tin can that once held peaches in syrup and had been left to dry. Further notes of vanilla, a single cherry and that was that, closing up shop with a finish that breathed once and died on the floor. No, really, that was it.

Next word: “Black”. Baby Rum Jesus help us. Long discredited as a way to classify rum, and if you are curious as to why, I refer you to

Next word: “Black”. Baby Rum Jesus help us. Long discredited as a way to classify rum, and if you are curious as to why, I refer you to

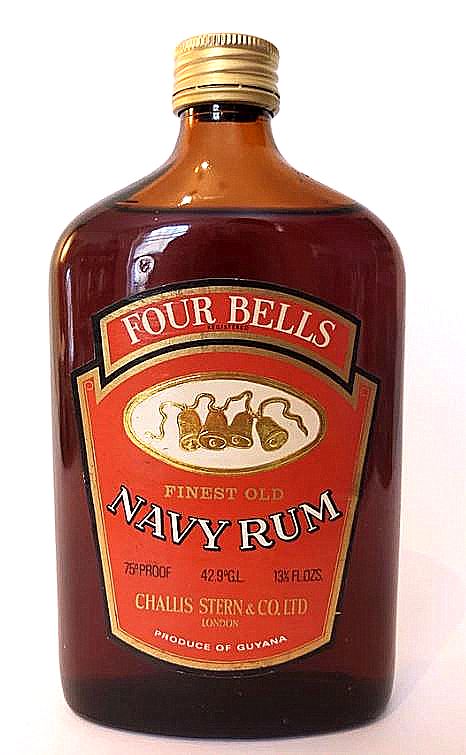

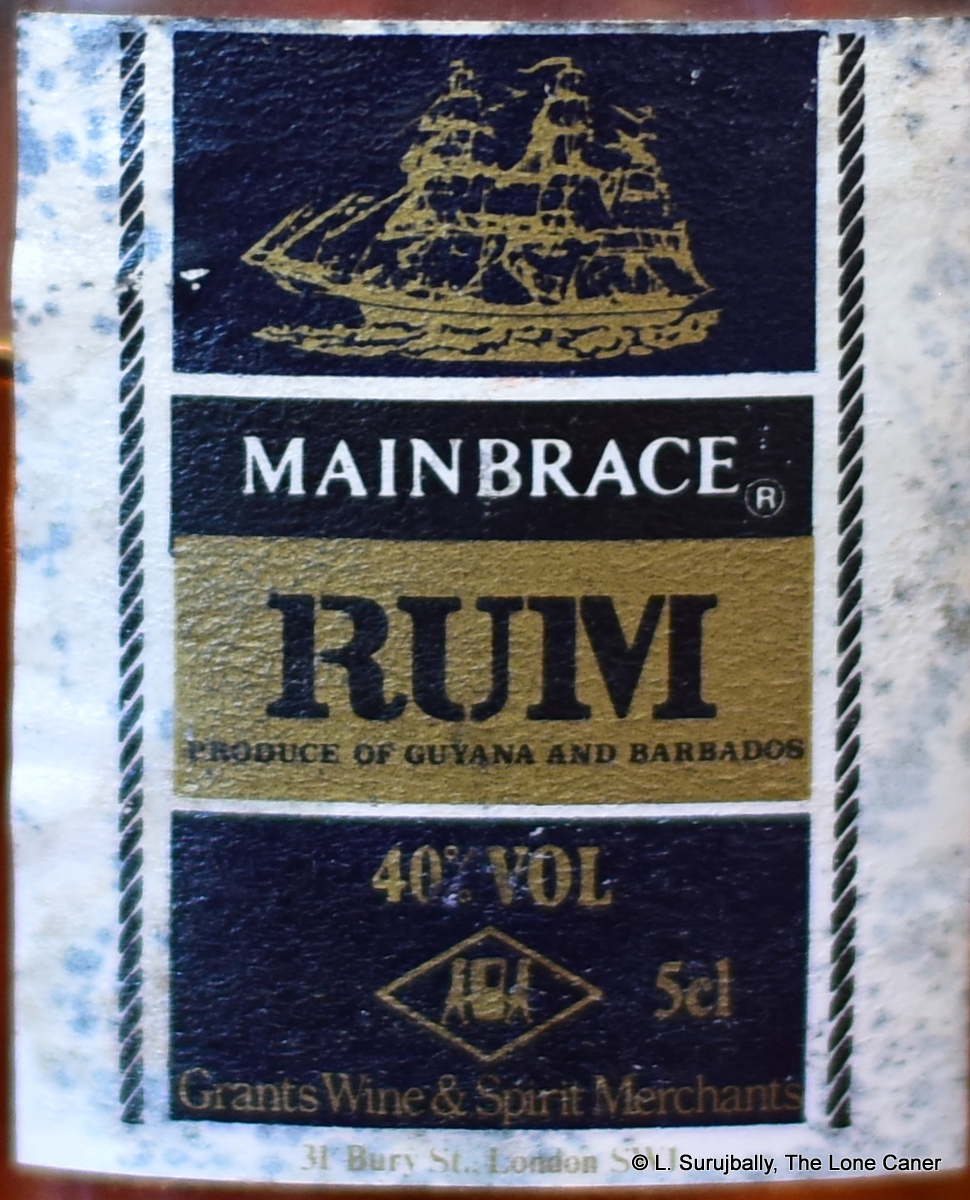

The “Guyana” spelling sets a lower post-independence date of 1966. Grants also released a Navy Rum and a Demerara Rum – both from Guyana, and both at “70º proof”. The address is written differently on their labels though, being “Grants of Saint James” on the Demerara label (Bury Lane is in the area of St. James, and a stone’s throw away from St. James’s Street…and BBR). Grants was still referring to itself as “of St. James” first (and until 1976 at least), but I think it’s the 40% ABV that’s key here, since that only came into effect in the mid 1980s in the UK.

The “Guyana” spelling sets a lower post-independence date of 1966. Grants also released a Navy Rum and a Demerara Rum – both from Guyana, and both at “70º proof”. The address is written differently on their labels though, being “Grants of Saint James” on the Demerara label (Bury Lane is in the area of St. James, and a stone’s throw away from St. James’s Street…and BBR). Grants was still referring to itself as “of St. James” first (and until 1976 at least), but I think it’s the 40% ABV that’s key here, since that only came into effect in the mid 1980s in the UK.