Speaking in general terms, my personal drift away from Latin- or South American rums over the last few years derives from the feeling that they’re a little too laid back, and lack pizzazz. They’re not bad, just placid and easy going and gentle, and when you add to that the disclosure issues, you can perhaps understand why I’ve moved on to more interesting profiles.

Far too many producers from the region do too much unadventurous blending (Canalero), don’t actually have a true solera in play (Dictador), have a thing for light column still products which may or may not be tarted up (Panama Red), and are resting on the laurels of old houses and family recipes (Maya) whose provenance can hardly be established beyond a shadow of doubt (Mombacho or Hechicera). Moreover, there is too often a puzzling lack of easily-available background regarding such rums (more than just marketing materials) which is out of step with the times.

Still, I have to be careful to not paint with too wide a brush – there are many good rums from the region and I’m not displeased with all of them. In a curious turnabout, my favourites are not always released by from or by Latin American companies — at least, not directly — but by independents who take the original distillate from a broker and then release it as is. This avoids some of the pitfalls of indeterminate blending, additives, dilution and source, because you can pretty much count on a small indie outfit to tell you everything they themselves know about what they stuffed into their bottle.

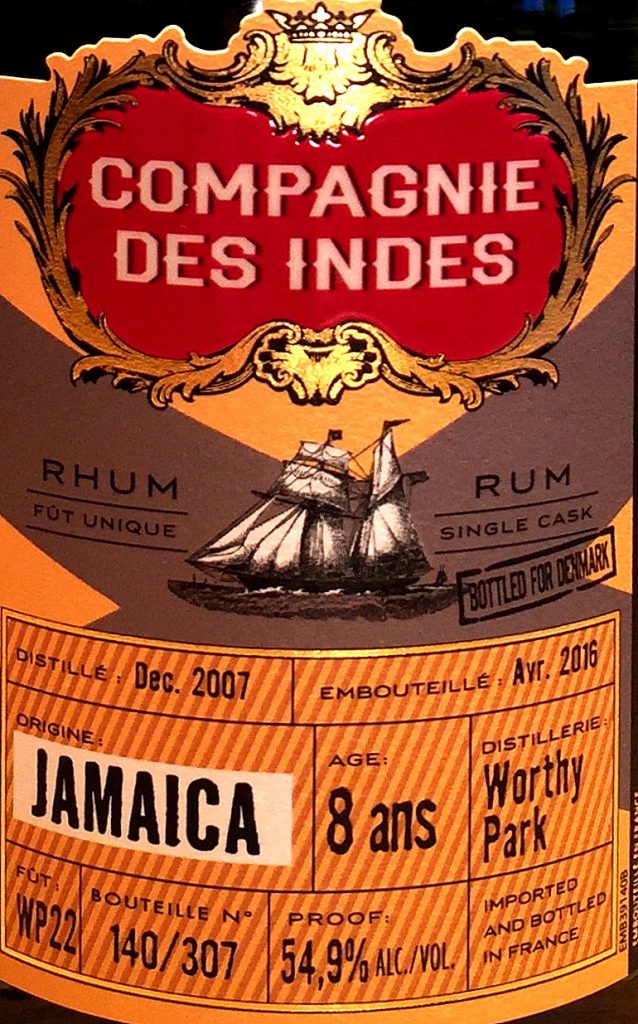

That’s not to say that in this case the Compagnie is a poster child for such disclosure – the distillery on this one is noted as being “Secret”, for example. But I suspect that Florent was a bit tongue in cheek here, since any reasonably knowledgeable anorak can surmise that the 11 YO rum being reviewed here is a Flor de Cana distillate, column still, and aged in Europe.

That’s not to say that in this case the Compagnie is a poster child for such disclosure – the distillery on this one is noted as being “Secret”, for example. But I suspect that Florent was a bit tongue in cheek here, since any reasonably knowledgeable anorak can surmise that the 11 YO rum being reviewed here is a Flor de Cana distillate, column still, and aged in Europe.

Compared to the Mombacho 1989 that was being tried alongside it (and about which I still know too little), the nose was much more interesting – perhaps this was because the Compagnie didn’t mess around with a soft 43%, but went full bore at 69.1% for their favoured clients, the Danes (this rum is for the Danish market). Yet for all the strength, it presented as almost delicate — light, fruity (pears, guavas, watermelon., papaya), with a nice citrus tang running through it. When it opened up some more, I also smelled apples, pears, honey, cherries in syrup, and a pleasant deeper scent of aromatic tobacco, oak and smoke, and a touch of vanilla at the back end.

The palate was also very robust (to say the least). It was sharp, but not raw – some of the rougher edges had been toned down somewhat – and gave off rich tastes of honey, stewed apples, more sweet tobacco and smoke, all of it dripping with vanilla. Those light fruits evident on the nose were somewhat overpowered by the strength, yet one could still pick out some cherries and peaches and apples, leading into a very long and highly enjoyable finish with closing notes of gherkins, brine, cereals, vanilla, and a last flirt of light sweet fruits.

Perhaps it was a mistake to try that supposed 19 YO Mombacho together with this independent offering from France. On the face of it they’re similar, both from Nicaragua and both aged a fair bit — but it’s in the details (and the sampling) that the differences snap more clearly into focus, and show how the independents deserve, and are given, quite a bit more trust than some low-key company which is long on hyperbole and short on actual facts.

As noted above, neither company says from which distillery its rums hail, though of course I’m sure they’re Flor de Cana products, both of them. We don’t know where Mombacho ages its barrels; CDI can safely be assumed to be Europe. The CDI is stronger, is more intense and simply tastes better, versus the much softer and easier (therefore relatively unchallenging) Mombacho, even if it lacks the latter’s finish in armagnac casks. Beyond that, we get rather more from the Compagnie – barrel number, date of distillation and bottling, true age, plus a little extra – the faith, built up over many years of limited bottlings, that we’re getting what they tell us we are, and the confidence that it’s true. That alone allowed me to relax and enjoy the rum much more than might otherwise have been the case.

(#593)(84.5/100)

Other notes

- Controls this time around were the aforementioned Mombacho, the Black Adder 12YO, and another Nicaraguan from CDI, aged for seventeen years. I dipped in and out of the sample cabinet for the comparators mentioned in the first paragraph — not to re-evaluate them, just to get a sense of their profiles as opposed to this one.

- Distilled December 2004, bottled April 2016, 242 bottle-outturn

- We should not read too much into the “Secret” appellation for the rum’s source. Sometimes, companies have a clause in their bulk rum sales contracts that forbids a third party re-bottler (i.e., an independent) from mentioning the distillery of origin.

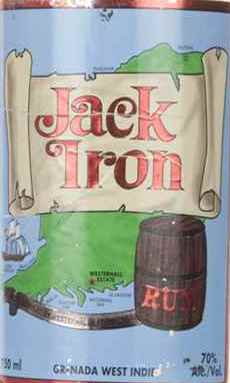

The Jack Iron rum from Westerhall is a booming overproof issued both in a slightly aged and a white version, and both are a whopping 70% ABV. While you can get it abroad — this bottle was tried in Italy, for example — my take is that it’s primarily a rum for local consumption (though which island can lay claim to it is a matter of idle conjecture), issued to paralyze brave-but-foolhardy tourists who want to show off their Chewbacca chests by drinking it neat, or to comfort the locals who don’t have time to waste getting hammered and just want to do it quick time. Add to that the West Indian slang for manly parts occasionally being iron and you can sense a sort of cheerful and salty islander sense of humour at work (see “other notes” below for an alternative backstory).

The Jack Iron rum from Westerhall is a booming overproof issued both in a slightly aged and a white version, and both are a whopping 70% ABV. While you can get it abroad — this bottle was tried in Italy, for example — my take is that it’s primarily a rum for local consumption (though which island can lay claim to it is a matter of idle conjecture), issued to paralyze brave-but-foolhardy tourists who want to show off their Chewbacca chests by drinking it neat, or to comfort the locals who don’t have time to waste getting hammered and just want to do it quick time. Add to that the West Indian slang for manly parts occasionally being iron and you can sense a sort of cheerful and salty islander sense of humour at work (see “other notes” below for an alternative backstory).

And for anyone who enjoys sipping rich Jamaicans that don’t stray too far into insanity (the

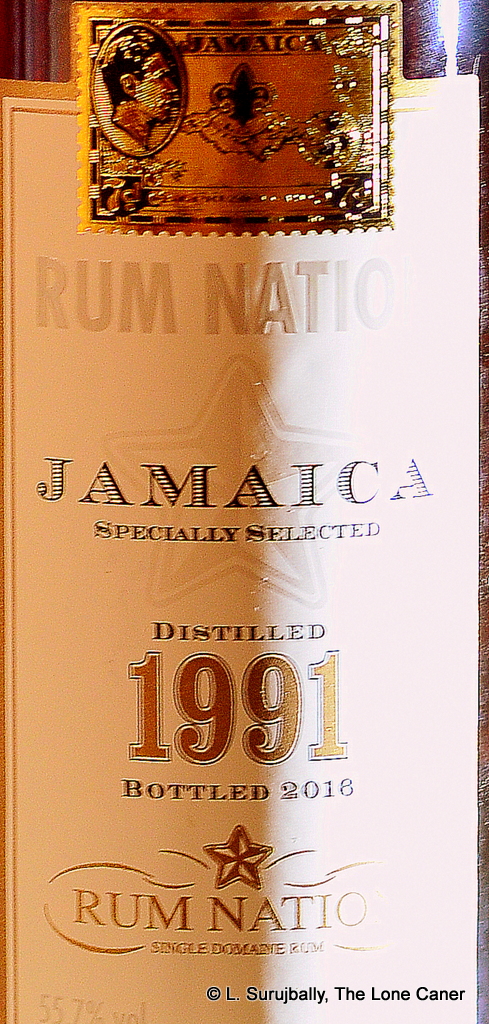

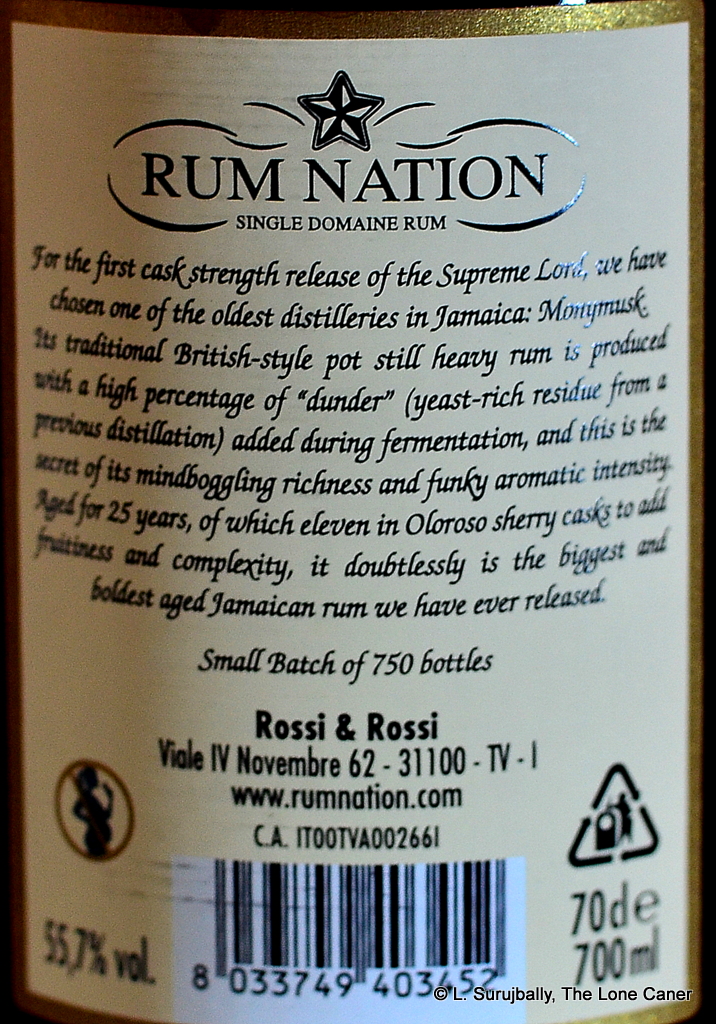

And for anyone who enjoys sipping rich Jamaicans that don’t stray too far into insanity (the  The rum continues along the path set by all the seven Supreme Lords that came before it, and since I’ve not tried them all, I can’t say whether others are better, or if this one eclipses the lot. What I do know is that they are among the best series of Jamaican rums released by any independent, among the oldest, and a key component of my own evolving rum education.

The rum continues along the path set by all the seven Supreme Lords that came before it, and since I’ve not tried them all, I can’t say whether others are better, or if this one eclipses the lot. What I do know is that they are among the best series of Jamaican rums released by any independent, among the oldest, and a key component of my own evolving rum education.

This brings us to the

This brings us to the

Because for the unprepared (as I was), the nose of this rum is edging right up against revolting. It’s raw, rotting meat mixed with wet fruity garbage distilled into your rum glass without any attempt at dialling it down (except perhaps to 40% which is a small mercy). It’s like a lizard that died alone and unnoticed under your workplace desk and stayed there, was then soaked in diesel, drizzled with molten rubber and tar, set afire and then pelted with gray tomatoes. That thread of rot permeates every aspect of the nose – the brine and olives and acetone/rubber smell, the maggi cubes, the hot vegetable soup and lemongrass…everything.

Because for the unprepared (as I was), the nose of this rum is edging right up against revolting. It’s raw, rotting meat mixed with wet fruity garbage distilled into your rum glass without any attempt at dialling it down (except perhaps to 40% which is a small mercy). It’s like a lizard that died alone and unnoticed under your workplace desk and stayed there, was then soaked in diesel, drizzled with molten rubber and tar, set afire and then pelted with gray tomatoes. That thread of rot permeates every aspect of the nose – the brine and olives and acetone/rubber smell, the maggi cubes, the hot vegetable soup and lemongrass…everything. Just as we don’t see Americans making too many full proof rums, it’s also hard to see them making true agricoles, especially since the term is so tightly bound up with the spirits of the French islands.

Just as we don’t see Americans making too many full proof rums, it’s also hard to see them making true agricoles, especially since the term is so tightly bound up with the spirits of the French islands.

We don’t much associate the USA with cask strength rums, though of course they do exist, and the country has a long history with the spirit. These days, even allowing for a swelling wave of rum appreciation here and there, the US rum market seems to be primarily made up of low-end mass-market hooch from massive conglomerates at one end, and micro-distilleries of wildly varying output quality at the other. It’s the micros which interest me, because the US doesn’t do “independent bottlers” as such – they do this, and that makes things interesting, since one never knows what new and amazing juice may be lurking just around the corner, made with whatever bathtub-and-shower-nozzle-held-together-with-duct-tape distillery apparatus they’ve slapped together.

We don’t much associate the USA with cask strength rums, though of course they do exist, and the country has a long history with the spirit. These days, even allowing for a swelling wave of rum appreciation here and there, the US rum market seems to be primarily made up of low-end mass-market hooch from massive conglomerates at one end, and micro-distilleries of wildly varying output quality at the other. It’s the micros which interest me, because the US doesn’t do “independent bottlers” as such – they do this, and that makes things interesting, since one never knows what new and amazing juice may be lurking just around the corner, made with whatever bathtub-and-shower-nozzle-held-together-with-duct-tape distillery apparatus they’ve slapped together.

Oh yes…though it is different – some might even sniff and say “Well, it isn’t Foursquare,” and walk away, leaving more for me to acquire, but never mind. The thing is, it carved out its own olfactory niche, distinct from both its older brother and better known juice from St. Phillip. It was warm, almost but not quite spicy, and opened with aromas of biscuits, crackers, hot buns fresh from the oven, sawdust, caramel and vanilla, before exploding into a cornucopia of cherries, ripe peaches and delicate flowers, and even some sweet bubble gum. In no way was it either too spicy or too gentle, but navigated its way nicely between both.

Oh yes…though it is different – some might even sniff and say “Well, it isn’t Foursquare,” and walk away, leaving more for me to acquire, but never mind. The thing is, it carved out its own olfactory niche, distinct from both its older brother and better known juice from St. Phillip. It was warm, almost but not quite spicy, and opened with aromas of biscuits, crackers, hot buns fresh from the oven, sawdust, caramel and vanilla, before exploding into a cornucopia of cherries, ripe peaches and delicate flowers, and even some sweet bubble gum. In no way was it either too spicy or too gentle, but navigated its way nicely between both.

To be honest, the initial nose reminds me rather more of a Guyanese Uitvlugt, which, given the still of origin, may not be too far out to lunch. Still, consider the aromas: they were powerful yet light and very clear – caramel and pancake syrup mixed with brine, vegetable soup, and bags of fruits like raspberries, strawberries, red currants. Wrapped up within all that was vanilla, cinnamon, cloves, cumin, and light citrus peel. Honestly, the assembly was so good that it took effort to remember it was bottled at a hefty 66% (and wasn’t from Uitvlugt).

To be honest, the initial nose reminds me rather more of a Guyanese Uitvlugt, which, given the still of origin, may not be too far out to lunch. Still, consider the aromas: they were powerful yet light and very clear – caramel and pancake syrup mixed with brine, vegetable soup, and bags of fruits like raspberries, strawberries, red currants. Wrapped up within all that was vanilla, cinnamon, cloves, cumin, and light citrus peel. Honestly, the assembly was so good that it took effort to remember it was bottled at a hefty 66% (and wasn’t from Uitvlugt).

Rumaniacs Review #087 | 0574

Rumaniacs Review #087 | 0574