Hampden gets so many kudos these days from its relationship with Velier — the slick marketing, the yellow boxes, the Endemic Bird series, the great tastes, the sheer range of them all — that to some extent it seems like Worthy Park is the poor red haired stepchild of the glint in the milkman’s eye, running behind dem Big Boy picking up footprints. Yet Worthy Park is no stranger to really good rums of its own, also pot still made, and clearly distinguishable to one who loves the New Jamaicans. They are not just any Jamaicans…they’re Worthy Park, dammit. They have no special relationship with anyone, and don’t really want (or need) one.

Hampden gets so many kudos these days from its relationship with Velier — the slick marketing, the yellow boxes, the Endemic Bird series, the great tastes, the sheer range of them all — that to some extent it seems like Worthy Park is the poor red haired stepchild of the glint in the milkman’s eye, running behind dem Big Boy picking up footprints. Yet Worthy Park is no stranger to really good rums of its own, also pot still made, and clearly distinguishable to one who loves the New Jamaicans. They are not just any Jamaicans…they’re Worthy Park, dammit. They have no special relationship with anyone, and don’t really want (or need) one.

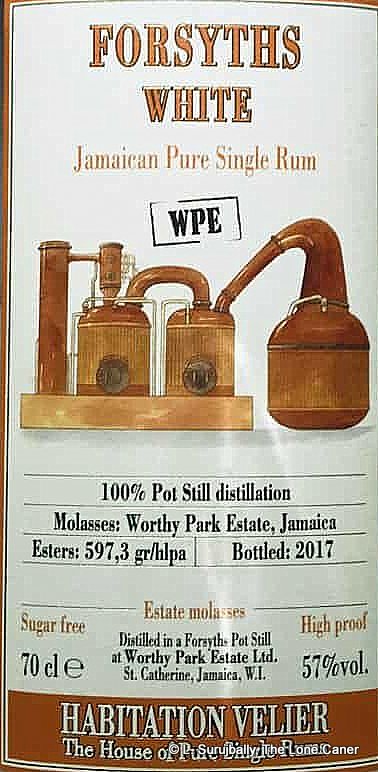

For a long time, until around 2005, Worthy Park was either closed or distilling rum for bulk export, but in that year they restarted distilling on their double retort pot still and in 2013 Luca Gargano, the boss of Velier, came on a tour of Jamaica and took note. By 2016 when he released the first series of the Habitation Velier line (using 2015 distillates) he was able to convince WP to provide him with three rums, and in 2017 he got three more. This one was a special edition of sorts from that second set, using an extended fermentation period – three months! – to develop a higher ester count than usual (597.3 g/hLpa, the label boasts). It was issued as an unaged 57% white, and let me tell you, it takes its place proudly among the pantheon of such rums with no apology whatsoever.

I make that statement with no expectation of a refutation. The rum doesn’t just leap out of the bottle to amaze and astonish, it detonates, as if the Good Lord hisself just gave vent to a biblical flatus. You inhale rotting fruit, rubber tyres and banana skins, a pile of warm sweet garbage left to decompose in the topical sun after being half burnt and then extinguished by a short rain. It mixes up the smell of sweet dark overripe cherries with the peculiar aroma of the ink in a fountain pen. It’s musty, it’s mucky, it’s thick with sweet Indian spices, possesses a clear burn that shouldn’t be pleasant but is, and it may still, after all this time, be one of the most original rums you’ve tried this side of next week. When you catch your breath after a long sniff, that’s the sort of feeling you’re left with.

Oh and it’s clear that WP and their master blender aren’t satisfied with just having a certifiable aroma that would make a DOK (and the Caner) weep, but are intent on amping up the juice to “12”. The rum is hot-snot and steel-solid, with the salty and oily notes of a pot still hooch going full blast. There’s the taste of wax, turpentine, salt, gherkins, sweet thick soya sauce, and if this doesn’t stretch your imagination too far, petrol and burnt rubber mixed with the sugar water. Enough? “No, mon,” you can hear them say as they tweak it some more, “Dis ting still too small.” And it is, because when you wait, you also get brine, sweet red olives, paprika, pineapple, ripe mangoes, soursop, all sweetness and salt and fruits, leading to a near explosive conclusion that leaves the taste buds gasping. Bags of fruit and salt and spices are left on the nose, the tongue, the memory and with its strength and clear, glittering power, it would be no exaggeration to remark that this is a rum which dark alleyways are afraid to have walk down it.

The rum displays all the attributes that made the estate’s name after 2016 when they started supplying their rums to others and began bottling their own. It’s a rum that’s astonishingly stuffed with tastes from all over the map, not always in harmony but in a sort of cheerful screaming chaos that shouldn’t work…except that it does. More sensory impressions are expended here than in any rum of recent memory (and I remember the TECA) and all this in an unaged rum. It’s simply amazing.

The rum displays all the attributes that made the estate’s name after 2016 when they started supplying their rums to others and began bottling their own. It’s a rum that’s astonishingly stuffed with tastes from all over the map, not always in harmony but in a sort of cheerful screaming chaos that shouldn’t work…except that it does. More sensory impressions are expended here than in any rum of recent memory (and I remember the TECA) and all this in an unaged rum. It’s simply amazing.

If you want to know why I’m so enthusiastic, well, it’s because I think it really is that good. But also, in a time of timid mediocrity where too many rum makers (like those Panamanians I was riffing about last week) are afraid to take a chance, I like ambitious rum makers who go for broke, who litter rum blogs, rumfest floors and traumatized palates with the detritus of their failures, who leave their outlines in the walls they run into (and through) at top speed. I like their ambition, their guts, their utter lack of fear, the complete surrender to curiosity and the willingness to go down any damned experimentative rabbit hole they please. I don’t score this in the nineties, but God, I do admire it – give me a rum that bites off more than it can chew, any time, over milquetoast low-strength yawn-through that won’t even try gumming it.

(#790)(86/100)

Other notes

- Outturn unknown.

- The Habitation Velier WP 2017 “151” edition was also a WPE and from this same batch (the ester counts are the same).

- In the marque “WPE” the WP is self explanatory, and the “E” stands for “Ester”

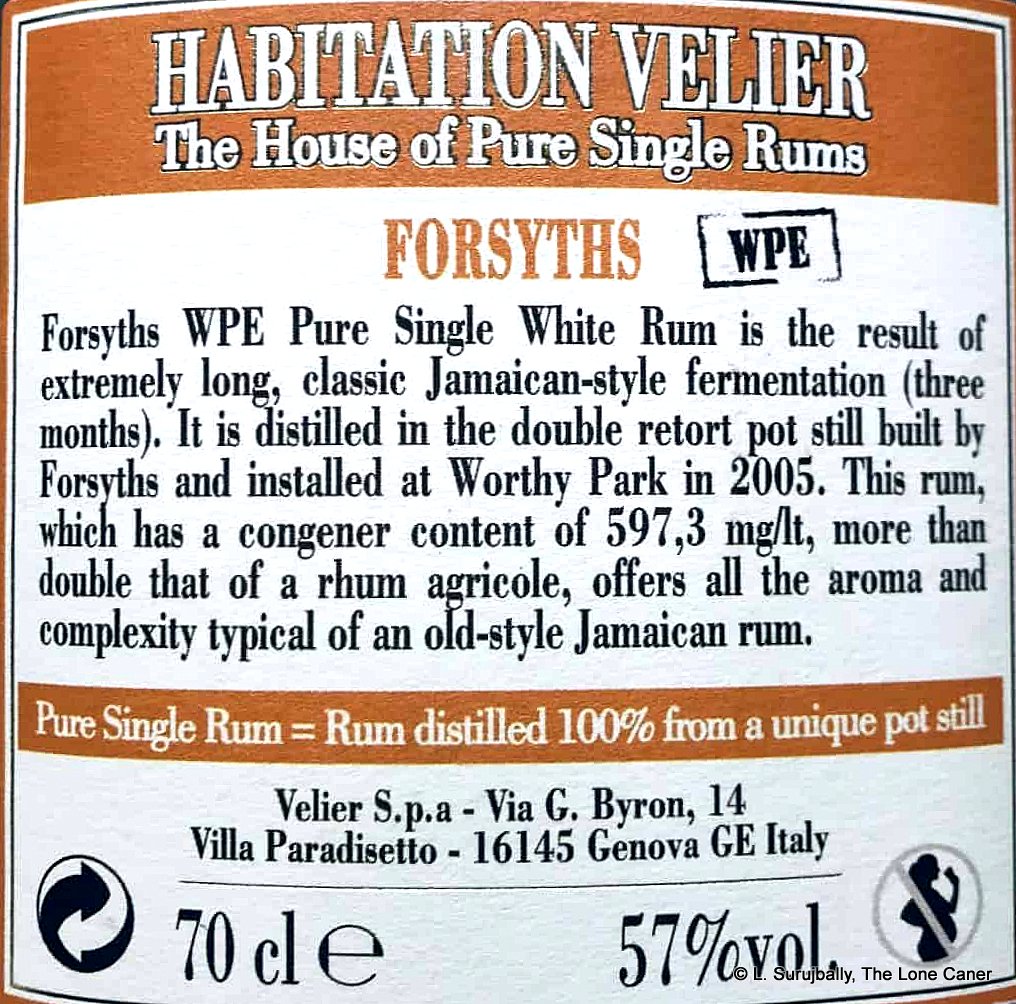

In spite of the high ABV, which lends a fair amount of initial sharpness and heat to the tongue until it burns away and settles down, it’s actually not that fierce. It becomes almost delicate, and there’s a nice vein of fruity sweetness running through, which enhances the flavours of apples, cider, green grapes, citrus, coconut, vanilla, and candied oranges. There’s also some of that polish and acetone remaining, neatly dampened by caramel and brown sugar, all balancing off well against each other. It retains that delicacy to the finish line and stays well behaved: a touch sweet throughout, with caramel (a bit much), vanilla, fruits, grapes, raisins, citrus, blancmange…not bad at all.

In spite of the high ABV, which lends a fair amount of initial sharpness and heat to the tongue until it burns away and settles down, it’s actually not that fierce. It becomes almost delicate, and there’s a nice vein of fruity sweetness running through, which enhances the flavours of apples, cider, green grapes, citrus, coconut, vanilla, and candied oranges. There’s also some of that polish and acetone remaining, neatly dampened by caramel and brown sugar, all balancing off well against each other. It retains that delicacy to the finish line and stays well behaved: a touch sweet throughout, with caramel (a bit much), vanilla, fruits, grapes, raisins, citrus, blancmange…not bad at all.

Or so the story-teller in me supposes. Because all jokes and anecdotes aside, what this is, is a rum made to order.

Or so the story-teller in me supposes. Because all jokes and anecdotes aside, what this is, is a rum made to order.

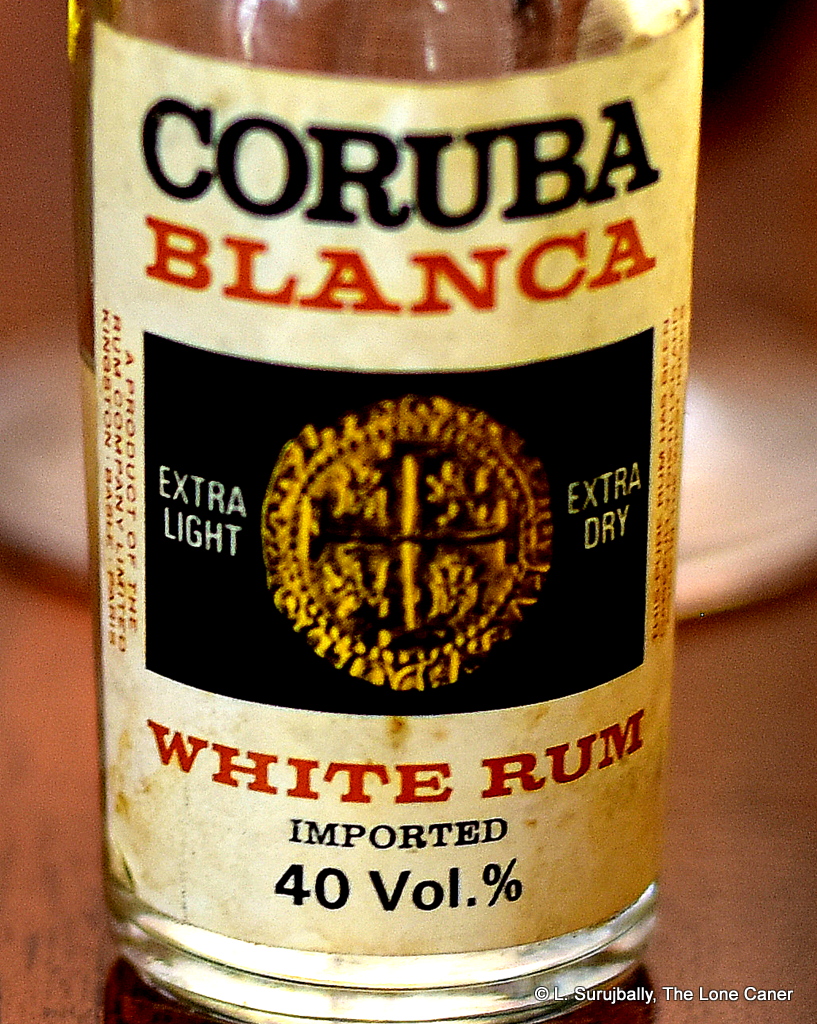

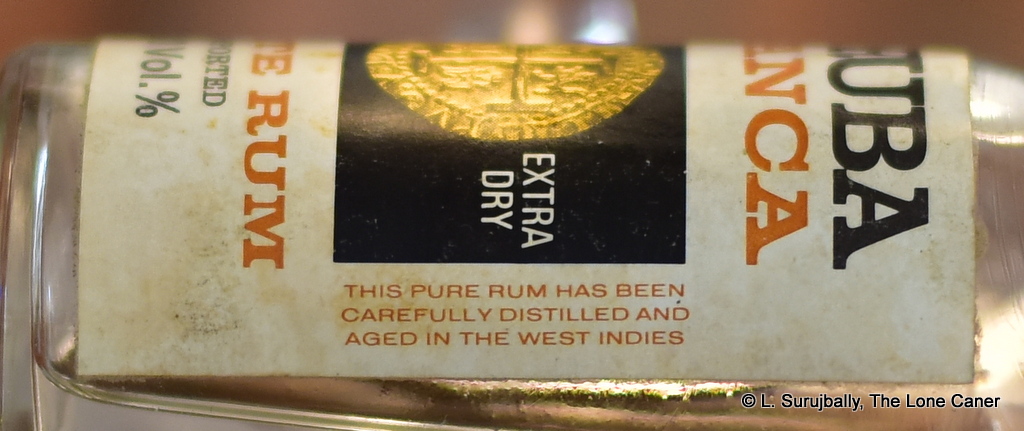

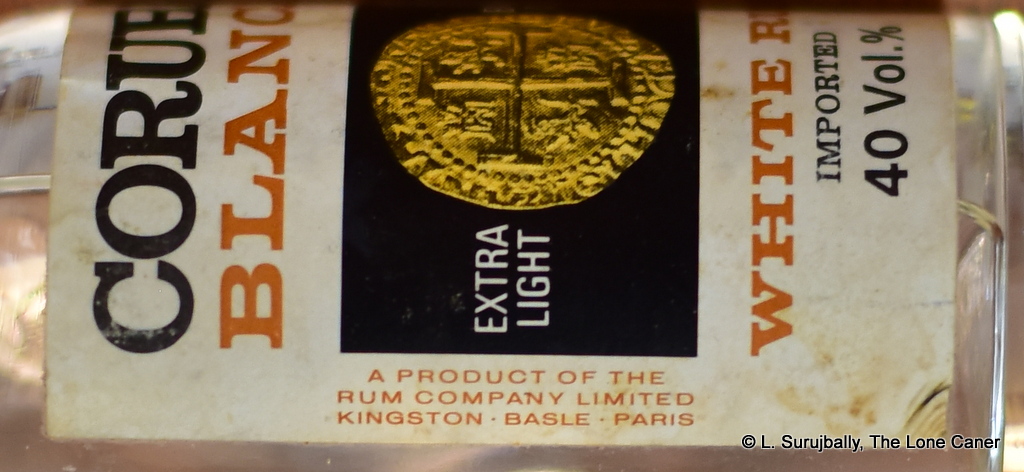

The nose begins with metallic, ashy notes right away, damp cardboard in a long-abandoned, leaky musty house. Thankfully this peculiar aroma doesn’t hang around, but morphs into a sort of soya-salt veggie soup vibe, which in turn gets muskier and sweeter over time; it releases notes of bananas and molasses and syrup, before gradually lightening and becoming – surprisingly enough – rather crisp. White fruits emerge – unripe pears and guavas, green apples, gooseberries, grapes. What’s really surprising is the way this all transforms over a period of ten minutes or so from one nasal profile to another. It’s not usual, but it is noteworthy.

The nose begins with metallic, ashy notes right away, damp cardboard in a long-abandoned, leaky musty house. Thankfully this peculiar aroma doesn’t hang around, but morphs into a sort of soya-salt veggie soup vibe, which in turn gets muskier and sweeter over time; it releases notes of bananas and molasses and syrup, before gradually lightening and becoming – surprisingly enough – rather crisp. White fruits emerge – unripe pears and guavas, green apples, gooseberries, grapes. What’s really surprising is the way this all transforms over a period of ten minutes or so from one nasal profile to another. It’s not usual, but it is noteworthy. Rumaniacs Review #122 | 0785

Rumaniacs Review #122 | 0785

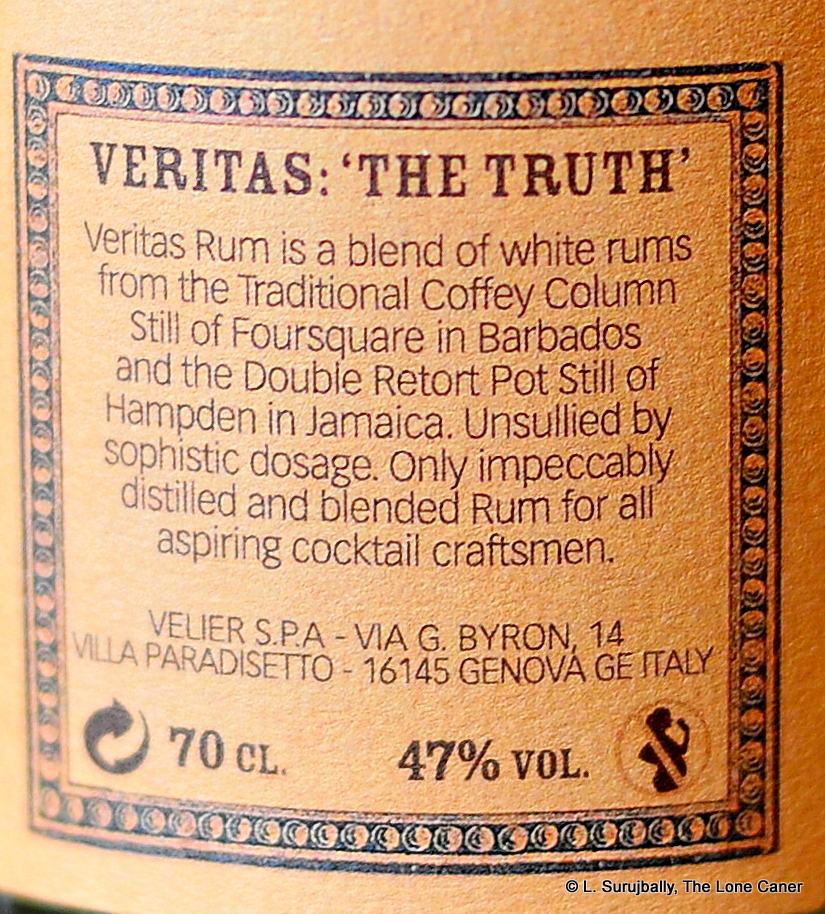

When it really comes down to it, the only thing I didn’t care for is the name. It’s not that I wanted to see “Jamados” or “Bamaica” on a label (one shudders at the mere idea) but I thought “Veritas” was just being a little too hamfisted with respect to taking a jab at Plantation in the ongoing feud with Maison Ferrand (the statement of “unsullied by sophistic dosage” pointed there). As it turned out, my opinion was not entirely justified, as Richard Seale noted in a comment to to me that… “It was intended to reflect the simple nature of the rum – free of (added) colour, sugar or anything else including at that time even addition from wood. The original idea was for it to be 100% unaged. In the end, when I swapped in aged pot for unaged, it was just markedly better and just ‘worked’ for me in the way the 100% unaged did not.” So for sure there was more than I thought at the back of this title.

When it really comes down to it, the only thing I didn’t care for is the name. It’s not that I wanted to see “Jamados” or “Bamaica” on a label (one shudders at the mere idea) but I thought “Veritas” was just being a little too hamfisted with respect to taking a jab at Plantation in the ongoing feud with Maison Ferrand (the statement of “unsullied by sophistic dosage” pointed there). As it turned out, my opinion was not entirely justified, as Richard Seale noted in a comment to to me that… “It was intended to reflect the simple nature of the rum – free of (added) colour, sugar or anything else including at that time even addition from wood. The original idea was for it to be 100% unaged. In the end, when I swapped in aged pot for unaged, it was just markedly better and just ‘worked’ for me in the way the 100% unaged did not.” So for sure there was more than I thought at the back of this title.

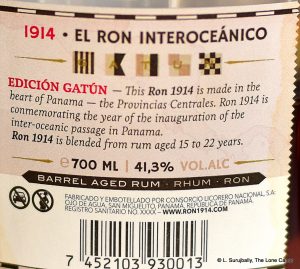

This process provides a tasting profile that reminds me of nothing so much than a slightly addled wooden still-rum from El Dorado: it’s sweet, feels the slightest bit sticky, and has strong notes of dark fruits, red licorice, plums, raisins and an almond chocolate bar gone soft in the heat. There’s other stuff in there as well – some caramel, vanilla, pepper again, light orange peel, but overall the whole thing is not particularly complex, and it ambles easily towards a short and gentle finish of no particular distinction that pretty much displays some dark fruit, caramel, anise and molasses, and that’s about it.

This process provides a tasting profile that reminds me of nothing so much than a slightly addled wooden still-rum from El Dorado: it’s sweet, feels the slightest bit sticky, and has strong notes of dark fruits, red licorice, plums, raisins and an almond chocolate bar gone soft in the heat. There’s other stuff in there as well – some caramel, vanilla, pepper again, light orange peel, but overall the whole thing is not particularly complex, and it ambles easily towards a short and gentle finish of no particular distinction that pretty much displays some dark fruit, caramel, anise and molasses, and that’s about it. So, until we know more, focus on the rum itself. It’s quiet and gentle and some cask strength lovers might say – not without justification – that it’s insipid. It has some good tastes, simple but okay, and hews to a profile with which we’re not entirely unfamiliar. It has a few off notes and a peculiar substrate of something different, which is a good thing. So in the end,

So, until we know more, focus on the rum itself. It’s quiet and gentle and some cask strength lovers might say – not without justification – that it’s insipid. It has some good tastes, simple but okay, and hews to a profile with which we’re not entirely unfamiliar. It has a few off notes and a peculiar substrate of something different, which is a good thing. So in the end,

By the time this rum was released in 2014, things were already slowing down for Velier in its ability to select original, unusual and amazing rums from DDLs warehouses, and of course it’s common knowledge now that 2014 was in fact the last year they did so. The previous chairman, Yesu Persaud, had retired that year and the arrangement with Velier was discontinued as DDL’s new Rare Collection was issued (in early 2016) to supplant them.

By the time this rum was released in 2014, things were already slowing down for Velier in its ability to select original, unusual and amazing rums from DDLs warehouses, and of course it’s common knowledge now that 2014 was in fact the last year they did so. The previous chairman, Yesu Persaud, had retired that year and the arrangement with Velier was discontinued as DDL’s new Rare Collection was issued (in early 2016) to supplant them. The nose had been so stuffed with stuff (so to speak) that the palate had a hard time keeping up. The strength was excellent for what it was, powerful without sharpness, firm without bite. But the whole presented as somewhat more bitter than expected, with the taste of oak chips, of cinchona bark, or the antimalarial pills I had dosed on for my working years in the bush. Thankfully this receded, and gave ground to cumin, coffee, dark chocolate, coca cola, bags of licorice (of course), prunes and burnt sugar (and I

The nose had been so stuffed with stuff (so to speak) that the palate had a hard time keeping up. The strength was excellent for what it was, powerful without sharpness, firm without bite. But the whole presented as somewhat more bitter than expected, with the taste of oak chips, of cinchona bark, or the antimalarial pills I had dosed on for my working years in the bush. Thankfully this receded, and gave ground to cumin, coffee, dark chocolate, coca cola, bags of licorice (of course), prunes and burnt sugar (and I

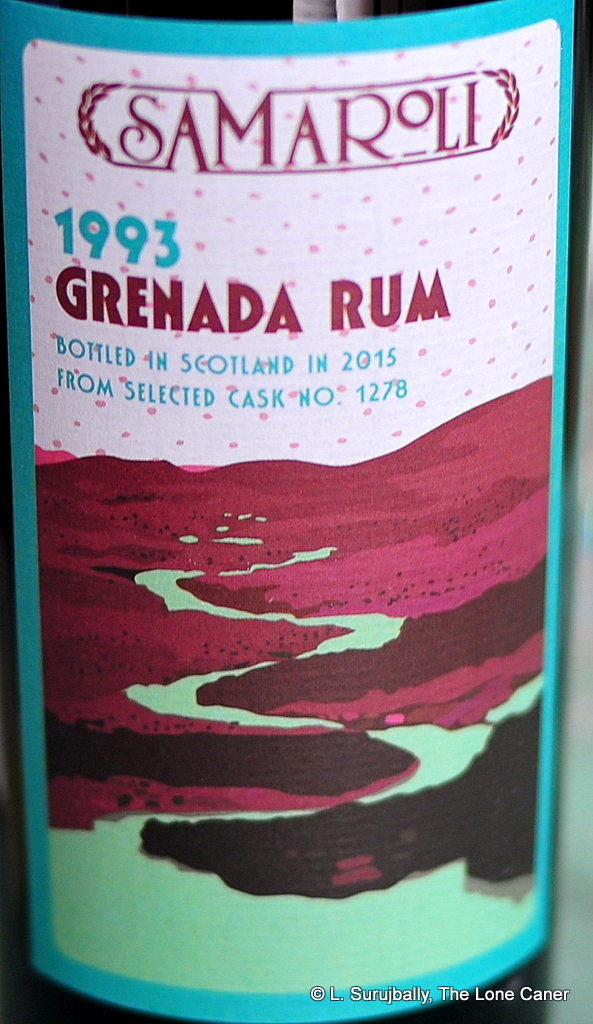

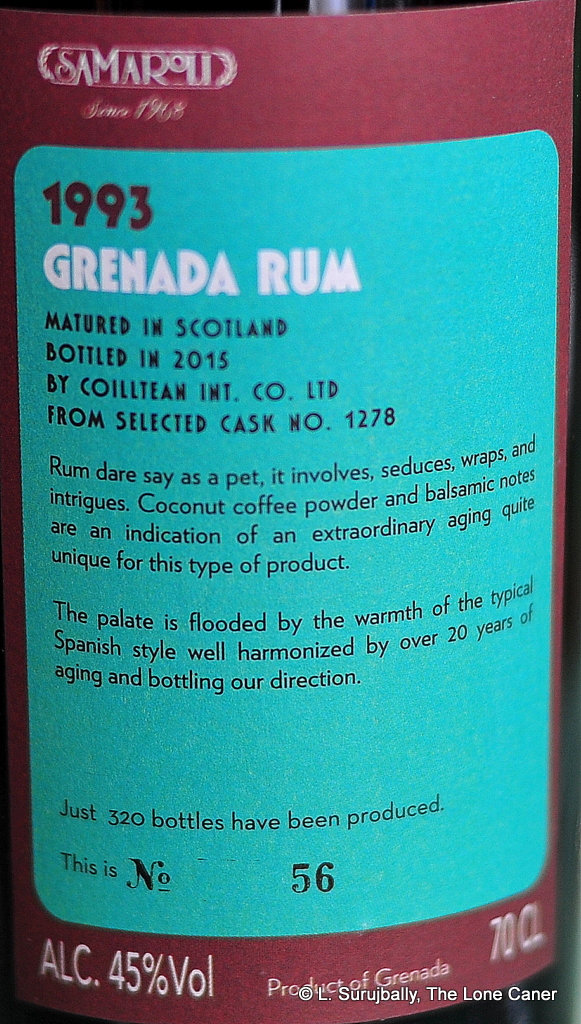

One such is this Samaroli rum sporting an impressive 22 years of continental ageing, hailing from Grenada – alas, not Rivers Antoine, but you can’t have everything (the rum very likely came from Westerhall – they ceased distilling in 1996 but were the only ones exporting bulk rum before that). You’ll look long and hard before you find any kind of write up about it, or anyone who owns it – not surprising when you consider the €340 price tag it fetches in stores and at auction. This is the second Grenada rum selected under the management of Antonio Bleve who took over operations at Samaroli in the mid 2000s and earned himself a similar reputation as Sylvio Samaroli (RIP), that of having the knack of picking right.

One such is this Samaroli rum sporting an impressive 22 years of continental ageing, hailing from Grenada – alas, not Rivers Antoine, but you can’t have everything (the rum very likely came from Westerhall – they ceased distilling in 1996 but were the only ones exporting bulk rum before that). You’ll look long and hard before you find any kind of write up about it, or anyone who owns it – not surprising when you consider the €340 price tag it fetches in stores and at auction. This is the second Grenada rum selected under the management of Antonio Bleve who took over operations at Samaroli in the mid 2000s and earned himself a similar reputation as Sylvio Samaroli (RIP), that of having the knack of picking right.  So what to make of this expensive two-decades-old Grenada rum released by an old and proud Italian house? Overall it’s really quite pleasant, avoids disaster and is tasty enough, just nothing special. I was expecting more. You’d be hard pressed to identify its provenance if tried blind. Like an SUV taking the highway, it stays firmly on the road without going anywhere rocky or offroad, perhaps fearing to nick the paint or muddy the tyres.

So what to make of this expensive two-decades-old Grenada rum released by an old and proud Italian house? Overall it’s really quite pleasant, avoids disaster and is tasty enough, just nothing special. I was expecting more. You’d be hard pressed to identify its provenance if tried blind. Like an SUV taking the highway, it stays firmly on the road without going anywhere rocky or offroad, perhaps fearing to nick the paint or muddy the tyres.

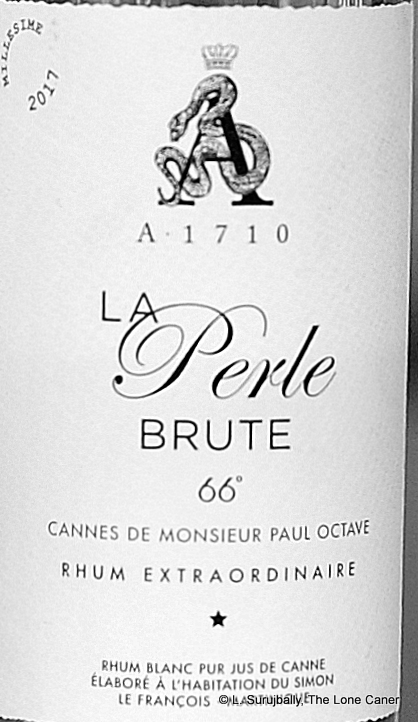

All that comes together in a rhum of uncommonly original aroma and taste. It opens with smells that confirm its provenance as an agricole, and it displays most of the hallmarks of a rhum from the blanc side (herbs, grassiness, crisp citrus and tart fruits)…but that out of the way, evidently feels it is perfectly within its rights to take a screeching ninety degree left turn into the woods. Woody and even meaty notes creep out, which seem completely out of place, yet somehow work. This all combines with salt, rancio, brine, and olives to mix it up some more, but the overall effect is not unpleasant – rather it provides a symphony of undulating aromas that move in and out, no single one ever dominating for long before being elbowed out of the way by another.

All that comes together in a rhum of uncommonly original aroma and taste. It opens with smells that confirm its provenance as an agricole, and it displays most of the hallmarks of a rhum from the blanc side (herbs, grassiness, crisp citrus and tart fruits)…but that out of the way, evidently feels it is perfectly within its rights to take a screeching ninety degree left turn into the woods. Woody and even meaty notes creep out, which seem completely out of place, yet somehow work. This all combines with salt, rancio, brine, and olives to mix it up some more, but the overall effect is not unpleasant – rather it provides a symphony of undulating aromas that move in and out, no single one ever dominating for long before being elbowed out of the way by another.

So let’s try it and see what the fuss is all about. Nose first. Well, it’s powerul sharp, let me tell you (63.8% ABV!), both crisper and more precise than the

So let’s try it and see what the fuss is all about. Nose first. Well, it’s powerul sharp, let me tell you (63.8% ABV!), both crisper and more precise than the

I was really and pleasantly surprised by how well it presented, to be honest. For a standard strength rhum, I expected less, but its complexity and changing character eventually won me over. Looking at others’ reviews of rhums in Reimonenq’s range I see similar flip flops of opinion running through them all. Some like one or two, some like that one more than that other one, there are those that are too dry, too sweet, too fruity (with a huge swing of opinion), and the little literature available is a mess of ups and downs.

I was really and pleasantly surprised by how well it presented, to be honest. For a standard strength rhum, I expected less, but its complexity and changing character eventually won me over. Looking at others’ reviews of rhums in Reimonenq’s range I see similar flip flops of opinion running through them all. Some like one or two, some like that one more than that other one, there are those that are too dry, too sweet, too fruity (with a huge swing of opinion), and the little literature available is a mess of ups and downs.

Rum Nation’s own

Rum Nation’s own

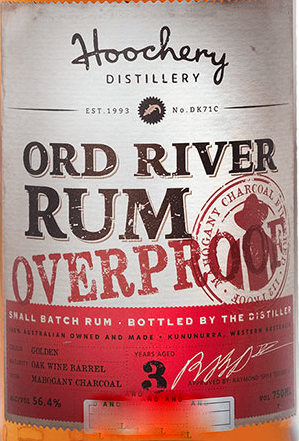

The results of all that micro-management are amazing.The nose, fierce and hot, lunges out of the bottle right away, hardly needs resting, and is immediately redolent of brine, olives, sugar water,and wax, combined with lemony botes (love those), the dustiness of cereal and the odd note of sweet green peas smothered in sour cream (go figure). Secondary aromas of fresh cane sap, grass and sweet sugar water mixed with light fruits (pears, guavas, watermelons) soothe the abused nose once it settles down.

The results of all that micro-management are amazing.The nose, fierce and hot, lunges out of the bottle right away, hardly needs resting, and is immediately redolent of brine, olives, sugar water,and wax, combined with lemony botes (love those), the dustiness of cereal and the odd note of sweet green peas smothered in sour cream (go figure). Secondary aromas of fresh cane sap, grass and sweet sugar water mixed with light fruits (pears, guavas, watermelons) soothe the abused nose once it settles down.