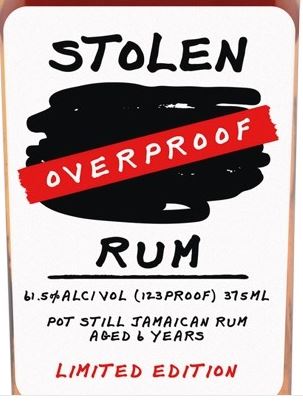

For all the faux-evasions about “a historic 250 year old Jamaican distillery” and the hints on the website, let’s not dick around – the Stolen Overproof is a Hampden Estate rum. You can disregard all the marketing adjectives and descriptors like “undiscovered”, “handmade” etc etc and just focus on what it is: a New Jamaican pot still rum, released at a tonsil-chewing 61.5%, aged six years and remarkably underpriced for what it is.

The Stolen Overproof has gotten favourable press from across the board almost without exception since its launch, even if there are few formal (i.e., review-website based) ones from the US itself — perhaps that’s because there’s no-one left writing essay-style rum reviews there these days except Paul Senft, and shorter ones from various Redditors (here, here, here and here). In my opinion, this is a rum that takes its place in the mid-range area right next to Rum Bar, Rum Fire, Smith & Cross and Dr. Bird — and snaps at the heels of Habitation Velier’s 2010 HLCF, of which this is not a cousin, but an actual brother.

If you doubt me, permit me to offer you a glass of this stuff, as my old-schoolfriend and sometime rum-chum Cecil R. did when he passed me a sample and insisted I try it. You’d think that Stolen Spirits, a company founded in 2010 which has released some underwhelming underpoofs and “smoked” rums was hardly one to warrant serious consideration, but this rum changed my mind in a hurry, and it’ll likely surprise you as well.

The nose was pure Jamaica, pure funk. It was dusty, briny, glue-y and wine-y, sharp and sweet and acidic. and redolent of a massive parade of fruits that came stomping through the nose with cheerful abandon. Peaches in syrup, near-ripe mangoes, guavas, pineapple, all dusted with a little salt and black pepper. It held not only these sharpish tart fruits but raisins, flambeed bananas, red currants, and as it opened further is also provided the lighter crispness of fanta, bubble-gum and flowers.

The nose was pure Jamaica, pure funk. It was dusty, briny, glue-y and wine-y, sharp and sweet and acidic. and redolent of a massive parade of fruits that came stomping through the nose with cheerful abandon. Peaches in syrup, near-ripe mangoes, guavas, pineapple, all dusted with a little salt and black pepper. It held not only these sharpish tart fruits but raisins, flambeed bananas, red currants, and as it opened further is also provided the lighter crispness of fanta, bubble-gum and flowers.

The rum is dark gold in the glass, 61.5% of high-test hooch and a Hampden, so a fierce palate is almost a given. Nor did it disappoint: it was sharp, with gasoline (!!), glue, acetones and olive oil charging right out of the gate. It tasted of fuel oil, coconut shavings, wet ashes, salt and pepper, slight molasses, tobacco and pancakes drenched in sweet syrup, cashew nuts…and bags and bags of fruit and other flavours, marching in stately order, one by one, past your senses – green apples, grapes, cloves, red currants, strawberries, ripe pineapples, soursop, lemon zest, burnt sugar cane, salt caramel and toffee. Damn – that was quite a handful. Even the finish – long and heated – added something: licorice, bubble gum, apples, pineapple and damp, fresh sawdust.

So, whew, deep breath. That’s quite a rum, representing the island in really fine style. I mean, the only way you’re getting closer to Jamaica without actually being there is to hug Christelle Harris in Brooklyn (which won’t get you drunk and might be a lot more fun, but also earn you a fight with everyone else around her who was thinking of doing the same thing). Essentially, it’s a Jamaican flavour bomb and the other remarkable thing about it is who made it, and from where.

The Stolen Overproof is an indie bottling — the company was formed in 2010 in New Zealand, and seems to be a primarily US based op these days — and the story I heard was that somehow they laid hands on some barrels of Hampden distillate way back in 2016 (Scott Ferguson mentions it was 5000 cases in his video review) and brought it to market. This is fairly recently, you might say, but even a mere three years ago, Hampden was not a household name, having just launched themselves into the global marketplace, and Velier’s 2010 6 YO HLCF only reached the greater rum audience in 2017 – apparently this rum is from the same batch of barrels. The Stolen is still relatively affordable if you can find it (US$18 for a 375ml bottle), and my only guess is that they literally did not know what they had and put a standard markup on the rum, never imagining how huge Jamaica rum of this kind would become in the years ahead.

When discussing Bacardi’s near-forgotten foray into limited bottlings, I remarked that just because you slap a Jamaican distillery name on a label does not mean you instantly have a great juice. But the reverse can also be true: you can have an almost-unobserved release of an unidentified Jamaican rum from a near-unknown third-tier bottler, and done right and done well, it’ll do its best to wow your socks off. This is one of those.

(#669)(85/100)

Other Notes

60,000 1/2 sized 375ml bottles were issued, so ~22,500 liters. All ageing was confirmed to be at Hampden Estate.

Opinion, somewhat tangential to the review….

If you want to know why I generally disregard the scorings and opinions on Rum Ratings, searching for this rum tells you why. This is a really good piece of work that’s been on the market for three years, and on that site and in all that time, it has garnered a rich and varied total of six scores – one 9-pointer, three at 7 points, one of 4 … and Joola69’s rating of 1. “Just another Jamaican glue and funk rum” he sneered rather contemptuously from the commanding heights of his 2,350 other rum ratings (the top choices of which are mostly devoted to Spanish/Latin column still spirits). If you want a contrary opinion that indicts the New Jamaicans as a class, there’s one for you.

Certainly such rums as the gentleman champions have their place and they remain great sellers and crowd pleasing favourites. But really good rums should — and do — adhere to rather higher standards than just pleasing everyone with soft sweet smoothness, and in this case, a dismissive remark like the one made simply shows the author does not know what good rums have developed into, and, sadly, that having scored more than 2000 rums hasn’t improved or changed his outlook. Which is bad for all those who blindly follow and therefore never try a rum like these New Jamaicans, but good for the rest of us who can now get more of the good stuff for ourselves. Perhaps I should be more grateful.

Rumaniacs Review #083 | 0544

Rumaniacs Review #083 | 0544 Opinion

Opinion

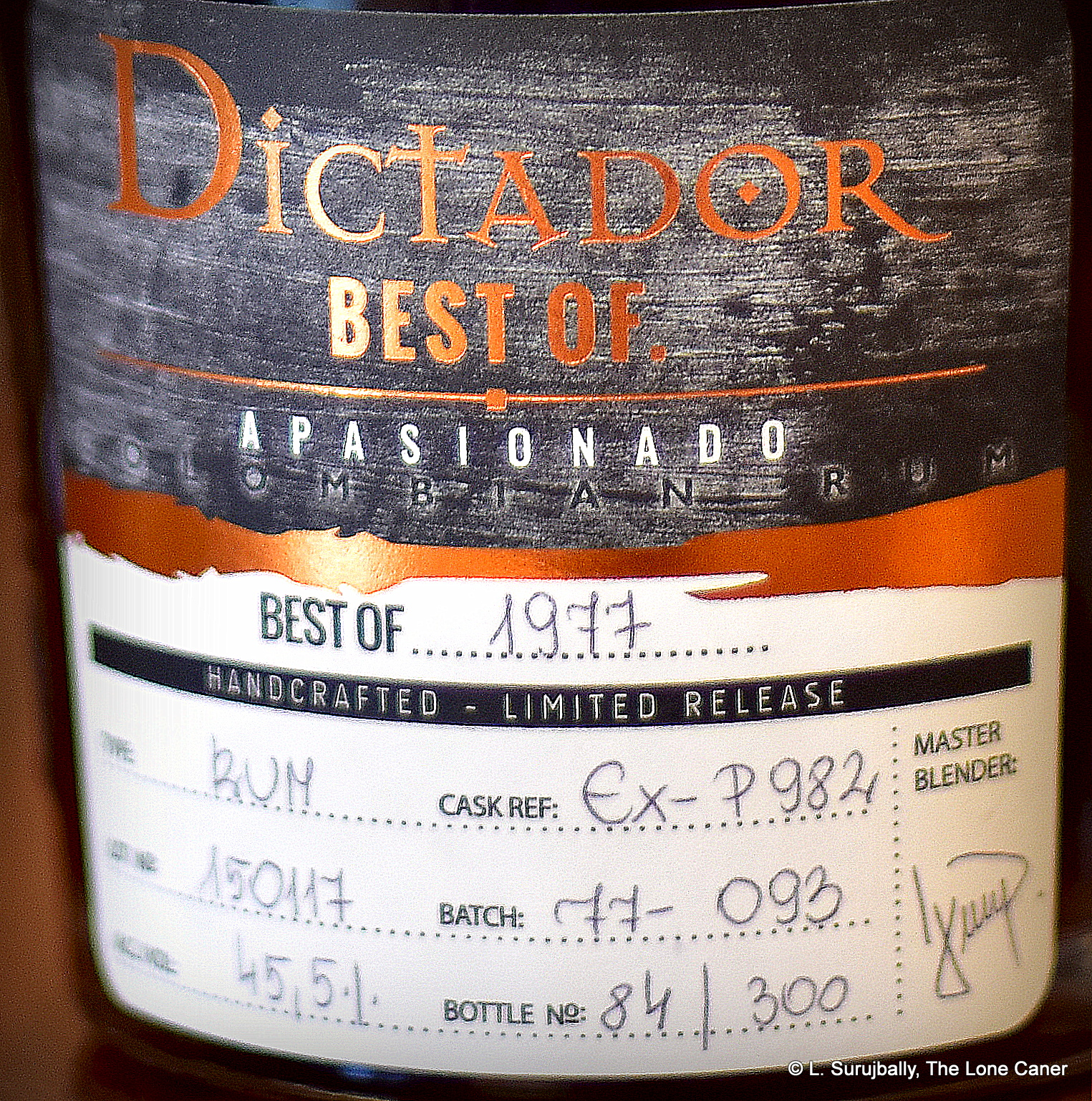

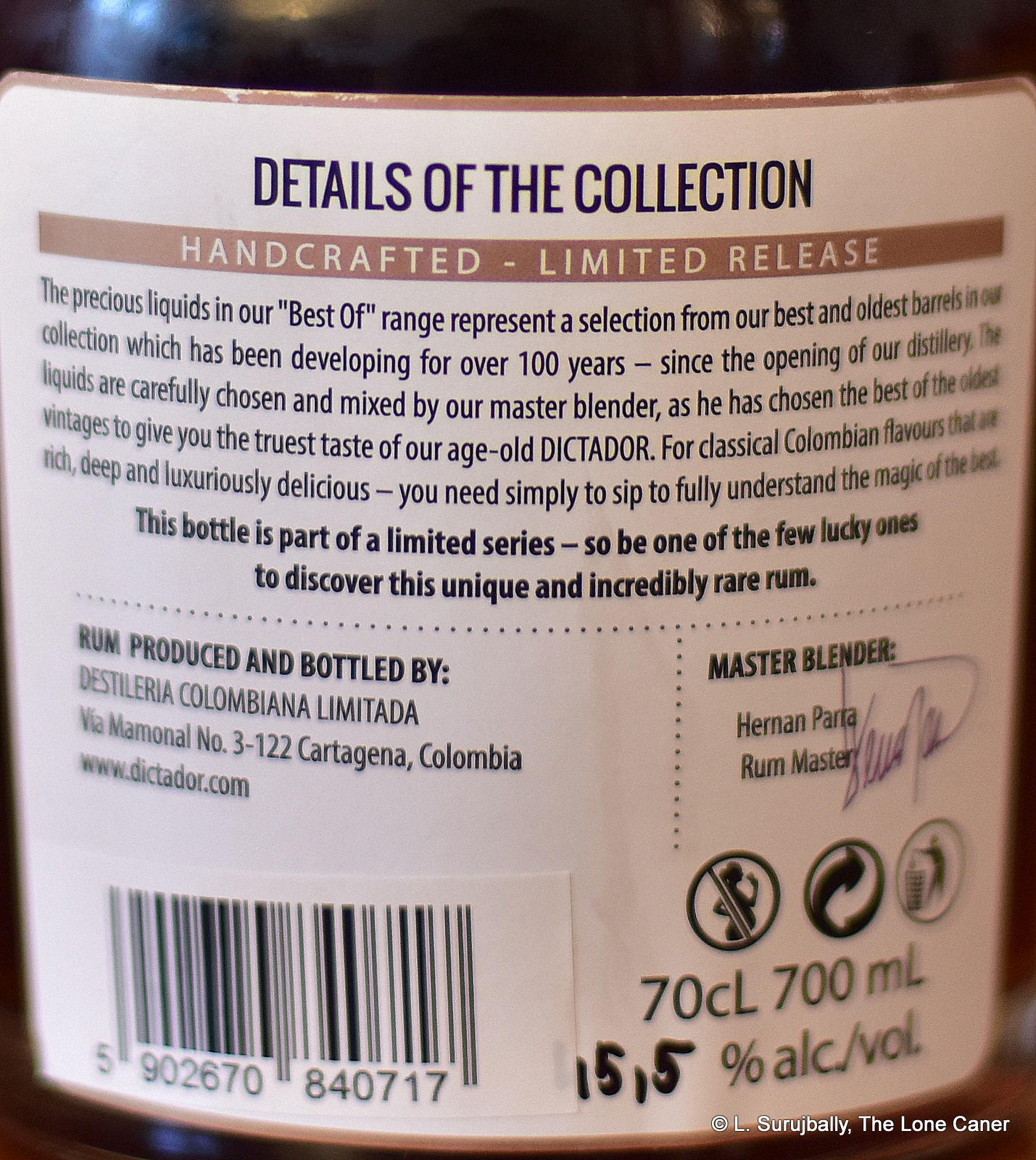

Anyway, tasting notes: all those who have tried the various Dictador expressions have remarked on the coffee undertones: that remained strong here as well – it’s something of a Dictador signature. It was soft and rounded, exhibiting gentle, creamy notes of sweet blancmange, bon bons and caramel. There was something of a red wine background here, raisins, and a vague fruitiness that was maddeningly elusive because it never quite emerged and came to the fore with any kind of authority. The nose therefore came through as something of a sleeping beauty behind a frosted glass case – I could sense some potential, but was never quite able to get the kiss of life from it…the liqueur note to the smells, while not as overpowering as on the 20, kept getting in the way.

Anyway, tasting notes: all those who have tried the various Dictador expressions have remarked on the coffee undertones: that remained strong here as well – it’s something of a Dictador signature. It was soft and rounded, exhibiting gentle, creamy notes of sweet blancmange, bon bons and caramel. There was something of a red wine background here, raisins, and a vague fruitiness that was maddeningly elusive because it never quite emerged and came to the fore with any kind of authority. The nose therefore came through as something of a sleeping beauty behind a frosted glass case – I could sense some potential, but was never quite able to get the kiss of life from it…the liqueur note to the smells, while not as overpowering as on the 20, kept getting in the way. Now that’s not to say we’re sure, when all is said and done, the nose nosed, the palate palated and the finish finished, that we’re entirely clear what we had. Certainly it was some of something, but was it much of anything? I’m going to have to piss off some people (including maybe even my compadre in the Philippines) by suggesting that yes, I think it was…better, at least, than the preceding remarks might imply, or than I had expected going in. For one thing, while it was sweet, it was not excessively so (at least compared to the real dentist’s wet dreams such as

Now that’s not to say we’re sure, when all is said and done, the nose nosed, the palate palated and the finish finished, that we’re entirely clear what we had. Certainly it was some of something, but was it much of anything? I’m going to have to piss off some people (including maybe even my compadre in the Philippines) by suggesting that yes, I think it was…better, at least, than the preceding remarks might imply, or than I had expected going in. For one thing, while it was sweet, it was not excessively so (at least compared to the real dentist’s wet dreams such as