Foursquare’s Exceptional Cask Series gets the lion’s share of the attention showered on the distillery these days, and the Doorly’s “standard line” gets most of the remainder, yet many deep diving aficionados reserve the real gold for the Foursquare-Velier collaborations. And while some wags humorously remark that the series’ are only excuses for polysyllabic rodomontade, the truth is that the collaborations are really good, just not as visible: they are released less often and with a more limited outturn than the big guns people froth over on social media. So not unnaturally they attract attention mostly at bidding time on online auctions, where they reliably climb in price as the years turn and the stock diminishes.

There currently eight rums in the set, which have been issued since February 2016 (when the famed 2006 10 YO came out): they are, in order of release as of January 2023, the 2016, Triptych, Principia, Destino (whether there’s only one, or two, is examined below), Patrimonio, Plenipotenziario, Sassafras and Racounteur. All are to one extent or another limited bottlings — and while they do not form an avenue to explore more experimental releases (like the pot still or LFT Foursquares in the HV series, for example), they are, in their own way, deemed special.

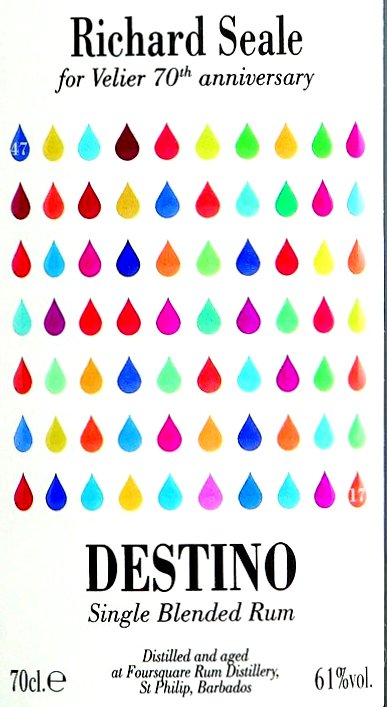

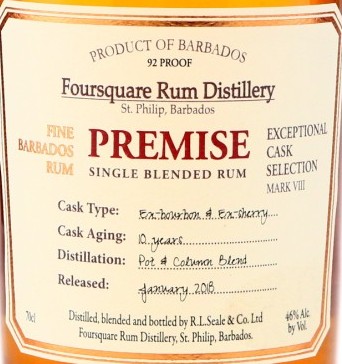

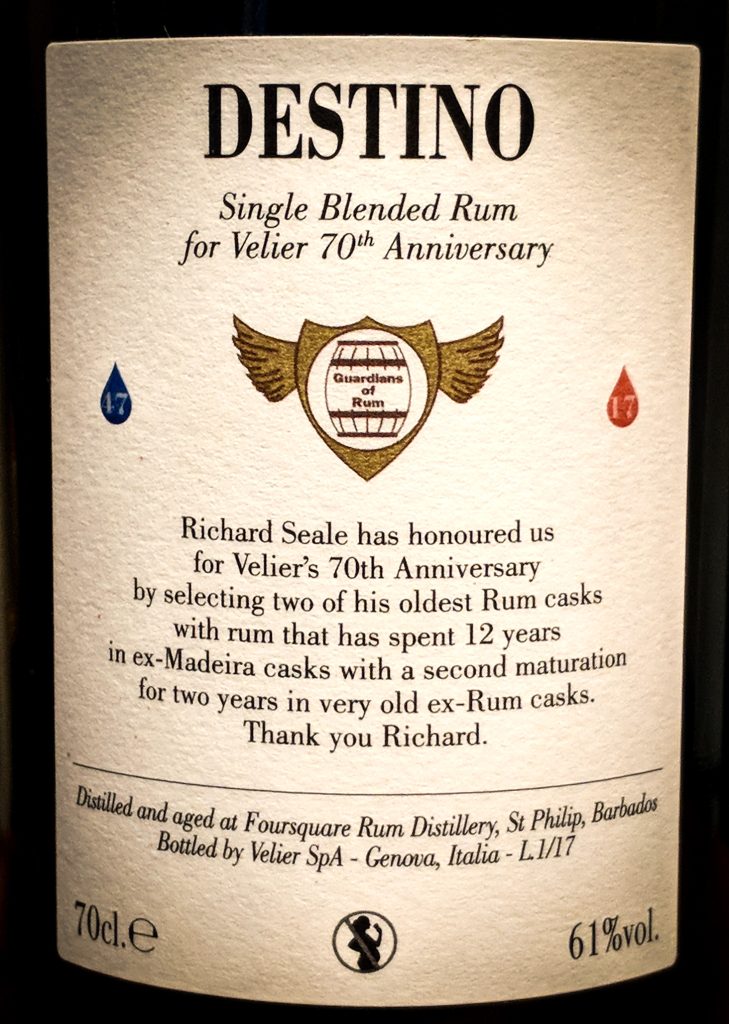

On the face of it, the Destino really does not appear to be anything out of the ordinary – which is to say, it conforms to the (high) standards Foursquare has set which have now almost become something of their signature. The rum is a pot-column blend, distilled in 2003 and released in December of 2017: between those dates it was aged 12 years in ex-Madeira casks and a further two in ex-Bourbon, and 2,610 of the “standard” general release edition were pushed out the door at a robust 61%, preceded by 600 bottles of the Velier 70th Anniversary edition at the same strength.

What we get was a very strong, very rich and very fruity-winey nose right off the bat. It smells of sweet apple cider, strawberries, gherkins, fermenting plums and prunes, but also sweeter notes of apricots, peaches are noticeable, presenting us with a real fruit salad. A little vanilla and some cream can be sensed, a sort of savoury pastry, but with molasses, caramel, butterscotch all AWOL. Something of a crisply cold fine wine here, joined at the last by charred wood, cloves, soursop, and a vague lemony background.

What we get was a very strong, very rich and very fruity-winey nose right off the bat. It smells of sweet apple cider, strawberries, gherkins, fermenting plums and prunes, but also sweeter notes of apricots, peaches are noticeable, presenting us with a real fruit salad. A little vanilla and some cream can be sensed, a sort of savoury pastry, but with molasses, caramel, butterscotch all AWOL. Something of a crisply cold fine wine here, joined at the last by charred wood, cloves, soursop, and a vague lemony background.

The citrus takes on a more forward presence when the rum is tasted, with the initial palate possessing all the tart creaminess of a key lime pie, while not forgetting a certain crisp pastry note as well. It’s delicious, really, and hardly seems as strong as it is. Stewed apples, green grapes, white guavas take their turn as the rum opens up: it turns into quite a mashup here, yet it’s all as distinct as adjacent white keys on a piano. With water emerge additional flavours: some freshly baked sourdough bread, vanilla, dates, figs, with sage, cloves, white pepper and cinnamon rounding things out delectably.

The finish is perfectly satisfactory: it’s nice and long and aromatic, yet introduces nothing new: it serves as more of a concluding summation, like the final needed paragraph to one of Proust’s long-winded essays. The rum doesn’t leave you exhausted in quite the same way as that eminent French essayist does, but you are a bit wrung out with its complexities and power when you’re done, though. And the way it winds to a conclusion is like a long exhaled breath of all the good things it encapsulates.

So…with all of the above out of the way, is it special? Several of the ECS releases are of similar provenance and have been rated by myself and others at similar levels of liking, so is there actually a big deal to be made here, and is there a reason for the Destino to be regarded as something more “serious”?

Not really, but that’s because the rum is excellent, and works, on all levels. It noses fine, tastes fine, finishes with a snap and there’s complexity and strength and texture and quality to spare. It does Foursquare no dishonour at all, and burnishes the reputation the house nicely (as if that were needed). The rum, then, is special because we say it is: viewed objectively, it’s simply on a level with the high bar set by the company and is neither a slouch nor a disappointment, “just” a very good rum.

Sometimes I think Richard may have painted himself into a corner with these rums he puts out: they are all of such a calibre that to maintain a rep for high quality means constantly increasing the quality lest the jaded audience get bored. There is a limit to how far that can be done, but let’s hope he hasn’t reached it yet — because know I want more of these.

(#944)(86/100) ⭐⭐⭐⭐

Other Notes

- There is a “47” and a “17” on the “Teardrops” box’s top left and bottom right tears. They reference the founding of Velier in 1947; and the issuance of the rum and 70th Anniversary of the Company, in 2017. There are total of seventy tears, of course. The numbers are repeated on the back label

- Wharren Kong the Singaporean artist, designed the Teardrops graphic.

- The pair was tried side by side three times: once in 2018, again in December 2021 in Berlin (from samples) and again at the 2022 Paris WhiskyLive (from bottles).

Are the two expressions of the Destino — the general release “standard” and the Velier 70th Anniversary Richard Seale “Teardrop” edition — different or the same? The question is not a mere academic exercise in anal-retentive pedantry of interest only to rum geeks: serious money is on the line for the “Seale” release. The short answer is no, and the long answers is yes. Sorry.

What happened is that as the Destino barrels were being prepped in 2017, Luca called Richard — some months before formal release — and asked for an “old rum” for the 70th Anniversary collection. Richard, who doesn’t do specials, anniversaries or cliches, initially refused, but after Luca practically broke down in tears (I exaggerate a little for effect), Richard raised his fists to heaven in a “why me?” gesture (I exaggerate a little more), grumbled a bit longer, and then reluctantly suggested that maybe, perhaps, possibly, just this once, it could be arranged to have six hundred bottles of the Destino relabelled and reboxed with the Velier 70th Anniversary colours. This was initially estimated as two casks of the many that were being readied for final blending. Luca agreed because the deadline for his release was tight, and so it was done. The label on the “Teardrops” was prepared on that basis, way in advance of either release.

Except that for one thing, it ended up being three casks, not two, and for another, “Teardrops” was in fact decanted, bottled and released a couple of months earlier than “Standard.” Yet they both came from the same batch of rum laid down in 2003, and aged identically for the same years in ex-bourbon and ex-Madeira … in that sense they are the same. The way they diverge is that three barrels were separated out and aged a couple of months less than the general release. So, according to Richard, who took some time out to patiently explain this to me, “In theory they are ‘different’- like two single casks – but in reality it’s the same batch of rum with the same maturation.”

Observe the ramifications of that almost negligible separation and the special labelling: on Rum Auctioneer, any one of the 600 bottles of “Teardrops” sells for £2000 or more, while one of the 2,610 bottles of the standard goes for £500. People claim “Teardrops” is measurably better because (variously) the box is different, the taste is “recognizably better”, or because the labelling says “selected two of his oldest Rum casks” and “very old ex-Rum casks” and not ex-Madeira and ex-bourbon. Or, perhaps because they are seduced by the Name and the much more limited 600 bottles, and let their enthusiasm get the better of them.

Observe the ramifications of that almost negligible separation and the special labelling: on Rum Auctioneer, any one of the 600 bottles of “Teardrops” sells for £2000 or more, while one of the 2,610 bottles of the standard goes for £500. People claim “Teardrops” is measurably better because (variously) the box is different, the taste is “recognizably better”, or because the labelling says “selected two of his oldest Rum casks” and “very old ex-Rum casks” and not ex-Madeira and ex-bourbon. Or, perhaps because they are seduced by the Name and the much more limited 600 bottles, and let their enthusiasm get the better of them.

Yes the box is different and the labelling description is not the same: this is as a result of the timing of the box and labels’ printing way in advance of the actual release of the rum, and so some stuff was just guessed, or fluff-words were printed. We saw the same thing with Amrut catalogue-versus-label difference in 2022), but I reiterate: the liquid is all of a piece, and the rums within have the miniscule taste variation attendant on any two barrels, even if laid down the same day and aged the same way. Maybe one day I’ll do a separate review of Teardrops just because of that tiny variation, but for the moment, this one will stand in for both.