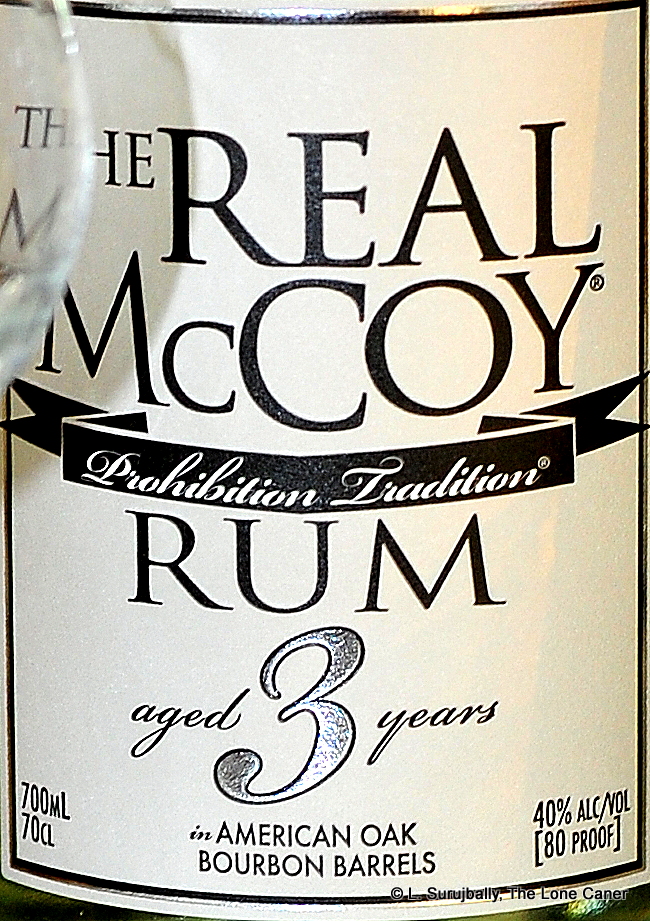

Last week, I remarked briefly on persons who are famous or excel in some aspect of their lives, who then go off an lend their names to another product, like spirits – Blackwell was one of these, George Clooney’s Casamigos tequila is another, Bailey Pryor’s Real McCoy line might be among the best known, and here is one that crossed my path not too long ago, a Hawaiian white rum made with the imprimatur of Van Halen’s Sammy Hagar who maintains a residence on Maui and has long been involved in restaurants and spirits (like Cabo Wabo tequila) as a sideline from the gigs for which he is more famous.

It’s always a toss-up whether the visibility and “fame” of such a rum is canny branding / marketing or something real, since the advertising around the associated Name usually swamps any intrinsic quality the spirit might have had to begin with. There’s a fair amount of under-the-hood background (or lack thereof) to the production of this rum, but for the moment, I want to quickly get to the tasting notes, just to get that out of the way.

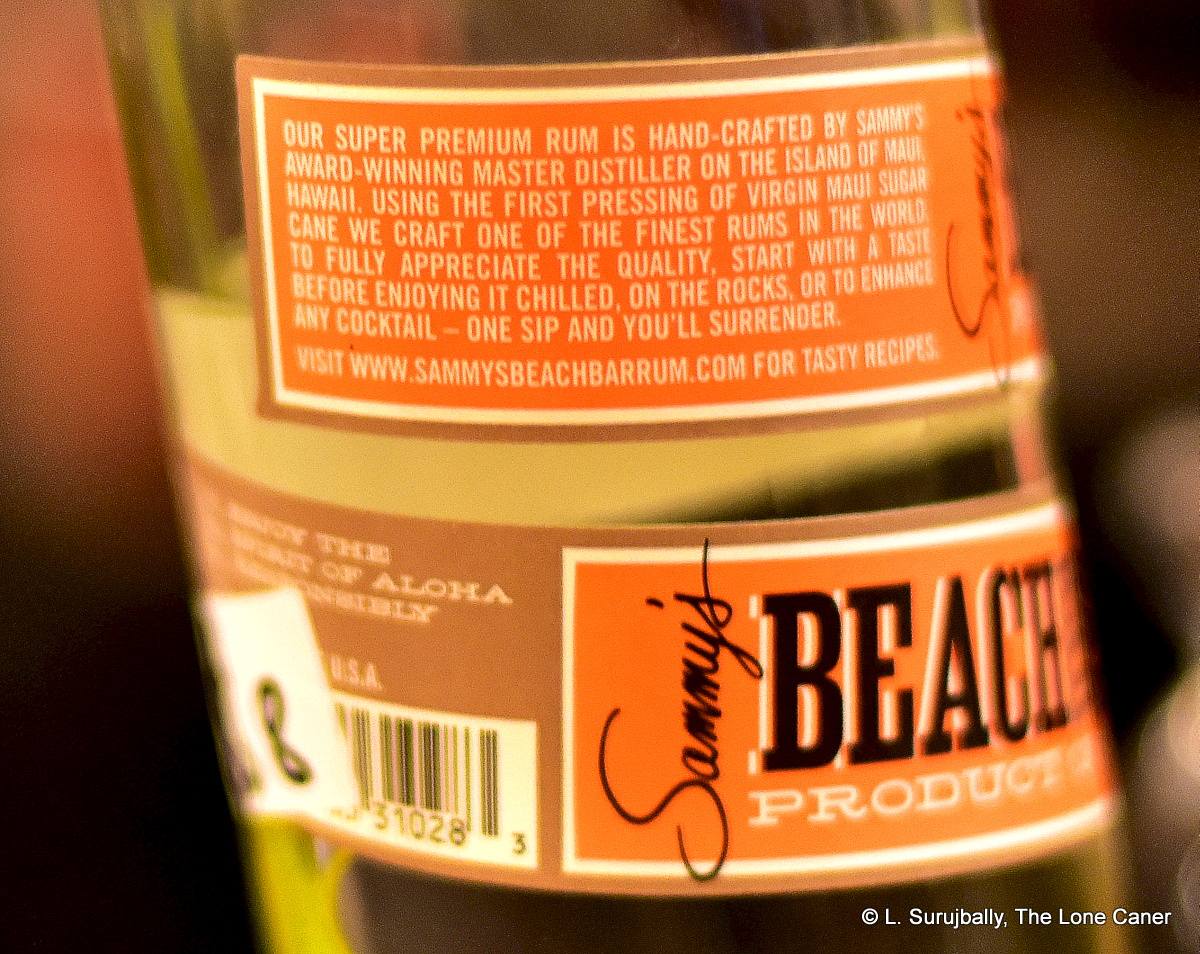

First off, it’s a 40% rum, white, and filtered, so the real question is what’s the source? The back label remarks that it’s made from “first pressing of virgin Maui sugar cane” (as opposed to the slutty non-Catholic kind of cane, I’m guessing) but the YouTube video (timestamp 1:02) that promotes it suggests brown sugar (which is true) so, I dunno. Whatever the case, it really does smell more like an agricole than a molasses-based rum: it starts, for example, with soda pop – sprite, fanta – adds bubble gum and lemon zest, and has a sort of vegetal grassy note that makes me think that the word “green” is not entirely out of place. Also iced tea with a mint leaf, and the tartness of ginnip and gooseberries. It’s also surprisingly sharp for something at standard strength, though not enough to be annoying.

First off, it’s a 40% rum, white, and filtered, so the real question is what’s the source? The back label remarks that it’s made from “first pressing of virgin Maui sugar cane” (as opposed to the slutty non-Catholic kind of cane, I’m guessing) but the YouTube video (timestamp 1:02) that promotes it suggests brown sugar (which is true) so, I dunno. Whatever the case, it really does smell more like an agricole than a molasses-based rum: it starts, for example, with soda pop – sprite, fanta – adds bubble gum and lemon zest, and has a sort of vegetal grassy note that makes me think that the word “green” is not entirely out of place. Also iced tea with a mint leaf, and the tartness of ginnip and gooseberries. It’s also surprisingly sharp for something at standard strength, though not enough to be annoying.

In that promotional video, Mr. Hagar says that the most distinct thing about the rum is the nose, and I believe it, because the palate pretty much fails by simply being too weak and insufficient to carry the promise of the nose on to the tongue in any meaningful way. It’s sharp and thin, quite clear, and tastes of lemon rind, pickled gherkins, freshly mown grass, sugar water, cane juice, and with the slightly off background of really good olive oil backing it up. But really, at end, there’s not much really there, no real complexity, and all of it goes away fast, leaving no serious aftertaste to mull over and savour and enjoy. The finish circles back to the beginning and the sense of sprite / 7-up, a bit of grass and a touch of light citrus, just not enough to provide a serious impression of any kind.

This is not really a rum to have by itself. It’s too meek and mild, and sort of presents like an agricole that isn’t, a dry Riesling or a low-rent cachaca minus the Brazilian woods, which makes one wonder how it got made to taste that way.

And therein lies something of an issue because nowhere are the production details clearly spelled out. Let’s start at the beginning: Mr. Hagar does not own a distillery. Instead, like Bailey Pryor, he contracts out the manufacture of the rum to another outfit, Hali’imaile Distilling, which was established in 2010 on Maui – the owners were involved in a less than stellar rum brand called Whaler’s which I personally disliked intensely. They in turn make a series of spirits – whiskey, vodka, gin, rum – under a brand called Pau, and what instantly makes me uneasy is that for all the bright and sparkling website videos and photos, the “History” page remarks that pineapple is used as a source material for their vodka, rum is not mentioned, and cane is nowhere noted as being utilized; note, though, that Mr. Hagar’s video mentions sugar cane and brown sugar without further elaboration, and the Hali’imaile Distilling Company did confirm they use a mash of turbinado sugar. However, in late 2016 Hali’imaile no longer makes the Sammy’s rum. In that year the sugar mill on Maui closed and production was shifted to Puerto Rico’s Seralles distillery, which also makes the Don Q brand – so pay close attention to your label, to see if you got a newer version of the rum, or the older Hawaiian one. Note that Levecke, the parent company of Hali’imaile, continues to be responsible for the bottling.

With some exceptions, American distillers and their rums seem to operate along such lines of “less is more” — the exceptions are usually where owners are directly involved in their production processes, ultimate products and the brands. The more supermarket-level rums give less information and expect more sales, based on slick websites, well-known promoters, unverifiable-but-wonderful origin stories and enthusiastic endorsements. Too often such rums (even ones labelled “Super Premium” like this one) when looked at in depth, show nothing but a hollow shell and a sadly lacking depth of quality. I can’t entirely say that about the Beach Bar Rum – it does have some nice and light notes, does not taste added-to and is not unpleasant in any major way – but the lack of information behind how it is made, and its low-key profile, makes me want to use it only for exactly what it is made: not neat, and not to share with my rum chums — just as a relatively unexceptional daiquiri ingredient.

With some exceptions, American distillers and their rums seem to operate along such lines of “less is more” — the exceptions are usually where owners are directly involved in their production processes, ultimate products and the brands. The more supermarket-level rums give less information and expect more sales, based on slick websites, well-known promoters, unverifiable-but-wonderful origin stories and enthusiastic endorsements. Too often such rums (even ones labelled “Super Premium” like this one) when looked at in depth, show nothing but a hollow shell and a sadly lacking depth of quality. I can’t entirely say that about the Beach Bar Rum – it does have some nice and light notes, does not taste added-to and is not unpleasant in any major way – but the lack of information behind how it is made, and its low-key profile, makes me want to use it only for exactly what it is made: not neat, and not to share with my rum chums — just as a relatively unexceptional daiquiri ingredient.

(#650)(72/100)

Other notes

- The rum is filtered but I am unable to say whether it has been aged. The video by Let’s Tiki speaks of an oak taste that I did not detect myself.