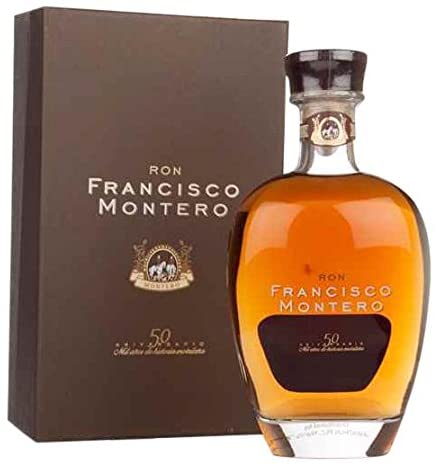

Francisco Montero is, unusually enough, a Spanish rum making concern, and the website has the standard founding myth of one man wanting to make rum and going after his dream and establishing a company in Granada to do so in 1963. Initially the company used sugar from cane (!!) grown around southern Spain to make their rums, but over time this supply dried up and now in the 21st century they source molasses from a number of different locations around the world, which they distill and age into various rums in their portfolio. Francisco Montero continues operations to this day, and in 2013 celebrated their 50th Anniversary with a supposedly special bottling to mark the occasion.

I say “supposedly” because after tasting, I must confess to wondering what exactly was so special about it. The nose itself started off well – mostly caramel, molasses, raisins, a dollop of vanilla ice cream, with hints of coffee and citrus, flowers and some delicate sweet, and some odd funkiness lurking in the background…shoes, rotting vegetables, some wood (it reminds me somewhat of the Dos Maderas 5+3).

But afterwards, things didn’t capitalize on that strong open or proceed with any kind of further originality. It tasted wispy and commercially anonymous, that was the problem, and gave over little beyond what was already in the nose. Molasses, caramel, some fruit – all that odd stuff vanished, and it became dry, unimpressive. Okay after ten minutes, it turned a tad creamy, and grudgingly gave up a green apple or two, toast, and some walnuts. But really? That was it? Big yawn. Finish was short, bland, faintly dry, a hint of dried fruits, caramel, brown sugar.

So what was this? Well, it’s a 40% ABV solera rum with differing accounts of whether the oldest component is five or ten years – but even if we’re generous and accept ten, there’s just not enough going on here to impress, to deserve the word “special” or even justify “anniversary”.

Reading around, you only get two different opinions – the cautiously positive ones from any of those that sell it, and the harshly negative from those who tried it. That’s practically unheard of for a premium ron that marks an event (50th anniversary, remember) and is of limited provenance (7000 bottles, not particularly rare, but somewhat “limited”, so ok). Most of the time people whinge about price and availability, but nobody really seems to care enough to make it a cause. Even the the ones who disliked it just spoke to taste, not cost. “Turpentine” growled one observer. “Quite disappointed,” wrote another, and the coup de grace was offered by a third “Who in their right mind has been buying this stuff for 50 years?!” Ouch.

I’m not that harsh, just indifferent — and while I accept that the rum was made specifically for palates sharing a preference for sherries, soleras and lighter ron profiles (e.g. locals, tourists and cruise ships, not the more exacting rumistas who hang around FB rum clubs), I still believe Montero could have done better. It’s too weak, too young, too expensive, and not interesting enough. If this is what the descendants of the great Spanish ron makers who birthed Bacardi and the “Spanish style” have come to when they want to make a special edition to showcase their craft, they should stop trying. The nose is all that makes me score this thing above 75, and for me, that’s almost like damning it with faint praise.

(#736)(76/100)

Other notes

- Master Quill, that sterling gent who was the source of the sample, scored it 78 and provided details of the production methodology.

- Not much else for the company has been reviewed except by the FRP, who reviewed the Gran Reserva back in 2017

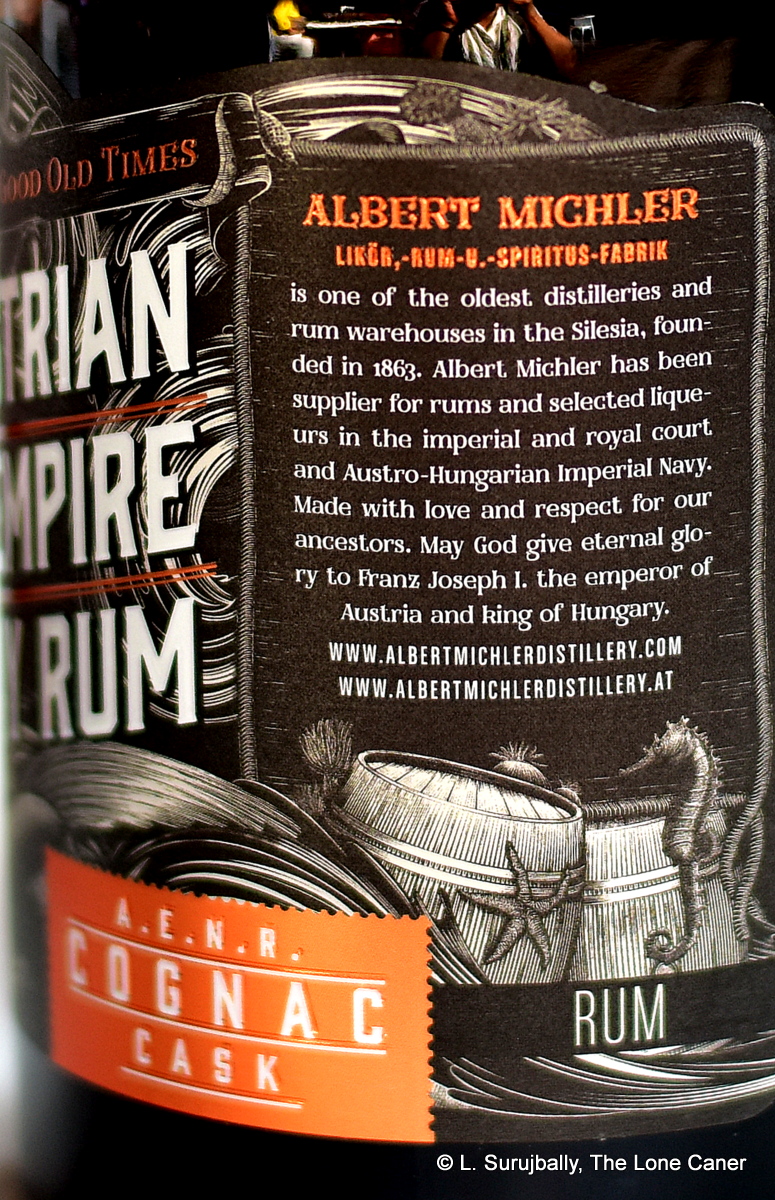

There are no records on whether the Austrian or Austro-Hungarian Navy ever used it or was supplied by the Michler distillery. Somehow I doubt it – it was far more likely it followed in the tradition of rum

There are no records on whether the Austrian or Austro-Hungarian Navy ever used it or was supplied by the Michler distillery. Somehow I doubt it – it was far more likely it followed in the tradition of rum

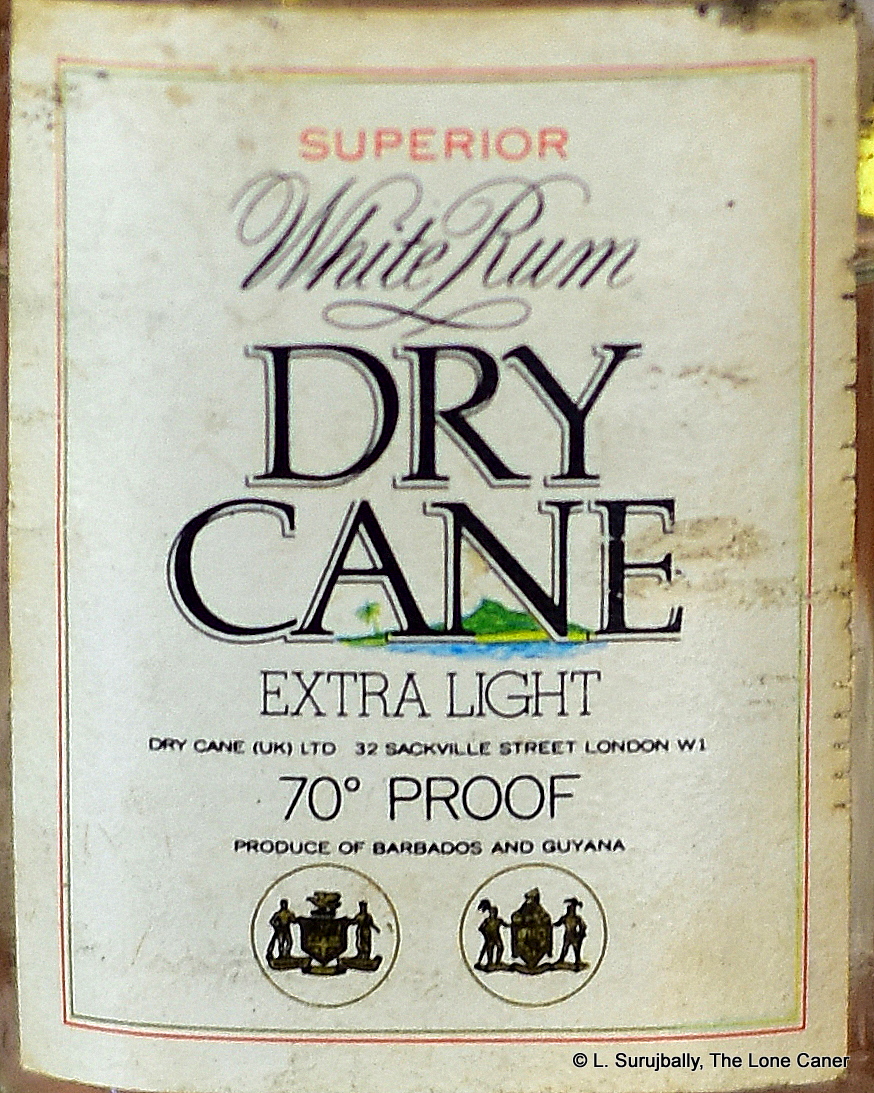

My inference is therefore that Dry Cane was a financing vehicle or shell company or wholly owned subsidiary set up for a short time to limit the exposure of the parent company (or Kinloch), as it dabbled in being an independent bottler — and just as quickly retreated, for no further products were ever made so far as I can tell. But since S&S also acquired a Gibraltar drinks franchise in 1968 and gained the concession to operate a duty free shop at Gibraltar airport in 1973, I suspect this was the rationale behind creating the rums in the first place, through the reason for its cessation is unknown. Certainly by the time S&S moved out of Sackville Street in the 1980s and to Gibraltar (where they remain to this day as part of a large conglomerate), the rum was no longer on sale.

My inference is therefore that Dry Cane was a financing vehicle or shell company or wholly owned subsidiary set up for a short time to limit the exposure of the parent company (or Kinloch), as it dabbled in being an independent bottler — and just as quickly retreated, for no further products were ever made so far as I can tell. But since S&S also acquired a Gibraltar drinks franchise in 1968 and gained the concession to operate a duty free shop at Gibraltar airport in 1973, I suspect this was the rationale behind creating the rums in the first place, through the reason for its cessation is unknown. Certainly by the time S&S moved out of Sackville Street in the 1980s and to Gibraltar (where they remain to this day as part of a large conglomerate), the rum was no longer on sale. Palate – Light and inoffensive, completely bland. Pears, sugar water, some mint. You can taste a smidgen of alcohol behind all that, it’s just that there’s nothing really serious backing it up or going on.

Palate – Light and inoffensive, completely bland. Pears, sugar water, some mint. You can taste a smidgen of alcohol behind all that, it’s just that there’s nothing really serious backing it up or going on.

Colour – Amber

Colour – Amber The Cor Cor “Green”, cousin to the

The Cor Cor “Green”, cousin to the

Given Japan has several rums which have made these pages (

Given Japan has several rums which have made these pages ( The Cor Cor Red was more generous on the palate than the nose, and as with many Japanese rums I’ve tried, it’s quite distinctive. The tastes were somewhat offbase when smelled, yet came together nicely when tasted. Most of what we might deem “traditional notes” — like nougat, or toffee, caramel, molasses, wine, dark fruits, that kind of thing — were absent; and while their (now closed) website rather honestly remarked back in 2017 that it was not for everyone, I would merely suggest that this real enjoyment is probably more for someone (a) interested in Asian rums (b) looking for something new and (c) who is cognizant of local cuisine and spirits profiles, which infuse the makers’ designs here. One of the reasons the rum tastes as it does, is because the master blender used to work for one of the awamori makers on Okinawa (it is a spirit akin to Shochu), and wanted to apply the methods of make to rum as well. No doubt some of the taste profile he preferred bled over into the final product as well.

The Cor Cor Red was more generous on the palate than the nose, and as with many Japanese rums I’ve tried, it’s quite distinctive. The tastes were somewhat offbase when smelled, yet came together nicely when tasted. Most of what we might deem “traditional notes” — like nougat, or toffee, caramel, molasses, wine, dark fruits, that kind of thing — were absent; and while their (now closed) website rather honestly remarked back in 2017 that it was not for everyone, I would merely suggest that this real enjoyment is probably more for someone (a) interested in Asian rums (b) looking for something new and (c) who is cognizant of local cuisine and spirits profiles, which infuse the makers’ designs here. One of the reasons the rum tastes as it does, is because the master blender used to work for one of the awamori makers on Okinawa (it is a spirit akin to Shochu), and wanted to apply the methods of make to rum as well. No doubt some of the taste profile he preferred bled over into the final product as well.

Colour – Light Gold

Colour – Light Gold

Here’s what we know – made from rendered sugar cane juice (“honey”), fermented for 72 hours using wild yeast, column distilled, then aged in all kinds of barrels – American oak (ex-bourbon), cognac, Pedro Ximenez and also Marcuya “fruit of passion” wood from Paraguay. Once that’s done, the resultant rons are blended to form the final product. The age is currently unknown — I’ll update this paragraph if I get feedback from their marketing folks — but I’ll hazard a guess it’s medium…about 3-6 years. Little of this, by the way, is noted on the label, which only says it is a Paraguayan rum, commemorates the 1869 battle, is aged in oak vats and 40%. Wonderful. Clearly the word “disclosure” gets more lip service than real purchase over there.

Here’s what we know – made from rendered sugar cane juice (“honey”), fermented for 72 hours using wild yeast, column distilled, then aged in all kinds of barrels – American oak (ex-bourbon), cognac, Pedro Ximenez and also Marcuya “fruit of passion” wood from Paraguay. Once that’s done, the resultant rons are blended to form the final product. The age is currently unknown — I’ll update this paragraph if I get feedback from their marketing folks — but I’ll hazard a guess it’s medium…about 3-6 years. Little of this, by the way, is noted on the label, which only says it is a Paraguayan rum, commemorates the 1869 battle, is aged in oak vats and 40%. Wonderful. Clearly the word “disclosure” gets more lip service than real purchase over there.

The strangely named Doctor Bird rum is another company’s response to

The strangely named Doctor Bird rum is another company’s response to

Light amber in colour and bottled at 43%, it certainly did not nose like your favoured Caribbean rum. It smelled initially of congealed honey and beeswax left to rest in an old unaired cupboard for six months – that same dusty, semi-sweet waxy and plastic odour was the most evident thing about it. Letting it rest produced additional aromas of brine, olives and ripe mangoes in a pepper sauce. Faint vanilla and caramel – was this perhaps made from jaggery, or added to after the fact? Salty cashew nuts, fruit loops cereal and that was most or less it – a fairly heavy, dusky scent, darkly sweet.

Light amber in colour and bottled at 43%, it certainly did not nose like your favoured Caribbean rum. It smelled initially of congealed honey and beeswax left to rest in an old unaired cupboard for six months – that same dusty, semi-sweet waxy and plastic odour was the most evident thing about it. Letting it rest produced additional aromas of brine, olives and ripe mangoes in a pepper sauce. Faint vanilla and caramel – was this perhaps made from jaggery, or added to after the fact? Salty cashew nuts, fruit loops cereal and that was most or less it – a fairly heavy, dusky scent, darkly sweet.

If we accept these data points, then of course the Casino is not, by all current definitions, a rum, and in point of fact, the entry might just as easily be listed in the Rumaniacs page since this version is no longer being made — the word “rum” was either replaced by “room” or dropped completely from the label when Hungary joined the EU in 2004, and that suggests a manufacture for the product I tasted of around 1988-2003 which actually makes it a heritage rum entry, but what the hell.

If we accept these data points, then of course the Casino is not, by all current definitions, a rum, and in point of fact, the entry might just as easily be listed in the Rumaniacs page since this version is no longer being made — the word “rum” was either replaced by “room” or dropped completely from the label when Hungary joined the EU in 2004, and that suggests a manufacture for the product I tasted of around 1988-2003 which actually makes it a heritage rum entry, but what the hell.

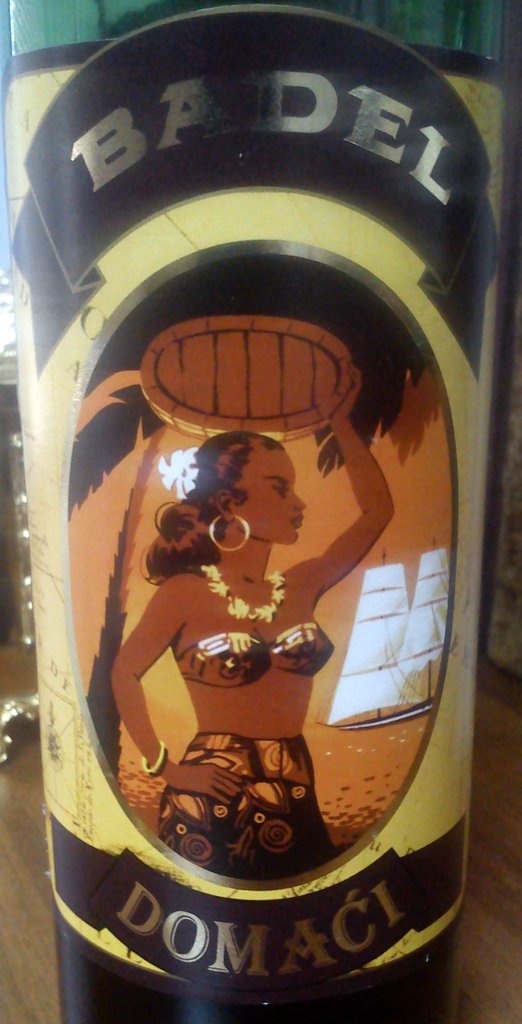

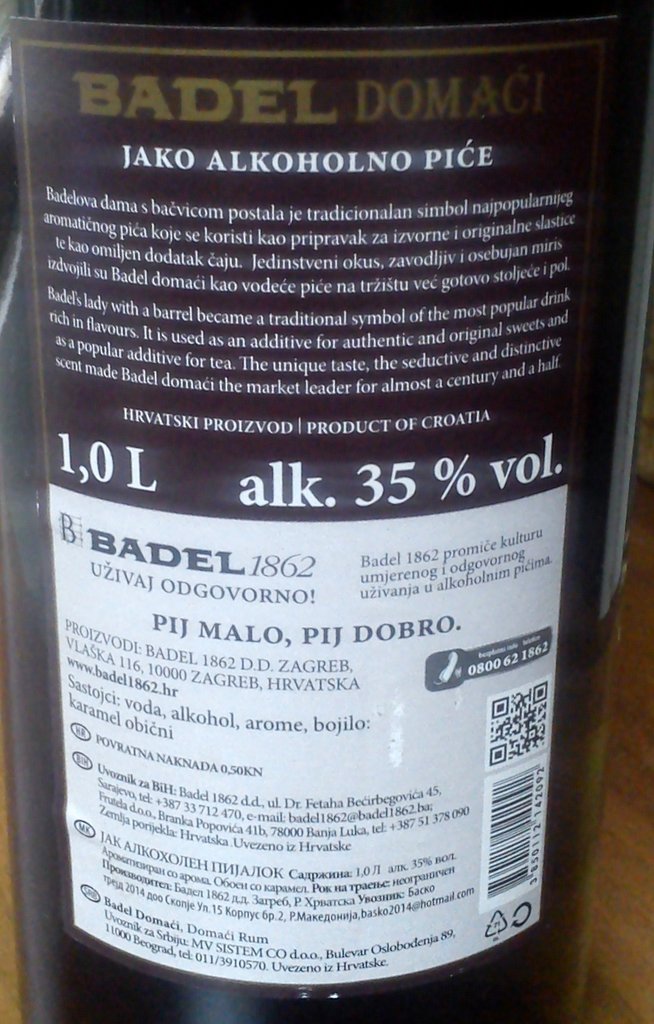

Unsurprisingly it’s mostly for sale in the Balkans — Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia, with outliers in Germany — and has made exactly zero impact on the greater rum drinking public in the West. Wes briefly touched on it with a review of

Unsurprisingly it’s mostly for sale in the Balkans — Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia, with outliers in Germany — and has made exactly zero impact on the greater rum drinking public in the West. Wes briefly touched on it with a review of

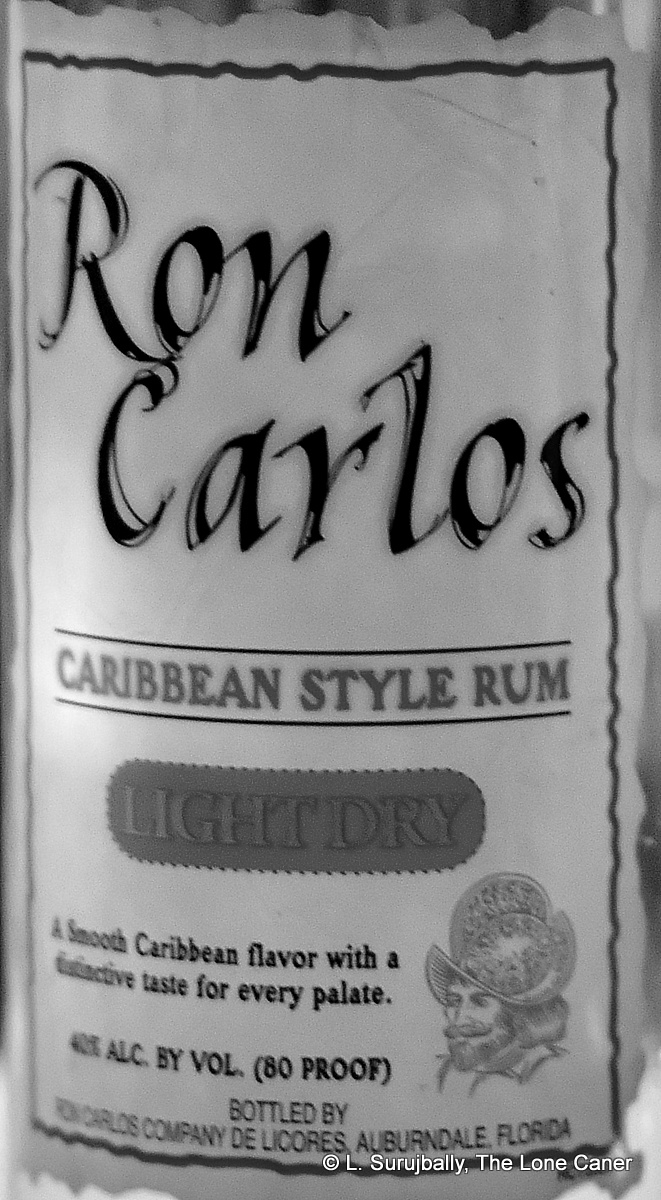

The rum was standard strength (40%), so it came as little surprise that the palate was very light, verging on airy – one burp and it was gone forever. Faintly sweet, smooth, warm, vaguely fruity, and again those minerally metallic notes could be sensed, reminding me of an empty tin can that once held peaches in syrup and had been left to dry. Further notes of vanilla, a single cherry and that was that, closing up shop with a finish that breathed once and died on the floor. No, really, that was it.

The rum was standard strength (40%), so it came as little surprise that the palate was very light, verging on airy – one burp and it was gone forever. Faintly sweet, smooth, warm, vaguely fruity, and again those minerally metallic notes could be sensed, reminding me of an empty tin can that once held peaches in syrup and had been left to dry. Further notes of vanilla, a single cherry and that was that, closing up shop with a finish that breathed once and died on the floor. No, really, that was it.

Next word: “Black”. Baby Rum Jesus help us. Long discredited as a way to classify rum, and if you are curious as to why, I refer you to

Next word: “Black”. Baby Rum Jesus help us. Long discredited as a way to classify rum, and if you are curious as to why, I refer you to

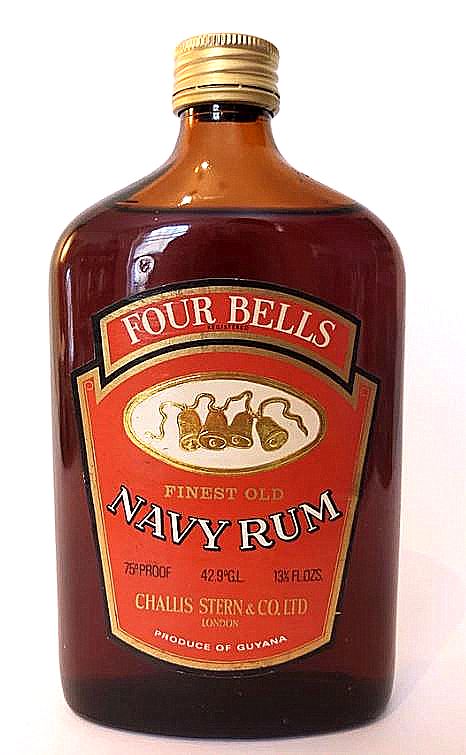

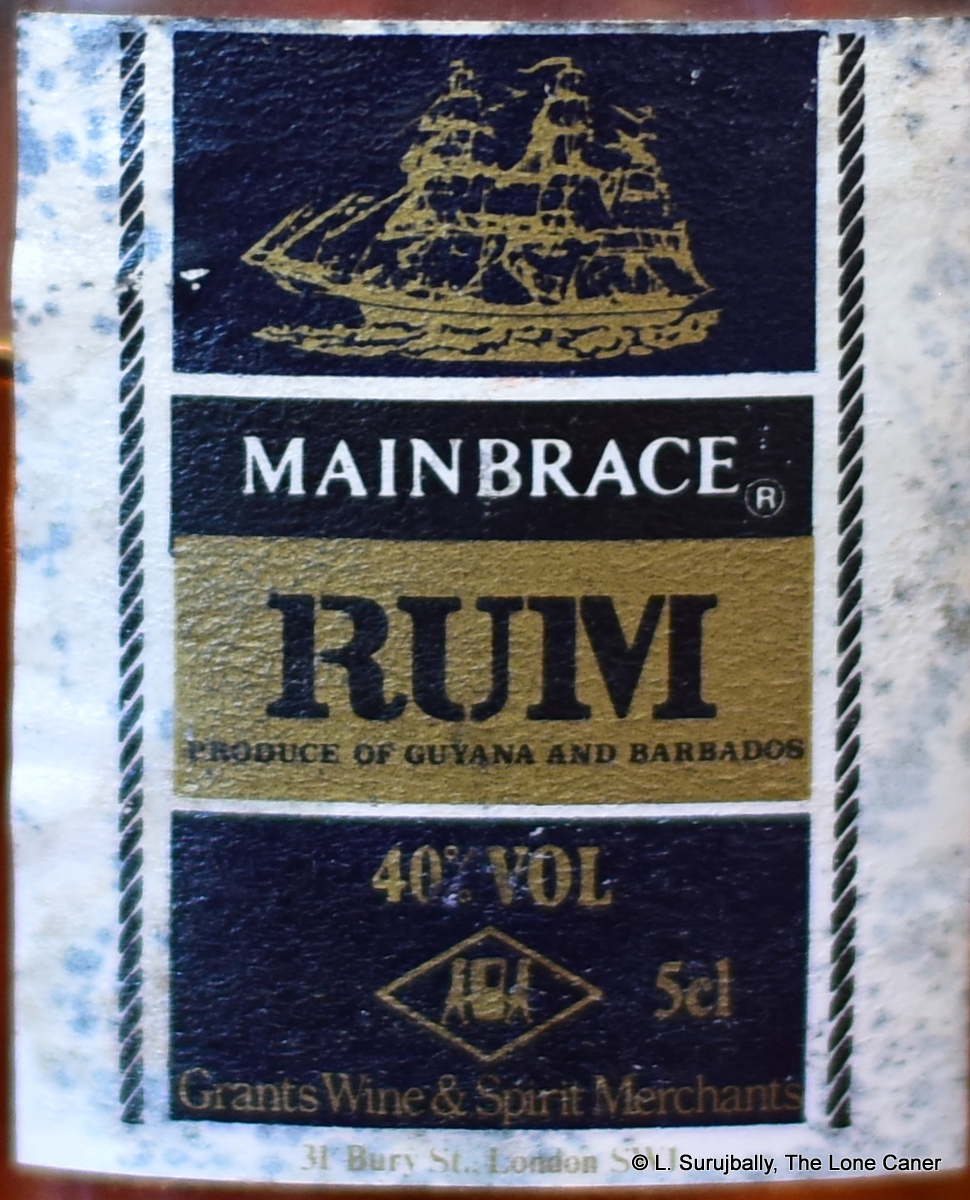

The “Guyana” spelling sets a lower post-independence date of 1966. Grants also released a Navy Rum and a Demerara Rum – both from Guyana, and both at “70º proof”. The address is written differently on their labels though, being “Grants of Saint James” on the Demerara label (Bury Lane is in the area of St. James, and a stone’s throw away from St. James’s Street…and BBR). Grants was still referring to itself as “of St. James” first (and until 1976 at least), but I think it’s the 40% ABV that’s key here, since that only came into effect in the mid 1980s in the UK.

The “Guyana” spelling sets a lower post-independence date of 1966. Grants also released a Navy Rum and a Demerara Rum – both from Guyana, and both at “70º proof”. The address is written differently on their labels though, being “Grants of Saint James” on the Demerara label (Bury Lane is in the area of St. James, and a stone’s throw away from St. James’s Street…and BBR). Grants was still referring to itself as “of St. James” first (and until 1976 at least), but I think it’s the 40% ABV that’s key here, since that only came into effect in the mid 1980s in the UK.