Photo (c) ModernBarCart.com

“White cane spirits are having a moment,” wrote Josh Miller of Inu a Kena in naming the Saint Benevolence clairin one of his top rums of 2019. He was spot on about that and I’ve felt the same way about white rums in general and clairins in particular ever since I had the good fortune to try the Sajous in Paris back in 2014 and had my hair blown back and into next week – so much so that I didn’t just make one list of 21 good white rums, but a second one for good measure (and am gathering material for a third).

Given that Velier’s involvement has raised the profile of clairins so much, it’s surprising that one with the avowed intention of ploughing back all its profits into the community where it is made (see “other notes”, below) does not have more of a mental footprint in people’s minds. That might be because for the most part it seems to be marketed in the USA (home of far too few rum blogs), whence its founders Chase and Calvin Babcock hail – and indeed, the first online write ups (from Josh himself, and Paul Senft on Got Rum), also stemmed from there. Still, it is moving across to Europe as well, and Indy and Jazz Singh of the UK-based Skylark Spirits, couldn’t contain their glee at providing something to a ‘Caner Party in 2019 which we had not seen before and threatening dire violence if it was not tried right then and there.

They could well smile, because the pale yellow 50% “white” rum was an aromatic beefcake that melded a barroom brawler with a civilized Martinique white in a way that we had not seen before. It started rough and ready, true, with fierce and pungent aromas of wax, brine, acetones, and olives biffing the schnozz, and it flexed its unaged nature quite clearly and unapologetically. There was a sprightly line of citrus/white sugar running through it that was pleasing, and after a while I could sense the sharpness of green apples, wasabi, unripe bananas, soursop mixing it up with softer scents of guavas and vanilla. Every now and then the salty, earthy notes popped back up as if to say “I exist!” and overall, the nose was excellent.

Unlike the overpowering strut of the Velier clairins, the taste here was quite restrained and less elemental, even at 50% ABV. In fact, it almost seemed light, initially presenting a nice crisp series of sugar-water and lemon notes, interspersed with salted cucumber slices in sweet apple vinegar (and a pimento or two thrown in for kick). Mostly it was crisp fruits from there – green grapes, red currants, soursop, unripe pears, and it reminded me of nothing so much as the laid back easiness of the Cabo Verde grogues, yet without ever losing a bit of its bad boy character, the way you can always spot a thug even if he’s in a tux, know what I mean? Finish handled itself well – salt and sweet, some tomatoes (!!), a little cigarette tar, but mostly it was sugar water and pears and light fruits, a soft and easy landing after some of the aggro it presented earlier.

All in all, really interesting, though perhaps not to everyone’s taste – it is, admittedly, something of a challenge to sample if one is not prepared for its rough and ready charms. It may best be used as a mixer, and indeed, Josh did remark it would work best in a ‘Ti Punch or Daiquiri. He said it would make “for a fresh take on an old favorite”, and I can’t think of a better phrase to describe not just the cocktails one could make with it, but the rum as a whole. It lends richness and variety to the scope of what Haitian clairins can be.

(#692)(84/100)

Other Notes

- The source of the clairin is the area around Saint Michel de l’Attalaye, which is the second largest city in Haiti, and located in the central north of the country. There, sugar cane fields surround and supply the Dorcinvil Distillery, a third-generation family operation employing organic agricultural practices free from herbicides, pesticides and other chemicals. The cane itself is a blend of several different varieties: Cristalline, Madame Meuze, Farine France and 24/14. After harvesting and crushing, the juice is fermented with wild yeasts for five to seven days, then run through a handmade Creole copper pot still, and bottled as is (I suspect there may be minor filtration to remove sediments or occlusions). It is unclear whether it is left to stand and rest for a bit, but my bottle wasn’t pure white but a very faint yellow, so the supposition is not an entirely idle one.

- The company also produces a blended pot-column still Caribbean five year old rum I have not tried, made from from Barbados molasses and cane juice syrup from the Dominican republic

- Charity Work: [adapted from Inu A Kena and the company website] Saint Benevolence rum is made by Calvin Babcock, who co-founded Living Hope Haiti, a charity providing educational, medical, and economic services in St Michel de Attalaye in Northern Haiti. He works with his son Chase, the other half of the team. Along with their partners on the ground in St Michel de Attalaye, Living Hope Haiti (LHH) has built five elementary schools, four churches, an orphanage, a medical clinic, and funded other critically necessary infrastructure including bridges and water wells. They also provide three million meals per year to those in need. The work of LHH is almost entirely funded by the Babcock family, but with the introduction of Saint Benevolence, a new funding stream has come online. Besides LHH, Saint Benevolence funds two additional charities: Innovating Health International (IHI) and Ti Kay. IHI is focused on treating chronic diseases and addressing women’s health issues in Haiti and other developing countries, while Ti Kay is focused on providing ongoing TB and HIV care. Since 100% of the profits of the rum go straight back to the community of origin, this is certainly a rum worth buying to support such efforts, though of course you’re also getting quite a good and unique white rum for the price.

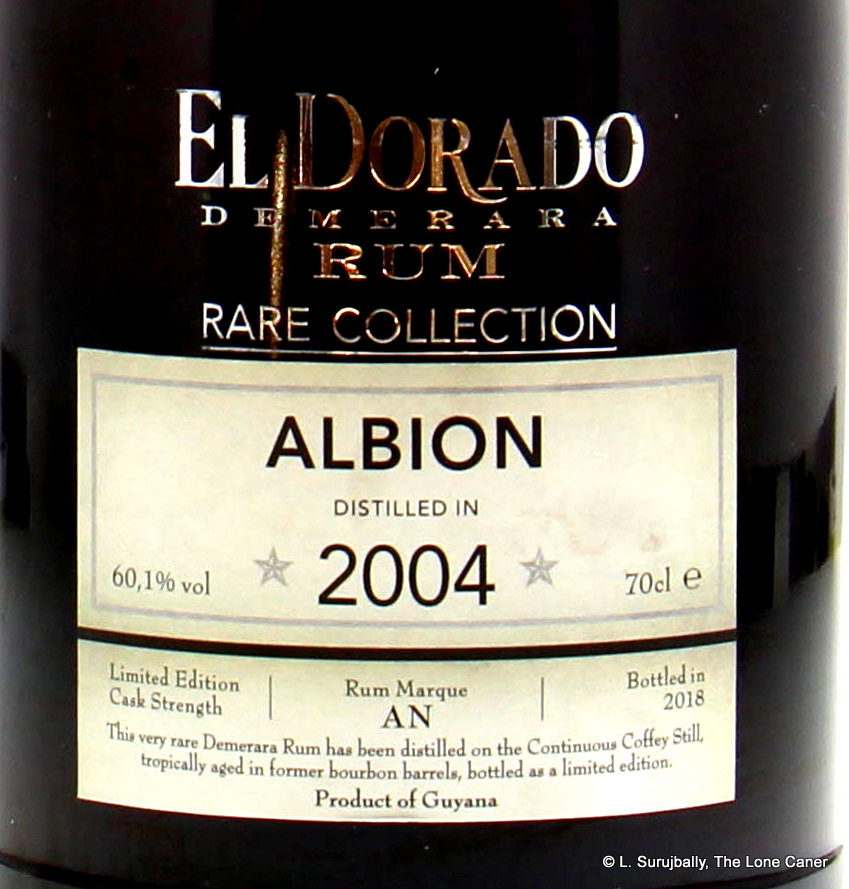

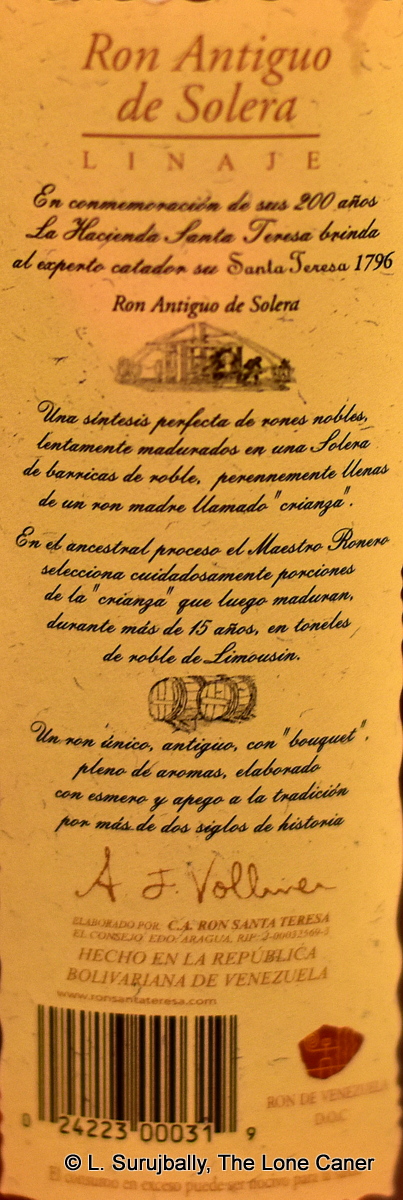

Its standout aspect was how smooth it came across when tasted. As with the Albion we looked at before, the rum didn’t profile like anywhere near its true strength, was warm and firm and tasty, trending a bit towards being over-oaked and ever-so-slightly too tannic. But those powerful notes of unsweetened cooking chocolate, creme brulee, caramel, dulce de leche, molasses and cumin mitigated the wooden bite and provided a solid counterpoint into which subtler marzipan and mint-chocolate hints could be occasionally noticed, flitting quietly in and out. The finish continued these aspects while gradually fading out, and with some patience and concentration, port-flavoured tobacco, brown sugar and cumin could be discerned.

Its standout aspect was how smooth it came across when tasted. As with the Albion we looked at before, the rum didn’t profile like anywhere near its true strength, was warm and firm and tasty, trending a bit towards being over-oaked and ever-so-slightly too tannic. But those powerful notes of unsweetened cooking chocolate, creme brulee, caramel, dulce de leche, molasses and cumin mitigated the wooden bite and provided a solid counterpoint into which subtler marzipan and mint-chocolate hints could be occasionally noticed, flitting quietly in and out. The finish continued these aspects while gradually fading out, and with some patience and concentration, port-flavoured tobacco, brown sugar and cumin could be discerned.

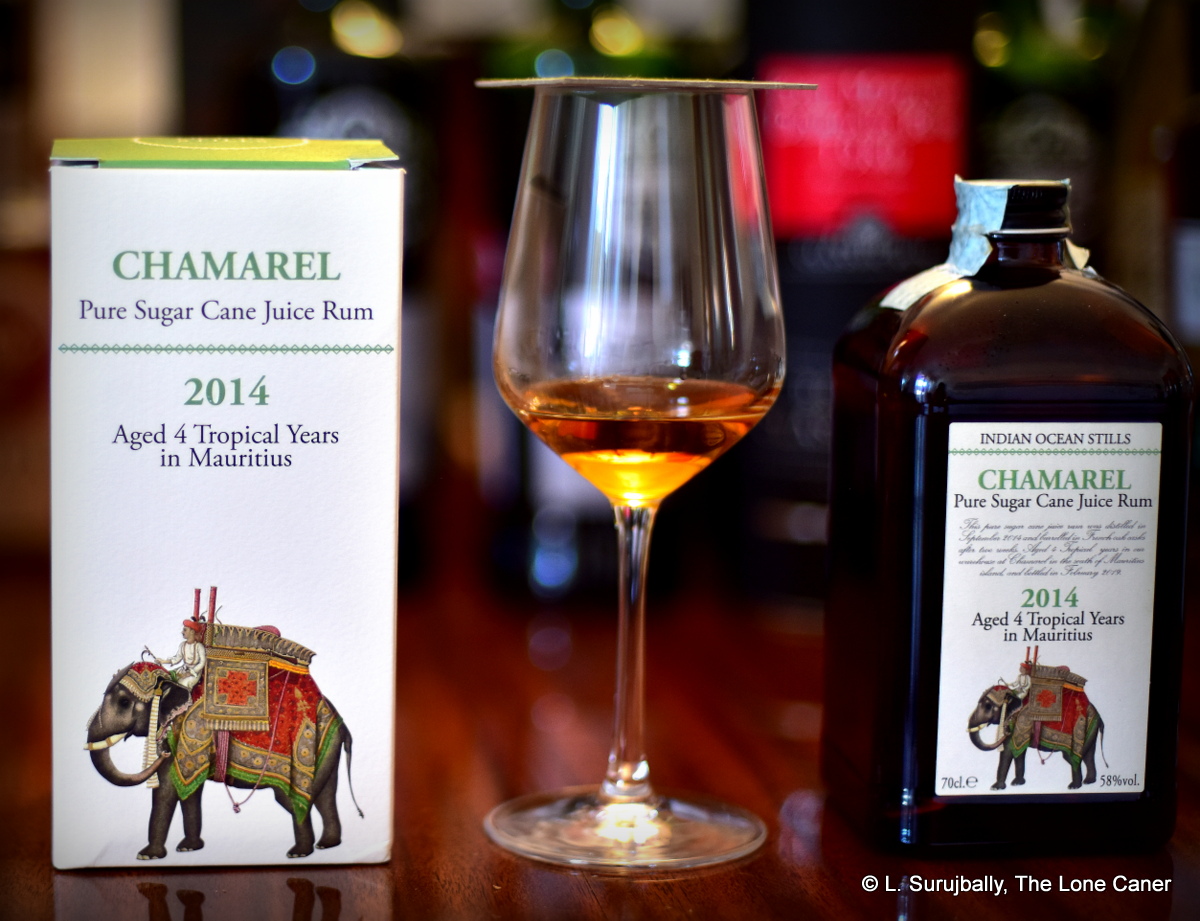

Brief stats: a 4 year old rum distilled in September 2014, aged in situ in French oak casks and bottled in February 2019 at a strength of 58% ABV. Love the labelling and it’s sure to be a fascinating experience not just because of the selection by Velier, or its location (we have tried few rums from there though those

Brief stats: a 4 year old rum distilled in September 2014, aged in situ in French oak casks and bottled in February 2019 at a strength of 58% ABV. Love the labelling and it’s sure to be a fascinating experience not just because of the selection by Velier, or its location (we have tried few rums from there though those  Rumaniacs Review #107 | R-0688

Rumaniacs Review #107 | R-0688 Palate – Waiting for this to open up is definitely the way to go, because with some patience, the bags of funk, soda pop, nail polish, red and yellow overripe fruits, grapes and raisins just become a taste avalanche across the tongue. It’s a very solid series of tastes, firm but not sharp unless you gulp it (not recommended) and once you get used to it, it settles down well to just providing every smidgen of taste of which it is capable.

Palate – Waiting for this to open up is definitely the way to go, because with some patience, the bags of funk, soda pop, nail polish, red and yellow overripe fruits, grapes and raisins just become a taste avalanche across the tongue. It’s a very solid series of tastes, firm but not sharp unless you gulp it (not recommended) and once you get used to it, it settles down well to just providing every smidgen of taste of which it is capable.

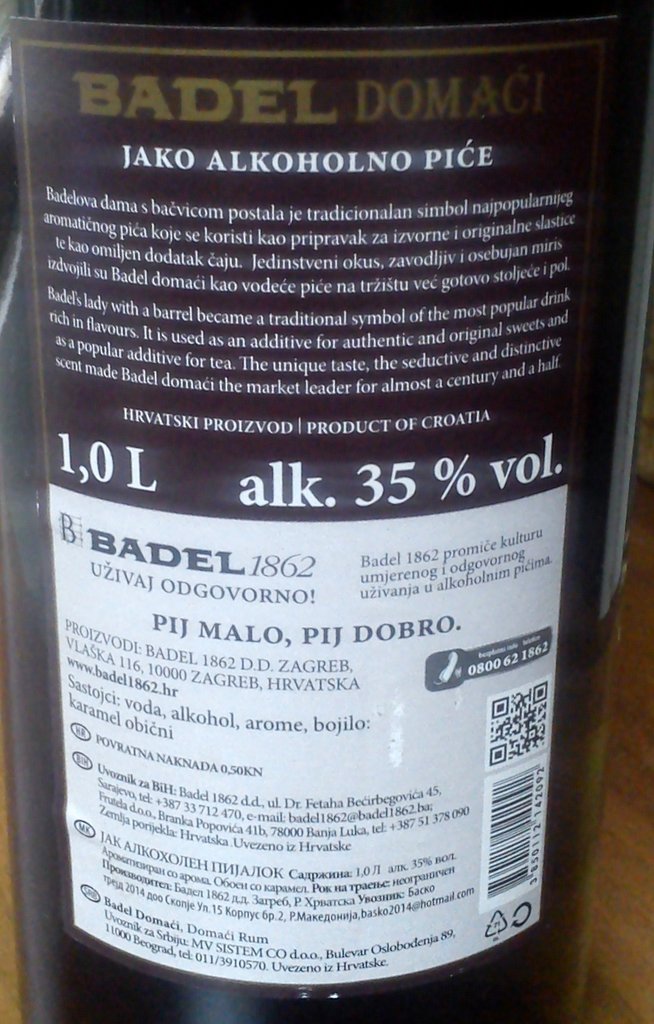

If we accept these data points, then of course the Casino is not, by all current definitions, a rum, and in point of fact, the entry might just as easily be listed in the Rumaniacs page since this version is no longer being made — the word “rum” was either replaced by “room” or dropped completely from the label when Hungary joined the EU in 2004, and that suggests a manufacture for the product I tasted of around 1988-2003 which actually makes it a heritage rum entry, but what the hell.

If we accept these data points, then of course the Casino is not, by all current definitions, a rum, and in point of fact, the entry might just as easily be listed in the Rumaniacs page since this version is no longer being made — the word “rum” was either replaced by “room” or dropped completely from the label when Hungary joined the EU in 2004, and that suggests a manufacture for the product I tasted of around 1988-2003 which actually makes it a heritage rum entry, but what the hell.

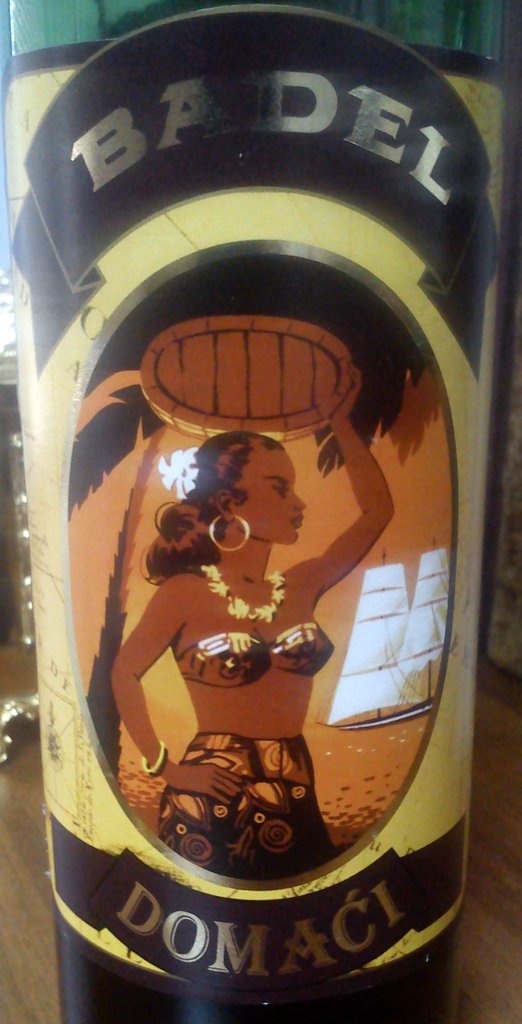

Unsurprisingly it’s mostly for sale in the Balkans — Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia, with outliers in Germany — and has made exactly zero impact on the greater rum drinking public in the West. Wes briefly touched on it with a review of

Unsurprisingly it’s mostly for sale in the Balkans — Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia, with outliers in Germany — and has made exactly zero impact on the greater rum drinking public in the West. Wes briefly touched on it with a review of

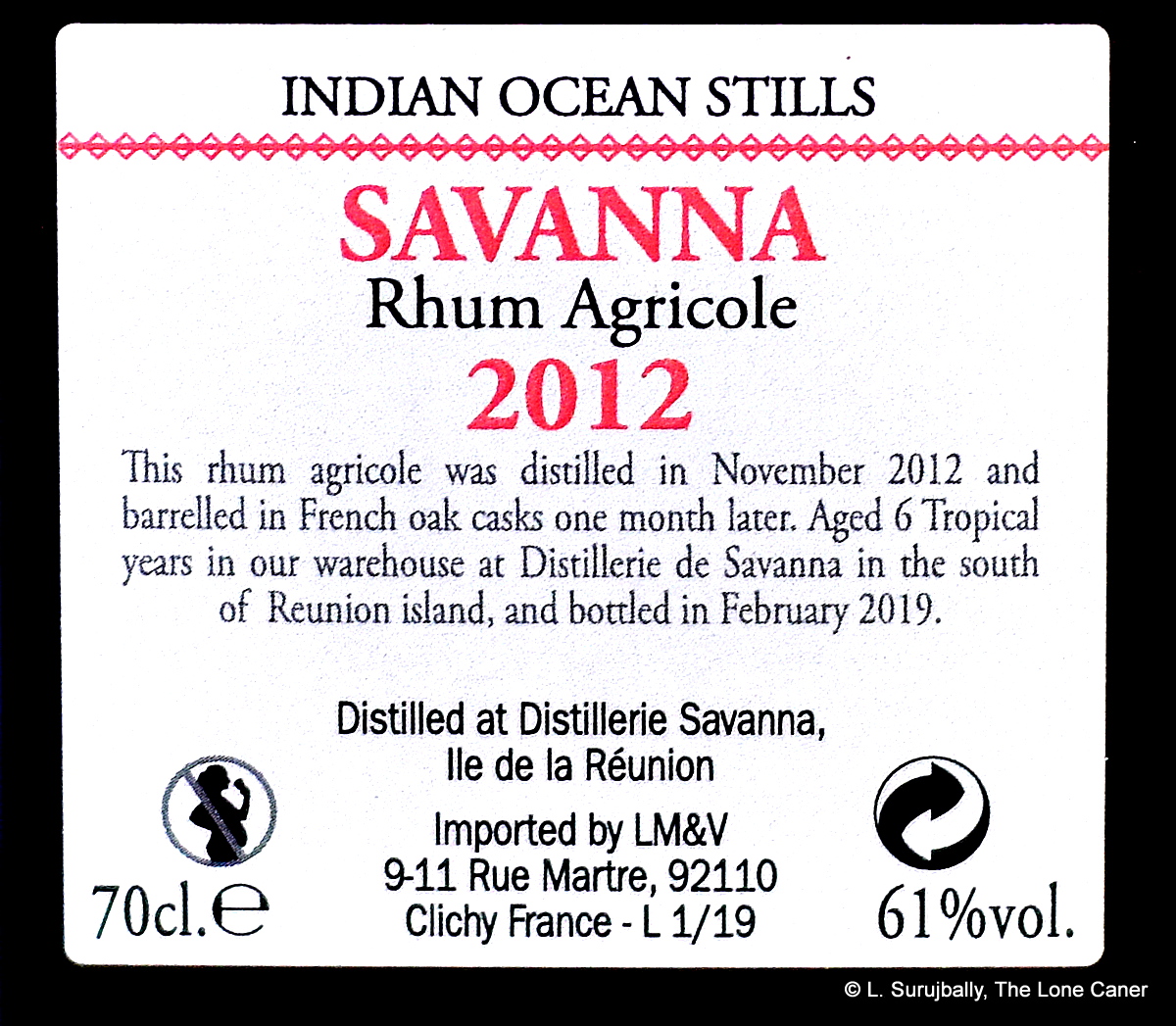

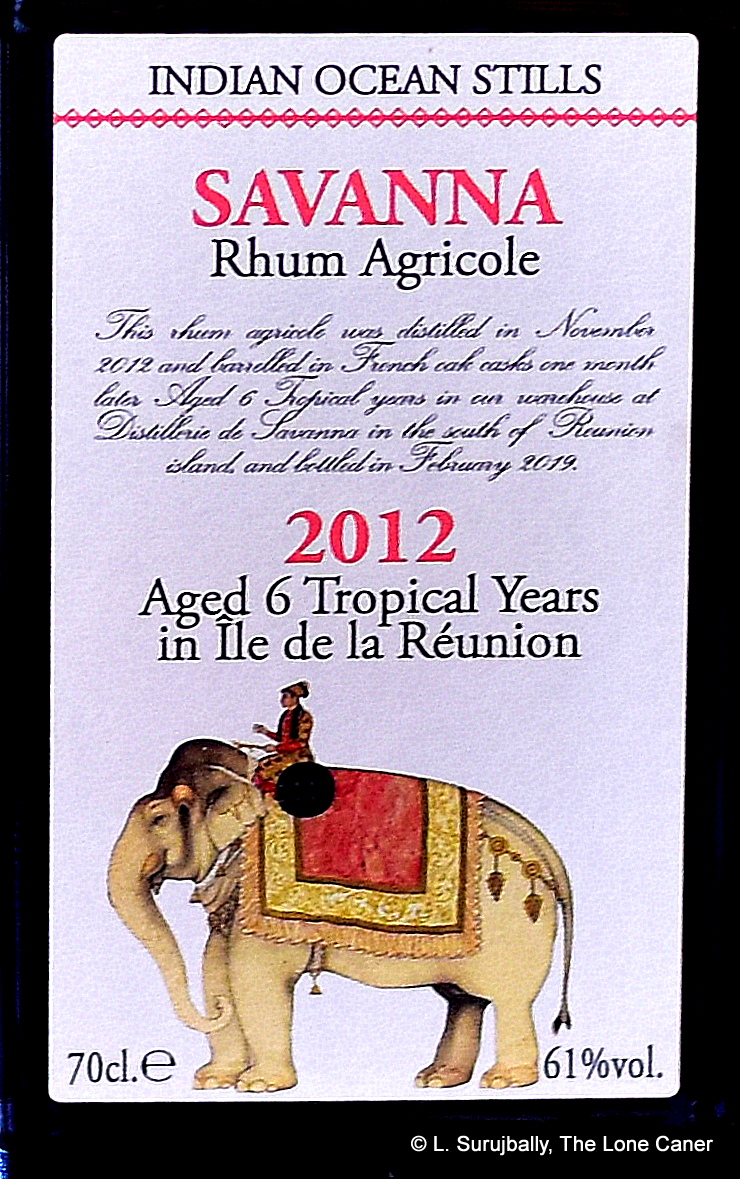

The “Indian Ocean Still” series of rums have a labelling concept somewhat different from the stark wealth of detail that usually accompanies a Velier collaboration. Personally, I find it very attractive from an artistic point of view – I love the man riding on the elephant motif of this and the companion

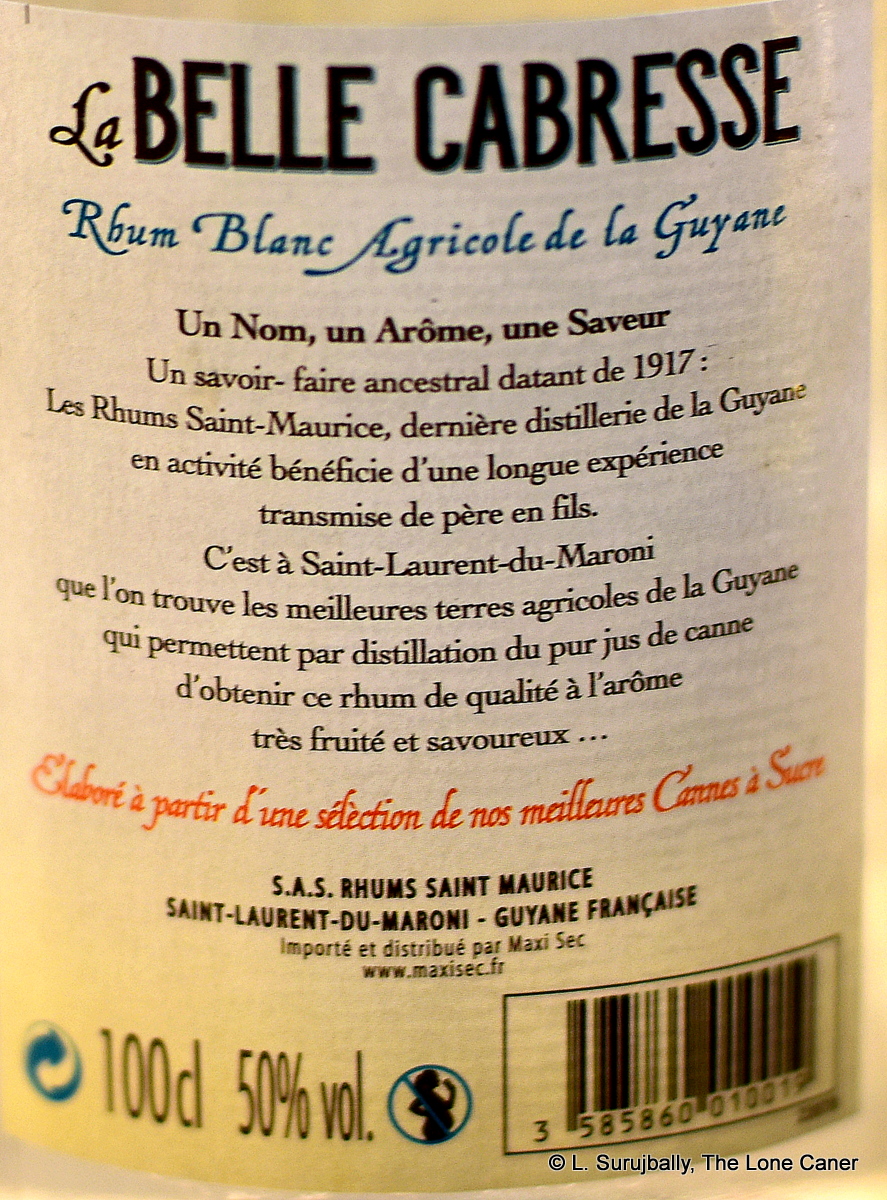

The “Indian Ocean Still” series of rums have a labelling concept somewhat different from the stark wealth of detail that usually accompanies a Velier collaboration. Personally, I find it very attractive from an artistic point of view – I love the man riding on the elephant motif of this and the companion  Man, this was a really good dram. It adhered to most of the tasting points of a true agricole — grassiness, crisp herbs, citrus, that kind of thing — without being slavish about it. It took a sideways turn here or there that made it quite distinct from most other agricoles I’ve tried. If I had to classify it, I’d say it was like a cross between the fruity silkiness of a St. James and the salt-oily notes of a Neisson.

Man, this was a really good dram. It adhered to most of the tasting points of a true agricole — grassiness, crisp herbs, citrus, that kind of thing — without being slavish about it. It took a sideways turn here or there that made it quite distinct from most other agricoles I’ve tried. If I had to classify it, I’d say it was like a cross between the fruity silkiness of a St. James and the salt-oily notes of a Neisson.

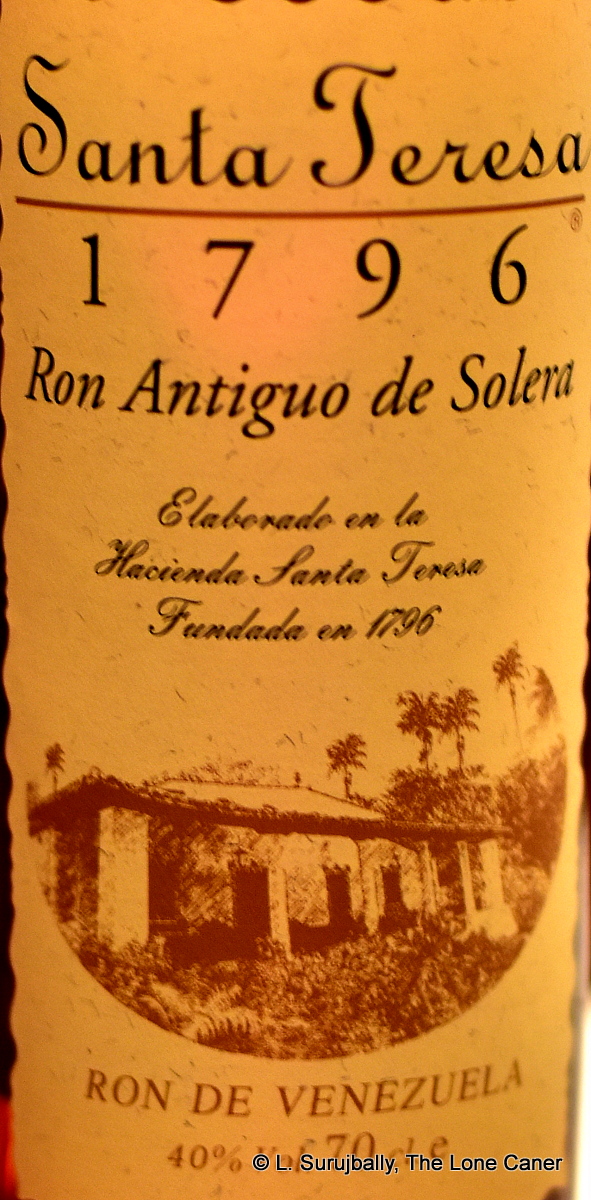

It’s inoffensive in the extreme, there’s little to dislike here (except perhaps the strength), and for your average drinker, much to admire. The palate is quite good, if occasionally vague – light white fruits and toblerone, nougat, salted caramel ice cream, bon bons, sugar water, molasses, vanilla, dark chocolate, brown sugar and delicate spices – cinnamon and nutmeg. It’s darker in texture and thicker in taste than I recalled, but that’s all good, I think. It fails on the finish for the obvious reason, and the closing flavours that can be discerned are fleeting, short, wispy and vanish too quick.

It’s inoffensive in the extreme, there’s little to dislike here (except perhaps the strength), and for your average drinker, much to admire. The palate is quite good, if occasionally vague – light white fruits and toblerone, nougat, salted caramel ice cream, bon bons, sugar water, molasses, vanilla, dark chocolate, brown sugar and delicate spices – cinnamon and nutmeg. It’s darker in texture and thicker in taste than I recalled, but that’s all good, I think. It fails on the finish for the obvious reason, and the closing flavours that can be discerned are fleeting, short, wispy and vanish too quick.

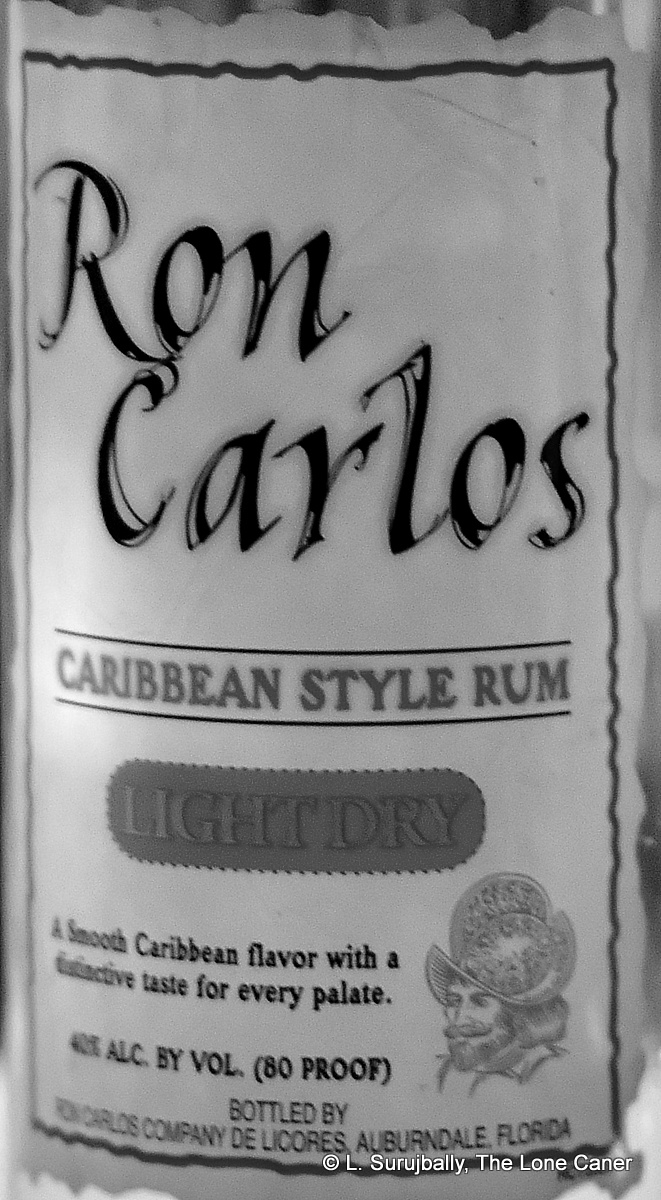

The rum was standard strength (40%), so it came as little surprise that the palate was very light, verging on airy – one burp and it was gone forever. Faintly sweet, smooth, warm, vaguely fruity, and again those minerally metallic notes could be sensed, reminding me of an empty tin can that once held peaches in syrup and had been left to dry. Further notes of vanilla, a single cherry and that was that, closing up shop with a finish that breathed once and died on the floor. No, really, that was it.

The rum was standard strength (40%), so it came as little surprise that the palate was very light, verging on airy – one burp and it was gone forever. Faintly sweet, smooth, warm, vaguely fruity, and again those minerally metallic notes could be sensed, reminding me of an empty tin can that once held peaches in syrup and had been left to dry. Further notes of vanilla, a single cherry and that was that, closing up shop with a finish that breathed once and died on the floor. No, really, that was it.

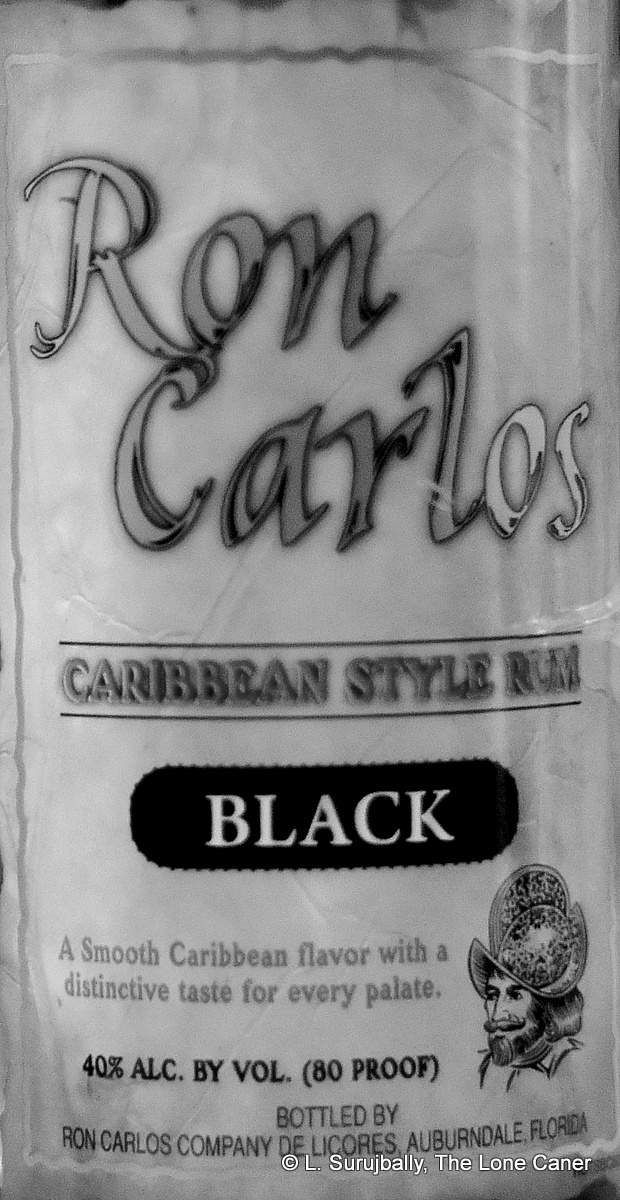

Next word: “Black”. Baby Rum Jesus help us. Long discredited as a way to classify rum, and if you are curious as to why, I refer you to

Next word: “Black”. Baby Rum Jesus help us. Long discredited as a way to classify rum, and if you are curious as to why, I refer you to

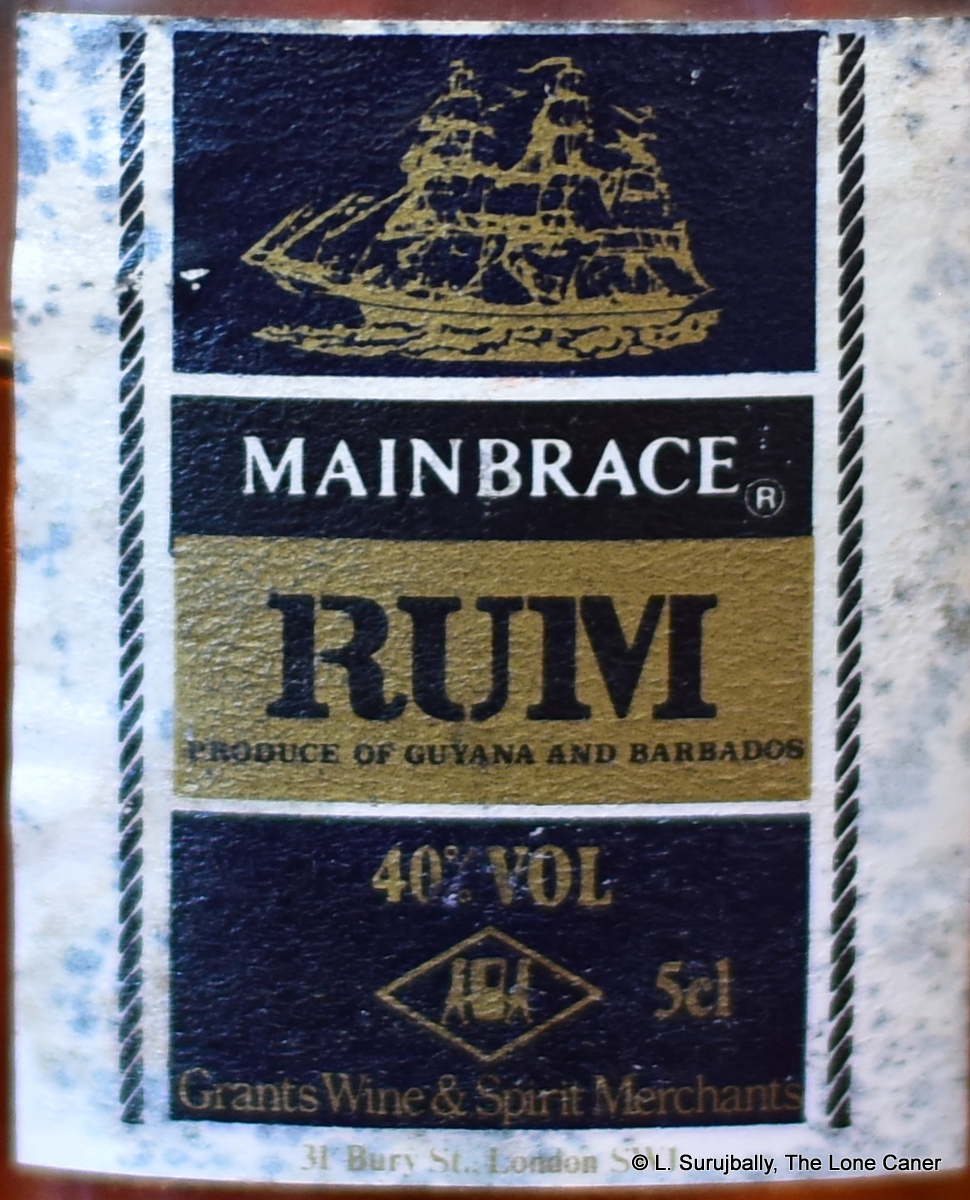

The “Guyana” spelling sets a lower post-independence date of 1966. Grants also released a Navy Rum and a Demerara Rum – both from Guyana, and both at “70º proof”. The address is written differently on their labels though, being “Grants of Saint James” on the Demerara label (Bury Lane is in the area of St. James, and a stone’s throw away from St. James’s Street…and BBR). Grants was still referring to itself as “of St. James” first (and until 1976 at least), but I think it’s the 40% ABV that’s key here, since that only came into effect in the mid 1980s in the UK.

The “Guyana” spelling sets a lower post-independence date of 1966. Grants also released a Navy Rum and a Demerara Rum – both from Guyana, and both at “70º proof”. The address is written differently on their labels though, being “Grants of Saint James” on the Demerara label (Bury Lane is in the area of St. James, and a stone’s throw away from St. James’s Street…and BBR). Grants was still referring to itself as “of St. James” first (and until 1976 at least), but I think it’s the 40% ABV that’s key here, since that only came into effect in the mid 1980s in the UK.

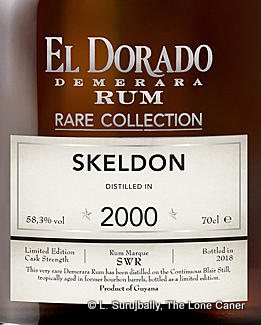

Whatever the case, the rum was as fierce as the Diamond, and even at a microscopically lower proof, it took no prisoners. It exploded right out of the glass with sharp, hot, violent aromas of tequila, rubber, salt, herbs and really good olive oil. If you blinked you could see it boiling. It swayed between sweet and salt, between soya, sugar water, squash, watermelon, papaya and the tartness of hard yellow mangoes, and to be honest, it felt like I was sniffing a bottle shaped mass of whup-ass (the sort of thing Guyanese call “regular”).

Whatever the case, the rum was as fierce as the Diamond, and even at a microscopically lower proof, it took no prisoners. It exploded right out of the glass with sharp, hot, violent aromas of tequila, rubber, salt, herbs and really good olive oil. If you blinked you could see it boiling. It swayed between sweet and salt, between soya, sugar water, squash, watermelon, papaya and the tartness of hard yellow mangoes, and to be honest, it felt like I was sniffing a bottle shaped mass of whup-ass (the sort of thing Guyanese call “regular”). Rumaniacs Review #105 | 0678

Rumaniacs Review #105 | 0678 Nose – A combination of the

Nose – A combination of the  Rumaniacs Review #104 | 0677

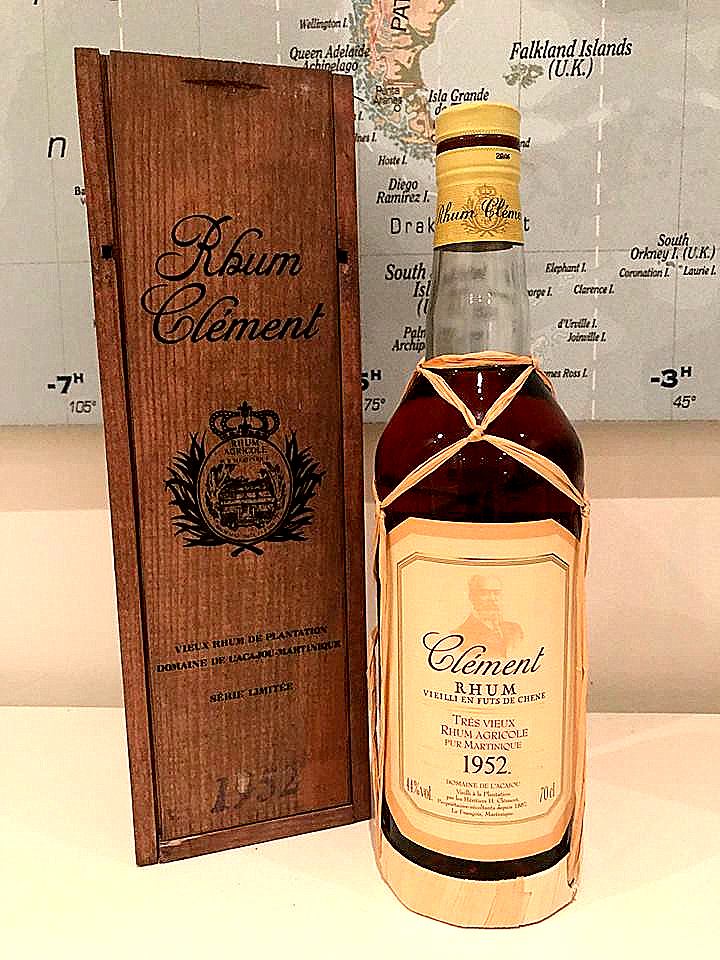

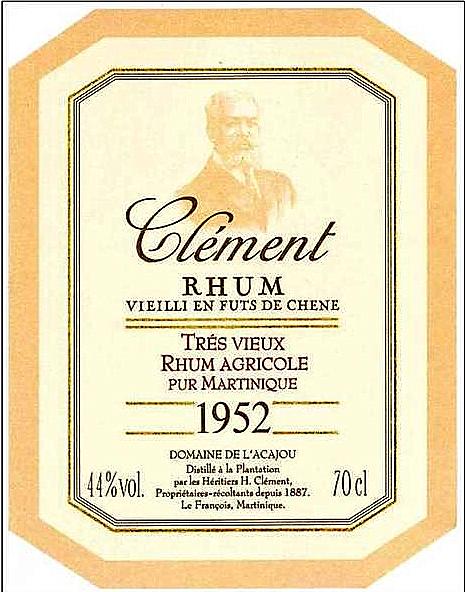

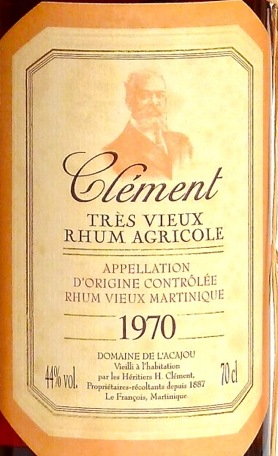

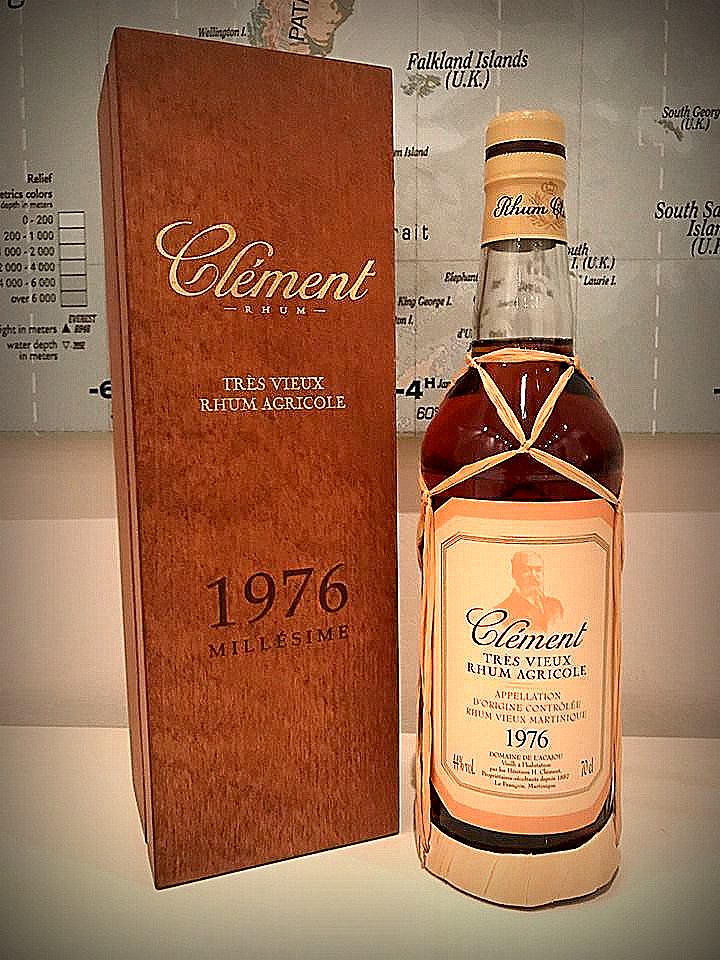

Rumaniacs Review #104 | 0677 Another peculiarity of the rhum is the “AOC” on the label. Since the AOC came into effect only in 1996, and even at its oldest this rhum was done ageing in 1991, how did that happen? Cyril told me it had been validated by the AOC after it was finalized, which makes sense (and probably applies to the 1976 edition as well), but then, was there a pre-1996 edition with one label and a post-1996 edition with another one? (the two different boxes it comes in suggests the possibility). Or, was the entire 1970 vintage aged to 1991, then held in inert containers (or bottled) and left to gather dust for some reason? Is either 1991 or 1985 even real? — after all, it’s entirely possible that the trio (of 1976, 1970 and 1952, whose labels are all alike) was released as a special millesime series in the late 1990s / early 2000s. Which brings us back to the original question – how old is the rhum?

Another peculiarity of the rhum is the “AOC” on the label. Since the AOC came into effect only in 1996, and even at its oldest this rhum was done ageing in 1991, how did that happen? Cyril told me it had been validated by the AOC after it was finalized, which makes sense (and probably applies to the 1976 edition as well), but then, was there a pre-1996 edition with one label and a post-1996 edition with another one? (the two different boxes it comes in suggests the possibility). Or, was the entire 1970 vintage aged to 1991, then held in inert containers (or bottled) and left to gather dust for some reason? Is either 1991 or 1985 even real? — after all, it’s entirely possible that the trio (of 1976, 1970 and 1952, whose labels are all alike) was released as a special millesime series in the late 1990s / early 2000s. Which brings us back to the original question – how old is the rhum? Rumaniacs Review #103 | 0676

Rumaniacs Review #103 | 0676

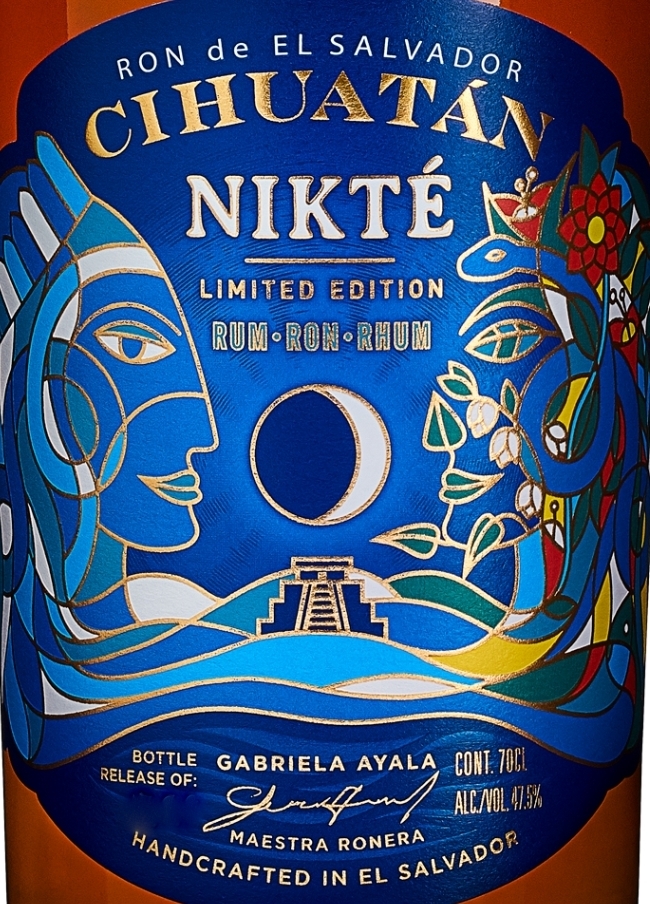

The name of the rum (or ron, if you will) relates back to the Mayan motif that has been part of the brand from the inception:

The name of the rum (or ron, if you will) relates back to the Mayan motif that has been part of the brand from the inception:

The rhum presents as warm rather than hot or sharp, so relatively tame to sniff, and this continues on to the palate. There a certain sweetness, light and clear, that is more pronounced in the initial sips, and the citrus notes are more noticeable, as are the brine and slight rottenness. What’s most distinct is the emergent strain of ouzo, of licorice (mostly absent from the nose until after it opens up a bit) … but fortunately this doesn’t take over, integrating reasonably well with tastes of clear bubble gum and strawberry soda pop that round out the crisp profile. Finish is medium long, dry, sweet, warm Guavas and white fruits and watery pears mingle with oranges and citrus peel and a slight dusting of salt, and that’s just about the whole story.

The rhum presents as warm rather than hot or sharp, so relatively tame to sniff, and this continues on to the palate. There a certain sweetness, light and clear, that is more pronounced in the initial sips, and the citrus notes are more noticeable, as are the brine and slight rottenness. What’s most distinct is the emergent strain of ouzo, of licorice (mostly absent from the nose until after it opens up a bit) … but fortunately this doesn’t take over, integrating reasonably well with tastes of clear bubble gum and strawberry soda pop that round out the crisp profile. Finish is medium long, dry, sweet, warm Guavas and white fruits and watery pears mingle with oranges and citrus peel and a slight dusting of salt, and that’s just about the whole story.

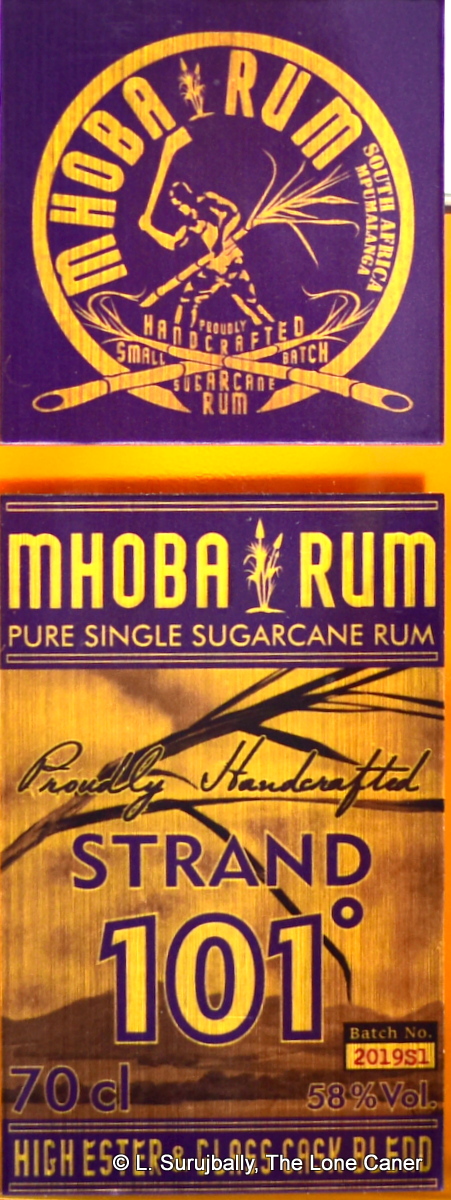

The Strand 101° was specifically designed by Knud Strand, a colourful Danish distributor who worked closely with Robert Greaves (as he had with many brands before) to bring the Mhoba line to market. What he was looking for was to create a blend of unaged and aged rum from pot stills, adhering to something of the S&C profile but from only one still (not two or more). He was messing around with samples some time back and after making his selections finally came back to two, both fullproof — one, slightly aged was too woody, with the other unaged one perhaps too funky.

The Strand 101° was specifically designed by Knud Strand, a colourful Danish distributor who worked closely with Robert Greaves (as he had with many brands before) to bring the Mhoba line to market. What he was looking for was to create a blend of unaged and aged rum from pot stills, adhering to something of the S&C profile but from only one still (not two or more). He was messing around with samples some time back and after making his selections finally came back to two, both fullproof — one, slightly aged was too woody, with the other unaged one perhaps too funky.