Introduction

Lists are great. I love good lists. I’m a complete list junkie. I collect lists. As a blogger and a writer, I find myself not only perusing them, but making them (lists of lists, so to speak) and have several of my own in my personal faves collection, and somewhere in there I have a list of the ten best lists as well…as well as, no surprise, the ten worst. Even when I despise the nonsense in a list, I can’t help but read it right to the bottom.

Lists, however, have to be approached with some caution. From the prevailing comments over some of the “Ten Best…” lists I have seen over the last few years, it’s clear that the misconceptions of what they are, and the understanding of their very real limitations, is not always clearly understood. So today let’s examine the matter in somewhat more detail.

First of all, what kinds of lists are we talking about? For the purpose of this opinion I classify them as follows:

- Magazine Lists

- Award Winners’ Lists

- Bloggers Lists

- Any other lists

We’ll examine each in their turn to see the issues that they have.

Magazine “Best of…” or “…To Try” Lists

These are list pulled together by people who generally have exactly zero standing in the rum community. They do not contribute, do not engage, and are usually unknown (we all know who the real commentators on and contributors to the great discussions of our time are). For the most part they are self-styled, self-annointed and self-appointed “lifestyle” or “food and drink” “ambassadors” who are trying to make a buck, which is fine, but lack much in the way of credibility, which isn’t.

The origin of such lists varies. Some are commissioned. Some arise organically. Few if any can be trusted, as this exchange on FB showed, when asked with a mixture of irritation and pathos, what the ten best rums in the world were. A list recently went up speaking about countries making the world’s best rum. And to show the utter unkillabitility of the idea of lists, in January 2021 Uproxx.com posted an epically useless list with the grandiose title of “10 Bottles of Rum Actually Worth their $90 price tags,” and Delish, not wanting to be left out, produced an almost equally cringe-worthy exhibit of their own, this one, clearly showing that list makers’ moronic tendencies and sloppy research had not only hit rock bottom but was actively questing for shovels (FB denizens took the two lists apart here and here). These lists were equalled only by the Gentleman Journal which produced one called “The Best Bottles of Rum to Challenge your Inner Hemmingway” which a merciful netizen had the sense to only post to the FB Spiced Rum Club which is pretty much where it belonged.

One silly list of “ten best rums” I remember from several years back ended up being the writer talking to a bartender on a cruise and regurgitating it wholesale. Another list was heavy on the South American rums – many of which I had never heard of before – and when a deeper check into the background of the author was done, it became clear that he was in fact a resident of those parts, knew little else, but conveniently made no disclaimer or acknowledgement of the list’s limitations – it was just dumped out there. Whether a fest or an institute, a published author or an online blogger or a lifestyle writer, then, the limitations of the list must be included, but rarely are (and this is why one of the few such productions I ever cared for was Tony Sachs’).

The reason such lists are dangerous is because they purport to be educational, but are nothing of the kind. They present their information without context, try to reduce a very complex subject of enormous breadth to clickbait … and thereby pretend to an authority they do not possess, and have certainly not earned. It’s not always clear whether the authors have even tried the rums they hawk, or are merely shills for freely provided marketing copy. But by their very popularity they crowd out better lists that are actually made with some level of thought (like here and here). No wonder rums get no respect, when people masquerading as experts keep churning out trash of this nature….and continue to get read by new entrants to the field who are seeking information and imbibe the misconceptions such lists promote.

The important thing to understand about such lists is that in most of such cases, the currency of the realm is not imparting knowledge, not presenting a slice of a great sample set, not imparting understanding, but selling clicks: expertise is therefore irrelevant. This is why so many of the ones published month in and month out so reliably retain the rich fecal odour of indifferent if not actually negligent research and just about zero knowledge of the field.

My advice to readers of such lists is to read them, yes (after all, who am I to tell you not to?) but always walk in with your own critical thinking hat on, and come armed with the cynical skepticism of a jaded streetwalker. At best it’s entertainment. At worst it’s a cynical exercise in holding your attention. Just be aware of that.

Award Winner’s Lists

A much better indicator of quality in list-making of rums to try / buy / source / know about is often seen to be lists of medal or award winners. The tradition of such competitions, more than a century old, helps justify purchasing decisions made by consumers, and are plumes in the hats of distilleries that win. Within this band of lists are two variations:

[1] A Winner’s List developed by some kind of institute, society or organization that supposedly represents spirits (or the rum category) as a whole, like the Beverage Tasting Institute, World Rum Awards, ISWC, ISC, ISS or what have you.

On a purely theoretical basis, these things are great. Industry experts are tapped to lend their expertise in aggregate, coming together to rate rums. Then they spend time doing the tastings blind within the categories and medal winners are selected based on the summing up or averaging out the points received from each judge. What’s not to admire?

I don’t mean to pan the exercise, which I do believe is a useful one. What I do want to emphasize, however, is that they have limitations, and we should be cognizant of – and preferably told – what they are. Exactly what is being won here? By whom, against what, how many, using what criteria? In other words, if the Caputo 1973 wins the Best-In-Class Double-Gold award (which it has), consider these questions, so rarely asked, so rarely provided:

- What exactly is the Class? What is the definition?

- If there is a Double Gold there must be a Single. Who won that? Is there a Triple?

- What did it win against? What were the other rums in contention? How many? What did they win? Did all, some, or none win?

- How many rums were in competition in total? What is the entire sample set by company, country and brand?

- Did the entrants have to pay to get their rums into competition?

- Which known and famed brands within the classes did not enter?

- Over what period of time did the judging take place? Where? Under what conditions?

- Who were the judges?

Clearly, there are gaps in the knowledge of consumers as to what exactly the medal or award or the ranking represents and how it was arrived at. Unfortunately, in a world where memes, sound bites and snappy McNuggets of phrasing are what passes for news, the only thing people see and digest is “XXX won YYY!!! Huzzah!” when a favourite wins, and and furious or anguished “WTF????!!” when it doesn’t, and they go no further…and if you doubt that, feel free to observe what happens when Foursquare wins something, or doesn’t.

[2] Secondly, there are medal winner lists put out by a rum festival based on its panel tastings

Here, rum festival organizers compile awards lists which are based on actual ranked scores of rums as put together by a tasting panel working in tandem over several days. The intentions are good, and again, I like them, and feel they are useful for laypeople to make more informed decisions.

As before, however, such tasting awards have their limitations, as the questions on organizations’ efforts above make clear. Many of the issues mentioned above are equally applicable here.

For one, I feel strongly that nobody, no matter how good, can taste the 50+ or so rums per day he needs to, in sessions of say six hours per day, over a two- or three-day period, and maintain any kind of objectivity and sensitivity. It’s simply impossible to avoid palate fatigue, something I know from personal experience. Even assuming all one has to do is spend a minute or two on each and then rank them 1,2,3,4…., is that even fair, given how rum, like any other strong spirit, rewards a rather more painstaking, leisurely examination? (I agree this is a personal opinion, but then, that’s what this whole essay is).

Secondly, in rumfest competitions as for institutes, only rums that enter get judged, and in many festivals, they have to pay to get there (this is often a feature of institutes as well). Since most rum companies — especially the new, small and relatively unknown ones — are on a tight budget, they clearly can’t go to all of the competitions in the world (even if a rumfest organizer keeps entry fees low) and so something will obviously get missed. With 10,000+ rums in the world, of which several thousand are current and made by hundreds of producers all over the globe, I leave it to you to wonder at exactly how many brands and producers have their rums in any competition, and what worth the eventual winners have, when so much must – must! – be excluded.

This leads straight into the associated question applicable to both rumfest competitions and institutes awards, which is: if something wins, then what was the competition? What are the other candidates in the class or category? Clearly if something wins a gold medal in its class, one’s opinion of the win and its importance would vary depending on whether it beat a single other entrant, or ten, or fifty. Yet we are almost never told what the winner beat to rise to the top (let alone how many) – at best, we get the two or three runners-up and also-rans to provide context, which I submit is insufficient.

Lastly, consider that there’s the whole issue of classification and how rums fit into categories. In spite of the Cate Method and the Gargano System and the various other individualized criteria by which rums are judged, it’s never entirely consistent between and among the various organizations — and that means that the medal results from any two competitions will never be entirely comparable and consistent and if you can’t compare them, what good are they? Richard Seale rather caustically remarked of one rum festival competition several years ago, that the way the classifications were set up meant he could enter a single one of his rums in four separate categories, which nicely summarizes the issue.

It certainly points to the need to come up with a globally applicable classification system for rum, but the paradox of the matter (from the perspective of judging, awards and rankings) has always been that the better the system, the more categories there have to be…and the fewer entrants for medals there would consequently be in any category. Nobody has ever come up with a way to square that circle.

What this means, then, is that while awards lists have their uses, they operate within certain constraints and ignoring the context of these limitations can skew one’s perception of what the title of “Best In Class “or “Platinum” or “Double Gold” actually means.

Perhaps a long term project of the industry and its adherents would be to come up with a single rankings mechanism that all institutes and fests adhere to without exception. Then, not only would all the rankings be equivalent, but so would the categories, and therefore the comparability of all rums which would be rated according to completely consistent criteria. I can dream, I guess (and that’s yet another opinion right there).

Blogger’s Lists

Unsurprisingly perhaps, given that I’m one myself, I much prefer blogger’s lists (and in this broad definition I’m including video blogs and podcasts). These can run the gamut of Best of Year lists such as RumCask solicits every year from the blogosphere, or The Fat Rum Pirate’s annual listing, or stuff that just takes rum knowledge in whole new directions.

What I particularly like is those lists they make which go off on a tangent, or show how the lists should be done. There aren’t too many of these, unfortunately but consider TFRP’s “Worst Ten Rums…So Far” list, or its companion of The Top Ten…So Far and the brilliantly edited Top Ten Best Rums In The World, Ever Ever Part 1 and Part 2 which I regularly reread. The Rum Barrel Blog published a nice piece on Top 10 Value For Money Rums and being a barman, also added his own 7 Favourite Daiquiri White Rums. The vlogger Simon Ruszala of the New World Rum Club posted some neat educational lists like a rundown of the Foursquare ECS range and another of the Hampden marques that are less lists than slices of the rum world taken to detail; and that Grand Old Stalwart of the vlogging whisky scene, Ralfy, has a fair bit on his channel as well. And as if that isn’t enough, Rumcast, the relatively new podcast run by Will Hoekenga and John Gulla, intersperses its deep-dive interviews with occasional ruminations of its own such as Six Underrated Rums, Disappointing Rums, 2020 Year In Review, and Nine Recommended Rum Resources.

Clearly there is an equal number of rum or whisky people doing lists as others from less reputable sources, but why do I prefer them, and what makes them, to my mind, better?

Well, for one thing, I know many of them, so that gives them instant credibility – their writing or podcasts or videos go back many years and their interactions in the rumisphere are based on real knowledge amassed over long periods – it’s not just some quick google search lacking depth or substance as plagues far too many of the lists discussed in the earlier section. Moreover, money is not the direct motivator for them (as it is for freelance or staff listmakers writing for online magazines), so they are free to not only chose whatever subject they feel like, but to take it in any direction and at any length they please.

Lastly, they tend to be more honest: they provide context, they explain their choices, and if they sometimes leave out their biases, well, I’ve been following most for extended periods and I am aware of the occasional weaknesses in one direction or another, and why they feel the way they do. I have more information to go on and can form a more educated opinion on the credibility and veracity of whatever list they are putting together. There is, in short, a whole lot less to beware of here and that even goes for a much-panned list like the Howler’s Top 100 of 2017 the reaction against which was so virulent that he retired from Facebook (which I thought was unfair since if you followed his work from 2009 you’d know what he was all about and by that standard his list made sense…but I digress).

Other Lists

The lists described above are pretty much 99% of what is produced. There are Top Lists, Slice-of-the-Subject Lists or To-Try lists for the most part, and engender more trust, or less, depending on who is writing.

Few go further than these, although I’ve tried to do so on my own account by putting out some that have little subjective biases but are reasonably factual all the way through and just interested me personally: among others there is Some Rum Trivia, Movers and Shakers of the Rum World, 12 Interesting Bottle Designs and 21 of The Strongest Rums in the World. I looked around other sites for more examples but didn’t find any that weren’t already covered by the other points above (but feel free to correct me and I’ll amend the section).

Other Issues About Lists To Watch Out For

The business about the Rum Howler above relates to a point not often considered, which is the impact these lists have — not on the listmakers, but the list readers, and then the list commentators. I don’t particularly like the partisan politics they engender on social media via the chatterati, and the occasional verbal violence they promote when an award goes to a Good Rum Producer versus a Bad One, or vice versa. This is almost always sparked by the people commenting on those lists, either in support or in dispute, and do the average Joe — who just wants a damned recommendation so he doesn’t waste his money — few favours.

Take these disparate lists that came out in the last year: one was the nine best rums of the ISWC 2020, which was trumpeted by all the usual acolytes and rum fanciers as being a win for the two distilleries who each had three reps on that list (it got even louder in 2021 when one distillery, Foursquare, won five awards). Do this mental exercise – what would the reaction have been if Plantation had won Instead of Foursquare?

The complete doe-eyed innocent trust (observe the delicate phrasing) which so many otherwise smart and cynical people display when their favourites are on the line is one of the most disturbing trails of detritus that such lists leave in their wake. You can bet your bottom dollar that any list that has a Bumbu, Zacapa, Don Papa or Plantation rum on it can surely be accused of being in the pocket of the list maker, bought or otherwise compromised, or judged by incompetent, paid-for shills who don’t know anything (that last one is always good for a retread).

Yet the same people who make these statements with the such assurance and moral rectitude, cheerfully let their cynicism walk out the door when their favourite distillery is doing the winning. Their boy won, so it’s all good. Let some current pet hate cop a prize, and it’s clearly a deep-state conspiracy by the forces of Mordor using the dark side of the force to sway the gullible to the side of Voldemort. That they themselves are the gullible inhabitants of personal echo chambers where dissent never enters and alternatives are never discussed is a thought too terrible to contemplate, apparently, and the irony floats gently past.

So all this does is create virulent camps of Them and Us in the rum world, which I argue does rum more harm than good. It spreads from producers to bottlers to writers to pundits to commentators to consumers and back again, and nobody is immune. Everyone gets involved either in defense of their favourites or slandering their enemies. When the mud starts flying in this way (for or against a list), the first thing to depart the scene is the understanding that lists by their very nature are subjective or limited (or both): they reflect the tastes of the listmakers or the limited entrants of a competition. I’d much prefer we argue their merits – or lack thereof – seriously and courteously and with facts, than just get involved in rancorous discussions that have no end and do no more than poison the well for all who come after.

Conclusion

Lists, then, even as Top Tens, Bottom Tens, Recommendation or Award Winners, demonstrate complete uselessness at revealing either the best of everything or the winners of anything for the imbibing population at large. The world of rum is too enormous to be encapsulated into a small number, and way too complex for convenient summarization. The palates and experiences of the consumers are too varied and individualistic to be nailed down with anything as simplistic as a short list. It is amazing that even having considered all the points above, lists continue to exercise as subversive and compulsive an attraction as they do.

But admittedly, when done right and well, lists of any stripe amuse and educate in equal measure. They point to avenues that may have been overlooked, or highlight an issue not considered. They are bellwethers and indicators of others’ points of view, and with the ever-increasing homogeneity of social media groups where only agreed to points of view prevail, it’s nice to have a contrary data point pop up now and then. Good lists can inform purchasing decisions, alert one to new choices. The best ones list a selection of a very tiny slice of the rumworld (like, say, the ten worst lists, ten blackest rums or a mashup of ten rums from a particular country or company) and run with it.

So all the preceding taken into account, just use lists with caution – bearing in mind all the preceding remarks on their limitations. Certainly they provide a sense of the world, and act as general guide or signpost, but none should be taken as gospel; and a clear-eyed understanding of what they are, what they represent and — just as vital — what they exclude, is, to me, the sine qua non of appreciating them best. And that leads to a more informed and critically-aware, thinking readership, whose own experiences and judgement should in the final analysis determine what to buy, or what to put one’s commentary behind.

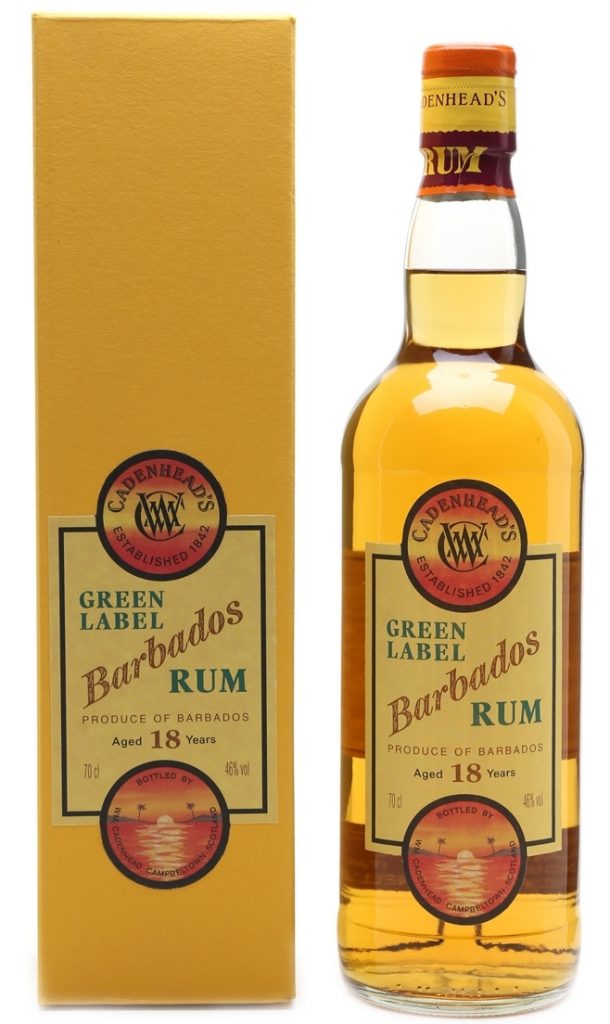

The subject of today’s review is a Green Label Barbados. This is not the first time that this series (which Cadenhead releases without schedule, rhyme or reason) has had a Barbadian rum in it: in fact, I had looked at a Barbados 10 year old back in 2017. There are at least seven rums that I know of in that series, not counting the full strength “Dated Distillation” collection, and I think they have an entrant from every distillery on the island between the two collections except St. Nicholas Abbey (which doesn’t export bulk). Most of the Greens are from WIRD or Mount Gay, while Foursquare is rather better represented of late in the DDs.

The subject of today’s review is a Green Label Barbados. This is not the first time that this series (which Cadenhead releases without schedule, rhyme or reason) has had a Barbadian rum in it: in fact, I had looked at a Barbados 10 year old back in 2017. There are at least seven rums that I know of in that series, not counting the full strength “Dated Distillation” collection, and I think they have an entrant from every distillery on the island between the two collections except St. Nicholas Abbey (which doesn’t export bulk). Most of the Greens are from WIRD or Mount Gay, while Foursquare is rather better represented of late in the DDs. The rum as a whole is not unpleasant at all, and yes, it’s Rockley style — if you were to retry the SMWS R6.1 from 2002 (“Spice at the Races”) and then sample a few Foursquares and a MG XO, the difference is clear enough for there to be little doubt. Surprisingly, Marius felt the herbal and honey notes predominated and pushed the fruits to the back, while I thought the opposite. But he says and I inferred, that this is indeed a Rockley.

The rum as a whole is not unpleasant at all, and yes, it’s Rockley style — if you were to retry the SMWS R6.1 from 2002 (“Spice at the Races”) and then sample a few Foursquares and a MG XO, the difference is clear enough for there to be little doubt. Surprisingly, Marius felt the herbal and honey notes predominated and pushed the fruits to the back, while I thought the opposite. But he says and I inferred, that this is indeed a Rockley.