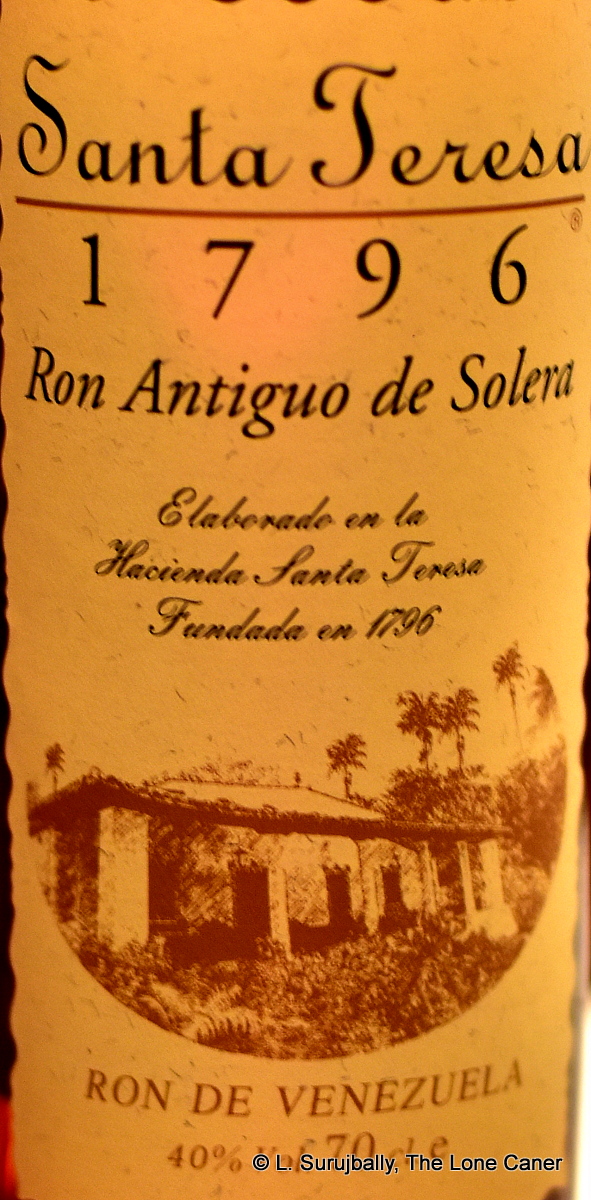

After all these years, there isn’t an average imbiber who hasn’t tried the Venezuelan Santa Teresa Ron Antiguo de Solera 1796 (to give its full and somewhat unwieldy title) at least once. It’s a solera rum which usually sets alarm bells ringing for those who want both more disclosure and less additives, but somehow Santa Teresa has managed, through all the years, to navigate the treacherous shoals of too much or too little and remained a consistent, if not top tier, favourite of the entire tippling class. Given the rancour and fury that often attends such rums by the social media commentariat, that’s no mean achievement.

Consider: there are nine separate micro-reviews on reddit for this thing, and on the RumRatings site, it has 437 ratings, of which more than 80% rate it 7 points or higher. Online magazines and aggregators like Distiller, Flaviar, Tastings, WineMag, Got Rum, Drink Hacker and Proof 66 have written extensively about its voluptuous charms. Even the blogosphere has always looked at it, always reviewed it, sometimes as one of their first rum reviews. Alex of the Rum Barrel, The Fat Rum Pirate, myself, the Rum Howler, Refined Vices, Ralfy, All At Sea, Rum Shop Boy, Rum Diaries Blog, Rum Gallery, Inu A Kena…all of us between 2006 and 2019 have, at some stage, tried the thing, and its popularity shows no sign of fading. If there was ever a gateway rum for the Latin style that isn’t from Panama or Cuba, then this is it (the Diplo may be another).

I think part of that is because there’s nothing excessive about it. Nor is there anything overly modest. It certainly evades the trap of turning into an over-sugared mess, or one where that’s all you taste, because the sweet, such as it is, is kept completely in the background. An August 2019 hydrometer test – mine – rates it as 36.96% ABV, which translates into 12g/L – not good, but hardly earth shaking when compared to other latin rums which have twice or three times that much, and many earlier reviews and tests actually showed none at all (this suggests either batch variation or an evolution in production philosophy); a Santa Teresa rep as recently as 2018 in an interview with Simon Johnson, stated flat out they don’t adulterate their rum. So, if you accept that, the only complaint that could be raised against it is that it really should be a few points stronger.

The nose is different from my admittedly fading tasting memories of ten years ago, when I first sampled it at a Liquorature get together in Calgary. Then I felt it had mostly standard South American aged rum components – vanilla, caramel, honey, light fruits, all rather low key. Now the blend presented otherwise: I was tasting glue, sugar cane sap, floor polish, varnish right up front, and I know that wasn’t any part of what I was smelling before. The 40% ABV still makes it too weak to mount an effective and aggressive nasal assault, and that is an issue they will have to address sooner or later – but at least, with some effort I also sensed very ripe apples, apricots, cherries in syrup, plus a dusting of cinnamon, molasses, caramel, and a little bite from oak, unsweetened dark chocolate and light orange peel.

It’s inoffensive in the extreme, there’s little to dislike here (except perhaps the strength), and for your average drinker, much to admire. The palate is quite good, if occasionally vague – light white fruits and toblerone, nougat, salted caramel ice cream, bon bons, sugar water, molasses, vanilla, dark chocolate, brown sugar and delicate spices – cinnamon and nutmeg. It’s darker in texture and thicker in taste than I recalled, but that’s all good, I think. It fails on the finish for the obvious reason, and the closing flavours that can be discerned are fleeting, short, wispy and vanish too quick.

It’s inoffensive in the extreme, there’s little to dislike here (except perhaps the strength), and for your average drinker, much to admire. The palate is quite good, if occasionally vague – light white fruits and toblerone, nougat, salted caramel ice cream, bon bons, sugar water, molasses, vanilla, dark chocolate, brown sugar and delicate spices – cinnamon and nutmeg. It’s darker in texture and thicker in taste than I recalled, but that’s all good, I think. It fails on the finish for the obvious reason, and the closing flavours that can be discerned are fleeting, short, wispy and vanish too quick.

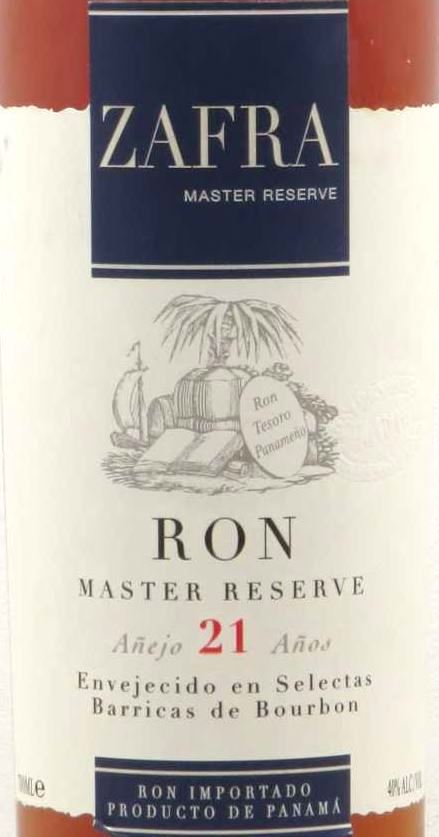

When rated against other rums of its type, the main competitors are the Zacapa, Zafra, Diplomatico Res Ex, the Kirk and Sweeney, or even the Millonario XO or Dictador. But I always found K&S to be too fixated on a particular “cinnamon-lite” profile; Diplo, Zafra and Zacapa were oversugared in comparison; and the Millonario XO was too excessive in both areas, as was Dictador with that coffee note it likes so much. Other producers of rums similar to the 1796 — solera or otherwise — are simply too small and lack market share, and impinge hardly at all in the larger popular consciousness (Don Q and Bacardi are different for other reasons).

But I believe that after all the years since 1996 when it was introduced (for Santa Tersa’s 200th Anniversary), there are good reasons it remains a fixture in the global rumscape and a perennial popular seller. As noted above, it can be found just about everywhere in a way that other Caribbean rums aren’t always; it’s extremely well known, and remains affordable to this day (around US$40 or so) — which is good for any average Joe who can’t always get or afford a New Jamaican or Barbadian or St. Lucian or Guyanese rum. Moreover, it just tastes good enough for most and can be used as a gateway rum for Latin/Spanish style rums in general and Venezuelan ones in particular. Of course, like most gateway rums, if you stick around long enough you’ll inevitably think one day that it’s too weak, too easy and too simple and move smartly along to the next milestone on the journey…but for anyone now starting and not looking to go anywhere, this is as lovely a Key Rum of the World as any on the list before it.

(#684)(78/100)

Other Notes (adapted from 2010 review)

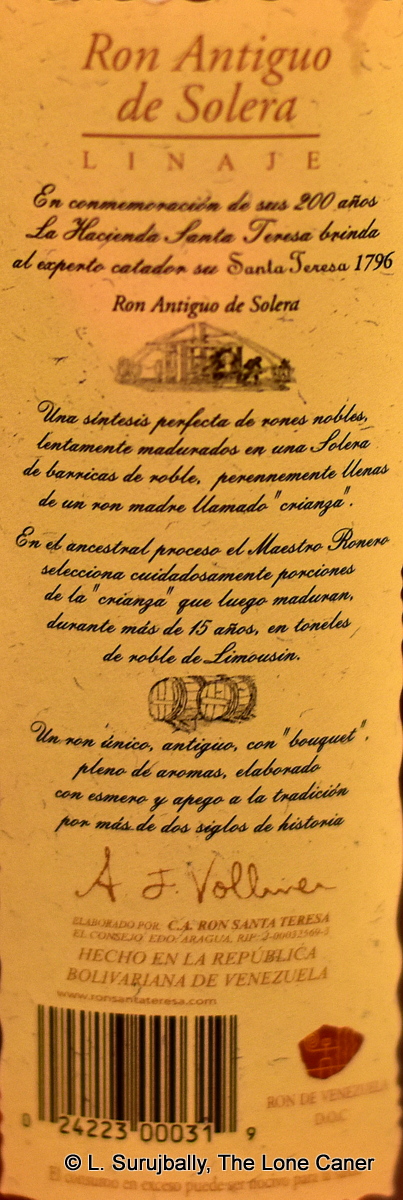

Santa Teresa distillery is located in Venezuela about an hour east of the capital, Caracas, on land given by the King of Spain to a favoured count in 1796. The estate ended up in the hands of a Gustavo Vollmer Rivas, who began making rum from sugar produced on nearby estates – owned by other Vollmerses – in the late 1800s. The Santa Teresa 1796 was produced in 1996 to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the estate land grant, and, produced by the solera method.

In the solera process, a succession of barrels is filled with rum over a series of equal aging intervals (usually a year). One container is filled for each interval. At the end of the interval after the last container is filled, the oldest container in the solera is tapped for part of its content (say, half), which is bottled. Then that container is refilled from the next oldest container, and that one in succession from the second-oldest, down to the youngest container, which is refilled with new product. This procedure is repeated at the end of each aging interval. The transferred product mixes with the older product in the next barrel.

No container is ever drained, so some of the earlier product always remains in each container. This remnant diminishes to a tiny level, but there can be significant traces of product much older than the average, depending on the transfer fraction. In theory traces of the very first product placed in the solera may be present even after 50 or 100 cycles. In the Santa Teresa, there are four levels of ageing. And the final solera is topped up with “Madre” spirit, which is a young blend deriving from both columnar and pot stills. Seems a bit complicated to me, but sherry makers have been doing it for centuries in Spain, so why not for rum? The downside is, of course, that there’s no way of saying how old it is since it is such a blend of older and younger rums. The marketing for the 1796 says the rum has components of between 4 to 35 years of age in it.

The rum was standard strength (40%), so it came as little surprise that the palate was very light, verging on airy – one burp and it was gone forever. Faintly sweet, smooth, warm, vaguely fruity, and again those minerally metallic notes could be sensed, reminding me of an empty tin can that once held peaches in syrup and had been left to dry. Further notes of vanilla, a single cherry and that was that, closing up shop with a finish that breathed once and died on the floor. No, really, that was it.

The rum was standard strength (40%), so it came as little surprise that the palate was very light, verging on airy – one burp and it was gone forever. Faintly sweet, smooth, warm, vaguely fruity, and again those minerally metallic notes could be sensed, reminding me of an empty tin can that once held peaches in syrup and had been left to dry. Further notes of vanilla, a single cherry and that was that, closing up shop with a finish that breathed once and died on the floor. No, really, that was it.

Next word: “Black”. Baby Rum Jesus help us. Long discredited as a way to classify rum, and if you are curious as to why, I refer you to

Next word: “Black”. Baby Rum Jesus help us. Long discredited as a way to classify rum, and if you are curious as to why, I refer you to

Rumaniacs Review #105 | 0678

Rumaniacs Review #105 | 0678 Nose – A combination of the

Nose – A combination of the  Rumaniacs Review #104 | 0677

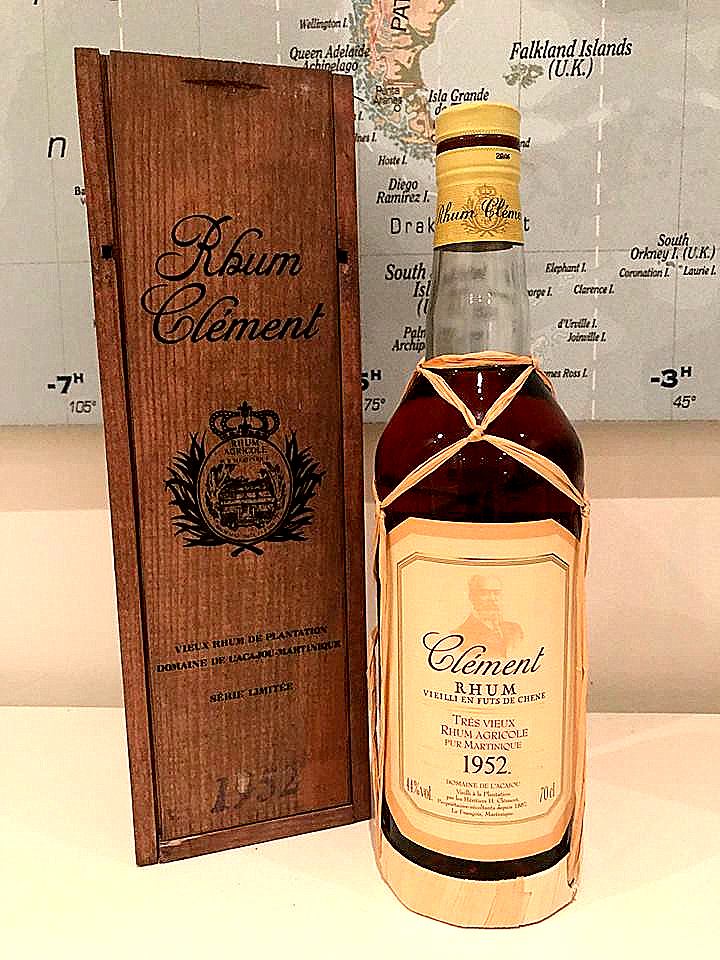

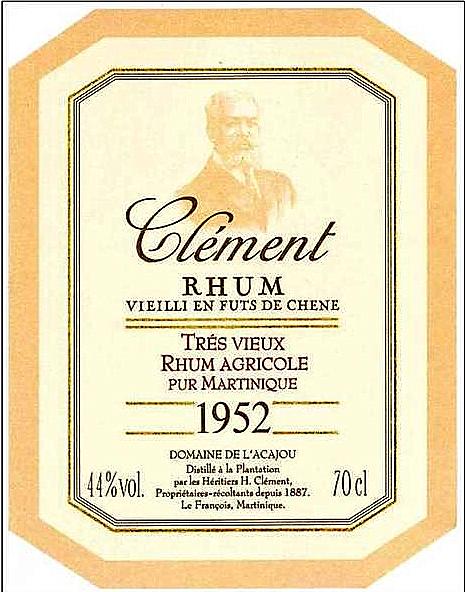

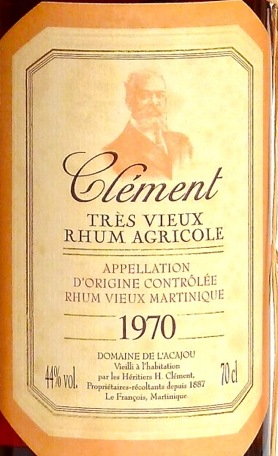

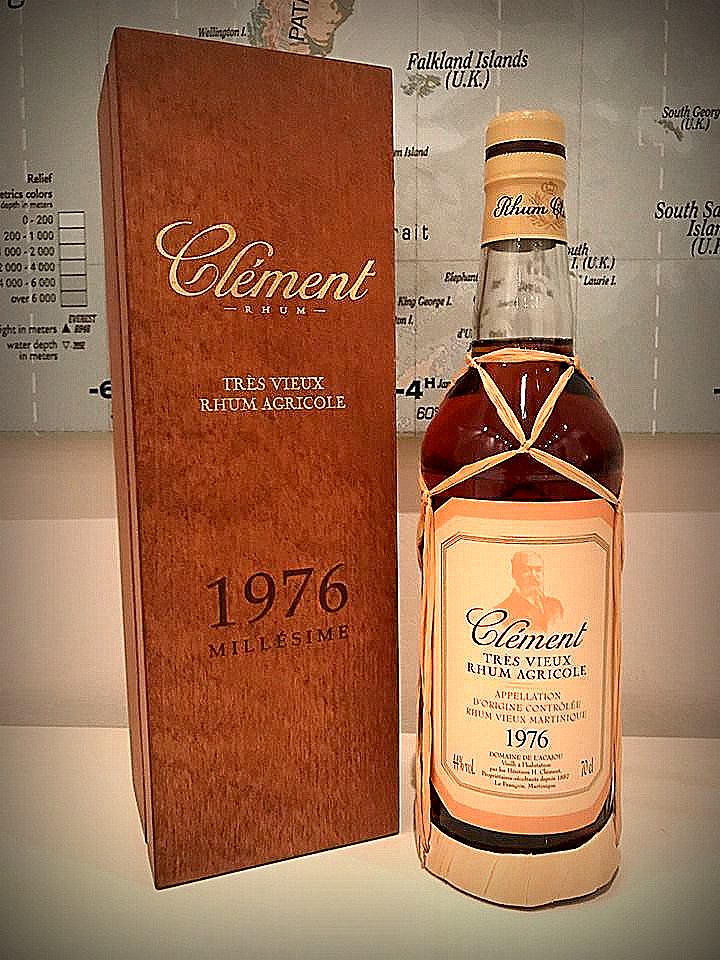

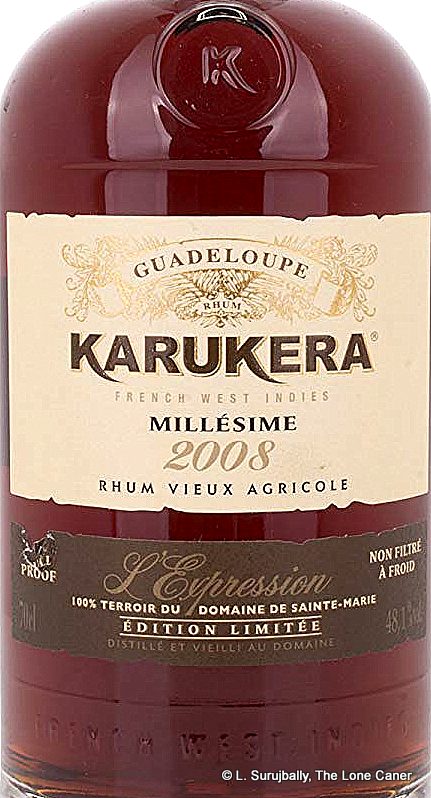

Rumaniacs Review #104 | 0677 Another peculiarity of the rhum is the “AOC” on the label. Since the AOC came into effect only in 1996, and even at its oldest this rhum was done ageing in 1991, how did that happen? Cyril told me it had been validated by the AOC after it was finalized, which makes sense (and probably applies to the 1976 edition as well), but then, was there a pre-1996 edition with one label and a post-1996 edition with another one? (the two different boxes it comes in suggests the possibility). Or, was the entire 1970 vintage aged to 1991, then held in inert containers (or bottled) and left to gather dust for some reason? Is either 1991 or 1985 even real? — after all, it’s entirely possible that the trio (of 1976, 1970 and 1952, whose labels are all alike) was released as a special millesime series in the late 1990s / early 2000s. Which brings us back to the original question – how old is the rhum?

Another peculiarity of the rhum is the “AOC” on the label. Since the AOC came into effect only in 1996, and even at its oldest this rhum was done ageing in 1991, how did that happen? Cyril told me it had been validated by the AOC after it was finalized, which makes sense (and probably applies to the 1976 edition as well), but then, was there a pre-1996 edition with one label and a post-1996 edition with another one? (the two different boxes it comes in suggests the possibility). Or, was the entire 1970 vintage aged to 1991, then held in inert containers (or bottled) and left to gather dust for some reason? Is either 1991 or 1985 even real? — after all, it’s entirely possible that the trio (of 1976, 1970 and 1952, whose labels are all alike) was released as a special millesime series in the late 1990s / early 2000s. Which brings us back to the original question – how old is the rhum? Rumaniacs Review #103 | 0676

Rumaniacs Review #103 | 0676

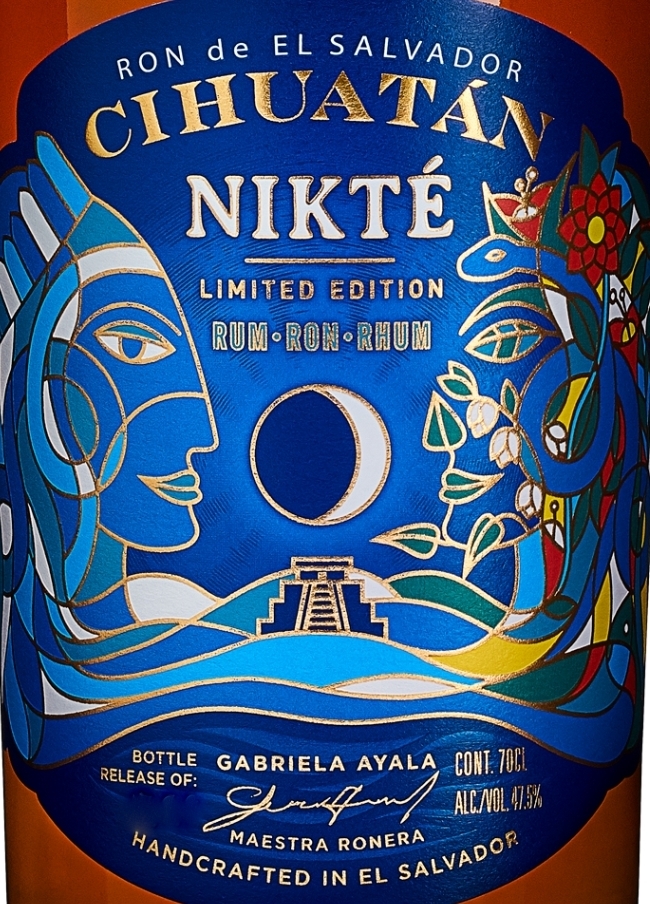

The name of the rum (or ron, if you will) relates back to the Mayan motif that has been part of the brand from the inception:

The name of the rum (or ron, if you will) relates back to the Mayan motif that has been part of the brand from the inception:

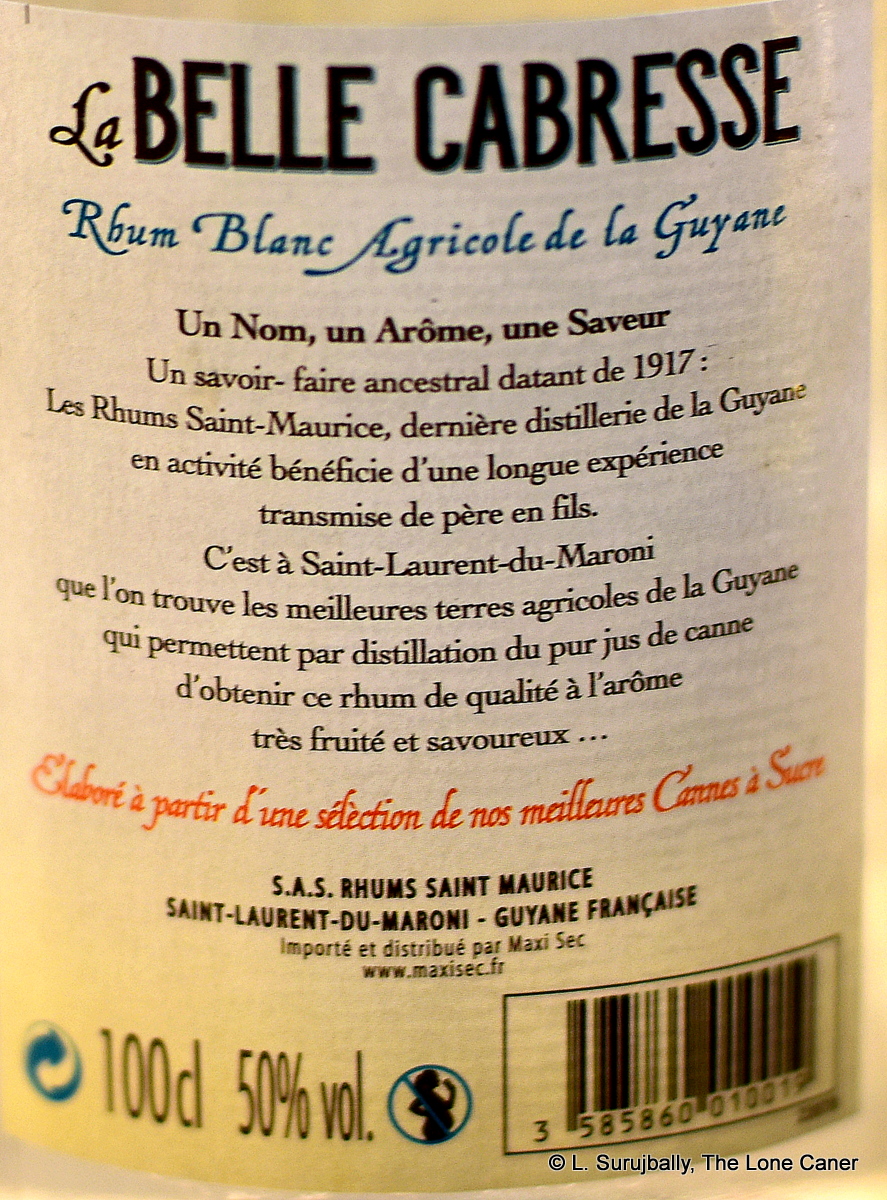

The rhum presents as warm rather than hot or sharp, so relatively tame to sniff, and this continues on to the palate. There a certain sweetness, light and clear, that is more pronounced in the initial sips, and the citrus notes are more noticeable, as are the brine and slight rottenness. What’s most distinct is the emergent strain of ouzo, of licorice (mostly absent from the nose until after it opens up a bit) … but fortunately this doesn’t take over, integrating reasonably well with tastes of clear bubble gum and strawberry soda pop that round out the crisp profile. Finish is medium long, dry, sweet, warm Guavas and white fruits and watery pears mingle with oranges and citrus peel and a slight dusting of salt, and that’s just about the whole story.

The rhum presents as warm rather than hot or sharp, so relatively tame to sniff, and this continues on to the palate. There a certain sweetness, light and clear, that is more pronounced in the initial sips, and the citrus notes are more noticeable, as are the brine and slight rottenness. What’s most distinct is the emergent strain of ouzo, of licorice (mostly absent from the nose until after it opens up a bit) … but fortunately this doesn’t take over, integrating reasonably well with tastes of clear bubble gum and strawberry soda pop that round out the crisp profile. Finish is medium long, dry, sweet, warm Guavas and white fruits and watery pears mingle with oranges and citrus peel and a slight dusting of salt, and that’s just about the whole story.

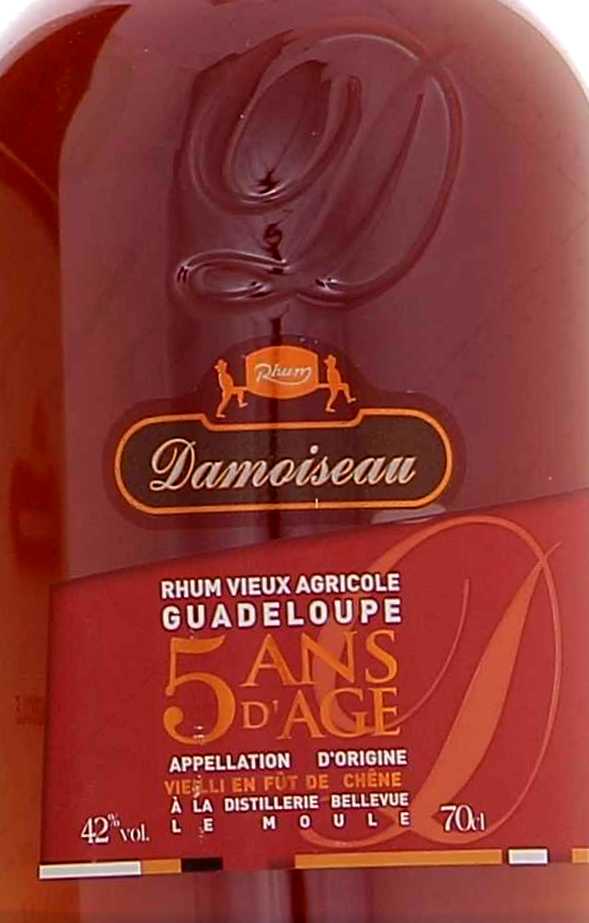

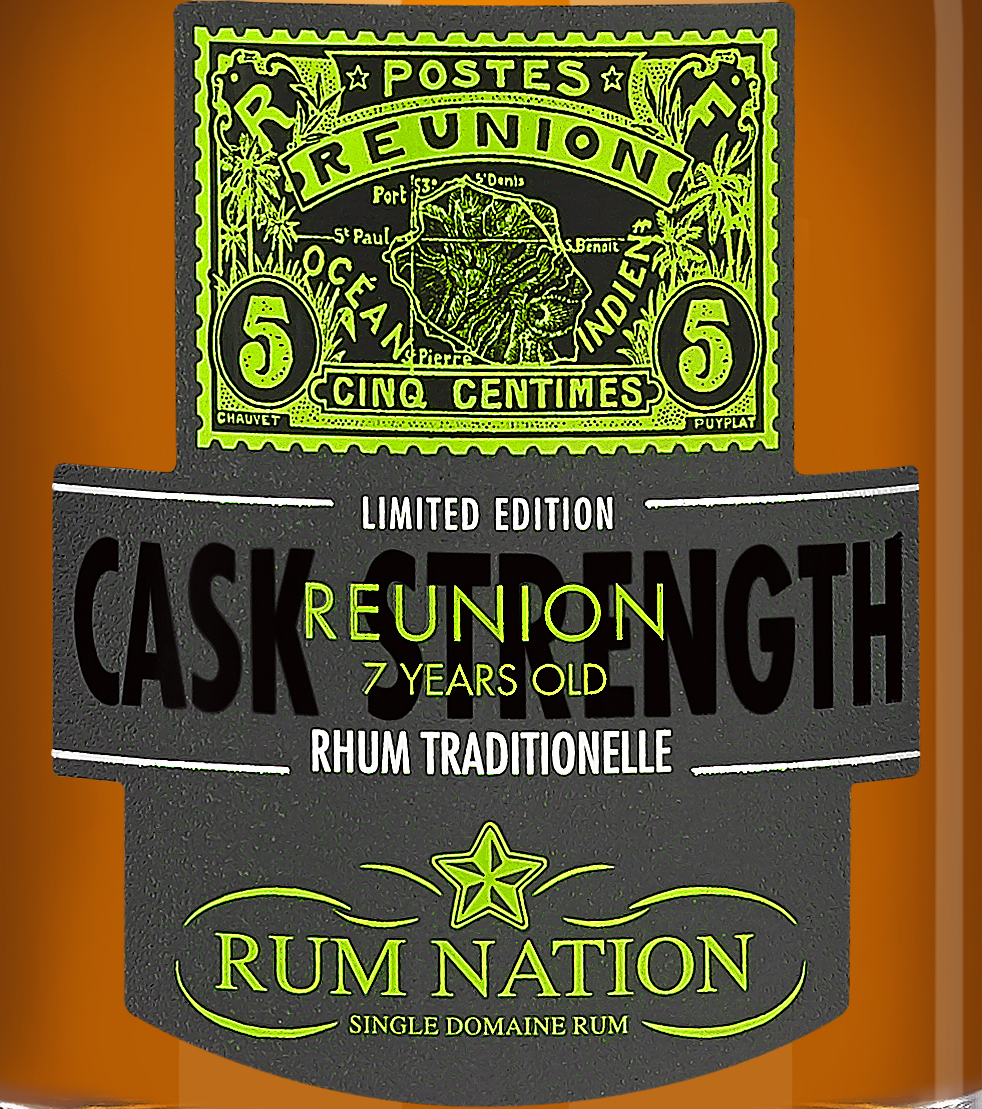

Unlike many aged agricoles that have run into my glass (and down my chin), I found this one to be quite sweet, and for all the solidity of the strength, also rather scrawny, a tad sharp. At least at the beginning, because once a drop of water was added and I chilled out a few minutes, it settled down and it tasted softer, earthier, muskier. Creamy salt butter on black bread, sour cream, yoghurt, and also fried bananas, pineapple, anise, lemon zest, cumin, raisins, green grapes, and a few more background fruits and florals, though these never come forward in any serious way. The finish is excellent, by the way – some vague molasses, burnt sugar, the creaminess of hummus and olive oil, caramel, flowers, apples and some tart notes of soursop and yellow mangoes and maybe a gooseberry or two. Nice.

Unlike many aged agricoles that have run into my glass (and down my chin), I found this one to be quite sweet, and for all the solidity of the strength, also rather scrawny, a tad sharp. At least at the beginning, because once a drop of water was added and I chilled out a few minutes, it settled down and it tasted softer, earthier, muskier. Creamy salt butter on black bread, sour cream, yoghurt, and also fried bananas, pineapple, anise, lemon zest, cumin, raisins, green grapes, and a few more background fruits and florals, though these never come forward in any serious way. The finish is excellent, by the way – some vague molasses, burnt sugar, the creaminess of hummus and olive oil, caramel, flowers, apples and some tart notes of soursop and yellow mangoes and maybe a gooseberry or two. Nice.

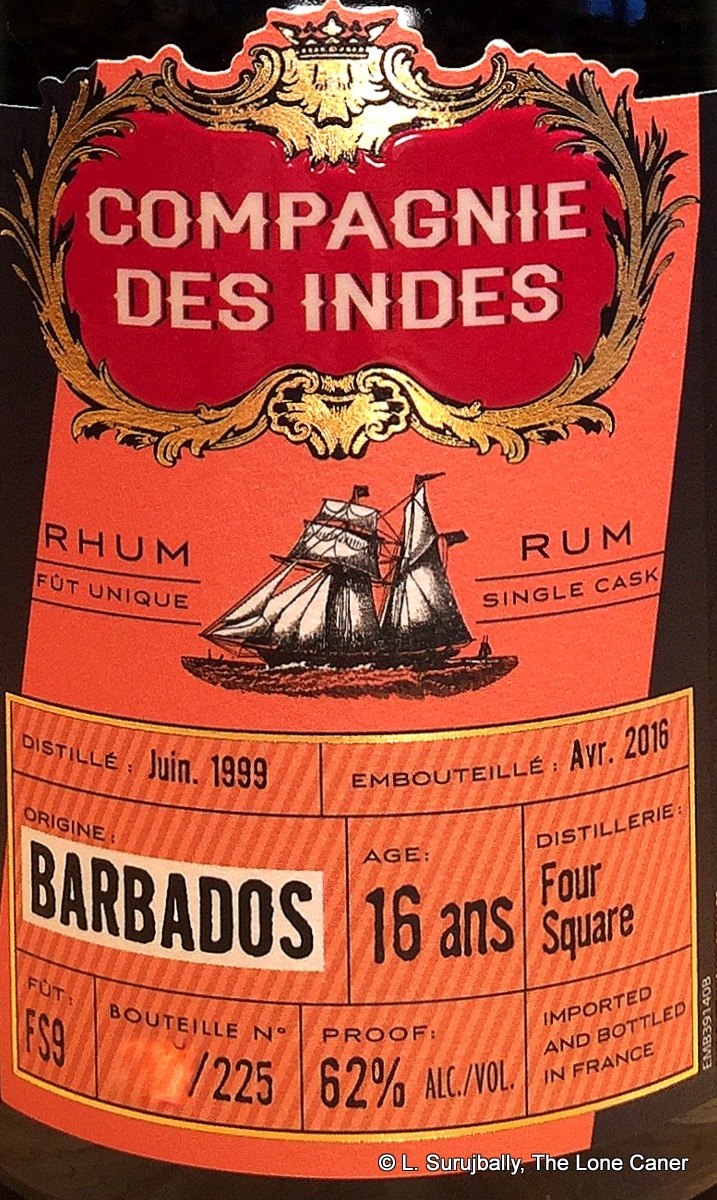

I don’t have any other observations to make, so let’s jump right in without further ado. Nose first – in a word, luscious. Although there are some salty hints to begin with, the overwhelming initial smells are of ripe black grapes, prunes, honey, and plums, with some flambeed bananas and brown sugar coming up right behind. The heat and bite of a 62% strength is very well controlled, and it presents as firm and strong without any bitchiness. After leaving it to open a few minutes, there are some fainter aromas of red/black olives, not too salty, as well as the bitter astringency of very strong black tea, and oak, mellowed by the softness of a musky caramel and vanilla, plus a sprinkling of herbs and maybe cinnamon. So quite a bit going on in there, and well worth taking one’s time with and not rushing to taste.

I don’t have any other observations to make, so let’s jump right in without further ado. Nose first – in a word, luscious. Although there are some salty hints to begin with, the overwhelming initial smells are of ripe black grapes, prunes, honey, and plums, with some flambeed bananas and brown sugar coming up right behind. The heat and bite of a 62% strength is very well controlled, and it presents as firm and strong without any bitchiness. After leaving it to open a few minutes, there are some fainter aromas of red/black olives, not too salty, as well as the bitter astringency of very strong black tea, and oak, mellowed by the softness of a musky caramel and vanilla, plus a sprinkling of herbs and maybe cinnamon. So quite a bit going on in there, and well worth taking one’s time with and not rushing to taste. We hear a lot about Damoiseau, HSE, La Favorite and Trois Rivieres on social media, while J.M. almost seems to fall into the second tier of famous names. Though not through any fault of its own – as far as I’m concerned they have every right to be included in the same breath as the others, and to many, it does.

We hear a lot about Damoiseau, HSE, La Favorite and Trois Rivieres on social media, while J.M. almost seems to fall into the second tier of famous names. Though not through any fault of its own – as far as I’m concerned they have every right to be included in the same breath as the others, and to many, it does.

Could a rum tropically aged for that long be anything but a success? Certainly the comments on the

Could a rum tropically aged for that long be anything but a success? Certainly the comments on the

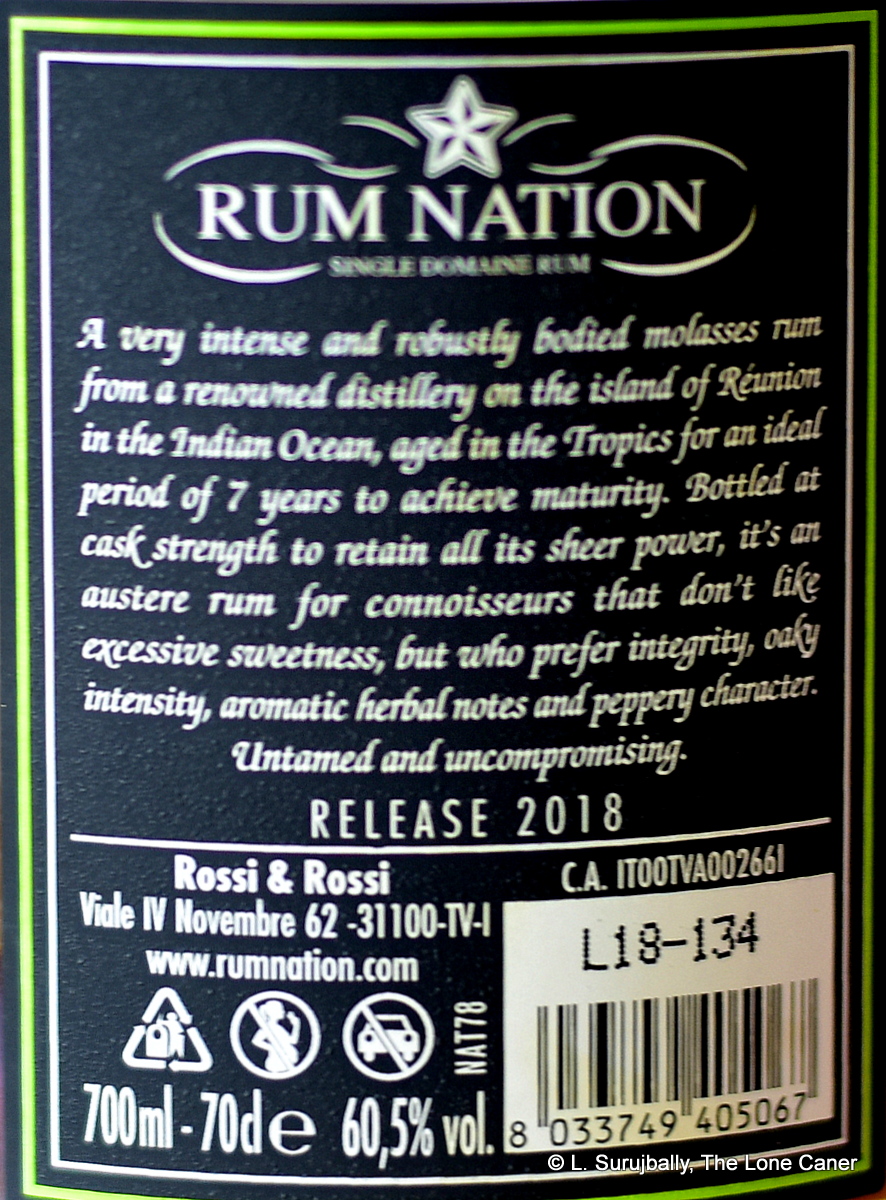

Some rums falter on the taste after opening up with a nose of uncommon quality – fortunately Rum Nation’s Réunion Cask Strength rum (to give it its full name) does not drop the ball. It’s sharp and crisp at the initial entry, mellowing out over time as one gets used to the fierce strength. It presents an interesting combination of fruitiness and muskiness and crispness, all at once – vanilla, lychee, apples, green grapes, mixing it up with ripe black cherries, yellow mangoes, lemongrass, leather, papaya; and behind all that is brine, olives, the earthy tang of a soya (easy on the vegetable soup), a twitch of wet cigarette tobacco (rather disgusting), bitter oak, and something vaguely medicinal. It’s something like a Hampden or WP, yet not — it’s too distinctively itself for that. It displays a musky tawniness, a very strong and sharp texture, with softer elements planing away the roughness of the initial attack. Somewhat over-oaked perhaps but somehow it all works really well, and the finish is similarly generous with what it provides — long and dry and spicy, with some caramel, stewed apples, green grapes, cider, balsamic vinegar, and a tannic bitterness of oak, barely contained (this may be the weakest point of the rum).

Some rums falter on the taste after opening up with a nose of uncommon quality – fortunately Rum Nation’s Réunion Cask Strength rum (to give it its full name) does not drop the ball. It’s sharp and crisp at the initial entry, mellowing out over time as one gets used to the fierce strength. It presents an interesting combination of fruitiness and muskiness and crispness, all at once – vanilla, lychee, apples, green grapes, mixing it up with ripe black cherries, yellow mangoes, lemongrass, leather, papaya; and behind all that is brine, olives, the earthy tang of a soya (easy on the vegetable soup), a twitch of wet cigarette tobacco (rather disgusting), bitter oak, and something vaguely medicinal. It’s something like a Hampden or WP, yet not — it’s too distinctively itself for that. It displays a musky tawniness, a very strong and sharp texture, with softer elements planing away the roughness of the initial attack. Somewhat over-oaked perhaps but somehow it all works really well, and the finish is similarly generous with what it provides — long and dry and spicy, with some caramel, stewed apples, green grapes, cider, balsamic vinegar, and a tannic bitterness of oak, barely contained (this may be the weakest point of the rum).