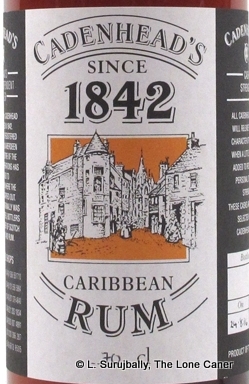

Cadenhead, in their various rum releases stretching back a hundred years or more, has three major rivers running into the great indie rum ocean, each of which has progressively less information than the one before it:

- The cask strength, single-barrel “Dated Distillation” series with a three- or four-letter identifier and lots of detail on source and age; I submit these are probably the best and rightly the most sought-after rums they release. The only question usually remaining when you get one, is what the letters stand for.

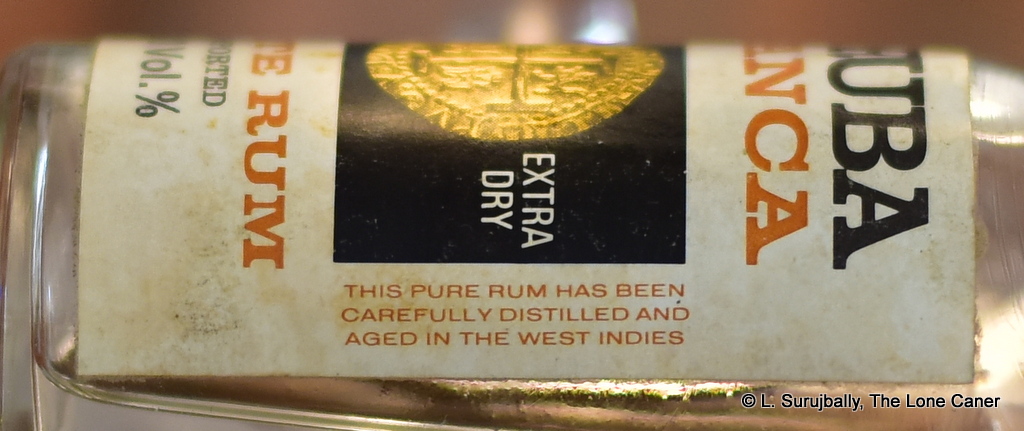

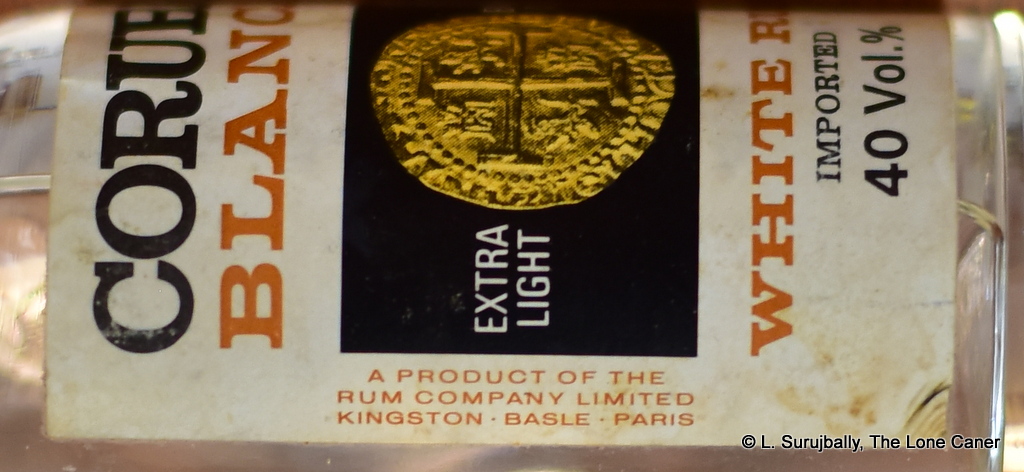

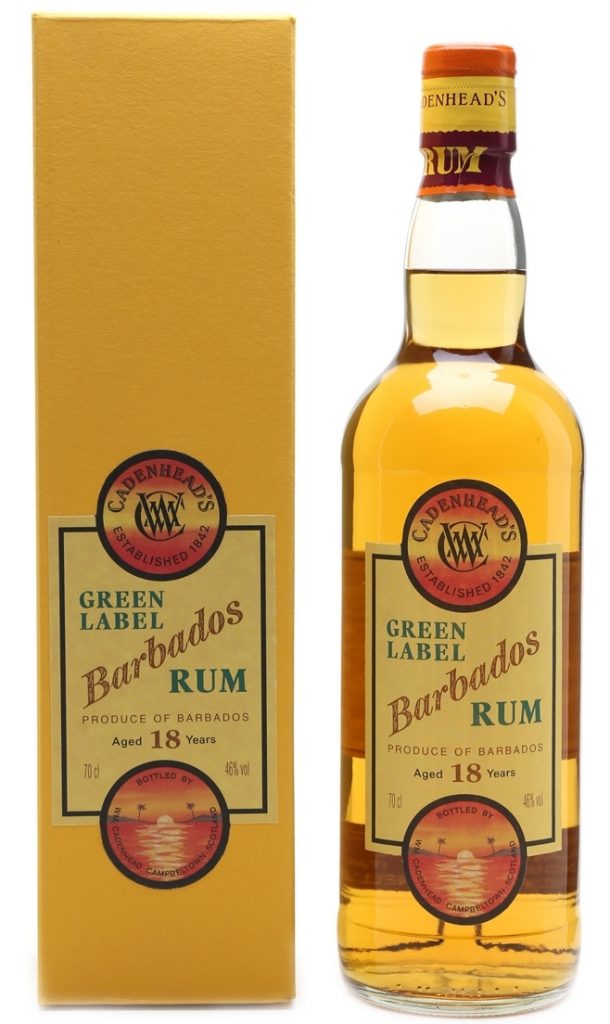

- The Green Label series; these are usually single-country blends, sometimes mashed together from multiple distilleries (or stills, or both), mostly from around the Caribbean and Central/South America (they’ve gone further afield of late). Here you get less detail than the DDs, mostly just the country, the age and the strength, which is always 46% ABV. I never really cared for their puke yellow labels with green and red accents, but now they’re green for real. Not much of an improvement, really.

- Classic Blended Rum; a blend of Caribbean rums, location never identified, age never stated (not on label or website), usually bottled at around 50% ABV. You takes your chances with these, and I’ve only ever had one, and quite liked it.

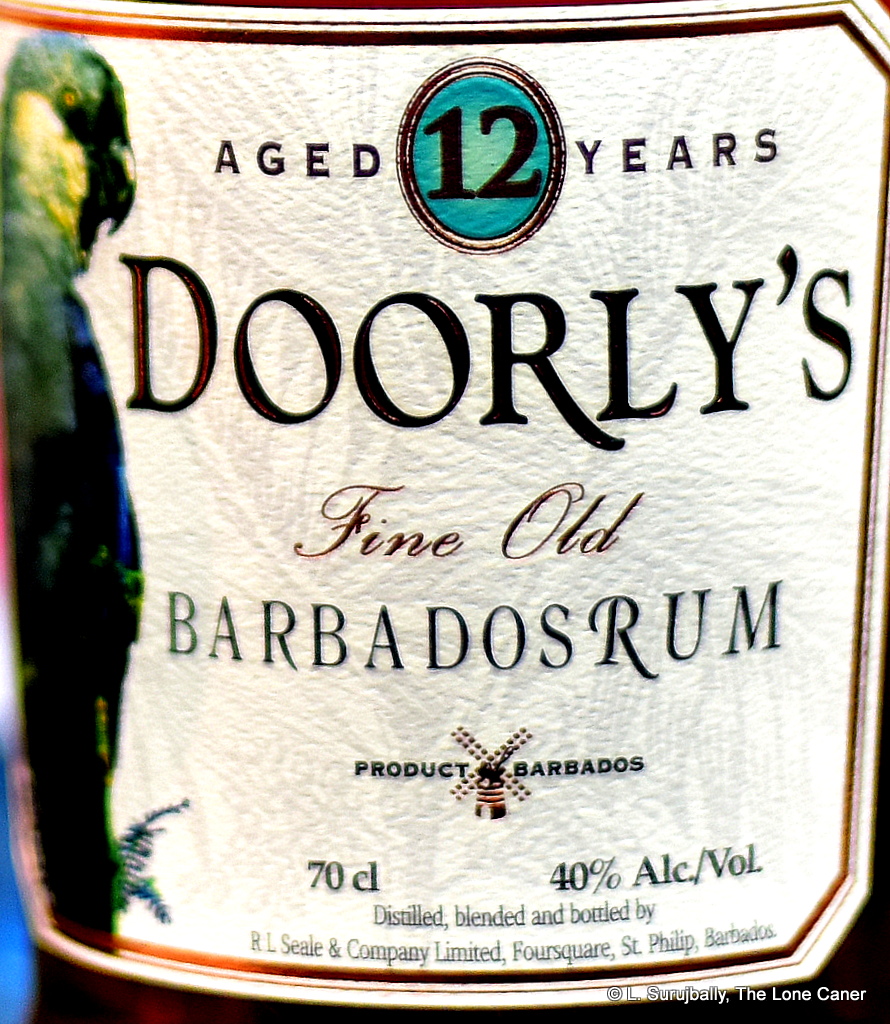

The subject of today’s review is a Green Label Barbados. This is not the first time that this series (which Cadenhead releases without schedule, rhyme or reason) has had a Barbadian rum in it: in fact, I had looked at a Barbados 10 year old back in 2017. There are at least seven rums that I know of in that series, not counting the full strength “Dated Distillation” collection, and I think they have an entrant from every distillery on the island between the two collections except St. Nicholas Abbey (which doesn’t export bulk). Most of the Greens are from WIRD or Mount Gay, while Foursquare is rather better represented of late in the DDs.

The subject of today’s review is a Green Label Barbados. This is not the first time that this series (which Cadenhead releases without schedule, rhyme or reason) has had a Barbadian rum in it: in fact, I had looked at a Barbados 10 year old back in 2017. There are at least seven rums that I know of in that series, not counting the full strength “Dated Distillation” collection, and I think they have an entrant from every distillery on the island between the two collections except St. Nicholas Abbey (which doesn’t export bulk). Most of the Greens are from WIRD or Mount Gay, while Foursquare is rather better represented of late in the DDs.

Which one is this, then? As far as I know, it’s a WIRD rum done in the Rockley style, based on these data points: Marco Freyr’s research, Marius Elder’s Rockley tasting based on research of his own, the year of distillation (1986 is a famous year for the Rockley style), and my own tasting – none of which is conclusive on its own, but which in aggregate are good enough for government work, and I’ll stand behind it until somebody issues the conclusive corrective.

I say it’s a Rockley style (see below for a historical recap), which is an opinion I came to after the tasting and before looking around for details, but what is it about its profile that bends my thinking that way? Well, let’s get started and I’ll try to explain.

Nose first: It’s both sharp and creamy at once, with clear veins of sweet red licorice, citrus, sprite and fanta running through a solid seam of caramel, toffee, white chocolate, almonds and a light latte. Letting it open up brings forth some light, clean floral scents, mint, sugar water, red currants and raisins, which the Little Caner grandly dismissed under with the brief title of “oldie fruity stuff.” (You can’t impress that boy, honestly).

The palate is interesting: it’s clean, yet also displaying some of the more solid notes which would suggest a pot still component; it retains the sharp and crisp tartness of unripe fruit – red currants, raspberries, strawberries, mangoes. Here the caramel bonbons and toffees take a back seat and touches of brine, pimentos and balsamic vinegar suggest themselves. Leaving it alone and then returning, additional notes of marzipan, green grapes and apples are noticeable, and also a rather more marked oak influence, though this does not, fortunately, overwhelm. The finish is dry, sweet and salt, with some medicinal iodine flashes, plus of course the oak, fruits and licorice, nothing too earthshaking here.

The rum as a whole is not unpleasant at all, and yes, it’s Rockley style — if you were to retry the SMWS R6.1 from 2002 (“Spice at the Races”) and then sample a few Foursquares and a MG XO, the difference is clear enough for there to be little doubt. Surprisingly, Marius felt the herbal and honey notes predominated and pushed the fruits to the back, while I thought the opposite. But he says and I inferred, that this is indeed a Rockley.

The rum as a whole is not unpleasant at all, and yes, it’s Rockley style — if you were to retry the SMWS R6.1 from 2002 (“Spice at the Races”) and then sample a few Foursquares and a MG XO, the difference is clear enough for there to be little doubt. Surprisingly, Marius felt the herbal and honey notes predominated and pushed the fruits to the back, while I thought the opposite. But he says and I inferred, that this is indeed a Rockley.

I think the extended maturation had something to do with how well it presented: even accounting for slower ageing in Scotland, eighteen years was sufficient to really enhance the distillate in a way that the older Samaroli WIRD 1986 released two years later somehow failed to do. It’s rare, unfortunately (we don’t know the outturn), but it’s come up for auction on whisky sites a few times and varies in price from £80-£120, which I think is pretty good deal for those who like Barbadian rums in general. This rum from Cadenhead is not a world beater, but it’s quite good on its own terms, and showcases an aspect of Barbados which is nice to try on occasion, if only for the variety.

(#845)(85/100)

The Rockley “Still”

(This section will not be updated, and has been transferred to its own post, here, to which all subsequent information will be added)

Many producers, commentators and reviewers, myself among them, refer to the pot still distillate from WIRR/WIRD as Rockley Still rum, and there are several who conflate this with “Blackrock”, which would include Cadenhead and Samaroli (but not 1423, who refer to their 2000 rum specifically as simply coming from a “pot still” at “West Indies” – Joshua Singh confirmed for me that it was indeed a “Blackrock style” rum).

They key write-ups that currently exist online are the articles that are based on the research published by Cedrik (in 2018) and Nick Arvanitis (in 2015) — adding to it now with some digging around on my own, here are some clarifications. None of it is new, but some re-posting is occasionally necessary for such articles to refresh and consolidate the facts.

“Blackrock” refers to WIRD as a whole, since the distillery is located next to an area of that name in NW Bridgetown (the capital), which was once a separate village. In the parlance, then, the WIRD distillery was sometimes referred to as “Blackrock” though this was never an official title – which didn’t stop Cadenhead and others from using it. There is no “Blackrock Still” and never has been.

Secondly, there is a “Rockley” pot still, which had possibly been acquired by a company called Batson’s (they were gathering the stills of closing operations for some reason) when the Rockley Distillery shuttered — Nick suggests it was transformed into a golf course in the late 1800s / early 1900s but provides no dates, and there is indeed a Rockley Resort and golf club in the SE of Bridgetown today. But I can’t find any reference to Batson’s online at all, nor the precise date when Rockley’s went belly-up — it is assumed to be at least a century ago. Nick writes that WIRD picked up a pot still from Batson’s between 1905 and 1920 (unlikely to be the one from Rockley), and it did work for a bit, but has not been operational since the 1950s.

This then leads to the other thread in this story which is the post-acquisition data provided by Alexandre Gabriel. In a FB video in 2018, summarized by Cedrik in his guest post on Single Cask, he noted that WIRD did indeed have a pot still from Batson’s acquired in 1936 which was inactive, as well as another pot still, the Rockley, which they got that same year, also long non-functional (in a 2021 FB post, WIRD claims a quote by John Dore’s president David Pym, that it’s the oldest rum pot still in the world, which I imagine would miff both DDL and Rivers Royale). According to their researches, it was apparently made by James Shears and Sons, a British coppersmith, active from 1785 to 1891. What this all means, though, is that there is no such thing as a rum made on the Rockley still in the post-1995 years of the current rum renaissance, and perhaps even earlier – the labels are all misleading, especially those of the much-vaunted year 1986.

The consensus these days is that yet a third pot still — acquired from Gregg’s Farms in the 1950s and which has remained operational to this day — provided the distillate for those rums in the last twenty years which bear the name Blackrock or Rockley. However, Cedrik adds that some of the older distillate might have come from the triple chamber Vulcan still which was variously stated as being inactive since the 1980s or 2000 (depending on the interview) and it was later confirmed that the most famous Rockley vintages from 1986 and 2000 were made with a combination of the Vulcan (used as a wash still) and the Gregg (as a spirit still).

Yet, as Cedrik so perceptively notes, even if there is no such thing as a Rockley-still rum, there is such a thing as a Rockley style. This has nothing to do with the erroneous association with a non-functional named still. What it is, is a flavour profile. It has notes of iodine, tar, petrol, brine, wax and heavier pot still accents, with honey and discernible esters. It is either loved or hated but very noticeable after one has gone through several Barbados rums. Marco Freyr often told me he could identify that profile by smell alone even if the bottler did not state it on the label, and I see no reason to doubt him.

As a final note, the actual, long non-functional Rockley still has long been sitting on the WIRD premises as a sort of historical artifact. In November 2021, it was noted they were shipping it off to a coppersmith in France for refurbishment, with view to making it useable again.

There are some older bottles in the review queue for products from what I term the “classic” era of the Swiss / German outfit of Secret Treasures, and it’s perhaps time to push them out the door in case some curious person ever wants to research them for an auction listing or something. Because what Secret Treasures are making now is completely different from what they did then, as I remarked in my brief company notes for

There are some older bottles in the review queue for products from what I term the “classic” era of the Swiss / German outfit of Secret Treasures, and it’s perhaps time to push them out the door in case some curious person ever wants to research them for an auction listing or something. Because what Secret Treasures are making now is completely different from what they did then, as I remarked in my brief company notes for

I do, on the other hand, like the taste. It’s warm and rich and the Enmore still profile – freshly sawn lumber, sawdust, pencil shavings – is clear. Also sour cream, eggnog, and bags of dried, dark fruits (raisins, prunes, dried plums) mix it up with a nice touch of sandalwood. It takes its own sweet time getting the the point and is a little discombobulated throughout, but I can’t argue with the stewed apples, dried orange peel, ripe red guavas and licorice – it’s nice. The finish is quite solid, if unexceptional: it lasts a fair bit, and you’re left with closing notes of licorice, oak chips, vanilla, dried fruit and black cake.

I do, on the other hand, like the taste. It’s warm and rich and the Enmore still profile – freshly sawn lumber, sawdust, pencil shavings – is clear. Also sour cream, eggnog, and bags of dried, dark fruits (raisins, prunes, dried plums) mix it up with a nice touch of sandalwood. It takes its own sweet time getting the the point and is a little discombobulated throughout, but I can’t argue with the stewed apples, dried orange peel, ripe red guavas and licorice – it’s nice. The finish is quite solid, if unexceptional: it lasts a fair bit, and you’re left with closing notes of licorice, oak chips, vanilla, dried fruit and black cake.

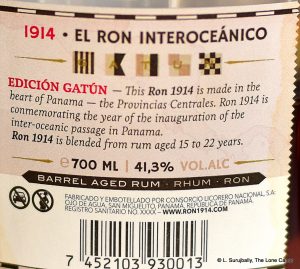

Tasting notes. The nose is nice. At under 50% not too much sharpness, just a good solid heat, redolent of soda, fanta, coca cola and strawberries. There’s a trace of coffee and rye bread, and also a nice fruity background of apples, green grapes, yellow mangoes and kiwi fruit. It develops well and no fault can found with the balance among these disparate elements.

Tasting notes. The nose is nice. At under 50% not too much sharpness, just a good solid heat, redolent of soda, fanta, coca cola and strawberries. There’s a trace of coffee and rye bread, and also a nice fruity background of apples, green grapes, yellow mangoes and kiwi fruit. It develops well and no fault can found with the balance among these disparate elements.

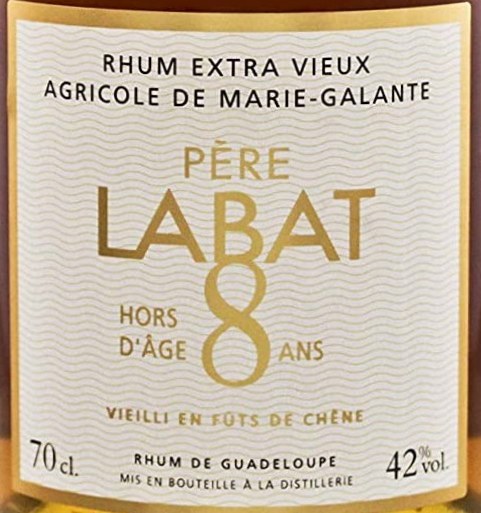

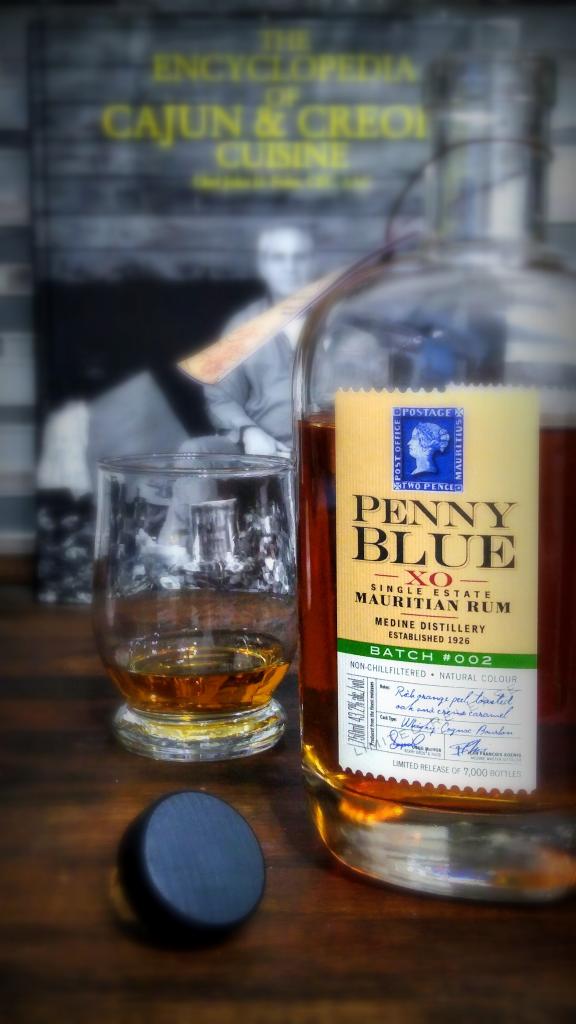

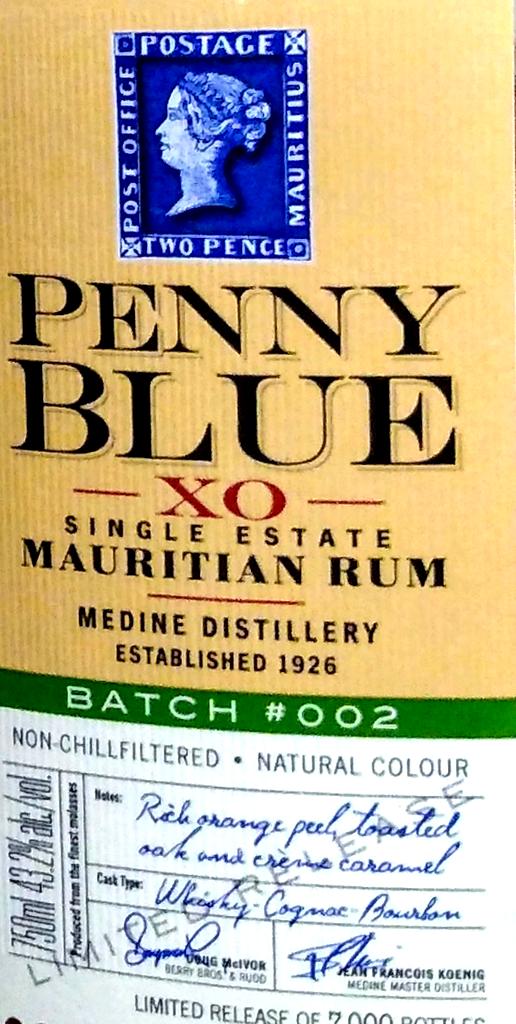

Does this multiple wood ageing result in anything worth drinking? Yes it does – the extra year seems to have had an interesting and salutary effect on the profile – though at 42.7% it remains as easy and soft as its siblings. The nose, for example, is a nice step up: cardboard, musty paper, some dunder of spoiled bananas skins, plus strawberries and soft pineapple or two and brine (which, I swear, made me think of Hawaiian pizza). Caramel and bitter dark chocolate round things off. It’s a relatively easy sniff, inoffensive yet solid.

Does this multiple wood ageing result in anything worth drinking? Yes it does – the extra year seems to have had an interesting and salutary effect on the profile – though at 42.7% it remains as easy and soft as its siblings. The nose, for example, is a nice step up: cardboard, musty paper, some dunder of spoiled bananas skins, plus strawberries and soft pineapple or two and brine (which, I swear, made me think of Hawaiian pizza). Caramel and bitter dark chocolate round things off. It’s a relatively easy sniff, inoffensive yet solid.

But a gent called

But a gent called

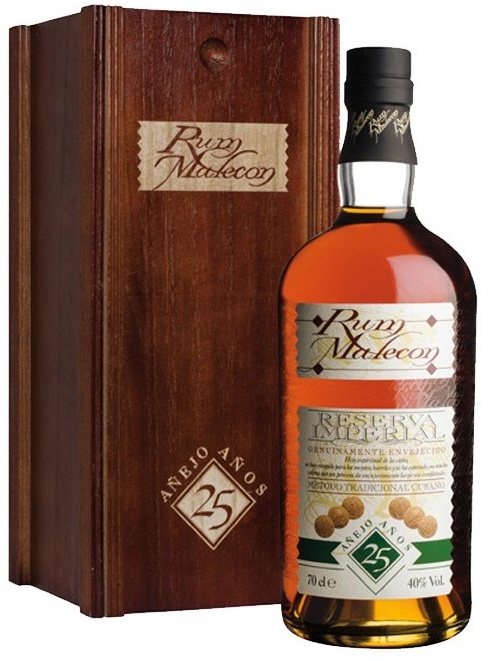

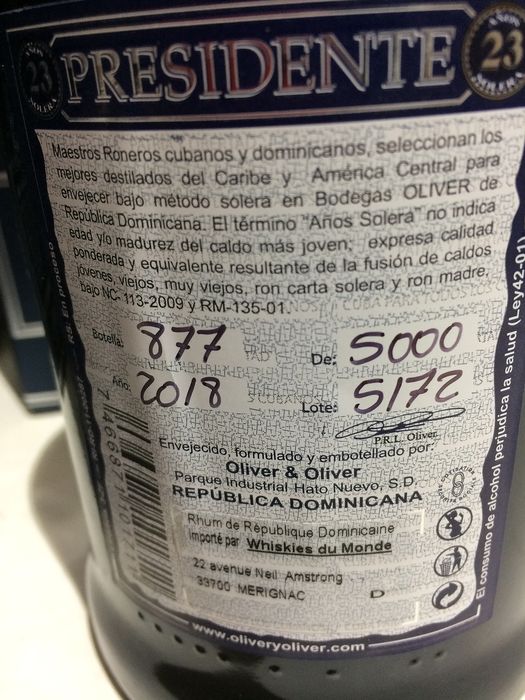

We’ve been here before. We’ve tried a rum with this name, researched its background, been baffled by its opaqueness, made our displeasure known, then yawned and shook our heads and moved on. And still the issues that that one raised, remain. The Malecon Reserva Imperial 25 year old suffers from many of the same defects of its

We’ve been here before. We’ve tried a rum with this name, researched its background, been baffled by its opaqueness, made our displeasure known, then yawned and shook our heads and moved on. And still the issues that that one raised, remain. The Malecon Reserva Imperial 25 year old suffers from many of the same defects of its  The palate is similarly soft and similarly straightforward. It’s got more chocolate milk and and perhaps a touch of coffee grounds. A smidgen, barely a smidgen of oak and citrus, a sly taste of tangerines; it’s not very sweet (which is a plus) and sports some brine and Turkish olives and a touch of slight bitterness, which I’m going be generous and say is an oak influence that saves it from being just blah. Finish is okay I guess. Gone too quickly of course, no surprise at 40% ABV and leaving at best the sense of some black tea with too much condensed milk in it, that doesn’t entirely hide the fact that it’s too bitter.

The palate is similarly soft and similarly straightforward. It’s got more chocolate milk and and perhaps a touch of coffee grounds. A smidgen, barely a smidgen of oak and citrus, a sly taste of tangerines; it’s not very sweet (which is a plus) and sports some brine and Turkish olives and a touch of slight bitterness, which I’m going be generous and say is an oak influence that saves it from being just blah. Finish is okay I guess. Gone too quickly of course, no surprise at 40% ABV and leaving at best the sense of some black tea with too much condensed milk in it, that doesn’t entirely hide the fact that it’s too bitter.

It gets no better when tasted. It’s very darkly sweet, liqueur-like, giving up flavours of prunes and stewed apples (again); dates; peaches in syrup, yes, more syrup, vanilla and a touch of cocoa. Honey, Cointreau, and both cloying and wispy at the same time, with a last gasp of caramel and toffee. The finish is thankfully short, sweet, thin, faint, nothing new except maybe some creme brulee. It’s a rum that, in spite of its big number and heroic Jose Marti visage screams neither quality or complexity. Mostly it yawns “boring!”

It gets no better when tasted. It’s very darkly sweet, liqueur-like, giving up flavours of prunes and stewed apples (again); dates; peaches in syrup, yes, more syrup, vanilla and a touch of cocoa. Honey, Cointreau, and both cloying and wispy at the same time, with a last gasp of caramel and toffee. The finish is thankfully short, sweet, thin, faint, nothing new except maybe some creme brulee. It’s a rum that, in spite of its big number and heroic Jose Marti visage screams neither quality or complexity. Mostly it yawns “boring!”

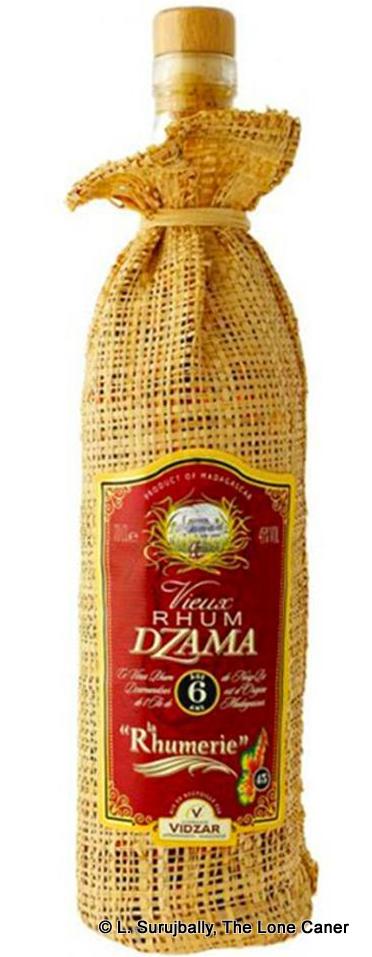

The palate was thick, rich and sweet, even in comparison the the 3YO which showed no modesty with such aspects itself but while stronger, had also been paradoxically easier. Here we were regaled with bananas, cherries in syrup, brown sugar, and a sort of smorgasbord of fruitiness – some tart, some just soft and mushy – and creaminess of greek yogurt sprinkled with cinnamon and cloves. Disappointingly, the finish did nothing much except lock the door and walk off, throwing a few notes of cloves, sugar, cherries, peaches and syrup behind. Not a stellar finish after the intriguing beginning.

The palate was thick, rich and sweet, even in comparison the the 3YO which showed no modesty with such aspects itself but while stronger, had also been paradoxically easier. Here we were regaled with bananas, cherries in syrup, brown sugar, and a sort of smorgasbord of fruitiness – some tart, some just soft and mushy – and creaminess of greek yogurt sprinkled with cinnamon and cloves. Disappointingly, the finish did nothing much except lock the door and walk off, throwing a few notes of cloves, sugar, cherries, peaches and syrup behind. Not a stellar finish after the intriguing beginning.

Or so the story-teller in me supposes. Because all jokes and anecdotes aside, what this is, is a rum made to order.

Or so the story-teller in me supposes. Because all jokes and anecdotes aside, what this is, is a rum made to order.

Rumaniacs Review #122 | 0785

Rumaniacs Review #122 | 0785