It’s been some time since a current production Cuban rum not made by a third party crossed my path. Among those was the Santiago de Cuba 12 YO, which, at the time, I enjoyed a lot, and made me anxious to see how older versions from the Cuba Rum Corporation’s stable would work out. So when the 25 YO became available, you’d better believe I snapped it up, and ran it past a bunch of other Latin rums: a Don Q, the Diplomatico “Distillery Collection” No. 1 and No. 2 rums, a Zafra 21 and just because I could, a Kirk & Sweeney 18 YO.

The Cuba Rum Corporation is the state owned organization located in the southern town of Santiago de Cuba, and is the oldest factory in the country, being established in 1862 by the Bacardi family who were expropriated after the Cuban Revolution in 1960. The CRC kept up the tradition of making light column-still Cuban rum and nowadays make the Ron Caney, Varadero and Santiago de Cuba lines, the last of which consists of an underproof blanca and sub-5YO anejo, and 40% 12 YO, 20 YO and this 25 YO. The 25 YO is their halo product, introduced in 2005 in honour of the 490th anniversary of the city of Santiago de Cuba’s founding and is lavish bottle and box presentation underscores the point (if the price doesn’t already do that).

Could a rum tropically aged for that long be anything but a success? Certainly the comments on the crowd-sourced Rum Ratings site (all thirteen of them, ten of which rated it 9 or 10 points out of ten) suggest that it is nothing short of spectacular.

Could a rum tropically aged for that long be anything but a success? Certainly the comments on the crowd-sourced Rum Ratings site (all thirteen of them, ten of which rated it 9 or 10 points out of ten) suggest that it is nothing short of spectacular.

The nose was certainly good – it smelled richly of leather, mint, creme brulee, caramel, raisins, cherries, and vanilla. The aromas were soft, yet with something of an edge to them as well, a bit of oak and tar, some citrus peel and lemon juice (just a little), plus a whiff of charcoal and smoke that was not displeasing. Even at 40% (and I wish it was more) it was enormously satisfying, if unavoidably light. Good thing I tried it early in the session – had it come after a bunch of cask strength hooligans, I might have passed it by with indifference and without further comment.

The challenge came as it was tasted, because this is where standard strength 40% ABV usually falls flat and betrays itself as it disappears into a wispy nothingness, but no, somehow the 25 year old got up and kept running, in spite of that light profile. The mouthfeel was silky, quite smooth and easy, tasting of cinnamon, aromatic tobacco, a bit of coffee. Then came citrus, nuts, some very faint fruits – raisins again, ripe red grapes, kiwi fruits, sapodilla, yellow mangoes – that was impressive, sure, it’s just that one had to reach and strain and really pay attention to tease out those notes…which may be defeating the purpose of a leisurely dram sipped as the sun goes down somewhere tropical. Unsurprisingly the finish failed (for me at any rate – your mileage may, of course, vary): it puffed some leather and light fruits and cherries, added a hint of cocoa and vanilla, and then it was over.

The Santiago de Cuba brand was supposedly Castro’s favourite, which may be why the Isla del Tesoro presentation quality rum retails for a cool £475 on the Whisky Exchange and this one retails for around £300 or so. Personally I find it a rum that needs strengthening. The tastes and smells are great – the nose, as noted, was really quite outstanding – the balance nicely handled, with sweet and tart and acidity and muskiness in a delicate harmony, and that they did it without any adulteration goes without saying. It would, six years ago, have scored as good or better than the 12 year old (86 points, to save you looking).

But these days I can’t quite endorse it as enthusiastically as before even if it is a quarter of a century old, and so must give it the score I do…but with the usual caveat: if you love Cubans and prefer softer, lighter, standard proofed rums, then add five points to my score to see where it should rank for you. Even if you don’t, rest assured that this is one of the better Cuban rums out there, tasty, languorous, complex, well-balanced….and too light. It’s undone – and only in the eyes of this one reviewer – by being made for the palates of yesteryear, instead of beefing itself up (even incrementally) to something more for those who, like me, prefer something more forceful and distinct.

(#641)(82/100)

Other notes

Pierre-Olivier Coté’s informative 2015 review on Quebec Rum noted the outturn as 8,000 botles. One wonders whether this is a one-off, or an annual release level.

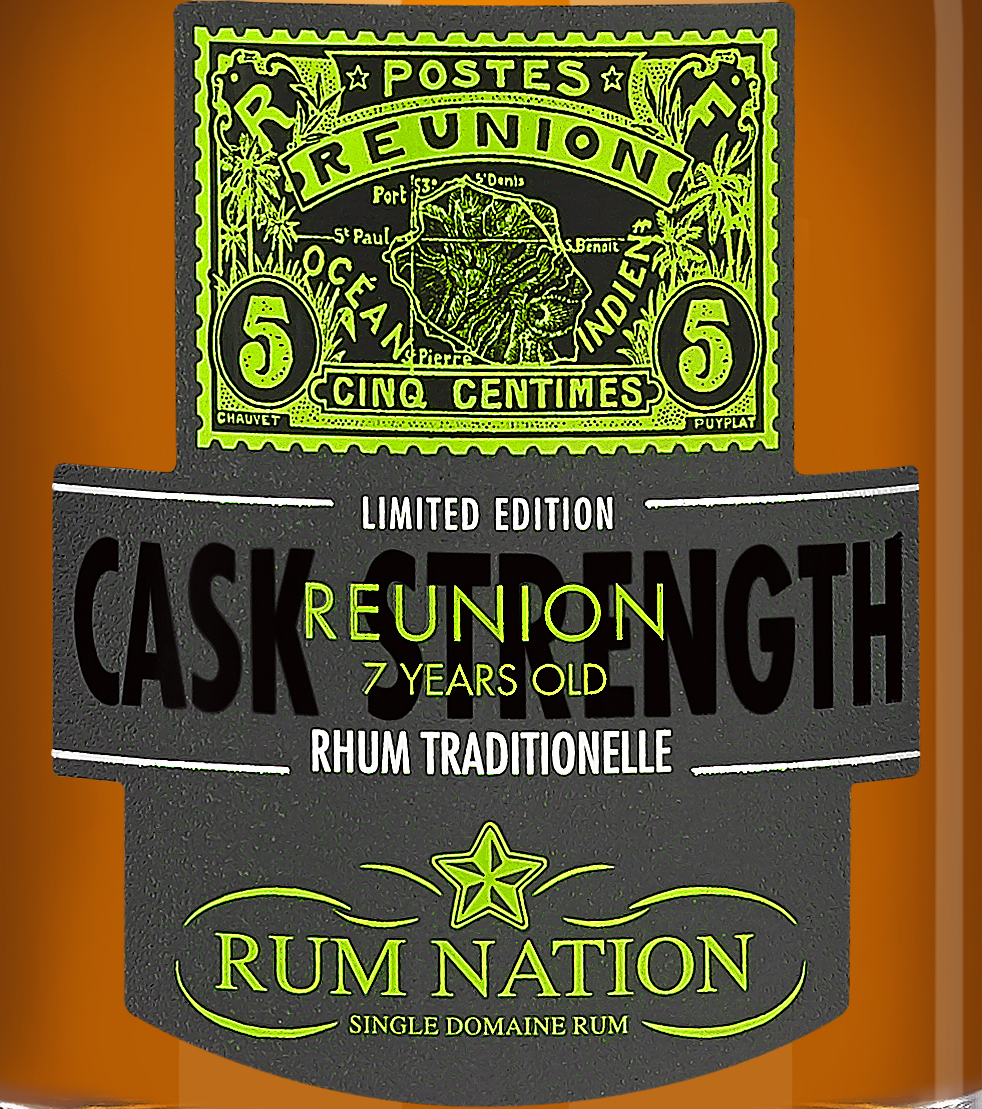

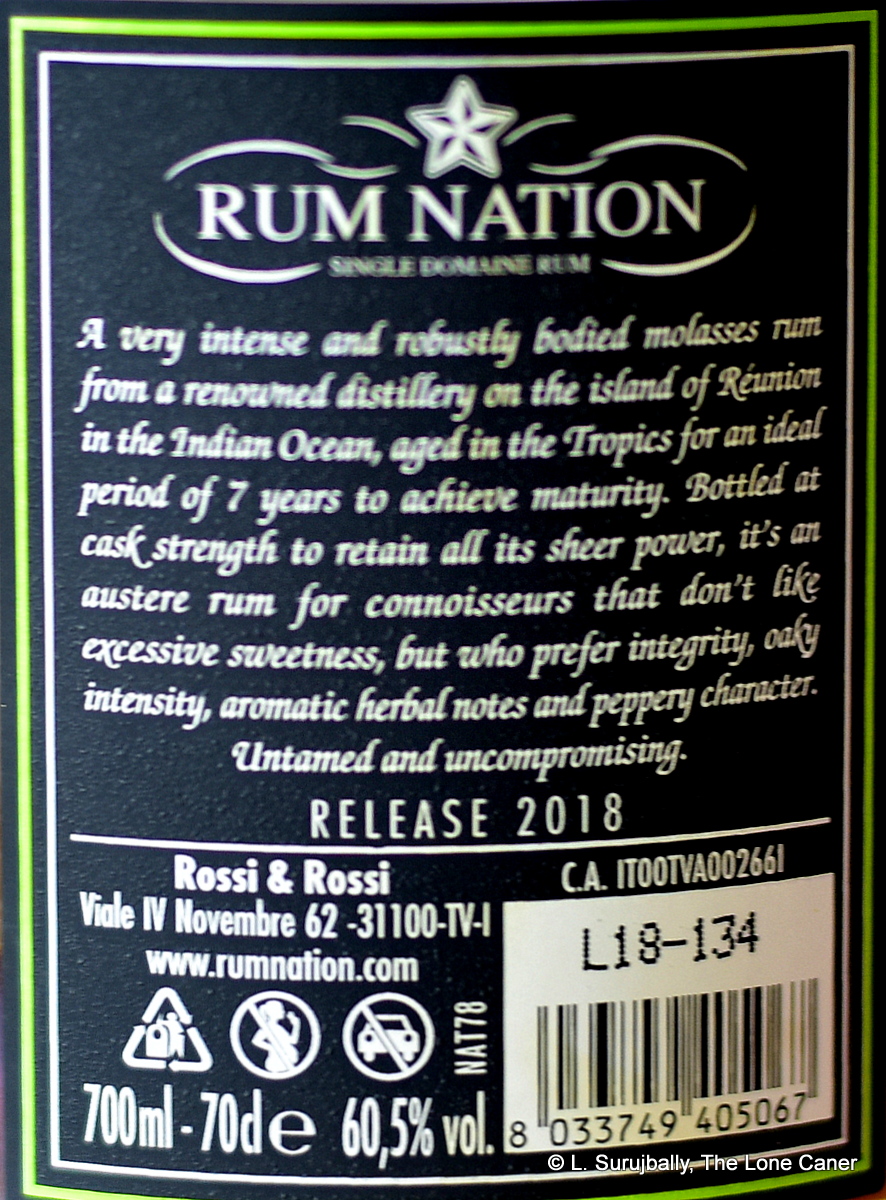

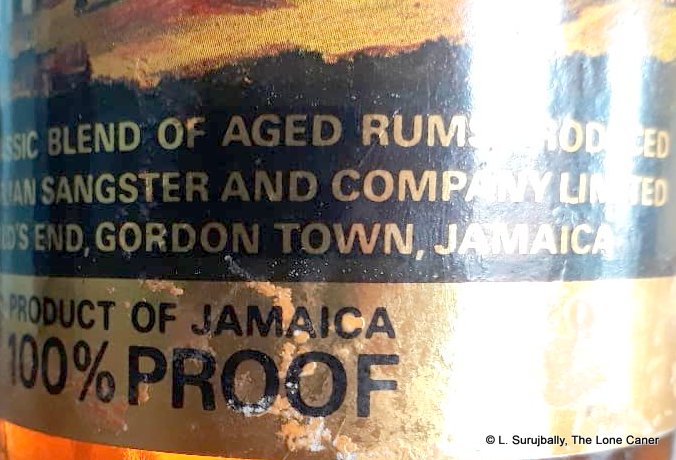

Some rums falter on the taste after opening up with a nose of uncommon quality – fortunately Rum Nation’s Réunion Cask Strength rum (to give it its full name) does not drop the ball. It’s sharp and crisp at the initial entry, mellowing out over time as one gets used to the fierce strength. It presents an interesting combination of fruitiness and muskiness and crispness, all at once – vanilla, lychee, apples, green grapes, mixing it up with ripe black cherries, yellow mangoes, lemongrass, leather, papaya; and behind all that is brine, olives, the earthy tang of a soya (easy on the vegetable soup), a twitch of wet cigarette tobacco (rather disgusting), bitter oak, and something vaguely medicinal. It’s something like a Hampden or WP, yet not — it’s too distinctively itself for that. It displays a musky tawniness, a very strong and sharp texture, with softer elements planing away the roughness of the initial attack. Somewhat over-oaked perhaps but somehow it all works really well, and the finish is similarly generous with what it provides — long and dry and spicy, with some caramel, stewed apples, green grapes, cider, balsamic vinegar, and a tannic bitterness of oak, barely contained (this may be the weakest point of the rum).

Some rums falter on the taste after opening up with a nose of uncommon quality – fortunately Rum Nation’s Réunion Cask Strength rum (to give it its full name) does not drop the ball. It’s sharp and crisp at the initial entry, mellowing out over time as one gets used to the fierce strength. It presents an interesting combination of fruitiness and muskiness and crispness, all at once – vanilla, lychee, apples, green grapes, mixing it up with ripe black cherries, yellow mangoes, lemongrass, leather, papaya; and behind all that is brine, olives, the earthy tang of a soya (easy on the vegetable soup), a twitch of wet cigarette tobacco (rather disgusting), bitter oak, and something vaguely medicinal. It’s something like a Hampden or WP, yet not — it’s too distinctively itself for that. It displays a musky tawniness, a very strong and sharp texture, with softer elements planing away the roughness of the initial attack. Somewhat over-oaked perhaps but somehow it all works really well, and the finish is similarly generous with what it provides — long and dry and spicy, with some caramel, stewed apples, green grapes, cider, balsamic vinegar, and a tannic bitterness of oak, barely contained (this may be the weakest point of the rum).

2014 was both too late and a bad year for those who started to wake up and realize that Velier’s Demerara rums were something special, because by then the positive reviews had started coming out the door, the prices began their inexorable rise, and, though we did not know it, it would mark the last issuance of any

2014 was both too late and a bad year for those who started to wake up and realize that Velier’s Demerara rums were something special, because by then the positive reviews had started coming out the door, the prices began their inexorable rise, and, though we did not know it, it would mark the last issuance of any

And why shouldn’t they? It’s a fifteen year old rum issued at a relatively affordable price, and is widely available, has been around for decades and has decent flavour chops for those who don’t have the interest or the coin for the limited edition independents.

And why shouldn’t they? It’s a fifteen year old rum issued at a relatively affordable price, and is widely available, has been around for decades and has decent flavour chops for those who don’t have the interest or the coin for the limited edition independents.

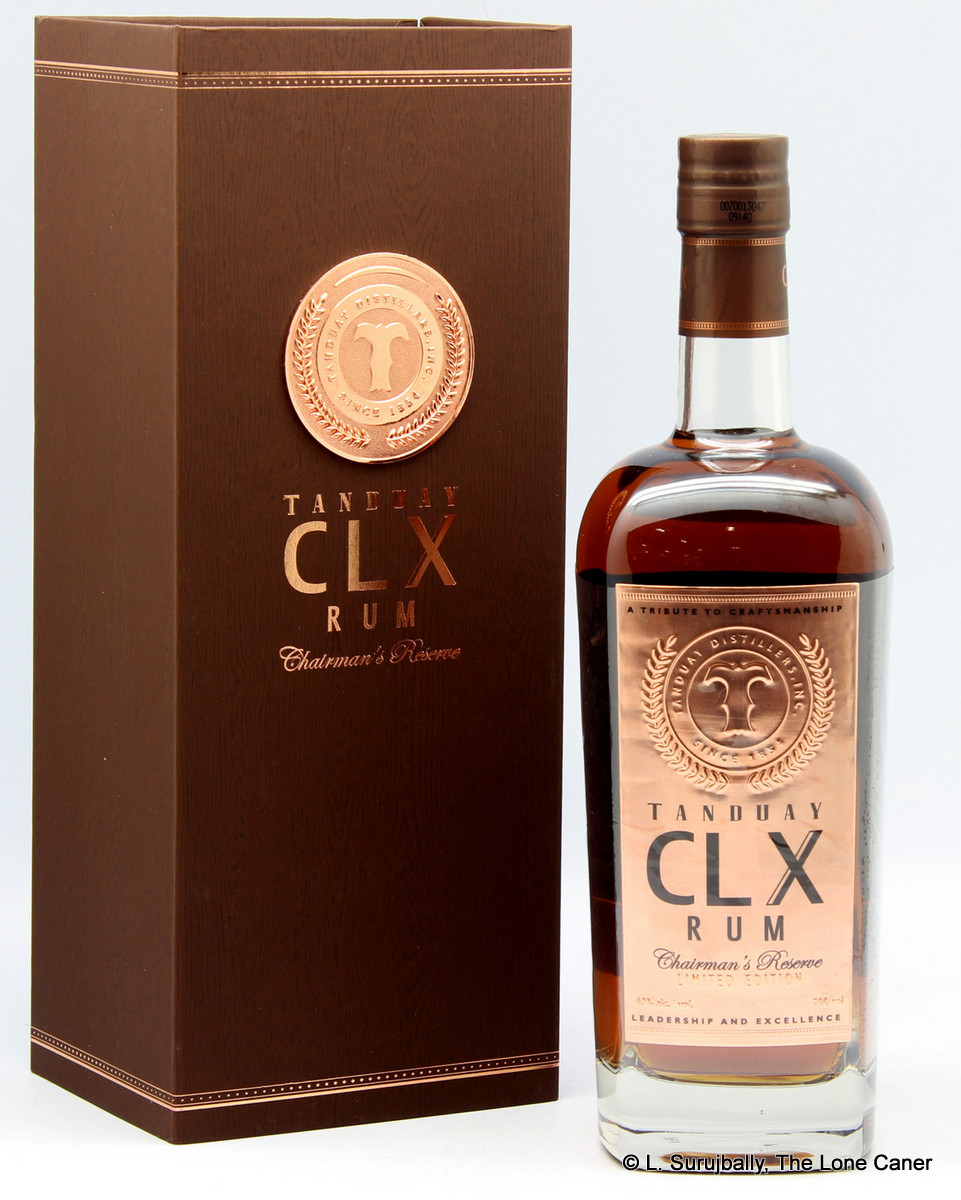

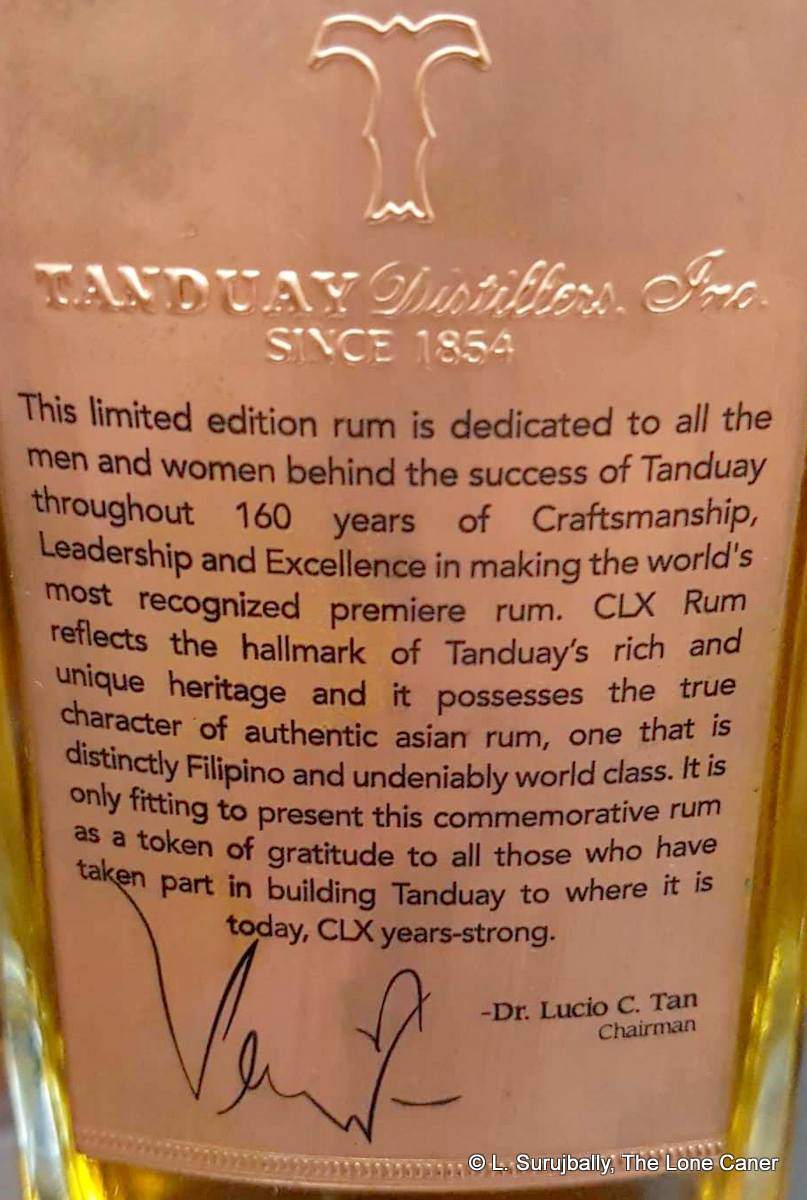

Anyway, when we’re done with do all the contorted company panegyrics and get down to the actual business of trying it, do all the frothy statements of how special it is translate into a really groundbreaking rum?

Anyway, when we’re done with do all the contorted company panegyrics and get down to the actual business of trying it, do all the frothy statements of how special it is translate into a really groundbreaking rum?

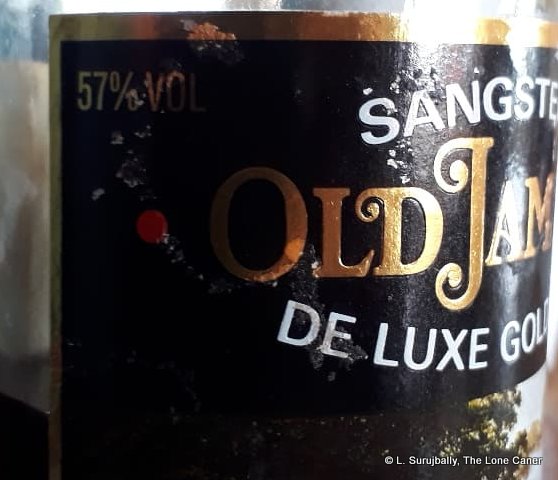

It is unknown from where he sourced his base stock. Given that this DeLuxe Gold rum was noted as comprising pot still distillate and being a blend, it could possibly be Hampden, Worthy Park or maybe even Appleton themselves or, from the profile, Longpond – or some combination, who knows? I think that it was likely between 2-5 years old, but that’s just a guess. References are slim at best, historical background almost nonexistent. The usual problem with these old rums. Note that after Dr. Sangster relocated to the Great Distillery in the Sky, his brand was acquired post-2001 by J. Wray & Nephew who do not use the name for anything except the rum liqueurs. The various blends have been discontinued.

It is unknown from where he sourced his base stock. Given that this DeLuxe Gold rum was noted as comprising pot still distillate and being a blend, it could possibly be Hampden, Worthy Park or maybe even Appleton themselves or, from the profile, Longpond – or some combination, who knows? I think that it was likely between 2-5 years old, but that’s just a guess. References are slim at best, historical background almost nonexistent. The usual problem with these old rums. Note that after Dr. Sangster relocated to the Great Distillery in the Sky, his brand was acquired post-2001 by J. Wray & Nephew who do not use the name for anything except the rum liqueurs. The various blends have been discontinued. Nose – Opens with the scents of a midden heap and rotting bananas (which is not as bad as it sounds, believe me). Bad watermelons, the over-cloying reek of genteel corruption, like an unwashed rum strumpet covering it over with expensive perfume. Acetones, paint thinner, nail polish remover. That is definitely some pot still action. Apples, grapefruits, pineapples, very sharp and crisp. Overripe peaches in tinned syrup, yellow soft squishy mangoes. The amalgam of aromas doesn’t entirely work, and it’s not completely to my taste…but intriguing nevertheless It has a curious indeterminate nature to it, that makes it difficult to say whether it’s WP or Hampden or New Yarmouth or what have you.

Nose – Opens with the scents of a midden heap and rotting bananas (which is not as bad as it sounds, believe me). Bad watermelons, the over-cloying reek of genteel corruption, like an unwashed rum strumpet covering it over with expensive perfume. Acetones, paint thinner, nail polish remover. That is definitely some pot still action. Apples, grapefruits, pineapples, very sharp and crisp. Overripe peaches in tinned syrup, yellow soft squishy mangoes. The amalgam of aromas doesn’t entirely work, and it’s not completely to my taste…but intriguing nevertheless It has a curious indeterminate nature to it, that makes it difficult to say whether it’s WP or Hampden or New Yarmouth or what have you.  Finish – Shortish, dark off-fruits, vaguely sweet, briny, a few spices and musky earth tones.

Finish – Shortish, dark off-fruits, vaguely sweet, briny, a few spices and musky earth tones.

Knowing the Demerara rum profiles as well as I do, and having tried so many of them, these days I treat them all like wines from a particular chateau…or like James Bond movies: I smile fondly at the familiar, and look with interest for variations. Here that was the way to go. The nose suggested an almost woody men’s cologne: pencil shavings, some rubber and sawdust a la PM, and then the flowery notes of a bull squishing happily way in the fruit bazaar. It was sweet, fruity, dark, intense and had a bedrock of caramel, molasses, toffee, coffee, with a great background of strawberry ice cream, vanilla, licorice and ripe yellow mango slices so soft they drip juice. The balance between the two stills’ output was definitely a cut above the ordinary.

Knowing the Demerara rum profiles as well as I do, and having tried so many of them, these days I treat them all like wines from a particular chateau…or like James Bond movies: I smile fondly at the familiar, and look with interest for variations. Here that was the way to go. The nose suggested an almost woody men’s cologne: pencil shavings, some rubber and sawdust a la PM, and then the flowery notes of a bull squishing happily way in the fruit bazaar. It was sweet, fruity, dark, intense and had a bedrock of caramel, molasses, toffee, coffee, with a great background of strawberry ice cream, vanilla, licorice and ripe yellow mango slices so soft they drip juice. The balance between the two stills’ output was definitely a cut above the ordinary.

Whether or not you can place Reunion on a map, you’ve surely heard of at least one of its three distilleries:

Whether or not you can place Reunion on a map, you’ve surely heard of at least one of its three distilleries:

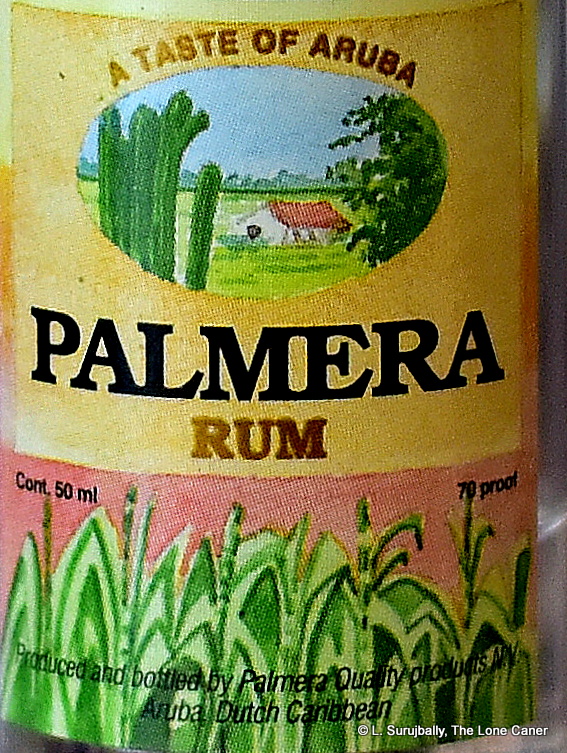

I make this last observation because of its unrefined nature. Even at standard strength, it noses rather raw and jagged, even harsh. There are initial aromas of light glue, rotten bananas and some citrus, light in tone but sharp in attack. It also smells a little sweet and vanilla-like, with vague florals, apple cider, molasses, dates, peaches and dates, with the slightest rtang of burnt rubber coiling around the back there somewhere. But it sears more than caresses and it’s clear that this is not a lovingly aged product of any kind.

I make this last observation because of its unrefined nature. Even at standard strength, it noses rather raw and jagged, even harsh. There are initial aromas of light glue, rotten bananas and some citrus, light in tone but sharp in attack. It also smells a little sweet and vanilla-like, with vague florals, apple cider, molasses, dates, peaches and dates, with the slightest rtang of burnt rubber coiling around the back there somewhere. But it sears more than caresses and it’s clear that this is not a lovingly aged product of any kind.

What it is, is a blend of “select rums” aged two years in sherry casks, issued at 42% and gold-coloured. One can surmise that the source of the molasses is the same as the Noxx & Dunn, cane grown in the state (unless it’s in Puerto Rico). Everything else on the front and back labels can be ignored, especially the whole business about being “hand-crafted,” “small batch” and a “true Florida rum” – because those things give the misleading impression this is indeed some kind of artisan product, when it’s pretty much a low-end rum made in bulk from column still distillate; and I personally think is neutral spirit that’s subsequently aged and maybe coloured (though they deny any additives in the rum).

What it is, is a blend of “select rums” aged two years in sherry casks, issued at 42% and gold-coloured. One can surmise that the source of the molasses is the same as the Noxx & Dunn, cane grown in the state (unless it’s in Puerto Rico). Everything else on the front and back labels can be ignored, especially the whole business about being “hand-crafted,” “small batch” and a “true Florida rum” – because those things give the misleading impression this is indeed some kind of artisan product, when it’s pretty much a low-end rum made in bulk from column still distillate; and I personally think is neutral spirit that’s subsequently aged and maybe coloured (though they deny any additives in the rum). It’s a peculiarity of the sheer volume of rums that cross my desk, my glass and my glottis, that I get to taste rums some people would give their left butt cheek for, while at the same time juice that is enormously well known, talked about, popular and been tried by many….gets missed.

It’s a peculiarity of the sheer volume of rums that cross my desk, my glass and my glottis, that I get to taste rums some people would give their left butt cheek for, while at the same time juice that is enormously well known, talked about, popular and been tried by many….gets missed.

Rumaniacs Review #091 | 0598

Rumaniacs Review #091 | 0598