In late 2018, a relative of this writer was the lead taster of a focus group assembled to test-taste a rum from an Italian company which sought to re-vitalize and even supplant the Velier Demeraras by issuing a rum of their own. Your indolent-but-intrepid reporter has managed to obtain a copy of the official report of Ruminsky Van Drunkenberg, who is, as is widely known (and reported in last year’s authoritative biography of the Heisenberg Distillery) a man with pure 51 year old pot still hooch in his bloodstream, and whose wildly inconsistent analytical powers (depending on his level of alcoholic intake at any given moment) can therefore not be doubted. The report is below.

To: Report to Pietro Caputo, Managing Director, Moustache Spirits, Padua, Italy

From: Investigative Committee representing the focus group

April 1st, 2019

Dear Sir

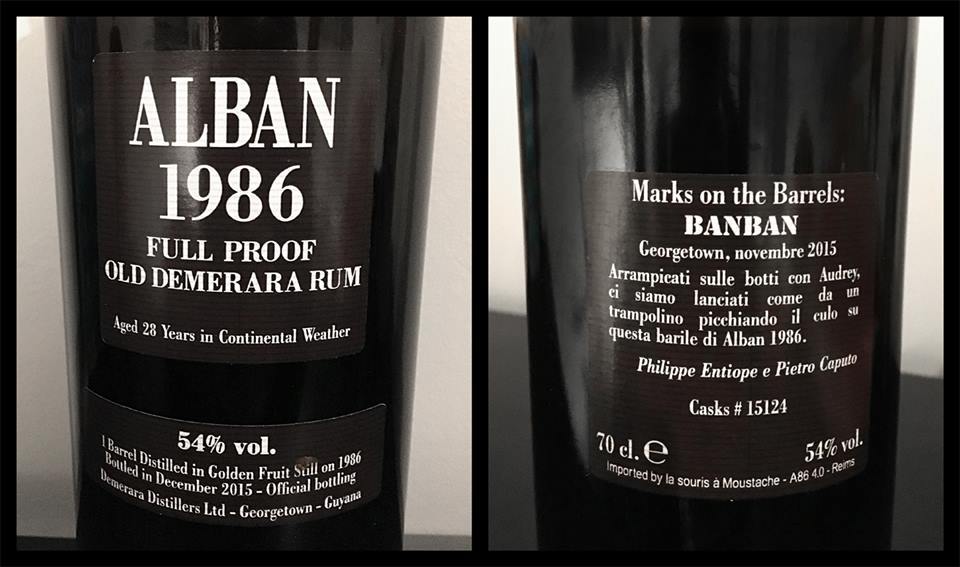

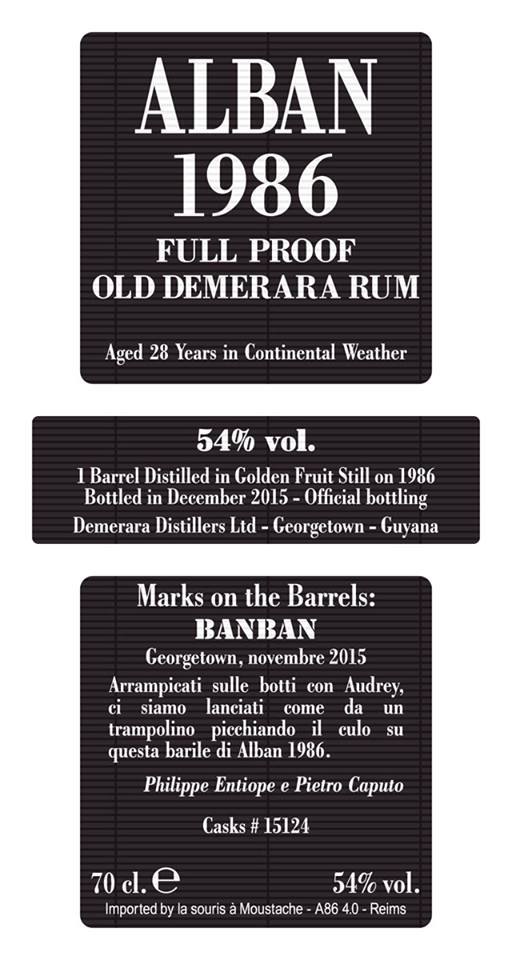

We are pleased to submit our detailed report on the Alban 1986 28 Year Old rum, using as our starting point the company’s website, its marketing materials, and private discussions with Pietro Caputo, Philippe Entiope, Thomas C. and Roger Caroni.

The background narrative, laboratory analyses and blind tasting test results by lesser mortals is attached, but we would like to summarize it with the abstract that follows.

Historical and production background

The rum in question was bottled through the reluctant efforts of the local distillery, who were so loath to lend any assistance to a company whose leftover still wash exceeded their own ultra-super-premium rums without even trying, that they rather resentfully provided some old Velier labels they had kicking around, and escorted Mr. Alban and Moustache Spirits’s Signor Caputo off their premises with gentle words like “Ker yo’ tail from ‘ere!” and “Don’ ever come back!” We are convinced that it is just low-class jealously and envy which lies behind such crude and unbecoming attempts to derail what is already known to be the best rum of its kind in the world.

The Alban 1986, as it is called, is named after the family whose rum-making history stretches back into the 1800s, and was distilled in that year on what has become a legend in upscale ultra-refined rum circles, the “Golden Fruit Still” double retort wooden pot still, owned by the Alban family of Fort Wellington, Berbice, Guyana, right behind the police station at Weldaad. Mr. Stiller Alban, known as “Bathtub” is a constable there and is the Master Distiller in his spare time.

The Albans are distantly related to the Van Rumski Zum Smirnoffs and the Van Drunkenbergs (see attached family tree) who were instrumental in making the Heisenberg mark – there has been discord between the branches of the family for generations, ever since Stiller Alban’s grandfather Grogger (known as ‘Suck-teet’) reputedly stole the still from the Heisenberg plantation nearly a century ago; the issue remains unconfirmed since none of the family members can speak coherently about any other without spitting, cursing and lapsing into objurgatory creole. While Mr. Alban could not be reached for comment, his younger twin brothers Hooter and Shooter (respectively known in the area as “Dopey” and “Sleepy” Alban) told this Committee that the distillate was the best variety “Roraima Blue Platinum” cane grown in the area. This varietal apparently is not found anywhere else on earth, and is so rich in sucrose that locals just cut it into pieces and dunk it into their coffee. Kew Gardens in London have tried to get a sample for hundreds of years, but it remains fiercely guarded by the Albans, on whose little plantation alone it is found. It is considered the purest and most distinctive iteration of terroire and parcellaire on the planet.

Messrs. Hooter and Shooter Alban confirmed that the wooden double retort pot still (of their own family’s design and manufacture) remained operational, and fiercely denied any suggestion that it had once belonged to, or was made by, either Tipple Heisen or Chugger Van Drunkenberg. “We great-granfadder Puante “Stink Bukta*” d’Alban and he son Banban mek dat ting,” they both said indignantly when the subject was brought up. “He cut de greenheart and wallaba wood heself, he forge de rivets and de condensing coil and put de whole ting togedder wit Banban. Dem rascally tief-man over in Enmore ain’ got de sense God give a three-day-old-dead fish, but dem plenty jealous,” they said.

Grogger Alban reportedly laid a few barrels away in 1986 to commemorate the birth of the twins, and bottled the casks when they finally learnt to write their own names the same way twice (in 2015). However, for all its age, the rum is clearly modest in its aims, as, for one thing, it does not wish to dethrone the G&M Long Pond 1941 58 YO as the oldest rum ever made, being issued at a mere 28 years — but strenuous tasting tests and the marketing materials show that without doubt the core elements of the Alban 1986 are many decades older.

Because the producers don’t want riots and mobs of angry and jealous producers coming to their doors demanding to share in the remarkable production discoveries that have resulted in this modern-day elixir (which may even reverse one’s age – tests are ongoing), production details are a closely guarded secret in a Swiss-made security vault under Cheyenne Mountain. We recommend a complete news blackout on the still, the true age, and the components which make it up and even the country and distillery from which it originates. As a further security measure to safeguard its unique heritage and quality, it is not going into general release but is available by subscription only, with rigorous checking of credentials to ensure only true rum lovers will be able to get one of the extraordinarily limited editions of the rum (100 bottles made, of which this one is #643)

Production and Tasting Notes

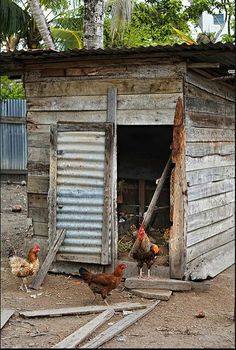

The Grande Maison where the Golden Fruit Still is housed, behind the police station at Weldaad.

The cane stalks are cut individually by hand using only the finest Japanese, hand-forged CPM S110V steel cutlasses. They are transported to the still behind the Weldaad police station by donkey cart, before being meticulously, one by one, crushed with a pair of diamond-forged pliers made in Patagonia. The juice is left to ferment in a wooden tub with wild yeast for seventeen days and three hours precisely before being fed into the Golden Fruit still. It emerges as pure rum and is then run into barrels made of French Oak, the staves of which family lore states come from the stolen furniture of the French royal palace where an ancestor once served before absconding to the Caribbean.

Exhaustive laboratory analysis shows that the rum is self-evidently made from the distilled tears of virgins mixed with pure gold in solution, and the ageing barrels have been blessed personally by the pope — there can be no other rational explanation for a rum of such exceptional quality. The strength is tested and labelled to be a flaccid 54% – though our peer-reviewed post-doctoral psychologists maintain that only narcissistic literary wannabes and sneering uber-mensches with delusions of Godhood and doubts about their masculinity would ever venture above that – and in any case, hydrometer tests have proved the strength to be actually 80%, which means that unlike dosed rums where the labelled ABV is greater than the tested ABV (here the reverse is true) something has been taken out, rather than put in – and the Alban 1986 is therefore the purest rum ever made in history.

Each stalk of sugar cane is individually handpicked and individually brought to the distillery on a donkey cart. In the picture: Grogger and Stiller “Bathtub” Alban, circa 2008

On the nose, this is simply the best, most powerful, the most complex nose imaginable. It not only was the best of all caramels, toffees and Kopi Luwak coffees available, but went beyond them into uncharted waters of such superlative aromas that they were observed to make a statue of the Virgin Mary in St Peter’s weep. Scents of only the purest Sorrento and Italian lemons curled around the brininess created by ultra-pure Himalayan pink salt fetched out of Nepal by teams of matched white yaks raised from infancy by the Dalai Lama. The exquisite layering of aromas of Lambda olive oil (from individually caressed Koroneiki olives) with the sweet stench of hogos gone wild suggest that Luca Gargano’s NRJ Long Pond TECA was an unsuccessful attempt to copy the amazing olfactory profile presented by this superlative rum, although which traitorous wretch in the Committee was so crass as to purloin a sample and smuggle it to Genoa for Mr. Gargano to (unsuccessfully) duplicate remains under investigation at this time.

The Committee members all agree that the perfection of the balance and assembly, the coherence of the various aspects of taste and flavour make it a rum so flawless that no rival has ever been discovered, tasted or recorded in the world history of rumology. The rum is so smooth to taste that silk-weavers from China and vicuña-herders in Peru have reportedly burst into tears at the mere sight of a glass holding this ambrosia, and spies from an unnamed and as-yet unlocated Colombian distillery have been seen loitering around the premises hoping to score a sample to see how the redefinition of “smooth” was accomplished. There are notes of 27 different varieties of apples, plus 14 kinds of citrus fruit, to which has been added a variety of uber-expensive spices from a 3-star Michelin chef’s pantry – we identified at least cumin, marsala, rosemary, thyme, sage, fennel and coriander. And in addition, we noted an amalgam of kiwi-fruit, sapodilla, gooseberries, black cherries, guavas, mangos (from Thailand, Kenya, Madagascar, India, Trinidad and the Philippines), and this was melded impeccably with the creamy flavours of six different types of out-of-production Haagen-Dasz ice cream.

One member of the team opined that many rums fall off on the finish. This is clearly not the case here. The rum’s final fading notes lasted for six days, and so incredibly rich and lasting was the close, that some members of the team – after making the mistake of trying Mr. Van Drunkenberg’s “Black Wasp Legal Lip Remover” pepper sauce – hastened to the toilet with tasting glasses held in one hand and two rolls of paper in the other, because the Alban’s long lasting aromas killed all forms of perfume, cologne, smell, stink, stench and odiferous meat cold stone dead. The sweet aromas and closing notes of flowers, fruits, smoke, leather, caramel, molasses and cane juice not only rival but far exceed any unaged clairin, agricole, traditionnel, pisco, tequila, wine, brandy, cognac, port or 70 year old single malt ever made, and for this reason we have no hesitation in giving it the score we do.

(#612)(150/100)

Opinion and Conclusion

As noted in Part II, Section 4, Exhibit F, Subpart 2.117, Clause (viii) (paragraphs 4 and 5) of our abbreviated report, it is now obvious that La Souris à Moustache has managed to obtain and bottle the wildest, most potent, Adonis-like rums ever bottled, and recommend that strong health and safety advisories be slapped on the label for the benefit of puling wussies who refer to a 38% underproof as “exemplary.” The Alban 1986 is definitely not for such persons but we must not be indifferent to the potential health hazards to the unwary and inexperienced.

We recommend that the target audience be limited to macho Type A personalities who drink the Marienburg 90 neat (or mixed with, perhaps, an Octomore). In an effort to assess who had the cojones to drink this and continue breathing, we issued tots to various special forces of the world’s elite militaries. We found that Seal Team 6 uses this rum as part of Hell Week to weed out people whose minds aren’t on the job…because most who drink it go straight to ring the bell, and leave the camp to sign up for distilling classes, knowing that no endeavour of theirs will ever come close to the ability to make rum like this. Those who survive it can use the empty bottle for bench presses where, it is rumoured, only Donald Trump ever managed to get it all the way up.

When we provided a 100-page NDA and a sample to the writer of a largely unread and anonymous blog which we cannot, for copyright reasons, name publicly (the Lone Caner), our consultant started scribbling right away and was still nosing it eight days later, with a War and Peace sized series of tasting notes. He wept copious tears (of gratitude) and thanked us (profusely) for providing him with a sample of a rum whose profile was so spectacular that he was thinking of rating it 110 points. Such exuberance and enthusiasm for your rum is, by the way, not unusual in our focus group and selected purchasers.

In short, it is clear to all of us who have been exposed to it, that this is without question the best rum ever made. Of any kind. At any strength. Of any age. From any country. “None of the Veliers even come close!” opined our focus group with becomingly modest rapture. “It leaves Foursquare, Worthy Park and Hampden playing catch-up by sprinting ahead into realms of quality heretofore only dreamed about,” was noted by another less effusive blogger whose allocation we may want to review – he isn’t using proper level of praise (although in his defense, he had just come back from visiting the estates in question and couldn’t stop babbling about his infatutation with Ms. Harris and her famed red ensemble, as evidenced by his constant moon-struck, doofus-like expression throughout the tasting session).

Summing up, then, we feel that La Souris à Moustache should lose no time in releasing the Alban 1986 28 Year Old Full Proof rum to the market at a price commensurate with its quality, and limit each purchaser to a sample-sized 1cl bottle. More is not required and indeed may be counterproductive, as people who drink it might want to expire immediately out of sheer despair, knowing that there will never be a rum better than this one and that the Everest of rumdom has been summitted.

Yours Truly

Mr. Ruminsky van Drunkenberg (Visiting Lecturer, Heisenberg Rum Institute, Port Mourant Guyana), with research and additional nosing by Sipper “The Tot” Van Drunkenberg.

This report has been researched, compiled, collated and vetted by the best Rum Experts from the best blogs ever ever, and is verifiably not the purchased mouthings of an insecure and unappreciated shill consumed by his own mediocrity, insecurity, jealousy or vanity. We certify that the complete report as attached is therefore really really true, and can be trusted to underpin the marketing campaign called Make Rum Great Again as defined and delineated in Appendix B Subsection 5.1, whenever it is felt appropriate to commence.

Glossary

*“Bukta” – Guyanese slang for (inevitably shabby) male underwear.

Acknowledgements

Photographs, label design and conceptual ideas courtesy of Thomas C., Pietro Caputo, Philippe Entiope and Alban Christophe, whose sly senses of humour have informed this completely honest, unbiased and uninformed report on the Alban rum, and the history of the families involved.

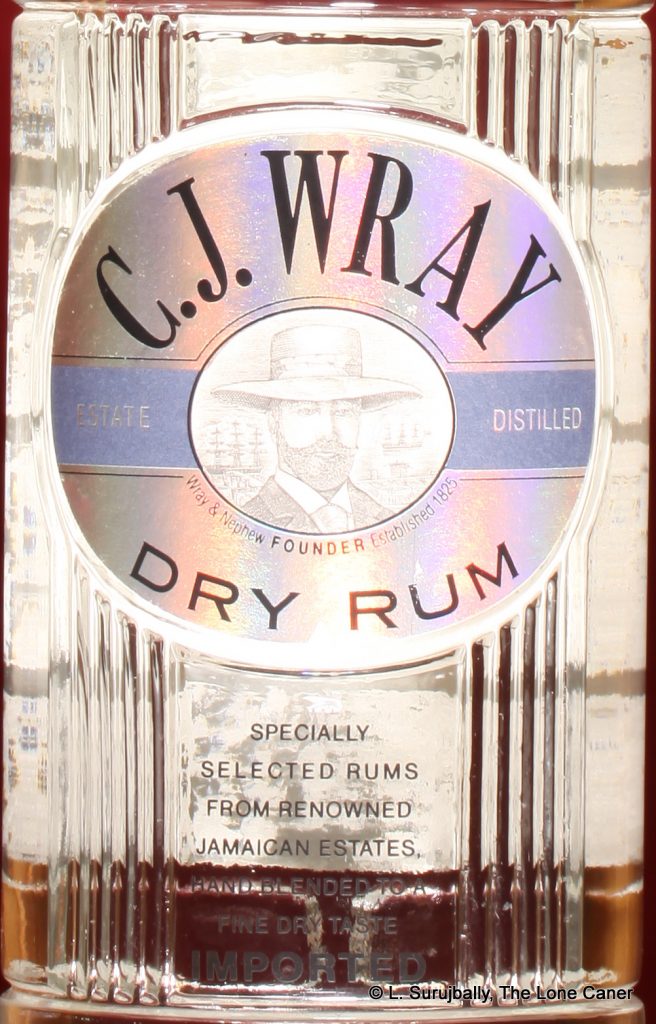

Nose – Starts off with plastic, rubber and acetones, which speak to its (supposed) unaged nature; then it flexes its cane-juice-glutes and coughs up a line of sweet water, bright notes of grass, sugar cane sap, brine and sweetish red olives. It’s oily, smooth and pungent, with delicate background notes of dill and cilantro lurking in the background. And some soda pop.

Nose – Starts off with plastic, rubber and acetones, which speak to its (supposed) unaged nature; then it flexes its cane-juice-glutes and coughs up a line of sweet water, bright notes of grass, sugar cane sap, brine and sweetish red olives. It’s oily, smooth and pungent, with delicate background notes of dill and cilantro lurking in the background. And some soda pop.

Colour – Gold

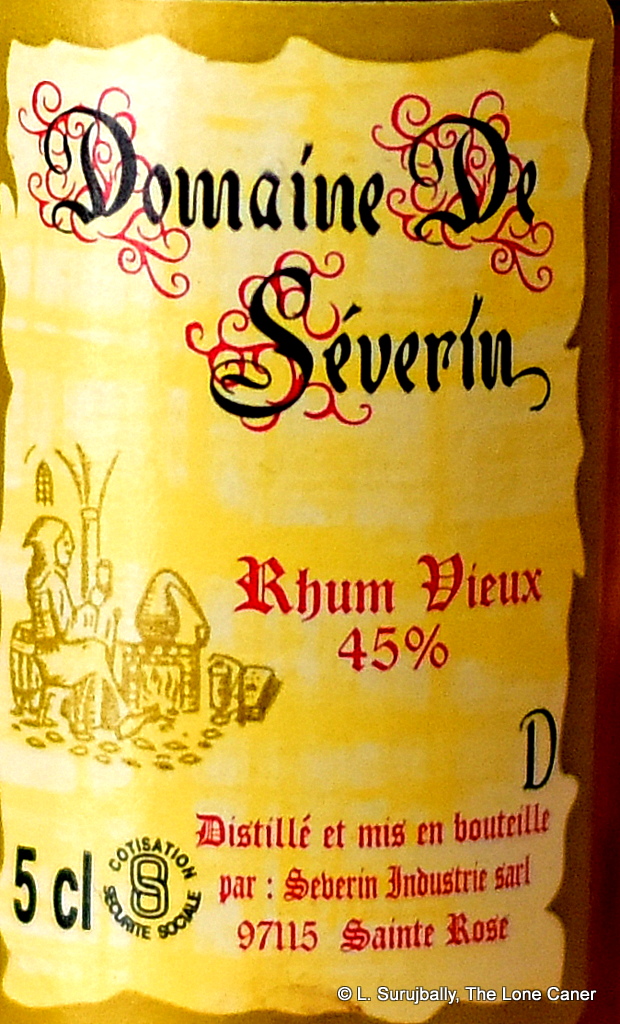

Colour – Gold Whether or not you can place Reunion on a map, you’ve surely heard of at least one of its three distilleries:

Whether or not you can place Reunion on a map, you’ve surely heard of at least one of its three distilleries:

I make this last observation because of its unrefined nature. Even at standard strength, it noses rather raw and jagged, even harsh. There are initial aromas of light glue, rotten bananas and some citrus, light in tone but sharp in attack. It also smells a little sweet and vanilla-like, with vague florals, apple cider, molasses, dates, peaches and dates, with the slightest rtang of burnt rubber coiling around the back there somewhere. But it sears more than caresses and it’s clear that this is not a lovingly aged product of any kind.

I make this last observation because of its unrefined nature. Even at standard strength, it noses rather raw and jagged, even harsh. There are initial aromas of light glue, rotten bananas and some citrus, light in tone but sharp in attack. It also smells a little sweet and vanilla-like, with vague florals, apple cider, molasses, dates, peaches and dates, with the slightest rtang of burnt rubber coiling around the back there somewhere. But it sears more than caresses and it’s clear that this is not a lovingly aged product of any kind.

What it is, is a blend of “select rums” aged two years in sherry casks, issued at 42% and gold-coloured. One can surmise that the source of the molasses is the same as the Noxx & Dunn, cane grown in the state (unless it’s in Puerto Rico). Everything else on the front and back labels can be ignored, especially the whole business about being “hand-crafted,” “small batch” and a “true Florida rum” – because those things give the misleading impression this is indeed some kind of artisan product, when it’s pretty much a low-end rum made in bulk from column still distillate; and I personally think is neutral spirit that’s subsequently aged and maybe coloured (though they deny any additives in the rum).

What it is, is a blend of “select rums” aged two years in sherry casks, issued at 42% and gold-coloured. One can surmise that the source of the molasses is the same as the Noxx & Dunn, cane grown in the state (unless it’s in Puerto Rico). Everything else on the front and back labels can be ignored, especially the whole business about being “hand-crafted,” “small batch” and a “true Florida rum” – because those things give the misleading impression this is indeed some kind of artisan product, when it’s pretty much a low-end rum made in bulk from column still distillate; and I personally think is neutral spirit that’s subsequently aged and maybe coloured (though they deny any additives in the rum).

Until

Until

Given that it is nine years tropical ageing plus another year in the Sauternes casks, I think we could be expected to have a pretty interesting profile — and I wasn’t disappointed (though the low 41% strength did give me pause). The initial smells were grassy and wine-y at the same time, a combination of musk and crisp light aromas that melded well. There were green apples, grapes, the tart acidity of cider mixed in with some ginger and cinnamon, a dollop of brine and a few olives, freshly mown wet grass and well-controlled citrus peel behind it all.

Given that it is nine years tropical ageing plus another year in the Sauternes casks, I think we could be expected to have a pretty interesting profile — and I wasn’t disappointed (though the low 41% strength did give me pause). The initial smells were grassy and wine-y at the same time, a combination of musk and crisp light aromas that melded well. There were green apples, grapes, the tart acidity of cider mixed in with some ginger and cinnamon, a dollop of brine and a few olives, freshly mown wet grass and well-controlled citrus peel behind it all.  It’s a peculiarity of the sheer volume of rums that cross my desk, my glass and my glottis, that I get to taste rums some people would give their left butt cheek for, while at the same time juice that is enormously well known, talked about, popular and been tried by many….gets missed.

It’s a peculiarity of the sheer volume of rums that cross my desk, my glass and my glottis, that I get to taste rums some people would give their left butt cheek for, while at the same time juice that is enormously well known, talked about, popular and been tried by many….gets missed.

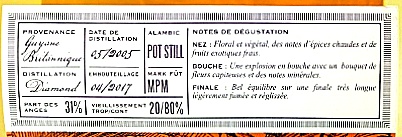

Rumaniacs Review #091 | 0598

Rumaniacs Review #091 | 0598

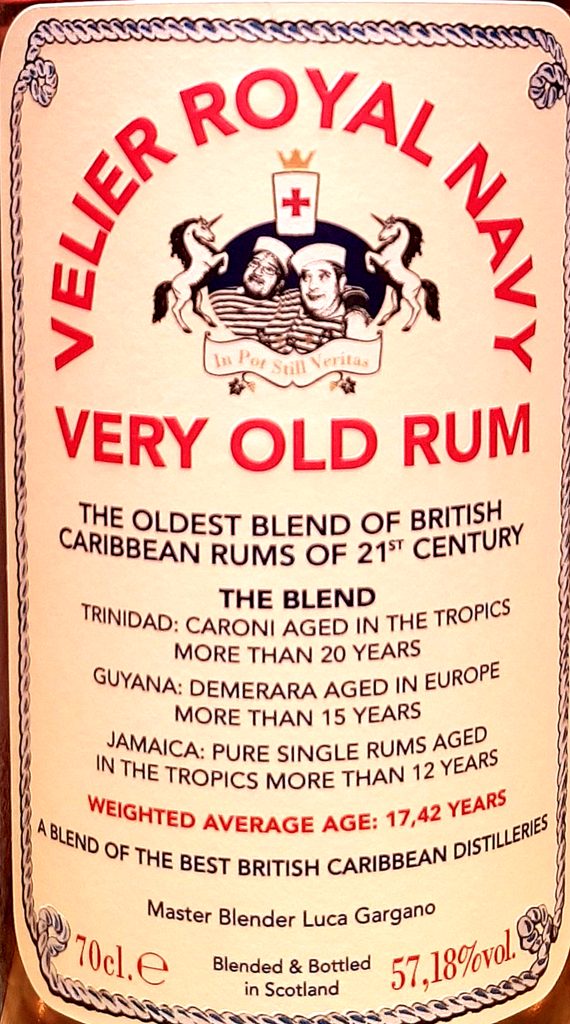

The nose suggested that this wasn’t far off. Mild for the strength, warm and aromatic, the first notes were deep petrol-infused salt caramel ice cream (yeah, I know how that sounds). Combining with that were some rotten fruit aromas (mangoes and bananas going off), brine and olives that carried the flag for the Jamaicans, with sharp bitter woody hints lurking around; and, after a while, fainter wooden and licorice notes from the Mudlanders (I’d suggest Port Mourant but could be the Versailles, not sure). I also detected brown sugar, molasses and a sort of light sherry smell coiling around the entire thing, together with smoke, leather, wood, honey and some cream tarts. Quite honestly, there was so much going on here that it took the better part of an hour to get through it all. It may be a navy grog, but definitely is a sipper’s delight from the sheer olfactory badassery.

The nose suggested that this wasn’t far off. Mild for the strength, warm and aromatic, the first notes were deep petrol-infused salt caramel ice cream (yeah, I know how that sounds). Combining with that were some rotten fruit aromas (mangoes and bananas going off), brine and olives that carried the flag for the Jamaicans, with sharp bitter woody hints lurking around; and, after a while, fainter wooden and licorice notes from the Mudlanders (I’d suggest Port Mourant but could be the Versailles, not sure). I also detected brown sugar, molasses and a sort of light sherry smell coiling around the entire thing, together with smoke, leather, wood, honey and some cream tarts. Quite honestly, there was so much going on here that it took the better part of an hour to get through it all. It may be a navy grog, but definitely is a sipper’s delight from the sheer olfactory badassery.

Technical details are murky. All right, they’re practically non-existent. I think it’s a filtered column still rum, diluted down to standard strength, but lack definitive proof – that’s just my experience and taste buds talking, so if you know better, drop a line. No notes on ageing – however, in spite of one reference I dug up which noted it as unaged, I think it probably was, just a bit.

Technical details are murky. All right, they’re practically non-existent. I think it’s a filtered column still rum, diluted down to standard strength, but lack definitive proof – that’s just my experience and taste buds talking, so if you know better, drop a line. No notes on ageing – however, in spite of one reference I dug up which noted it as unaged, I think it probably was, just a bit.

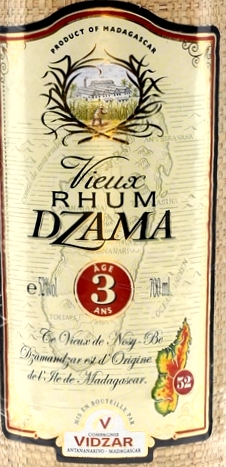

All that said, there isn’t much on the company website about the technical details regarding the 3 year old we’re looking at today. It’s a column still rum, unadded-to, aged in oak barrels, and my sample clocked in at 52%, which I think is an amazing strength for a rum so young – most producers tend to stick with the tried-and-true 40-43% (for tax and export purposes) when starting out, but not these guys.

All that said, there isn’t much on the company website about the technical details regarding the 3 year old we’re looking at today. It’s a column still rum, unadded-to, aged in oak barrels, and my sample clocked in at 52%, which I think is an amazing strength for a rum so young – most producers tend to stick with the tried-and-true 40-43% (for tax and export purposes) when starting out, but not these guys.

That’s not to say that in this case the

That’s not to say that in this case the