This is a rhum to drive you to tears, or transports of ecstasy, because it’s almost guaranteed that either you’ll regret you never tried it (though you’ll only know that after you do), or fall in lust with it immediately, then bang yourself over the head for not buying more when you did. It’s a white rhum screwed tight to a screaming 60%, unaged, and made, Lord save us, from St. James’s old pot stills — which created a juice so unlike anything else from the island that people crossed themselves when they saw it, it couldn’t be labelled as an AOC, could not even be designated as Martinique rhum, and all we get is the almost embarrassed note that it’s made from “French Antilles.”

White rhums like this have a strong and cheerfully disreputable DNA, going back right to the beginning when all the various estates and plantations had was leaky, farty stills slapped together from cast-aside copper, steel dinner plates and maybe a leather shoe or three. We’ve had primitives like this before – the Sajous and the Paranubes come to mind, Sangar from Liberia, MIM from Ghana, South Africa’s Mhoba, the Barik rhums from Moscoso’s jury rigged column still, and even Habitation Velier’s 2013 Foursquare and TECA whites, and that mastodon of the L’Esprit from Guyana. Yet I assure you, this innocent and demure looking pale yellow-white was on a level all its own, not just because of its origins, but because it hearkens back to rum’s origins while not forgetting a single damn thing St. James have ever learned in over two hundred years, about how to make sh*t that knocks you flat.

And also because, man, did this thing ever smell pungent — it was a bottle-sized 60-proof ode to whup-ass and rumstink. A barrage of nail polish, spoiling fruit, wood chips, wax, salt, and gluey notes all charged right out without pause or hesitation, spoiling for a fight. Even without making a point of it, the rhum unfolded with uncommon firmness into aromas of sweet, grassy herbals, green apples, sugar water, dill, cider, vegetables, toasted bread, a sharp mature cheddar, all mixed in with moist dark earth, sugar water, biscuits, orange peel. And the balance of all of them was really quite good, truly.

And also because, man, did this thing ever smell pungent — it was a bottle-sized 60-proof ode to whup-ass and rumstink. A barrage of nail polish, spoiling fruit, wood chips, wax, salt, and gluey notes all charged right out without pause or hesitation, spoiling for a fight. Even without making a point of it, the rhum unfolded with uncommon firmness into aromas of sweet, grassy herbals, green apples, sugar water, dill, cider, vegetables, toasted bread, a sharp mature cheddar, all mixed in with moist dark earth, sugar water, biscuits, orange peel. And the balance of all of them was really quite good, truly.

Could the palate live up to all that stuff I was smelling? I got the impression it was sure trying, and it displayed an uncommon lack of roughness and jagged edges for something at that strength (the L’Esprit 85% white had a similar quality, you’ll recall). It slid smoothly across the tongue before hijacking it with tastes of sugar water, white chocolate, almonds cumin, citrus peel and brine. Then, as if unsatisfied, it added ashes, warm bread fresh from the oven, ginger snaps, cloves, soursop…in all that time it never crossed into something excessively sweet or allowed any one element to dominate the others, and while it lacked the true complexity of a rhum I would call “great”, it didn’t fall much short either, and the finish wrapped things up with a flourish – warm, really long, with ginger, cinnamon, herbs, citrus peel and bitter chocolate and sea salt.

Until 2019, the Coeur de Chauffe — “the Heart of the Distillation” — was an underground cult rum limited to no more than 5000 liters per year, sold only on Martinique itself. It is, in point of fact, not an AOC rhum at all since it is a pot still product. Having tried it twice now and come to grips with its elemental nature, I think of it as a throwback, an ancestor, an old-style white agricole from Ago. I appreciate it’s a rhum that will likely find only a niche audience and is not for the sweet-toothed who love gentler products; but anyone who loves his juice should one day try sampling something like this, if only to experience new tastes, or old ones expressed in different ways. I drank it with St. James’s own more traditional Fleur de Canne 50% and some of DePaz’s work — yet somehow, even though they were all good, all tasty, it’s this one I remember for its fire and its taste and its furious energy. Clearly something so pungent and unique could not be kept hidden forever, and for all those looking for something interesting, perhaps even an alternative to some of Jamaica’s funky bad boys, well, here may just be the droid you’re looking for.

(#656)(86.5/100)

I’ll get straight to it, then, and merely mention that at 85% ABV, care was taken – I poured, covered the glass, waited, removed the cover, and prudently stepped way back.

I’ll get straight to it, then, and merely mention that at 85% ABV, care was taken – I poured, covered the glass, waited, removed the cover, and prudently stepped way back.

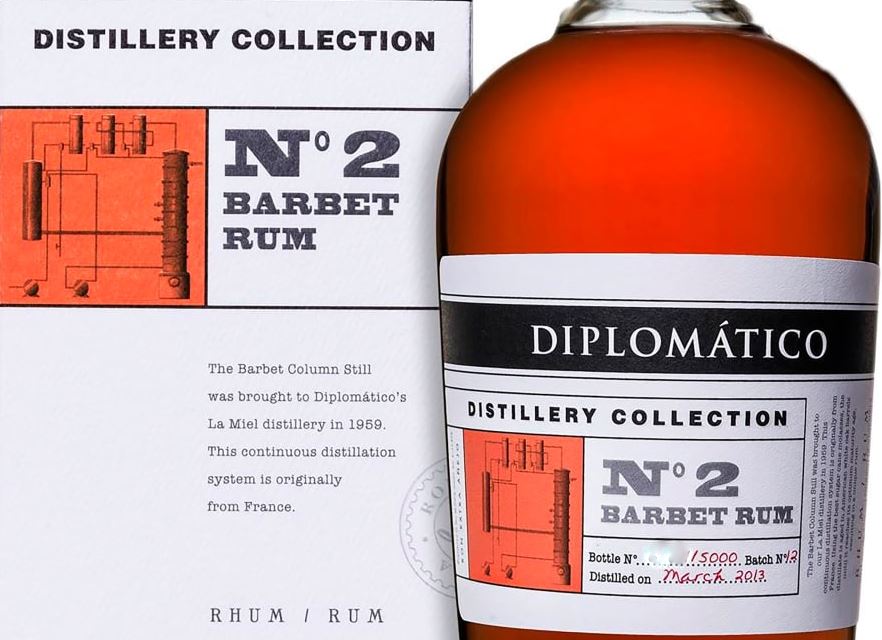

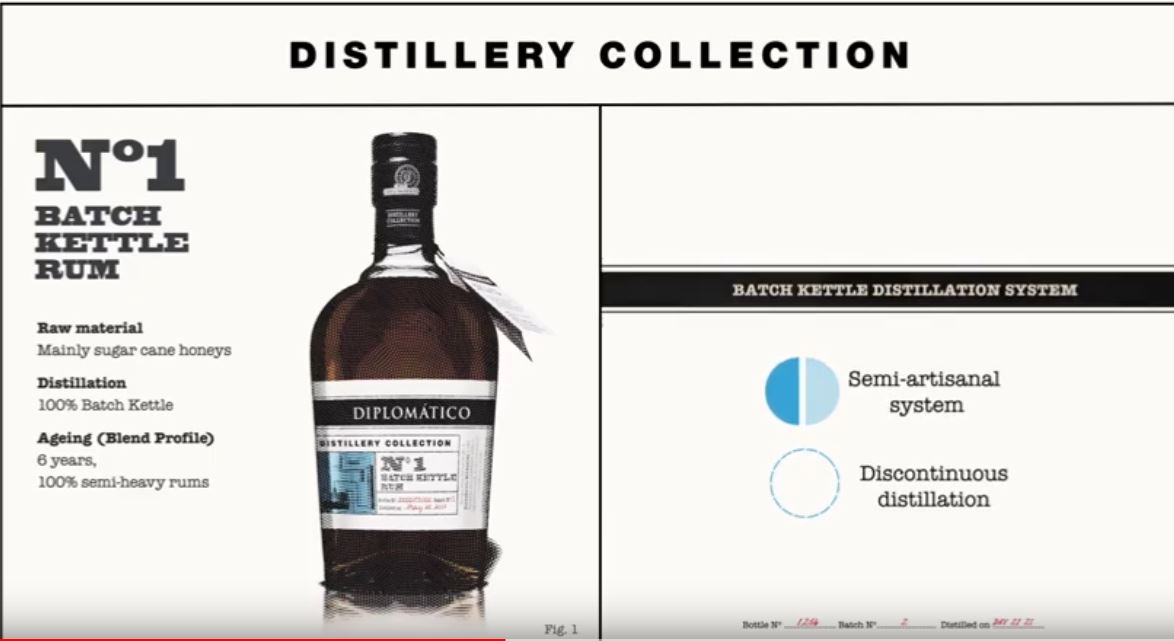

Things took an interesting turn around 2017 when No.1 and No.2 versions of the “Distillery Collection” were trotted out with much fanfare. The purpose of the Collection was to showcase other stills they had – a “kettle” (sort of a boosted pot still, for release No.1), a Barbet continuous still (release No.2) and an undefined pot still (release No.3, released in April 2019). These stills, all of which were acquired the year the original company was founded, in 1959, were and are used to provide the distillates which are blended into their various commercial marques, and until recently, such blends were all we got. One imagines that they took note of DDL’s killer app and the rush by Jamaica and St Lucia to work with the concept and decided to go beyond their blended range into something more specific.

Things took an interesting turn around 2017 when No.1 and No.2 versions of the “Distillery Collection” were trotted out with much fanfare. The purpose of the Collection was to showcase other stills they had – a “kettle” (sort of a boosted pot still, for release No.1), a Barbet continuous still (release No.2) and an undefined pot still (release No.3, released in April 2019). These stills, all of which were acquired the year the original company was founded, in 1959, were and are used to provide the distillates which are blended into their various commercial marques, and until recently, such blends were all we got. One imagines that they took note of DDL’s killer app and the rush by Jamaica and St Lucia to work with the concept and decided to go beyond their blended range into something more specific.

What’s all the more astounding about

What’s all the more astounding about  Based on how it initially nosed, I started out believing this was a wooden still — by the end, I was no longer so sure. The profile actually reminded me more of the

Based on how it initially nosed, I started out believing this was a wooden still — by the end, I was no longer so sure. The profile actually reminded me more of the

First off, it’s a 40% rum, white, and filtered, so the real question is what’s the source? The back label remarks that it’s made from “first pressing of virgin Maui sugar cane” (as opposed to the slutty non-Catholic kind of cane, I’m guessing) but the

First off, it’s a 40% rum, white, and filtered, so the real question is what’s the source? The back label remarks that it’s made from “first pressing of virgin Maui sugar cane” (as opposed to the slutty non-Catholic kind of cane, I’m guessing) but the  With some exceptions, American distillers and their rums seem to operate along such lines of “less is more” — the exceptions are usually where owners are directly involved in their production processes, ultimate products and the brands. The more supermarket-level rums give less information and expect more sales, based on slick websites, well-known promoters, unverifiable-but-wonderful origin stories and enthusiastic endorsements. Too often such rums (even ones labelled “Super Premium” like this one) when looked at in depth, show nothing but a hollow shell and a sadly lacking depth of quality. I can’t entirely say that about the Beach Bar Rum – it does have some nice and light notes, does not taste added-to and is not unpleasant in any major way – but the lack of information behind how it is made, and its low-key profile, makes me want to use it only for exactly what it is made: not neat, and not to share with my rum chums — just as a relatively unexceptional daiquiri ingredient.

With some exceptions, American distillers and their rums seem to operate along such lines of “less is more” — the exceptions are usually where owners are directly involved in their production processes, ultimate products and the brands. The more supermarket-level rums give less information and expect more sales, based on slick websites, well-known promoters, unverifiable-but-wonderful origin stories and enthusiastic endorsements. Too often such rums (even ones labelled “Super Premium” like this one) when looked at in depth, show nothing but a hollow shell and a sadly lacking depth of quality. I can’t entirely say that about the Beach Bar Rum – it does have some nice and light notes, does not taste added-to and is not unpleasant in any major way – but the lack of information behind how it is made, and its low-key profile, makes me want to use it only for exactly what it is made: not neat, and not to share with my rum chums — just as a relatively unexceptional daiquiri ingredient.

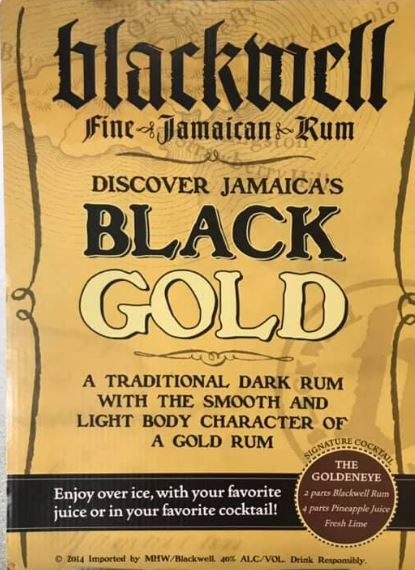

With all due respect to the makers who expended effort and sweat to bring this to market, I gotta be honest and say the Blackwell Fine Jamaican Rum doesn’t impress. Part of that is the promo materials, which remark that it is “A traditional dark rum with the smooth and light body character of a gold rum.” Wait, what? Even Peter Holland usually the most easy going and sanguine of men, was forced to ask in

With all due respect to the makers who expended effort and sweat to bring this to market, I gotta be honest and say the Blackwell Fine Jamaican Rum doesn’t impress. Part of that is the promo materials, which remark that it is “A traditional dark rum with the smooth and light body character of a gold rum.” Wait, what? Even Peter Holland usually the most easy going and sanguine of men, was forced to ask in  With respect to the good stuff from around the island — and these days, there’s so much of it sloshing about — this one is feels like an afterthought, a personal pet project rather than a serious commercial endeavour, and I’m at something of a loss to say who it’s for. Fans of the quiet, light rums of twenty years ago? Tiki lovers? Barflies? Bartenders? Beginners now getting into the pantheon? Maybe it’s just for the maker — after all, it’s been around since 2012, yet how many of you can actually say you’ve heard of it, let alone tried a shot?

With respect to the good stuff from around the island — and these days, there’s so much of it sloshing about — this one is feels like an afterthought, a personal pet project rather than a serious commercial endeavour, and I’m at something of a loss to say who it’s for. Fans of the quiet, light rums of twenty years ago? Tiki lovers? Barflies? Bartenders? Beginners now getting into the pantheon? Maybe it’s just for the maker — after all, it’s been around since 2012, yet how many of you can actually say you’ve heard of it, let alone tried a shot?

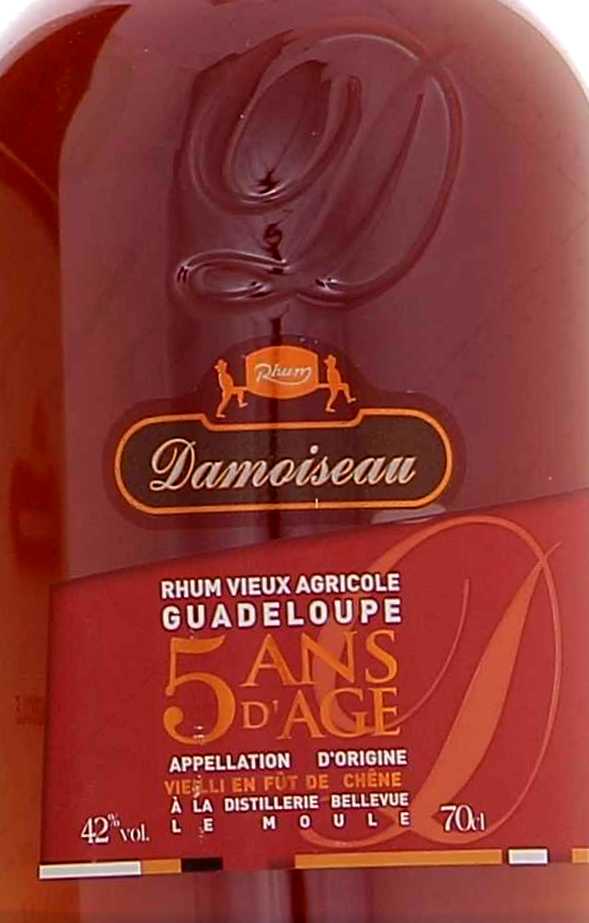

Unlike many aged agricoles that have run into my glass (and down my chin), I found this one to be quite sweet, and for all the solidity of the strength, also rather scrawny, a tad sharp. At least at the beginning, because once a drop of water was added and I chilled out a few minutes, it settled down and it tasted softer, earthier, muskier. Creamy salt butter on black bread, sour cream, yoghurt, and also fried bananas, pineapple, anise, lemon zest, cumin, raisins, green grapes, and a few more background fruits and florals, though these never come forward in any serious way. The finish is excellent, by the way – some vague molasses, burnt sugar, the creaminess of hummus and olive oil, caramel, flowers, apples and some tart notes of soursop and yellow mangoes and maybe a gooseberry or two. Nice.

Unlike many aged agricoles that have run into my glass (and down my chin), I found this one to be quite sweet, and for all the solidity of the strength, also rather scrawny, a tad sharp. At least at the beginning, because once a drop of water was added and I chilled out a few minutes, it settled down and it tasted softer, earthier, muskier. Creamy salt butter on black bread, sour cream, yoghurt, and also fried bananas, pineapple, anise, lemon zest, cumin, raisins, green grapes, and a few more background fruits and florals, though these never come forward in any serious way. The finish is excellent, by the way – some vague molasses, burnt sugar, the creaminess of hummus and olive oil, caramel, flowers, apples and some tart notes of soursop and yellow mangoes and maybe a gooseberry or two. Nice.

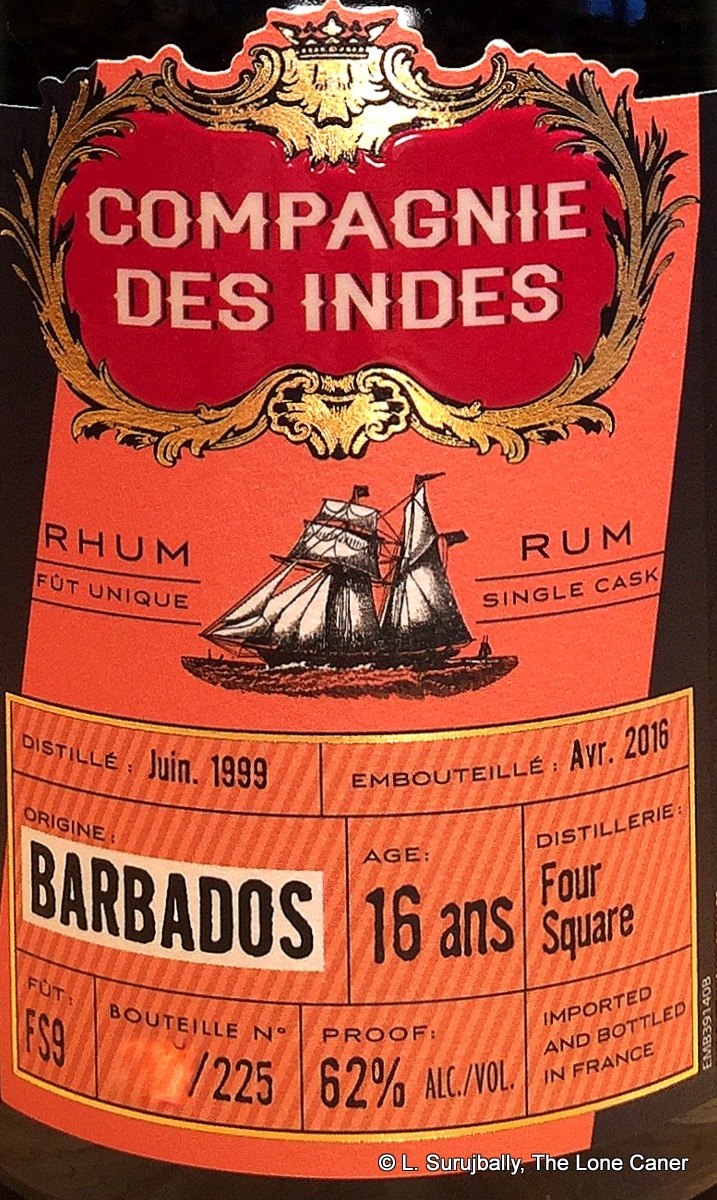

I don’t have any other observations to make, so let’s jump right in without further ado. Nose first – in a word, luscious. Although there are some salty hints to begin with, the overwhelming initial smells are of ripe black grapes, prunes, honey, and plums, with some flambeed bananas and brown sugar coming up right behind. The heat and bite of a 62% strength is very well controlled, and it presents as firm and strong without any bitchiness. After leaving it to open a few minutes, there are some fainter aromas of red/black olives, not too salty, as well as the bitter astringency of very strong black tea, and oak, mellowed by the softness of a musky caramel and vanilla, plus a sprinkling of herbs and maybe cinnamon. So quite a bit going on in there, and well worth taking one’s time with and not rushing to taste.

I don’t have any other observations to make, so let’s jump right in without further ado. Nose first – in a word, luscious. Although there are some salty hints to begin with, the overwhelming initial smells are of ripe black grapes, prunes, honey, and plums, with some flambeed bananas and brown sugar coming up right behind. The heat and bite of a 62% strength is very well controlled, and it presents as firm and strong without any bitchiness. After leaving it to open a few minutes, there are some fainter aromas of red/black olives, not too salty, as well as the bitter astringency of very strong black tea, and oak, mellowed by the softness of a musky caramel and vanilla, plus a sprinkling of herbs and maybe cinnamon. So quite a bit going on in there, and well worth taking one’s time with and not rushing to taste. We hear a lot about Damoiseau, HSE, La Favorite and Trois Rivieres on social media, while J.M. almost seems to fall into the second tier of famous names. Though not through any fault of its own – as far as I’m concerned they have every right to be included in the same breath as the others, and to many, it does.

We hear a lot about Damoiseau, HSE, La Favorite and Trois Rivieres on social media, while J.M. almost seems to fall into the second tier of famous names. Though not through any fault of its own – as far as I’m concerned they have every right to be included in the same breath as the others, and to many, it does.

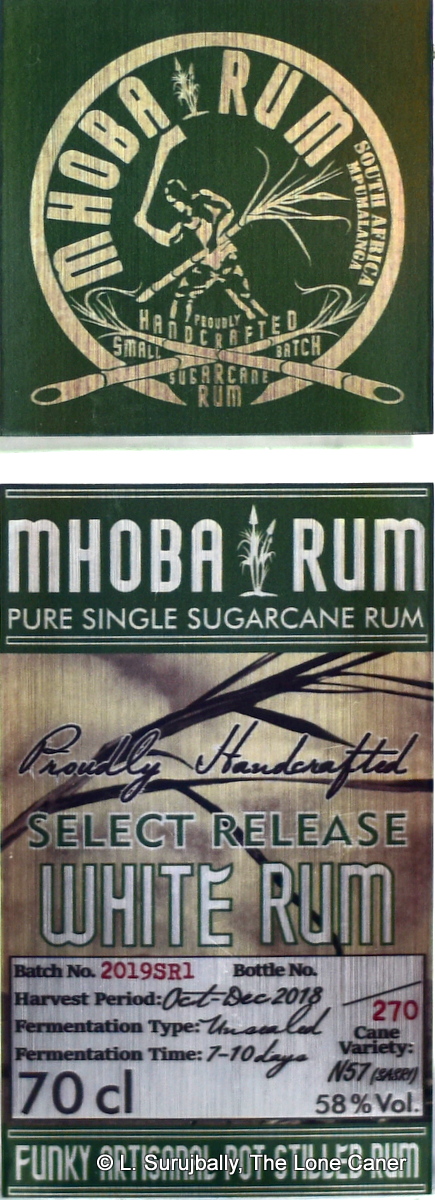

I’ll leave you to peruse Steve’s enormously informative company profile for production details (it’s really worth reading just to see what it takes to start something like a craft distillery), and just mention that the rum is pot still distilled from juice which is initially fermented naturally before boosting it with a strain of commercial yeast. The company makes three different kinds of white rums – pot still white, high ester white and a blended white, all unaged. I tried what is probably the tamest of the three, the Select, which the last one, blended from several cuts taken from batches processed between October to December of 2018 and bottled at 58%. All of this is clearly marked on the onsite-produced label (self-engraved, self-printed, manually-applied), which is one of the most informative on the market: it details batch number, date, strength, variety of cane, still, number of bottles in the run…it’s really impressive work.

I’ll leave you to peruse Steve’s enormously informative company profile for production details (it’s really worth reading just to see what it takes to start something like a craft distillery), and just mention that the rum is pot still distilled from juice which is initially fermented naturally before boosting it with a strain of commercial yeast. The company makes three different kinds of white rums – pot still white, high ester white and a blended white, all unaged. I tried what is probably the tamest of the three, the Select, which the last one, blended from several cuts taken from batches processed between October to December of 2018 and bottled at 58%. All of this is clearly marked on the onsite-produced label (self-engraved, self-printed, manually-applied), which is one of the most informative on the market: it details batch number, date, strength, variety of cane, still, number of bottles in the run…it’s really impressive work.

Could a rum tropically aged for that long be anything but a success? Certainly the comments on the

Could a rum tropically aged for that long be anything but a success? Certainly the comments on the

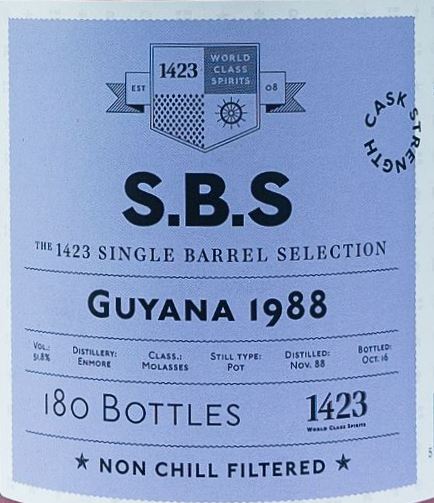

Now, there’s no doubt in my mind that this was as Guyanese as pepperpot and DDL – the real question is, which still made the rum? The label says it’s an Enmore from a pot still, all of SBS’s records (

Now, there’s no doubt in my mind that this was as Guyanese as pepperpot and DDL – the real question is, which still made the rum? The label says it’s an Enmore from a pot still, all of SBS’s records (

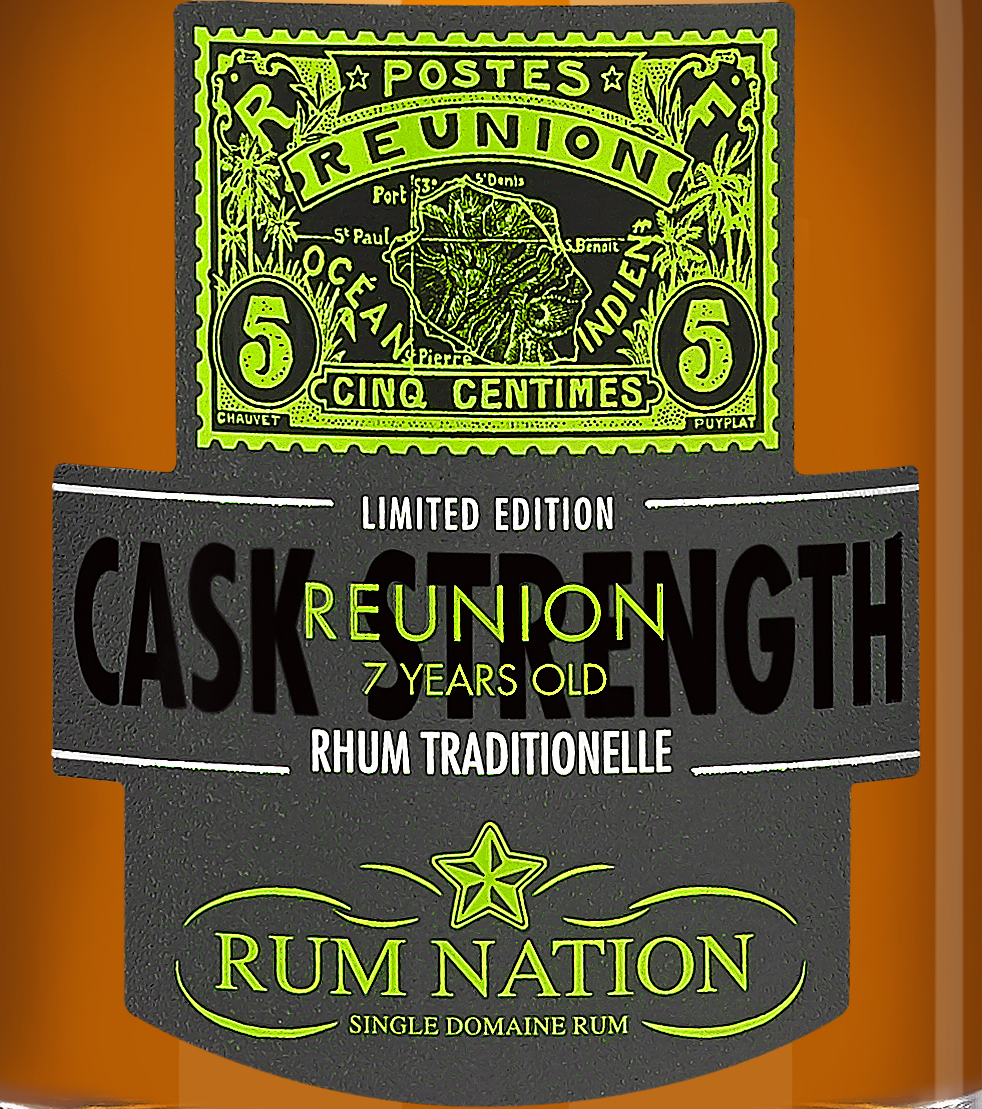

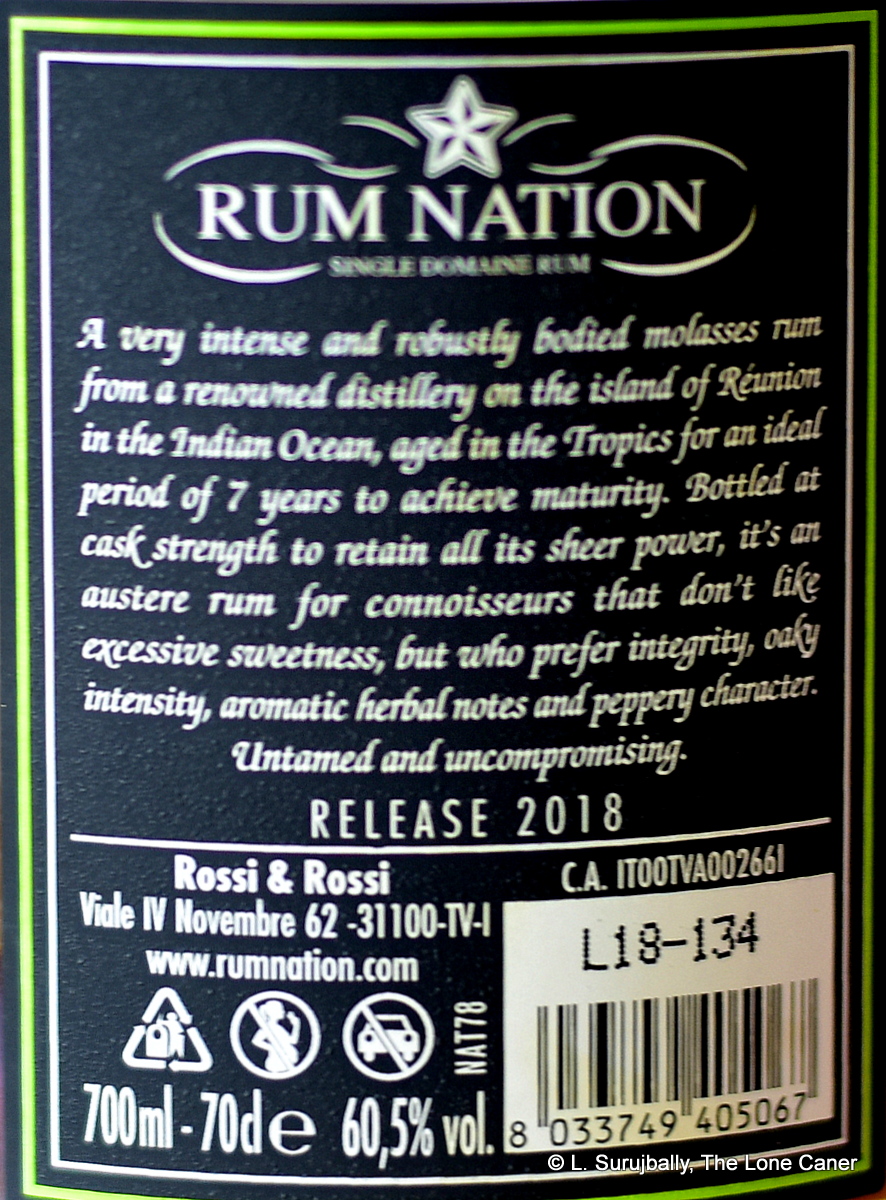

Some rums falter on the taste after opening up with a nose of uncommon quality – fortunately Rum Nation’s Réunion Cask Strength rum (to give it its full name) does not drop the ball. It’s sharp and crisp at the initial entry, mellowing out over time as one gets used to the fierce strength. It presents an interesting combination of fruitiness and muskiness and crispness, all at once – vanilla, lychee, apples, green grapes, mixing it up with ripe black cherries, yellow mangoes, lemongrass, leather, papaya; and behind all that is brine, olives, the earthy tang of a soya (easy on the vegetable soup), a twitch of wet cigarette tobacco (rather disgusting), bitter oak, and something vaguely medicinal. It’s something like a Hampden or WP, yet not — it’s too distinctively itself for that. It displays a musky tawniness, a very strong and sharp texture, with softer elements planing away the roughness of the initial attack. Somewhat over-oaked perhaps but somehow it all works really well, and the finish is similarly generous with what it provides — long and dry and spicy, with some caramel, stewed apples, green grapes, cider, balsamic vinegar, and a tannic bitterness of oak, barely contained (this may be the weakest point of the rum).

Some rums falter on the taste after opening up with a nose of uncommon quality – fortunately Rum Nation’s Réunion Cask Strength rum (to give it its full name) does not drop the ball. It’s sharp and crisp at the initial entry, mellowing out over time as one gets used to the fierce strength. It presents an interesting combination of fruitiness and muskiness and crispness, all at once – vanilla, lychee, apples, green grapes, mixing it up with ripe black cherries, yellow mangoes, lemongrass, leather, papaya; and behind all that is brine, olives, the earthy tang of a soya (easy on the vegetable soup), a twitch of wet cigarette tobacco (rather disgusting), bitter oak, and something vaguely medicinal. It’s something like a Hampden or WP, yet not — it’s too distinctively itself for that. It displays a musky tawniness, a very strong and sharp texture, with softer elements planing away the roughness of the initial attack. Somewhat over-oaked perhaps but somehow it all works really well, and the finish is similarly generous with what it provides — long and dry and spicy, with some caramel, stewed apples, green grapes, cider, balsamic vinegar, and a tannic bitterness of oak, barely contained (this may be the weakest point of the rum).

2014 was both too late and a bad year for those who started to wake up and realize that Velier’s Demerara rums were something special, because by then the positive reviews had started coming out the door, the prices began their inexorable rise, and, though we did not know it, it would mark the last issuance of any

2014 was both too late and a bad year for those who started to wake up and realize that Velier’s Demerara rums were something special, because by then the positive reviews had started coming out the door, the prices began their inexorable rise, and, though we did not know it, it would mark the last issuance of any

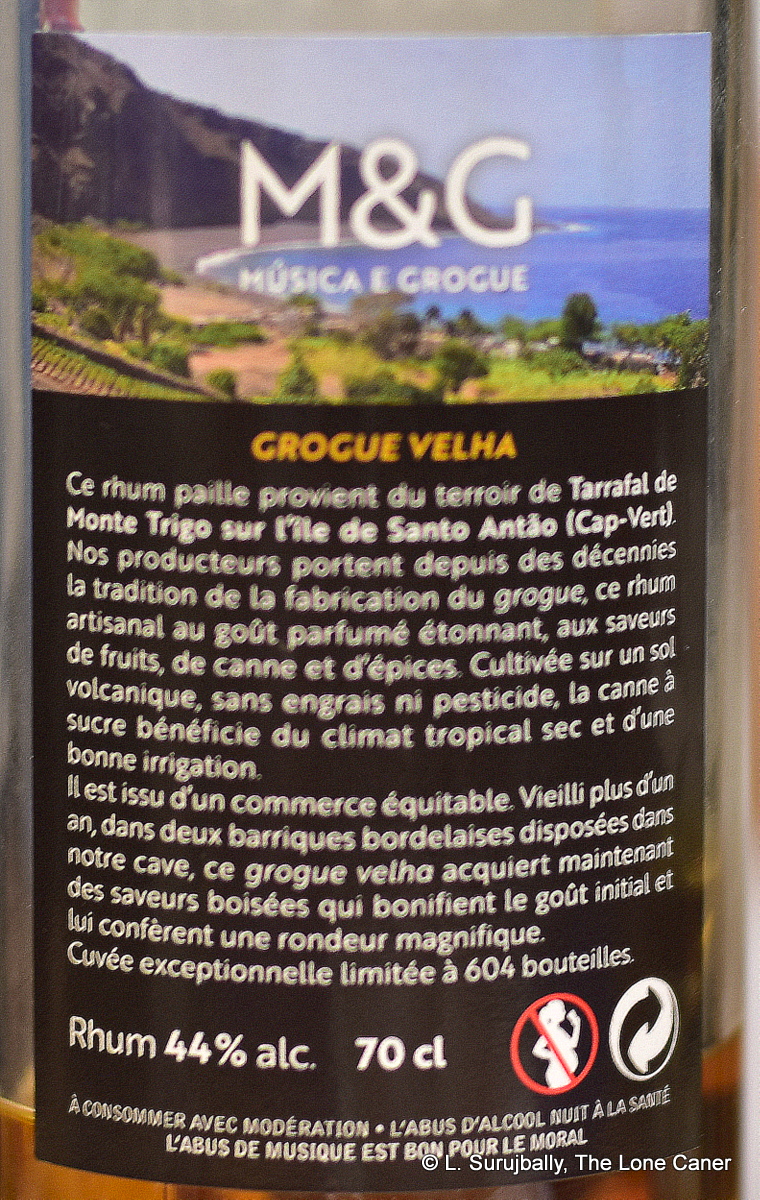

That was quite a medley on the nose, yet oddly the palate didn’t have quite have as many tunes playing. It was initially briny with those olives coming back, a little peanut brittle, salt caramel ice cream, vanilla, all held back. What I liked was its general softness and ease of delivery – there was honey and cream, set off by a touch of citrus and tannics, all in a pleasant and understated sort of combination that had a surprisingly good balance that one would not always imagine a rhum so young could keep juggling as well as it it did. Or as long. Even the finish, while simple, came together well – it gave up some short and aromatic notes, slightly woody and tannic, and balanced them out with soft fruits, pipe tobacco, coffee and vanilla, before exhaling gently on the way out. Nice.

That was quite a medley on the nose, yet oddly the palate didn’t have quite have as many tunes playing. It was initially briny with those olives coming back, a little peanut brittle, salt caramel ice cream, vanilla, all held back. What I liked was its general softness and ease of delivery – there was honey and cream, set off by a touch of citrus and tannics, all in a pleasant and understated sort of combination that had a surprisingly good balance that one would not always imagine a rhum so young could keep juggling as well as it it did. Or as long. Even the finish, while simple, came together well – it gave up some short and aromatic notes, slightly woody and tannic, and balanced them out with soft fruits, pipe tobacco, coffee and vanilla, before exhaling gently on the way out. Nice.