Photo courtesy of romhatten.dk

The El Dorado Rare Collection made its debut in early 2016 and almost immediately raised howls of protest from rum fans who felt not only that Velier had been hosed by being evicted from their state of privileged access to DDL’s store of aged barrels, but that the prices in comparison to Luca’s wares (many which had just started their inexorable climb to four figures) were out to lunch at best and extortionate at worst.

The price issue was annoying — at the time, DDL had no track record with full proof still-specific rums, or possessed anything near the kind of good will for such rums as Velier had built up over the years 2002-2014 in what I called the Age of Velier’s Demeraras; worse yet, given the disclosures about DDL’s practice of additives, to release such rums as pure without addressing the issue of dosage, and at such a high cost, simply entrenched the opinion that DDL was stealing a march on Velier and hustling to make some bucks off the full-proof, stills-as-the-killer-app trend pioneered by Luca Gargano.

It is for all those reasons that the initial rums of Release I — the PM, EHP and VSG marques, corresponding to the 12, 15 and 21 year old blends El Dorado had made famous — were received tepidly at best, though I felt they weren’t failures myself, but very decent products that just lacked Luca’s sure touch. Henrik of Rum Corner didn’t much care for the Port Mourant and discovered 14g/L of additives in the Versailles, the Fat Rum Pirate dismissed the Versailles himself while middling on the PM and loving the Enmore, and Romhatten out of Denmark, the first to review them (here, here, and here), provided an ecstatic shower of points and encomiums (perhaps because they were also selling them). Others were more muted in their praise (or condemnation), perhaps waiting to see the consensus of developing critical opinion before committing themselves.

Release II in 2017 consisted of a further Enmore and a Port Mourant, with the additional of a special Velier 70th Anniversary PM+Diamond blend. By this time most people had grudgingly resigned themselves to the reality that the Age was over and were at least happy that such Demerara rums were still being issued — and even if they did not bear the imprimatur of the Master, it was self evident that Release II corrected some of the defects of the initial bottlings, got rid of the polarizing Versailles (which takes real skill to bring to its full potential, in my opinion), and the Enmore they made that year turned out to be a spectacular rum, clocking in at 90 points in my estimation. That said, R1 and R2 didn’t really sell that well, if one judges by their continuing availability online as late as 2019.

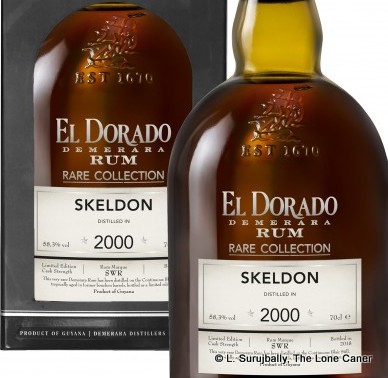

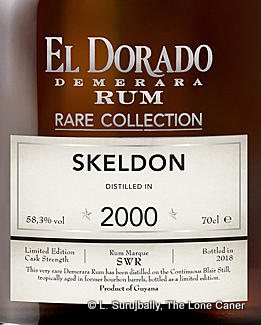

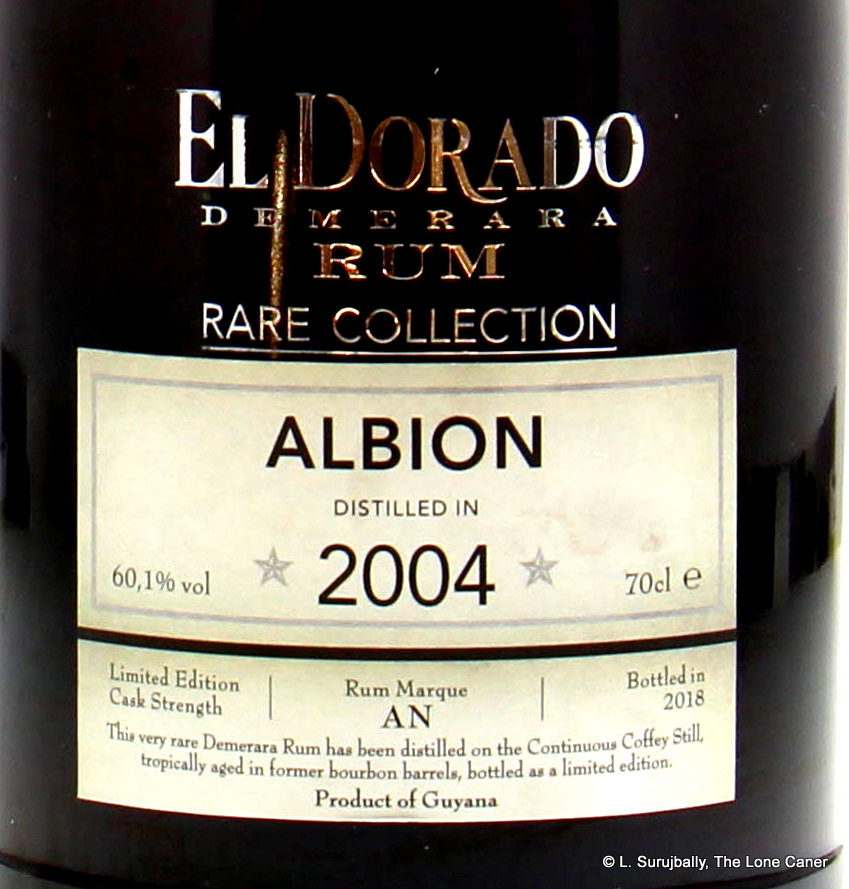

Release III was something else again. Although once more issued without fanfare or advertising (one wonders what DDL’s international brand ambassadors and marketing departments are up to, honestly), the word about R3 spread almost as swiftly as the initial news of the first bottles in 2016. This time there were four bottles – and although almost nothing has been written about the Diamond “twins” except, once again, by Romhatten (here and here), the other two elicited much more positive responses: an Albion (AN), and a Skeldon (SWR). Neither estate (I’ve been to both) has a distillery onsite any longer, since they were long dismantled and/or destroyed – but the marques are famous in their own right, especially the Skeldon, whose 1973 and 1978 Velier editions remain Grail quests for many.

Speaking for myself, I’d have to say that with the Third Release, DDL has put to rest any doubts as to the legitimacy of the Rare Collection being excellent rums in their own right. They’re damned fine rums, the ones I’ve tried, up to the level of the RII Enmore 1996. I can’t tell whether the R1 series will ever become collector’s prized pieces or sought-after grail quests the way the original Veliers have become – but they’re good and worth finding. Note that they remain, not just in my opinion, overpriced and this may account for their continuing availability.

Speaking for myself, I’d have to say that with the Third Release, DDL has put to rest any doubts as to the legitimacy of the Rare Collection being excellent rums in their own right. They’re damned fine rums, the ones I’ve tried, up to the level of the RII Enmore 1996. I can’t tell whether the R1 series will ever become collector’s prized pieces or sought-after grail quests the way the original Veliers have become – but they’re good and worth finding. Note that they remain, not just in my opinion, overpriced and this may account for their continuing availability.

It’s almost a movie trope that horror movies first exist as true horror that scare the crap out of everyone, devolve into lesser boo-fests, and end up in sad comedies and unworthy money-grab rip-offs as the franchise passes its sell-by date. I don’t think the Rares will end up this way, because DDL has made it known that they will no longer export bulk rum from the wooden stills, instead holding on to them for their own special releases and blends…so, clearly they are betting on still-specific rum into the future – though perhaps not always at cask strength. The 15 year old wine finished series and its companion 12 year old set, the new Master Distiller’s collection at standard strength which showcase the stills, all point in this direction.

And this is a good thing, as the stills DDL is so fortunate to possess are unique and they make fantastic rums when used right, and with skill. One can only hope the pricing starts to be more reasonable in the years to come, because right now it’s too early to call them must-haves, and with the cost of them, they might not get the audience that would make them so. They are certainly better than the vastly overpriced 15YO and 12 YO wine-finished rums at standard strength.

Update (2019)

Will the Rares survive? In late 2019, four colour-coded bottles which were specifically not Rare Collection items, began to gather some attention online:

Will the Rares survive? In late 2019, four colour-coded bottles which were specifically not Rare Collection items, began to gather some attention online:

- PM/Uitvlugt/Diamond 2010 9YO at 49.6% (violet),

- Port Mourant/Uitvlugt 2010 9YO at 51% (orange),

- Uitvlugt/Enmore 2008 11YO 47.4% (blue)

- Diamond/Port Mourant 2010 9YO at 49.1% (teal).

None of these were specific to a still, and each was priced at €179 in the single online shop in online where they are to be found. All were blends (aged as such in the barrel, not mixed post-ageing), and all sported some reasonable tropical years. It is unclear whether they are meant to supplement the single-still ethos of the super-specific Rares, or supplant them. As of this writing I have yet to taste them myself, though I do own them.

Whatever the case, DDL certainly has taken the indie movement seriously and seen the potential of what the Age demonstrated – one can just hope their pricing system starts to show more tolerance for the skinny purses of most of us, otherwise they’ll be shared among aficionados rather than bought for their own sake. And there they’ll remain, on the dusty shelves of small stores, looked at and admired, perhaps, but not often purchased. One can still occasionally see them pop up on Rum Auctioneer or other auction sites.

Update (2023)

By 2023 an interesting new development was clearly visible: DDL had discarded the Rares entirely, and moved away from these colour coded experimentals. What they did was start issuing special 15 YO and other aged editions, in two specific flavours: one, released at standard strength of 40%, that showcased the famed stills (I think these were mostly like the inauguaral 2006 edition released in 2021); and two, a cask strength aged series — this could be a blend, possibly including a finish or special cask ageing regiment, a special edition of some kind not always tied to an age or a still, or a year-specific one, and sometimes made for large spirits shops (like Wine & Beyond in Calgary). The key point to note is that they have folded this into the regular El Dorado range of rums – same bottle and general label design. This is, in my opinion, a smart move, since it does away with the recognition factor and plays to DDL’s global brand awareness. So far I know of the following releases, none of which I have written about as of this writing:

Type 1 Standard Strength

- 2006-2021 15 YO 40% Port Mourant (PM)

- 2006-2021 15 YO 40% Enmore

- 2006-2021 15 YO 40% Versailles (VSG)

- 2009-2021 12 YO 40% Port Mourant (PM)

- 2009-2021 12 YO 40% Versailles (VSG)

- 2009-2021 12 YO 40% Enmore

Type 2 Cask Strength

- 1998-2022 24YO 50.3% PM/Enmore “The Last Casks Collection – Black”

- 1998-2022 24YO 49.1% Diamond “The Last Casks Collection – Red”

- 2000-2022 22YO 54.4% Diamond “The Last Casks Collection – Gold”

- 2003-2018 15YO 62.3% Enmore Sauternes Finish

- 2005-2021 16 YO 55.3% Blend with White Port Cask Finish

- 2005-2021 16 YO 55.1% Versailles Madeira Dry Casks

- 2006-2021 15 YO 57.3% Blend with Madeira Sweet Cask Finish

- 2006-2022 16 YO 47.1% PM-Savalle Blend, Wine & Beyond Single Barrel (Canada only)

- 2009-2021 12YO 54.3% Enmore (EHP)

- 2009-2021 12 YO 56.7% Port Mourant (PM)

- 2012-2022 10 YO 58.4% PM-Savalle-Diamond Blend, Wine & Beyond Single Barrel (Canada only)

The Rare Collection Rums

I have been fortunate enough to buy and review many of the Collection so far, and for those who wish to get into the specifics, the reviews are linked here:

- El Dorado Rare Collection R1 – Enmore 1993-2015 22 YO EHP (86)

- El Dorado Rare Collection R1 – Port Mourant 1999-2015 16 YO PM (83)

- El Dorado Rare Collection R1 – Versailles 2002-2015 13 YO VSG (84.5)

- El Dorado Rare Collection R2 – Enmore 1996-2017 20YO EHP (90)

- El Dorado Rare Collection R2 – Port Mourant 1997-2017 20 YO PM (86.5)

- El Dorado Rare Collection R2 – PM +Diamond 2001-2017 16 YO PM+SVW (87)

- El Dorado Rare Collection R3 – Albion 2004-2018 14 YO AN (88)

- El Dorado Rare Collection R3 – Skeldon 2000-2018 18 YO SWR (87)

- El Dorado Rare Collection R3 – Diamond 1998-2018 20 YO <SWR> DLR (55.1%)

- El Dorado Rare Collection R3 – Diamond 1998-2018 20 YO <SWR> DLR (54.9%)

In January 2021, the UK based NW Rum Club did a complete review of the entire Rare Collection (releases I, II and III), and it’s worth a look, very informative, talking about the releases, and the stills. In 2023 Stuart of the Secret Rum Bar, also in the UK, did the same thing.

The French-bottled, Australian-distilled Beenleigh 5 Year Old Rum is a screamer of a rum, a rum that wasn’t just released in 2018, but unleashed. Like a mad roller coaster, it careneed madly up and down and from side to side, breaking every rule and always seeming just about to go off the rails of taste before managing to stay on course, providing, at end, an experience that was shattering — if not precisely outstanding.

The French-bottled, Australian-distilled Beenleigh 5 Year Old Rum is a screamer of a rum, a rum that wasn’t just released in 2018, but unleashed. Like a mad roller coaster, it careneed madly up and down and from side to side, breaking every rule and always seeming just about to go off the rails of taste before managing to stay on course, providing, at end, an experience that was shattering — if not precisely outstanding. I still remember how unusual the

I still remember how unusual the

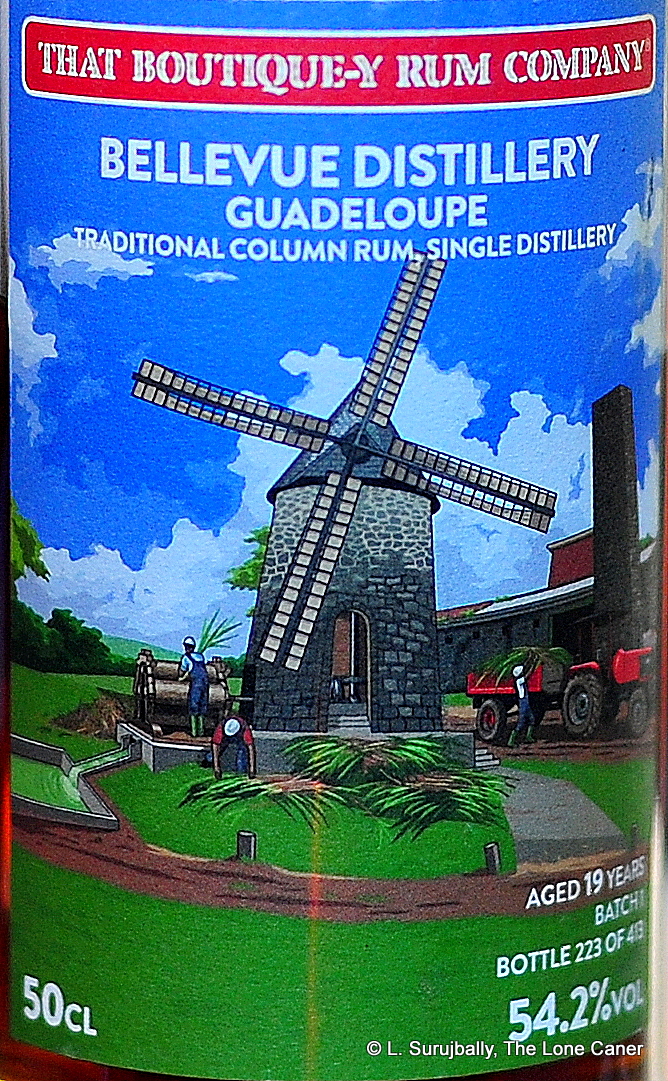

Take this one, which proves that TBRC has a knack for ferreting out good barrels. It’s not often you find a rum that is from the French West Indies aged beyond ten years — Neisson’s been making a splash recently with its 18 YO, you might recall, for that precise reason. To find one that’s a year older from Guadeloupe in the same year is quite a prize and I’ll just mention it’s 54.2%, aged seven years in Guadeloupe and a further twelve in the UK, and outturn is 413 bottles. On stats alone it’s the sort of thing that makes my glass twitch.

Take this one, which proves that TBRC has a knack for ferreting out good barrels. It’s not often you find a rum that is from the French West Indies aged beyond ten years — Neisson’s been making a splash recently with its 18 YO, you might recall, for that precise reason. To find one that’s a year older from Guadeloupe in the same year is quite a prize and I’ll just mention it’s 54.2%, aged seven years in Guadeloupe and a further twelve in the UK, and outturn is 413 bottles. On stats alone it’s the sort of thing that makes my glass twitch. Guadeloupe rums in general lack something of the fierce and stern AOC specificity that so distinguishes Martinique, but they’re close in quality in their own way, they’re always good, and frankly, there’s something about the relative voluptuousness of a Guadeloupe rhum that I’ve always liked. Peter sold me on the quality of the

Guadeloupe rums in general lack something of the fierce and stern AOC specificity that so distinguishes Martinique, but they’re close in quality in their own way, they’re always good, and frankly, there’s something about the relative voluptuousness of a Guadeloupe rhum that I’ve always liked. Peter sold me on the quality of the

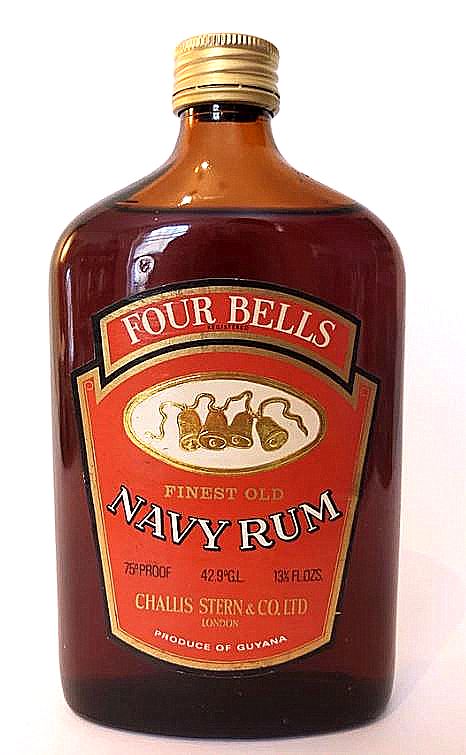

Nose – Quite a bit different from the strongly focussed Demerara profile of the Navy 70º we looked at before – had the label not been clear what was in it, I would have not guessed there was any Jamaican in here. The wooden stills profile of Guyana is tamed, and the aromas are prunes, licorice, black grapes and a light brininess. After a while some salt caramel ice cream, nougat, toffee and anise become more evident. Sharp fruits are held way back and given the absence of any kind of tarriness, I’d hazard that Angostura provided the Trinidadian component.

Nose – Quite a bit different from the strongly focussed Demerara profile of the Navy 70º we looked at before – had the label not been clear what was in it, I would have not guessed there was any Jamaican in here. The wooden stills profile of Guyana is tamed, and the aromas are prunes, licorice, black grapes and a light brininess. After a while some salt caramel ice cream, nougat, toffee and anise become more evident. Sharp fruits are held way back and given the absence of any kind of tarriness, I’d hazard that Angostura provided the Trinidadian component.

Its standout aspect was how smooth it came across when tasted. As with the Albion we looked at before, the rum didn’t profile like anywhere near its true strength, was warm and firm and tasty, trending a bit towards being over-oaked and ever-so-slightly too tannic. But those powerful notes of unsweetened cooking chocolate, creme brulee, caramel, dulce de leche, molasses and cumin mitigated the wooden bite and provided a solid counterpoint into which subtler marzipan and mint-chocolate hints could be occasionally noticed, flitting quietly in and out. The finish continued these aspects while gradually fading out, and with some patience and concentration, port-flavoured tobacco, brown sugar and cumin could be discerned.

Its standout aspect was how smooth it came across when tasted. As with the Albion we looked at before, the rum didn’t profile like anywhere near its true strength, was warm and firm and tasty, trending a bit towards being over-oaked and ever-so-slightly too tannic. But those powerful notes of unsweetened cooking chocolate, creme brulee, caramel, dulce de leche, molasses and cumin mitigated the wooden bite and provided a solid counterpoint into which subtler marzipan and mint-chocolate hints could be occasionally noticed, flitting quietly in and out. The finish continued these aspects while gradually fading out, and with some patience and concentration, port-flavoured tobacco, brown sugar and cumin could be discerned.

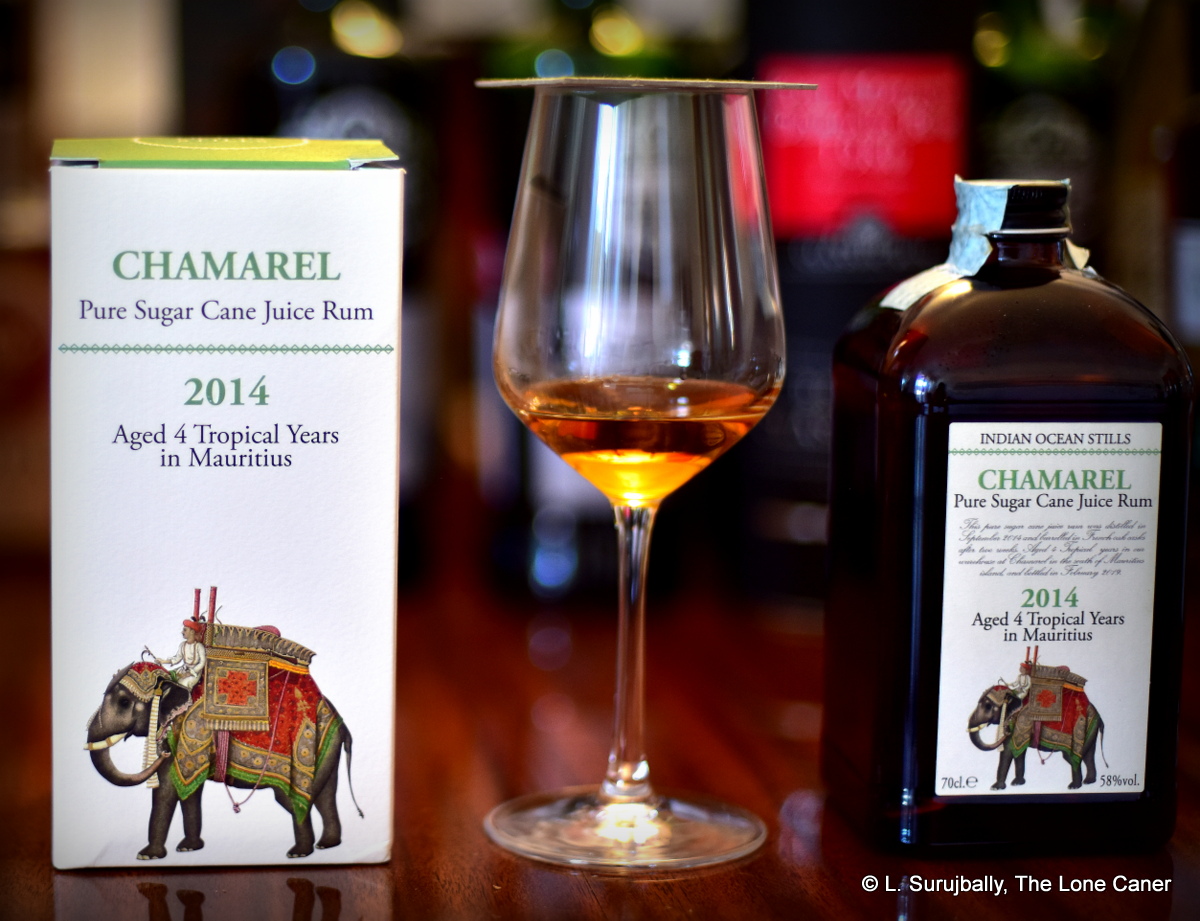

Brief stats: a 4 year old rum distilled in September 2014, aged in situ in French oak casks and bottled in February 2019 at a strength of 58% ABV. Love the labelling and it’s sure to be a fascinating experience not just because of the selection by Velier, or its location (we have tried few rums from there though those

Brief stats: a 4 year old rum distilled in September 2014, aged in situ in French oak casks and bottled in February 2019 at a strength of 58% ABV. Love the labelling and it’s sure to be a fascinating experience not just because of the selection by Velier, or its location (we have tried few rums from there though those  Rumaniacs Review #107 | R-0688

Rumaniacs Review #107 | R-0688 Palate – Waiting for this to open up is definitely the way to go, because with some patience, the bags of funk, soda pop, nail polish, red and yellow overripe fruits, grapes and raisins just become a taste avalanche across the tongue. It’s a very solid series of tastes, firm but not sharp unless you gulp it (not recommended) and once you get used to it, it settles down well to just providing every smidgen of taste of which it is capable.

Palate – Waiting for this to open up is definitely the way to go, because with some patience, the bags of funk, soda pop, nail polish, red and yellow overripe fruits, grapes and raisins just become a taste avalanche across the tongue. It’s a very solid series of tastes, firm but not sharp unless you gulp it (not recommended) and once you get used to it, it settles down well to just providing every smidgen of taste of which it is capable.

If we accept these data points, then of course the Casino is not, by all current definitions, a rum, and in point of fact, the entry might just as easily be listed in the Rumaniacs page since this version is no longer being made — the word “rum” was either replaced by “room” or dropped completely from the label when Hungary joined the EU in 2004, and that suggests a manufacture for the product I tasted of around 1988-2003 which actually makes it a heritage rum entry, but what the hell.

If we accept these data points, then of course the Casino is not, by all current definitions, a rum, and in point of fact, the entry might just as easily be listed in the Rumaniacs page since this version is no longer being made — the word “rum” was either replaced by “room” or dropped completely from the label when Hungary joined the EU in 2004, and that suggests a manufacture for the product I tasted of around 1988-2003 which actually makes it a heritage rum entry, but what the hell.

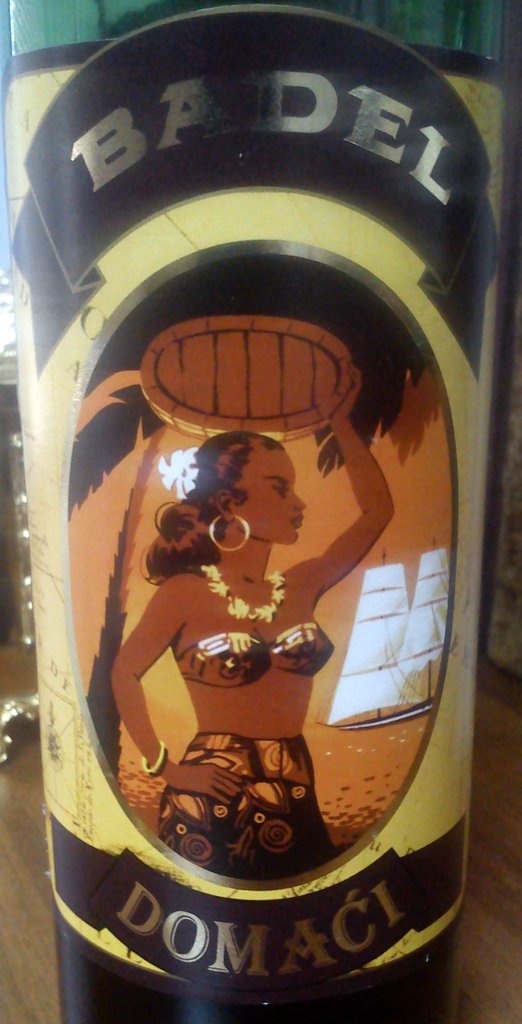

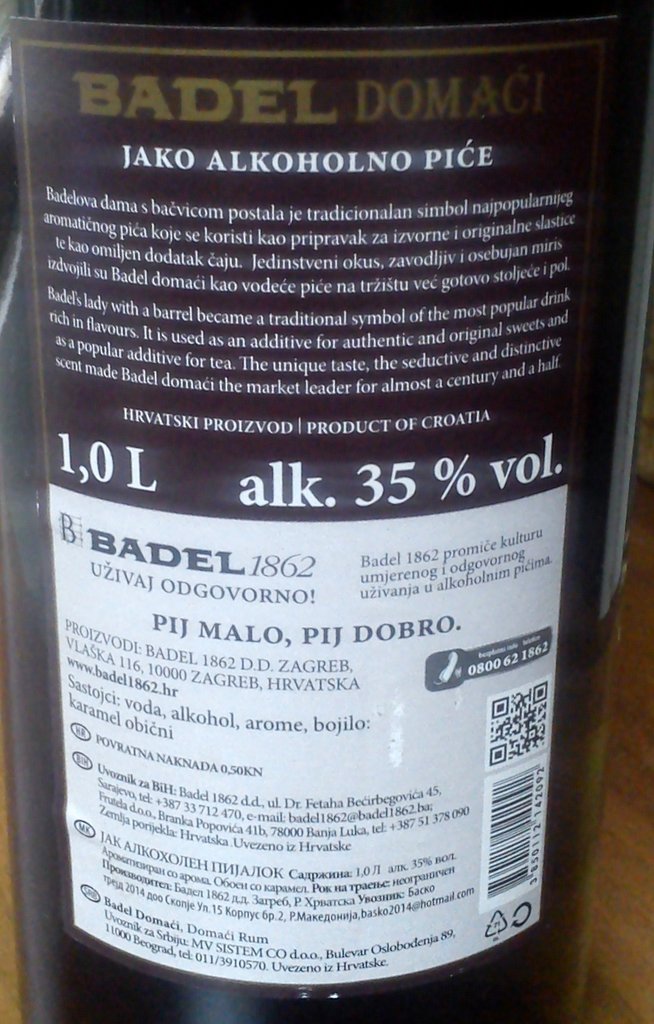

Unsurprisingly it’s mostly for sale in the Balkans — Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia, with outliers in Germany — and has made exactly zero impact on the greater rum drinking public in the West. Wes briefly touched on it with a review of

Unsurprisingly it’s mostly for sale in the Balkans — Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia, with outliers in Germany — and has made exactly zero impact on the greater rum drinking public in the West. Wes briefly touched on it with a review of

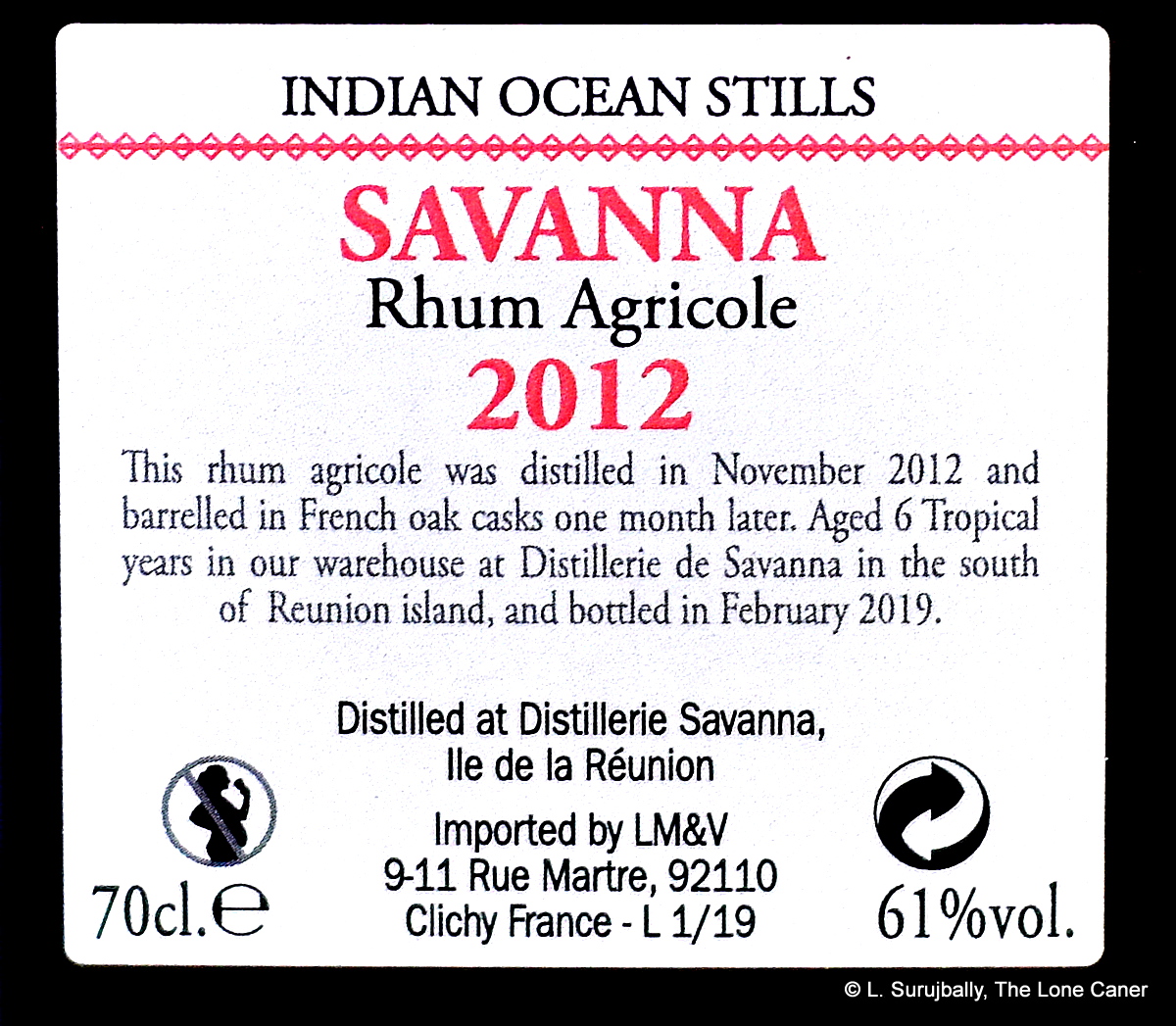

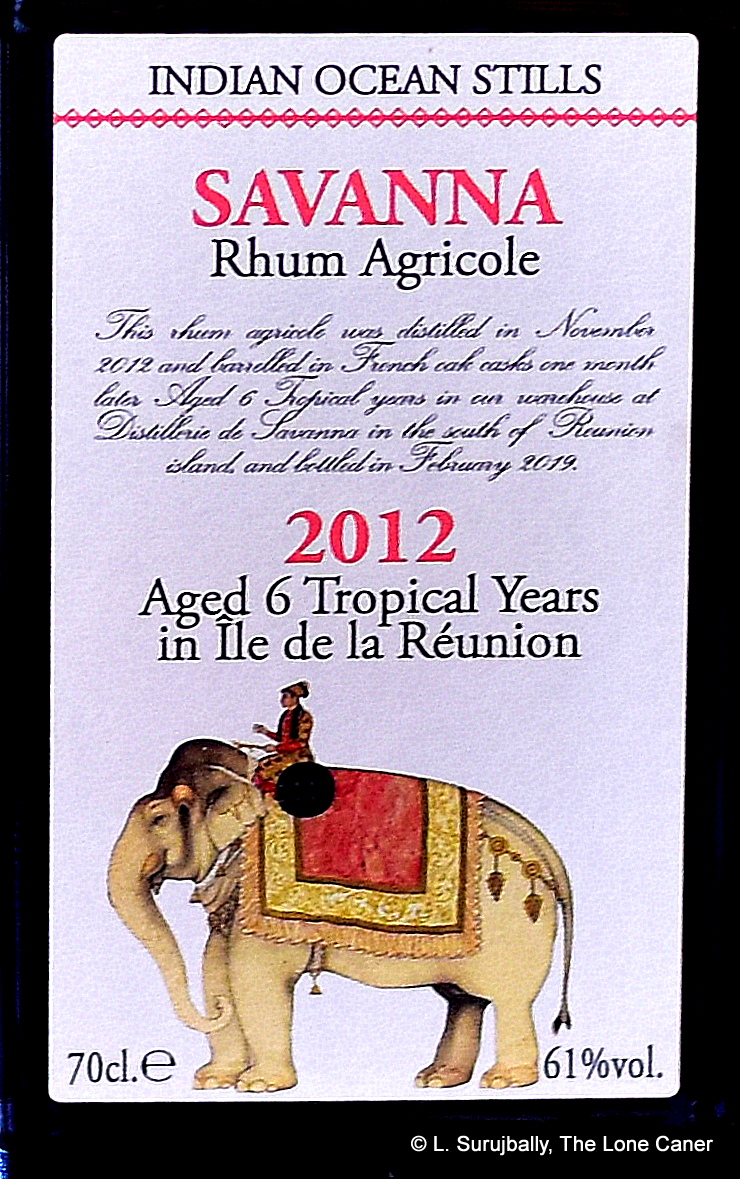

The “Indian Ocean Still” series of rums have a labelling concept somewhat different from the stark wealth of detail that usually accompanies a Velier collaboration. Personally, I find it very attractive from an artistic point of view – I love the man riding on the elephant motif of this and the companion

The “Indian Ocean Still” series of rums have a labelling concept somewhat different from the stark wealth of detail that usually accompanies a Velier collaboration. Personally, I find it very attractive from an artistic point of view – I love the man riding on the elephant motif of this and the companion  Man, this was a really good dram. It adhered to most of the tasting points of a true agricole — grassiness, crisp herbs, citrus, that kind of thing — without being slavish about it. It took a sideways turn here or there that made it quite distinct from most other agricoles I’ve tried. If I had to classify it, I’d say it was like a cross between the fruity silkiness of a St. James and the salt-oily notes of a Neisson.

Man, this was a really good dram. It adhered to most of the tasting points of a true agricole — grassiness, crisp herbs, citrus, that kind of thing — without being slavish about it. It took a sideways turn here or there that made it quite distinct from most other agricoles I’ve tried. If I had to classify it, I’d say it was like a cross between the fruity silkiness of a St. James and the salt-oily notes of a Neisson.

The rum was standard strength (40%), so it came as little surprise that the palate was very light, verging on airy – one burp and it was gone forever. Faintly sweet, smooth, warm, vaguely fruity, and again those minerally metallic notes could be sensed, reminding me of an empty tin can that once held peaches in syrup and had been left to dry. Further notes of vanilla, a single cherry and that was that, closing up shop with a finish that breathed once and died on the floor. No, really, that was it.

The rum was standard strength (40%), so it came as little surprise that the palate was very light, verging on airy – one burp and it was gone forever. Faintly sweet, smooth, warm, vaguely fruity, and again those minerally metallic notes could be sensed, reminding me of an empty tin can that once held peaches in syrup and had been left to dry. Further notes of vanilla, a single cherry and that was that, closing up shop with a finish that breathed once and died on the floor. No, really, that was it.

Next word: “Black”. Baby Rum Jesus help us. Long discredited as a way to classify rum, and if you are curious as to why, I refer you to

Next word: “Black”. Baby Rum Jesus help us. Long discredited as a way to classify rum, and if you are curious as to why, I refer you to

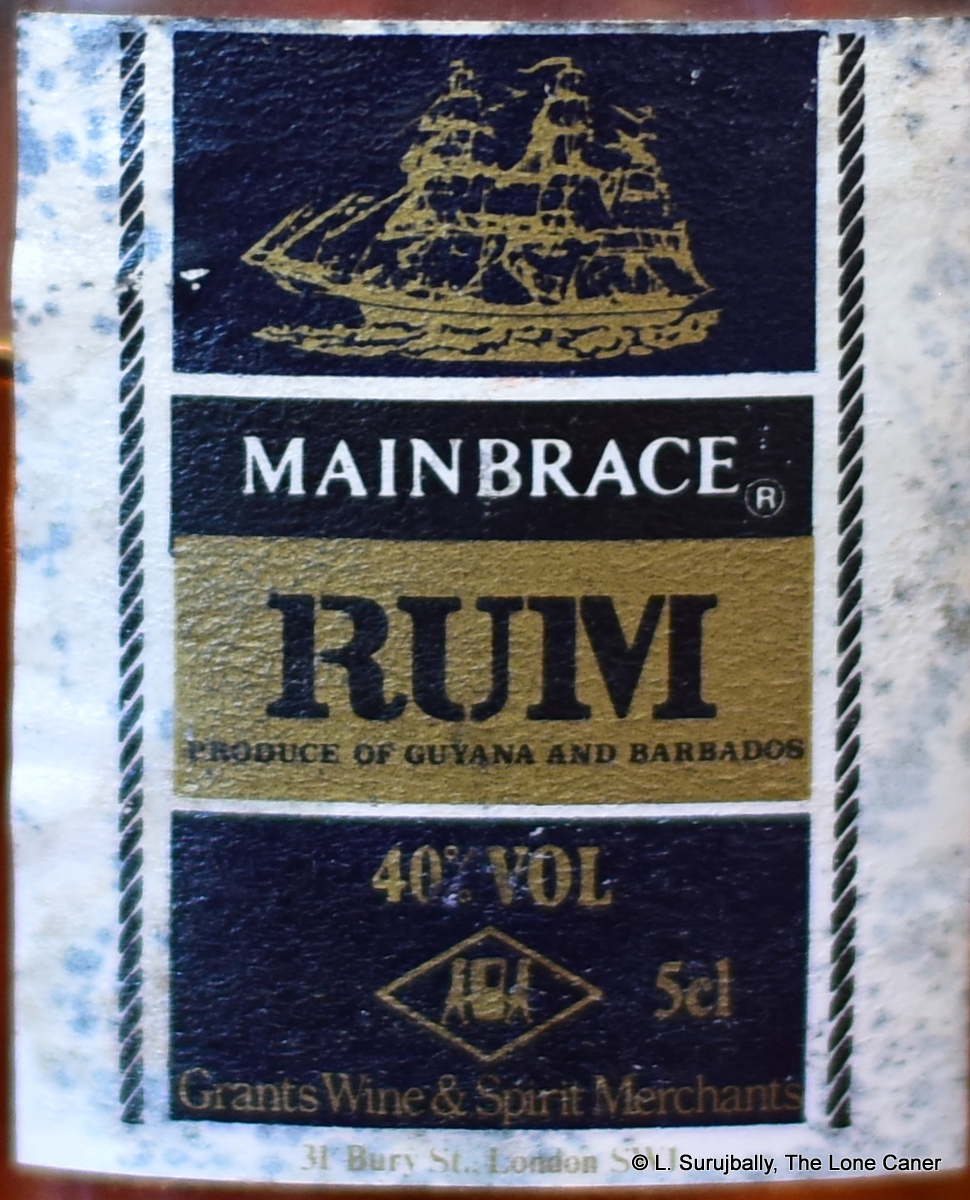

The “Guyana” spelling sets a lower post-independence date of 1966. Grants also released a Navy Rum and a Demerara Rum – both from Guyana, and both at “70º proof”. The address is written differently on their labels though, being “Grants of Saint James” on the Demerara label (Bury Lane is in the area of St. James, and a stone’s throw away from St. James’s Street…and BBR). Grants was still referring to itself as “of St. James” first (and until 1976 at least), but I think it’s the 40% ABV that’s key here, since that only came into effect in the mid 1980s in the UK.

The “Guyana” spelling sets a lower post-independence date of 1966. Grants also released a Navy Rum and a Demerara Rum – both from Guyana, and both at “70º proof”. The address is written differently on their labels though, being “Grants of Saint James” on the Demerara label (Bury Lane is in the area of St. James, and a stone’s throw away from St. James’s Street…and BBR). Grants was still referring to itself as “of St. James” first (and until 1976 at least), but I think it’s the 40% ABV that’s key here, since that only came into effect in the mid 1980s in the UK.

Whatever the case, the rum was as fierce as the Diamond, and even at a microscopically lower proof, it took no prisoners. It exploded right out of the glass with sharp, hot, violent aromas of tequila, rubber, salt, herbs and really good olive oil. If you blinked you could see it boiling. It swayed between sweet and salt, between soya, sugar water, squash, watermelon, papaya and the tartness of hard yellow mangoes, and to be honest, it felt like I was sniffing a bottle shaped mass of whup-ass (the sort of thing Guyanese call “regular”).

Whatever the case, the rum was as fierce as the Diamond, and even at a microscopically lower proof, it took no prisoners. It exploded right out of the glass with sharp, hot, violent aromas of tequila, rubber, salt, herbs and really good olive oil. If you blinked you could see it boiling. It swayed between sweet and salt, between soya, sugar water, squash, watermelon, papaya and the tartness of hard yellow mangoes, and to be honest, it felt like I was sniffing a bottle shaped mass of whup-ass (the sort of thing Guyanese call “regular”). Rumaniacs Review #105 | 0678

Rumaniacs Review #105 | 0678 Nose – A combination of the

Nose – A combination of the  Rumaniacs Review #104 | 0677

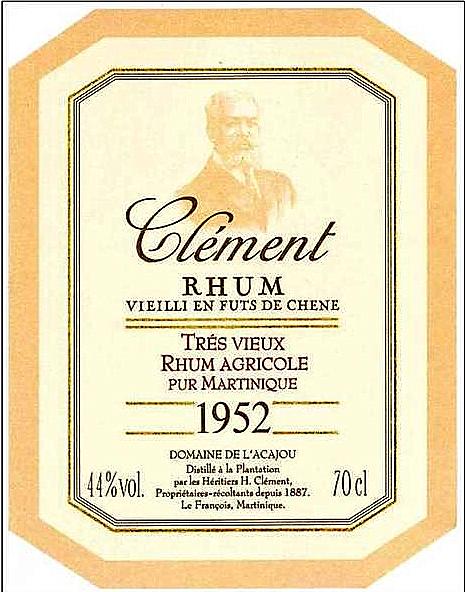

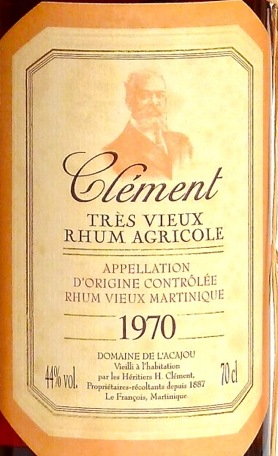

Rumaniacs Review #104 | 0677 Another peculiarity of the rhum is the “AOC” on the label. Since the AOC came into effect only in 1996, and even at its oldest this rhum was done ageing in 1991, how did that happen? Cyril told me it had been validated by the AOC after it was finalized, which makes sense (and probably applies to the 1976 edition as well), but then, was there a pre-1996 edition with one label and a post-1996 edition with another one? (the two different boxes it comes in suggests the possibility). Or, was the entire 1970 vintage aged to 1991, then held in inert containers (or bottled) and left to gather dust for some reason? Is either 1991 or 1985 even real? — after all, it’s entirely possible that the trio (of 1976, 1970 and 1952, whose labels are all alike) was released as a special millesime series in the late 1990s / early 2000s. Which brings us back to the original question – how old is the rhum?

Another peculiarity of the rhum is the “AOC” on the label. Since the AOC came into effect only in 1996, and even at its oldest this rhum was done ageing in 1991, how did that happen? Cyril told me it had been validated by the AOC after it was finalized, which makes sense (and probably applies to the 1976 edition as well), but then, was there a pre-1996 edition with one label and a post-1996 edition with another one? (the two different boxes it comes in suggests the possibility). Or, was the entire 1970 vintage aged to 1991, then held in inert containers (or bottled) and left to gather dust for some reason? Is either 1991 or 1985 even real? — after all, it’s entirely possible that the trio (of 1976, 1970 and 1952, whose labels are all alike) was released as a special millesime series in the late 1990s / early 2000s. Which brings us back to the original question – how old is the rhum?