William Hinton from Madeira is not a name to conjure with in the annals of rum, but this is not the first time they have come up for mention – their distillery produced the Engenho Novo da Madeira rum that Rum Nation released with some fanfare back in 2017. The following year the company of Engenho Novo, Hinton’s new incarnation (and not to be confused with Engenhos do Norte, producer of the “970 Agricola”) released some rums for themselves, and we’ll be looking at these over the next week or so.

William Hinton from Madeira is not a name to conjure with in the annals of rum, but this is not the first time they have come up for mention – their distillery produced the Engenho Novo da Madeira rum that Rum Nation released with some fanfare back in 2017. The following year the company of Engenho Novo, Hinton’s new incarnation (and not to be confused with Engenhos do Norte, producer of the “970 Agricola”) released some rums for themselves, and we’ll be looking at these over the next week or so.

Hinton classify their rums into three tiers: (1) the exclusive single casks, which are blends of 6YO “new Hinton” rums and 25 YO “old Hinton” rums from before the shutdown in 1986 (see below) which are then finished in various other barrels like wine or whisky or what have you; (2) the premium range which consists of two rums, an award winning 6 YO and a high proof white; and (3) the bartenders’ mixes, for general audiences, which their website refers to, in an odd turn of phrase, as a “service rum.” One of that final category is the white rum we’re examining today.

The white is a cane juice agricole – a term which Madeira has a right to use – but it is not unaged. While the site does not specifically say so, I was told it’s under a year, around six months, in French oak casks 1. It is bottled at 40%, column still, so nothing “serious”. It’s made fit for purpose, that’s all.

Unfortunately that purpose seems to be to put me to sleep. Dare I say it is underwhelming? It is a soft and extremely light white rum with very little in the way of an aromas at all. It’s delicate, flowery and admittedly very clean – and one has to seriously pay attention to make out some flowers, dill, herbs, grass, sugar water and wet moss (!!), before it disappears like a summer zephyr you barely sensed in the first place

The palate is better, and remains light and clean. It has a queer sort of dusty aroma to it, like old library books stored in long disused storage room. That gradually goes away and is replaced with a dry taste of cheerios, and some fruits. Almonds and a curiously faint whiff of vanilla. I read somewhere that this white is made to service a poncha — a very old cocktail from Portugal’s great seafaring days invented to combat scurvy (rum plus sugar plus lemon juice, and some honey) — not so much to replace Bacardi Superior … though you could not imagine them being displeased if it did. Drinking it neat is probably a nonstarter since it’s so wispy, and of course there’s not much of a finish (at 40% I wasn’t looking for one). Briefly fruity and floral, a quick whiff of herbs, and it’s gone.

Although it has some very brief tastes and aromas that I suppose derive from the minimal ageing (before the results of that process got filtered right back out again), the white displays little that would make it stand out. In fact, while demonstrably being an agricole, it hardly tastes like one at all. It’s what I’m beginning to refer to more and more often as a “cruise-ship white”, a kind of all-encompassing milquetoast rum whose every character has been bleached and out so its only remaining function is to deliver a shot of bland alcohol (like, say, vodka) into a mixed drink for those who don’t know or don’t care (or both).

Although it has some very brief tastes and aromas that I suppose derive from the minimal ageing (before the results of that process got filtered right back out again), the white displays little that would make it stand out. In fact, while demonstrably being an agricole, it hardly tastes like one at all. It’s what I’m beginning to refer to more and more often as a “cruise-ship white”, a kind of all-encompassing milquetoast rum whose every character has been bleached and out so its only remaining function is to deliver a shot of bland alcohol (like, say, vodka) into a mixed drink for those who don’t know or don’t care (or both).

That said, honesty compels me to admit that there was some interesting stuff in the wings, sensed but not seen, a trace only, perhaps only waiting to emerge at the proper time, but alas, not enough to save it. The premium series probably address such deficiencies, and if so, it was a smart move to separate the generalized cocktail fodder (which this is) from a more upscale and dangerous version aimed at more masochistic folks who’ll try anything once. If you want to know the real potential of Hinton’s white rum, don’t stop and waste time dawdling with this one, go straight for the 69% and be prepared to have your socks blown off. Unless you like soft and easy whites, I’d walk away from this one.

(#829)(75/100)

Background & History

It’s long been noted that sugar cane migrated from Indonesia to India to the Mediterranean, and continued its westward march by being cultivated on Madeira by the first half of the 15th century. From there it jumped to the New World, but sugar remained a stable and very profitable cash crop in Madeira and the primary engine of the island’s economy for two hundred years. At that point, with Brazil and other Portuguese colonies becoming the main sources of sugar, the focus of Madeira switched to wine, for which it became renowned (sugar cane production continued, just at a reduced level).

The British took some involvement in the island in the 1800s, which led to several inflows of their citizens, some of whom stayed – one of these was William Hinton, a businessman who arrived in 1838 and started the eponymous company seven years later. First a sugar factory was constructed and a distillery was added — these were large and technologically advanced and allowed Engenho Hinton to become the largest sugar processor on the island, as well as the largest rum maker (though I’m not sure what rums they actually did produce) by the 1920s.

Unfortunately, by the 1970s and 1980s as sugar production became more and more industrialized and global, more cheaply produced sugar from Brazil and India and elsewhere cut into Hinton’s sales (they were part of a regulated EEC industry, so low-cost labour was not an option), and by 1986 the factory and distillery closed and the facilities were mothballed – the website gives no reasons for the closure, so I’m making an educated guess here, as well as assuming they did not sell off or otherwise dispose of what bean counters like me like to refer to as “plant”.

It was restarted by Hinton’s heirs in 2006 as Engenho Novo de Madeira with a column still and using Madeira sugar cane: here again there is scanty information on where this sugar cane comes from, their own property or bought from others. Whatever the source, the practice of using rendered sugar cane juice (”honey”) continued and notes from a brochure I have state that the column still was one restored in 1969 and again in 2007, suggesting that when the distillery closed, its equipment remained intact and in place.

La Rhumerie de Chamarel, that Mauritius outfit we last saw when I reviewed their 44% pot-still white, doesn’t sit on its laurels with a self satisfied smirk and think it has achieved something. Not at all. In point of fact it has a couple more whites, both cane juice derived and distilled on their

La Rhumerie de Chamarel, that Mauritius outfit we last saw when I reviewed their 44% pot-still white, doesn’t sit on its laurels with a self satisfied smirk and think it has achieved something. Not at all. In point of fact it has a couple more whites, both cane juice derived and distilled on their

Personally I have a thing for pot still hooch – they tend to have more oomph, more get-up-and-go, more pizzazz, better tastes. There’s more character in them, and they cheerfully exude a kind of muscular, addled taste-set that is usually entertaining and often off the scale. The Jamaicans and Guyanese have shown what can be done when you take that to the extreme. But on the other side of the world there’s this little number coming off a small column, and I have to say, I liked it even more than its pot still sibling, which may be the extra proof or the still itself, who knows.

Personally I have a thing for pot still hooch – they tend to have more oomph, more get-up-and-go, more pizzazz, better tastes. There’s more character in them, and they cheerfully exude a kind of muscular, addled taste-set that is usually entertaining and often off the scale. The Jamaicans and Guyanese have shown what can be done when you take that to the extreme. But on the other side of the world there’s this little number coming off a small column, and I have to say, I liked it even more than its pot still sibling, which may be the extra proof or the still itself, who knows.  Rumaniacs Review #124 | 0803

Rumaniacs Review #124 | 0803 Palate – Meh. Unadventurous. Watery alcohol. Pears, cucumbers in light brine, vanilla and sugar water depending how often one returns to the glass. Completely inoffensive and easy, which in this case means no effort required, since there’s almost nothing to taste and no effort is needed. Even the final touch of lemon zest doesn’t really save it.

Palate – Meh. Unadventurous. Watery alcohol. Pears, cucumbers in light brine, vanilla and sugar water depending how often one returns to the glass. Completely inoffensive and easy, which in this case means no effort required, since there’s almost nothing to taste and no effort is needed. Even the final touch of lemon zest doesn’t really save it.

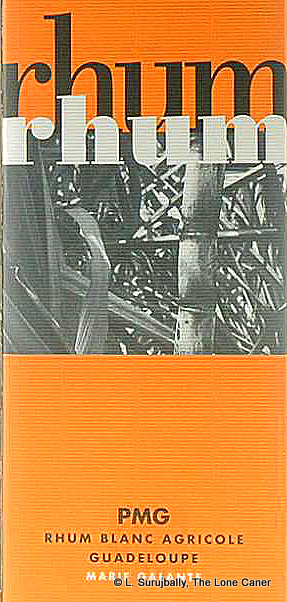

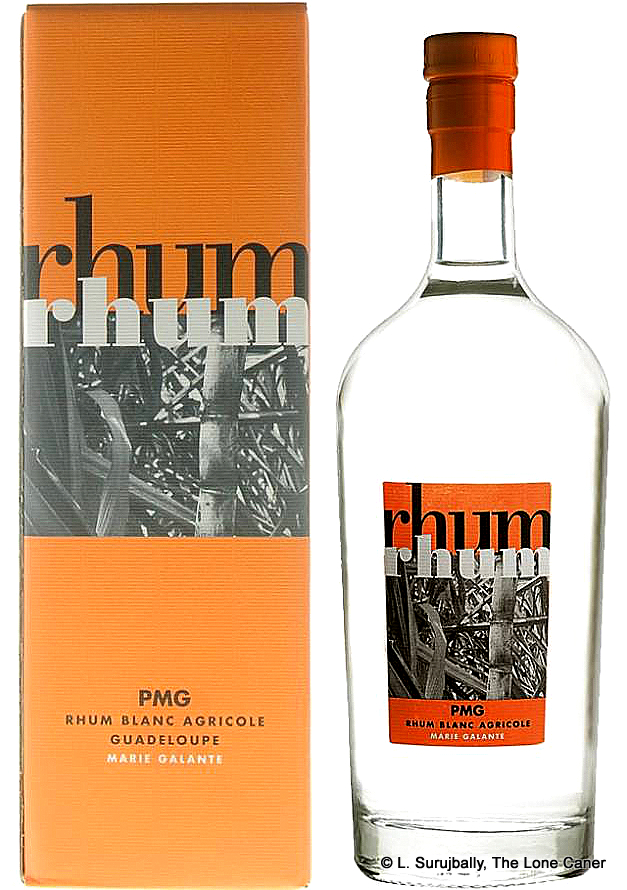

Although the plan was always to sell white (unaged) rhum, some was also laid away to age and the aged portion turned into the “Liberation” series in later years. The white was a constant, however, and remains on sale to this day – this orange-labelled edition was 56% ABV and I believe it is always released together with a green-labelled version at 41% ABV for gentler souls. It doesn’t seem to have been marked off by year in any way, and as far as I am aware production methodology remains consistent year in and year out.

Although the plan was always to sell white (unaged) rhum, some was also laid away to age and the aged portion turned into the “Liberation” series in later years. The white was a constant, however, and remains on sale to this day – this orange-labelled edition was 56% ABV and I believe it is always released together with a green-labelled version at 41% ABV for gentler souls. It doesn’t seem to have been marked off by year in any way, and as far as I am aware production methodology remains consistent year in and year out. From the description I’m giving, it’s clear that I like this rhum, a lot. I think it mixes up the raw animal ferocity of a more primitive cane juice rhum with the crisp and clear precision of a Martinique blanc, while just barely holding the damn thing on a leash, and yeah, I enjoyed it immensely. I do however, wonder about its accessibility and acceptance given the price, which is around $90 in the US. It varies around the world and on Rum Auctioneer it averaged out around £70 (crazy, since

From the description I’m giving, it’s clear that I like this rhum, a lot. I think it mixes up the raw animal ferocity of a more primitive cane juice rhum with the crisp and clear precision of a Martinique blanc, while just barely holding the damn thing on a leash, and yeah, I enjoyed it immensely. I do however, wonder about its accessibility and acceptance given the price, which is around $90 in the US. It varies around the world and on Rum Auctioneer it averaged out around £70 (crazy, since  Hampden gets so many kudos these days from its relationship with

Hampden gets so many kudos these days from its relationship with  The rum displays all the attributes that made the estate’s name after 2016 when they started supplying their rums to others and began bottling their own. It’s a rum that’s astonishingly stuffed with tastes from all over the map, not always in harmony but in a sort of cheerful screaming chaos that shouldn’t work…except that it does. More sensory impressions are expended here than in any rum of recent memory (and I remember

The rum displays all the attributes that made the estate’s name after 2016 when they started supplying their rums to others and began bottling their own. It’s a rum that’s astonishingly stuffed with tastes from all over the map, not always in harmony but in a sort of cheerful screaming chaos that shouldn’t work…except that it does. More sensory impressions are expended here than in any rum of recent memory (and I remember  Rumaniacs Review #122 | 0785

Rumaniacs Review #122 | 0785

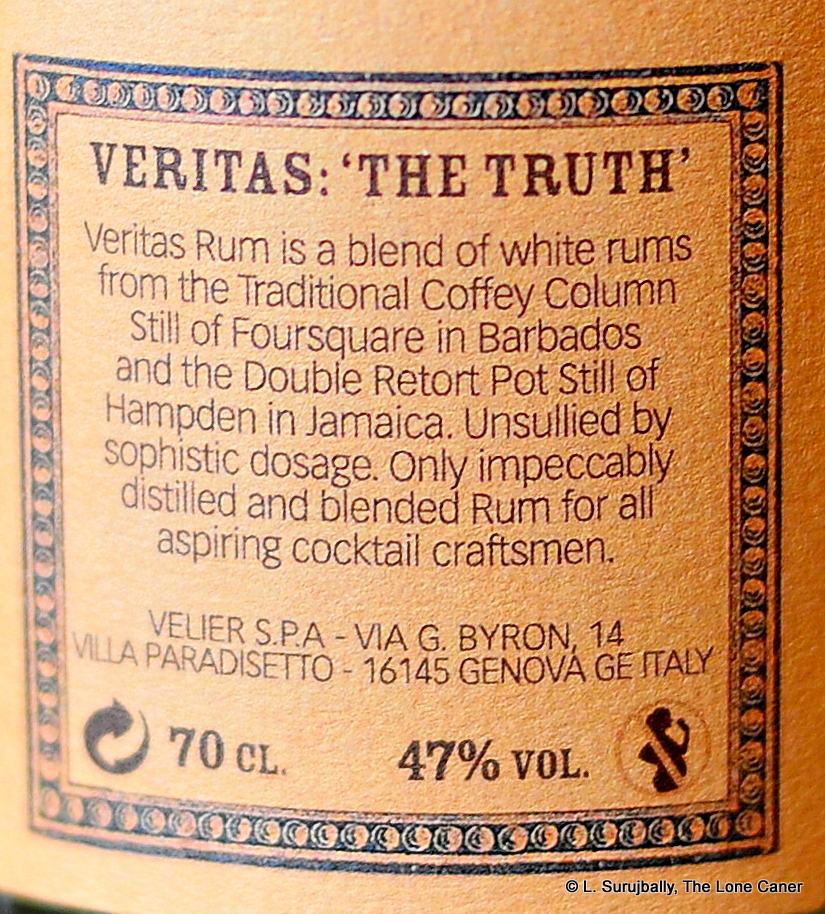

When it really comes down to it, the only thing I didn’t care for is the name. It’s not that I wanted to see “Jamados” or “Bamaica” on a label (one shudders at the mere idea) but I thought “Veritas” was just being a little too hamfisted with respect to taking a jab at Plantation in the ongoing feud with Maison Ferrand (the statement of “unsullied by sophistic dosage” pointed there). As it turned out, my opinion was not entirely justified, as Richard Seale noted in a comment to to me that… “It was intended to reflect the simple nature of the rum – free of (added) colour, sugar or anything else including at that time even addition from wood. The original idea was for it to be 100% unaged. In the end, when I swapped in aged pot for unaged, it was just markedly better and just ‘worked’ for me in the way the 100% unaged did not.” So for sure there was more than I thought at the back of this title.

When it really comes down to it, the only thing I didn’t care for is the name. It’s not that I wanted to see “Jamados” or “Bamaica” on a label (one shudders at the mere idea) but I thought “Veritas” was just being a little too hamfisted with respect to taking a jab at Plantation in the ongoing feud with Maison Ferrand (the statement of “unsullied by sophistic dosage” pointed there). As it turned out, my opinion was not entirely justified, as Richard Seale noted in a comment to to me that… “It was intended to reflect the simple nature of the rum – free of (added) colour, sugar or anything else including at that time even addition from wood. The original idea was for it to be 100% unaged. In the end, when I swapped in aged pot for unaged, it was just markedly better and just ‘worked’ for me in the way the 100% unaged did not.” So for sure there was more than I thought at the back of this title.

The results of all that micro-management are amazing.The nose, fierce and hot, lunges out of the bottle right away, hardly needs resting, and is immediately redolent of brine, olives, sugar water,and wax, combined with lemony botes (love those), the dustiness of cereal and the odd note of sweet green peas smothered in sour cream (go figure). Secondary aromas of fresh cane sap, grass and sweet sugar water mixed with light fruits (pears, guavas, watermelons) soothe the abused nose once it settles down.

The results of all that micro-management are amazing.The nose, fierce and hot, lunges out of the bottle right away, hardly needs resting, and is immediately redolent of brine, olives, sugar water,and wax, combined with lemony botes (love those), the dustiness of cereal and the odd note of sweet green peas smothered in sour cream (go figure). Secondary aromas of fresh cane sap, grass and sweet sugar water mixed with light fruits (pears, guavas, watermelons) soothe the abused nose once it settles down.

Normally, such a rum wouldn’t interest me much, but with the massive reputations the New Jamaicans have been building for themselves, it made me curious so I grudgingly parted with some coin to get a sample. That was the right decision, because this thing turned out to be less an undiscovered steal than a low-rent Jamaican wannabe for those who don’t care about and can’t tell one Jamaican rum from another, know Appleton and stop there. The rum takes great care not to go beyond such vanilla illusions, since originality is not its forte and it takes inoffensive pleasing-the-sipper as its highest goal.

Normally, such a rum wouldn’t interest me much, but with the massive reputations the New Jamaicans have been building for themselves, it made me curious so I grudgingly parted with some coin to get a sample. That was the right decision, because this thing turned out to be less an undiscovered steal than a low-rent Jamaican wannabe for those who don’t care about and can’t tell one Jamaican rum from another, know Appleton and stop there. The rum takes great care not to go beyond such vanilla illusions, since originality is not its forte and it takes inoffensive pleasing-the-sipper as its highest goal.

The word “Lontan” is difficult to pin down – in Haitian Creole, it means “long” and “long ago” while in old French it was “lointain” and meant “distant” and “far off”, and neither explains why Savanna picked it (though many establishments around the island use it in their names as well, so perhaps it’s an analogue to the english “Ye Olde…”). Anyway, aside from the traditional, creol, Intense and Metis ranges of rums (to which have now been added several others) there is this Lontan series – these are all variations of Grand Arôme rums, finished or not, aged or not, full-proof or not, which are distinguished by a longer fermentation period and a higher ester count than usual, making them enormously flavourful.

The word “Lontan” is difficult to pin down – in Haitian Creole, it means “long” and “long ago” while in old French it was “lointain” and meant “distant” and “far off”, and neither explains why Savanna picked it (though many establishments around the island use it in their names as well, so perhaps it’s an analogue to the english “Ye Olde…”). Anyway, aside from the traditional, creol, Intense and Metis ranges of rums (to which have now been added several others) there is this Lontan series – these are all variations of Grand Arôme rums, finished or not, aged or not, full-proof or not, which are distinguished by a longer fermentation period and a higher ester count than usual, making them enormously flavourful.

As for the taste when sipped, “uninspiring” might be the kindest word to apply. It’s so light as to be nonexistent, and just seemed so…

As for the taste when sipped, “uninspiring” might be the kindest word to apply. It’s so light as to be nonexistent, and just seemed so…

Opinion / Company background

Opinion / Company background

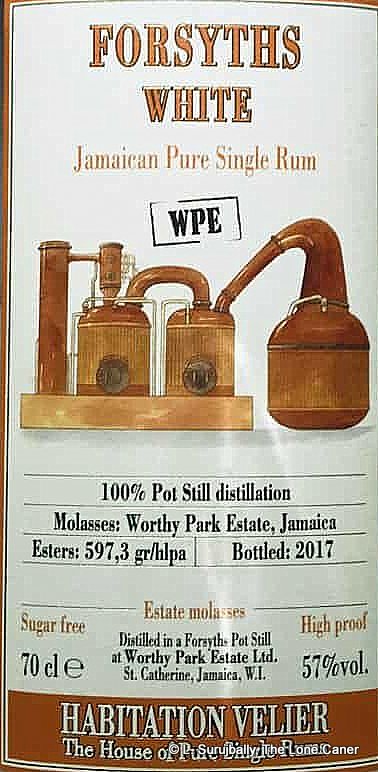

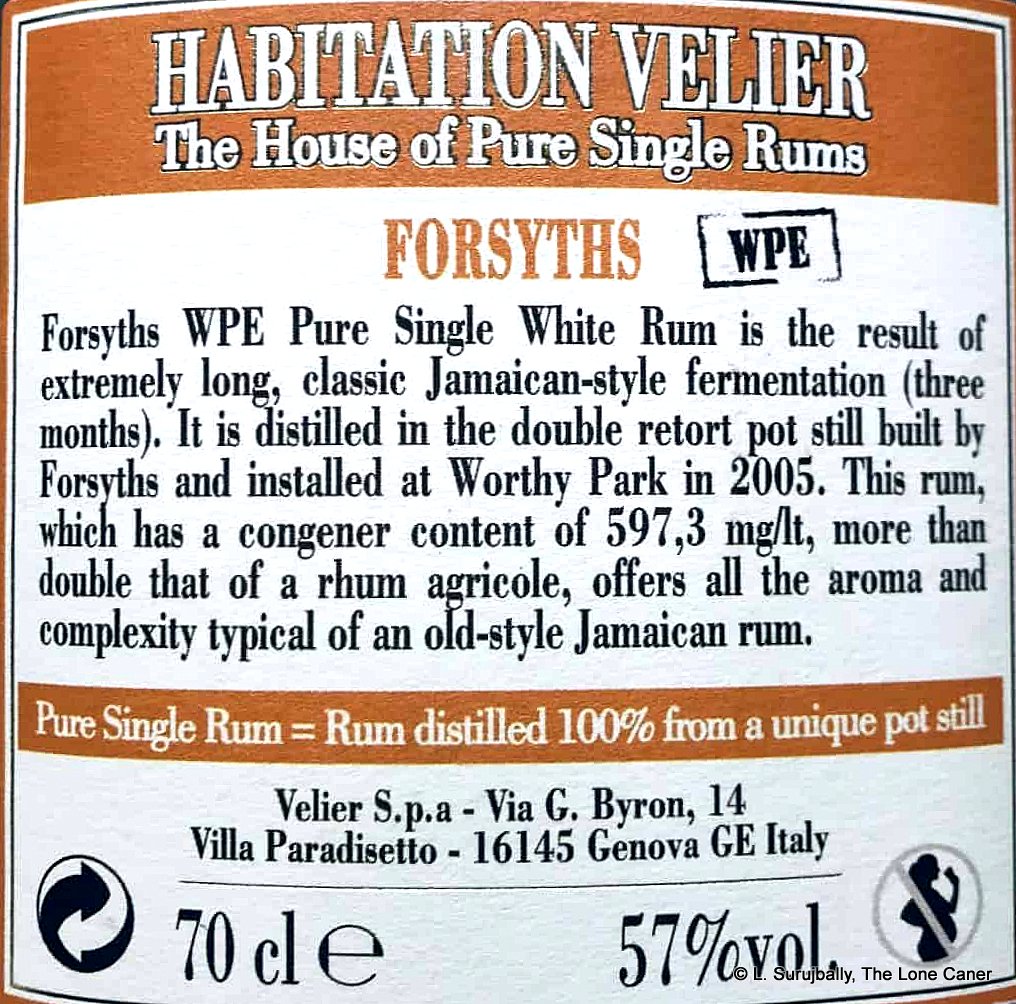

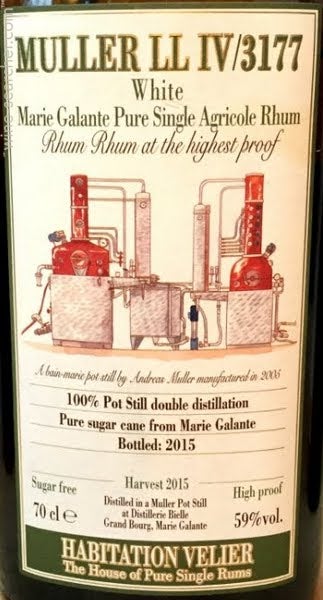

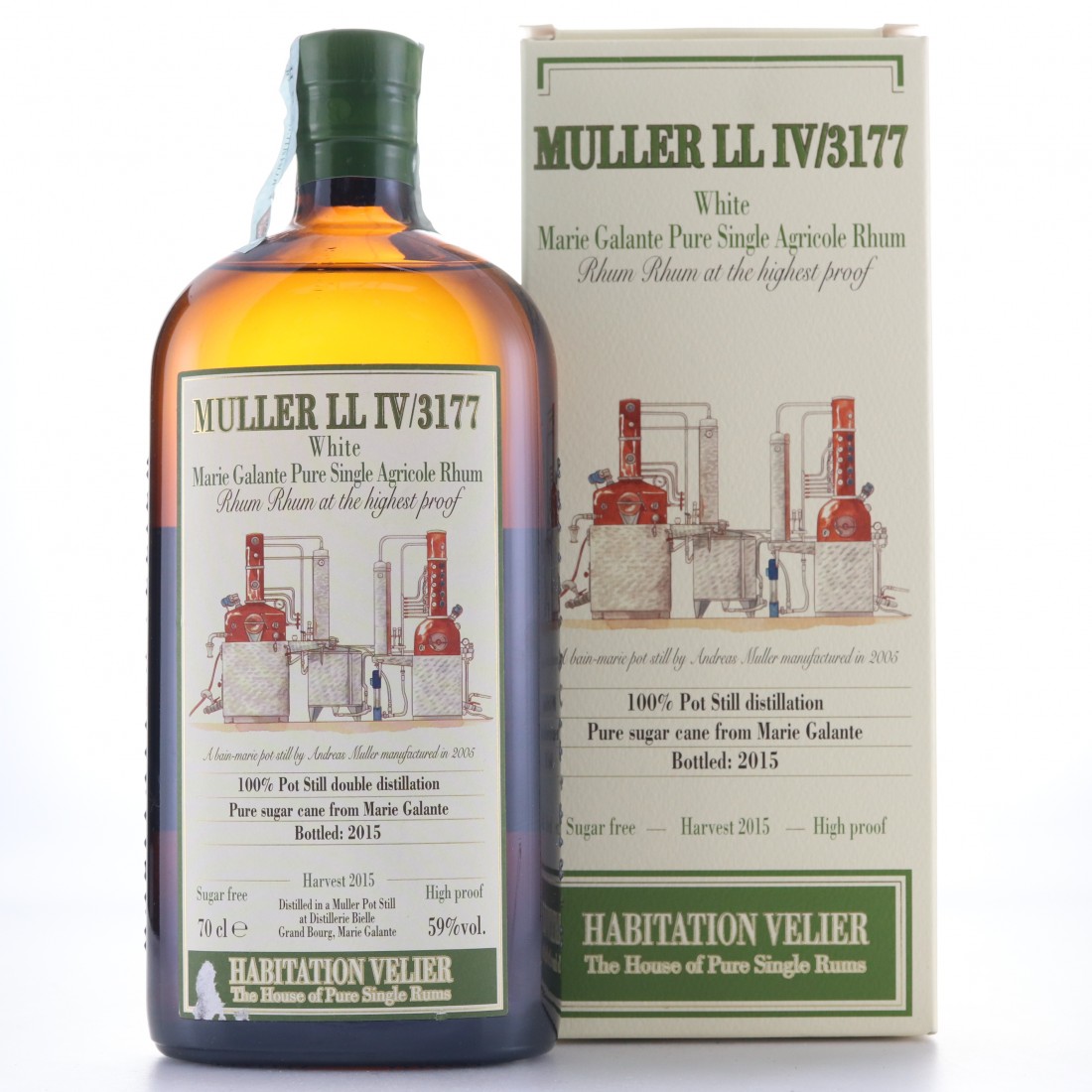

So let’s spare some time to look at this rather unique white rum released by Habitation Velier, one whose brown bottle is bolted to a near-dyslexia-inducing name only a rum geek or still-maker could possibly love. And let me tell you, unaged or not, it really is a monster truck of tastes and flavours and issued at precisely the right strength for what it attempts to do.

So let’s spare some time to look at this rather unique white rum released by Habitation Velier, one whose brown bottle is bolted to a near-dyslexia-inducing name only a rum geek or still-maker could possibly love. And let me tell you, unaged or not, it really is a monster truck of tastes and flavours and issued at precisely the right strength for what it attempts to do. Evaluating a rum like this requires some thinking, because there are both familiar and odd elements to the entire experience. It reminds me of

Evaluating a rum like this requires some thinking, because there are both familiar and odd elements to the entire experience. It reminds me of

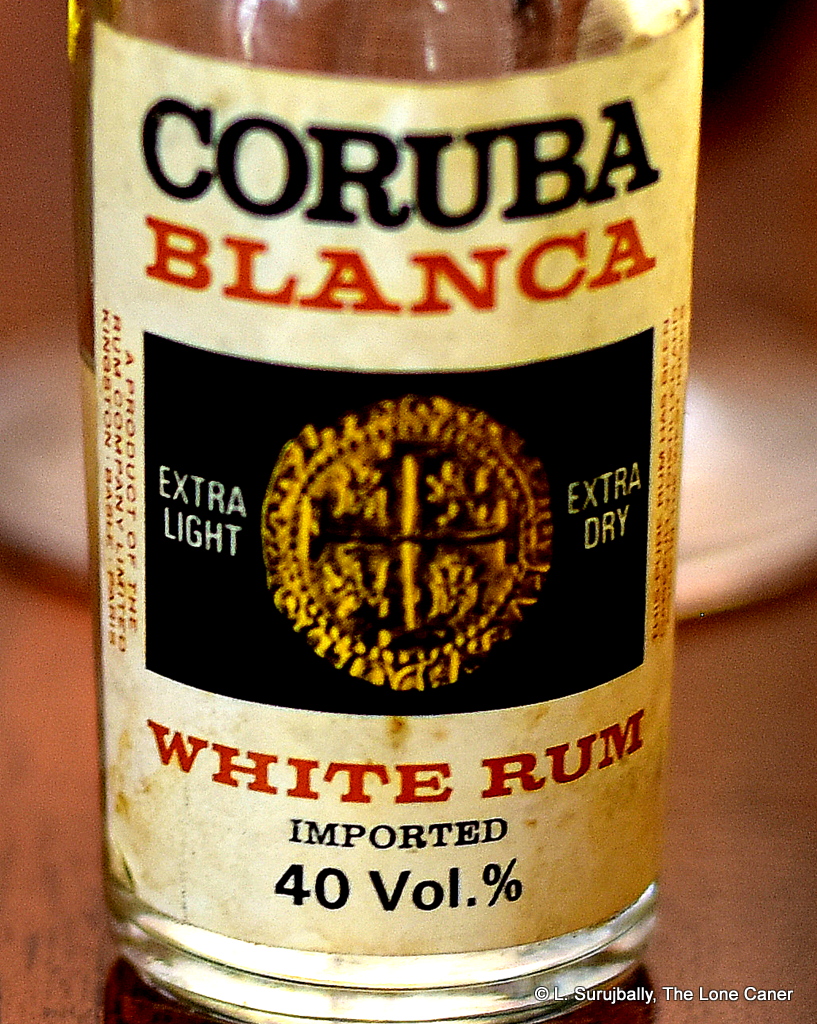

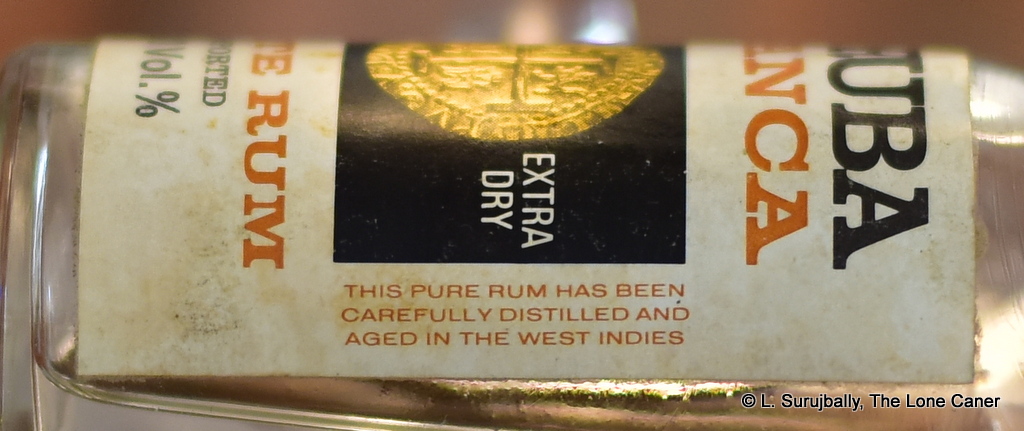

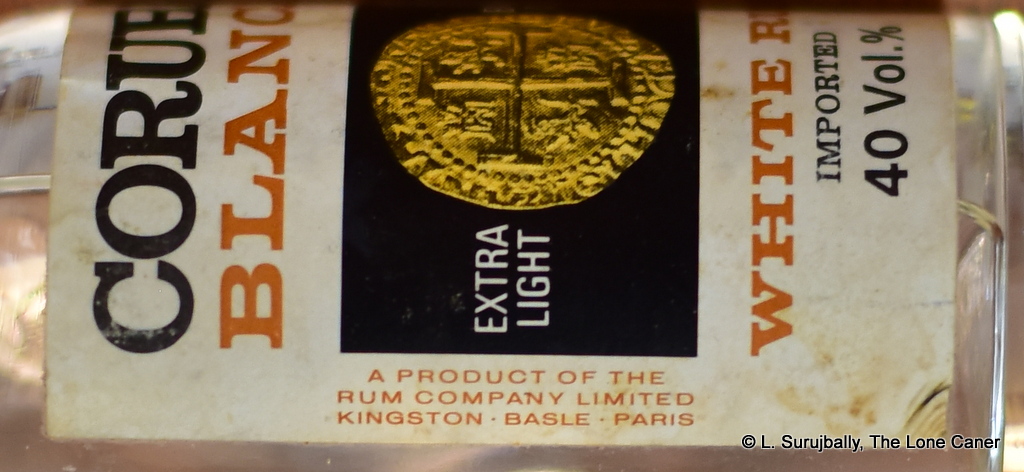

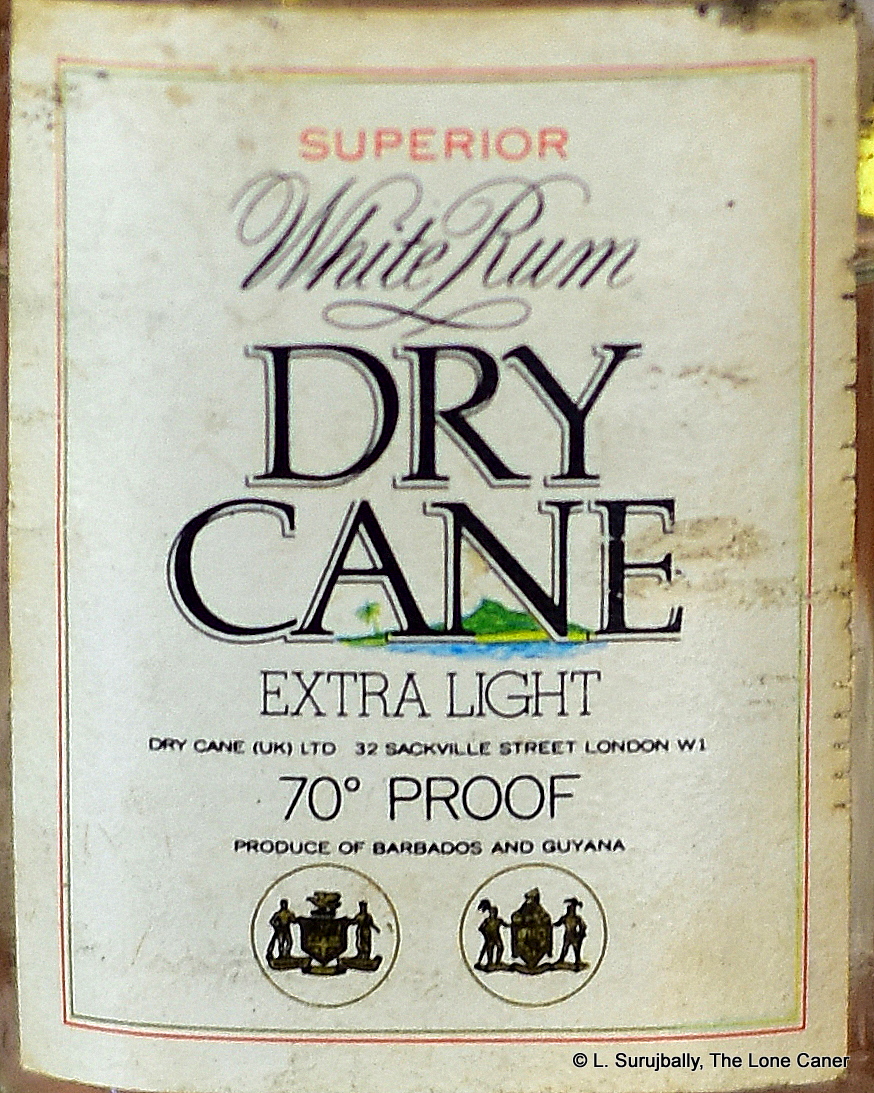

My inference is therefore that Dry Cane was a financing vehicle or shell company or wholly owned subsidiary set up for a short time to limit the exposure of the parent company (or Kinloch), as it dabbled in being an independent bottler — and just as quickly retreated, for no further products were ever made so far as I can tell. But since S&S also acquired a Gibraltar drinks franchise in 1968 and gained the concession to operate a duty free shop at Gibraltar airport in 1973, I suspect this was the rationale behind creating the rums in the first place, through the reason for its cessation is unknown. Certainly by the time S&S moved out of Sackville Street in the 1980s and to Gibraltar (where they remain to this day as part of a large conglomerate), the rum was no longer on sale.

My inference is therefore that Dry Cane was a financing vehicle or shell company or wholly owned subsidiary set up for a short time to limit the exposure of the parent company (or Kinloch), as it dabbled in being an independent bottler — and just as quickly retreated, for no further products were ever made so far as I can tell. But since S&S also acquired a Gibraltar drinks franchise in 1968 and gained the concession to operate a duty free shop at Gibraltar airport in 1973, I suspect this was the rationale behind creating the rums in the first place, through the reason for its cessation is unknown. Certainly by the time S&S moved out of Sackville Street in the 1980s and to Gibraltar (where they remain to this day as part of a large conglomerate), the rum was no longer on sale. Palate – Light and inoffensive, completely bland. Pears, sugar water, some mint. You can taste a smidgen of alcohol behind all that, it’s just that there’s nothing really serious backing it up or going on.

Palate – Light and inoffensive, completely bland. Pears, sugar water, some mint. You can taste a smidgen of alcohol behind all that, it’s just that there’s nothing really serious backing it up or going on.

The rum was standard strength (40%), so it came as little surprise that the palate was very light, verging on airy – one burp and it was gone forever. Faintly sweet, smooth, warm, vaguely fruity, and again those minerally metallic notes could be sensed, reminding me of an empty tin can that once held peaches in syrup and had been left to dry. Further notes of vanilla, a single cherry and that was that, closing up shop with a finish that breathed once and died on the floor. No, really, that was it.

The rum was standard strength (40%), so it came as little surprise that the palate was very light, verging on airy – one burp and it was gone forever. Faintly sweet, smooth, warm, vaguely fruity, and again those minerally metallic notes could be sensed, reminding me of an empty tin can that once held peaches in syrup and had been left to dry. Further notes of vanilla, a single cherry and that was that, closing up shop with a finish that breathed once and died on the floor. No, really, that was it.

Whatever the case, the rum was as fierce as the Diamond, and even at a microscopically lower proof, it took no prisoners. It exploded right out of the glass with sharp, hot, violent aromas of tequila, rubber, salt, herbs and really good olive oil. If you blinked you could see it boiling. It swayed between sweet and salt, between soya, sugar water, squash, watermelon, papaya and the tartness of hard yellow mangoes, and to be honest, it felt like I was sniffing a bottle shaped mass of whup-ass (the sort of thing Guyanese call “regular”).

Whatever the case, the rum was as fierce as the Diamond, and even at a microscopically lower proof, it took no prisoners. It exploded right out of the glass with sharp, hot, violent aromas of tequila, rubber, salt, herbs and really good olive oil. If you blinked you could see it boiling. It swayed between sweet and salt, between soya, sugar water, squash, watermelon, papaya and the tartness of hard yellow mangoes, and to be honest, it felt like I was sniffing a bottle shaped mass of whup-ass (the sort of thing Guyanese call “regular”).