In the current lineup from Goslings, the Bermuda-based blenders and bottlers (as far as I know they are not distilling rums), there are four different quasi-premium products: the “Spirited Seas” 44% ABV rum which is partially matured on the high seas, the “Papa Seal” single barrel aged rum at 41.5%, and two variations of the “Family Reserve Old Rum” at 40%, one of which we will look at today.

In the current lineup from Goslings, the Bermuda-based blenders and bottlers (as far as I know they are not distilling rums), there are four different quasi-premium products: the “Spirited Seas” 44% ABV rum which is partially matured on the high seas, the “Papa Seal” single barrel aged rum at 41.5%, and two variations of the “Family Reserve Old Rum” at 40%, one of which we will look at today.

In the last century or before it may really have been the practise for estates and distilleries – many owned privately – to hold back some exceptional barrels to bottle for the lords of the manor and their families, or members of the upper management. Such “reserved” stocks, often older than the norm, were gradually commercialized, and released with titles like Chairman’s Reserve, Family Reserve, Private Stock, President’s Choice, or whatever, meant to capitalize on their unique, limited, elevated nature. They are, of course, meant to be premium rums, and priced accordingly, and if we proles could afford a bottle, then we could sip – vicariously, to be sure – at the tables of the upper crust and consider ourselves grateful (or so the theory goes).

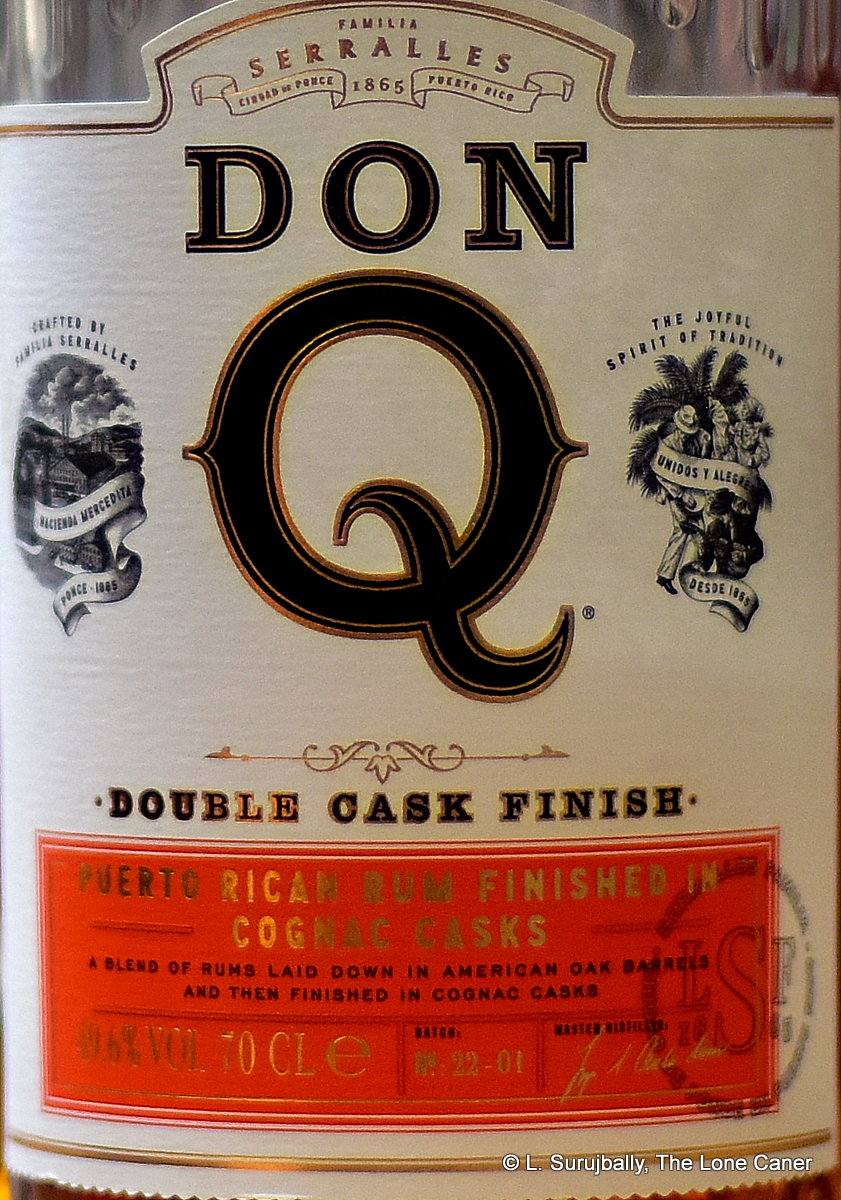

The Gosling’s Family Reserve Old Rum, first brought to market in the very early 2000s (I’ve heard 2003, or 2005), is one of these. Subject to my opinion below, let’s accept (for now) that it’s a molasses-based pot-column blend, aged for sixteen to nineteen years, released at 40% and costing around Can$70-100, when it can be found.

Considering the nose showcases some of its weaknesses to a modern audiences: it’s thin, it’s weak and takes far too long to open up. After about ten minutes in a covered glass, there’s little to mark it as being premium anything: we get some wet grass, dark cherries, cinnamon, caramel, toffee, a touch of white chocolate, and some dried raisins. With effort, one might make out some overripe oranges, bananas and walnuts, but that’s reaching.

Considering the nose showcases some of its weaknesses to a modern audiences: it’s thin, it’s weak and takes far too long to open up. After about ten minutes in a covered glass, there’s little to mark it as being premium anything: we get some wet grass, dark cherries, cinnamon, caramel, toffee, a touch of white chocolate, and some dried raisins. With effort, one might make out some overripe oranges, bananas and walnuts, but that’s reaching.

The palate is similarly unprepossessing. It is soft and easy to sip, of course – the strength and the ageing have sanded off any rough edges – with notes of leather, vanilla, sweet smoky paprika and freshly cut bell peppers, plus honey and maybe a wine-y hint or two. Some raisins, some crushed nuts, stale coffee grounds and all this leads to a short, lacklustre finish that’s an indeterminate mish-mash of caramel, vanilla, orange peel, and those coffee grounds again.

From these brief notes, you can clearly see I’m not impressed, because, for a rum positioning itself as special, there’s not enough to justify either the cachet or the price. For its time, I guess it did its job. In this day and age, it’s fails the Stewart Affordability Conjecture, in spades. It’s clearly a rum, decent enough – it just doesn’t deliver anything we don’t already get elsewhere with more flair at lesser prices. And if you want a comparison, just take down any Foursquare ECS edition bottled at a similar strength, and meditate on the difference between this pleasant but one-dimensional rum, and real craftsmanship. But you know, the virtual disappearance of the rum from any kind of “best-of” lists or medal winners in recent years makes the karmic point better than any rebuttal I could write here, so I’ll just shrug, smile and move on.

(#1130)(80/100) ⭐⭐⭐

Company background (from Review #1129)

Gosling’s hails from Bermuda, which is a British Overseas Territory, Britain’s oldest: the company is closely identified with the island and is, aside from tourism and some manufacturing, a mainstay of Bermuda’s non-financial-services economy.

The Gosling enterprise has been in business on Bermuda since 1806, when the ship’s charter for business in the USA expired while on the high seas (the ship was apparently becalmed for longer than expected). So instead of landing in Virginia, James Gosling, the son of a wine and spirits merchant in England, went ashore in St. George’s instead, and set up shop there with his brother Ambrose, trading in spirits he had brought with him. Rum blending from imported distillates began in 1860, with the Old Rum brand launching three years later. The company’s rums were originally sold directly from barrels to customers who brought their own bottles, a practise that continued until the Great War; however, Goslings’ rums’ popularity and sales took off when they began salvaging used champagne bottles from the British navy’s officer’s mess, filling those with rum and sealing them with black wax.

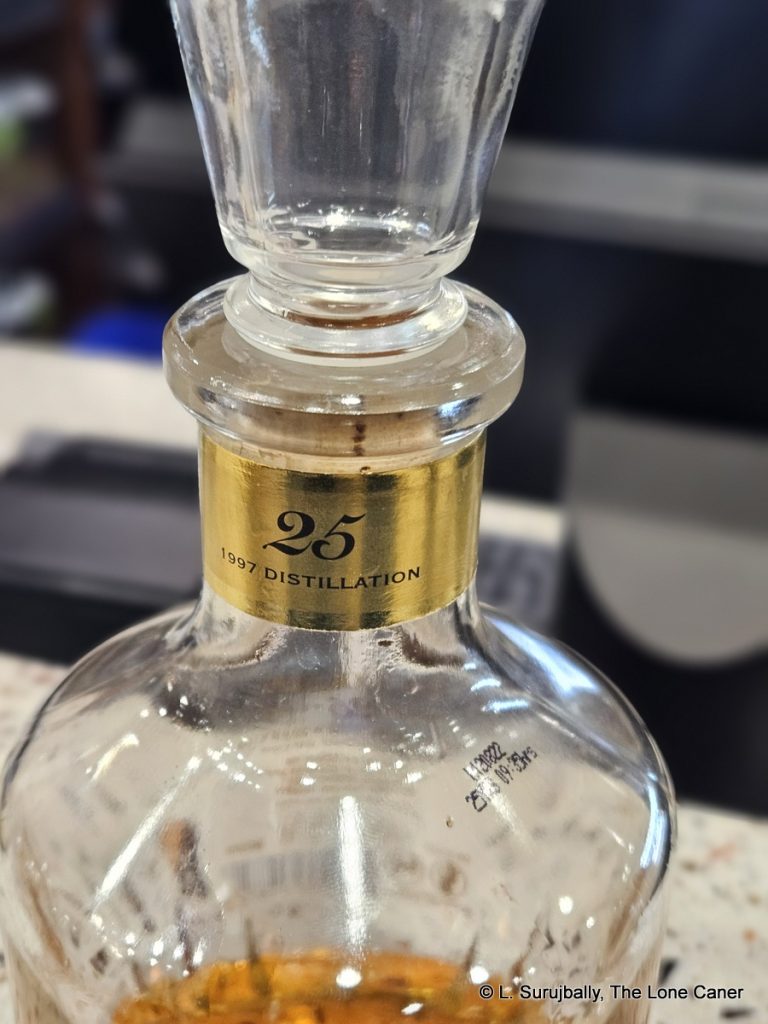

The Old Rum was renamed the Black Seal, with the now-famous seal logo designed and coming into use in 1948: the champagne bottles are rarer now, used only for the Family Reserve line, but the logo has remained in use ever since. It is the company’s flagship brand and goes hand in glove with their signature cocktail “The Dark ‘n’ Stormy, which was developed in the mid 1960s and trademarked in 1980 (and rigorously enforced).

Commentary | Opinion

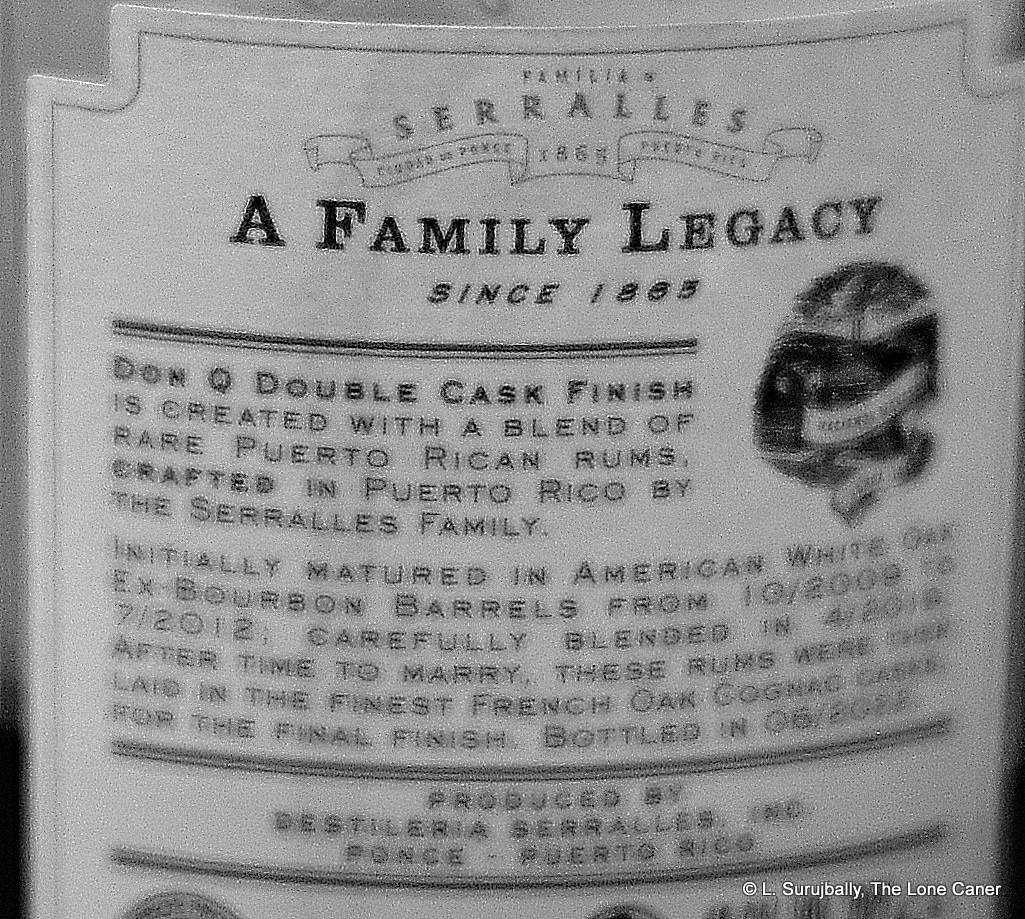

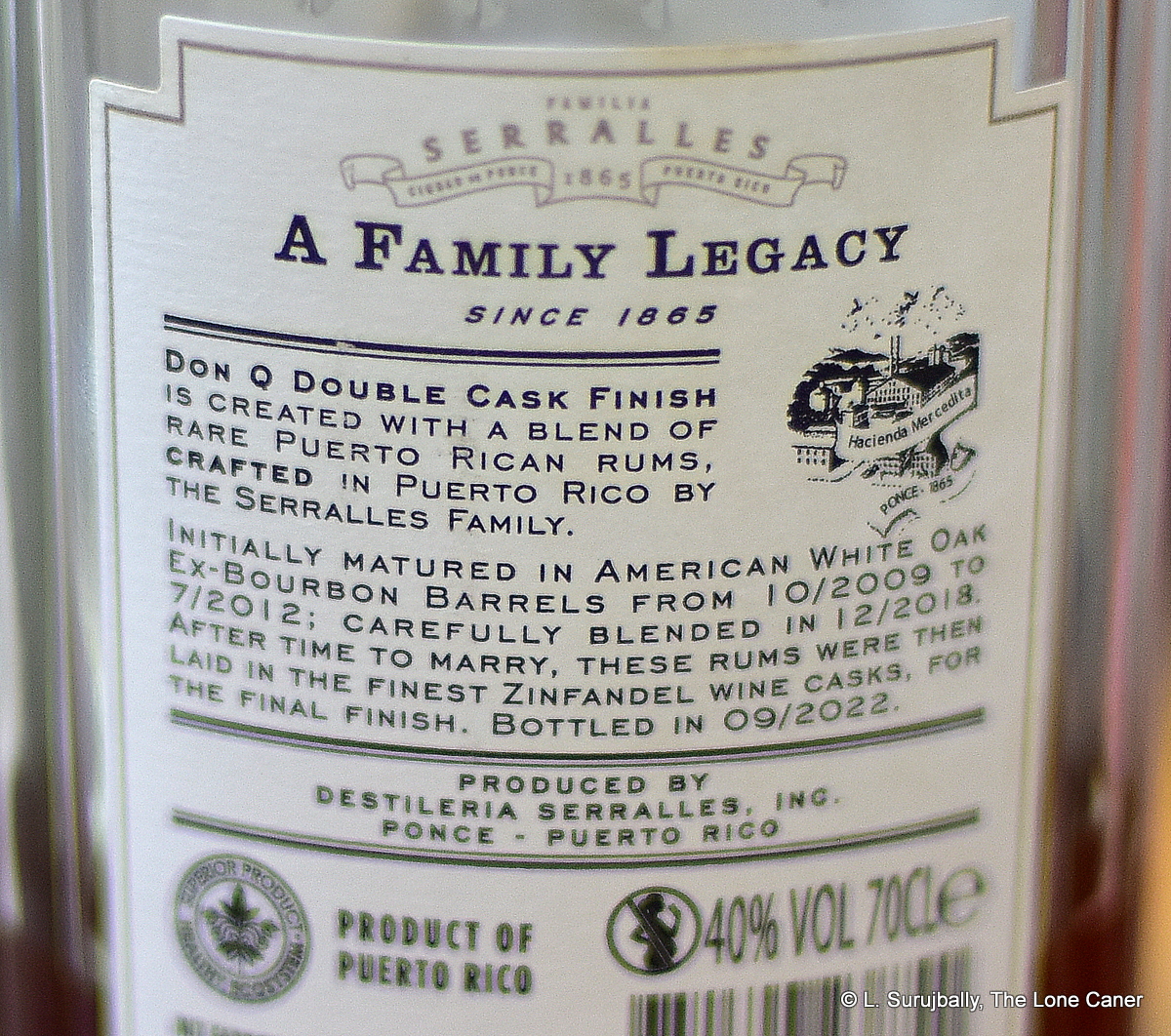

First released in 2005, the Family Reserve Old Rum proudly adheres — on both the label and the website — to all the annoying lack of disclosure I remarked on with the 151 Overproof. The provenance is murky, the outturn is unknown, the blend is supposedly but unconfirmed to be pot and column distillates, and it’s aged “up to” sixteen years – hardly the best way to flog a much-touted premium product which the Caribbean Journal named its Rum of the Year in 2012 (Goslings on their undated website entry for the rum, casually restates this as “the Caribbean Journal named Goslings Family Reserve Old Rum the No.1 aged rum in the world.”)

Maybe those were simpler and more innocent times in the rumiverse, and maybe my impatience with marketing-speak informs my snark. Frankly, it surpasses my understanding how in this modern day and age, when the provision of information has been a hotly discussed point for over a decade, we still have to be Sherlock Holmes to get some bare bones, basic info. Goslings positions the rum as some kind of premium rum while telling us almost nothing about it. It was perhaps understandable back in the day, but now, it’s indefensible.

Other notes

- Video recap link

- The bottle number is 4992/19 – my conjecture is that the last two digits represent the year of release.

Company Bio

Company Bio