Poisson-Père Labat, who worked for the most part with blancs, blends and mid range rhums, came late to the party of millesime expressions – at least, so far as I have been able to establish – and you’d be hard pressed to find any identifiable years’ rhums before 1985. Even now I don’t see the distillery releasing them very often, though of late they seem to be upping their game and have two or three top end single casks on sale right now.

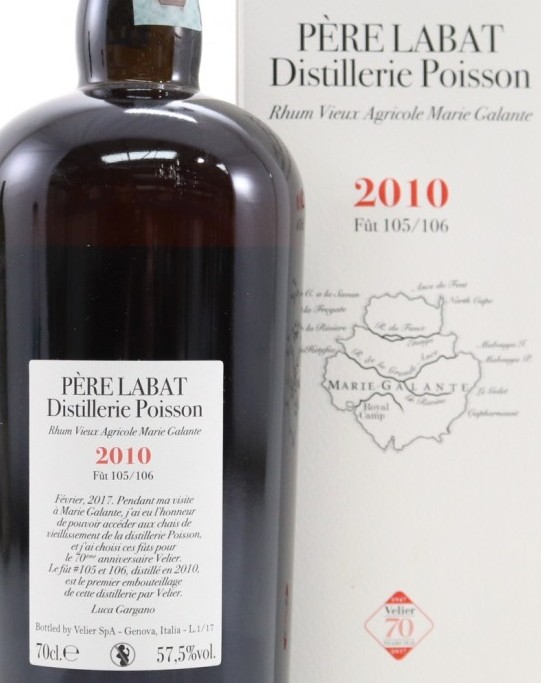

But that has not stopped others from working with the concept, and in 2017 Velier got their mitts on a pair of their barrels. That was the year in which, riding high on the success of the classic Demerara rums, the Trinidadian Caronis and the Habitation Velier series of pot still rums (among others), they celebrated the company’s 70th birthday. Though it should be made clear that this was the company’s birthday, not the 70th year of Luca Gargano’s association with that once-unknown little distributor, since he only bought it in the early 1970s.

In his book Nomade Tra I Barili Luca – with surprising brevity – describes his search for special barrels from around the world which exemplified his long association with the spirit, sought out and purchased for the “Anniversary Collection”; but concentrates his attention on the “Warren Khong” subset, those rums whose label designs were done by the Singapore painter. There were, however, other rhums in the series, like the Antigua Distillers’ 2012, or the two Neissons, or the Karukera 2008. And this one.

In his book Nomade Tra I Barili Luca – with surprising brevity – describes his search for special barrels from around the world which exemplified his long association with the spirit, sought out and purchased for the “Anniversary Collection”; but concentrates his attention on the “Warren Khong” subset, those rums whose label designs were done by the Singapore painter. There were, however, other rhums in the series, like the Antigua Distillers’ 2012, or the two Neissons, or the Karukera 2008. And this one.

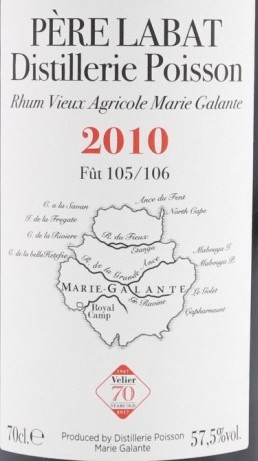

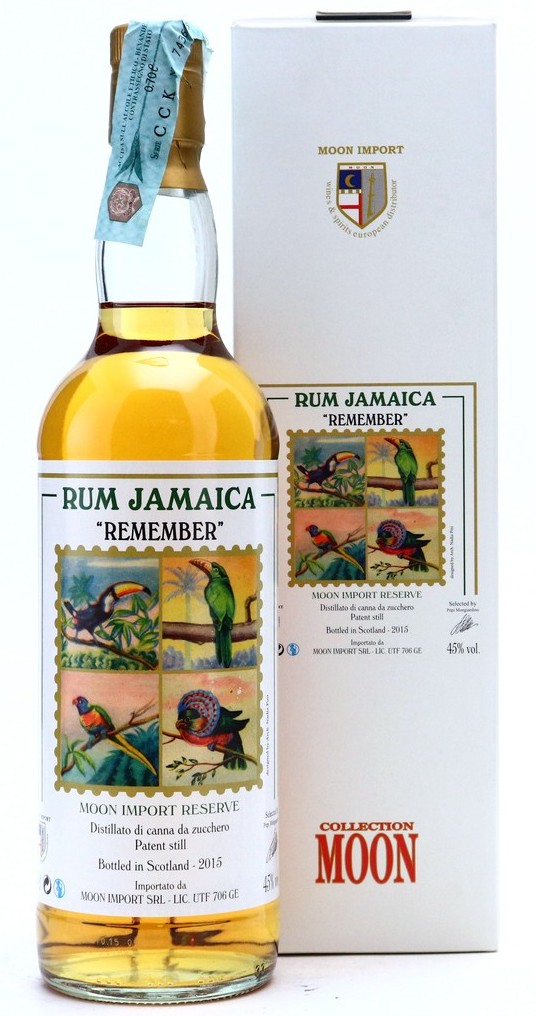

The rhum he selected from Poisson-Pere Labat has all the Velier hallmarks: neat minimalist label with an old map of Marie Galante, slapped onto that distinctive black bottle, with the unique font they have used since the Demeraras. Cane juice derived, 57.5% ABV, coming off a column still in 2010 and aged seven years in oak.

It’s a peculiar rhum on its own, this one, nothing like all the others that the distillery makes for its own brands. And that’s because it actually tastes more like a molasses-based rum of some age, than a true agricole. The initial nose says it all: cream, chocolate, coffee grounds and molasses, mixed with a whiff of damp brown sugar. It is only after this dissipates that we get citrus, fruits, grapes, raisins, prunes, and some of that herbal and grassy whiff which characterizes the true cane juice product. That said I must confess that I really like the balance among all these seemingly discordant elements.

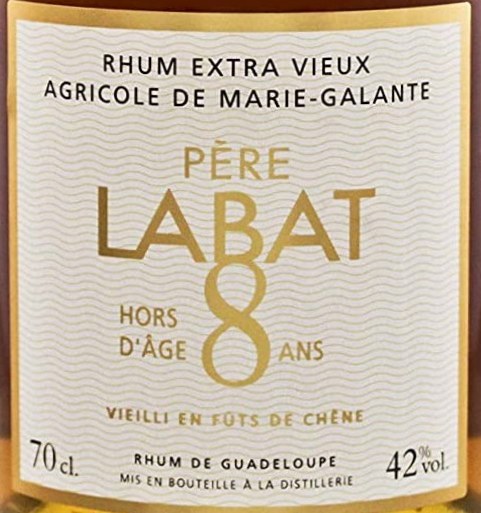

The comedown is with how it tastes, because compared to the bright and vivacious effervescence of the Pere Labat 3 and 8 year old and the younger blends, the Velier 7 YO comes off as rather average. It’s warm and firm, leading in with citrus zest, a trace of molasses, aromatic tobacco, licorice and dark fruits (when was the last time you read that in a cane juice rhum review?), together with the light creaminess of vanilla ice cream. There’s actually less herbal, “green” notes than on the nose, and even the finish has a brief and rather careless “good ‘nuff” vibe to it – medium long, with hints of green tea, lemon zest, some tartness of a lemon meringue pie sprinkled with brown sugar and then poof, it’s over.

Ultimately, I find it disappointing. Partly that’s because it’s impossible not to walk into any Velier experience without some level of expectations — which is why I’m glad I hid this sample among five others and tried the lot blind; I mean, I mixed up and went through the entire set twice — and Labat’s own rums, cheaper or younger, subtly equated or beat it, and one is just left asking with some bemused bafflement how on earth did that happen?

Ultimately, I find it disappointing. Partly that’s because it’s impossible not to walk into any Velier experience without some level of expectations — which is why I’m glad I hid this sample among five others and tried the lot blind; I mean, I mixed up and went through the entire set twice — and Labat’s own rums, cheaper or younger, subtly equated or beat it, and one is just left asking with some bemused bafflement how on earth did that happen?

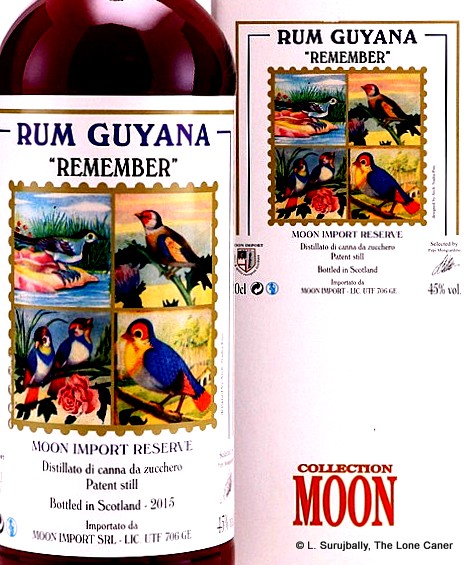

But it’s more than just preconceived notions and thwarted expectations, and also the way it presents, samples, tastes. I think they key might be that while the rhum does display an intriguing mix of muskiness and clarity, both at once, it’s not particularly complex or memorable – – and that’s a surprise for a rhum that starts so well, so intriguingly. And consider this also: can you recall it with excitement or fondness? Does it make any of your best ten lists? The rhum does not stand tall in either people’s memories, or in comparison to the regular set of rums Père Labat themselves put out the door. Everyone remembers the Antigua Distillers “Catch of the Day”, or one of the two Neissons, that St. Lucia or Mount Gilboa…but this one? Runt of the litter, I’m afraid. I’ll pass.

(#838)(83/100)

Other Notes

- For those who want more detailed background information, the company biography of Velier and a brief history of Pere Labat are both in the “Makers” section of this website.

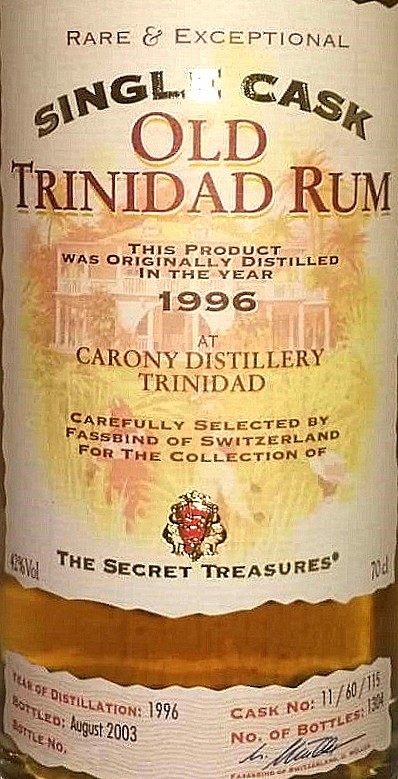

There are some older bottles in the review queue for products from what I term the “classic” era of the Swiss / German outfit of Secret Treasures, and it’s perhaps time to push them out the door in case some curious person ever wants to research them for an auction listing or something. Because what Secret Treasures are making now is completely different from what they did then, as I remarked in my brief company notes for

There are some older bottles in the review queue for products from what I term the “classic” era of the Swiss / German outfit of Secret Treasures, and it’s perhaps time to push them out the door in case some curious person ever wants to research them for an auction listing or something. Because what Secret Treasures are making now is completely different from what they did then, as I remarked in my brief company notes for  In the maelstrom of ongoing indie releases coming at us from every direction almost every month, it’s easy to overlook some of the older rums, or even some of the older companies. Secret Treasures is one of these — I had discovered their charms on the same trip where I found the first Veliers, all those long years ago, at a time when the concept of independent bottlers was a relatively small scale phenomenon. Back then I bought the company’s

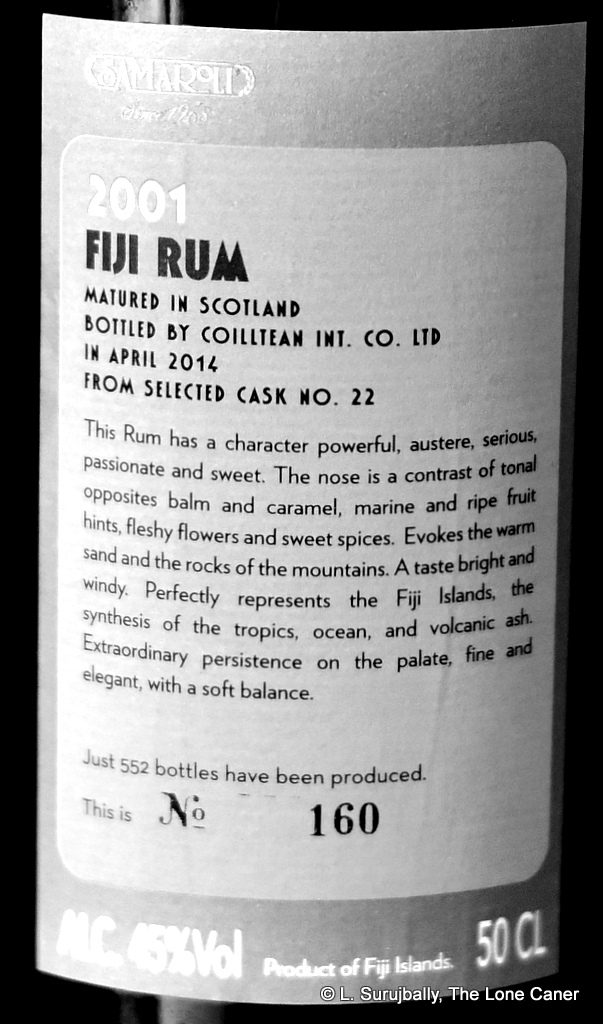

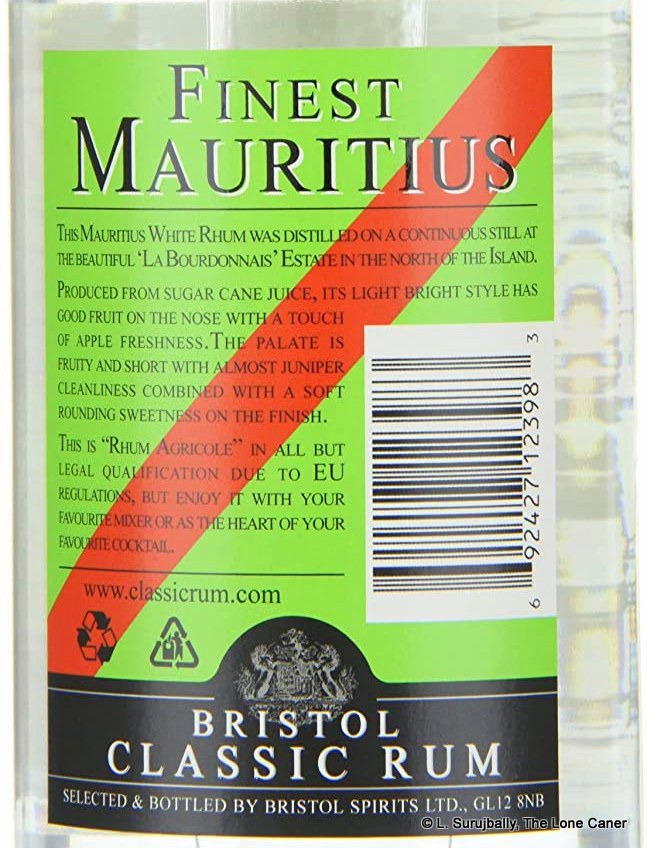

In the maelstrom of ongoing indie releases coming at us from every direction almost every month, it’s easy to overlook some of the older rums, or even some of the older companies. Secret Treasures is one of these — I had discovered their charms on the same trip where I found the first Veliers, all those long years ago, at a time when the concept of independent bottlers was a relatively small scale phenomenon. Back then I bought the company’s  A salty sweet sugar water greets the tongue with warmth and firmness. All the fleshy and watery fruits we’re familiar with parade around – pears, watermelons, white guavas, papaya, kiwi fruits, even cucumbers all take a bow. A trace of olives and occasional whiff of strawberries and petrol are barely noticeable, so one can only wonder where, after such a promising beginning, they all vanished to. Eloped, maybe. Certainly they bailed and left the rum with nothing but memories and a good wish to lead to its inevitably disappointing denouement, which was short, breathy, light and watery, and barely registered some vanilla, brine, a fruit or two and exactly zero points of distinction.

A salty sweet sugar water greets the tongue with warmth and firmness. All the fleshy and watery fruits we’re familiar with parade around – pears, watermelons, white guavas, papaya, kiwi fruits, even cucumbers all take a bow. A trace of olives and occasional whiff of strawberries and petrol are barely noticeable, so one can only wonder where, after such a promising beginning, they all vanished to. Eloped, maybe. Certainly they bailed and left the rum with nothing but memories and a good wish to lead to its inevitably disappointing denouement, which was short, breathy, light and watery, and barely registered some vanilla, brine, a fruit or two and exactly zero points of distinction.