Much of the perception of small and new companies’ rums is tied up in their founders and how they interact with the general public. Perhaps nowhere is this both easier and harder to do than in the United States – easier because of the “plucky little engine that could” mythos of the solo tinkerer, harder because of the sheer geographical scale of the country. Too, it’s one thing to make a new rum, quite another to get a Je m’en fous public of Rhett Butlers to give a damn. And this is why the chatterati and online punditocracy barely know any of the hundreds of small distilleries making rum in the USA (listed with such patience by the Burrs and Will Hoekenga in their websites)…but are often very much aware of the colourful founders of such enterprises.

That said, even within this ocean of relative indifference, a few companies and names stand out. We’ve been hearing more about Montanya Distillery and master blender Karen Hoskin, everyone knows about Bailey Prior and the Real McCoy line, Lost Spirits may have faded from view but has great name recognition, Koloa has been making rum for ages, Pritchard’s and Richland are almost Old Stalwarts these days, the Eastern seaboard has its fair share of up and coming little rinky-dinks…and then there’s Privateer and its driven, enthusiastic, always-engaged master blender, Maggie Campbell, whose sense of humour can be gauged by her Instagram handle, “Half Pint Maggie.”

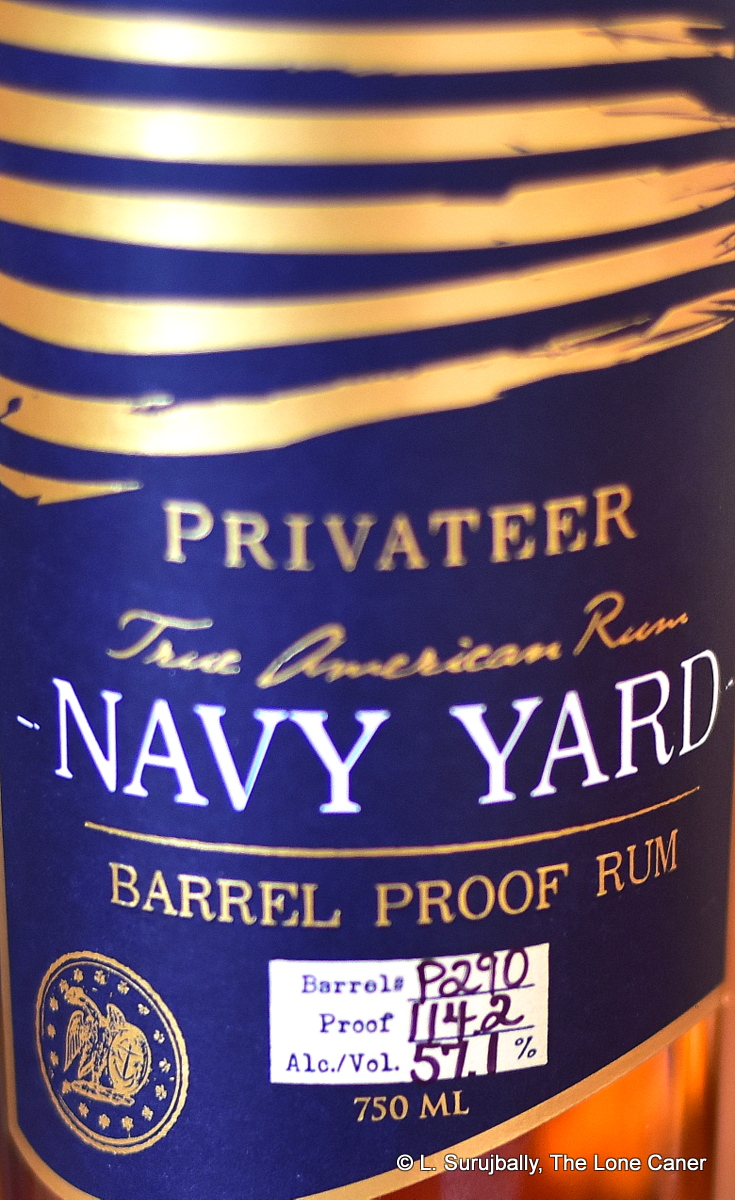

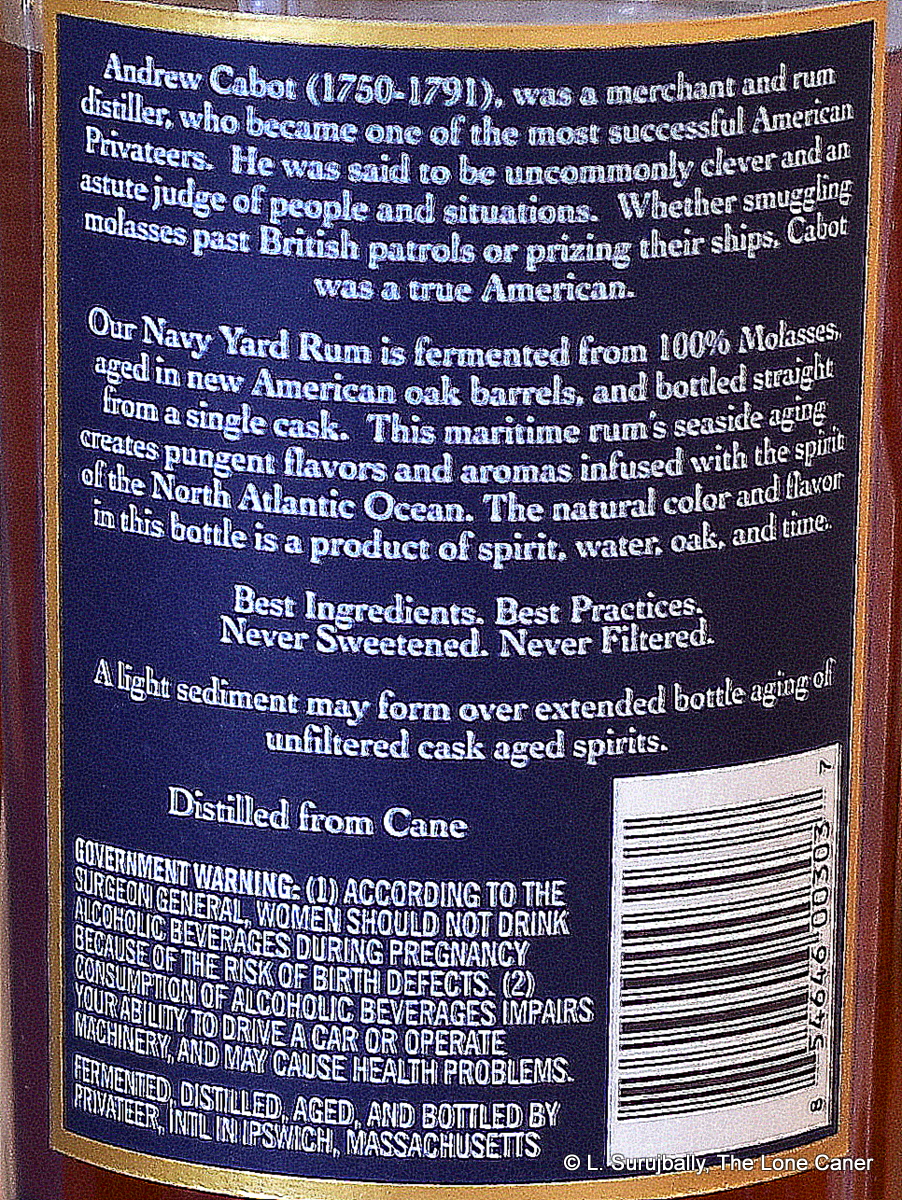

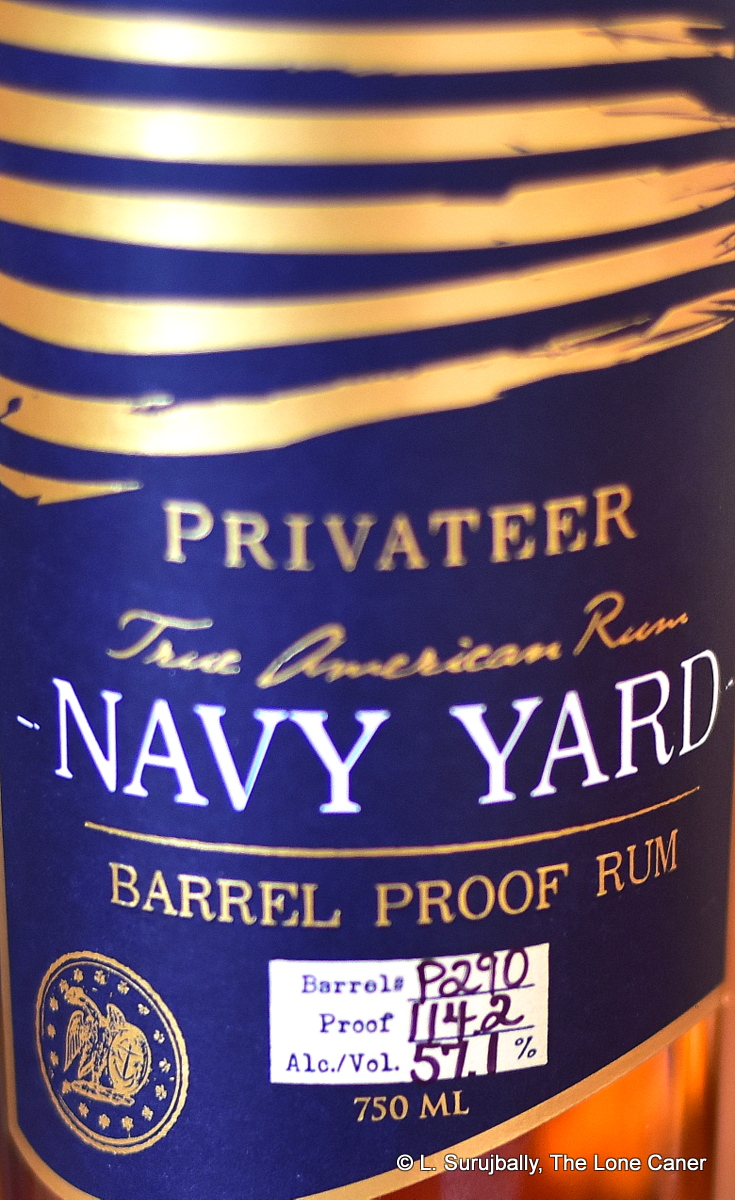

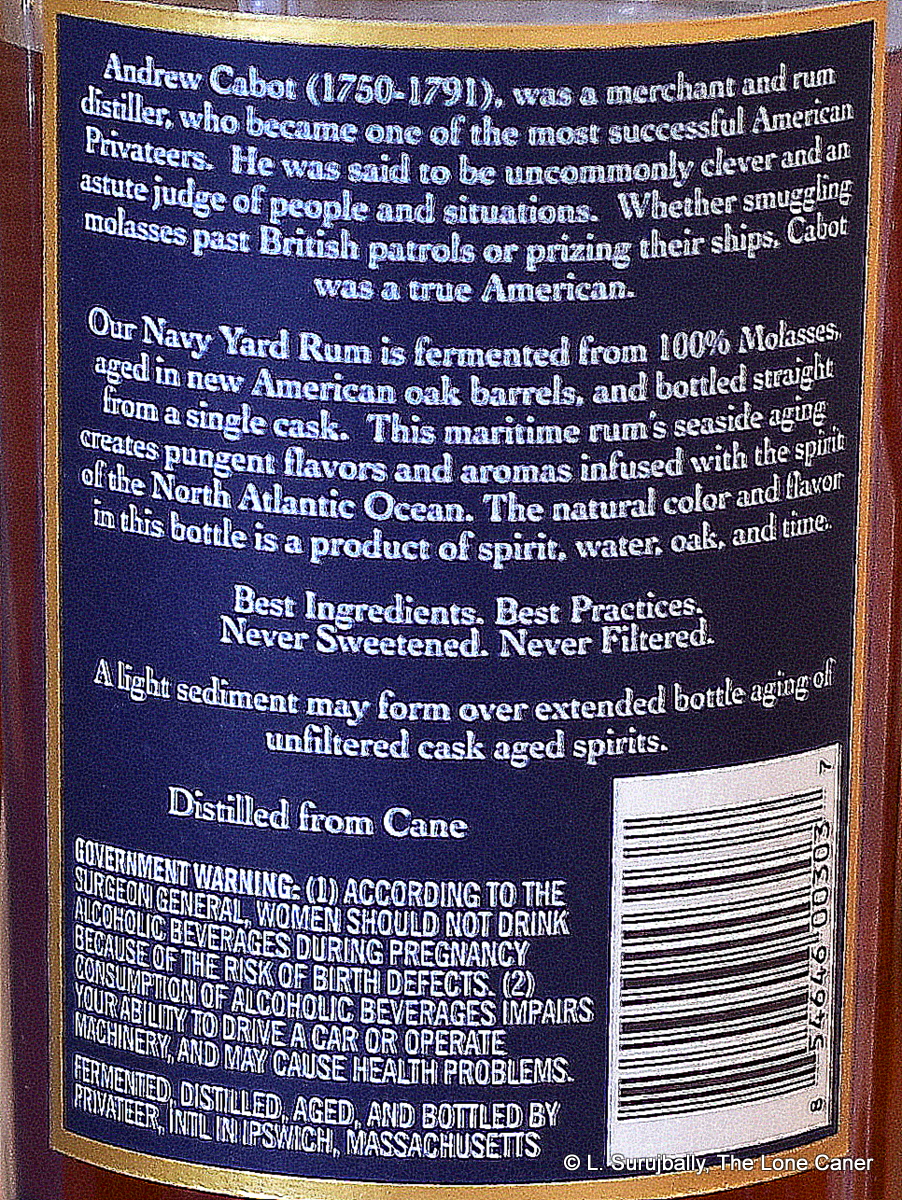

Privateer was formed by Andrew Cabot after he walked away from his tech-CEO day job in 2008 and decided to try his hand at making a really good American rum, something many considered to be a contradiction in terms (some still do). In 2011 he opened a distillery in an industrial park in Ipswich, Massachusetts but dissatisfied with initial results sniffed around for a master distiller who could deliver on his vision, and picked a then-unemployed Ms. Cambell who had distilling experience with whiskey and brandy (and cognac), and she has stayed with the company ever since. The rum is made from grade A molasses, and is twice distilled, once in a pot and once in a columnar still, before being laid to rest in charred american oak barrels for a minimum of two years. The company’s ethos is one of no additives and no messing around, which I’m perfectly happy to take on trust.

Privateer was formed by Andrew Cabot after he walked away from his tech-CEO day job in 2008 and decided to try his hand at making a really good American rum, something many considered to be a contradiction in terms (some still do). In 2011 he opened a distillery in an industrial park in Ipswich, Massachusetts but dissatisfied with initial results sniffed around for a master distiller who could deliver on his vision, and picked a then-unemployed Ms. Cambell who had distilling experience with whiskey and brandy (and cognac), and she has stayed with the company ever since. The rum is made from grade A molasses, and is twice distilled, once in a pot and once in a columnar still, before being laid to rest in charred american oak barrels for a minimum of two years. The company’s ethos is one of no additives and no messing around, which I’m perfectly happy to take on trust.

So, all that done away with, what’s this Navy Yard rum, which was first introduced back in 2016, actually like?

Well, not bad at all. Each of the three times I tried the rum, the first thing out the door was sawdust and faint pencil shavings, swiftly dissipating to be replaced by vanilla, crushed walnuts and almonds, salted butter, caramel, butterscotch, a touch of the molasses brush, and the faintest tinge of orange peel. What is surprising about this admittedly standard and straightforward – even simplistic – profile is how well it comes together in spite of the lack of clearly evident spices, fruits and high notes that would balance it off better. I mean, it works – on its own level, true, dancing to its own beat, yes, a little off-kilter and nothing over-the-top complex, sure…but it works. It’s a solid, aromatic dram to sniff.

The mouthfeel is quite good, one hardly feels the burn of navy strength 57.1%…at least not initially. When sipped, at first it feels warm and oily, redolent of aromatic tobacco, tart sour cream on a fruit salad (aha! – there they were!) composed of blueberries, raspberries and unripe peaches. Vanilla remains omnipresent and unavoidable, but it does recede somewhat and tries hard not to be obnoxious – a more powerful presence might derail this rum for good. As it develops the spiciness ratchets up without ever going overboard (although it does feel a bit thinner than the nose and the ABV had suggested it would be), and gradually dates and brine and olives and figs make themselves known. The rather dry finish comes gradually and takes its time without providing anything new, summing up the whole experience decently – with salted caramel, vanilla, butter, cereal, anise and a hint of fruits — and for me, it was a diminution of the positive experience of the nose and taste.

Overall, it’s a good young rum which shows its blended philosophy and charred barrel origins clearly. This is both a strength and a weakness. A strength in that it’s well blended, the edges of pot and column merging seamlessly; it’s tasty and strong, with just a few flavours coming together. What it lacked was the complexity and depth a few more years of ageing might have imparted, and a series of crisper, fruitier notes that might balance it off better; and as I’ve said, the char provided a surfeit of vanilla, which was always too much in the front to appeal to me.

Overall, it’s a good young rum which shows its blended philosophy and charred barrel origins clearly. This is both a strength and a weakness. A strength in that it’s well blended, the edges of pot and column merging seamlessly; it’s tasty and strong, with just a few flavours coming together. What it lacked was the complexity and depth a few more years of ageing might have imparted, and a series of crisper, fruitier notes that might balance it off better; and as I’ve said, the char provided a surfeit of vanilla, which was always too much in the front to appeal to me.

I’ve often remarked about American spirits producers who make rum, that rum seems to be something of a sideline to them, a cheaply-made cash filler to make ends meet while the whiskies that are their true priorities are ageing. That’s not the case here because the company has been resolutely rum-focused from eight o’clock, Day One – but when I tasted it, I was surprised to be reminded of the Balcones rum from Texas, with which it shared quite a lot of textural and aromatic similarities, and to some extent also the blended pot/column Barbadian rums with which Foursquare has had such success (more Doorly’s than ECS, for the curious). That speaks well for the rum and its brothers up and down the line, and it’s clear that there’s nothing half-pint or half-assed about the Navy Yard or Privateer at all. For me, this rum is not at the top of the heap when rated globally, but it is one of the better ones I’ve had from the US specifically. What it achieves is to make me want to try others from the company, pronto, and if that isn’t the sure sign of success by a master distiller, then I don’t know what is.

(#658)(83/100)

Opinion

After I wrote the above, I wondered about the discrepancy in my own perception of the Navy Yard, versus the really positive commentaries I’d read, both on social media and the few reviews others had written (94 points on Distiller, for example, and Drink Insider rated it 92 with nary a negative note anywhere on FB). Now, there is as yet no reviewer or commentator outside the US who has written about the Navy Yard (or others in the line), partly because its distribution remains there; those who did really went ape for the thing, some going so far as to call it the best american rum, so why didn’t I like it more?

The only answer I can come up with that isn’t directly related to my own palate and experience tasting rums from around the world, is that they are not coming to Privateer with the same background as others are, or I do. The sad Sahara of what is euphemistically called “rum choice” in the US, a resultant of the three-tier distribution dysfunction they amusingly call a “system”, promotes a rum selection of cheap quantity, but so denuded of real quality that when the girl next door makes something so much better than the mass-produced crap that masquerades as top-drawer rum over there, it just overloads the circuits of the local tippling class, and the points roll in like chips at a winning table in Vegas.

This is not in any way to take away from the achievement of Maggie Cambpbell and others like her, who work tirelessly every day to raise the low bar of American rumdom. Reading around and paying attention makes it clear that Ms. Campbell is a knowledgeable and educated rum junkie, making rum to her own specs, and releasing juice that’s a step above many other US brands. The next step is to make it even better so that it takes on better known Names from around the world which – for now – rate higher. Given her fierce commitment to the brand and the various iterations they’re putting out the door, I have no doubt there will be much more to come from Privateer and I look forward to the day when the company’s hooch muscles its way to the forefront of the global rum scene, and not just America’s.

Other Notes

I drew on Matt Pietrek’s deep dive for some of the biographical details, as well as articles on Thrillist, Imbibe and various posts about Privateer on FB. Details of the company, Ms. Campbell and the distillation steps can be found both Matt’s work and t8ke’s review, here. This is one of those cases where there’s so much information washing around that a synopsis is all that’s needed here, and if your interest has been piqued, follow the links to go deeper.

If we accept these data points, then of course the Casino is not, by all current definitions, a rum, and in point of fact, the entry might just as easily be listed in the Rumaniacs page since this version is no longer being made — the word “rum” was either replaced by “room” or dropped completely from the label when Hungary joined the EU in 2004, and that suggests a manufacture for the product I tasted of around 1988-2003 which actually makes it a heritage rum entry, but what the hell.

If we accept these data points, then of course the Casino is not, by all current definitions, a rum, and in point of fact, the entry might just as easily be listed in the Rumaniacs page since this version is no longer being made — the word “rum” was either replaced by “room” or dropped completely from the label when Hungary joined the EU in 2004, and that suggests a manufacture for the product I tasted of around 1988-2003 which actually makes it a heritage rum entry, but what the hell.

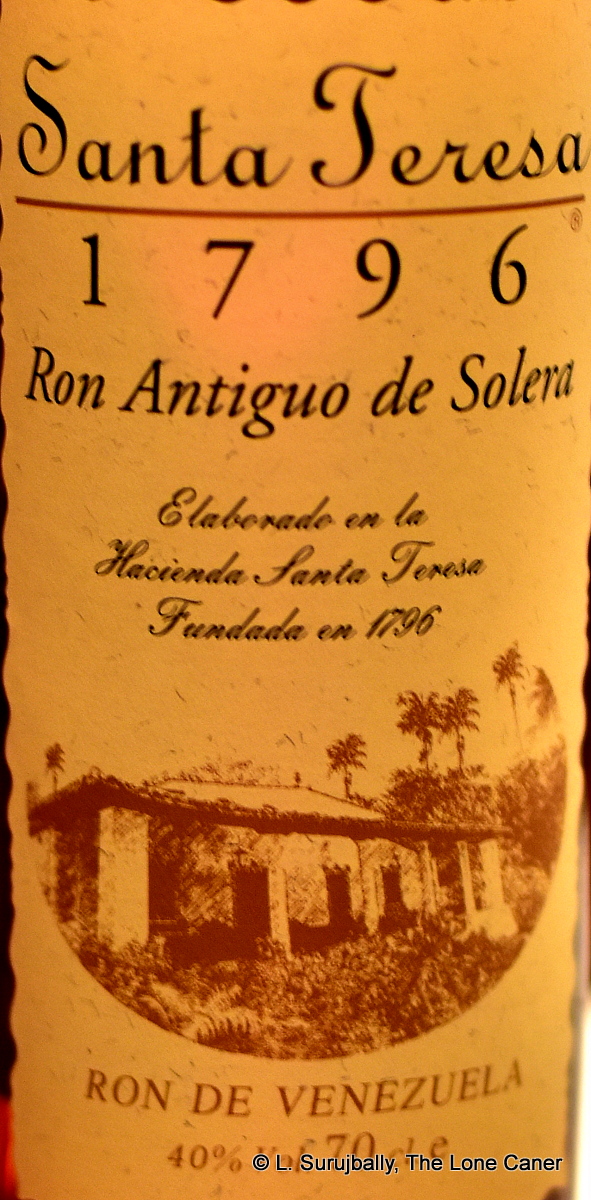

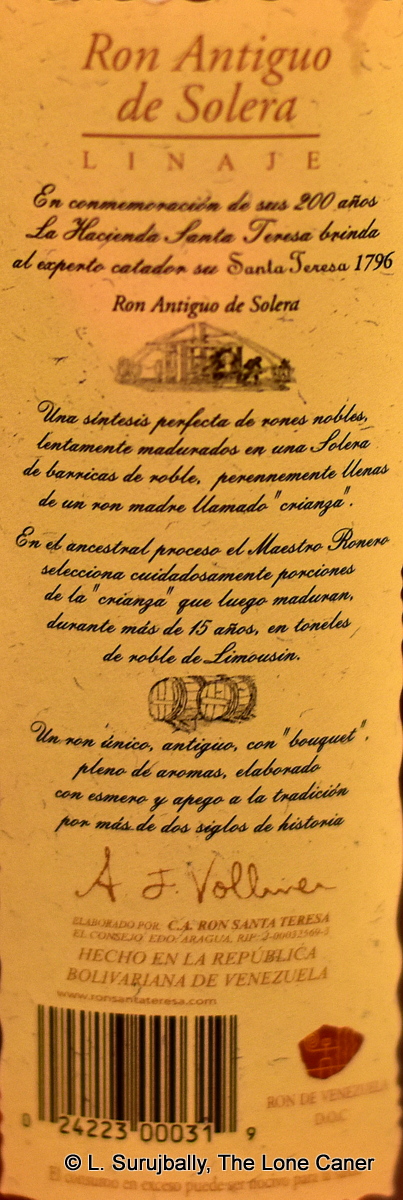

It’s inoffensive in the extreme, there’s little to dislike here (except perhaps the strength), and for your average drinker, much to admire. The palate is quite good, if occasionally vague – light white fruits and toblerone, nougat, salted caramel ice cream, bon bons, sugar water, molasses, vanilla, dark chocolate, brown sugar and delicate spices – cinnamon and nutmeg. It’s darker in texture and thicker in taste than I recalled, but that’s all good, I think. It fails on the finish for the obvious reason, and the closing flavours that can be discerned are fleeting, short, wispy and vanish too quick.

It’s inoffensive in the extreme, there’s little to dislike here (except perhaps the strength), and for your average drinker, much to admire. The palate is quite good, if occasionally vague – light white fruits and toblerone, nougat, salted caramel ice cream, bon bons, sugar water, molasses, vanilla, dark chocolate, brown sugar and delicate spices – cinnamon and nutmeg. It’s darker in texture and thicker in taste than I recalled, but that’s all good, I think. It fails on the finish for the obvious reason, and the closing flavours that can be discerned are fleeting, short, wispy and vanish too quick.

The rum was standard strength (40%), so it came as little surprise that the palate was very light, verging on airy – one burp and it was gone forever. Faintly sweet, smooth, warm, vaguely fruity, and again those minerally metallic notes could be sensed, reminding me of an empty tin can that once held peaches in syrup and had been left to dry. Further notes of vanilla, a single cherry and that was that, closing up shop with a finish that breathed once and died on the floor. No, really, that was it.

The rum was standard strength (40%), so it came as little surprise that the palate was very light, verging on airy – one burp and it was gone forever. Faintly sweet, smooth, warm, vaguely fruity, and again those minerally metallic notes could be sensed, reminding me of an empty tin can that once held peaches in syrup and had been left to dry. Further notes of vanilla, a single cherry and that was that, closing up shop with a finish that breathed once and died on the floor. No, really, that was it.

Next word: “Black”. Baby Rum Jesus help us. Long discredited as a way to classify rum, and if you are curious as to why, I refer you to

Next word: “Black”. Baby Rum Jesus help us. Long discredited as a way to classify rum, and if you are curious as to why, I refer you to

The “Guyana” spelling sets a lower post-independence date of 1966. Grants also released a Navy Rum and a Demerara Rum – both from Guyana, and both at “70º proof”. The address is written differently on their labels though, being “Grants of Saint James” on the Demerara label (Bury Lane is in the area of St. James, and a stone’s throw away from St. James’s Street…and BBR). Grants was still referring to itself as “of St. James” first (and until 1976 at least), but I think it’s the 40% ABV that’s key here, since that only came into effect in the mid 1980s in the UK.

The “Guyana” spelling sets a lower post-independence date of 1966. Grants also released a Navy Rum and a Demerara Rum – both from Guyana, and both at “70º proof”. The address is written differently on their labels though, being “Grants of Saint James” on the Demerara label (Bury Lane is in the area of St. James, and a stone’s throw away from St. James’s Street…and BBR). Grants was still referring to itself as “of St. James” first (and until 1976 at least), but I think it’s the 40% ABV that’s key here, since that only came into effect in the mid 1980s in the UK.

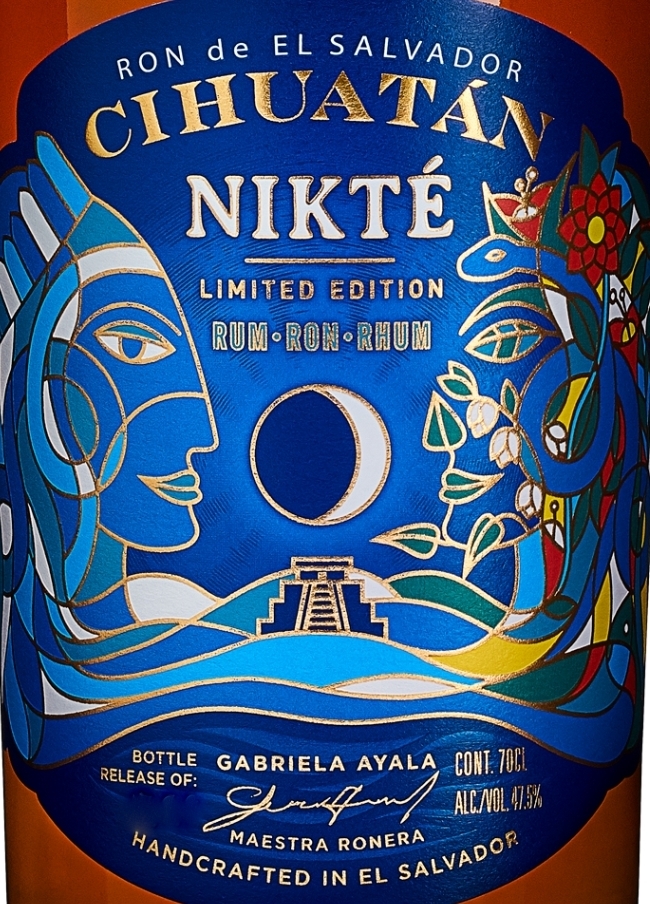

The name of the rum (or ron, if you will) relates back to the Mayan motif that has been part of the brand from the inception:

The name of the rum (or ron, if you will) relates back to the Mayan motif that has been part of the brand from the inception:

The Strand 101° was specifically designed by Knud Strand, a colourful Danish distributor who worked closely with Robert Greaves (as he had with many brands before) to bring the Mhoba line to market. What he was looking for was to create a blend of unaged and aged rum from pot stills, adhering to something of the S&C profile but from only one still (not two or more). He was messing around with samples some time back and after making his selections finally came back to two, both fullproof — one, slightly aged was too woody, with the other unaged one perhaps too funky.

The Strand 101° was specifically designed by Knud Strand, a colourful Danish distributor who worked closely with Robert Greaves (as he had with many brands before) to bring the Mhoba line to market. What he was looking for was to create a blend of unaged and aged rum from pot stills, adhering to something of the S&C profile but from only one still (not two or more). He was messing around with samples some time back and after making his selections finally came back to two, both fullproof — one, slightly aged was too woody, with the other unaged one perhaps too funky.

This is a rum that has become a grail for many: it just does not seem to be easily available, the price keeps going up (it’s listed around €300 in some online shops and I’ve seen it auctioned for twice that amount), and of course (drum roll, please) it’s released by Richard Seale. Put this all together and you can see why it is pursued with such slack-jawed drooling relentlessness by all those who worship at the shrine of Foursquare and know all the releases by their date of birth and first names.

This is a rum that has become a grail for many: it just does not seem to be easily available, the price keeps going up (it’s listed around €300 in some online shops and I’ve seen it auctioned for twice that amount), and of course (drum roll, please) it’s released by Richard Seale. Put this all together and you can see why it is pursued with such slack-jawed drooling relentlessness by all those who worship at the shrine of Foursquare and know all the releases by their date of birth and first names.

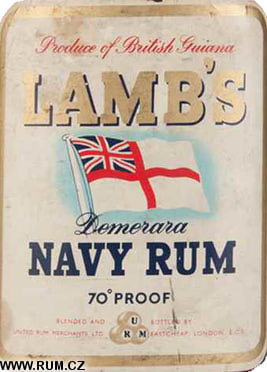

This bottle likely comes from the late 1970s: there is an earlier version noted as being from “British Guiana” that must have dated from the 1960s (Guyana gained independence in 1966) and by 1980 the UK largely ceased using degrees proof as a unit of alcoholic measure; and United Rum Merchants was taken over in 1984, which sets an absolute upper limit on its provenance (the URM is represented by the three barrels signifying Portal Dingwall & Norris, Whyte-Keeling and Alfred Lamb who merged in 1948 to form the company). Note also the “Product of Guyana” – the original blend of 18 different rums from Barbados, Guyana, Jamaica and Trinidad pioneered by Alfred Lamb, seems to have been reduced to Guyana only for the purpose of releasing this one.

This bottle likely comes from the late 1970s: there is an earlier version noted as being from “British Guiana” that must have dated from the 1960s (Guyana gained independence in 1966) and by 1980 the UK largely ceased using degrees proof as a unit of alcoholic measure; and United Rum Merchants was taken over in 1984, which sets an absolute upper limit on its provenance (the URM is represented by the three barrels signifying Portal Dingwall & Norris, Whyte-Keeling and Alfred Lamb who merged in 1948 to form the company). Note also the “Product of Guyana” – the original blend of 18 different rums from Barbados, Guyana, Jamaica and Trinidad pioneered by Alfred Lamb, seems to have been reduced to Guyana only for the purpose of releasing this one.

Privateer

Privateer Overall, it’s a good young rum which shows its blended philosophy and charred barrel origins clearly. This is both a strength and a weakness. A strength in that it’s well blended, the edges of pot and column merging seamlessly; it’s tasty and strong, with just a few flavours coming together

Overall, it’s a good young rum which shows its blended philosophy and charred barrel origins clearly. This is both a strength and a weakness. A strength in that it’s well blended, the edges of pot and column merging seamlessly; it’s tasty and strong, with just a few flavours coming together

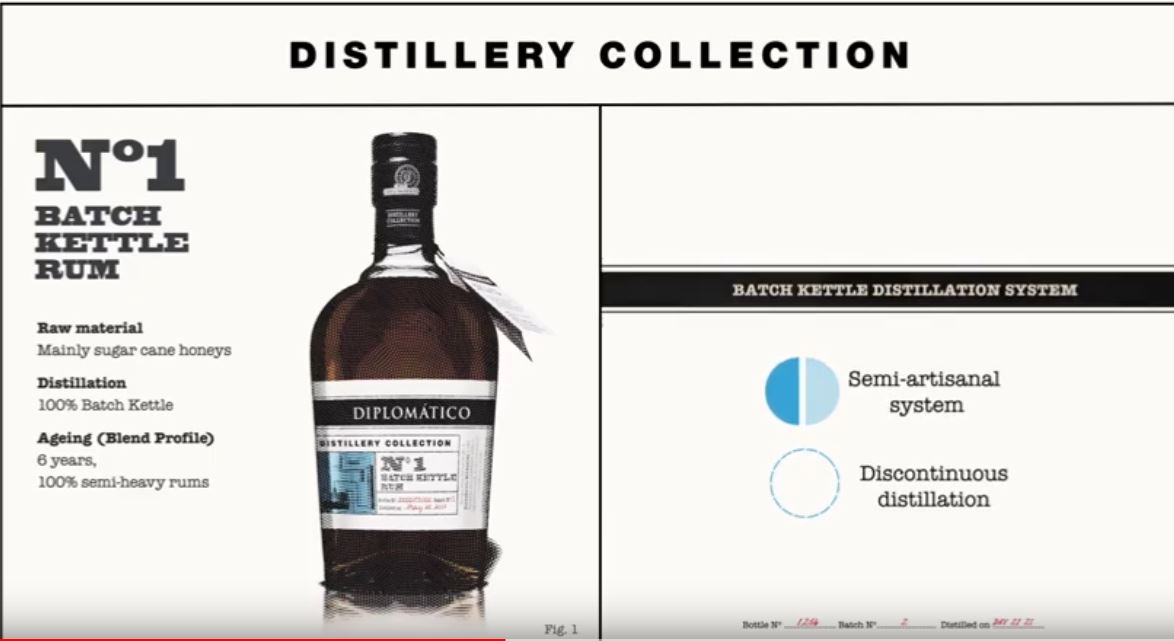

Things took an interesting turn around 2017 when No.1 and No.2 versions of the “Distillery Collection” were trotted out with much fanfare. The purpose of the Collection was to showcase other stills they had – a “kettle” (sort of a boosted pot still, for release No.1), a Barbet continuous still (release No.2) and an undefined pot still (release No.3, released in April 2019). These stills, all of which were acquired the year the original company was founded, in 1959, were and are used to provide the distillates which are blended into their various commercial marques, and until recently, such blends were all we got. One imagines that they took note of DDL’s killer app and the rush by Jamaica and St Lucia to work with the concept and decided to go beyond their blended range into something more specific.

Things took an interesting turn around 2017 when No.1 and No.2 versions of the “Distillery Collection” were trotted out with much fanfare. The purpose of the Collection was to showcase other stills they had – a “kettle” (sort of a boosted pot still, for release No.1), a Barbet continuous still (release No.2) and an undefined pot still (release No.3, released in April 2019). These stills, all of which were acquired the year the original company was founded, in 1959, were and are used to provide the distillates which are blended into their various commercial marques, and until recently, such blends were all we got. One imagines that they took note of DDL’s killer app and the rush by Jamaica and St Lucia to work with the concept and decided to go beyond their blended range into something more specific.

First off, it’s a 40% rum, white, and filtered, so the real question is what’s the source? The back label remarks that it’s made from “first pressing of virgin Maui sugar cane” (as opposed to the slutty non-Catholic kind of cane, I’m guessing) but the

First off, it’s a 40% rum, white, and filtered, so the real question is what’s the source? The back label remarks that it’s made from “first pressing of virgin Maui sugar cane” (as opposed to the slutty non-Catholic kind of cane, I’m guessing) but the  With some exceptions, American distillers and their rums seem to operate along such lines of “less is more” — the exceptions are usually where owners are directly involved in their production processes, ultimate products and the brands. The more supermarket-level rums give less information and expect more sales, based on slick websites, well-known promoters, unverifiable-but-wonderful origin stories and enthusiastic endorsements. Too often such rums (even ones labelled “Super Premium” like this one) when looked at in depth, show nothing but a hollow shell and a sadly lacking depth of quality. I can’t entirely say that about the Beach Bar Rum – it does have some nice and light notes, does not taste added-to and is not unpleasant in any major way – but the lack of information behind how it is made, and its low-key profile, makes me want to use it only for exactly what it is made: not neat, and not to share with my rum chums — just as a relatively unexceptional daiquiri ingredient.

With some exceptions, American distillers and their rums seem to operate along such lines of “less is more” — the exceptions are usually where owners are directly involved in their production processes, ultimate products and the brands. The more supermarket-level rums give less information and expect more sales, based on slick websites, well-known promoters, unverifiable-but-wonderful origin stories and enthusiastic endorsements. Too often such rums (even ones labelled “Super Premium” like this one) when looked at in depth, show nothing but a hollow shell and a sadly lacking depth of quality. I can’t entirely say that about the Beach Bar Rum – it does have some nice and light notes, does not taste added-to and is not unpleasant in any major way – but the lack of information behind how it is made, and its low-key profile, makes me want to use it only for exactly what it is made: not neat, and not to share with my rum chums — just as a relatively unexceptional daiquiri ingredient.

With all due respect to the makers who expended effort and sweat to bring this to market, I gotta be honest and say the Blackwell Fine Jamaican Rum doesn’t impress. Part of that is the promo materials, which remark that it is “A traditional dark rum with the smooth and light body character of a gold rum.” Wait, what? Even Peter Holland usually the most easy going and sanguine of men, was forced to ask in

With all due respect to the makers who expended effort and sweat to bring this to market, I gotta be honest and say the Blackwell Fine Jamaican Rum doesn’t impress. Part of that is the promo materials, which remark that it is “A traditional dark rum with the smooth and light body character of a gold rum.” Wait, what? Even Peter Holland usually the most easy going and sanguine of men, was forced to ask in  With respect to the good stuff from around the island — and these days, there’s so much of it sloshing about — this one is feels like an afterthought, a personal pet project rather than a serious commercial endeavour, and I’m at something of a loss to say who it’s for. Fans of the quiet, light rums of twenty years ago? Tiki lovers? Barflies? Bartenders? Beginners now getting into the pantheon? Maybe it’s just for the maker — after all, it’s been around since 2012, yet how many of you can actually say you’ve heard of it, let alone tried a shot?

With respect to the good stuff from around the island — and these days, there’s so much of it sloshing about — this one is feels like an afterthought, a personal pet project rather than a serious commercial endeavour, and I’m at something of a loss to say who it’s for. Fans of the quiet, light rums of twenty years ago? Tiki lovers? Barflies? Bartenders? Beginners now getting into the pantheon? Maybe it’s just for the maker — after all, it’s been around since 2012, yet how many of you can actually say you’ve heard of it, let alone tried a shot?  We hear a lot about Damoiseau, HSE, La Favorite and Trois Rivieres on social media, while J.M. almost seems to fall into the second tier of famous names. Though not through any fault of its own – as far as I’m concerned they have every right to be included in the same breath as the others, and to many, it does.

We hear a lot about Damoiseau, HSE, La Favorite and Trois Rivieres on social media, while J.M. almost seems to fall into the second tier of famous names. Though not through any fault of its own – as far as I’m concerned they have every right to be included in the same breath as the others, and to many, it does.